Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Historia

On-line version ISSN 2309-8392

Print version ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.64 n.2 Durban Nov. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8392/2019/v64n2a2

ARTICLES

Satyagraha prisoners on Natal's coal mines

Kalpana Hiralal*

Professor of History at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In 1913 under the leadership of Gandhi, the first "mass" political resistance was launched in South Africa. The key sites of resistance were in Natal and the Transvaal. This resistance was popularly known as the Satyagraha campaign or the Indian Strike. Well over 20 000 men, women and children engaged in protest action against discriminatory legislation that restricted their economic, social and political mobility. The historiography of the 1913 Satyagraha Campaign is substantial, but there are gaps of coverage on the incarceration and treatment of prisoners. The coal mines in the Natal Midlands became another site of resistance in the aftermath of the campaign. This article documents prisoner/captor relations in the aftermath of the campaign on the coal mines. Indian prisoners were subjected to flogging, poor rations and at times, ringleaders were assaulted severely. These lesser known narratives add to the current historiography by highlighting mine authorities' attitudes and policy towards prisoners in the context of control, repression and coercion as well as the nature of the prisoner and captor relationship in the Satyagraha campaign of 1913.

Key words: Indians; satyagraha; coal mining; resistance, Natal.

OPSOMMING

Die eerste massa-politiese verset in Suid-Afrika is in 1913 onder Gandhi se leiding van stapel gestuur. Die belangrikste liggings van hierdie verset was in Natal en Transvaal. Hierdie verset staan algemeen bekend as die satyagraha-veldtog oftewel die "Indiese Staking". Méér as 20 000 mans, vroue en kinders was betrokke by die protesaksie teen diskriminerende wetgewing wat hul ekonomiese, sosiale en politiese mobiliteit beperk het. Die historiese literatuur oor die satyagraha-veldtog van 1913 is omvangryk: daar is egter gapings in die dekking van gevangenskap en die behandeling van gevangenes. Die steenkoolmyne op die Natalse Middelland het nóg 'n ruimte vir verset geword na afloop van die veldtog. Hierdie artikel dokumenteer gevangene-merverhoudings op hierdie steenkoolmyne na afloop van die satyagraha-veldtog. Indiese gevangenes het deurgeloop onder geseling, swak rantsoene en, met tye, die swaar aanranding van die belhamels. Hierdie minder-bekende narratiewe dra by tot die bestaande historiografie deur die mynowerhede se houding en beleid teenoor gevangenes binne 'n konteks van beheer, onderdrukking en dwang uit te lig; asook die aard van die gevangene-gevangenemerverhouding gedurende die satyagraha-veldtog van 1913.

Sleutelwoorde: Indiërs; satyagraha; steenkoolmyne; verset; Natal.

Introduction

The satyagraha movements undertaken by the Indian community in the Transvaal (1907-1911) and in 1913 are one of the dominant narratives of resistance in South African historiography in the first quarter of the twentieth century. At the turn of that century, South Africa was a politically stratified and racially segregated society. The Cape and Natal were for the most part English-speaking settler colonies with responsible government while the white residents of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State (OFS) were primarily Afrikaans speaking and were independent Boer republics. However, the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) led to the incorporation of both the Transvaal and the OFS under British rule.1 British rule was organised on the premise of racial segregation, with colonialists occupying privileged positions. The Indian community, who arrived in Natal either as indentured labourers or free Indians from the 1860s onwards, were subject to various discriminatory legislation that restricted their economic, political and social mobility.

In the Transvaal, between 1907 and 1911 the Indian community embarked on the first satyagraha campaign, a non-violent protest campaign against discrimination and injustice. Its supporters were known as passive resisters or satyagrahis. The campaign was initially in response to the Asiatic Law Amendment Act, No. 2 of 1907 (also known as the "Black Act"), which required that all Asian males be registered and fingerprinted and carry a certificate (a pass) at all times. In the same year the Transvaal's Immigration Restriction Act imposed an education test on all future immigrants to the colony and established the Immigration Department to check against illegal Asiatic entries.2 Resistance to these measures was confined primarily to the Transvaal, with the merchant class taking the lead. The government of the Transvaal and later the government of the Union of South Africa resorted to severe punishments to break the non-violent resistance.3 The courts sentenced hundreds of Indians to imprisonment with hard labour. Men were obliged to embark on hunger strikes because of the conditions in prisons. Indian Opinion, a local Indian newspaper, asked in its 3 October 1908 edition, "Should Indians be starved into submission?"4

A second non-violent protest movement was undertaken in 1913. Many resisters were assaulted and wounded and several were killed by the police or employers. On the coal mines in the Natal Midlands there were numerous reports by Indian passive resisters and prisoners of ill-treatment and physical abuse by mine officials and policemen. For example, at the Durban Navigation Colliery at Dannhauser, an Indian mine labourer, Appana, accused David Jenkins, a miner, of "unlawful assault".5 Annamarrai, a "free" ( Indian labourer at Ballengeich mine also accused the compound manager, Edward James Roberts, of slapping "my face with his open hand" when he refused to work underground alone.6

The Satyagraha Campaign of 1913 was the first mass mobilisation of Indians in South Africa against discriminatory and unjust laws. As yet, in the vast corpus of literature on this campaign, the treatment of resisters in the aftermath of the campaign has not been fully contextualised, analysed or documented. One of the earliest accounts penned on the subject was the book Satyagraha in South Africa, dictated by Gandhi in an Indian prison from 1922 to 1924 and completed while he was recuperating from illness after his release. In the preface to the book he wrote,

I have neither the time nor the inclination to write a regular detailed history. My only object in writing this book is that it may be helpful in our present struggle, and serve as a guide to any regular historian who may arise in the future.7

While the book does include discussion on certain important aspects of South African prison conditions it is based mainly on Gandhi's recollections. Furthermore, it does not capture detailed accounts of how the satyagrahis were treated by their employers on the coal mines.8

Scholars have since focused largely on the socio-economic background to the campaign, the role of Gandhi, the role of the Indian masses and on the campaign's global impact.9 A study by Surendra Bhana and Neela Shukla-Bhatt provides literary and cultural perspectives of this struggle.10 Gendered perspectives have sought to assign women's agency in this movement. Of these, the primary focus has been on the Searle judgement, the collective mobilisation of women on the coal mines and plantations and the implications of women's participation for traditional gender roles.11 However, an analysis of prison conditions, prison-captor relations and treatment of resisters has thus far been a neglected aspect of satyagraha historiography. Indeed, the only documented accounts of prison conditions are the personal reminisces of well-known resisters such as Bhawani Dayal and Raojibhai Patel. They participated in the 1913 struggle and were imprisoned. Even their accounts, however, provide only cursory and minimal insight into individual incarceration, describing the meals they were given, their solitary confinement and daily experiences.12 In Pioneers of Satyagraha: Indian South Africans Defy Racist Laws, 1907-1914 (2017), E.S. Reddy and the present author have published a comprehensive study of the satyagraha movement in South Africa between 1907 and 1913. This book shifts the focus from Gandhi and examines the motivations of the resisters. However, while it has a chapter on prison conditions, it does not explore in detail how resisters were treated on the coal mines in the aftermath of the satyagraha struggle.13

