Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Historia

On-line version ISSN 2309-8392

Print version ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.68 n.2 Durban Nov. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8392/2023/v68n2a2

ARTICLES

The Face of Battle: The 'Fighting First's' Baptism of Fire at the Battle of Elandslaagte, 21 October 1899

Dawid J. Mouton*

Temporary lecturer and final year doctoral student at the University of Pretoria. dvdmouton@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This article investigates the experiences of the 1st Battalion of the Manchester Regiment in the Battle of Elandslaagte fought on 21 October 1899 during the South African War of 1899 to 1902. This was the Manchesters' first battle in nearly two decades and their first against modern weapons. Studies of the experiences of ordinary British soldiers during the South African War are limited. This scrutiny of letters written by the officers and troops of the Manchesters is supplemented by accounts published in British newspapers and an unpublished letter preserved in the Manchester Regiment Archive, all of which have been used to enhance existing narratives of the battle by exploring the soldiers' perspectives of war. The article suggests that by making use of such sources it is possible to reconstruct the British 'face of battle' during the South African War. These published letters have some limitations, however, and are inclined to adhere to the popular 'Tommy Atkins' stereotype. Exploring the battle from the Manchesters' viewpoint reveals that even though Elandslaagte was a near perfect execution of the three-stage set-piece battle, the soldiers involved experienced a turmoil of emotions ranging from confusion, frustration, loss, pain, discomfort, and even joy.

Keywords: Battle of Elandslaagte; the face of battle; experience of battle/combat; New Military History; South African War/Anglo-Boer War; military correspondence in the press; British soldiers; 1st Manchester Regiment.

OPSOMMING

Die doelwit van hierdie artikel is om die ervaring van die 1ste Manchester Regiment tydens die Slag van Elandslaagte op 21 Oktober 1899, 'n veldslag tydens die Suid-Afrikaanse Oorlog van 1899 tot 1902, te ondersoek. Dit was die 1ste Manchesters se eerste geveg na amper 20 jaar en teen moderne wapens. Studies oor Britse soldate se ervarings tydens die Suid-Afrikaanse Oorlog is beperk. Die soldate se perspektief kan egter ondersoek word deur die studie van briewe wat geskryf is deur beide offisiere en gewone soldate. Heelwat briewe was in Britse koerante gepubliseer, terwyl een ongepubliseerde brief in die Manchester Regiment Argief bewaar word. Hierdie bronne bou op bestaande beskrywings van die Slag van Elandslaagte vanuit die perspektief van die soldate. Hierdie artikel se standpunt is dat dit moontlik is om die Britse ervaring van gevegte, die sogenaamde face of battle', te rekonstrueer danksy die briewe wat in die Britse media gepubliseer is. Hierdie briewe het egter hul perke, soos party soldate se pogings om hulself volgens die populare 'Tommy Atkins' stereotipe voor te stel. Die verkenning van hierdie slag vanuit die Manchesters' se perspektief onthul dat, ten spyte van die feit dat die slag 'n amper perfekte voorbeeld van die drie-fase stellingskryg was, die ervaring vir die soldate 'n mengelmoes van emosies was, soos verwarring, frustrasie, verlies, pyn, ongemak, en selfs vreugde.

Sleutelwoorde: Slag van Elandslaagte; die aangesig van die stryd; gevegservaring; Nuwe Militêre Geskiedenis; Suid-Afrikaanse Oorlog/Anglo-Boereoorlog; militêre korrespondensie in die pers; Britse soldate; 1ste Manchester Regiment.

Introduction

This article focuses on the experiences of the fighting men of the 1st Battalion, The Manchester Regiment - the so-called 'Fighting First'1 - in the Battle of Elandslaagte during the South African War of 1899-1902. The battle, fought on 21 October 1899, will serve as the lens through which to explore their experiences, and the military aspects will not be discussed in detail, unless they are relevant to the 1st Manchesters' experiences. One of the reasons why such an account is so valuable for military historians, is because the soldiers were rather inexperienced, or 'green'. This was a regular line infantry battalion and they were professional soldiers. Nevertheless, for most of them, this was their first introduction to combat. They faced modern weapons, which was a novelty for most British soldiers at this particular time.

There are several accounts of this battle, although most only touch briefly, if at all, on what was experienced, physically and emotionally, by the rank-and-file soldiers. Yet despite ample sources, British soldiers' experiences have had very little attention in the historiography of the South African War, despite it being Britain's largest and costliest colonial war.2 The 1st Manchesters is no exception, and hitherto no serious attempt focuses on their experiences during this particular battle.

First, this article will situate the 'face of battle' subgenre in the historiography of New Military History. Its place in the historiography of the South African War is then explored with regard to the experiences of British soldiers, and the Manchesters in particular. Thereafter, a brief history of the 1st Manchesters is given, showing that in the South African War, this battalion was relatively inexperienced in combat.

The sources used to reconstruct the 1st Manchesters' experience of the 'face of battle' are then examined. An important source comprises letters published in British newspapers at the time. They are significant because they convey a wealth of information on the perspectives of soldiers from all ranks and these experiences are largely uncensored. The discussion comprises three sections: the first looks at what the men experienced prior to the battle and includes a brief discussion of their training. The second covers the battle proper, which commenced late in the afternoon. The final section concerns itself with what the men experienced and looks at their thoughts after the last shot was fired.

Approaching the Battle of Elandslaagte from the Manchesters' perspective allows a view of the battle from the more personal vantage point of those who took part in the fighting. Previous accounts have tended to focus on the operational aspects, such as military tactics and the strategic outcome. This article argues that reconstructing the face of battle from the viewpoint of British units during the South African War, is thus both feasible and illuminating because of the wealth of soldiers' correspondence published in the British press. However, inevitably these include a measure of self-censorship, bias and exaggeration. There are also some distortions and omissions in the correspondence. For the senior British officers and the historians, the Battle of Elandslaagte was one of the most successful three-stage set-piece battles of the war. From the vantage point of the soldiers, however, as we shall see, the experience was not always as 'neat' ... indeed it was more often confusing and suffused with a range of powerful emotions.

New Military History

The experiences of soldiers involved in a war comprise a subgenre of New Military History.3 Traditionally, military history tends to focus on what some call 'drum and trumpet' narratives of military campaigns and battles, focusing on topics such as strategy, tactics, logistics, and commanders.4 However, from about the middle of the twentieth century new avenues of research were being pursued, particularly by academic military historians.5 This signalled the development of 'new' military history which covers a range of fresh topics, particularly on the socio-cultural aspects of war. Among these are the experiences and perceptions of ordinary soldiers during battle. This approach is sometimes referred to as the 'face of battle', a term popularised by John Keegan's influential book The Face of Battle (1976).

The face of battle often forms a subset of a broader study focusing on the wide-ranging experiences of combatants during a war. Keegan was not the first to explore these aspects of warfare. In 1943, Bell Irvin Wiley published two volumes on the experiences and perceptions of soldiers in the American Civil War (1861-1865). Wiley claimed that the aim of his work is 'to present soldier life as it really was'. Matters he explored include aspects of the experience of Union and Confederate soldiers, such as their training, food, clothing, morale, perceptions of the enemy and various other aspects of warfare. Part of Wiley's attempt to present the soldiers' lives was to explore their perceptions and experiences in battle.6

More recently, studies that explore soldiers' experiences have appeared. Richard Holme's Firing Line, first published in 1985, provides an overview of the day-to-day lives of soldiers. Most are studies involving British troops and include modern and older wars. As for the two world wars, Denis Winter's Death's Men: Soldiers of the Great War (1988) and Paul Fussell's Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War (1989) are noteworthy.7 The face of battle is thus a specialised subset of the overall experience of combatants in war.

