Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Historia

On-line version ISSN 2309-8392

Print version ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.67 n.1 Durban May. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8392/2022/v67n1a6

ARTICLES

Hunger and power: Politics, food (in)security and the development of small grains in Zimbabwe, 2000-2010

Bryan KaumaI; Sandra SwartII, *

IResearch Fellow at Stellenbosch University and lecturer in African History at Durham University

IIProfessor in the History Department at Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

White maize sadza is the most eaten food in Zimbabwe. Yet, over the decade of the 2000s, its consumption was threatened by drought and consequent acute food shortages. Small grains - sorghum and millet - offered a panacea to looming starvation and civil unrest. Yet, as we argue in this article, its access became rooted increasingly within political contestations between the ruling ZANU PF government, the budding opposition party and ordinary citizens. Using the story of small grains -sorghum and millet - between 2000 and 2010, we trace how food (in)security took a political form, stirring a pot of sometimes violent clashes between political and social contenders. We argue that through 'political grain', various political and social elites were able to amass wealth and power for themselves and grab control of sociopolitical discourse on food security during the crisis years. As the state imposed a series of seemingly well-intentioned and sometimes even widely welcomed food initiatives such as Operation Maguta and BACOSSI, these food security measures were often ad hoc, temporary and - as we argue - actually had an adverse long-term impact on local grain production and food availability. The government worked through key parastatals like the Grain Marketing Board and the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe to allocate resources and food support to ruling party loyalists. In this period, the ZANU PF regime was concerned primarily with holding on to its waning political power and avenues for personal wealth accumulation at the expense of food security in the country. This paper demonstrates how an anthropogenically-induced 'hunger' effectively prolonged ZANU PF's control of society - but we also show how 'small people' fought back against President Robert Mugabe's 'big men' by embracing the growing and eating of traditional 'small grains'.

Keywords: small grains, millet, sorghum, rapoko, maize, food history, food security, ZANU PF, FTLRP, Mugabe, Zimbabwe.

OPSOMMING

Witmielie-sadza is die stapelvoedsel van die meeste mense in Zimbabwe. Tog, oor die dekade van die 2000s, is die verbruik daarvan deur droogte bedreig met gevolglike akute voedseltekorte. Kleingrane - sorghum en rapoko - het uitkoms vir dreigende hongersnood en burgerlike onrus gebied. Maar soos in hierdie artikel geargumenteer word, het die toegang tot kleingrane toenemend verstrengel geraak in "n politieke stryd tussen die regerende ZANU PF-regering, die ontluikende opposisieparty en gewone burgers. Ons gebruik die verhaal van kleingrane tussen 2000 en 2010 om aan te toon hoe voedsel-(on)sekerheid 'n politieke vorm aangeneem het, wat gewelddadige botsings tussen politieke en sosiale aanspraakmakers / mededingers aangestig het.

Ons argumenteer dat verskeie politieke en sosiale elites in staat was om rykdom en mag te bekom en beheer oor die sosio-politieke diskoers rondom voedselsekerheid tydens die krisisjare uit te oefen. Hoewel die staat 'n reeks oënskynlik goedbedoelde en soms selfs populêre voedselinisiatiewe soos Operasie Maguta en BACOSSI ingestel het, was hierdie voedselsekerheidsmaatreëls dikwels ad hoc, tydelik en het ironies genoeg 'n nadelige langtermyn-impak op plaaslike graanproduksie en voedselbeskikbaarheid gehad. Die regering het deur belangrike semi-staatsinstellings soos die Graanbemarkingsraad en die Reserwebank van Zimbabwe gewerk om hulpbronne en voedselondersteuning aan regerende partylojaliste toe te ken. In hierdie tydperk was die ZANU PF-regime hoofsaaklik gefokus op die behoud van sy kwynende politieke mag en manière vir persoonlike verryking ten koste van voedselsekerheid in die land. Hierdie artikel demonstreer hoe 'n antropogenies-geïnduseerde 'hongersnood' ZANU PF se beheer oor die samelewing effektief verleng het - maar ons toon ook aan hoe 'gewone mense' teruggeveg het teen president Robert Mugabe se 'groot manne/elite' deur 'kleingrane' te verbou en te verbruik.

Sleutelwoorde: kleingrane, sorghum, rapoko, mielies, voedselgeskiedenis, voedselsekerheid, ZANU PF, FTLRP, Mugabe, Zimbabwe.

Introduction

'Man-made starvation is "slowly making its way into Zimbabwe" and most households in the country are unable to obtain enough food to meet their basic needs.'1 United Nations Special Rapporteur, 28 November 2019.

'...there is no such thing as an apolitical food problem'.2 Amartya Sen

Political commentators observe, with dark humour, that the 'breadbasket of Africa' had become a 'basket case'. As we write, many people are starving in Zimbabwe.3Owing to a convergence of ecological, economic, and political factors, hunger became a reality for many people at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Zimbabwe was undergoing a series of socio-economic and political upheavals, while also faced with growing food demands. Meanwhile, the government took derisory steps to address widening hunger and food insecurity.4 This state of affairs was more acute across rural areas, and notably, those considered as 'opposition strongholds.' There were dwindling national grain harvests for what has become (for a set of historical reasons) the country's staple - maize. Yet in stark contrast, as we will demonstrate, this same period saw steady growth in the cultivation of traditional 'small grains' - sorghum, millet and rapoko.

Against this background, this paper explores how by neglecting the development of small grains in preference for maize, various political interests fuelled widening food insecurity from the start of the "Third Chimurenga" (land reform programme) in 20005 until the end of the decade, two years after the signing of the Global Political Agreement between Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU PF) and the two main Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) formations in September 2008. We argue that food insecurity during this period was largely an anthropogenic and politically-induced crisis, spurred on by a combination of calculated and unintentional interventions intended to further the political and economic interests of elite factions. Thus the 'slow violence' of climate change underlines the problem, but the 'sudden violence' of the Mugabe regime saw food instrumentally manipulated to consolidate its power over the black Zimbabweans and settle scores with white Zimbabweans. We also then show how various elites politicised food aid, shrewdly used the looming food crisis to amass capital - both political and financial - for themselves.

Using a range of primary sources, including articles from various newspapers including The Chronicle, The Herald, The Standard and the Zimbabwe Independent,6secondary literature and our own oral history interviews with some Zimbabwean farmers and consumers of small grain in the Midlands and Matabeleland region, government officials as well as knowledgeable persons, we revisit what historian Lloyd Sachikonye described as Zimbabwe's 'lost decade' - this time through the stomach of the nation.7 We explore Zimbabwe's battle with food insecurity showing how through state-controlled parastatals such as the Grain Marketing Board (GMB) in particular, the Mugabe regime's romanticised domestic agrarian discourse, which was an effort to counter international perceptions of Zimbabwe after land reform. We show how individuals within the ruling party systematically leveraged the crisis to augment their personal wealth while settling political scores against the opposition and its supporters.

We also show how some in communal arid areas relied on small grains, greatly reducing their general reliance on government handouts. But, in contrast, the state encouraged a 'maize complex' - so from 2002, maize farmers who continued to suffer from declining yields owed their survival to the continued benevolence of the ruling ZANU PF. We observe how, for the regime, small grains (unlike maize) represented the social and political dissidence that constrained their options during state-making and challenged their omnipotence. We contend that ZANU PF used the GMB to gratify cartels who served the needs of the politically -connected.8 Moreover, the GMB monopoly over grain production and distribution worsened the impoverishment of African families deliberately through the perpetuation of low market prices for small grains, thereby intentionally deterring their cultivation in place of maize to maintain citizen reliance on government support for their livelihood. An anthropogenic 'hunger' effectively prolonged ZANU PF's dominance over society.

We divide this discussion into sections arranged thematically beginning with a succinct historiographical review of food security in Zimbabwe. We then examine the Fast-Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) years, showing how the politics of the programme inadvertently shaped the growth of small grains and food security. In the remaining sections, we focus on key themes including the politicisation of grain and food assistance by political elites, corruption and mismanagement of state resources and agencies, social marginalisation of opposition supporters - as well regions where the opposition enjoyed a seeming political majority advantage. We show how these posed obstacles to food security over time and demonstrate that food (in)security is political, as economist Amartya Sen observed.9 Moreover, we extend historian Tapiwa Madimu's contention that during periods of crisis the ZANU PF government made persistent use of the prevailing (food) crisis to consolidate its political power and control the socio-political narrative within the country.10 We show how the development of small grains during the decade was a contest by power hungry political interests aimed at maintaining their grip on power against hungry families looking to fill their stomachs.