This article adds to the above literature in that it highlights lesser-known aspects of the 1913 Satyagraha campaign, and focuses in particular on its aftermath and on the relations between prisoner and captor. Using archival sources such as medical reports, affidavits, testimonials, official correspondence as well as contemporary newspapers, it provides rich insights into employer attitudes, conditions of capture, prison treatment and resistance.14 It reveals that the overall trend of mine authorities was one of increased control and coercion over satyagraha prisoners. The site of analysis is the coal mines of the Natal Midlands, which was one of the key areas of mobilisation and resistance in the 1913 Satyagraha campaign.

Events leading to the 1913 Satyagraha Campaign

The arrival of indentured and "Free" or "passenger" Indians from 1860 onwards, changed the economic, political and social landscape of South Africa.15 Indentured immigrants laboured along the coastal regions of Natal in the tea and sugar plantations, on the railways and were employed as domestic servants. As labourers they were subject in many instances, to poor living and working conditions. There were numerous complaints of physical and sexual assaults, of verbal abuse, exploitation, and of poor rations and housing. However, by the late 1890s it was the Free Indians - ex-indentured and "passenger" Indians - who became targets of racial discrimination.

After their contracts had expired many indentured men and women refused to re-indenture and opted to engage in livelihoods such as hawking, fishing and retail trade. Many "passenger" Indians, too, eked out a livelihood as small-scale traders, hawkers and engaged in other menial work. But the colonial trader found it increasingly difficult to compete with the thrifty mode of living and competitive prices of the Free Indian petty trader. They were perceived as a "menace" to colonial trade and livelihood. Both the colonial - and later Union - governments, seeking to appease the white electorate instituted discriminatory legislation that curbed the political, economic and social mobility of Free Indians. For example, in 1896 the introduction of the £3 annual tax stipulated that time-expired indentured workers could only remain in the colony if they re-indentured or paid the stipulated tax.16 This was the first serious attempt by the Natal colonial government to prevent the permanent settlement of Indians in Natal.

The laws governing indentured labour did not apply to "passenger" Indians, therefore there was no legal restrictions to their entry to Natal and the Cape. Subsequently, to discourage immigration and trade in Natal, the Immigration Restriction Act (No. 1 of 1897) and the General Dealers Licensing Act (No. 18 of 1897) were enacted. The immigration law sanctioned the entry of new immigrants only after they had passed a compulsory education test, while the legislation on granting a trading licence was designed to restrict Indians from embarking on trading activity. It empowered town councils and town boards to be the final arbiter on issuing trade licenses. There was no recourse to appeal if such licenses were declined.17

However, by 1913, two significant issues served as a catalyst to mobilise the Indian community at a national level, transcending religion, class, caste, language and ethnic differences. The first was a judgement given in the Cape Supreme Court in March 1913 by Justice Malcolm Searle in the case of Esop v the Minister of the Interior. In effect, the judgement declared that all non-Christian Indian marriages, unless legalised before a civil marriage officer or the "protector" of Indian immigrants, contracted within or outside South Africa, irrespective of their religious custom, were invalid. Thus the judgement did not affect indentured or ex-indentured women as their marriages were registered with the protector of Indian immigrants and local magistrates.18 But the judgement had serious implications for "passenger" Indian women, whose marriages were solemnised by priests in India, not recognised by South African law. They were of the opinion that the Searle judgement reduced their "status from that of being honoured and honourable wives of their husbands to one of concubinage".19 Indian women were outraged at the judgement, for it was an insult to their womanhood and had serious implications for family migration and inheritance and raised questions regarding the legitimacy of their children.20

The second issue was the failure of the Union government to remove the £3 tax. Collectively, these issues rallied the Indian community. Given that most Indians were living in the Transvaal and Natal, it was decided to defy the inter-provincial immigration laws which required permits. Hence, crossing Volksrust, the border town between Natal and the Transvaal, became the primary target of satyagraha resistance. On 6 November 1913 there were 2 037 men, 127 women and 57 children who participated in the "Great March" crossing the Volksrust border and seeking to enter the Transvaal without a permit. Hundreds of satyagrahis were arrested and imprisoned.

Satyagraha prisoners

The satyagraha campaign of 1913, unlike the first of 1907, was far more widespread, taking place in Natal, the Transvaal, and even the Cape Province. It drew support from various groups: traders, merchants, hawkers, teachers, lawyers, labourers from the mines and others from the coastal districts of Natal. Significantly, it included many women and children. Most resisters were fined or given the option of three months' imprisonment. The vast majority opted for imprisonment. Many served their sentences in Durban and Pietermaritzburg prisons. There were numerous complaints by resisters of verbal and physical abuse and of the inhumane manner in which they were treated in prison. For example, some prisoners took offence to being called "coolies".21 Prison food was often described as inedible, "half-cooked", and there were complaints that rice was poorly prepared and sometimes the rice tins contained "weevils".22

These complaints gave rise to resistance in the prisons. Hunger strikes by resisters became a common act of defiance. Prisons became another site of nonviolent resistance in the 1913 Satyagraha campaign. In the Pietermaritzburg prison 60 resisters went on a hunger strike. Amongst them were Parsee Rustomjee, Manilal Gandhi and Ramlal Gandhi. Rustomjee was prevented from wearing his "sacred thread", which he found unacceptable and an affront to his religion.23 Another passive resister, a vegetarian, was "forcibly fed" with milk mixed with eggs.24

Appendix 1 below, "Statements made by Indian Passive Resisters (from Pietermaritzburg) at the Durban prison on 2 December 1913 before the Chief Magistrate", highlights clearly the reasons for embarking on a hunger strike. For example, Rowashanker (a student from the Phoenix settlement), Bhaga (a student in Johannesburg) and Naganbhai, refused to eat because their "little wants" were not supplied. The common items requested by all three resisters were boots, socks and sandals. Other items were, "a clean coat", salt to clean their teeth, a book, and a belt for the waist. Rowashanker, Bhaga and Naganbhai were adamant that they would not consume food unless their "little wants" were met.25 Clearly, the statements by the hunger strikers reveal that they were deeply committed to their cause and were prepared to suffer for their actions. Engaging in a hunger strike was the only means of protest in prison. Whether the requests of the resisters were met is unknown, as no follow-up data is available on how the prison authorities and state responded. However, the treatment of satyagraha prisoners and the stance taken by the hunger-strikers, gained media attention and enhanced the commitment of supporters.

