Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Historia

On-line version ISSN 2309-8392

Print version ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.65 n.1 Durban May. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8392/2020/v65n1a4

Cannabis policing in mid-twentieth century South Africa

Phumla Innocent NkosiI; Richard DeveyII; Thembisa WaetjenIII

IGraduated with an MA in History from the University of Johannesburg in 2020

IIDirector of the Statistical Consultation Service, University of Johannesburg

IIIAssociate professor of History at the University of Johannesburg. Corresponding author: twaetjen@uj.ac.za

ABSTRACT

From 1922, cannabis was policed in South Africa as a "dangerous drug". At mid-century, the United Nations recorded South African cannabis seizures as accounting for more than half of the world's annual recorded totals. This article outlines some main trends in South African cannabis policing between the late 1920s and 1970. It uses quantitative data derived from historical police records to document the impact of a shift in policing strategy - from a focus on possession to a directed targeting of supply - following recommendations made in a 1952 governmental report. Analysis demonstrates how this policy change, along with other factors, impacted arrests and amounts of cannabis seized, by division and district. We situate statistical findings within South Africa's political landscape.

Keywords: Cannabis; dagga; drug control, race segregation; policing; SouthAfrica.

OPSOMMING

Cannabis is sedert 1922 as 'n "gevaarlike dwelmiddel" in Suid-Afrika beheer. Teen die middel van die eeu het die Verenigde Nasies vermeld dat die Suid-Afrikaanse beslagleggings op cannabis verantwoordelik was vir meer as die helfte van die wereld se jaarlikse totaal. Hierdie artikel skets die hooftendense van die Suid-Afrikaanse polisiëring van cannabis vanaf die laat 1920's tot 1970. Dit maak gebruik van kwantitatiewe data afkomstig van historiese polisiestukke ten einde die impak na te gaan van 'n verandering - 'n fokus op besit na die doelgerigte teiken van voorsiening - in die polisie se strategie wat gevolg het op die aanbevelings van 'n regeringsverslag in 1952. Die analise wys op die impak wat hierdie beleidsverandering, naas ander faktore, gehad het op arrestasies en die hoeveelhede cannabis wat gekonfiskeer is, volgens afdeling en distrik. Ons situeer die statistiese bevindinge in die Suid-Afrikaanse politieke landskap.

Sleutelwoorde: Cannabis; dagga; dwelmbeheer; rasseskeiding; polisiëring, Suid-Afrika.

Introduction

In 2018, the Constitutional Court of South Africa declared that the personal possession, use and cultivation of a limited amount of cannabis - known locally as "dagga" - fell within the right to privacy protocols of Section 14 of the Bill of Rights. This confirmed the findings by the Cape High Court the previous year, and overturned existing drug legislation.1 The ruling challenged a prohibition dating from 1922. In the years since these court rulings, official attitudes to cannabis have begun to align with liberalising policy reforms in other nations, and with the commercial opportunities they represent. In February of 2020, for example, Gauteng province premier David Makhura announced that a domestic agro-industry in medicinal cannabis would become a pillar of economic development for the region.2

This recent shift of governmental approaches to cannabis could not be more dramatic. For almost a century, cannabis was policed in South Africa as a "dangerous drug". A 1922 Customs and Excise Amendment fixed, as a criminal intoxicant, dagga's previously more open political and ontological status.3 Moreover, applications by Prime Minister J.C. Smuts's office to the League of Nations influenced the criminalisation of cannabis in international law where, in 1925, it joined opium, cocaine and morphine as a restricted substance.4 In 1928, the South African cannabis legislation was transferred to the dominion colony's first national Medical, Dental and Pharmacy Act. Under Section 61 of the law, no unlicensed person was allowed to:

... import, convey, transmit, export, tranship, cultivate or collect, or assist in the importation, conveyance, transmission, exportation, transhipment, cultivation or collection of any plant or portion of a plant from which any habit-forming drug can be manufactured; or administer, give, sell, barter, exchange or otherwise supply or use, accept, purchase, take in exchange or otherwise receive or be in possession of any such drug, plant or portion of a plant.5

Convicted offenders were liable to a fine of up to £100, a term of imprisonment not exceeding six months, or both.6 Under Section 69, pipes, receptacles and appliances for the purpose of smoking a habit-forming drug were also regulated.

Amendments in 1955 increased fines (to £500) as well as recommended prison terms (to 12 months). Otherwise, legislation related to cannabis saw little substantive change until 1971, with the draconian Abuse of Dependency-Producing Substances and Rehabilitation Centres Act.7 Yet, in the mid-century period, changes in policing strategies transformed the landscape of South Africa's cannabis control.

In this article, we track these changes. We provide a picture of national cannabis policing, from prohibition in 1922 to the late 1960s. More specifically, using quantitative data derived from district and divisional police reports from 1932 to 1960, we show national and divisional trends in cannabis arrests and amounts seized. We provide a historical context for understanding change over time, most importantly the shift to a supply-side approach to cannabis control.

When viewed in relation to global developments concerning cannabis policy, the South African case is noteworthy. In 1953, the eighth session of the United Nations (UN) Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) addressed "The Problem of Indian Hemp". The report included a table of annual data furnished by 46 governments in accordance with article 21 of the 1931 Convention. It showed seizures of "Indian Hemp, its resins and preparations made from it", measured in kilograms, for the years 1946 to 1951.8 There are some obvious problems with the data in this report (see Note A at the end of the article, headed "Notes on the statistical methods used for this article"). Nonetheless, the commission's report demonstrated two realities about South Africa: a comparatively robust cannabis economy and an energetic commitment to policing.

Indeed, for the years in which South African figures are indicated, they show a rise in local seizure amounts far beyond any other reporting state, accounting for more than half of the global totals calculated for each year represented: 50 per cent in 1946, 52 per cent in 1948, 67 per cent in 1950 and 76 per cent in 1951.9 Inserting cannabis seizure data from the local police records we use below (translated into kilograms) for the two missing years, shows South Africa's proportion of global seizures as 57 per cent in 1947 and 62 per cent in 1949, confirming the two overall patterns indicated by the UN report: rising numbers of national quantities seized, and these amounts as a significant proportion of global reported totals.

The data in this window period suggest a shift taking place in South Africa, which is also confirmed in the more comprehensive local statistics we use. The most important finding to be explained is a transformation in the nature and scope of policing from the late 1940s and early 1950s. We show how this constituted a shift from the focus on arrests for possession, to a targeting of cannabis cultivators and large-scale suppliers. The section below summarises the trends found in the statistics. In later sections, we explain these trends by providing a context for understanding changes in policing and cannabis control, and for making sense of the concerted push for new approaches under the National Party apartheid state.

What mid-century police statistics reveal

Police statistics help to document a mid-century shift in cannabis policing strategies towards targeting supply. From 1932 to I960, in compliance with article 21 of the 1931 League of Nations Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the Department of Police of the South African government collated annual reports enumerating arrests and quantities (in lbs) of cannabis seized from each police division, with tallies also for each reporting district within divisions.10 Statistics processed from the raw documents provide information about cannabis policing across time and space, revealing some notable trends (see Note Β at the end of this article: "Notes on the statistical methods used in this article").