State making, food (in)security and history

Globally, and indeed for Zimbabwe, there is a growing literature from various disciplines including economics, agricultural/environmental science and history exploring food security. Up to the early 1980s, food security epistemology was grounded within classical Malthusian ideas about the relationship between population growth and food production.11 The reasoning was that food availability declined inversely with a correlated increase in population. However, over the last two decades, the literature and outlook have both expanded. Discourses on socio-environmental change, global warming and climate change,12 political shifts including land reform programmes,13 social movements such as food riots and protests,14 and the outbreak of pandemics and proliferation of aid relief15 have all in varying ways contributed towards fresh perspectives on the roots, nature and impact of food security.

We show that the subject of food security is not a new phenomenon and has long featured in both colonial and postcolonial conversations on agrarian and labour history.16 The World Food Programme defines food security as the state of being able to feed oneself from one season (often measured in terms of agricultural seasons but refers more flexibly to periods between incomes17) through to the next.18 The evaluation of food security at the national level is based on the total amount of the main staple - maize grain in the case of Zimbabwe - in the country during a specified period in relation to the demand.19 This 'maize unit' for Zimbabwe has not only been problematic but has proliferated patterns of unfair control of the citizenry by the ruling regime. Food insecurity means the inability by society to access affordable and nutritious food at any given time throughout a measured period of time.20 What is important to note is that copious scientific literature from the 1980s onwards has underlined small grains as the ideal crop to combat the risk of food insecurity across Africa and Zimbabwe in particular, because of its drought-resistant characteristics.

The UN maintains that hunger 'arrived' in Zimbabwe in 2004 - but, of course, it has a much longer history. Historian John Iliffe has explored various droughts in Zimbabwe from the early colonial era since 1911, underlining how the roots of famine differed over time.21 Tinashe Takuva builds on this conversation to argue that in Zimbabwe, droughts have a deep-seated political history - instigated and manipulated by the state.22 In some cases, drought was a result of low rainfall patterns, while equally true for 1932, 1947, and post-2000 drought - as we shall demonstrate - poor food policies have contributed to African hunger and starvation.23Vaughan, Iliffe, Takuva and Sen underscore the different shades of human-made or anthropogenic droughts and their socio-political ramifications for society. The scholarly focus on food has shifted towards the structure of access, control and distribution of food resources. We build on Jean Francois Bayart's seminal Politics of the Belly24 to analyse the conflict between what we view as 'big men' versus 'little men', politicians and grain cartels versus hungry communities. This extends 2013 work by historians Alexander and JoAnn McGregor, which argues that patronage politics eroded agrarian development because of intimidation and partisan distribution of food.25

Monopolies play a crucial role in shaping food security. Economist Priscilla Masanganise and historian Victor Machingaidze concur that agricultural monopolies create commodity-marketing boards that stifle natural sectoral growth by relying heavily on government subsidies to remain afloat.26 For as long as these boards continue to be bankrolled by the state and serve the economic and political interests of the ruling elites, their existence is guaranteed. In Zimbabwe, through the appointment of former military and party loyalists to top positions in parastatals, organisations such as the GMB were neatly under the control of ZANU PF and similarly gratified cartels to serve the needs of the minority elites within the party.27Moreover, we argue that through a purposeful GMB monopoly, ZANU PF exacerbated the impoverishment of African small grain farmers through its perpetuation of low market prices for small grains over maize, despite the growing local and global markets for the former by the mid-2000s. This was to deter - with purposeful intent - their cultivation in some areas to maintain political face in the aftermath of the haphazard farm invasions in the early 2000s. This cycle of poverty fuelled the politicisation of food during the crisis-era from 2002 onwards and enabled the government to consolidate its power.28 Building on the work of historians Stein Eriksen,29 Madimu30 and Muchaparara Musemwa,31 we argue that during the 2000s, food insecurity was appropriated as a key tool by the Mugabe regime in consolidating power by leveraging African hunger in exchange for political allegiances. Furthermore, by establishing 'political grains', between 2000 and 2010, Zimbabwe suffered from a 'state-induced famine.'32

The Fast-Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) and its impact on the grain production, 2000-10

A key moment that laid bare such power relations was the FTLRP.33 Scholars have examined how this programme had multiple social and economic consequences for society34 and agriculture.35 The ad hoc land grabs generated much global criticism -as noted by Jocelyn Alexander, 36 Rory Pilossof 37 and Angus Selby. 38 They demonstrate how, emerging from ostensible land reform initiatives, the state enforced an authoritarian and militaristic approach towards ordinary white farmers and black and white critics as well as burgeoning voices for political change. Yet, there are several conflicting academic opinions on the nature and impacts of land reform exercises and FTLRP in Zimbabwe in particular.39 However, it is generally agreed that the FTLRP transformed commercial agriculture. Many critics add that the worsening of Zimbabwe's social, economic and political crisis has its roots within this land redistribution exercise.40 Soon after its implementation, domestic agriculture was burdened by economic sanctions imposed by Britain, the United States of America and all fifteen members of the European Union (EU), which came at a time of successive years of low rainfall with concomitant lowered agricultural productivity. The post-2000 era was marked by political unrest in response to the shrinking economy characterised by hyperinflation. 41 Because of trade restrictions and increasing foreign currency deficits to import implements and food, by 2002 the state of food insecurity worsened through a lack of capacity to produce enough grain for domestic consumption.

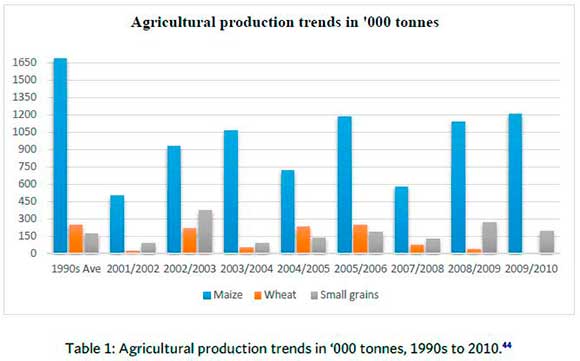

Even at the peak of crisis between 2007 and 2008, as demonstrated in Table 1, small grains faired relatively well, unlike other crops such as deciduous fruits, wheat and especially maize. In part, this was largely because of their environmental suitability to withstand the prevailing dry climate, as well as how for most of the time throughout the postcolonial years, the development of small grains did not rely on any direct government support. Unlike maize and tobacco, for example, small grains managed to escape the daunting government administrative red-tape and official low market prices that regulated production and distribution on the formal markets.42 Instead, small grains attracted a growing informal domestic market, thereby being impacted to a lesser extent by the international trade sanctions imposed on Zimbabwe.43 Added to this, growing health and 'food basket' affordability concerns - across poor families and across the country - triggered growing interest in the consumption of small grains.

Contrary to the tag 'the lost decade' ascribed to the period from around 2000 until 2010, insofar as small grains production is concerned, as shown in Table 1, we argue that this period witnessed some of the most significant material developments for small grain production during the post-colonial era. The Third Chimurenga saw more than 4 000 white settler commercial farms being repossessed and repartitioned into A1 and A2 estates to benefit over 150 000 African families by 2002.45 This witnessed the gradual dismantling of large commercial maize farms and production into smaller units characterised by fragmented and piecemeal agricultural production. From late 2001, a series of calls for food aid by the government followed. These disruptions contributed towards Zimbabwe's status as the 'breadbasket' of the region reaching an abrupt end. This had been pinned primarily on white commercial farmer production of maize and wheat.46 However, the coming of the FTLRP shifted the impetus of agricultural production through the increased number of small communal plots that became available to be cultivated by individual African families.47 These newly resettled farmers dedicated 78 per cent of their cropped land towards cultivating food grains, including both maize and small grains.48 Because of limited financial capacity as well as the prevailing erratic and low rainfall patterns that characterised the era between 2000 and 2005, many newly resettled farmers were quick to adopt traditional ideas of cultivation such as intercropping and dry planting known as gatshopo across the Matabeleland region,49 which despite their ostensible 'outdatedness', enabled small grains to be more widely grown in comparison to maize.