Scholarship about the South African War was also influenced by New Military History, and has its own share of works which focus on the overall experiences of combatants, including the face of battle.8 One of the most notable is Fransjohan Pretorius's Life on Commando (1999), which focuses on the experiences of the Boer combatants, and, much like Wiley's work on American Civil War combatants, explores Boer experiences ranging from their equipment, clothing, food, thoughts about the war, religion, leisure, discipline, the experience of battle, perceptions about death, and perceptions of the enemy, among other themes. 9

In comparison, research on the experiences of the British soldier appears to be relatively limited. Laband (2007), Miller (2007) and Spiers (2004) contend that the British soldiers' experiences in the South African War is still largely unexplored.10 This does not mean that nothing has been written on such aspects, but posits that it is relatively limited in scope and depth. A notable contribution is the chapter headed 'Tommy Atkins in South Africa', by William Nasson,11 that is featured in P. Warwick and S.B. Spies's The South African War. The Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902 (1980). This chapter certainly provides a sense of what it was like for British soldiers to be involved in warfare, but much like Tommy Atkins's 'often empty belly', it leaves one wanting a more detailed exploration.12

Edward M. Spiers has produced several influential works about the Victorian army.13 His chapters on the South African War give a tantalising glimpse of life on campaign, but this is not his focus. In 2007, Stephen M. Miller published an important work on the experiences of British soldiers during the South African War, specifically those of the volunteers.14 It includes a compelling discussion of how this group of combatants perceived combat, although very few of them were involved in what John Keegan would classify as a 'battle'. In fact, by the time the volunteers arrived in South Africa, pitched battles were becoming rare, and the war was transforming into a guerilla conflict.

On the Battle of Elandslaagte there are numerous secondary sources and sometimes these works provide glimpses of what the battle was like from the perspective of the soldier. For instance, Thomas Pakenham's enduringly influential The Boer War (1979) provides a description of the battle and includes several direct quotations, giving the perspective of the men in the firing line. J.H. Breytenbach's earlier study provides an even more detailed description of the battle, but with little concern for the experiences of the combatants involved.15 By way of comparison, among a much wider study of the war, Spiers devotes two paragraphs to Elandslaagte and these provide a brief idea of what the 1st Devonshires and 2nd Gordon Highlanders experienced, specifically their thoughts about facing modern weaponry.16 With regard to the role of the 1st Manchesters in the battle, the most detailed account appears in H.C. Wylly's History of the Manchester Regiment (1925), but has only limited detail on the soldiers' experiences.17

A brief history of the 1st Manchesters up to 21 October 1899

The 1st Battalion of the Manchester Regiment began life as the 63rd Regiment of Foot in 1758. It was involved in several wars, most notably the Napoleonic Wars (18031815) and the Crimean War (1853-1856). In 1881, during the Childers Army Reform, it merged with the 96th Regiment of Foot, to become the 1st and 2nd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment respectively.

Before the South African War began in 1899, the last time the 1st Manchesters were actively involved in combat was the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-1880). During The Anglo-Egyptian War (1882), the Manchesters guarded Ismaila - an island in Lake Timsah (part of what became the Suez Canal) - for a few months, but they did not participate in any of the major engagements. After seeing service in Egypt, they spent the next 15 years in the United Kingdom. In 1897 they garrisoned Gibraltar, but on 23 August 1899 they were despatched as reinforcements to South Africa, reaching Natal on 20 September. When the South African War broke out on 11 October, ten days later the Manchesters fought their first 'modern battle' at Elandslaagte, nearly 20 years after their last combat experience. Thus, only a handful of the older men would have experienced combat previously, and certainly not any of those would have been in their twenties or thirties.

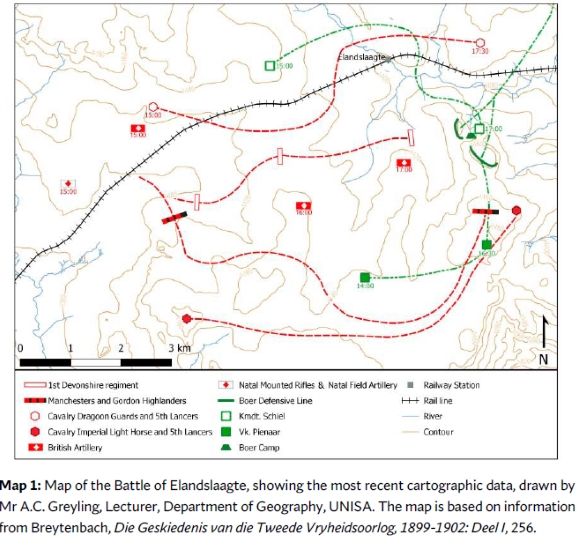

The Battle of Elandslaagte: An overview of the conflict and its significance

Before looking at the Manchesters' experiences, it is necessary to provide a brief overview of the Battle of Elandslaagte, although lack of space prevents a detailed description. On Saturday 21 October 1899, 341 men of the 1st Manchesters took part in a battle near the railway station of Elandslaagte in Natal, which was astride the main line of communication between Ladysmith and Dundee. Lieutenant-General George White could not allow the Boers to cut communications with the garrison at Dundee, and he sent out Major-General John French and a small force to restore the link. The battle was fought between a severely outnumbered Boer force of approximately 1 000 men occupying two linked hills overlooking the town and the train station, under the command of General Jan Kock, and a British force of almost 3 500 commanded by French.18 A unique feature of this battle was the cavalry charge against the routed Boers, a rare event during the South African War, although the Manchesters did not witness it. The outcome was a clear British victory, but the number of casualties is uncertain, and the sources vary in the number of casualties suffered. On the Boer side, a conservative estimate is 38 killed, 113 wounded, and 185 captured, almost 33 per cent of their force. On the British side, estimates are that 50 were killed and 213 wounded, only seven per cent of the total British force.19

The Battle of Elandslaagte was significant in several ways, for both the British Army in South Africa, and the 1st Manchesters in particular. It was one of the few battles in which the British doctrine of the three-phase set-piece battle played out almost flawlessly, at least from the perspective of the commanders and historians. The battle began with an artillery bombardment to 'soften up' the enemy and silence its artillery, laying the foundation for the second phase, the infantry assault. Once the Boers had been driven from their position by the infantry, the cavalry was unleashed as part of the third and final phase. They were positioned on the flanks to cut off the enemy's retreat, which turned the Boer withdrawal into a rout and ensured a decisive victory, although darkness descended soon after the infantry assault. The darkness prevented the cavalry from causing even more damage to the fleeing Boers. The Manchesters were part of the second phase infantry assault. Prior to Elandslaagte they were a relatively inexperienced unit but thereafter gained the reputation and self-identity as the 'Fighting First'. Captain Paton wrote: 'I don't fancy we shall have a finer fight ... it was a splendid bit of manoeuvring and most gallantly carried out. The men behaved magnificently, and the staff are full of the very highest praises of our regiment.'20 It was one of the few positive battle outcomes for the British during this early stage of the war, which soon afterwards was marred by several British defeats, particularly the disastrous battles of Stormberg, Magersfontein, and Colenso on 10, 11, and 15 December 1899 respectively.

In addition to ending in victory, the battle provided the first indication that the war would not be as easy as the British public, and politicians were speculating. Writing to his mother on 12 August 1899, Private Mayer said that the war would be 'a soft affair, and we shall get a medal for almost nothing, as the infantry will not very likely be required to fight'.21 His underestimation of the tenacity and skill of the enemy, or possibly his attempt at putting his mother's worries at ease, proved to be grim irony, because he was killed in the Manchesters' assault at Elandslaagte. Moreover, the victory at Elandslaagte did not prevent the Boer encirclement of Ladysmith by 2 November 1899, trapping the 1st Manchesters and other British units in a protracted siege until 28 February 1900.

Reconstructing the face of battle

The article draws on 16 letters written by 15 soldiers who fought in the Battle of Elandslaagte. Most of these letters were published in British newspapers. In addition, one unpublished letter was consulted and a number of other documentary sources were used.22 To reconstruct the experiences of the Manchesters in the Battle of Elandslaagte the most important and colourful source is the largely uncensored 'letters from the front' published in British newspapers.23 Most of the letters were written by the rank-and-file soldiers, but there were also a few from officers. It appears that the letters were not censored, which makes them even more valuable to historians. In The Queen's Regulations and Orders for the Army of 1899, it is stated that officers were obliged to endorse a private's letter by signing the envelope, but there was no specific instruction on whether this endorsement required the officer to read and/or censor the letter.24 E.M. Spiers, who is undoubtedly the leading expert on this topic, could find little to no indication of large-scale, systematic censorship of soldiers' letters.25 It was not unusual for these colourful letters to be sent by recipients (or even the writers) to be published in local and national newspapers.