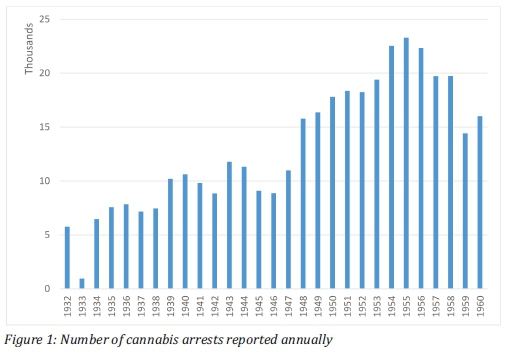

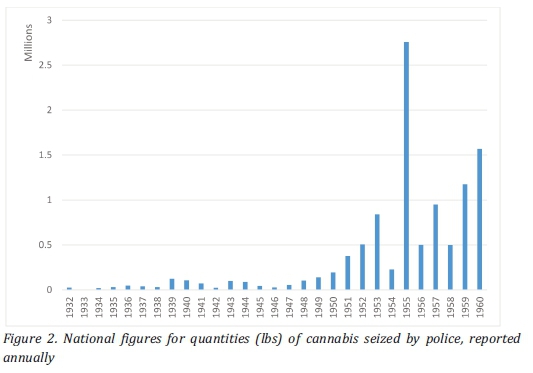

In these decades, increases in the national annual tally of both cannabis arrests and seizures are apparent. These are shown in Figures 1 and 2 respectively. Figure 1 shows the number of arrests reported each year in thousands. In 1932, across all divisions, the police reported 5 762 arrests and into the 1940s the average annual figures doubled. A sharper rise is visible in 1948, after which the number of arrests fluctuated between 15 and 20 thousand, peaking in 1955 at as many as 23 289 arrests. We know from other national data that a general rise in the number of cannabis arrests continued unabated into the late 1960s. The 1970 Grobler Commission report, for example, shows that in 1967 and 1968, cannabis-related arrests were in the low 30 thousands.11

Annual figures for quantities of cannabis seized (Figure 2) also document an increase over this period.12 In contrast to the steadier rise shown for arrest figures, the seizures data indicates a spike beginning in the late 1940s. Between 1932 and 1950, the annual average of dagga confiscated across the Union was 67 249 lbs. From 1951 until I960, the average annual amount seized was 929 916 lbs. The first report in 1932 gave a sum of 26 564 lbs. There is a small but visible peak in 1939 (124 768 lbs), and subsequent fluctuation until 1949, when the amounts begin to rise dramatically.

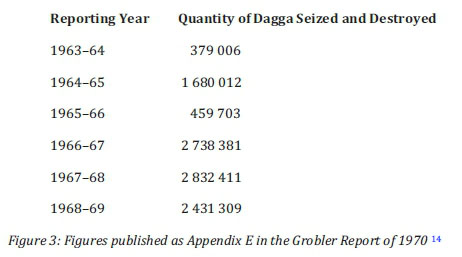

A clear outlier year in the seizure data is 1955. Of the 2 757 962 lbs recorded, 89 per cent was attributed to seizures within a single district - Nelspruit, in the Transvaal police division. Our investigation of other South African Police files affirms that officials replicated this same high figure in subsequent documentation, suggesting that contemporaries accepted it as factual (refer to Note C at the end of this paper under the heading "The statistical methods used for this article"). Other data, compiled through reporting protocols adopted from 1963, show that into the 1960s the national figures of confiscated cannabis routinely surpassed 2 million pounds (Figure 3).13 But we have not found a breakdown of those figures by districts for these later years and therefore cannot assess the comparative probabilities of the 1955 Nelspruit case. Even calculated without the 1955 Nelspruit report, however, the statistics confirm a sharp rise in amounts of cannabis seized from the century's mid-point.

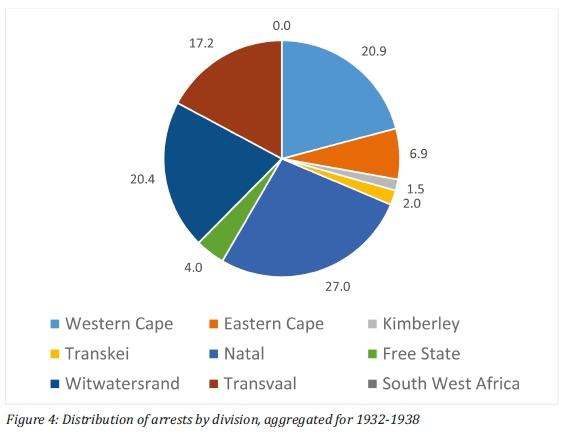

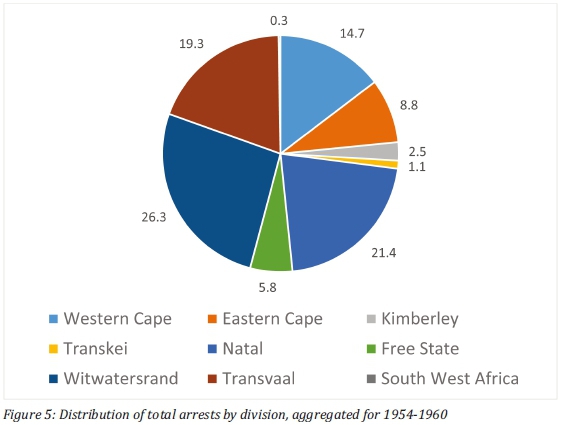

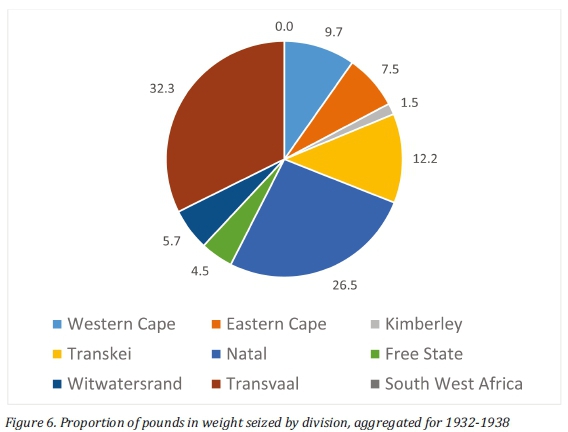

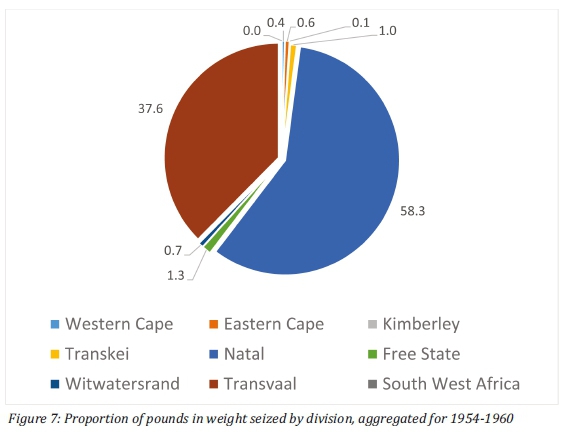

Further evidence documenting a shift, this time showing geographical location, becomes evident when distribution of arrests and seizures in the different policing divisions are compared across time. Figures 4 to 7 show aggregated sums of arrests and seizures, by each police division, across two seven-year periods (i.e., one snapshot for the early 1930s (1932-1938) and the other ofthe latter 1950s (from 1954 to 1960).

Figures 4 and 5 show the divisional distribution of recorded arrests for these respective periods to be relatively stable over time. However, some minor changes can be noted. There was a decrease in the proportion of arrests for the Western Cape (from 20,9 per cent to 14,7 per cent) and also for Natal (27,0 per cent to 21,4 per cent). A rise is evident for the Witwatersrand division (20,4 per cent to 26,3 per cent), with smaller increases showing for the Eastern Cape and Transvaal. On the other hand, changes in divisional distributions of cannabis seizures, for these same two periods confirm a picture of dramatic change (see Figures 6 and 7).

Figures 6 and 7 portray a shift in the geographical distribution of the national total quantity of cannabis confiscated by police. In the 1930s, the distribution for quantities of seized cannabis were analogous to distributions of arrests, although Natal, the Transkei and the Transvaal showed slightly higher proportions of seized cannabis relative to their contribution to arrests (Figure 6). In the 1950s, however, a full 96,0 per cent of cannabis seized in the Union came from two divisions only: Natal (accounting for more than half, or 58,3 per cent) and the Transvaal (37,0 per cent). It is evident that these two regions account for the greater quantities of seized cannabis in the 1950s.

Taken as a ratio in each division, reported arrests and quantities of cannabis seized suggest the nature of cannabis crimes being policed within its geography. In the late 1950s, the amount of cannabis confiscated in the metropolitan Witwatersrand district - the centre of industrial gold-mining - accounted for less than 1 per cent of the total amount of cannabis seized nation-wide (see Figure 7) but over a quarter of cannabis arrests (Figure 5). A ratio of high arrests and small quantity suggests the policing of dagga possession or small-time trade.

By contrast, Natal and Transvaal, for the same period, show lower arrest figures and large-scale seizures, suggestive of a target on supply. The largely rural Transvaal division accounted for 40 per cent of national seizures (Figure 7) but less than 20 per cent of arrests (Figure 5).