Between 2002 and 2003, small grains production grew exponentially, in part benefiting from the reduced competition from white maize farmers who had been expelled from their farms.50 Added to this, a boost in grain prices by the GMB in August 2002 of about $30 more per tonne from $220 to between $250 and $280, while reducing the cost of millers' purchasing for local resale by 25 per cent to try and cushion against growing hunger, greatly generated interest in grain cultivation among the newly resettled farmers.51 Small grains attracted farmer interest because in comparison to maize, the seed was often shared communally and therefore, during critical years such as 2003, when maize seed was expensive and scarce on the local market, small grain seed was widely available on both the informal market and through kinship networks.

In the short term, such pricing incentives by the GMB motivated black small-scale farmers to take up cultivation actively despite the handicap of limited capital such as ploughs, insecticides and seeds that affected most of them.52 Operations by the GMB for a while seemed to serve the wider population, yet as we will show in the following sections, coupled with the land distribution exercise and agricultural support and extension services, these were by and large distributed along partisan lines. Equally, in some instances, similar food and implement aid from well-meaning Western sympathisers and organisations was used to propel the opposition campaigns which underlined the disruptive nature of the FLTRP. Yet, it would be remiss to ignore how this was equally part of an ulterior agenda to 'remind' Zimbabweans (and South Africans on the side-lines) of the dangers of forcibly reclaiming the land.53 Indeed, this limitation was exploited by ZANU PF to maintain control over African families through intentionally distributing maize seed instead of small grain seeds, as often requested by local farmers. According to various local and international news media reports including the popular Voice of America, Studio 7, families observed to be growing crops outside those whose seed came from the government were frequently ostracised socially and even targeted as working with the opposition party to defy the government's efforts towards boosting agricultural production, and Zimbabwe's efforts at reclaiming its seat as the breadbasket of the region.54

In the aftermath of the farm invasions, in June 2001, the GMB introduced a new grain trading policy,55 which turned out to be simply an opportunity for major grain heists by senior government officials.56 These elites highjacked the trading of grain using their political influence over key apparatus including the GMB and the Grains Millers Association of Zimbabwe in the acquisition and allocation of grain. Effectively, grain cartels controlled the flow of grain and by the end of 2003, only 15-grain purchase, trading and milling permits had been issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, allowing only a total of about 35 private companies out of over 120 applicants access to buy grain in large quantities directly from the GMB. 57Unsurprisingly, the ownership of these companies was linked to the ruling ZANU PF party or its influential members. Emulating the uneven grain trade tendencies of the 'era of exploitation' on African peasant farmers by oligarchic grain barons following the enactment of the Maize Control Act in 1930, these 35 companies became intermediaries between all the private millers who wanted to acquire subsidised grain from the GMB. Before FTLRP, similar monopolies were controlled by the white Commercial Farmers Union.58 Now, these monopolies were held by 'loyal friends of the party'.59 This gave individuals loyal to the regime full access to Zimbabwe's food supply, enabling them, through the belly, to influence the social and political narrative of society.

At a macro level, access to regional and international grain markets was jeopardised for farmers following the FTLRP.60 As noted above, various Western countries imposed targeted economic sanctions and restrictions on Zimbabwe's leaders and on selected companies operating in and with Zimbabwe.61 This significantly reduced Zimbabwe's export market for agricultural produce, including small grains that were being sold for animal fodder in Britain.62 Large-scale commercial farmers suffered. Moreover, with its foreign currency income streams dwindled significantly as a result of embargoes from global financiers including the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. This meant that the country's access to financial support for domestic development was adversely affected. Export-orientated agriculture collapsed and by 2008 it was virtually non-existent.63 To counter the fast-plummeting grain markets, in November 2004 the GMB initiated various 'contract farming projects' for oilseeds and small grains, within resettlement areas, to complement maize production across the country.64 GMB executive the retired Colonel Samuel Muvuti stated that this new agricultural drive had earmarked 150 000 hectares across the country for the 2004/5 season and boasted that this would provide 'enough food in the country...[and furthermore] there is not going to be a need of food aid.'65

Embraced by different, newly-resettled farmers across the country, as displayed by Figure 1 for example, of government-supported contract small grain farmers, such community projects boosted production of small grains and revived prospects of food security. Apart from enhancing food security in the country, the project, according to Muvuti, also targeted generating forex through the export of small grains, which since the low rainfall patterns across the southern African region from around 2001, were increasingly enjoying favourable attention across the Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries especially in neighbouring South Africa and even a few selected European countries.66 In a follow-up interview the next year, Muvuti remarked how gains from small grains exports were paying off shortfalls for maize and fuel imports incurred by the government.67

At the same time, maize projections proved contrary to Muvuti's predictions. This was a result of a combination of factors including both a prolonged dry spell experienced since around 2001 as well as the expulsion of seasoned commercial white farmers. Thus, while small grains managed to survive and even thrive under the environment, the same was not experienced with local maize as output dropped and Zimbabwe was placed on the UN priority list for hunger and starvation along with Lesotho, Swaziland, Malawi and Mozambique by the beginning of 2005.69 While maize output showed slight increases from 915 m/t to 1485 m/t during this period, small grains witnessed a more significant increase, growing by over 75 per cent from 66 m/t to 164 m/t.70 Notwithstanding, this remained far short of the announced government expectations and, more importantly, the expected yields to feed the nation. By 2002, small-grain cultivation was experiencing growing popularity among several households across the country, arguably as a result of its increased re-emphasis by both NGOs and the government of its nutritional qualities. Countrywide, households affected by the menacing HIV/AIDS pandemic embraced a small grains diet arguing that it helped boost their immune systems.71 Emphasising that small grains had been integral to traditional meals (pre-dating colonial rule), health practitioners encouraged their consumption again.72 Moreover, despite the political contestations that characterised the post-FTLRP period, a great number of the communal farmers were able to get material and educational support on how to grow small grains from the different international donor and religious agencies, including World Vision, ORAP, Catholic Relief Services and the World Food Programme.73However, as the following section will show, this position was short-lived as rumours spread of 'regime change' facilitated by these philanthropic organisations. In the meantime, the relationship between African families and civil society organisations exposed the national policy flaws used by the state in measuring food security - that is using only maize outputs by local farmers and that stored by the GMB in its depots across the country as indicators of the availability of food across the country.

From 2004, although the state made more calls on communal communities especially in the drought-prone regions to grow small grains, it emphasised that it was merely a substitute 'in case maize failed.'74 The Midlands and Matabeleland south provinces responded positively to these calls, with small grain yields improving steadily while maize and wheat yields suffered repeated losses between 2005 and 2008, largely because of adverse climatic conditions.75 For communities who grew small-grain, this improvement reduced their demand for food assistance from the government. Although this eased the burden on the state for food support, in equal measure it reduced state leverage through food and this in part accounts for the open and growing support for opposition politics in these regions.

Small grains, big (electoral) gains

Increasingly from 2004, small grains cultivation and consumption seemed to be widely encouraged by various international organisations. From as early as 2002 these were becoming increasingly vocal in political matters in the country - and increasingly they were suspected of being in cahoots with the opposition MDC. While Mugabe's ZANU PF used the FTLRP as its election trump card, the opposition (which was increasingly aligned to Western powers), benefited from the work of different Western-sponsored NGOs distributing drought relief distributing NGOs across the country.76 Resultant favourable small grain yields, especially during dry seasons, made for very large electoral gains for the new opposition MDC party. This was much to the chagrin of the ZANU PF government which had not suffered such stiff electoral competition since the demise of Joshua Nkomo's PF ZAPU. Moreover, as ZANU PF continued to insist on maize as being the 'real' national crop, the relief that small grains brought to the society was undermining their electoral campaign and rhetoric.

At the same time, because food shortages were not experienced uniformly across the country, electoral grain rhetoric also impacted differently. In some drought-prone regions, like Masvingo province, many remained less anxious over maize shortages compared to those in Mashonaland Central Province. This was because of widespread cultivation and reliance on small grains as opposed to maize.77The same was true in Mberengwa, Zvishavane and Chivi.78 Oral history testimony reveals how by 2000, encouraged by NGOs, small grains were fast replacing maize and wheat among local families. These changes coincided with a series of erratic rainfall patterns that adversely affected maize production as well as the kick-off of the FTLRP. By the time of the 2002 elections, many NGOs operating in drought-prone areas had done a fair amount of information dissemination on the need to cultivate the more ecologically suitable small grains - or face the possibility of hunger. 79 The poor performance of government-supported maize projects immediately after the FTLRP, along with the euphoria of the new opposition party, resulted in poor electoral performance of ZANU PF in the 2000 and 2002 referendum and general elections respectively. With respect to food security, both a drought-induced and politically-induced hunger threatened. However, acute fears over food insecurity resulting from poor national maize yields enabled small-grain production to boom and improved domestic food security.80 For most parts of south-eastern Zimbabwe and parts of Matabeleland North like Binga,81 small grains were no longer considered 'a poor man's crop', despite their negligible economic contribution to the national economy.