There were several reasons why people sent soldiers' letters to the press. Most of the letters were passed on by family or friends to the local media. It is uncertain whether they were instructed to do so by the writers, or whether the recipients forwarded the letters on their own initiative to share news about family members to the wider community. More rarely, a soldier sent a letter directly to the editor of a newspaper to 'set the record straight'. A certain Private Evans was apparently so annoyed by the media's lack of attention regarding the Manchesters, that he wrote directly to the editor of the Manchester Evening News, explaining:

...you would greatly oblige me by placing in your paper a short report of the Battle of Elands Laagte [sic] ... I think it is only doing justice to the Lancashire people to let them know [that] their county regiment is doing its share ... I have seen in the papers other regiments praised and ours [was] left out.26

There were even competitions to encourage the public to send in letters from their loved ones. Such was the case when the Evening News awarded £1 to Mrs F.G. Miller for sharing the 'best letter from a soldier'.27 Small local newspapers benefited enormously from these letters, because they had limited budgets and could not afford a war correspondent. They were therefore keen to publish such letters in full, or as excerpts, or even just as summaries, because doing so enabled them to benefit from the public's interest in news of the war and how the soldiers were faring.

Such letters provided crucial details regarding the mindset of British soldiers, how they perceived their experience and also gave a view into life on campaign.28Despite the usual limitations of primary historical sources, such as factual inaccuracies and bias, these letters covered various topics such as their journey by ship, the food they ate, the privations they suffered, their leisure activities and the songs they sang. They also provided a window into their opinions of the war, perceptions of the enemy and how they experienced combat. It is thus, as Spiers has noted, surprising that only a few historians have made use of these published letters.29

These letters provide 16 accounts of varying levels of detail and quality, describing the events, experiences, and thoughts of the 1st Manchesters who fought in the Battle of Elandslaagte. They also reveal limited detail on the writers and their motives. Below, I focus on the three letters written by officers. It is worth noting that the officers at Elandslaagte fought in the front lines too, sharing the danger their men faced, and as will be shown, they paid a heavy price. Their perceptions of combat provide a valuable point of comparison to the perspectives expressed by the rank-and-file soldiers. Also of note is that the officers' letters were anonymous. This was common practice, because the officers were hesitant to expose their identity. Spiers explains that they were worried that their public letters might damage their professional reputations.30

However, one of these officers can be identified because he wrote about exactly the same events in another letter, which is preserved in the Manchester Regiment Archive. The writer, who signs himself as 'an officer of the First Manchesters', was published in the Manchester Guardian. He was Captain Donald Paton, who wrote to his mother from a temporary hospital in the Wesleyan Chapel in Ladysmith on 24 October 1899. The other officers are difficult to identify with any certainty. The second officer was one of four unwounded lieutenants,31 whose relatives forwarded his letter to Pearson's Weekly. He wrote to them from Ladysmith, but the date is unstated. The third officer is even more difficult to identify, because his rank is not provided. The only details which give a clue to his identity are that he was another (or perhaps the same) unwounded officer mentioned above, and that he might have sent his letter, written from Ladysmith on 24 October 1899, directly to the editor of The Wrexham Advertiser.32

Several letters were written by non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and other special ranks. For example, Sergeant-Major Haddon wrote a letter to Sergeant-Major Walkley of the 2nd Manchesters. The letter is short and is probably an extract of a longer letter, in which he provided some detail about the wounded officers. Another missive, this one undated, was published in The Manchester Weekly Times on 24 November 1899. It was written by Corporal W. Kelly to his father and reads: just a few lines to let you know I am going on all right up to now ... I suppose you would be thinking I had got shot in our last engagement'.33 Like most soldiers, Kelly wrote to his family to let them know he was alright and told them of his experiences.

Drummer Charles Toomey wrote from Ladysmith on 25 October 1899. Most of this letter appeared in The Wrexham Advertiser on 25 November 1899. He claimed that he was one of the two drummers who had sounded the bayonet charge against the Boer position. Then there is another from Bandsman William Powell, written to his friend, Tom Vaguhan of Portland Place, on 25 October 1899. The entire letter is reproduced in The Ashton Reporter on 25 November 1899, and ends with the rather demoralised line: 'I have not had a change of clothing for three weeks.'34

The regular fighting men, known by the rank of 'Private', also shared their experience of the battle. One of these letters was published anonymously in the Reading Mercury, Oxford Gazette, Newbury Herald and Berks County Paper on 30 December 1899 and was the winner of the competition for the best letter from a soldier. It was submitted by a Mrs Miller who had two brothers, both in the Manchester Regiment, who fought at Elandslaagte. One brother was named Bob and served in C Company. The other, the letter writer, was not named, but he served in D Company and was married with children. He wrote plaintively: '...my only wish is to see them again'.35 Another letter, although not anonymous, did not provide a surname. It was written on 7 November 1899 from Wynberg Hospital in Cape Town to the parents of 'John Willie and Albert'. Albert appears to be the author, and his left hand was wounded. Then there was Private Stokes who wrote two letters to his parents in Thurmaston, Leicester. This is a good example of how a paper's editor selected the news he thought would interest its readers rather than publishing a letter in full. Stokes's first letter was summarised by the editor, probably because it dealt with the voyage to South Africa. The editor must have decided that the readers were far more interested in the battle itself, because only battle-related extracts were published.36

Private J.W. Evans, who was wounded at Elandslaagte, wrote two letters, both of which appeared in the Manchester Evening News. They were published six days apart, on 21 November and 27 November 1899. The first was to his father, who lived in Junction Street, Manchester and was written from the temporary hospital in Ladysmith on 23 October 1899. The editor only published a few brief extracts of this. However, the second letter was sent directly to the editor, and was published in full, although the date it was written and where the author was, are not stated. Evans was determined to provide an account of the battle that would give the Manchesters their 'fair share of the glory'. Another was written by Private Michael Wall of D Company, who wrote to a friend in Gorton on 26 October 1899. His letter was published in full in The Ashton Herald on 2 December 1899. Private M. Little, also of D Company, wrote on 25 October 1899 to his sister in Duncan Street, Ashton. This letter was published in the Ashton Reporter on 2 December 1899. The editor explained to the readers that Little had grown up in Ashton and was 21 years old. He had joined the militia at the age of 17 but decided to join the Manchester Regiment soon afterwards. Lastly, Private Hardicre wrote a short letter in pencil, undated, from Ladysmith to his father Joseph Hardicre, and although only a paragraph in length, he provided several emotional perspectives and experiences. It was subsequently published, on 24 November 1899, in The Manchester Weekly Times.

Although the letters published in newspapers make up the bulk of the sources of this article, the Manchester Regiment Archive also includes other relevant documents. Of particular value is a Record of Service of the 63rd and 1st Battalion Manchester Regiment, dated 1758-1910. This was the work of various officers who were obliged to keep a record of the battalion's activities and major events. Even though it was written by the officers, it includes glimpses of what the men experienced during the battle.37 Additionally, Major A.W. Marden and Captain (Adjudant) W.P.E. Newbigging published a Rough Diary of the Doings of the 1st Battn. Manchester Regt. during the South African War, 1899-1902 (1904). Much of their information is based on the Record of Service, interlaced with some of their own perspectives. Other types of preserved sources in the regiment's archive, although seemingly irrelevant at first glance, also proved useful in reconstructing the soldier's experience during the battle, such as a collection of training booklets. These training booklets are useful for illustrating what the men expected as opposed to the reality of combat. Among a collection of 49 individual letters, mostly from officers, only one letter written by Captain Donald Paton in November 1899 from the hospital at Wynberg, Cape Town, refers to Elandslaagte. If it was not for the letters published in newspapers, Paton's letter would be the only personal account of the Battle of Elandslaagte in the regiment's archive.