Resistance on the coal mines

The Indian labourers on the coal mines in the Natal Midlands played a pivotal role in the 1913 satyagraha struggle. The coal mines were a major employer of indentured and free Indian labour. In 1897, there were 342 indentured men who had volunteered to work on the mines, by 1906 there were more than 1 000 men employed there. By 1909 the number had increased to over 3 2 0 0.26 By December 1913 a total of 3 705 Indians were employed on 12 collieries. As many as 2 854 of the Indians were indentured workers while 851 were "free" Indians.27

The coal mines became a key site for satyagraha resistance. Most of the Indians were indentured and were not yet liable for the payment of the £3 tax. They had no serious grievances against the mine management but were in solidarity with the free Indians who were liable for the £3 tax, and they "wish[ed] have the £3 tax repealed".28 The strike on the mines commenced during the latter part of October 1913 when Gandhi proceeded to Newcastle to mobilise support amongst mine workers. On 23 October 1913, the 300 miners at St George's Colliery, 850 at Natal Navigation, 500 at Glencoe, 100 at Hatting Spruit and 300 at New Shaft, staged a strike. Railway workers, at Glencoe and at Hatting Spruit, were also on strike. The Dundee and District Courier reported on 23 October: "The Collieries at Newcastle, Dannhauser, Ingagane and Hatting Spruit as well as the railways to that point are affected and nearly the whole of the Indians' employed are out. There is no disorder..."29

Mine officials described the Satyagraha campaign of 1913 as the "Indian Strike" and "Indian coolie "Passive Resistance' strike".30 The Indian mine labourers disliked this pejorative description and being labelled as "strikers"; they viewed their show of resistance as "a [mere] demonstration".31

Indian mine labourers formed part of the "Great March" when they crossed the Transvaal border in November 1913. Many were arrested at Balfour, south-east of Johannesburg, and returned by rail to the coal mines. They were given a day's respite, and several decided to return to work, while others who refused to do so, were arrested and sentenced to short periods of imprisonment.

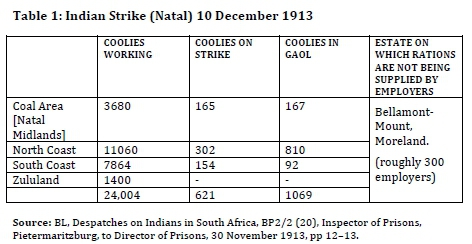

One of the key challenges that both mine and prison authorities faced with returning strikers was with regard to their incarceration. The main problem was where to house the prisoners. Neither the government nor the mine managers had experienced a situation on this scale before. On 12 November, Rifleman Taylor arrived in Newcastle with 145 Indians prisoners who were sentenced as follows: 31 to a £5 fine or three months' imprisonment; 109 to £5 or 6 months' imprisonment; four young men received lashes with a sjambok, and one was sentenced to a £5 fine, which he opted to pay. On 13 November, 32 Indian prisoners were escorted to the Newcastle magistrate's office. Their sentences were: 31 indentured Indians received 7 days on the mines and one was sentenced to three months' imprisonment or the payment of a fine of £5. In Newcastle, on 19 November, a total of 299 resisters were sentenced, of whom 208 were free and 91 indentured (see Table 1 below). Overall, the sentences imposed varied from fines between £1 to £10 with the option of imprisonment.

However, there were inadequate prison facilities available. As Table 1 shows, the majority of the resisters opted for imprisonment rather than to pay the fines. By choosing imprisonment the number of arrested strikers caused congestion in the existing prisons, creating a dilemma for prison authorities and mine officials on how and where to incarcerate the resisters. The local prisons in Newcastle and surrounding areas such as Dundee were already filled to capacity. The only viable solution available to the authorities was to convert mine compounds to prisons to house the strikers.32 The government and mine officials therefore opted for sentences to be served on the mines where the Indian workers were employed. Subsequently, in both Dundee and Newcastle, compounds in certain collieries were designated and turned into out-station prisons. In Dundee the following collieries served as outstation prisons:

Burnside Collieries, No. 1 shaft

Burnside Collieries, Nos. 2 shaft

South African Collieries

Wallsend Malangeni Collieries

Natal Navigation Collieries, No. 1 shaft

Natal Navigation Collieries, No. 2 shaft

Natal Navigation Collieries, No. 3 shaft

Glencoe Collieries

St. George's Collieries

Hatting Spruit Collieries.

[In Newcastle], the western side of the compound at Ballengeich Collieries was used as an outstation to the Newcastle Gaol.33

As Table 3 shows, Ballengeich had the largest number of resisters confined to mine compounds - a total of 172 by 19 November 1913. It was at the Ballengeich mines that rumours first surfaced of floggings by mine officials to compel returning resisters to work. There were protests from the Indian community and the Indian government also expressed concern. Dossen Lazarus, chairman of the Passive Resistance Committee at Newcastle submitted affidavits by Indians miners to Sergeant E.H. Purdon of the South African Mounted Riflemen (SAMR). Lord Gladstone, the governor-general sent a telegram to the prime minister of the Union of South Africa on 25 November 1913, seeking urgent clarification on the "Indian complaints":

I earnestly hope that General Smuts will himself make searching enquiry at prison out-stations; have Indian complaints brought before him; as far as possible afford public demonstration of falsity of statements; and take necessary action if illegal violence on part of gaolers and warders has in fact occurred. I need scarcely point out to you that it is of the first importance to Indian Government that official denials should be followed by responsible statement of Minister after inquiry on the spot, and that I am only asking for what South Africa itself has right to expect.34

Given the seriousness of the matter, the Attorney General in Natal wrote to Purdon to investigate. He instructed that Indian strikers be interviewed and required that all the affidavits to be taken separately and on the same day so "that none of them can compare notes after signing their affidavits, and let them tell their own stories."35 In addition, the attorney general and the director of Prisons, C.P. Batho, called for a report from the inspector of Prisons, G. Mardall.36

Below is an account of the treatment of Indian strikers at Ballengeich Colliery based on these affidavits, and on official correspondence and newspaper accounts. The affidavits highlight several issues: prisoner ill-treatment; allegations of floggings; coercion and control by authorities; and the mines as sites of political resistance.