'ngokweZANU lokhu':82 The politics of food distribution and allocation

During a ZANU PF election campaign rally in Gwanda in October 2001, Mugabe made an unprecedented move in the history of post-colonial ZANU PF politicking -abruptly ending the party rally without conducting the much-anticipated distribution of food and grain-seed donations which was a quintessential ZANU PF campaign strategy.83 Was ZANU PF so sure of its electoral victory as to risk upsetting the electorate? Indeed, this was puzzling to many including political analyst Ibbo Mandaza, who observed that in the 2002 election ZANU PF was faced with the robust and newly-formed MDC, its toughest political rival since Joshua Nkomo led PF ZAPU in the 1980s.84 Adding to the surprise was the state humiliation in the recent constitutional referendum of February 2000 and the subsequent parliamentary elections in June of the same year.85 In both these contests, the opposition MDC celebrated victories over ZANU PF in Matabeleland South province.86 Significantly, these elections drew attention to the increased cases of local politicians using international food aid to win supporters. Despite various efforts by the opposition to challenge the use of food tokens in electioneering, ZANU PF (through its control over main systems and apparatus involved in food relief) was still able to manipulate and control the flow of food in their favour.87

The most widespread method of doing so was the registering of food and grain-seed beneficiaries with local traditional leaders such as chiefs. It should be highlighted that by 2001 chiefs and other local traditional leadership figures had been co-opted by their inclusion on the government payroll, and for many years they were present at ZANU PF and national functions.88 As with the GMB, the rules became increasingly blurred with regard to the role of traditional leaders in food distribution after 2001. As Toyin Falola observed, those in power tend to reward those who are 'loyal' as well as those with whom they share rural roots and heritage.89 ZANU PF control of traditional institutions became a primary tool in the retention of power. Most local leaders reinforced the 'maize over any other crop' narrative, buttressing ZANU PF's desire to show the world that maize production persisted despite the absence of commercial white farmers. Others, such as a local Binga councillor observed how 'they [government officials] claim huge per diems for their visits...these (maize) handover ceremonies are a chance to rebuke the opposition and chant slogans... people eat for two days but thereafter go back to their dry fields.'90 Securing party allegiance was enforced through control of grain tenure, and in addition, preventing non-ZANU PF supporters from receiving grain aid with the fear of hunger being a key motivation to remain committed to the party by several members.91

In so doing, the Mugabe government successfully re-invented 'political grain', just as the colonial-era Maize Board had done in the early 1930s. Over the next few years, this regime was able to churn out developmental programmes along both party and ethnic lines to punish opposition voices. While never openly admitting to this, several ZANU officials always shifted the blame onto starving populations, arguing that the prevalence of hunger in certain areas was because of citizen apathy and reluctance to accept government agricultural programming saying 'ngokweZANU lokhu' (that belongs to ZANU PF bigwigs and members). 92 The expanding politicisation of the supply of agricultural implements and grain was widespread by 2004, with repeated complaints from society and civil society organisations (CSOs) over recurring shortages in so-called opposition strongholds in rural areas and urban areas administered by opposition municipalities,93 while other equally dry and remote areas such as Mouth Darwin and Bindura, where the ruling ZANU PF dominated in elections, did not experience such shortages.94

The targeted shortages of grain against the opposition members were, however, not unexpected. In 2002, stressing the need to remove ZANU PF from power to bolster an economic turnaround, then MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai addressing a rally in the Midlands province remarked, 'Murikuti murikushaya chikafu, manje muchashaisisa' (you are saying you have no food; it will only get worse).95 He meant that with ZANU PF at the helm, the continued politicisation of food would leave millions in a perpetual state of hunger. During food distribution, the beneficiaries were selected by other villagers identifying eligible members whom they could confirm shared the same political affiliation.96 On the ground, in both urban and rural areas alike, constituencies belonging to key ZANU PF members of parliament were more frequently benefiting from different state-funded 'food-for-work' programmes such as Operation Migwagwa (road rehabilitation) facilitated by the GMB and the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ).97 Together, these institutions distributed grain seed preferentially to African families during exclusively ZANU PF functions, as captured in Figure 2 below.

In Mberengwa, for example, during the 2002/3 drought period, various cases were documented by different CSOs of so-called 'war veterans' and ZANU PF militia youths using aggressive tactics to prevent opposition supporters from participating in agricultural and food schemes funded by donors or buying maize grain from the GMB. Opposition supporters were publicly removed from food queues by the ZANU PF youth brigade militia in the presence of state security personnel, further revealing the power ZANU PF youths wielded in the communities.98 At the same time, it became increasingly common for local government politicians to divert international food aid and reward supporters, using the state-controlled GMB for such machinations.99 In areas such as Bulawayo and parts of Matabeleland South where locals continued to support the opposition, the GMB depots were constantly 'under rehabilitation ... no grain is available'.100 National machinery was being used to serve party interests benefiting a small segment of the population. It seemed that Tsvangirai's observations were correct. People were going to starve.

Nevertheless, ZANU PF stalwarts blamed urban and rural hunger on the failure of opposition leaders to spearhead agricultural developmental projects in their constituencies.101 Yet, when different food production initiatives were established, the same leaders were swift in bashing these as countering the government's efforts at archiving food security and community development. One such instance was how to mask the achievements of various opposition ventures such as the successful 'Harnessing Youth Potential' (HYP) project run by various MDC youths in Silozwi village in Matobo District.102 Critics swiftly shifted the conversation to accuse such programmes as being Western-sponsored initiatives with a 'regime change' agenda. Some argued that by advocating for alternative survival, food and crop diversification, the opposition was undermining the government's efforts to boost maize production and that this was really at the root of rural hunger. Moreover, they accused these programmes of operating through spreading falsehoods on the food situation in the country by selling small grains as opposed to maize to reflect an artificial food crisis in the country.103 Mugabe himself described such actions by community leaders as the 'Madhuku strategy of survival' premised on the peddling of 'falsehoods' to gain international donor sympathy and funding.104 Substituting small grains for maize across various districts where maize was previously popularly grown and strongly encouraged by the regime through costly agricultural mechanisation programmes easily became tantamount to treason, with small-grain farmers being perceived as opposing the national interest in striving towards reviving maize production that had suffered a slump since the FTLRP.

'Man-made' starvation?

By the end of 2005, widespread hunger was real. According to the WFP, about 6 074 000 people - almost half of the national population - were in dire need of food assistance.105 Recommendations by different agricultural experts were to harness the agricultural potential and rejuvenate existing institutions by promoting the cultivation of local drought-resistant crop varieties - primarily small grains.106 This would lighten the accumulating burden on the fiscus caused by over-investing in maize production and grain imports. Annually Zimbabwe required approximately 2.2 million tonnes of grain.107 According to statistics by the Agriculture Marketing Authority, this target could have been easily achieved for 2005 by combining maize and small grains marketed via the formal marketing boards, which included the GMB.108 Yet, in a counter-intuitive move, the Minister of Trade and Commerce in September 2005 sanctioned an export order on small grains to different breweries and millers based in Zambia to raise foreign currency for the GMB to import 150 000 tonnes of maize to meet domestic food requirements.109 Behind this action was the desire by the ZANU PF regime to strengthen political ties with various regional countries and generate sympathy over the Western-imposed sanctions on the regime, while to the West reflecting a robust commercial - export - sector despite the imposition of economic sanctions. At home, these moves were peddled to the populace as attempts at engagement with various developmental partners.