Letters often include only the information which the writer thinks his readers will find interesting. Indeed, in one such letter an anonymous lieutenant wrote to an unknown recipient, saying: 'it is no use trying to describe the battle; you will probably have seen all about it in the papers.'38 However, and arguably more important to military historians, he then describes aspects of the battle which resonate most strongly with him. Another soldier - named Albert - expressed similar sentiments, writing to his parents: 'I suppose you have seen in the papers about the Battle of Elandslaagte which I was in'.39 He then proceeded to focus on issues he thought were noteworthy, such as his wound and being witness to seeing his friends from Manchester being shot dead in the course of the battle. Similarly, Captain Paton wrote to a fellow officer:

I had meant to give you a description of the battle, but I don't think there is much good doing it now, for it is a very old story, and we have all talked so much about it that I am heartily sick of it.40

Despite this, Paton then describes his rage at being wounded, his uncomfortably wet and cold night, and his gratitude to one of his soldiers who found him lying wounded and had kept him warm - information that provides deeper insight into the traumatic experience of warfare.

The writers also practised self-censorship and did not include their thoughts and experiences about aspects of the battle that they believed would be inappropriate, or which would put them in a bad light, such as admitting to deliberately avoiding combat during the fighting. Others again, chose to exaggerate their own prowess.41 Furthermore, some writers tried to fit their experiences into the popular 'Tommy Atkins' stereotype, which involved an undertone of working-class patriotism, coupled with a sense of national identity.

The image of 'Tommy Atkins' was propagated through various media, such as the press, popular literature, and music hall. Tommy Atkins represented a variety of images and ideals, best explained by Steve Attridge as

a popular myth of the common soldier; although his protean energies sometimes hint at subversion, these are simply the rough edges of a character whose moral being and physical strength are finally the property of the crown when there is a crisis ... the components of the myth, Tommy's heroism and patriotic fervour, his sentimentality and simple Christian faith, were the product of an idealized vision.42

These surviving published and unpublished letters, imperfect as they are, are helpful in recapturing some aspects of the 'face of battle' at Elandslaagte from the 1stManchesters' perspective. This issue is explored and contextualised further below.

Pre-battle

The 1st Manchesters had previously seen combat almost two decades earlier, and thus their training was their only preparation, and an important reference of their expectation of war. Training the British infantry for a modern war involved many theoretical elements, since no army had yet fought a large-scale war with the new rapid-firing, smokeless, magazine rifles such as the Lee-Metford, the Mauser, and the new quick-firing artillery with more powerful explosive shells. In 1889, Adjutant-General Garnet Wolseley wrote the first edition of Infantry Drill, which was still used on the eve of the South African War, albeit with minor changes from edition to edition. It is notable that the training text is overly clinical in presentation and tone. More importantly, the training instructions make almost no effort to account for an active, adaptable enemy firing back. Instead, the training is mechanical, neat and repetitive, as if the men were on a flat parade ground.43

Infantry training involved several main aspects, some of them outdated and untested. In short, the infantry was expected to reach the battlefield in column or quarter-columns, which made them vulnerable if caught by artillery or concealed riflemen. Once in contact with the enemy, the main body of the attacking force was screened by covering infantry in extended order. This was followed by three lines of men, a firing line, a support line, and a reserve line, all in extended order. These 'lines' were an archaic leftover from older conflicts, but the extended order of the lines was an attempt to mitigate the impact of modern weapons. Despite the efficacy of independent firing brought about by modern rifles, volley-fire was still deemed superior by many British officers, because it was believed it directed and concentrated the volume of fire, preserved ammunition, and was considered an aid to discipline. In retrospect, volley fire would have decreased the weight of fire, instead of increasing it. Military training also encouraged the use of cover when advancing against an enemy with modern rifles, which was certainly the correct thing to do. As a final element, it was emphasised that attack was still 'morally superior' to defence, and encouraged the men to cheer, beat drums, sound bugles, or play pipes during the final assault. Bayonet training for close-quarter engagement also remained a part of this attacking mentality. Infantry training was clearly in a period of transition, and only partially appreciated the impact of the 1890s innovations in weaponry. However, in emphasising discipline, it instilled a measure of resilience to heavy casualties.44

For the 1st Manchesters', the day of battle began with much uncertainty. In the early hours of the morning of 21 October 1899, 341 Manchesters boarded a train at Ladysmith on the line to Dundee.45 The Manchesters comprised four companies - 'C', 'D', 'F', and 'G', which was roughly half the battalion's strength. They were led by Lieutenant-Colonel Curran, with Major Watson, Captains Melville, Marden, Paton, Adjudant Newbigging, Lieutenants Danks, Hardcastle, Deakin, Fisher and Hunt-Grubbe. The rank-and-file were told little. Private Stokes wrote that they received no information that morning.46 Corporal Kelly reported the same.47 Another soldier wrote: '...we were dished out with a bit of bread each', and then being bundled into trains. Kelly added: 'None of us knew where we were going'.48 This lack of information must have caused some of them a measure of anxiety, although they do not mention it in their letters.

The Manchesters experienced their first taste of artillery fire a few hours later. As they disembarked at the station of Elandslaagte, they witnessed the outgunned Natal Field Battery in action, which had to withdraw at approximately 8:15 am. The Manchesters would be the next target.49 According to the Manchesters' accounts, which reinforce Wylly's and the Record of Service narrative, the shelling was remarkably accurate. Yet, the Boer fire had little physical effect, and the officers of the 1st Battalion speculated that the shell fuses were probably defective, as most did not burst when hitting the surface.50

Even so, the shelling discomfited the officers and men and forced them to withdraw to a safe distance. A letter by Private Evans observed that 'the shells [were] getting a little too warm for us, [so] we had to retire a little down the line ... and take up a position behind boulders to await an attack'.51 Another soldier reported that 'after two hours' riding [on the train] shells began flying over our heads. One dropped only twenty yards [18,2 m] from me, but luckily it did not burst. Off we had to go behind hills for cover'.52 Despite the ineffectiveness of the bombardment, it did have an impact on the men's nerves, and this was reflected anew on numerous other engagements during the war, on both sides.53

It is common for soldiers to display a variety of emotions, thoughts, and behaviour before going into combat, especially if it is their very first engagement. The Manchesters did not dwell on this aspect in their letters, however, even though they had to wait several hours for reinforcements to arrive, and they certainly knew that a battle was going to take place. One can merely speculate what went through their minds and how they behaved before battle commenced.

In his published works, Pretorius explains that the Boers behaved in various ways before a battle. The Manchesters' behaviour and thoughts as they waited were probably comparable. Some Boers kept themselves purposefully busy with all manner of small tasks, ranging from cleaning their rifles to packing supplies into their saddlebags. We learn that some felt mild to intense fear and panic, with distinctly pale faces, or were feeling nauseous. Some even shivered uncontrollably. Some men walked around nervously, while others sat quietly and stared into the distance. Some lit up a pipe and smoked, others prayed, while some men comforted those who were looking extremely nervous. Some of the younger men put on a brave face and joked and laughed. The presence of a confident and charismatic officer often helped to calm the men before combat.54

After waiting several hours, sufficient reinforcements finally arrived by 15:00 and French ordered the Manchesters and the Gordons to march behind the cover of a ridge and then to attack the left flank of the enemy position from the south. Once they had crossed the ridge, the men were now in plain sight of the enemy position and were somewhat daunted by what appeared to be a strong defensive terrain. As later relayed by officers Marden and Newbigging, it appeared to be a formidable position with a stony hill, and the approach only had large rocks and ant-hills as cover for the attacking Manchesters.55 One of the Manchester lieutenants wrote:

...the ground we had to get over, in the face of the heavy fire ... was such as must be seen before any conception can be formed of the danger of attacking the Boers in their strongholds. One almost wonders how the men could get over the ground without breaking their legs among the rocks and boulders, besides the splinters flying from the rocks in all directions around you.56

It seems the apparent strength of the enemy added to the 'glory' of the Manchesters' actions. Bandsman Powell states proudly: 'the Boers were in a strong position, but we charged at them and drove them away'.57 Drummer Toomey, expressing equally brave sentiments, wrote: the Boers thought they would have a good time of it ... but our boys were not to be beat, and, thank God, we wiped something off Majuba that day'.58This sentiment sounds stereotypically 'Tommy Atkins'.