When we break down the Transvaal figures by district for 1931-1960, we see that the Nelspruit district accounted for 72,8 per cent of all cannabis confiscated in this division, with Middelburg next in line at 13,0 per cent. Newspaper sources confirm these districts as geographically proximate to large-scale cannabis cultivation which attracted police action. For example, on 18 February 1953, the Rand Daily Mail reported on "SA's Biggest Dagga Raid" to date, where 50 tons of cannabis plants -representing a retail amount estimated at £192 000 - was destroyed during a 10-day police action in the territory between Lydenburg and Olifants River in the Eastern Transvaal. These districts were also within or adjacent to transnational routes, with cannabis moving into South Africa from Swaziland and Mozambique. Like the Transvaal, Natal showed dagga seizures concentrated in districts proximate to dagga growing and transport routes. Vryheid police seizures account for 28 per cent within the division and Dundee district almost 26 per cent.

Beyond the notable rise in mid-century, we can see, from Figure 2, the presence of smaller spikes in cannabis seizures. In the short periods 1939 to 1940, and 1943 to 1944, the main districts (as defined by total pounds seized over the two-year period) were also located in the Transvaal and Natal.15 The data suggests that police attention to crop-growing districts, and those located on transport routes during these years, account for the rise in seizures.

Statistical data from police reports show a pattern of urban arrests for possession and small-time dealing until the late 1940s, though with some serial attention given to rural policing in geographies of cannabis transport and cultivation. It documents a continued emphasis on urban arrests and on possession but with a shift towards the policing of supply into the 1950s and 1960s that made an enormous difference in seizure quantities. In the next sections, we analyse these trends in a historical account and consider their significance within the context of South African policing and cannabis politics.

Cannabis policing in context

Cannabis was a part of long-standing indigenous practices in much of southern Africa, and it had varied uses and meanings, including as a trade item.16 Its cultivation was largely in hospitable south-eastern climatic zones, where African women traditionally presided over plant production. While cannabis was an ingredient in some of the patent medicines used by English-speaking settlers, most of that population brought little general knowledge of this plant to South Africa. By contrast, Dutch-speaking trekboers, who incorporated elements of African medicines into their home remedies, adopted some local knowledge and practice.17 As David Gordon shows, Cape farmers also used cannabis (like liquor and tobacco) in strategies for recruiting and exploiting local labour.18 Cannabis traditions also moved into South Africa exogenously from I860, with the arrival of indentured migrants from India, who were largely regulated medically rather than through police enforcement, under the Natal governmental "Coolie Consolidation" Law (no. 2), 1870.19

Cannabis smoking became the concern of colonial governance only from around the turn of the twentieth century after British imperial victory in the South African War (1899-1902).20 In 1910, the Union of South Africa amalgamated the two conquered Boer republics and two British colonies and, three years later, it passed a Natives' Land Act which created boundaries designating "tribal" African territories. In these spaces, the customary authority of monarchs, chiefs and headmen was recognised and subordinated to Pretoria's directives, mediated through a Native Affairs Department. Regional experiences of indirect rule varied.21 Pursuing a modernist and racially segregated society based on Western cultural values, the Union government worked to secure white civil society and an economy underpinned by black labour.22 African wage-working men, many with settled homes in so-called tribal territories migrated as contracted labourers for temporary and unskilled work in the mineral fields of Kimberley and the Witwatersrand, and for commercial farms, harbours and domestic service in towns.

Colonial policing developed to manage this context. Keith Shear situates early twentieth-century policing institutions within the strategies of indirect rule. Native Affairs Department officials recruited and maintained a corps of African constables to keep order in tribal spaces. Yet, into the 1920s, increasing pressures for bureaucratic centralisation saw all officers coming under the institution of the South African Police which, lacking language fluency and personal rapport, diminished effectiveness.23 As Keith Breckenridge and others have shown, policing was founded to monitor the boundaries of race by enforcing the laws that criminalised African mobility.24 The most important of these laws developed during the period of Kruger's Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek, under pressure by British imperial progressives and mining capital interests in the Transvaal.25 Liquor laws, in place from 1896, prohibited African consumption of distilled alcoholic beverages and, along with the Gold Law, normalised search and seize practices directed at labouring men.26 The 1895 (1899) Pass Law, as Breckenridge argues, "set in place the engine of incarceration in South Africa".27 The Urban Areas Act passed in 1923 formalised earlier systems of monitoring the movement ofAfrican people from rural places of residence to and within city workplaces.28

In practice, cannabis control was ancillary to this broader arsenal of laws used to regulate urban and town spaces. Thus, although in the 1940s and early 1950s dagga offences constituted a tiny proportion (1 to 1.4 per cent) of total criminal prosecutions,29 such figures are not a reliable measure of the significance of cannabis prohibition, which gave additional teeth to existing instruments of surveillance, even if unevenly implemented across the territory.30 The comparatively high cannabis seizure reports submitted to the United Nations in the early 1950s must be understood as a feature of these broader colonial controls. In addition, cannabis control was used to regulate migration across national borders.31

Martin Chanock argues that South African legal culture early in the twentieth century nurtured specific ideas about who was criminally dangerous. Suspicion was not directed to "an undifferentiated mass of blacks" but fell rather on "the inhabitants of the racial interface in the urban slums".32 Concerns about dagga - as with alcohol -were linked criminologically to the difficulties of maintaining race segregation in city spaces. Colonial fears were centred on:

... the newly urbanised blacks, the poor whites who mixed with them, and the urban "coloureds" who were seen to inhabit this dangerous societal habitat. The ecology of this world was seen by police, policy makers and the public to revolve around interracial sex, the provision of alcohol by whites to blacks, and the reverse flow of dagga.33

In official views, cannabis was (along with its other attributes) a sign of breakdown between racial and cultural boundaries. For years, cannabis smoking was tolerated in "Native areas" as a communal affair.34 Cannabis law enforcement was long a feature of race politics in towns, cities and certain workplaces.35

However, contradictions and dilemmas of cannabis law enforcement were discernible from the outset. One clash manifested between the prohibitionist aims of the state and the needs of the gold mining industry and its labour-recruiting body, the Employment Bureau of Africa (TEBA). TEBA facilitated worker migration from colonial Mozambique and other parts of Central East Africa. As Perside Ndandu has shown, when border officials apprehended recruits found in possession of any amount of dagga, they were arrested. For a number of years, the Chamber of Mines advanced the funds, taken out of the accused's wages, to pay such fines and - as an alternative to prison - indebted miners were released into the custody of a mine compound.36

Segregation policy itself created a more enduring contradiction for cannabis control. The stability of segregation rested upon a shoring up of customary authority in "Native areas" and, given that cannabis smoking long continued to be a traditional practice of senior and high-status men, there was little incentive to police these territories for cannabis crimes. Over time, these regions afforded opportunities for development and expansion of cannabis cultivation as a cash crop. Officially, local chiefs and those also within the High Commission protectorate of Basutoland, were responsible for eradicating cannabis.37 Under proclamations 265 of 1924 and 116 of 1929, they were required to purge their areas of commercial dagga.38 Yet Basutoland, Swaziland and the "native" territories within the Union nonetheless remained remote niches for unmonitored dagga growing. White-owned farms in South Africa also offered relatively protected growing spaces. In each of these domains, African cannabis entrepreneurs relied upon the cooperation (tacit or direct) of a range of official and unofficial actors within a growing and lucrative dagga supply chain.