Yet under the surface rhetoric lay the opportunity to manipulate the flow of grain. Massive looting of resources and trade irregularities by selected agents in the grain industry worsened the state of food insecurity in the country. An independent UN human rights special rapporteur, Hilal Elver, observed that instead of crafting durable solutions to tackle food insecurity and improving efficiency in agriculture and food distribution, the government concentrated on maintaining its control of political power and facets of the economy as well as on wealth accumulation by top lieutenants.110 Zimbabwe was succumbing to artificially-manufactured starvation and 'most households in the country are unable to obtain enough food to meet their basic needs'.111 For example, in 2006 one of the country's major bread makers, Lobels Holdings, was acquired by David Chiweza, a retired military general with strong links with the ruling party.112 It would emerge later that, through this acquisition, cronies were able to syphon foreign currency into their personal accounts, while investments towards supporting grain production declined due to low capital injections under the new ownership.113 The most notable consequences for food security were a significant decline in wheat production, as shown in Table 1, culminating in a series of serious bread shortages.114 Yet difficulties in securing wheat moved families to use small grains innovatively to bake what some referred to as 'isimodo' (small-grains bread). For many, as our oral history research reveals, such alternatives became a welcome recurring feature in their lives to challenge their ongoing exclusion from access to food.115

So, while the entire grain sector suffered from underfinancing and misappropriation of funds, the brunt of this malfeasance was shouldered by small grain producers who shifted intuitively to relying on their personal networks for seeds, technical support as well as markets.116 Over the next coming years, eating small grains porridge and sadza became ever more popular across both rural and urban households, for both its economic attributes as well as the nutritional benefits associated with it.117 Its availability was advantaged by its improving performance in the dry climate that continued to rock the country.

'A last chance to vote right'

Seemingly unmoved by the crisis of deepening hunger, by late 2005 the ZANU PF regime continued to concentrate on the politics of safeguarding its status quo privileges.118 At the same time, in responses filled with frustration and desperation, some farmers took the initiative of their own volition to improve their domestic food security by creating cooperative units within their villages.119 Grain and input pool schemes, designed and run by the famers themselves, helped nascent agriculturalists to gain access to inputs like ploughs, fertilisers and seeds. For example, in 2006 in Gutu, the Chinyika Communities Development Project was established with the aim of addressing food shortages through facilitating the growth of more small-grain varieties among locals.120 Seeds were sourced from various places including South Africa - which had become the major lifeline to the hunger crisis in Zimbabwe - and distributed to households, while environmentally friendly, sustainable and efficient farming techniques and business concepts were taught on the sidelines to promote value addition to their small grains. Very few projects like this made an open display of wanting to circumvent partisan politics and focused instead on holistically improving the state of food security in the community. We discovered that similar initiatives operated by the ZANU PF Women's League in different wards in the Masvingo province, for instance, often failed because of the politics of patronage during decision-making and corrupt allocation of resources that stifled progress.121Moreover, poor management as a result of nepotism limited farmers' profits even after good small-grain harvests.122

Concomitantly, throughout the 2000s, the government continued to cite funding incapacity for its inability to support various small grains agricultural startups operated by youths from Matabeleland. Some interviewed disheartened youths in Lupane shared how many of their plans suffered 'stillbirth' after failing to garner adequate government support, and yet their ideas were aimed at not only providing food and a means of livelihood but also making effective use of idle lands.123 Rightly so, acknowledging this, a conflicted staffer within the Ministry of Youth spoke up about how vegetable gardens and small grains cultivation projects by the youth in areas across the arid Matabeleland South region would go a long way to improve household and ultimately national food security.124 Yet, conversations with youths across various spaces in the Matabeleland region revealed how there was an evergrowing sentiment of deliberate marginalisation and ostracization of resources by the state on young farmers from perceived opposition stronghold in the region. For some youths in the Matobo district, for example, complaints were rife over how most funds in the National Youth Fund were exhausted by other youth projects - mainly operated from Harare and the surrounding Mashonaland areas - long before reaching them. For example, a youth-planned agricultural fair had to be cancelled after the Ministry of Youth based in Gwanda failed to secure adequate funds to accommodate a high-level ministerial delegation's attendance.125

The communities' sense of state nepotism was reinforced when barely a few months later similar agricultural fairs were held successfully in Mount Darwin and Bindura, being well-publicised across local media outlets including the national broadcaster, Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation's ZTV.126 In another scenario, the government is pointed out as having stifled the growth of other small-grain agricultural projects by youth groups in Matobo including Sankonjana, Homestead and Bhalagwe through policy shifts and inconsistencies pertaining to the marketing and trading of grains. In particular, to be able to sell their small grains to large supermarkets, these young people were required to produce a registration and trading license. For those youths who were recognised as active ruling party members, exceptions were made. Others, using the name of the party (an act that was discouraged on paper, but openly and widely practised by junior and senior members alike), bulldozed their way into prime retail outlets. Using slogans such as 'tisu anhu acho' ('we are the people/ stockholders') they were able to control the flow of their grain. For non-party members, limited access to the lucrative markets, opportunities for raising the required funds to formalise their trading were thwarted. They were forced to sell their small grains to much smaller and informal local markets. On top of this, despite a visible growing interest in small grains not only in Matabeleland South but nationwide, farmers remained deprived of much profit because the commodity prices for small grains, unlike maize, remained low at the GMB.

In Masvingo, because of their kinship relations with senior government ministers and officials, several families in the district were granted agricultural inputs via the Presidential Input Scheme.127 Started in 2002, by mid-2006 this scheme had spent millions of dollars on seed and fertilisers, fuel and other agricultural merchandise. Yet once again this benefited selected farmers only - mostly those aligned to the ruling party.128 Some of these beneficiaries accumulated these benefits, only to sell them quickly to needy families excluded from the allocations instead of using them in agricultural production.129 One such beneficiary defended their actions saying, 'we need more than just grain...now I have money to buy other foodstuff I need'.130 With misused resources, little agricultural cultivation occurred and both household and national prospects of food security were jeopardised. The food crisis had become more than a need for food: it had developed a plight for basic survival. Widespread across the country by the late 2000s was a realisation that for survival, one had to (literally and metaphorically) cultivate and align oneself with the ruling party in order to evade hunger.

Criticising ZANU PF's partisan distribution of food and agricultural inputs, in November 2005, Tsvangirai noted how the best way to end the national food insecurity crisis was to do away with a heavy reliance on food hand-outs to rural families and instead develop an agricultural foundation to promote area-specific crops.131 He pointed out how farmer dependency was a growing problem, with farmers no longer showing the initiative to source their own inputs, and instead waiting inertly for government support. Added to this, the politicisation of state programmes coupled with the weak and ineffective administration in government, lead to distribution delays that in turn jeopardised national food security. In Mberengwa's Chamakudo-Mataga village, for instance, maize seed was being distributed at Chamakudo Primary School, the Mbuya Nehanda military camp and the Ngungubane military camp, renowned bases for youth terror groups that were pro-Mugabe.132 This acted as a deterrent to many farmers regardless of their political affiliation. Several organisations, including FAO, recommended that the state relocate essential departments such as the Ministry of Lands and Agriculture and the GMB to more neutral and safe areas in closer proximity to the farmers.133 Moreover, this would facilitate more regular contact between agricultural experts and farmers, greatly improving African agriculture in the communal areas. However, the state maintained these depots and made little attempt to increase the number of specialised service offices in certain areas. This witnessed a continued crosscutting insistence on maize even in those areas that repeatedly underperformed. For some grain farmers in the Mberengwa and Matobo districts, this gave them little confidence to expand their crop cultivation, fearing the burden of incurring heavy financial and agricultural losses from ecological factors as well as challenges in sourcing new markets on their own.134 Amid this, the severity of such challenges was admittedly softened by closer proximity to ZANU PF elites.

'There is no food crisis in Zimbabwe'135

By the mid-2000s, it had become apparent that a major obstacle towards securing food security in Africa was the growing use of populist political rhetoric to enforce agrarian development instead of harnessing scientific innovations.136 In Zimbabwe, by 2007 it was apparent that the country faced a grave food crisis.137 And yet, the government remained determined to promote the image of a flourishing nation in stark contrast to Western media depictions of the situation since the expulsion of most of the white farmers. Locally, in selling this rhetoric, ad hoc schemes such as the tepid National Basic Commodities Supply Enhancement Programme and Basic Commodities Supply Side Intervention (BACOSSI)138 programme were adopted. Concomitantly, on the global platform, multiple regional allies were engaged. For example, on 12 April 2008, South Africa's President Thabo Mbeki, on a SADC facilitated visit to Zimbabwe, announced, 'there is no crisis in Zimbabwe'.139 However, with persistent unpredictable and low rainfall from 2005, even with the heavy government investment in maize and wheat production - crops formerly grown by the ousted white farmers - yields remained disproportionately low considering the level of state investment as is evident in Table 1. For instance, some farmers targeted to produce about 10 000 tonnes of maize were barely achieving half that.140 However, even when maize yields were significantly lower than expected, the state labelled the talk of grain shortages as being malicious and targeted at 'demonizing the success of the FTLRP'.141 In June 2008, former Information Minister Jonathan Moyo remarked:

The war in Iraq was about oil, the war in Zimbabwe is about land and the country's detractors are using any means foul to get it... there is no food crisis in Zimbabwe...the lies are designed not to harm ZANU (PF), not harm the President, but Zimbabwe and Zimbabweans.it is foolish for anyone to expect 2.4 million tonnes of grains to be delivered to the GMB depots simply because the country harvested that figure . we know that the majority of people live in rural areas. They know that they are communal and A1 farmers and most of them kept their grain. Farmers bring their surplus to the GMB.142

But barely three months later the Minister of Agriculture, Joseph Made, admitted that the 'long-term benefits of the FTLRP were yet to kick in', and Zimbabwe was faced with grain deficits.143 Once again, as opposed to turning to local small grains stocks, the government was prompt to import maize from various countries including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Malawi and Zambia to address the looming food insecurity.144 Despite the financial burden this had on the national budget, ZANU PF persisted because it believed this reinforced regional trade relations and, more centrally, did not expose the poor agricultural performances of maize farmers that would be reflected with an open public shift to consumption of small grains.