Prisoner resistance at Ballengeich Colliery in November 1913

At Ballengeich Colliery, at Ingagane, Newcastle, there were 330 Indians and 400 Africans working on the mines in November 1913. Over half of the Indian miners participated in the satyagraha campaign, and 190 were arrested at Balfour, in the Transvaal. On 10 November, the compound manager for Ballengeich Mines, Edward James Roberts, and the mine manager, Edward Headley Hutt, went to Hatting Spruit to rein in the striking miners. On 11 November Hutt and Roberts returned with the resisters escorted by two white and two African constables.

Back at the mine, the authorities were keen to get striking Indians back to work. The Indians were taken to the mine compound where they were addressed by Hutt, Roberts and the Sirdar (headman). Hutt advised them to return to work, warning them that failure to do so would result in no rations being issued and imprisonment on the mines. But most remained defiant and only about "half a dozen stepped out" to resume work.37 The defiant Indians were asked to sit aside and were guarded by a strong police contingent.

December 1913; BL, BP2/2 (20), "Despatches on Indians in SA", Governor-General to Secretary of State, 6 January 1914. A full investigation was halted and the AGO deferred the matter until the commission of inquiry was set up and its findings were made known.

Being incarcerated in make-shift prison compounds aggrieved the resisters. Furthermore, they were instructed to construct a prison fence. Poles and wires were brought to the compound to facilitate the building of the compound prison and according to one of the strikers, Syed Badsha, they were informed that they would be "fenced in and be taken to work in the morning and locked inside in the evening" just as the "Bambata natives" [had been].38 The resisters objected to compound prisons and determined instead to march to Newcastle, demanding to be incarcerated in a "government goal".39 According to Taylor, the striking Indians became very "excited" and unhappy. They were not challenging imprisonment itself, but the location of their imprisonment. They wanted to be incarcerated in Newcastle not within make-shift prison compounds.

The Indian strikers had the support of their fellow workers and their families, in particular that of the wives of Indian labourers. These women challenged the strikers to be defiant, raising questions about their masculinity if they accepted poor treatment with equanimity. According to Puckrie Pillay, a time-keeper at the mine, two Indian women "started to abuse the men saying they were not men and [asking] why did they not march on to Newcastle".40 According to the medical practitioner, J.A. Nolan of Newcastle, "one woman was evidently urging the Indians on".41 Indian strikers subsequently marched towards the Newcastle prison.

On their way to Newcastle, they met with resistance from the mine officials and government police. Many would complain that the manager of the Ballengeich mine took part in flogging the retreating Indians.42 From testimonies, it becomes evident that guns, rifles, sticks and sjamboks were the main tools in the violence that took place at the colliery. However, affidavits by mine officials, compound and mine managers, SAMR policemen and mine engineers claim that they were acting in self-defence and that sticks and sjamboks were necessary to disarm a "threatening", "riotous" and armed mob. According to the testimony of Chief Nkabana of the Newcastle division, who was known as "Dokotela Ndaba" (alias Sibiya), "We tried to stop them, and told them to wait ... but they would not stop. One of the Indians picked up a bone and threw it at a policeman named Mtshali and hit him on the back of his right foot".43 Hutt also claimed that he had been acting in self-defence:

The Indian who was leading the mob struck me on the hand with a stick. I then retaliated when he seized the sjambok ... I was dodging the stones which were being pelted at me by the others ... I then used my sjambok to drive them [the Indians] back into the Compound. The other men and the Native police then joined in.44

Another witness, John Cunningham, a blacksmith employed at Ballengeich Colliery reinforced Hutt's testimony, "... one of the Indians struck him [Hutt] on the hand with either a stick or a stone", and thus it had been necessary to use "force" to disarm the striking Indians.45 According to Roberts, he found "the Indians gesticulating and brandishing their sticks about 400 yards from the Compound".46 Chief Nkabana added that a few Indians refused "to give up their sticks [and] we gave [them] a cut or two until they gave them up".47 Taylor was adamant that, "Only sufficient force was used to meet the first rush and only against those who were threatening with sticks".48 To hasten the retreat of the striking Indians to the compound, two warning shots were fired in the air. The Indians were overpowered and forced to retreat to the mine compound. Defiant resisters were addressed by the Newcastle magistrate, Douglas G. Giles through an interpreter. He explained to them that he had arrived on instructions from the government and believed that they were "misguided" and had "broken the law by running away". He added, "what you have just done was not passive resistance" and that he now had to "look upon them . as rioters".49

Testimonials from striking Indian miners at Ballengeich, however, contradicted the affidavits of the mine management and police who had described the Indians as "threatening", "riotous" and armed. These statements reveal that many miners were subjected to brutal floggings and physical abuse. According to one Indian striker, Syed Badsha, the men were disarmed before being flogged by police and mine officials.50 Mahomed Nabbi (Saiboo), a free Indian, concurred, stating in his affidavit, "I did not see any Indians using sticks or stones".51 The striking Indians were asked to remove their hats "and they took away all the sticks we had with us. After this the Manager, Compound Manager, and a Native Induna started to strike the men with sjamboks ...".52 According to Mannikam, an Indian labourer and striker,

The Manager, Compound Manger, Cunningham and Sibiya struck me a number of blows. Two of our party fell from the blows, and we had to turn back, Gouden Nair and Isoop [Essop] fell. The two who fell were taken away on stretchers.53

Govinden (a free Indian labourer) claimed that he was unarmed when he was attacked by Cunningham who was on horseback, "[He] struck me on back with sjambok and I ran away and the engineer came up and with the butt end of a rifle struck me on my left side, I dropped and became unconscious."54

Duseph, another free Indian labourer, further stated that the compound manager "struck me with a sjambok saying that I should not drink water, and also that the mines' butcher struck me in the eye with his fists and another blow in the face with his fists ..."55

Treatment of "agitators"

Mine officials also had hostile interactions with strikers who provided leadership in the satyagraha campaign on the mines. They were often described as ringleaders or "agitators" responsible for both intimidation and violence.56 They were particularly sought out and dealt with separately. Mine officials feared their presence would bring the mines to a standstill by encouraging other miners to strike. The testimonials of these "agitators" and strikers reveal that mine officials were "merciless" in their treatment of them.