The battle

As the Manchesters crested the ridge line facing the Boers at approximately 16:30,59they came under long-range fire from well-concealed riflemen. The Record of Service mentions that the Boers were well-hidden amid the rocks and brush,60 and the smokeless cordite gunpowder made it almost impossible to make out their exact positions. Mauser fire from roughly 1 000 to 1 500 metres away (the exact range is uncertain) drove them down to the ground to seek cover on an exposed grassy slope. This lasted almost seventeen minutes, and four men were hit.61 Captain Melville later explained to a journalist that he and his men had been unable to see a single Boer, even when they had advanced to within a quarter of a mile (402 m) and while under heavy rifle fire.62 The Gordons and Devons, as related by Spiers, commented on how frustrating it was to be shot at, but never able to see the enemy. Moreover, they commented on the futility of volley-fire under these circumstances, because there was no obvious target to concentrate on.63

The Manchesters were subjected to their 'baptism of fire' for approximately seventeen minutes. As Private Wall wrote to his friend in Gorton:

We got the order to drop on the field, and then came the funniest sensation I ever had in my life, when I could see the bullets dropping round my head. We lay like that for 17 minutes, and dared not stir.64

For Private Little, it was much the same. He wrote that 'it makes a fellow feel funny when the bullets first start whistling round your head'.65 It appears that for some soldiers, the experience of getting shot at for the first time was difficult to comprehend. This emotion is echoed by combatants in conflicts of the twentieth century, and as explained by Richard Holmes, 'for many soldiers their first experience of coming under fire is one of surprise and disbelief'.66

As for Captain Paton, he chose to express his first time under fire on the battlefield as an unpleasant quarter of an hour lying in the open with no cover at all', and followed this up by stating that the Boers were:

... using us as targets from about 2 000 yards [1 828 m] off and they made pretty fair practice, for though they only got two men in the front line the bullets were kicking up the dirt all around us. I got a bullet through my helmet, one of my Tommies had the heel of his boot shot off, and another got a shot through his water bottle.67

For some, the experience was outright terrifying, and one man did not hesitate to say so. One of the officers admitted:

... the time I felt most inclined to run away was, oddly enough, when we were nearly a mile from them [the Boers] and were firing long-range volleys at each other. I am sure they are trying to pick-off the officers, as while I was lying by myself in the open the bullets pattered all around me, but when I went up to speak to one of my n.c.o.'s [sic] there did not seem half as many.68

In contrast, some men alleged that they joked and laughed during the battle, or claimed they enjoyed it. Private Evans wrote that 'we kept advancing, laughing and joking and facing their heavy fire'.69 Captain Paton asserted: 'I enjoyed the battle tremendously from the start to the time I got knocked out; and I am sure my men were not a bit funky either, but treated the whole thing as a huge joke'.70 His choice of words implies some guesswork on his part. Another officer declared that 'on the whole I enjoyed it ... I had an excellent view of everything, as my company supplied half the firing line'.71

These statements might simply be bravado since others did not mention any feeling of merriment. On the other hand, treating battle as a light-hearted affair is not unknown in modern conflict. Denis Winter found that some men during the First World War admitted that they advanced into battle 'with jokes and fits of laughter'.72Winter speculates that men coped with the stress of battle in different ways. Some assumed a feeling of detachment from events around them, while others coped by 'enjoying' the battle, or at least thought they did.73 Alternatively, some men might have actually relished the sensation of combat, as was the case for several twentieth-century soldiers in Joanna Bourke's An Intimate History of Killing.74 Miller describes the same phenomenon in his study of the Volunteers during the South African War.75However, apart from a few individuals such as Captain Paton, it is difficult to believe that most of the Manchesters truly 'enjoyed' the experience.

Whether they enjoyed combat or not, some men tried to convey the sounds and turmoil of battle. Their description of the sounds is a colourful addition to existing accounts. Private Evans described how 'the enemy's bullets came whizzing over our heads like hailstones'.76 Another man described the sensation as a '...tin whistle playing a tune about your ears'.77 Soldiers from subsequent twentieth century conflicts used similar evocative descriptions to describe the sound of bullets: like birds flapping their wings in one's face, or like the crack of a whip.78

As the battle progressed, the men claimed that they grew accustomed to enemy fire. Private Little asserted that coming under fire was a strange experience, 'but you soon get used to it'.79 One of the officers wrote that 'the bullets were simply raining on us like hail . but somehow one hardly notices them'.80 The experience of 'getting used to' enemy fire is also mentioned by combatants in other twentieth century conflicts. Once soldiers overcame their initial terror, they realised that their worst fears were unfounded and that battle was something that they could endure.81Even the Boers, having benefited from little or no military training, reported that once the shooting began and they were over the worst of their nerves, they tended to enter a highly focused state of concentration, some even admitting to a degree of excitement and almost forgetting the potential death whistling around their ears.82

A war correspondent, describing the advance of the Manchesters, evoked the image of Tommy Atkins, who under heavy fire marched in orderly fashion, eschewing cover. He placed the following words into their mouths: "What!? Hide from those yokels? Let them shoot!"83 However, as the Record of Service and other accounts attest, advancing towards the enemy was not just a matter of moving fearlessly forward at a steady pace in neatly maintained lines, disregarding cover. Instead, they advanced in short bursts over the rough ground, under covering fire from the lines to the rear and their sides, and often had to change direction when sections of the battalion realised that the terrain prohibited certain approaches.84 As they neared the main Boer position, the Manchesters became easier targets and were subjected to intense, accurate rifle fire. It took them about an hour from that initial 'baptism of fire' to cross the stretch of ground, approximately 1.6 km long, that separated them from the enemy. The men sought cover as they advanced, as recommended in their training. Drummer Toomey tells us: 'we got to the Boers' camp about 6 p.m., and for an hour [as we approached] we were under the hottest fire known for years'.85Progress was thus painfully slow, and the accounts of the battle become rather confusing at this point.

The only certainty is that the Manchesters continued to ascend the hill in short bursts, always under heavy fire, and the ascent became increasingly steep and rocky the closer they got to the summit. At some point during the advance,86 they had to traverse barbed wire, where they lost several men while the officers cut the their way through - an eerie foreshadowing of the First World War. However, this obstacle was overcome and they continued their advance. Soon the attackers were bunched together, making for an easy target and casualties increased sharply as a result.87

The officers in particular suffered heavily during the ascent, since they were leading from the front, as demanded by tradition and training.88 It certainly did not help that the officers wielded revolvers and swords, which made them dangerously tempting targets. Captain Melville, who was wounded during the battle, was asked by a journalist about the shooting prowess of the Boers. Melville answered: all I know is that they were good enough for me'.89

Some men writing about the battle did not admit to fear. There were potent reasons for them to keep silent, since this would have gone against the popular public image of the doughty, brave 'Tommy Atkins'90 as well as a concern of being judged by comrades, family and friends. Paton expresses the opinion that it was 'all tommy-rot about fellows all being frightened the first time under fire'.91 With views such as this, especially from an officer, it was likely that some Manchesters would never admit to any fear or wavering courage. In addition, as Richard Holmes argues in Firing Line, soldiers feared being labelled as a coward in front of their comrades, and this was almost certainly a factor with the Manchesters as well.92 One should also consider the influence of Victorian society's ideas regarding the ideal of heroic, martial masculinity, where men were expected to be courageous, honourable, chivalrous and eminently patriotic.93 Hence, few men would openly undermine society's expectations of them.