In 1929, a traffic in illegal dagga was making headlines in the Union.39 Reading publics learned of the innovative methods through which commodified cannabis moved, by train and automobile, concealed in luggage, hidden among other goods, and carried within the intimate clothing of women. While official reports indicated that most arrests were of African and Coloured men, newspapers depicted cooperative ventures involving men and women - black, brown and white. The magistrate of Weenen in Natal explained how his district had become a "chief supply centre" for the Union, where collusion between white landlords and African tenants facilitated dagga cultivation, harvest and distribution by rail.40 Paarl was an important "disposal depot" in the Cape, and police identified "Native women" as the "chief agents" in railway smuggling.41 Train depots in Natal, the Orange Free State and the Cape had become the nodes of a national dagga-trading network.42

Thus, although drug law enforcement comprised a tool of control over indigenous subjects by colonial and, later, apartheid states, a thriving illegal cannabis economy also constituted an index of its limitations. It confirms Charles van Onselen's caution against viewing the colonial order and its labour systems - which indeed dominated the lives of hundreds of thousands - as functional, total institutions. Van Onselen illustrates the formations of livelihoods within, and resistant to, the "stifling embrace" of controls on the Witwatersrand through the turn-of-the-century life of Mzuzephi Mathebula - the dagga-smoking and ambiguous folk hero, Nongoloza.43Nongoloza and his gang traded in cannabis as part of broader "underworld" livelihoods. They used systems of control for their own advantage, and their fortunes demonstrated the opportunities for collusion between criminal and police.44

Similarly, Gary Kynoch's history of the Marashea gangs in the middle to late decades of the century demonstrates the survival and expansion of urban criminal economies under apartheid, exposing the limits of state hegemony (despite its own self-serving discourses of power).45 Some accounts have suggested that the resistant trade in cannabis should be seen as a form of anti-apartheid activism, arguing that the subversion of state will, with its anti-dagga agenda, and the interracial exchanges occasioned by dagga transactions, represented a progressive politics.46 However, collaboration between urban gangs and South African police in suppressing political dissent into the 1980s, complicate that picture.47 Nonetheless, a robust dagga trade demonstrates the resilience of traditional cannabis practices and also the state's failure to stamp out the new practices that developed with dagga's modern commodification.48

The 1952 Committee Report and the growth of supply-side cannabis policing

The most notable trend in the statistics presented above, using South African police records, is shown by a dramatic spike in the quantity of cannabis seized from the mid-century onwards.49 This indicates the impact of a shift in cannabis policing strategy towards supply-side approaches.

How did this shift in cannabis policing come about? The apparent awakening of a new determination to stamp out dagga coincided, but did not originate, with the May 1948 election victory of the National Party (NP). A month before the elections, the Ministry of Social Welfare of the United Party (UP) government requested that an interdepartmental committee be convened to investigate dagga abuse as a "special social problem".50 The committee formed by the new National Party cabinet submitted its report in 1952 and recommended, along with other measures, that the police focus directly on "destroy[ing] the source" of cannabis supply through the formation of "a limited number of special police dagga squads" to "operate mainly in those areas where the dagga plant is known or suspected to be cultivated".51

Implementing more directed and supply-side strategies transformed cannabis control in South Africa, rendering the policing discussed in this article as a story of two parts.

The roots of re-animated state interest in cannabis suppression in the mid-century in fact lay in the wider reforms undertaken by liberal actors in earlier decades. Drug control represented a progressive impulse attached to ideals of assimilation underpinning measured, but still significant, extensions of political representation for people of colour, as well as welfare benefits and healthcare.52 Deborah Posel observes that a "vision for a new form of state, emboldened and reorganised to drive programmes of economic and social 'uplift' took root in South Africa in the 1930s".53 It arose alongside the state's ambitious pursuit of modern governance, premised on scientific method and expertise. This was a process manifested in practices of record keeping and statistical management, as well as the embrace of government commissions of inquiry as a format for progressive governance.54

In 1937, one such commission, the Commission of Inquiry Regarding the Cape Coloured Population of the Union, published its report. It called for stricter measures for controlling the cannabis trade as means of reducing poverty and crime. Chanock notes that while urban African dagga use was worrisome to colonial officials, "... most complaints about [the use of dagga] related to law enforcement among the coloured community of the Western Cape".55 This commission confirmed repeated claims by the health ministry (in 1924 and again in 1935) that dagga caused criminally violent behaviour.56 It urged that "more active steps be taken to deal with" its control.57

The Union of South Africa was not a signatory to the 1936 League of Nations' Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Dangerous Drugs. But in 1937, the same year the United States passed its Marijuana Act which consolidated state-based control measures under federal law, South Africa passed a Noxious Weeds Act. Dagga was included on a list of plants designated as hazardous, along with well-acknowledged species of agriculturally noxious plants such as burweed and water hyacinth. In 1938, an illustrated bulletin produced and circulated by the Department of Agriculture and Forestry titled

"Weeds in South Africa" explained to farmers that - as a prohibited "narcotic" substance -dagga was now marked for eradication "wherever it occurs otherwise the owner or occupier of land is liable to be prosecuted".58 This was "an additional precaution against Dagga being allowed to grow undisturbed in its wild state".59

As Craig Paterson notes, some in government who spoke to the interests of white farming constituencies considered the Weeds Act to be "fairly drastic", a "measure which enslaves the owner and the public".60 From a policing point of view, the measure removed plausible deniability in instances where growers or owners claimed a lack of knowledge about dagga found on their land. Ongoing claims about dagga's supposed confusion with species of leonotus, an indigenous plant also called "dagga", were refuted by University of Witwatersrand pharmacologists, J.M Watt and Maria G. Breyer-Brandwijk. In 1936, they published an article in the South African Medical Journal. It re-affirmed the Health Department's warnings of dagga's psychological perils and confirmed also that the dagga being seized in high quantities by police was indeed the species cannabis.61

Arrests and seizures of cannabis increased as an effect of these latter 1930s measures, as seen in the police records data appearing in Figures 1 and 2. In 1939, however, police complained that prosecutions for cannabis crimes were being unevenly applied across the territory.62 Moreover, the punishments were no deterrent for an enormously profitable trade and cash crop. Fines, they noted, were easily paid, leaving offenders free to continue as before with their bountiful illicit gains. For example, two men convicted by the Ermelo magistrate for possession of 4 000 lbs of dagga had paid a fine of just over £7. How, the police commissioner asked, was this a genuine punishment when a matchbox of dagga sold for between 3d and 6d?63

One the one hand, magistrates in dagga-growing areas apparently showed leniency, with prosecutions resulting in small fines, a week or two in gaol, or (as in the case of East London) a few "cuts with a light cane".64 By contrast, in the cities, the law was enforced with more gravity. In Cape Town, for example, one Mahomet Potgieter, apprehended with £1 700 worth of dagga was given a maximum sentence of two terms of 6 months with hard labour. Police called for the law to be altered, such that growers would be imprisoned without the possibility of a fine. They wanted land confiscated from landowners who did not dutifully eradicate their dagga crops.65These calls by police for harsher punishments, and a concerted emphasis on supply, presaged later developments when, under the National Party, incipient drives for increased policing powers and harsher punishments would be implemented.66

Meanwhile, in the late 1930s, and through the 1940s, the manufacturing sector was expanding and urban residency by Africans increased. During the Second World War, Smuts relaxed the enforcement of Urban Areas laws. From 1942 to 1946, police were instructed not to check passes and rather to show greater leniency in patrolling African movements within towns.67 Coalitions of progressive African activists and white liberals, active in Joint Council thinktanks created to improve "race relations", saw the extension of health-care, and other forms of state support, including treatment, through a Work Colonies Bill for alcoholics and addicts.68 While some of these initiatives failed to bear fruit, official attitudes to dagga, and the question of its harmful effects - for example as a cause of "native insanity" - became less certain. So too were the previously held certainties about race. Some local medical researchers asserted that distinctions in the mental states of "natives" and "Europeans" were a construct of culture and history.69 In the 1930s and 1940s, Freudian psychiatrist Wulf Sachs, for example, was pointing to discrimination and politics, rather than "nature", when he commented that "the native insane come to the asylum through the gates of the jail more often than do the white insane".70

In this context, in April of 1948, the secretary of Social Welfare, G.A.C. Kuschke, informed the minister that the fifth report of the Coloured Advisory Council was being compiled. The question of cannabis consumption, raised by the Coloured Commission a decade earlier, had again arisen as a "special social problem".71Kuschke explained that the imminent Work Colonies Bill was to provide for "homes for drug addicts, and if it could be established that dagga is a drug then the matter would be in order once the Bill [became] law. If dagga is not a drug it might be necessary to change the bill accordingly". He noted the decade's fluctuating dagga prosecution figures, but suggested that "traffic in this dangerous drug" was "considerable and alarmingly extensive". Dagga smoking, he said, was a "crime producer", and a committee of inquiry, with representatives from the departments of Police, Health, Justice and Social Welfare, should be convened to investigate the matter. This would help pave the way for greater steps to be taken towards eradication of the illegal dagga economy.72