Among the known ringleaders at the Ballengeich mines were, Annamalay, Rajiah, Syed Badsha, Babhoo, Mahomed Abdool, Manikum, Jaymungal Singh and Rajoo. A free Indian labourer, Lellie Channie, describes the physical assaults on ringleaders as "merciless".57 He states,

The Manager Mr Hut[t] and the Compound Manager Mr [Edward James] Roberts went on flogging the supposed leaders without a word to them and then they were passed on to the Natives who delivered a further course of flogging and finally [they were] locked in the Office".58

According to Annamalay,

... he [the compound manager] beat eight [ringleaders] altogether, and as he finished with them passed each over to the manager, who gave them a further flogging with a sjambok. The manager then passed them over to the native police [four] who again beat them with sjamboks, sticks and fists and then were placed in a room and locked up. The others were then flogged with sjamboks as they were sitting and were taunted with having followed Gandhi.59

In his affidavit Mannikam went on to say that some of the men "had to dig holes for poles" and Indians strikers were "forced to assist".60 Abdullah concurred,

... a European Govt Police caught me by the arm, and as I was being taken towards a room, the Manager using both hands struck me a blow on right forearm with a sjambok, then another blow at the end of the sjambok struck me near right eye.61

Jaymungal Singh, a free Indian, stated that Mahomed Nabbi (alias Saiboo) was told to remove his cap and was then beaten severely by the mine manager, Cunningham, and other mine employees. Singh described his assaults by the manager and Sibiya as follows,

He struck me on back with sjambok about 5 blows. He caught me by the neck and pulled me forward and as I fell forward the Compound Manger struck me several blows on back with sjambok. [Then] Sibiya caught me by the collar and pushed me into the room and locked me up. 62

Syed Badsha described his ordeal, claiming that the compound manger,

... caught me by the right arm and the Manager struck me with a sjambok on left side and shoulders and I was then handed to Cunningham who struck me with a sjambok on the same side whilst he held my right arm. Then I was handed over to the Engineer who had a short stick and struck me two or three blows on my head. Then he handed me over to the man who works at the Butcher's shops and he kicked me on the buttocks and slapped my head. He handed me to Sibiya, and he struck me on the head with a sjambok, and caught me by the shirt collar and pushed me into the police room and locked me in.63

Mahomed Nabbi (Saiboo), claimed that the mine manager struck him "4 or 5 blows on my back", and the compound manager then "struck me 3 blows from the side with a sjambok and then Mr Cunningham struck me about 4 blows . Then the European lamps room man one blow . I was quite dizzy with these blows".64

Medical reports submitted by general practitioners on the physical health of the prisoners substantiate these claims and provide insight into the nature and frequency of the floggings at Ballengeich. These reports of alleged floggings at Ballengeich were serious enough for the Natal Indian Congress (NIC) and government officials to launch an investigation. Medical examinations were conducted by the district surgeons, Dr Sutherland, Dr Charles Cooper and Dr J.A. Nolan of Newcastle.65The report submitted by Cooper, who examined the ringleaders at the Newcastle prison on 13 November 1913, shows evidence of physical assaults by some of the mine officials. Indeed, the physical examinations revealed that the ringleaders such as Mannikam, Syed Badsha, Abdool, Ramantak, Mahomed Nabbi and Jaymungal Singh had "bruises on their back . with marks of stick or sjambok". The methods used by mine officials was clearly aimed at suppressing the activity of the ringleaders and any future uprisings on the mines. Cooper submitted the following report:

Mannikam 961: Bruises left back, complains of pain in back and chest: V inch cut over left eye: small scalp wound right ocular region.

Syed Batsha (Badsha) 960: Bruises on back: marks of stick or sjambok, bruised left thumb.

Abdool 962: Abrasion across the face: swollen left jaw: bruise left side of back.

Ramantak 964: Bruises across back, one on left scapular region and one right scapular region.

Mahomed Nabbi 966: Bruises on back left scapular region. Old marks of lashes. Jaymungal Singh: Bruises across back.66

Annamalay, Rajiah, Syed Badsha, Babhoo, Mahomed Abdool, Mannikam, Jaymungal Singh and Rajoo, were taken to Newcastle. Of the group seven were sentenced to £5 or the option of 6 months' imprisonment and one received a sentence of £5 or the option of three months' imprisonment.

While Cooper's examination revealed that the ringleaders had been brutally treated, he did not make similar findings for the vast majority of the prisoners. On 14 November 1913, he examined 134 free Indian prisoners and reported that their overall health was "good".67 Table 4 below provides a list of names of all prisoners who were examined and comments on their "state of health". Of the 134 prisoners, 23 had complained of illnesses; two of the injuries were suffered when "alighting [from] the train", and 29 had complained of injuries related to the violence on the mine.68

A perusal of the medical report indicates that the vast majority of the prisoners were judged to be "fit" and in good health. There were no serious injuries recorded. The most common medical complaints (23 prisoners) were "pain in the back", headache, fever, stomach pains and diarrhoea.69 A few complained of injuries received due to the outbreak of violence on 11 November 1913 on the mine. Further common complaints regarding physical assaults included an abrasion of the right [side of the] face; pain in the back; a small cut on the heel; bruises on [the] right thigh; [injury sustained when a] horse tramped on the foot; a scalp wound and a bruised shoulder. 70

Both Nolan and Cooper concluded that some prisoners were faking their assaults. Nolan had been on site on 11 November when the Indian strikers returned to Ballengeich. He maintained that the returning strikers were very "noisy" and "armed with sticks and behaved in a threatening manner and that the mine employers drove them back with their sjamboks".71 Nolan attended to a few strikers who were assaulted during the violence that erupted at Ballengeich. He challenged the statements of some of the strikers, arguing that their statements were false and misleading.72 Cooper, after examining Iniarpillay and Gouden at Ballengeich mine, was convinced that they were "shamming" their bruises. He discovered that Iniarpillay had a "slight bruise" on his back and that Gouden had a bruise on the left upper arm and his left side. "That was all the injuries these two had . [although] evidently [they were] blows from sticks and sjamboks".73 He added that Chindran had showed him what appeared to be an "old injury", which was a growth on his arm, claiming that it was a bruise from a beating. It was in fact "too old to be that". In his affidavit, Cooper added that he had witnessed no floggings at Ballengeich Colliery.74

Under pressure from both the NIC and the Indian government, the Union government requested an investigation by the prison authorities. The director of prisons, C.P. Batho, called for a report from G. Mardall, the inspector of prisons who was based in Pietermaritzburg. Mardall submitted a preliminary report on 30 November 1913. He concluded that floggings and assaults on Indians had indeed occurred at Ballengeich out-station on 11th of November 1913 while they were trying to leave the mines for the Newcastle prison. He added that strikers, after their conviction by the magistrate in Newcastle on 12 November, had "shown no unwillingness to perform their tasks and no violence has been used to compel them to work ...".75