There were, however, participants who chose to describe the battle in more harrowing language. During other engagements of the war, some soldiers in different regiments admitted openly to feeling afraid or perturbed when coming under fire.94The Manchesters were no exception. Private Stokes, for instance, stated that 'it was fearful to see our own comrades shot down beside us'. Indeed, the man next to him was shot through the head.95 Albert expressed deep sorrow about the loss of his comrades, writing: 'I have seen over thirty men of my regiment shot dead on the spot; [including] plenty of my chums who come from Manchester'.96 The death toll was closer to 11 or 12, but Albert was taken immediately to a hospital after the battle, so he was probably unaware of the final tally. In addition, it was often felt that the number of dead was higher than it really was in the confusion and terror of combat. For Corporal Kelly, the battle was clearly a terrifying ordeal. He writes:

... the only thing I hope is that I don't have another day like my last. One of the Generals said he never thought we could do what we had done with so few men. We had only four officers to come back with us.97

In fact, five out of 10 or 11 officers were wounded that day,98 but Kelly's phrasing certainly enhanced the sense of achievement he and others must have felt. Private Hardicre wrote:

I got through all right, but it was a horrible sight. We thought we would have all got cut up, but our regiment showed the Lancashire pluck, and they [the Boers] flew, and then we mowed them down. We lost 16 men out of our company.99

Again, one can sense an element of pride in this statement. The more formidable the enemy was, the greater the 'glory'.

There is one letter, by an unknown soldier, which provides an exceptionally good description of being under fire. Although some details may be fanciful or exaggerated, it manages to convey an effective image of what combat felt like for this individual, and how he chose to express it. Of note is the effort he made to keep together with Sergeant Lloyd, as if desperate not to be left alone, and that he did not simply abandon Lloyd when he was wounded. His concern and empathy for a comrade are striking. They did not simply rush headlong into the enemy position but tried to maintain cover throughout. This challenges a contemporary fantasy, as expressed in some newspapers, that 'in the Battle of Elandslaagte the British soldiers absolutely refused to take cover, flinging themselves against the enemy with desperate courage':100

The Boers were about a mile in front of us then, behind a large mountain and we were all spread out. One dare not look up, as shots were simply coming in torrents over the top of the hill. Sergeant Lloyd and I were lying behind a rock together. Then the General gave the order that the whole force was to charge ... we all went on our own then, though keeping together as much as possible. Lloyd and I never parted ... we were running and firing for the whole mile, dodging behind rocks as much as possible. Men were dropping all around us. Lloyd and I got within 300 yards [274 m] of them, when Lloyd dropped, shot through the arm and thigh, poor old chap. He begged me not to leave him. I took off my coat and tore it up for bandages. While I was bandaging his leg a shot passed through my helmet. Then another came and passed through the calf of poor Lloyd's other leg. Poor old chap, I could have cried for him. He stuck to it like a brick, and never murmured once. I got him on my back and carried him behind a large stone. Then I had to go and join my company, which by now had got to the top of the hill.101

The accounts discussed thus far have focused on how it felt to be under fire, but there is just one description of how it felt to be hit. Captain Paton, while encouraging his men by waving his sword and revolver, was hit just before the final charge was sounded, and he described it as being 'suddenly knocked clean off my legs by what appeared to me at the moment to be a violent kick from behind'.102 He initially had no idea that he was wounded and when he tried to stand, found his right leg unresponsive. It was only when he saw the blood that he realised he was wounded. Richard Holmes found similar descriptions of this sensation in accounts by soldiers in nineteenth and twentieth century conflicts, where men described being wounded as being felled by someone wielding a large club, or of being kicked off one's feet by someone wearing heavy boots. It was usually the presence of blood which made them realise they were wounded.103

Enough men escaped harm, though, and the Manchesters prepared for the bayonet charge. The bayonet charge has always been the subject of feverish imagination and anticipation for soldiers, and the Manchesters proved to be no exception.104 This is not surprising, given the prevalence of the ideas of heroic and martial masculinity in Victorian society.105 It was believed by some that a man's moral worth, skill, strength, and aggressive spirit could be affirmed and encouraged during a bayonet charge, and this idea persisted well into the twentieth century.106 Also of note was that, as late as the 1890s, prominent British military theorists still regarded an infantry attack with bayonets as the primary tactical means to conquer a position. However, some officers began to realise on the eve of the South African War that modern firepower made bayonet charges an extremely costly proposition, a view which provoked fierce debate in British military circles.107 The debate remained unresolved, though, and thus the men's training still included bayonet drills, which no doubt spurred their imaginations.108

Consequently, despite the deadly promise of modern firepower, the image of the bayonet as the supreme offensive weapon was still part of the military culture which influenced the Manchesters and other British units at Elandslaagte. Private Wall recounted the bayonet charge with relish, stating that 'with a wild cheer we rushed upon them, cutting them down right and left. We did not leave one of them to tell the tale.'109 Similarly, Drummer Toomey recounted with enthusiasm:

I and the big drummer got orders from Colonel Ian Hamilton to "sound the charge". Our men at once fixed bayonets; up came the Gordons, and with one British cheer they went at them. The Boers were frightened at [the sight of] the bayonet[s], and retired with heavy loss.110

More level-headed sources, such as the battalion's Record of Service, paint a different picture of the bayonet charge, where most of the enemy had already withdrawn and the few remaining Boers quickly surrendered, barring a few stubborn individuals. One of the Manchester lieutenants confirmed this image of the final charge: '...they were completely beaten when they saw the bayonets, and begged for mercy, some throwing down their arms, and allowing themselves to be taken prisoners, others fleeing like a flock of sheep'.111 As cited by Richard Holmes in Firing Line: 'The man almost invariably surrenders before the point is stuck into him.'112

The realities of the bayonet charge did not really allow for the masculine ideal to present itself, but the men could display their prowess by out-performing other regiments involved in the attack. There were a number of comments in the letters indicating a strong sense of regimental rivalry, and they reinforce Pakenham's brief mention of this aspect in his description of the battle.113 One man expressed pride in the fact that the Manchesters were in the lead when the final assault was launched.114

Another comment was made by an unknown officer who claimed that 'N__ [sic] and I captured a gun, after an exciting race with the fife major of the Gordons'.115 He was probably referring to Adjudant Newbigging, since the Record of Service stated it was he who reached the guns first. The regimental system helped to foster a sense of loyalty, comradeship and pride in the men who served in these regiments.116

Competition between regiments was thus commonplace, such as leading an attack, or capturing valuable enemy positions or equipment. Richard Holmes makes the argument that since the rise of artillery, these weapons were valued by their operators beyond their actual military value, as 'the ties between the piece and its servants can easily assume mystical overtones'.117 The exaggerated importance given to artillery pieces was not lost on the common infantryman. Capturing the enemy guns was regarded as a great honour. During the infamous white flag incident (discussed below) the Manchesters lost possession of the guns, and the Gordons reclaimed them.118 The Record of Service clearly thought that the honour should go to the men who reached the guns first.119

When the Boer guns were captured, it seemed the battle was won, because some of the Boers raised the white flag and a ceasefire was called. This was, however, an unsanctioned surrender by a few individual Boers, and caused considerable controversy. Some of the last remaining Boer fighters, especially those on the conical hill beyond the Boer camp, continued to fire, and a small but fierce Boer counter-attack was launched. According to some sources, a rout of the British nearly ensued, and casualties were sustained, but the senior officers, especially French and Hamilton, were able to calm the men and repulse the Boers.120 In the course of this incident, the Manchesters' Adjudant, Newbigging, was wounded. The Record of Service adopts a neutral tone regarding the incident, and it appears the author was of the view that some of the Boers were unaware that the white flag had been raised and must have thought the British advance was checked, and hence decided to counter-attack.121

Whether or not this occurred in error, some men were outraged by the incident. Private Evans minced no words, stating that the Boers were the 'biggest cowards on the face of the earth'.122 This sentiment is echoed by Captain Paton, who explained:

...when they [the Boers] saw the cold steel at their chests they threw down their rifles, and as soon as our fellows ceased, they picked up their rifles and fired at them from behind. I don't fancy our fellows will give much quarter next time.123

An unnamed British officer claimed that:

... a man came [forward] with a flag of truce in one hand while he fired left and right with his revolver in the other; while others kept on firing at us till within 15 yards [13,7 m], and then surrendered. Can one wonder if Tommy shoots them, surrender, or no?124

This implies that some Manchesters shot or bayoneted Boers who attempted to surrender, which, given the confused circumstances might have happened, because the men were in a heightened emotional state. Paton was especially upset by the rumour that Adjudant Newbigging was wounded while accepting the surrender of a Boer prisoner, whom he had in fact saved from being bayoneted.125

It is worth noting that Paton did not witness any of these events, since he was wounded before the final charge. However, the officers certainly talked among themselves in hospital, and even though he never saw these events, he was as indignant about it as those who experienced it first-hand. The perceived abuse of the white flag was particularly galling to a generation raised on martial values which included an emphasis on 'chivalry' and 'courage', and surely reinforced existing perceptions of the Boers as a 'treacherous' and 'cowardly' enemy.126 It is also apparent that shooting or bayoneting an enemy instead of accepting the surrender was considered justifiable if the enemy was perceived as flouting the accepted 'rules' of warfare.