By the following month, however, a new government had been elected. Backlash against weakening race segregation helped garner support for the National Party, which - running on a platform of apartheid - won the 1948 election narrowly and unexpectedly. In July, members of the new NP cabinet turned its attention to Kuschke's earlier suggestion. In August of the following year, it initiated a commission of inquiry for investigation of cannabis as a social malady.73 The interdepartmental Committee on the Abuse of Dagga was comprised of two representatives each from the departments of Health, Welfare, Justice and from Native Affairs, as well as a member of the Department of Police. The committee undertook countrywide research, gathering testimonies and information from a range of institutional and socially located actors. It described informants' views - and its own view - as being generally sympathetic to the "addict" or "dagga-smoker" (as an "unfortunate victim") but condemned the "grower and trafficker".74

The 1952 report described the nature of dagga policing in South Africa to that date as "unusual", in that it was:

... largely the result or the by-product of police activity in other directions and not specifically directed to the detection of dagga offences. The search for evidence of other crimes leads to the discovery of dagga, and the arrest of offenders of all types often results in dagga being found on their persons.75

This of course referred to the racial profiling and controls of black mobility institutionalised in pass laws and other influx controls, which the committee saw as an inadequate proxy for more direct forms of drug policing. The report presented its evidence - ethnographic, medical and psychological. While it conceded that dagga consumption was an "ancient custom" among many indigenous groups, it confirmed a criminological picture of dagga as a "dangerous drug" which, in the modern context, was an "evil" implicated in impoverishment and rising crime rates. It outlined the geographical dimensions of South Africa's "extensive, highly organised, and secret' cannabis economy.76 The "best markets for traffic in the drug" were in the large urban centres. The main sources of supply were "undoubtedly those Native areas where the climate and other conditions, such as inaccessibility, are suitable".77

The crux of the report was a set of recommendations to "substantially reduce" the dagga problem.78 These included a continued measure to quell demand, including through the propaganda of educational campaigns, treating "addicts" and continued arrests for possession. However, the "most effective treatment", it indicated, lay in what was termed "indirect measures" to suppress cultivation and traffic: "The immediate and major effort [was to be] directed against the source grower and trafficker".

Recommendations in this regard included heavier penalties imposed on convicted offenders (including fines of up to £500 and year-long prison terms), the extension of search and seizure powers to officers, the granting of criminal jurisdiction to traditional leaders, and fines and terms of imprisonment for chiefs and headmen who neglected to eradicate cannabis growing in their area. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, it included the formation of mobile police squads to "concentrate on the dagga growing areas and routes leading from those areas... [as] an effective way of combating the dagga evil at its source".79

It is apparent from the police record statistics that raids on crops and the interception of internal and cross-border flows began in earnest in the early 1950s. A newspaper account of a 10-day dagga unit operation in the Middelburg and Nelspruit area in 1953 shows white uniformed police officials posing in front of "one of several hundred heaps" of dagga, along with the "native" assistants who helped detect and uproot it.80 Apprehending the cannabis growers had not been easy, the report explained. In this case, arrests had been hampered by "an effective alarm system. Horns and tom-toms sound ahead of the police raiding squads, who invariably find fields deserted upon their arrival."81 Mountainous areas presented additional challenges. "Detectives in some cases had to be let down by ropes to reach plants under rocks. It was an immense task to cut down the vast crops, and in some cases, axes had to be used."82 Cannabis was destroyed by burning: in sugar processing areas, sugarcane incinerators were adapted temporarily for this purpose.

The focus on supply from the early 1950s, did not mean that urban arrests for possession diminished. The rise in the arrest figures from 1947 (seen in Figure 1) -that is, prior to the Interdepartmental Commission - must also be understood as located in changes taking place within institutions of policing in this decade. As John Brewer explains, there was a 16.7 per cent increase in police membership between 1947 and 1949.83 This may account for the additional capacity to make arrests.

However, there was also an increase of will in the post-war period. Police experienced Smuts's four-year hiatus of pass law enforcement as a loss of power and, when it was lifted in 1946, they were galvanized in a drive to re-assert control.84 It is also likely that this reassertion of police power, for race supremacist ends, also served an institutional impulse to suture wartime tensions among white police officers.85Convictions for possession remained by far the most common type of cannabis conviction. Data from the 1960s which itemised various cannabis offences and their relative proportions, confirm this. For example, in the reporting year for 1963/64, out of 25 911 prosecutions for dagga offences, 90 per cent were for counts of possession, compared with three per cent for cultivation and three per cent for "use".86

Meanwhile, the stakes of rural cannabis livelihoods, particularly for rural growers, became evident in a police raid near Bergville in Natal in 1956, as Ashley Morris recounts. Growers attacked the patrolling officers, killing five (including 3 white) policemen. Twenty-three men were convicted of murder; all but one received the death penalty by hanging.87 The violence of this confrontation and of its aftermath marked a new register of the government's commitment to cannabis prohibition. While envisioned initially as a temporary measure, crop destruction and surveillance of large-scale transport from sites of production to those of consumption, became a mainstay of cannabis policing in South Africa into the twenty-first century.

Conclusion

The statistical and historical picture presented in this article shows the beginnings of supply-side cannabis policing in South Africa, implemented systematically following recommendations by a governmental commission. This is seen in the available arrest and seizure figures, and their ratios in different geographical divisions and districts. During a period when the law remained relatively unchanged, the impact of changes in the rationales and processes of law enforcement practices can be observed empirically. From legal restriction in 1922, cannabis criminalisation gave additional teeth to other controls over black mobility, specifically influx control laws and pass documents. From the early 1950s, a more directed form of narcotic policing emerged. Its focus on targeting growers and mass trafficking routes unsettled the relations that had long fostered more tolerant (or apathetic) approaches to cannabis control.

Although we do not delve in much depth here, the picture of increasingly systematic cannabis policing offered in this article confirms Keith Shear's chronology of post-war developments. There was a move towards policing backed by additional powers and state energy, developments that were "supercharged" with National Party victory and its new will for control. Our account also confirms the more general drive for central bureaucratic efficiency of police record-keeping, which Deborah Posel has recounted. However, as explained in Note Β below, increases of records do not account for the rise in the number of arrests and seizure figures.

In one critical sense, developments in mid-century cannabis policing that followed recommendations made in the Report of the Interdepartmental Committee into Dagga Abuse can be understood as linked to the progressive reforms - as well as to various institutional and political tensions - of earlier decades. Yet, what the specific focus on cannabis policing indicates, as shown by our quantitative data, is a genuinely substantive shift of strategy and reach by the state into new terrain, with immense impact.

However, although this story of cannabis control sits firmly within the groove of apartheid race politics, and increases of police surveillance and force, it also constitutes one of the "ironies" of segregation policy. Contemporary international statistics indicate the comparative success of policing by the South African state - as measured by reported seizures. Yet the continued rise in seizure figures through the decades also document how failures to control cannabis were ensured by the very boundaries - racial and territorial - which the government sought to promote.

***

Notes on the statistical methods used for this article Note A

There are some obvious problems with the data in the UN's 1953 Report of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs as far as "Indian Hemp" is concerned. The data in the table is unevenly populated, with certain years not indicated for some polities (though the relatively high-seizure states like Egypt, Mexico, India, and the United States are shown for all years). It seems probable, too, that despite efforts at standardisation, what constituted a "seizure" may have been defined and measured differently by reporting states. In South Africa, dagga crops confiscated and destroyed from fields and gardens, with the estimated weight of the uprooted "trees", were included in overall tallies. Earlier, the League of Nations reports suggest that in other cases, crop destructions were sometimes considered separately from "seizures"; as for Swaziland, where "in 1945, 20 kilograms, 525 grammes, were seized and 3 881 plants destroyed". See League of Nations Archives, Geneva, Social Affairs, Narcotics Drugs Division, August to November 1946, (605-7-1-3) S-0472, Box 71, File 5, "Review of the Illicit Traffic of Drugs throughout the World, 1940-1945 and the first half of 1946", p27.

Note B

A total of 1 418 records were collected for the period 1932 to I960. At the most disaggregated level, a record represents the number of arrests and quantity of cannabis seized in a district within a division in a specific year. Districts are sub-areas in a division, which approximates to a province or part of a province. Seventy-four districts are represented in the dataset. The number of records per year ranged from 10 districts to 73 districts with a median of 47 districts measured per year (Figure 1). Division boundaries changed over time and divisions can be classified into either 13 (earlier boundaries) or nine divisions (laterboundaries).