The outbreak of violence at Ballengeich Colliery led to one fatality. This was of Nagadu (Nargiah), a labourer, who died on 17 November 1913. According to fellow worker Duseph, Nagadu had been struck by "two natives", one of whom was Sibiya, and the compound manager, with a sjambok, "I saw it with my own eyes", he stated.76Annamalay supported Duseph's statement. He was adamant that he had witnessed the compound manager beating Nagadu.77 However, the medical reports by both Dr Cooper and Dr Sutherland of Newcastle, recorded evidence to the contrary. They reported that Nagadu had in fact died of pneumonia, caused by "exposure", and they did not find any evidence or signs of wounds of flogging or any other ill-treatment.78In his preliminary report on 30 November 1913, Mardall concurred with the two doctors, Cooper and Sutherland, that Nagadu had died from natural causes, but acknowledged that there was evidence indicating that while in custody he had been subject to "rough treatment".79

Indian strikers also had serious complaints regarding the quality of the food provided to those who were incarcerated. On their arrival at the Ballengeich mine from Hatting Spruit (not far from Dundee), they complained of extreme hunger having not eaten a proper meal for days. The mine manager and compound manager did provide food rations but without any cooking facilities such as pots and pans or coal. According to Lellie Channie, a free Indian, Indian prisoners were only given a can of rice and dholl "without any pots or any other cooking necessities, consequently we starved through the night and in the morning".80 Nevertheless, the Indians managed to acquire some tins which they used as pots and could use the rice that was given to make a meal. In his affidavit Channie also alluded to the kindness of some of the local people, saying that "I remember a white man gave us a slice of bread each which I think is out of his own pocket and pity".81

Conclusion

In conclusion, the treatment of prisoners on the Ballengeich coal mines in the Natal Midlands during the Satyagraha campaign of 1913 highlights three crucial aspects of the history of these events. Firstly, with regard to the relations between prisoners and their captors during this period, it is clear that the mine authorities were seeking to quell prisoner resistance by control and coercion. The existing evidence clearly reveals that there was some degree of prisoner abuse in terms of floggings. Ringleaders who organised resistance were intimidated and assaulted. Moreover, neither the mine authorities nor the provincial authorities or Union government had planned adequately for the housing and feeding of the satyagrahi prisoners. The number of resisters sentenced during the 1913 campaign overwhelmed both the state and the mine authorities. In the Natal Midlands, inadequate prison facilities exacerbated the problems of imprisonment and forced the authorities to create makeshift prison camps on mine premises.

Secondly, the mines became yet another site of resistance in the aftermath of the 1913 campaign. Indian resisters wanted to be imprisoned in "proper" prisons with adequate facilities rather than in makeshift camps put up hastily on mining sites. The dissatisfied Indians challenged the mine officials by marching to Newcastle in protest. This defiance was not only an act of resistance but was also indicative of their desire to be treated fairly.

Thirdly, this article reveals that relations between prisoner and captor remain one of the least researched, or indeed researchable, aspects of the 1913 Satyagraha Campaign. The narratives reproduced here highlight the responses of capitalist employers to political resistance in the early twentieth century and also the need to examine one of the first mass movements in South Africa from diverse perspectives. This trajectory of study will add to new histories of resistance in South African historiography.

REFERENCES

Arkin, A. J., "The Contribution of the Indians to the Economic Development of South Africa, 1860-1970: A Historical Income Approach", PhD thesis, University of Durban Westville, 1981. [ Links ]

Beall, J., and North-Coombes, D., 'The 1913 Natal Indian Strike: The Social and Economic Background to Passive Resistance, Journal of Natal and Zulu History, VI (1983). [ Links ]

Bhana, S., and Dhupelia, U., "Passive Resistance among Indian South Africans", Unpublished paper presented to the conference of the South African Historical Association, University of Durban-Westville, July 1981. [ Links ]

Bhana, S., and Shukla-Bhatt, N., A Fire that Blazed in the Ocean: Gandhi and the Poems of Satyagraha in South Africa, 1909-1911 (Promilla & Co., New Delhi, 2011). [ Links ]

Bhana, S., and Brain, J., Setting down Roots: Indian Migrants in South Africa, 1860-1911 (Wits University Press, Johannesburg, 1990). [ Links ]

Dayal, B., Swami Bhawani Dayal Sanyasi, Pravasi Ki Atmakatha/ The Autobiography of a Settler, Translated from Hindi (Rajhans Publications, New Delhi, 1947). [ Links ]

Gandhi, M.K., Satyagraha in South Africa (Navajivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad, 1961). [ Links ]

Govinden, B., and Hiralal, K. (eds), 1913, Satyagraha, Passive Resistance and its Legacy (Manohar, Delhi, 2015). [ Links ]

Guha, R., Gandhi before India (Penguin, London and New Delhi, 2013). [ Links ]

Hiralal, K., "Rethinking Gender and Agency in the Satyagraha Movement of 1913", Journal of Social Sciences, 25 (2010). [ Links ]

Hiralal, K., '"Our plucky sisters who have dared to fight': Indian Women and the Satyagraha Movement in South Africa", The Oriental Anthropologist, 9, 1 (2009). [ Links ]

Mongia, R., "Gender and the Historiography of Gandhian Satyagraha in South Africa", Gender and History, 18 (2006). [ Links ]

Patel, R.M., The Making of the Mahatma Based on Gandhijini Sadhana. Adaptation in English by Abid Shamsi (Ravindra R. Patel, Ahmedabad, 1990). [ Links ]

Reddy, E.S., and Hiralal, K., Pioneers of Satyagraha: Indian South Africans Defy Racist Laws, 1907-1914 (Navajivan, Ahmedabad, 2017). [ Links ]

Swan, M., "The 1913 Natal Indian Strike", The Journal of Southern African Studies, 10 (1984). [ Links ]

* Her research interests are the South Asian diaspora and gender and resistance in South Africa. Her most recent co-edited publication is with Z. Jinnah, Gender and Mobility in Africa, Borders, Bodies and Boundaries (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2018).

1 The Anglo-Boer War (also known as the South African War) was fought between Britain and the Boer republics in South Africa from 1899 to 1902.

2 Indian Opinion, 29 August 1908; M. Gandhi, Satyagraha in South Africa (Navajivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad, 1961), pp 34-35.

3 The Union of South Africa was established in 1910.

4 Indian Opinion, 3 October 1908.

5 Natal Archives Depot (hereafter NAD), Pietermaritzburg (hereafter PMB), Attorney General's Department (hereafter AG), 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich Colliery Compound (special gaol) and allegation that Magistrate, Newcastle, authorized floggings", Testimony of Appana, Magistrate's Court, Newcastle, 23 December 1913.