By 2007, the state of the economy (and food security in particular) had declined further. Forecasted rains were unexpectedly low. Maize crops failed.145 In many parts of the country, agriculture had all but stagnated, surviving under the benevolence of state sponsorship through various loan and farm mechanisation schemes funded by the RBZ.146 By the end of 2007 just over 68 per cent of families nationwide that relied mainly on maize were left severely vulnerable to hunger, with the combined Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) report declaring that child hunger and malnutrition soared above 72 per cent of the population across most rural areas.147 During this period, many families turned to relying on imported mealie-meal and other basic commodities from neighbouring South Africa.148 However, although the poor rainfall patterns impacted widely across society, for some families the strain of food insecurity was lessened by private cultivation of small grains that fared well throughout the low rainfall periods between 2007 and 2009. In rural areas such as Polimagama in the Matobo District, for example, families even had surplus grain and took to supplying nearby major cities including Bulawayo and Gwanda.149 Without chorusing the need to grow small grains to combat hunger, state policy was slowly embracing the growth of small grains by local farmers. Small grains proved the most dependable during the turbulent 2000s, doubling their 1990s production mark by 2008. According to the Zimbabwe Agricultural Commodity Exchange, on 4 November 2007, the GMB held over 90 000 metric tonnes of small grains at the depots in Bulawayo, Gwanda and Lupane.150 This was enough to cater for the region's needs until the next major harvest in April the following year.

In addition, as Jan Vasina, Diana Wylie and John Iliffe have observed, during episodes of crisis, African families have found innovative - sometimes dangerous -ways to obtain food and survive.151 As food shortages worsened in 2007, the urban cultivation of small grains became ubiquitous in the water-scarce areas such as Bulawayo.152 Because of water challenges that riddled the region, small grains fields were gaining significant traction as opposed to maize. Successful small grain farmers managed to challenge food insecurity and also translate their agriculture into brisk business as the food crisis escalated. Various rural long-distance bus terminuses such as the Renkini and the Entumbane and Nkulumane ranks in Bulawayo's townships became hives of activity with farmers using these as centres to trade their grain with city dwellers. Bus terminals became the inexpensive stores where basic and (yet) hard to find commodities were accessible and this helped alleviate urban hunger. With small grains easing urban hunger, it became increasingly more difficult for politicians to leverage hunger into power through food handouts.153 For as long as the threat of starvation prevailed, the ruling ZANU PF was able to attract large numbers to attend its rallies - where food handouts, among other wares, were distributed.154These large crowds operated as an alibi, offering a statistical measurement of ZANU PF election victory and popularity across the county to reinforce the idea that sizable numbers voted for the party. Thus, efforts at rectifying the hunger problem were based on terms that maintained this status quo.

Conclusion

Food is political. The history of food (in)security in Zimbabwe is a story of state violence, corruption and inequality. Using the contested history of small grains in Zimbabwe from 2000 at the start of the contested FTLRP until the end of the decade in 2010, shortly after the Government of National Unity between ZANU PF and the two MDC factions, we showed how elites instrumentally used food to secure wealth and power by controlling food production, distribution and consumption in Zimbabwe.

Joining a growing body of historical literature on food security in postcolonial Africa and Zimbabwe in particular, this article shows how food insecurity was both purposeful and (sometimes) inadvertent, but was largely a result of the actions of the ruling ZANU PF government. We argue that the Mugabe regime used food insecurity both as a weapon and as an alibi for its hard-line domestic politics against regime change. We trace how the expulsion of white commercial farmers coupled with erratic rainfall patterns and poor policing, triggered a wave of poor agricultural seasons and a series of food shortages. We underline that the development of food security over the decade was exacerbated by a deepening economic crisis and increasing political instability. Drought and food shortages became rife, and with the unequal distribution of food aid and agricultural aid, the state was able to augment its power through regulating and controlling the key apparatus in food production and distribution, namely the Grain Marketing Board and Reserve Bank, during this period. Occasionally, select communities, ruling party cadres and, almost always, top ZANU PF elites were able to appropriate government aid for themselves. Added to political agitation, these glaring disparities fuelled social protest, triggering citizen resistance manifested in some cases through food riots155 and subaltern initiatives such as a growing reliance on the informal traders and more formal initiatives like food imports to combat hunger. An anthropogenic 'hunger' effectively prolonged ZANU PF's dominance over society.

We also show how the Mugabe regime over-invested in the development of maize and other formerly white agricultural sectors, in a strained attempt to counter Western perceptions that since the FTLRP, Zimbabwean agriculture and society had declined. In the process, it was able to control and, in many instances, crush rising opposition voices. In times of hunger, the government prioritised feeding its loyal constituencies with maize. Yet between 2005 and 2008 it advised other constituencies to turn to the less expensive small grains for their food security - an aspect that (ironically for the Mugabe regime) proved very beneficial in the long run as maize increasingly underperformed agriculturally. Furthermore, we show that by 2008 hunger was a weapon used in political campaigning. Yet, notwithstanding the widespread politicisation of food, we were able to observe how this triggered the growth of the dissident small grains - a form of literal 'under-ground', 'grass-roots' resistance.

REFERENCES

'Small Grains are Tough to Sell in Zimbabwe'. Accessed 7 October 2020. http://Carbon-Based-Ghg.Blogspot.Com/2012/05/Small-Grains-Are-Tough-Sell-In-Zimbabwe.Html. [ Links ]

'Hungry Zim People Grab Food in New Riot'. Accessed 21 September 2020. https://www.iol.co.za/news/africa/hungry-zim-people-grab-food-in-new-riot-50779. [ Links ]

'Small Grains are Tough Sell'. Accessed 6 October 2020. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/Report/95489/Zimbabwe-Small-Grains-Are-Tough-Sell. [ Links ]

'Famine Becomes Mugabe Weapon'. Accessed 30 September 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/World/2002/Nov/10/Zimbabwe.Famine. [ Links ]

'Mugabe Describing the Lovemore Madhuku Strategy of Survival'. Accessed 21 May 2021. https://youtu.be/5Mq0cVE7AmU. [ Links ]

'Mugabe vs Tsvangirai in Violent Zimbabwe Elections (2002)'. Accessed 6 October 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ws3NaEQIA2o. [ Links ]

'Small Grains Hold Promise for Alleviating Food Insecurity in Zimbabwe'. Accessed 20 October 2020. https://Globalpressjournal.Com/Africa/Zimbabwe/Small-Grains-Hold-Promise-Alleviating-Food-Insecurity-Zimbabwe/. [ Links ]

Alexander, J and J. McGregor. 'Introduction: Politics, Patronage and Violence in Zimbabwe'. Journal of Southern African Studies, 39, 4 (2013), 749-763. [ Links ]

Alexander, J. The Unsettled Land: State-Making and the Politics of Land in Zimbabwe, 1893-1903. London: James Currey Publishers, 2006. [ Links ]

Aliber, M. and B. Cousins. 'Livelihoods after Land Reform in South Africa'. Journal of Agrarian Change, 13, 1 (2012), 140-165. [ Links ]

Aljazeera. 'Zimbabwe's Aid Dependence Growing'. Accessed 13 October 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/News/2009/2/7/Zimbabwe-Aid-Dependence-Growing. [ Links ]

Baro, M. and T.F. Denbel. 'Persistent Hunger: Perspectives on Vulnerability, Famine and Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa'. Annual Review of Anthropology, 35, (2006), 521-538. [ Links ]

