Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Historia

versión On-line ISSN 2309-8392

versión impresa ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.64 no.1 Durban may. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8392/2019/v64n1a6

ARTICLES

Land and agrarian policy in colonial Zimbabwe: Re-ordering of African society and development in Sanyati, 1950-1966

Mark Nyandoro*

Senior lecturer in the Department of Economic History, University of Zimbabwe, a member of CuDyWat in the School of Basic Sciences at NWU (Vaal Triangle Campus) and extraordinary professor of research in the School of Social Sciences (subject group, History), Faculty of Humanities, NWU, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In 1950, Africans residing on the Rhodesdale Estate were forcibly evicted from designated Crown Land under the Native Land Husbandry Act by the Rhodesian state and were resettled in the Sanyati communal lands, then known as "native reserves". Eviction and resettlement were part of the re-ordering of African agricultural settlement and development to pave the way for white settler farmers in the Rhodesdale Estate following white migration to Rhodesia in the aftermath of the First World War. This reorganisation was premised on modernisation theory. This article challenges the white-dominated state's notion of modernisation by arguing that far from uplifting the lives of rural Africans, the state, using its racially-oriented legislative machinery, was not altruistic but aimed to turn Rhodesia into a "white man's country" intolerant of African economic competition. Discriminatory legislation led to scuttling socio-economic differentiation and obstructing the emergence of an entrepreneurial class in Sanyati. By investigating the evictions and resettlement of people from 1950 to 1966, this article argues that alongside the grand theme of separate development adopted by the Rhodesian settler state, there was an equally significant theme of African economic struggle to resist their marginalisation and impoverishment. The article provides historical data on livelihoods, migration and the impact of legislation, and demonstrates that colonial legislation in Southern Rhodesia stimulated the white-dominated economy through state support. It further argues that the intersection between state-promoted agricultural development, land allocation and the legislative requirements directing or prescribing standards for the separate development of Africans and whites, not only illustrates the generic growth of Sanyati, but also the historic evolution of a largely cotton-based economy which stimulated significant forms of rural differentiation in this region.

Keywords: Rhodesdale; Crown Land; Sanyati; forced evictions; migration; land resettlement; agricultural development; madiro; socio-economic differentiation.

OPSOMMING

In 1950 het die Rhodesiese Staat Afrikane wat op kroongrond in die Rhodesdale Estate gewoon het, gedwing om te trek na gemene grond in Sanyati, tóé bekend as "naturelle reservate". Dit het in terme van die Native Land Husbandry Act" plaasgevind. Uitsetting en hervestiging het deel gevorm van die herorganisering van Afrikane se landbounedersetting ten einde plek te maakvir blanke setlaarboere in die Rhodesdale Estate ná die emigrasie van blankes na Rhodesië in die naloop van die Tweede Wêreldoorlog. Hierdie herorganisasie het berus op moderniseringsteorie. Dié artikel daag die blank-gedomineerde staat se opvatting van modernisering uit deur te argumenteer dat, in plaas van die lewe van plattelandse Afrikane op te hef, dit nie altruïsties was nie, maar eerder daarop gemik was om Rhodesië te verander in 'n "witmansland" wat onverdraagsaam was vir die ekonomiese kompetisie van Afrikane. Dit is bereik deur die gebruik van die rassig-georiënteerde wetgewing. Diskrimenerende wetgewing het gelei tot wegloop sosio-ekonomiese differensiëring en die belemmering van die ontstaan van 'n ondernemersklas in Sanyati. Deur 'n ondersoek na die uitsetting en hervestiging van mense tussen 1950 en 1966, argumenteer hierdie artikel dat tesame met die oorhoofse tema van aparte ontwikkeling wat die Rhodesiese setlaarstaat aangeneem het, daar ook 'n ewe belangrike tema was in die ekonomiese stryd van Afrikane teen hul marginalisasie en verarmering. Dié artikel verskaf historiese data oor lewensonderhoud, migrasie en die impak van wetgewing; en demonstreer dat koloniale wetgeweing in suidelike Rhodesië die blank-gedomineerde ekonomie gestimuleer het deur staatsondersteuning. Verder word daar geargumenteer dat die wisselwerking tussen staatsgepromoveerde landbou-ontwikkeling, grondtoekenning en die wetlike vereistes wat die aparte ontwikkeling van Afrikane en blankes gerig het, nie slegs die algemene groei van Sanyati illustreer nie, maar ook die historiese evolusie van die hoofsaaklik-katoengebaseerde ekonomie wat beduidende vorme van plattelandse differensiëring in hierdie streek gestimuleer het.

Sleutelwoorde: Rhodesdale; kroongrond; Sanyati; wetgewing; gedwonge verskuiwings; migrasie; grondverskuiwings; landbou-ontwikkeling; madiro; sosio-ekonomiese differensiëring.