6 NAD, PMB, AG, 938/1913, Rex vs Edward James Roberts, Magistrate's Court, Newcastle, 15 December 1913.

7 Gandhi, Satyagraha in South Africa, pp xiv-xv. Because this book was written from memory it has some errors. See also E.S. Reddy and K. Hiralal, Pioneers of Satyagraha: Indian South Africans Defy Racist Laws, 1907-1914 (Navajivan, Ahmedabad, 2017).

8 Refer to chapters VI and XII, 'Women in the Frontline" and "Prison Conditions and Deportations", in Reddy and Hiralal, Pioneers of Satyagraha.

9 S. Bhana and U. Dhupelia, "Passive Resistance among Indian South Africans" Unpublished paper at South African Historical Association Conference, University of Durban-Westville, July 1981; J. Beall and D. North-Coombes, "The 1913 Natal Indian Strike: The Social and Economic Background to Passive Resistance", Journal of Natal and Zulu History, 6 (1983), pp 48-81; M. Swan, "The 1913 Natal Indian Strike", Journal of Southern African Studies, 10 (1984), pp 239-58; B. Govinden and K. Hiralal (eds), 1913, Satyagraha, Passive Resistance and its Legacy (Manohar, Delhi, 2015). See also Ramachandra Guha, Gandhi before India (Penguin, London and New Delhi, 2013).

10 S. Bhana and N. Shukla-Bhatt, A Fire that Blazed in the Ocean: Gandhi and the Poems of Satyagraha in South Africa, 1909-1911 (Promilla & Co., New Delhi, 2011).

11 R. Mongia, "Gender and the Historiography of Gandhian Satyagraha in South Africa", Gender and History, 18 (2006), pp 130-149. See also K. Hiralal, "Rethinking Gender and Agency in the Satyagraha Movement of 1913", Journal of Social Sciences, 25 (2010), pp 71-80; and K. Hiralal, "Our Plucky Sisters who have Dared to Fight: Indian Women and the Satyagraha Movement in South Africa", The Oriental Anthropologist, 9, 1 (2009), pp 1-22.

12 R.M. Patel, The Making of the Mahatma, Adaptation into English by A. Shamsi (R.R. Patel, Ahmedabad, 1990); and B. Dayal, S. Bhawani, D. Sanyasi, P. Ki Atmakatha, The Autobiography of a Settler, Translated from Hindi (Rajhans Publications, New Delhi, 1947).

13 Reddy and Hiralal, Pioneers of Satyagraha, pp 161-173.

14 This article is based on archival and newspaper sources, notably from Indian Opinion, which documents the struggle, names of resisters, employer attitudes, prison sentences and ill-treatment. Archival sources were found in the British Library (BL) the Natal Archives (NAD) in Pietermaritzburg and Talana Museum in Dundee. For example, sources at the BL, provided data on resisters on mines and coastal plantations in Natal; testimonials of satyagraha prisoners and details of the British government's response to allegations of floggings. The Attorney General Office (AGO) papers at the NAD, have reports by medical practitioners, affidavits by mine officials on the incarceration of prisoners on Ballengeich mines. Monthly reports by the Commissioner of Mines, accessed from the Talana Museum, provide information on mine officials' attitudes and policy towards the satyagraha struggle.

15 "Passenger" Indians were those immigrants who arrived unencumbered by labour obligations but were subject to normal immigration laws.

16 Reddy and Hiralal, Pioneers of Satyagraha, pp 3-17.

17 British Library (hereafter BL), London, Public & Judicial Collection, IORL/PJ/8/293, "Memorandum on the Position of Indians in the Union of South Africa submitted to the United Nations 1946, Segregation of Indians, South Africa, Emigration", pp 1-3.

18 Indian Opinion, 5 April 1913.

19 Indian Opinion, 5 April 1913; and 12 April 1913.

20 Indian Opinion, 5 April 1913.

21 Indian Opinion, 15 October 1913; Reddy and Hiralal, Pioneers of Satyagraha, p 169.

22 Indian Opinion, 10 December 1913; Reddy and Hiralal, Pioneers of Satyagraha, pp 170-171.

23 The Sacred Parsi thread.

24 Reddy and Hiralal, Pioneers of Satyagraha, p 171.

25 Indian Opinion, 10 December 1913; BL, BP2/2 (20), Despatches on Indians in South Africa, "Statements made by Indian Strikers (from Pietermaritzburg) at the Durban Gaol, 2 December 1913, before the Chief Magistrate, Durban, with regard to their treatment at the Gaol".

26 A.J. Arkin, "The Contribution of the Indians to the Economic Development of South Africa, 1860-1970: An Historical Income Approach", PhD thesis, University of Durban Westville, 1981, p 67.

27 Gandhi Luthuli Documentation Centre (hereafter GLDC), University of KwaZulu-Natal (hereafter UKZN), Bhana Collection (hereafter BC), 1107/454, "Report of the Protector of Indian Immigrants for the Year ended 31st December 1913".

28 NAD, PMB, AG 764/13, "Re: Alleged Flogging of Indians at the Ballengeich Colliery on 11th November 1913", Attorney General to Secretary for Justice, Pretoria, 22 December 1913.

29 Indian Opinion, 29 October 1913.

30 Talana Museum, Dundee (hereafter TM), Commissioner of Mines (hereafter CM) 123/1913, Monthly Report of the Deputy Commissioner of Mines, Province of Natal, for the Month of October 1913.

31 TM, CM 123/1913, Monthly Report of the Deputy Commissioner of Mines, Province of Natal for the Month of October 1913.

32 NAD, PMB, AG 4/13, Attorney General to Secretary for Justice, Pretoria, 22nd December 1913.

33 BL, BP2/2 (20), Despatches on Indians in South Africa, Telegram from Lord Gladstone to General Botha, 25 November 1913.

34 BL, BP2/2 (20), Despatches on Indians in South Africa, Telegram from Lord Gladstone to General Botha, 25 November 1913.

35 NAD, PMB, AG. 764/13, Attorney General to Sergt Purdon, SAMR, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich Colliery Compound (special gaol) and Allegation that Magistrate, Newcastle, Authorized Floggings", 28 November 1913.

36 NAD, PMB, AG 764/13, Attorney General to Public Prosecutor, Newcastle, 22

37 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich Colliery Compound (special gaol), and allegation that Magistrate, Newcastle, authorised the floggings", Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 12 December 1913.

38 TM, Natal Mine Managers' Association, Minutes of Meeting, 8 November 1913. The reference was to the "Bambatha rebellion" of 1906 when the Zulu people protested against a new tax. The rebellion was suppressed brutally by the authorities.

39 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich Colliery and allegation that Magistrate Authorized Floggings", Testimonial of Rajiah, Court of the Magistrate, Division of Newcastle, 23 December 1913.