Baudron, F., R. Nazare, and D. Matangi. 'The Role of Mechanization in Transformation of Smallholder Agriculture in Southern African: Experience from Zimbabwe', in Transforming Agriculture in Southern Africa edited by R.A. Sikora, E.R. Terry, P.L.G. Vlek and J. Chitya, 52-60. London: Routledge, 2020. [ Links ]

Bayart, J.F. The State in Africa: The Politics of the Belly. London: Longman, 1993. [ Links ]

Bernard, S., M. Fordham, and A. Collins. 'Disaster Resilience and Children: Managing Food Security in Zimbabwe's Binga District'. Children, Youth and Environments, 8, 1 (2008), 303-331. [ Links ]

Bhatasara, S., 'Women, Land and Poverty in Zimbabwe: Deconstructing the Impacts of the FTLRP'. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 13, 1 (2011), 316-330. [ Links ]

Brown, D. 'Climate Change Impacts, Vulnerability and Adaptation in Zimbabwe'. IIED Climate Change Working Paper Series, 3 (2012), 1-40. [ Links ]

Cavanagh, C. 'Entitlement Removal and State Induced Famine in Zimbabwe'. Sojourners, 1 (2009), 1-16. [ Links ]

Chanza, N. and V. Gundu-Jakarasi. 'Deciphering the Climate Change Conundrum in Zimbabwe: An Exposition', in Global Warming and Climate Change, edited by J.P. Tiefenbacher, 1-25. London: Intechopen, 2020. [ Links ]

Chingono, M. 'Food Aid, Village Politics and Conflict in Rural Zimbabwe'. Accessed 29 September 2020. http://www.Accord.Org.Za/Conflict-Trends/Food-Aid-Village-Politics-And-Conflict-In-Rural-Zimbabwe. [ Links ]

Cliffe, L., J. Alexander, B. Cousins and R. Gaidzanwa. 'An Overview of the Fast Track Land Reform in Zimbabwe: Editorial Introduction', in Outcomes of the Post-2000 Fast Track Land Reform in Zimbabwe, edited by L. Cliffe, J. Alexander, B. Cousins and R. Gaidzanwa, 6-9. London: Routledge, 2013. [ Links ]

Degeorges, A. and B. Reilly. 'Politicization of Land Reform in Zimbabwe: Impacts on Wildlife, Food Production and the Economy'. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 64, 5 (2007), 571-586. [ Links ]

Eriksen, S.S. 'State Formation and the Politics of Regional Survival: Zimbabwe in Theoretical Perspective'. Journal of Historical Sociology, 23, 2 (2010), 316-340. [ Links ]

Falola, T. The Power of African Cultures. Rochester: University of Rochester Press 2003. [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organization, Food Assessment Report: FAO Crop and Food Security Assessment Mission to Southern Africa, 2001. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2001. [ Links ]

Giampietro, M. 'Food Security in Africa: A Complex Issue Requiring New Approaches to Scientific Evidence and Quantitative Analysis', in Transforming Agriculture in Southern Africa: Constraints, Technologies, Policies and Processes, edited by R.A. Sikora, E.R. Terry, P.L.G. Vlek and J. Chitya, 298-307. London: Routledge, 2020. [ Links ]

Good, K. 'Dealing with Despotism: The People and the Presidents', in Zimbabwe's Presidential Election 2002: Evidence, Lessons and Implications, edited by H. Melber, 7-30. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2002. [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch, 'Not Eligible: The Politicization of Food in Zimbabwe'. Human Rights Watch, 15, 17 (2003), 1-35. [ Links ]

Iliffe, J. 'Famine in Zimbabwe, 1890-1960'. University of Zimbabwe History Department Seminar Paper 70, (1987), 1-10. [ Links ]

Iliffe, J. The African Poor: A History. London: Cambridge University Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Jayne, T.S., M. Chisvo, M. Rukuni and P. Masanganise, 'Zimbabwe's Food Security Paradox', in Zimbabwe's Agricultural Revolution Revisited, edited by M. Rukuni, P. Tawonezvi and C. Eicher, 525-541. Harare: University of Zimbabwe Publishers, 2006. [ Links ]

Kangira, J. 'A Study of the Rhetoric of the 2002 Presidential Election Campaign in Zimbabwe'. PhD Thesis, University of Cape Town, 2005. [ Links ]

Kauma, B. 'A Socio-Economic History of Matobo District in Zimbabwe, 1980-2015'. MA dissertation, University of Zimbabwe, 2016. [ Links ]

Kauma, B. and S. Swart. '''Many of the dishes are no longer eaten by sophisticated urban Africans". A Social History of Eating Small Grains in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) c. 1920s to the 1950s'. Revue d'Histoire Contemporaine de l'Afrique, 2 (2021), 86-111. [ Links ]

Kusena, B. 'Coping with New Challenges: The Case of Food Shortage Affecting Displaced Villagers Following Diamond Mining Activity at Chiadzwa, Zimbabwe, 2006-2013'. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 17, 2 (2015), 14-24. [ Links ]

Machingaidze, V. 'The Development of Settler Capitalist Agriculture in Southern Rhodesia with Reference to the Role of the State'. PhD Thesis, University of London, 1980. [ Links ]

Madimu, T. 'Food Imports, Hunger and State Making in Zimbabwe, 2000-2009'. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 55, 1, (2020), 128-144. [ Links ]

Madimu, G. 'Zimbabwe Food Security Issues Paper'. Forum for Food Security in Southern Africa. 1-52. [ Links ]

Masanganise, P. 'Marketing Agricultural Commodities through the Zimbabwe Agricultural Commodity Exchange', Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2019. Accessed 25 August 2019. https://library.fes.de/fulltext/bueros/simbabwe/01176.htm. [ Links ]

Mazzeo, J. 'The Double Threat of HIV/AIDS and Drought on Rural Household Food Security in Southeastern Zimbabwe'. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 35, 1 (2011), 167-186. [ Links ]

Mkodzongi, G. and P. Lawrence. 'The Fast-Track Land Reform and Agrarian Change in Zimbabwe'. Review of African Political Economy, 46, 159 (2019), 1-13. [ Links ]

Mlambo, A. and E. Pangeti. The Political Economy of the Sugar Industry in Zimbabwe, 1920-1990. Harare: University of Zimbabwe Publications, 1996. [ Links ]

Morin, K. 'Differentiating Between Food Security and Insecurity'. The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 39, 6 (2014), 381-402. [ Links ]

Moyo, S., W. Chambati, T. Murisa, D. Siziba, C. Dangwa, K. Mujeyi and N. Nyoni. FastTrack Land Reform Baseline Survey in Zimbabwe, Trends and Tendencies, 2005/6. Harare: African Institute for Agrarian Studies, 2009. [ Links ]

Moyo, S. and P. Yeros. Reclaiming the Land: The Resurgence of Moral Movements in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. London: Zed Books, 2005. [ Links ]

Moyo, S. and W. Chambati. Land and Agrarian Reform in Zimbabwe: Beyond White Settler-Capitalism. Dakar: Codesria, 2013. [ Links ]

Moyo, S. 'Changing Agrarian Relations after Redistributive Land Reform in Zimbabwe'. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38, 5 (2011), 939-966. [ Links ]

Moyo, S. 'Regime Survival Strategies in Zimbabwe in the 21st Century'. Journal of Sociology and Social Work, 2, 1 (2014), 21-49. [ Links ]

Muchineripi, P. Feeding Five Thousand: The Case for Indigenous Crops in Zimbabwe. London: Africa Research Institute, 2008. [ Links ]

Mukarumbwa P. and A. Mushunje. 'Potential of Sorghum and Finger Millet to Enhance Household Food Security in Zimbabwe's Semi-Arid Regions: A Review'. Paper presented at the 8th Conference of the African Association of Agricultural Economists at Cape Town (16-19 September 2010), 1-23. [ Links ]

Murwira, K., H. Wedgwood, C. Watson, E. Win and C Tawney. Beating Hunger: The ChiviExperience. London: Intermediate Technology Publications, 2000. [ Links ]

Musemwa, M. 'Disciplining a "Dissident" City: Hydropolitics in the City of Bulawayo, Matabeleland Zimbabwe, 1980-1994'. Journal of Southern African Studies, 32, 2 (2006), 239-254. [ Links ]

Musvota, C. and R.M. Mukonza. 'An Analysis of Corruption in the Grain Marketing Board, Zimbabwe'. Journal of Public Administration, 56, 3 (2011), 474-487. [ Links ]