Various levels of aggregation were performed for the analysis. For division-level analysis, number of arrests and quantity of cannabis seized were summed from district to division level, and cross-checked with existing division records. For analysis comparing first seven years (1932-1938) and last seven years (1954-1960), or any other grouping of years or districts or divisions, measures were either summed or averaged for the given years.

Statistical analysis is mainly descriptive. The frequency procedure was used to count number of district records per year. Summary statistics such as sum were used to summarise measures within year and means were used to average measures across years. Percentages were used to calculate proportion of measures for a given set of categories, for example number of arrests for a specific division were divided by total arrests for all divisions and then multiplied by 100 to obtain proportion of arrests per division. Spearman's rho correlation was used to measure correlation between the sum of arrests per record by year and the sum of amount dagga seized per record per year. Bar charts are used to represent sum of arrests per year, and sum of amount dagga seized per year. Pie charts are used to represent proportion of arrests by division and proportion of amount dagga seized for selected periods.

A number of qualifications can be noted for assessing the accuracy of the data presented here. The reports used did not break down arrests by the specific charges (e.g. possession, sales, or cultivation) or contain information about prosecutions and convictions, as later reports did. Nor does this dataset reveal identifiers such as race and gender, though some of this information is found elsewhere. The statistics, moreover, cannot be read naively as a transparent window on historical realities. They cannot account for variation in district reporting across these years nor, for example, whether the absence of a given district report for a given year reflects an absence in cannabis-related crimes, an administrative oversight, or other circumstances. The number of police reports found in the file, and the information they contain, must be understood as products of bureaucratic and political processes, subject both to clerical error and interested manipulation. It is also the case that the physical boundaries of district and divisions were subject to some shifting during these decades, introducing territorial inconsistencies of reporting entities across the period covered in this study. However, notwithstanding some of these factors, and controlling for others, a useful picture of general trends is discernible here, one which triangulates with the "qualitative" historical record.

Another feature of this police report data is that the rising overall number of annual reports submitted to government rose across the period covered. Rises of arrests and seizures are, however, not explained by rising numbers of reports submitted to the Pretoria office, nor by natural increases in the population. To control for number of records, total arrests and total lb seized were divided by number of records for each year. Strong significant positive correlations were found between total arrests per record and year (Spearman's rho 0.602, p<0.050) and total lb seized per record and year (Spearman's rho 0.823, p<0.050).

There is an obvious possibility that earlier reports may have gone missing (and the low numbers of reports for 1933 seem especiallysuspect), affecting the figures. While this may be the case, it is also likely that increased reporting reflected a growth in police capacity, bureaucratic rationality and responsiveness to centralised police directives. Across the period under study, the number of police officers in the Union grew, also proportional to increases in the general population. For example, in 1932, with a population of just over 8 million, there were 1.19 police per 1 000 of the population; in 1954, the population was 14 million with 1.63 police per 1 000.

Note C

Our attempts to verify this extraordinary figure, or otherwise rule out a reporting error or similar, were unsuccessful. A search of key newspapers for mention of high-yield police operations in the area during 1955 proved fruitless (although we did find newspaper reports from 1953 for Nelspruitarea).

REFERENCES

Breckenridge, K., The Biometric State: The Global Politics of Identification and Surveillance in South Africa, 1850 to the Present (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2014). [ Links ]

Brewer, J.D., Black and Blue: Policing in South Africa (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1994). [ Links ]

Burrows, E.,A History ofMedicine in South Africa (Balkema, Cape Town, 1958). [ Links ].

Chanock, M., The Making of South African Legal Culture 1902-1936: Fear, Favour and Prejudice (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001). [ Links ]

Chattopadyaya, U., "Dagga and Prohibition: Markets, Animals, and Imperial Contexts of Knowledge, 1893-1925", South African HistoricalJournal, 71,4 (2019). [ Links ]

Christopher, A.J., "The Union of South Africa Censuses, 1911-1960", Historia, 56, 2 (2011). [ Links ]

Dubow, S. and Jeeves, A., South Africa's 1940s: Worlds of Possibilities (Juta, Cape Town, 2005). [ Links ]

Du Toit, B.M., "Cannabis Sativa in Sub-Saharan Africa", South African Journal of Science, September 1974. [ Links ]

Du Toit, R., "Dagga as a Weed", in Weeds in South Africa, Department of Agricultural and Forestry, Reprint No. 1,1938. [ Links ]

Duvall, C., TheAfrican Roots ofMarijuana (Duke University Press, Durham: NC., 2019). [ Links ]

Gillespie, K., "Containing the 'Wandering Native': Racial Jurisdiction and the Liberal Politics of Prison Reform in 1940s in South Africa", Journal of Southern African Studies,37,3 (2011). [ Links ]

Glaser, C., Bo-Tsotsi: The Youth GangsofSoweto, 1935-1976 (Heinemann, Portsmouth, 2000). [ Links ]

Gordon, D., "From Rituals of Rapture to Dependence: The Political Economy of Khoi-Khoi Narcotic Consumption, c. 1487-1870", South African Historical Journal, 35, 1 (1996). [ Links ]

Guy, J., "An Accommodation of Patriarchs: Theophilus Shepstone and the Foundations of the System of Native Administration in Natal", Journal of Natal and Zulu History (2018). [ Links ]

Hadley, P., Doctor to Basuto, Boer and Briton, 1877-1906 (David Philip, Cape Town, 1972). [ Links ]

Kynoch, G., We are Fighting the World: A History ofthe Marashea Gangs in South Africa, 1947-1999 (Ohio University Press, Athens, 2005). [ Links ]

La Hausse, P., "The Cows of Nongoloza': Youth, Crime and Amalaita Gangs in Durban, 1900-1936", Journal of Southern African Studies, 16, 1 (1990). [ Links ]

Mills, J., Cannabis Britannica: Empire, Trade and Prohibition, 1800-1928 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2003). [ Links ]

Mills, J.H. and Richert, L. (eds), Cannabis: Global Histories (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2021). [ Links ]

Morris, A., "Weeding Out' the Nature of the Ngoba Dagga Raid Killings of 1956", BA Honours essay, University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2011. [ Links ]

Ndandu, P., "Dagga in the Gold Mining Era: Tension in Work, Culture and Market (1926-1950)", BA Honours essay, University of Johannesburg, 2018. [ Links ]

Nkosi, P.I., "Dagga in Mid-century South Africa: Impacts of Criminalisation and Policing, 1932-1960", MA dissertation, University of Johannesburg, 2020. [ Links ]

Ntsebeza, L., Democracy Compromised: Chiefs and the Politics of Land in South Africa (HSRC Press, Cape Town, 2006). [ Links ]

Paterson, P., "Prohibition and Resistance: A Socio-Political Exploration of the Changing Dynamics of the Southern African Cannabis Trade, c. 1850 to the Present", MA Dissertation, Rhodes University, 2009. [ Links ]

Posel, D., "The Case for a Welfare State: Poverty and the Politics of the Urban African Family in the 1930s and 1940s", in Dubow, S. and Jeeves, A. (eds), SouthAfrica's 1940s: Worlds of Possibilities (Juta, Cape Town, 2005). [ Links ]

Posel, D., "Mania for Measurement: Statistics and Statecraft in the Transition to Apartheid", in Dubow, S. (ed.) Science and Society in South Africa (Manchester University Press, Manchester and NewYork, 2000). [ Links ]

Roos, N., "Work Colonies in South African Historiography", Social History, 36, 1 (2011). [ Links ]

Sachs, W., "The Insane Native: An Introduction to a Psychological Study", South AfricanJournalof Science, 30 (1933). [ Links ]

Seekings, J., "The Carnegie Commission and the Backlash at Welfare State-Building in South Africa, 1931-1937",Journal of Southern African Studies, 34, 3 (2008). [ Links ]

Shear, K., "At War with the Pass Laws? Reform and the Policing of White Supremacy in 1940s South Africa", The HistoricalJournal, 56,1 (2013). [ Links ]

Shear, K., "Tested Loyalties: Police and Politics in South Africa, 1939-1963", The Journal ofAfrican History, 53, 2 (2012). [ Links ]

Shear, K., "Chiefs or Modern Bureaucrats? Managing Black Police in Early Twentieth Century South Africa", Comparative Studies in Society and History, 54, 2 (2012). [ Links ]

Sparks, S., "The Apartheid Project",in Magaziner, D. (ed.) Oxford Handbook of South African History (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2020) [ Links ]