40 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimonial of Puckrie Pillay, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 12 December 1913.

41 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich ", Testimonial of J A Nolan, MD, Magistrate's Office, 15 December 1913.

42 Indian Opinion, 26 November 1913; NAB PMB, A.G. 764/13, Attorney General to Secretary for Justice, Pretoria; "Alleged Flogging of Indians at the Ballengeich", 11 November 1913 and 22 December 1913.

43 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich Colliery and Allegation that Magistrate Authorized Floggings", Testimonial of Dokotela Ndaba, KaNkunga, Chief Nkabana, Magistrate's Office, 12 December 1913.

44 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Edward Headly Hutt, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 11 December 1913.

45 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of John Cunningham, Magistrate's Court, Newcastle, 11 December 1913.

46 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Edward James Roberts, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 11 December 1913.

47 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich Colliery", Testimony of Dokotela Ndaba, KaNkunga, Chief Nkabana, Magistrate's Office, 12 December 1913.

48 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", A.S. Taylor Rfm SAMR 1229, to S.S.M. Curtis SAMR, Ballengeich Colliery, 14 November 1913.

49 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Secretary for Justice to Attorney General, Natal, 22 December 1913.

50 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Syed Badsha, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 6 December 1913.

51 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Mahomed Nabbi (Saiboo), Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 12 December 1913.

52 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Mahomed Nabbi (Saiboo), Magistrate's Office, 12 December 1913.

53 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Mannikam, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 6 December 1913.

54 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Govinden, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 12 December 1913.

55 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Duseph, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 12 December 1913.

56 Indian Opinion, 31 October 1913.

57 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Lellie Channie Newcastle, 3 December 1913.

58 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Lellie Channie Newcastle, 3 December 1913.

59 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Annamalay, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 22 November 1913.

60 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Mannikam, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 6 December 1913.

61 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Abdulla, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 6 December 1913.

62 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Jaymungal, Magistrate's Office, 12 December 1913.

63 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Syed Badsha, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 6 December 1913.

64 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Mahomed Nabbi (Saiboo), Magistrate's Office, 12 December 1913.

65 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Dr Charles Cooper, District Surgeon, to Magistrate Newcastle, 15 November 1913; and Testimony of J.A. Nolan, MD, Magistrate's Office, 15 December 1913.

66 Cited verbatim from NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, Public Prosecutor to Attorney General, 22 December 1913.

67 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Charles Cooper, District Surgeon to Magistrate Newcastle, 15 November 1913.

68 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Cooper to Magistrate Newcastle, 15 November 1913.

69 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Cooper, to Magistrate Newcastle, 15 November 1913.

70 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Cooper, to Magistrate Newcastle, 15 November 1913.

71 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimonial of J.A. Nolan, MD, Magistrate's Office, 15 December 1913.

72 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich Colliery", Testimonial of J.A. Nolan, MD, Magistrate's Office, 15 December 1913.

73 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich Colliery", Dr Charles Cooper, District Surgeon to Magistrate Newcastle, 15 November 1913.

74 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich Colliery", Charles Cooper, District Surgeon to Magistrate Newcastle, 15 November 1913.

75 BL, BP2/2 (20), Dispatches on Indians in South Africa, Inspector of Prisons, Pietermaritzburg, to Director of Prisons, 30 November 1913, pp 12-13.

76 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich Colliery", Testimony of Duseph, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 12 December 1913.

77 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich Colliery", Testimony of Annamalay, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 22 November 1913.

78 Indian Opinion, 24 December 1913.

79 BL, BP2/2 (20), Dispatches on Indians in South Africa, Inspector of Prisons, Pietermaritzburg, to Director of Prisons, 30 November 1913, pp 12-13.

80 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Lellie Channie, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 3 December 1913.

81 NAD, PMB, AG 764/1913, "Alleged Floggings of Indians at Ballengeich", Testimony of Lellie Channie, Magistrate's Office, Newcastle, 3 December 1913.

APPENDICES and TABLES

(Author's note: these are reproduced verbatim from the original sources)

Appendix 1:

Statements made by Indian strikers (from Pietermaritzburg) at the Durban Gaol, 2 December 1913 before the chief magistrate, Durban with regard to their treatment at the gaol.

Rowashanker (questioned by the chief magistrate)

Q. Is this a sample of the ration which was given you to-day?

A. Yes, Sir

Q. You refuse to eat it?

A. I refuse to eat it.

Q. Why?

A. I desire to have certain things, and as soon as I get those things, I will eat it.

Q. What are the things you desire?

A. I want a pair of boots and socks. I want sandals. My coat is dirty, and I want a clean

coat. I wish to be among other prisoners who came from Pietermaritzburg.

Q. What complaint have you against the food?

A. I cannot partake of the food till I get the things I desire.

Q. (Indicating the food on the table) Will you eat this food?

A. No, sir.

Q. Have you any complaint against the food?

A. We did not intend to complain against this food?

Q. Where were you before you came here?

A. We were at school.

Q. What school?

A. Mr Gandhi's school at Phoenix Q. Did you wear shoes at school?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you wear them every day?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you always have clean clothes - clothes cleaner than those you have on now? A. Yes. I wear plain clothes, but they are clean.

Q. The food which you refuse to eat is the regulation allowance of rice, which I have myself tasted. It is well cooked, and good enough for my own use. There are also beans, which I have tasted, which are well and thoroughly cooked, besides boiled cabbage, eschalots, chilis, and an allowance of salt. Why do you decline to eat this

food?

A. I decline to eat it unless I am given clothes and sandals.

Bhaga (DG No. 4606/13) (questioned by the chief magistrate)

Q. What are your reasons for not eating your food?

A. I want sandals, socks, and salt.

Q. But salt is provided in your meals.

A. I want salt to clean my teeth in the mornings.

Q. What are the things you say you require, before you will eat this food?

A. I want sandals, socks and salt. (C.M. For your cleaning your teeth? Ans. Yes, sir.) I

also want a book to read, and a belt for my waist. I do not remember the other

things. Q. What do you do? A. I am a student in Johannesburg Q. What are you doing in Natal? A. I am put in gaol. Q. Do you wear sandals every day? A. I am in the habit of wearing boots.

Naganbhai (DG No. 4525/13)

Q. What are your reasons for not eating this food?

A. My little wants are not supplied.

Q. What are your wants?

A. Socks and sandals

Q. What fault have you to find with the food you have been supplied with?

A. I do not want to eat it until my wants have been supplied.

Source: BL, BP2/2 (20), Dispatches on Indians in South Africa, Inspector of Prisons, Pietermaritzburg, to Director of Prisons, 30 November 1913, pp 12-13.