Nkomo, L. 'Chiefs and Government in Postcolonial Zimbabwe: The Case of Makoni District, 1980-2014'. MA dissertation, University of the Free State, 2015. [ Links ]

Phiri, K., T. Dube, P. Moyo, C. Ncube and S. Ndlovu. 'Small Grains "Resistance": Making Sense of Zimbabwean Small Holder Farmer Cropping Choices and Patterns within a Climate Change Context'. Cogent Social Sciences, 5 (2019), 1-13. [ Links ]

Pilossof, R. The Unbearable Whiteness of Being: Farmers' Voices from Zimbabwe. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press, 2012. [ Links ]

Raftopoulos, B. and A. Mlambo. 'Outside the Third Chimurenga: The Challenge of Writing a National History of Zimbabwe'. Critical African Studies, 4, 6 (2011), 2-14. [ Links ]

Raftopoulos, B. and A. Mlambo. 'The Hard Road to Becoming National', in Becoming Zimbabwe: A History from the Pre-colonial Period to 2008, edited by B. Raftopoulos and A. Mlambo, xvii-xxxiv. Harare: Weaver Press, 2008. [ Links ]

Sachikonye, L. The Situation of Commercial Farm Workers after Land Reform in Zimbabwe: Report Prepared for the Farm Community Trust of Zimbabwe. London: CIIR, 2003. [ Links ]

Sachikonye, L. Zimbabwe's Lost Decade: Politics, Development and Society. Harare: Weaver Press, 2011. [ Links ]

Scoones, I. Sustainable Livelihoods and Rural Development. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2015. [ Links ]

Selby, A. 'Commercial Farmers and the State: Interest Group Politics and Land Reform in Zimbabwe'. PhD Thesis, University of Oxford, 2006. [ Links ]

Sen, A. 'The Food Problem: Theory and Policy'. Third World Quarterly, 4, 3, (1982), 447-459. [ Links ]

Takuva, T. 'A Social, Environmental and Political History of Drought in Zimbabwe, 1911-1992'. PhD Thesis, Stellenbosch University, 2022. [ Links ]

Tawodzera, G., L. Zanamwe, and J. Crush. The State of Food Insecurity in Harare, Zimbabwe, Urban Food Security Series No. 13. Kingston and Cape Town: Queen's University and AFSUN, 2012. [ Links ]

UN News Global Perspective Human Stories. 'Zimbabwe facing man-made starvation, says UN expert'. Accessed 21 September 2020. https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/11/1052411. [ Links ]

Vansina, J. 'Finding Food and the History of Precolonial Equatorial Africa: A Plea'. African Economic History, 7 (1979), 9-20. [ Links ]

Vaughan, M. 'Famine Analysis and Family Relations: 1949 in Nyasaland'. Past and Present (1985), 177-205. [ Links ]

Whitehead, A. "'I'm Hungry, Mum": The Politics of Domestic Budgeting', in Of Marriage and Market, edited by K. Young, et al. London: CSE Books, 1984, 88-111. [ Links ]

World Food Programme (WFP), 'State of Food Insecurity and Vulnerability in Southern Africa: Regional Synthesis - November 2006', National Vulnerability Assessment Committee Reports. Gaborone: WFP, 2006. [ Links ]

Wylie, D. Starving on a Full Stomach: Hunger and the Triumph of Cultural Racism in Modern South Africa. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 2001. [ Links ]

* We thank Dr Godfrey Hove, Prof Meredith McKittrick and Prof Alois Mlambo and the History Friday Mornings Research Group, Stellenbosch University.

1 'Zimbabwe facing man-made starvation, says UN expert', News Global Perspective Human Stories, accessed 21 September 2020, https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/11/1052411.

2 A. Sen, 'The Food Problem: Theory and Policy', Third World Quarterly, 4, 3 (1982), 447-459.

3 According to the World Food Programme, in 2019, about 5.5 million people are vulnerable to starvation - this is almost half the nation's population based on Zimstat census records that note the current population as 13.2 million.

4 There is a distinction between 'food insecurity' and 'hunger'. Hunger may represent the absence of food, but food security is a much more encompassing term, denoting a situation when people, at all times, have access to sufficient and nutritious food. See Food and Agriculture Organization, Food Assessment Report: 'FAO Crop and Food Security Assessment Mission to Southern Africa, 2001' (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2001), 23-26.

5 B. Raftopoulos and A. Mlambo, 'Outside the Third Chimurenga: The Challenge of Writing a National History of Zimbabwe', Critical African Studies, 4, 6 (2011), 2-14.

6 By mid-2005, media practitioners in Zimbabwe had become heavily polarised, with state outlets which included The Herald and The Chronicle being pro-ZANU PF in their broadcasting. Alternative media narratives were carried by newspapers such as The Standard, The Daily News and Newsday, and as we shall demonstrate, these alternative voices were heavily stifled by the ZANU PF government.

7 L. Sachikonye, Zimbabwe's Lost Decade: Politics, Development and Society (Harare: Weaver Press, 2011).

8 V. Machingaidze, 'The Development of Settler Capitalist Agriculture in Southern Rhodesia with Reference to the Role of the State' (PhD Thesis, University of London, 1980), 417. Also see A. Mlambo and E. Pangeti, The Political Economy of the Sugar Industry in Zimbabwe, 1920-1990 (Harare: University of Zimbabwe Publications, 1996).

9 Sen, 'The Food Problem', 447.

10 T. Madimu, 'Food Imports, Hunger and State Making in Zimbabwe, 2000-2009', Journal of Asian and African Studies, 55, 1 (2020), 128-144.

11 M. Baro and T.F. Denbel, 'Persistent Hunger: Perspectives on Vulnerability, Famine and Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa', Annual Review of Anthropology, 35 (2006), 521-538.

12 N. Chanza and V. Gundu-Jakarasi, 'Deciphering the Climate Change Conundrum in Zimbabwe: An Exposition', in J.P. Tiefenbacher (ed.), Global Warming and Climate Change (London: Intechopen, 2020), 1-25; and D. Brown, 'Climate Change Impacts, Vulnerability and Adaptation in Zimbabwe', IIED Climate Change Working Paper Series 3 (2012), 1-40.

13 A. Degeorges and B. Reilly, 'Politicization of Land Reform in Zimbabwe: Impacts on Wildlife, Food Production and the Economy', International Journal of Environmental Studies, 64, 5 (2007), 571-586.

14 G. Madimu, Zimbabwe Food Security Issues Paper (Forum for Food Security in Southern Africa), 1-52.

15 G. Tawodzera, L. Zanamwe and J. Crush, The State of Food Insecurity in Harare, Zimbabwe: Urban Food Security Series No. 13 (Kingston and Cape Town: Queen's University Press and AFSUN, 2012).

16 Zimbabwe's Agricultural Revolution Revisited, eds M. Rukuni, P. Tawonezvi and C. Eicher (Harare: University of Zimbabwe Publishers, 2006)

17 A. Whitehead, ''I'm Hungry, Mum: The Politics of Domestic Budgeting', in Of Marriage and Market, eds K. Young, C. Wolkowitz and R. McCullagh (London: CSE Books, 1984), 34.

18 World Food Programme (WFP), 'State of Food Insecurity and Vulnerability in Southern Africa: Regional Synthesis, November 2006', National Vulnerability Assessment Committee Reports (2006), 3-4.

19 T.S. Jayne, M. Chisvo, M. Rukuni and P. Masanganise, 'Zimbabwe's Food Security Paradox', in Zimbabwe's Agricultural Revolution Revisited, 525-541.

20 K. Morin, 'Differentiating Between Food Security and Insecurity', The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 39, 6 (2014), 381. Measured periods include between harvest or between one wage until the next in wage-earning communities.

21 J. Iliffe, 'Famine in Zimbabwe, 1890-1960', University of Zimbabwe History Department Seminar Paper 70 (1987), 4-5.

22 T. Takuva, 'A Social, Environmental and Political History of Drought in Zimbabwe, 1911-1992' (PhD Thesis, Stellenbosch University, 2022).

23 M. Vaughan, 'Famine Analysis and Family Relations: 1949 in Nyasaland', Past and Present (1985), 177-205.

24 J. F. Bayart, The State in Africa: The Politics of the Belly (London, Longman, 1993). 'Politics of the belly' is a phrase that suggests the necessities of survival by securing food, motivating different social and political decisions among communities.

25 J. Alexander and J. McGregor, 'Introduction: Politics, Patronage and Violence in Zimbabwe', Journal of Southern African Studies, 39, 4 (2013), 749-763.