Suid-Afrikaanse Akademie vir Wetenskap en Kuns (SAAWK), Volksgeneeskuns in Suid-Afrika: 'n Kultuurhistoriese Oorsig, Benewens 'n Uitgebreide Boererate (Pretoria, Protea Books, 2010 [1965]). [ Links ]

Van Onselen, C., "Crime and Total Institutions in the Making of Modern South Africa: The Life of Nongoloza Mathebula", History Workshop, 19 (1985). [ Links ]

Van Onselen, C, New Babylon, New Nineveh: Everyday Life on the Witwatersrand, 1886-1914 (Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg and Cape Town, 1982). [ Links ]

Waetjen, T., "An Overdose in the Archive: Opioids and Harm in South African History", in Waetjen, T. (ed.), Opioids in South Africa: Towards a Policy of Harm Reduction (HSRC Press, Cape Town, 2019). [ Links ]

Waetjen, T., "Dagga: How South Africa Made a Dangerous Drug", in Mills, J.H. and Richert, L. (eds), Cannabis: Global Histories (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2021). [ Links ]

Waetjen, T., "Global Opium Politics in Mozambique and South Africa, c. 1880-1930" South African Historical Journal, 71,4(2019). [ Links ]

Watt, J.M., and Breyer-Brandwijk, M., "The Forensic and Sociological Aspects of the Dagga Problem in South Africa", South African Medical Journal, 10(1936). [ Links ]

1 Namely, the Drugs and Drug Trafficking Act and Section 22A (9) of the Medicines and Related Substances Control Act.

2 "Industrialising Cannabis to Grow Economy", SABC News, Accessed 9 June 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oYRHyBZl-u4&t=2s

3 U. Chattopadyaya, "Dagga and Prohibition: Markets, Animals, and Imperial Contexts of Knowledge, 1893-1925", South African Historical Journal, 4, 2019, pp 587-613; T. Waetjen, "Dagga: How South Africa Made a Dangerous Drug", in J.H. Mills and L. Richert (eds), Cannabis: Global Histories (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2021).

4 M. Chanock, The Making of South African Legal Culture 1902-1936: Fear, Favour and Prejudice, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001), pp 92-96; J.H. Mills, Cannabis Britannica: Empire, Trade and Prohibition, 1800-1928, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2003), pp 160-161.

5 Statutes of the Union of South Africa, 1927-28, "Medical, Dental and PharmacyAct No. 13 of 1928" (Government Printer, Cape Town, 1928), Section 61, Subsection 1 (b and c),p232.

6 Statutes of the Union, Medical, Dental and Pharmacy Act of 1928, p 242.

7 T. Waetjen, "An Overdose in the Archive: Opioids and Harm in South African History", in T. Waetjen (ed.), Opioids in South Africa: Towards a Policy ofHarm Reduction (HSRC Press, Cape Town, 2019).

8 National Archives of South Africa (hereafter NASA), South African Union Archives (hereafter SAB) VWN 1342 473/1-17 United Nations (UN) Economic and Social Council, Commission on Narcotic Drugs, Eighth Session, Item 15 of the provisional agenda, "The Problem of Indian Hemp", 19 March 1953. Annexure Table: Seizures of Indian Hemp, its Resin, and Preparations Made (copy).

9 NASA, SAB: Social Welfare (hereafter VRN) 1342 473/1-17, Commission on Narcotic Drugs Report, Table: Seizures of Indian Hemp, its Resin, and Preparations Made (copy).

10 P. I. Nkosi, "Dagga in Mid-Century South Africa: Impacts of Criminalization and Policing, 1932-1960", MA dissertation, University of Johannesburg, 2020. Nkosi created this database from documents in the file NASA, SAB, South African Police (hereafter SAP) 216 36/ 112/31. She checked some of this data against records in SAB, SAP 534 36/2/55. Record keeping continued after Republic in 1961, but after 1963 was through different channels. See Notes A, Β and C at end of article for methodological explanation.

11 National Library, Pretoria. Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the Abuse of Drugs (hereafter GroblerReport), (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1970), p 137.

12 Methods by which police estimated the amounts of cannabis seized in police raids may have varied across time and locale. For many records a direct measurement of lb cannabis seized was reported but for others a more indirect estimate was derived. For example, a 1939 report on a raid in Ermelo calculated the seizure of 2,716 "trees" to be approximate 4 000 lbs, or about .68 lbs per individual plant. See NASA SAB Justice Department files (hereafter JUS) 955 1/840/26/1 Deputy Commissioner of Police to Police Commissioner, Pretoria, "Illicit Dagga Traffic", 13 March 1939.

13 South Africa experienced a severe drought in the 1960s. It is unclear from the available seizure data whether or how this had an impact on cannabis cultivation.

14 Grobler Report, p 137.

15 In 1939-40: Pietersburg (36,2 per cent), Middelburg (15,3 per cent), Ermelo (13,9 per cent) in the Transvaal and Vryheid (5,0 per cent), Ixopo (5 per cent), Dundee (4 per cent) in Natal were highest contributors to national total lbs seized. In 1943-1944: Middelburg (31,4 per cent) and Ermelo (4,6 per cent) in the Transvaal and Dundee (13,2 per cent), Vryheid (9,7 per cent), Eshowe (8,3 per cent) and Ixopo (3,4 per cent) in Natal were highest contributors to national total lbs seized. During 1943-1944 one district outside Transvaal and Natal, Bethlehem in the Free State, made a significant contribution - 9,4 per cent - to the national total.

16 B.M. du Toit,"CannabisSativa in Sub-Saharan Africa", SouthAfrican Journal ofScience, September 1974, pp 266-270; D. Gordon, "From Rituals of Rapture to Dependence: The Political Economy of Khoi-Khoi Narcotic Consumption, c. 1487-1870" South African Historical Journal, 35, 1, 1996, pp 62-88; and C. Duvall, The African Roots of Marijuana, (Duke University Press, Durham: NC, 2019).

17 P. Hadley, Doctor to Basuto, Boer and Briton, 1877-1906 (David Philip, Cape Town, 1972), pp 130-135; E. Burrows, A History of Medicine in South Africa (Balkema, Cape Town, 1958), pp 190-194; Suid-Afrikanse Akademie vir Wetenskap en Kuns (SAAWK), Volksgeneeskuns in Suid-Afrika: 'n Kultuurhistoriese oorsig, benewens 'n uitgebreideBoererate. (Protea Books, Pretoria, 2010 [1965]).

18 Gordon, "From Rituals of Rapture".

19 Waetjen, "Dagga".

20 Waetjen, "Dagga".

21 L. Ntsebeza, Democracy Compromised: Chiefs and the Politics of Land in South Africa (HSRC Press, Cape Town, 2006); J. Guy, "An Accommodation of Patriarchs: Theophilus Shepstone and the Foundations of the System of Native Administration in Natal", JournalofNatalandZulu History, 2018, pp 81-99.

22 The Union's 1921 census counted 6 928 580 in the population as a whole; in 1960, it had risen to just over 16 million. As cited in A.J. Christopher, "The Union of South Africa Censuses 1911-1960", Historia, 56, 2, 2011, p 5.

23 K. Shear, "Chiefs or Modern Bureaucrats? Managing Black Police in Early Twentieth Century South Africa", Comparative Studies in Society and History, 54, 2, 2012, pp 251274. For a more general summary of these pressures, see D. Posel, "Mania for Measurement: Statistics and Statecraft in the Transition to Apartheid", in S. Dubow (ed.) Science and Society in South Africa (Manchester University Press, Manchester and NewYork, 2000).

24 K. Breckenridge, The Biometric State: The Global Politics of Identification and Surveillance in South Africa, 1850 to the Present (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2014), pp 69, 72-38.

25 C. van Onselen, New Babylon, New Nineveh: Everyday Life on the Witwatersrand, 18861914 (Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg and Cape Town, 1982), pp 48, 64-65, 69-73,106; Breckenridge, BiometricState, p 73.

26 Breckenridge, BiometricState, pp 70-71.

27 Breckenridge, BiometricState, p 72.

28 Chanock, South African Legal Culture, p 432.

29 NASA SAB VWN: 1342 473/1-17, "Annexure A" submission: "Request for Additional Information" to the United Nations. Data from 1952 shows that this tiny proportion of criminal prosecutions compared to other crimes in the same period as follows: 2 to 2.3 per cent for grievous bodily harm; 4.5 to 6.3 per cent for common assault; 6 to 7 per cent for drunkenness; and 7.8 to 9.3 for pass law violations. See Report of the Interdepartmental Committee on the Abuse of Dagga, South Africa: Union Government 31/52 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1952), p 9.