In addition, some British men had strong negative feelings about the Boers. Captain Paton wrote to his mother:

... you can't imagine what brutes the Boers are. They are absolute savages. Some of them were using elephant rifles with explosive bullets, some were using expanding bullets like our Dum Dum, which we gave up as we considered them (the Boers) a civilised nation.127

He also asserted that a party of officers and 20 men were captured close to Elandslaagte when they went to recover the dead after the battle, and thought the Boers 'absolute devils'128 as a result. Another officer suspected the same, writing that 'the burying party under Vizard went out yesterday [23 October] ... they have not been heard of [since], so I expect they are prisoners ... that just shows what the Boers' code of honour is'.129 Similarly, Private Hardicre claimed that 'they [the Boers] are a cruel lot. One of the Boers was shot, and I gave him a drink of water, and when I turned, he shot at me, and I turned around and stabbed him to death'.130

It is impossible to know if all the events described did indeed occur, yet it does reveal the attitude some of the Manchesters had towards the enemy. The portrayal of the Boers as 'savages' or 'uncivilised' was likely a reflection of the pervasiveness of nationalist and Social-Darwinist views in Victorian society.131 In addition, soldiers have the tendency to dehumanise the enemy, which helped them to rationalise the killing of other human beings.132 If Hardicre's account is true, then it is a chilling example of how men justified killing others, stabbing them to death in this case, which was probably also driven by a potent emotional cocktail of adrenaline, fear, anger and prejudice.

However, not everyone viewed the Boers so negatively. Captain Melville informed a reporter that 'it was nonsense to state that the Boers were cowards for not coming out into the open. That was part of their tactics. They fought and retreated, to fight again'.133 There is a hint of admiration in this statement. Others had more conflicting opinions. One of the Manchester lieutenants wrote a somewhat complimentary line, followed a short while later by one with a more disdainful tone, that 'the Boers fought hard and well until we came to close quarters ... when they are beaten, the Boers are awful cowards; they are like a lot of whipped curs'.134 It appears that the lieutenant was unsure of how to process the tactical philosophy of the enemy.

The battle's aftermath

Shortly after the last shots were fired, darkness descended and the Manchesters spent the night out in the open in the midst of the carnage. Arguably, for those who survived, spending the night on the battlefield was more terrifying than the battle itself. It is likely that the physical discomfort which prevented sleep encouraged the men to mull over the stressful experience they had just endured. Their thoughts and mood were no doubt influenced by the moans of the wounded and the dying, thus accounting for an almost universally negative portrayal of that particular night. Drummer Toomey writes:

... shortly after the engagement it turned pitch dark, and it was horrible to think of the poor boys lying around us - dead, dying, and wounded ... not a bit of sleep could we get for the cold and the rain and the moaning. One poor officer of the Gordons, who was wounded in three places, lay near me all night, and to make matters worse I could not get a drink of water until morning.135

However, Toomey's letter was published in another newspaper a few days later, on 29 November 1899 in The Aberdeen Weekly Journal, with a few minor differences in the text. In this case, Toomey's letter explained that he could not get any water to give to the wounded Gordon officer.136 Similarly, Bandsman Powell recounted to his friend, Tom, that darkness descended as soon as the battle was over, and the men had to lie among the dead and the wounded. 'We could not sleep', he wrote:

...because it was so wet and cold, and we had nothing to eat for 24 hours, and not even a drink of water. We had to sip water out of the stones to quench our thirst. I should not like to go through the same thing again.137

Another of the unwounded officers had this to say:

...the most horrible part came afterwards . in the dark in the pelting rain and wind. You cannot possibly imagine anything more pitiful than to sit out there all night and hear Tommy's [sic] loud bragging, mixed with the groans of the wounded and dying.138

Some tried to help the wounded in the dark. Private Wall described that

...of course, we had to patrol the battlefield all night, picking up the wounded and burying the dead, and it was the horriblest [sic] sight I ever saw in my life - Boers, horses, and a few of our men scattered about like dead sheep.139

Those who were wounded no doubt experienced far greater pain and suffering, although some were comforted by their fellow soldiers. Captain Paton, who had been hit in the leg, recalled in a letter:

... night was fast closing in, and a steady drizzle had commenced, and as usual in this place the cold became intense. ... Firing was still going on in the distance, and from time to time five or six shots were fired at us on the battlefield by some brutes ... all the field around seemed covered with men groaning in agony, or calling for an ambulance in vain. I prefer to say no more of that night on the field, for it is best forgotten.140

His unwillingness to talk about the ordeal might have been a form of self-censorship to spare his mother from further worry, or perhaps it was simply impossible for him to convey the experience in words. He was fortunate, however, in having help and company.

We are told in another letter that Paton wrote to a fellow officer in Manchester that one of the men, Private Rogers, stayed with Paton throughout the night of the battle and 'did all in his power for me, ... I shall never cease to be grateful to him. I am jolly glad he spotted me as he came straggling back after the charge'.141Paton's 'anonymous' letter in The Manchester Guardian provides a few more details, on how Rogers kept him warm by covering them both with his military-issue great cloak and then hugging Paton for much of the night.142 This is an example of camaraderie and empathy as expressed on the battlefield, something seldom recounted in more conventional accounts of military action.143

On the sight that met the Manchesters at daylight the next morning, comments expressed a combination of revulsion and horror. Some sought to help the wounded. An unknown officer, for example, wrote of how he was set to work to help the doctors in the field and 'found two chaps in the Gordons whom I knew fairly well... [both were] stone dead within twenty yards [18,2 m] of each other'.144 Drummer Toomey also joined in the search that same morning.145

As discussed earlier, some men did not readily admit to fear in battle, but evidently it was acceptable to convey horror at the sight of death. Bandsman Powell described it as 'rather a strange sight for Sunday morning to be going in search of our comrades who were killed or wounded. Some had almost their heads blown off ... it was too horrible to describe'.146 Another soldier wrote with empathy:

Oh, God, what a sickening sight! On the top of the hill, one could not step without falling over a dead Boer or a wounded one. I spoke to one poor fellow [a Boer] who was shot through the chest and offered him a drink, but he would not have it, for he thought it was poison.147

Private Evans was horrified at the carnage, writing that 'such a sight' was enough to 'make the bravest man quiver'. The dead and wounded [Boers] and their horses were evidence, he wrote, that 'our artillery had done some good work'.148

Private Little focused on the plight of the horses, writing that this was his 'first battle'. He added that it was horrible to see the sights after daybreak. Previously, he explained, 'I could not look at a dead horse', but the scene before him would, he was sure, 'harden anyone on the battlefield'.149 It is fairly common in modern warfare for some soldiers to be more disturbed by the sight of dead animals than of slain men. According to Richard Holmes, the likely reason for this is that animals, unlike men, had little agency in war and were therefore regarded as the innocent victims of 'human savagery'.150

Added to the grim images of the aftermath of battle, some soldiers had to face their own wounds, as well as those of their comrades. Some wounds would lead to life-long pain and suffering; possibly even deadly consequences. Private Little wrote to his sister of the pain of loss:

I am very sorry to tell you poor old Ned Dewhurst was shot in the head just as the fight ended. I got three chums to help me, and we carried him on our rifles . and sat with him all night in the rain, expecting every minute to see him die, but he lived until morning, and then died.151

Private Evans described a terrible, but not fatal neck wound and relayed that the bullet had travelled nearly fourteen inches (35.5 cm) down his back. He also mentioned that 'we lost 12 killed and 30 wounded, some of whom will die, and others disabled for life. There was a comrade of mine just had his left arm taken off. His name is Dainty'.152

A soldier named Albert wrote to his parents saying that he was 'very sorry to let you know that . I happened to get shot in the left hand. 'The bullet went through the palm of my hand ... [but] I am glad to say that no bones were broken'.153 Sergeant Lloyd, who suffered three hits, survived. The soldier who was with him reported that Lloyd was 'getting on grand; he is out of danger, though I am afraid he will have to have one of his legs taken off'.154

Several officers were wounded, including Paton, who wrote 'I got hit on the inside of the thigh ... and they cut the bullet out of my right hip joint. How it got there I don't know . it has broken nothing, and I have got the bullet as a trophy'.155 Paton also described the wounds of several other officers, writing that 'Melville suffered a broken arm after a Mauser bullet hit his right bicep, while Adjudant Newbigging sustained a wound in the shoulder, and the bullet had exploded out of his back'. Paton was sure it was an explosive bullet, but as John Keegan states in The Face of Battle, an explosive exit could also be caused when a bullet hits bone. Sergeant-Major Haddon added that Lieutenant-Colonel Curran, the commander of the 1stManchesters, was shot through the shoulder, and that Lieutenant Danks was shot through the cheek.156 Danks's injuries were serious. Paton wrote that 'Danks I am afraid is rather bad, and there was a talk of surgery to take the pressure off [his] brain. [He added] I hope he will be alright, for he is a very good young fellow'.157 The Record of Service adds that Danks later died from his wound on 31 May 1900, seven months after the battle.158 In all, five of ten or eleven officers were wounded, indicating that leading from the front, while conspicuously armed with a sword and revolver, made the officers a prime target.

Being wounded was always a possibility and several men thought that becoming a casualty was more a question of luck or divine intervention than any inherent skill at dodging bullets. Bandsman Powell, after he had time to reflect on the battle, was of the opinion that he was 'lucky to be alive'.159 Private Little wrote that he had thus far 'managed to escape [bullets]'.160 His tone indicated an awareness that he might not be as fortunate in future. Private Stokes stated that 'it is all luck; you don't know what you are doing when you are fighting'.161 Private Evans was not as lucky, but fortunately for him his wound was not life-threatening, and he thought he led a 'charmed life'.162Another soldier, Albert, wrote that 'after seven hours of hard fighting with the Boers, I think myself lucky that I escaped with such a slight wound [his left hand]'.163 Similarly, Captain Paton thought 'it was rough luck getting knocked over in the first engagement ... [the bullet] just missing the femoral artery by a hair's breadth. Jolly lucky, wasn't it, that it wasn't a quarter of an inch higher?'164 He also gave thanks that he was lucky enough not to lose his leg, since he knew of several others who had limbs amputated after the battle.165 Corporal Kelly wondered 'God knows how I had escaped being shot', [because the] 'bullets were whizzing all ways'.166

The Manchesters' letters reflect that they had varying opinions of their regiment's casualty rate and whether the price they paid for victory was worth it. In all, a combination of poor luck and successful enemy marksmanship caused them to suffer between 10 to 14 deaths and 29 to 32 wounded,167 which was roughly 13 per cent of their strength at the commencement of the battle. Private Wall suggested that their casualties totalled 'only' 11 dead and 36 wounded, and he clearly considered this was negligible.168 Another of the soldiers shared Wall's opinion, writing 'our regiment did not lose many under the circumstances ... twelve were killed and 50 wounded'.169 Private Evans, in contrast, regarded the 12 killed and 30 wounded as indicative of a 'hard fight', and that a 'heavy price' had been paid.170 Private Little echoed Evans's sentiments.171 Corporal Kelly, who led a section of 20 men, revealed a sense of satisfaction at victory, but expressed dismay at the high casualty rate, writing: '.we charged them ... and paid them well out, but I am sorry to say we had very few left when it was finished'.172

Heavy casualties inflicted during frontal attacks were common in the first months of the South African War, largely because of the impact of modern weaponry which gave a decisive advantage to defenders, especially when in good cover or trenches. This trend was repeated in the First World War. It appears that the lessons of the South African War were not fully realised, and costly frontal attacks persisted.173

There is little doubt that the battle was a clear British victory, although the men interpreted its significance in various ways. Private Little, writing in the aftermath of the battle, regarded the victory as one 'dearly bought [because many] of the Queen's soldiers were killed or wounded'. As he put it, 'you can bet your life we shall beat old Kruger in the end, but there will be a lot of lives lost'.174 In contrast, Private Evans, despite being cognisant of their heavy casualties, had a more optimistic opinion, stating: 'I think this war will not last above another two or three months, as we are beating them everywhere we meet them'.175 In the end, the pessimists were proven right.

The aftermath of the battle had some positive aspects. There were a few reasons for joy, apart from feeling elated about surviving. For at least two soldiers, who were brothers, happiness came when finding out they were both alive and well after the fighting. The one brother wrote that he enquired about his brother Bob's whereabouts, and to his joy:

I found him at last, after shouting his name for twenty minutes, sitting as contented as one wished to be, on the body of a dead Boer smoking a fag. He jumped up and rushed over to me with his arms out, surprised, saying he had just been having a good cry, for he had been told I was shot. So, you can guess the handshake we gave one another.176

Another cause for celebration was plunder. In his 1969 history of the battle, Breytenbach takes the opportunity to condemn the behaviour of the British soldiers,177 although there is no indication in the men's accounts that looting was regarded as morally reprehensible at the time. The Queen's Regulations and Orders for the Army, 1899 has nothing to say about looting the enemy after a successful battle. Furthermore, the attitude of the men and officers clearly showed a distinct lack of concern. According to the Army Act of 1881, 'plunder' was severely punished when a soldier was on active duty. Under S-6 - Offences punishable more severely on active service than at other times, the Act stated that a soldier was to be punished if he 'leaves his commanding officer to go in search of plunder' or 'breaks into any house or other place in search of plunder'. The penalty was death or a lesser punishment. In this instance, it appears that looting the defeated enemy was condoned.

The plunder gained from victory and the relief of seeing comrades alive contributed to the post-battle euphoria of the Manchesters. The evidence shows that Bandsman Powell managed to procure several sets of underclothing for himself.178

Private Evans expressed regret, due to his wounds, that he was unable to 'join the fun'179 when his comrades helped themselves liberally to captured provisions. As he was carried past his fellow soldiers on a stretcher, 'they gave me a hearty greeting because I had earlier been reported dead'. By this time the Manchesters were assembling near the train, preparing for the journey back to Ladysmith and Captain Paton noted that the men were all in good spirits chattering and laughing. They were 'gloriously happy', the reason being that they had 'captured three big guns, two of the enemy's flags, and as many rifles, pistols, bandoliers, stores, blankets, provisions, ... as they could carry. They gave me a hearty greeting as I was carried past them, for I had been reported dead'.180 Toomey, who wrote his letter on a piece of paper looted from a Boer, related that 'we waved [the standards] joyously on our way back home [to Ladysmith] and on the landing at the station we were loudly cheered by the civilians'.181

Conclusion

Most accounts of the South African War focus on political events, strategy, tactics, or provide a narration of main events during the campaign. Few emphasise the experience of the soldiers who engaged in battle. This article seeks to highlight these experiences and emotions by studying the accounts written by the Manchester Regiment who fought in the Battle of Elandslaagte. The article provides fresh insights to supplement existing narratives of the battle by exposing the 'face of battle' for the men of the so-called 'Fighting First' in the South African War. This same approach could be used to good effect to analyse how other regiments experienced the war.