30 Shear, "Chiefs or Modern Bureaucrats".

31 T. Waetjen, "Global Opium Politics in Mozambique and South Africa, c. 1880-1930", South African Historical Journal, 71,4, 2019, pp 560-586.

32 Chanock, South African Legal Culture, p 70.

33 Chanock, South African Legal Culture, p 70.

34 Waetjen, "Dagga".

35 Waetjen, "Dagga".

36 P. Ndandu, "Dagga in the Gold Mining Era: Tension in Work, Culture and Market (1926-1950)", BA Honours essay, University of Johannesburg, 2018.

37 League of Nations Archive, Geneva: "Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs, Annual Reports by Governments for 1943, Basutoland", p 2; Report of the Interdepartmental Committee on theAbuse ofDagga (hereafter RICAD), Union of South Africa: Union Government31/52 (Government Printer, Pretoria,1952), p 26.

38 RICAD, p 35.

39 "Dagga Danger in the Cape / A Corollary of the Slum Evil? / Vigorous Police Campaign / 544 Cases before Local Courts this Year", Cape Times, 18 July 1929.

40 NASA SAB: Secretary of Native Affairs (hereafter NTS): 8194 3/345 Weenen Magistrate to Chief Native Commissioner, Pietermaritzburg, 13 December 1929.

41 "Dagga Danger", Cape Times, 1929.

42 These were: New Formosa, New Furrow and Weenen in Natal; Generals Nek, Tweeling, Wepener, and Kaalspruit, in the OFS; and Macclear and Ndabakazi in the Cape. See SAB NTS 8194 3/345 Asst. Native Commissioner Cape Town to Secretary for Native Affairs Pretoria, 27 November 1929.

43 C. van Onselen, "Crime and Total Institutions in the Making of Modern South Africa: The Life of Nongoloza Mathebula", History Workshop, 19,1985, p 65.

44 Van Onselen, "The Life of Nongoloza". See also P. la Hausse, "'The Cows of Nongoloza': Youth, Crime and Amalaita Gangs in Durban, 1900-1936", JournalofSouthernAfrican Studies, 16, 1, 1990, pp 79-111; C. Glaser, Bo-Tsotsi: The Youth GangsofSoweto, 19351976, (Heinemann, Portsmouth 2000.)

45 G. Kynoch, We are Fighting the World: A History ofthe Marashea Gangs in South Africa, 1947-1999 (Ohio University Press, Athens, 2005), pp 2-7.

46 For example, C. Paterson, "Prohibition and Resistance: A Socio-political Exploration of the Changing Dynamics of the Southern African Cannabis Trade, c. 1850 to the Present", MA Dissertation, Rhodes University, 2009, pp 54-58.

47 Kynoch, Fighting the World, pp 117-130, especially 7-9 and 58.

48 S. Sparks, "The Apartheid Project",in D. Magaziner (ed.) Oxford Handbook of South African History, (Oxford University Press, October, 2020) available at https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921767.001.0001/ox fordhb-9780190921767-e-11 (DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921767.013.1).

49 Further and more refined use of this police record database, especially at district level, will be able to draw out social and environmental complexities of cannabis policing and policing geographies in South Africa.

50 NASA: JUS 955 1/840/26/1, Part 2, "Dagga Smoking as a Special Social Problem", G.A.C. Kuschke, Secretary for Social Welfare, 29 April 1948.

51 R/CAD,p36.

52 See S. Dubow and A. Jeeves (eds) South Africa's 1940s: Worlds of Possibilities (Juta, Cape Town, 2005); J. Seekings, "The Carnegie Commission and the Backlash at Welfare State-Building in South Africa, 1931-1937", Journal of Southern African Studies, 34, 3, 2008, pp 515-537; and K. Gillespie, "Containing the 'Wandering Native': Racial Jurisdiction and the Liberal Politics of Prison Reform in 1940s South Africa", Journal ofSouthern African Studies, 37, 3, 2011, pp 499-515.

53 D. Posel, "The Case for a Welfare State: Poverty and the Politics of the Urban African Familyin the 1930s and1940s", in Dubow and Jeeves, South Africa's 1940s, p 65.

54 Posel, "Mania for Measurement".

55 Chanock, South African Legal Culture, p95.

56 League of Nations Archive, Geneva: Health, Social, and Opium 1928-1946,15529 2931, Dagga, a drug used in South Africa, 1/11 3217; and Pamphlet: J.A. Mitchell, "Dagga Smoking and its Evils: Memorandum by the Union Department of Public Health, June 1924". See also Chanock, South African Legal Culture, p95.

57 . Chanock, South African Legal Culture, p 95; and Paterson, "Prohibition and Resistance", pp 54-58.

58 R. du Toit, "Dagga as a Weed", in Weeds in South Africa, Department of Agricultural and Forestry, Reprint No. 1,1938, pp 6,10. United States's influences were evident in the description of the plant's "narcotic" effects, which referenced United States' Dispensary.

59 Du Toit, "Dagga as a Weed", p 6.

60 Paterson, "Prohibition and Resistance", p 54.

61 J.M. Watt and M.G. Breyer-Brandwijk, "The Forensic and Sociological Aspects of the Dagga Problem in South Africa", South African Medical Journal, 10, August 1936, pp 573-579.

62 NASA: SAB JUS 955 1/840/26/1, Deputy Commissioner of Police to Police Commissioner, Pretoria, "Illicit Dagga Traffic", 13 March 1939.

63 NASA: SAB JUS 955 1/840/26/1, Deputy Commissioner of Police to Police Commissioner, Pretoria, "Illicit Dagga Traffic", 13 March 1939.

64 NASA: SAB JUS 955 1/840/26/1, Office of the Attorney General, Cape Town, Circular No. 4 to all public prosecutors, "Illicit Dagga Traffic", 31 March 1939; Solicitor General, Grahamstown, Schedule of prosecutions/sentences, 19 April 1939, with Annexures.

65 NASA: SAB JUS 955 1/840/26/1, Secretary of Social Welfare, "Dagga Smoking as a Special Social Problem", 29 April 1948.

66 K. Shear, "At War with the Pass Laws? Reform and the Policing of White Supremacy in 1940s South Africa", The HistoricalJournal, 56,1, 2013, pp 205-229.

67 Shear, "At War with the Pass Laws?"

68 N. Roos, "Work Colonies in South African Historiography" Social History, 36, 1, 2011, pp 54-76.

69 For example, W. Sachs "The Insane Native: An Introduction to a Psychological Study", SouthAfricanJournalofScience, 30,1933, pp 706-713.

70 Sachs, "The Insane Native", p 707.

71 NASA: SAB JUS 955 1/840/26/1, Secretary of Social Welfare, "Dagga Smoking as a Special Social Problem", 29 April 1948.

72 NASA: SAB JUS 955 1/840/26/1, Secretary of Social Welfare, "Dagga Smoking as a Special Social Problem", 29 April 1948.

73 RICAD, p v.

74 RICAD, p 3.

75 RICAD, p 8.

76 RICAD, p 42.

77 RICAD, p 3.

78 RICAD, p 45

79 RICAD,p44.

80 "Lowveld Combed in SA's Biggest Dagga Raid", Rand Daily Mail, 18 February 1953, p 9.

81 "SA'sBiggestDaggaRaid".

82 "SA's Biggest Dagga Raid".

83 J.D. Brewer, Black and Blue: Policing in South Africa (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1994), p 197.

84 Shear, "At War with Pass Laws?"

85 K. Shear, "Tested Loyalties: Police and Politics in South Africa, 1939-1963", Journalof African History, 53, 2, 2012, pp 173-193. Many English-speakers supported Smuts's South African involvement in the war, and a sizeable number of them were deployed. Dissenting Afrikaans-speaking officers who supported the German forces were interned, were regarded with suspicion, and were side-lined.

86 Grobler Report, p 137. The remaining four per centwas classified as "other".

87 A. Morris, "'Weeding Out' the Nature of the Ngoba Dagga Raid Killings of 1956", BA Honours essay, University ofKwaZulu-Natal, 2011.