Introduction

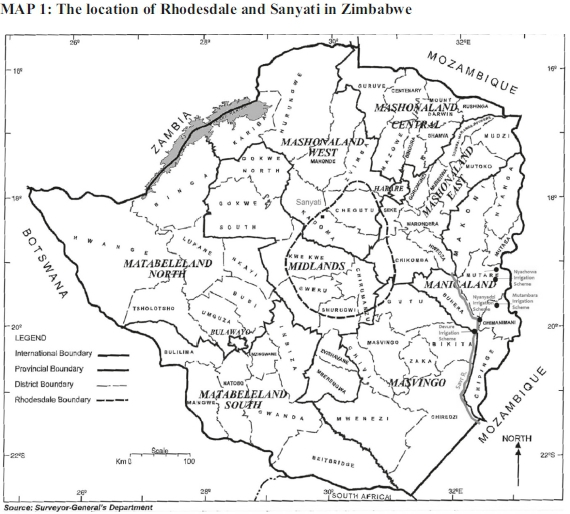

This article examines land and agrarian policy in colonial Zimbabwe and the reordering of African society and development in Sanyati (Mashonaland West Province] from 1950 to 1966. It contends that legislative foundations in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe] culminated in the compulsory eviction, migration and forced resettlement of African people from the Rhodesdale Estate to the Sanyati hinterland, approximately 100 km from Gatooma (now Kadoma]. The Rhodesdale Estate in the Midlands Province of Zimbabwe (see Map 1] was bounded by a line roughly connecting Gwelo (now Gweru], Que Que (Kwekwe], Hartley (Chegutu], Enkeldoorn (Chivhu), Umvuma (Mvuma), Lalapansi (Lalapanzi) and Gutu.1 Most of the people who were moved to Sanyati and Sebungwe (now Gokwe district) during the 1950s came from Rhodesdale, a vast ranch owned by the British multinational company, Lonrho Mining Limited, abbreviated as LONRHO.

The colonial occupation of Zimbabwe by the British in 1890 witnessed the advent of early forms of legislation under which land was expropriated from Africans in favour of the new European settlers. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, important pieces of legislation incorporated the 1894 Matabeleland Order in Council, the 1898 Southern Rhodesia Order in Council, and the seminal state case of 1918 in which the British Privy Council held that Africans had no title to land and that the land belonged to the British Crown. Following this and during the period of responsible government in Rhodesia - from the end of British South Africa Company (BSAC) rule in 1923 to the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in 1965 - a self-governing colony of Britain which was representative of the white population, was implemented. Because the hoped-for mining potential of the region had failed to materialise, agriculture became the country's dominant enterprise and principal export earner. To this end, white settler farmers who controlled much of this key sector and enjoyed a correspondingly dominant political importance in contrast to the peasant or African smallholder farmer, canvassed for a segregationist and discriminatory political and economic system which ensured that they enjoyed all the best that the country could offer and that their quest for building a "white man's country" could not be obstructed.2

After 1925, the system was supported by additional legislation, beginning with the passage of the Land Apportionment Act (LAA) in 1930/31. This act required that Africans residing outside the then Tribal Trust Lands (TTLs) or "native reserves" (now called communal areas), on alienated land and Crown Land designated as European land, forest areas and unassigned areas,3 were required to relocate. Land apportionment legalised the division of the country's land resources between black and white.4 This marked a major turning point in colonial Zimbabwe's racialised regime which in all respects became highly segregationist in outlook and disadvantaged Africans. As a result, to Africans, the LAA became one of the most hated symbols of white authoritarianism and exclusiveness.5

In the aftermath of the LAA, the commission on Native Production and Trade (under the chairmanship of Godlonton) was set up in 1944.6 The commission deemed it necessary to formulate a sweeping programme of "native" (African) improvement that was institutionalised by the Native Land Husbandry Act (NLHA) of 1950/51.7

The prescriptions formulated by this commission were explicitly framed by a larger thesis on natural law and development, one intended to put in proper perspective "the relative obligations of the European and African races".8 For the members of the Godlonton Commission, the displacement of African occupants from the land by Europeans was justified in terms of the "natural laws which inexorably govern human existence" to which Africans had either to adapt or else face extinction.9 As Holleman astutely observes, in this fashion, the commission

... reconstituted the Rhodesian social order as a product of the law of nature ... Europeans thus being identified with progress and progress being enshrined in an inexorable law of nature, the legitimacy of white progressive leadership now fully sanctioned by law and logic.10

Linked to the commissioners' desire to displace Africans from their original lands was the idea to use the NLHA to resettle people who were moved from white-designated areas in 1950. The NLHA was an agrarian revolution designed to reduce the carrying capacity of the land. Essentially, it was an attempt to attack the multifarious problems of erosion, land fragmentation and customary tenure, migratory labour and African agricultural traditions. It sought to foil the emergence of wealthy African farmers prior to and after their departure from the LONRHO Estate to Sanyati.

The place of departure of the evictees reveals evidence for their livelihood. Rhodesdale was situated in the Highveld which is the best agricultural region of the country with an ideal climate and rich soils suitable for the cultivation of a variety of marketable crops and livestock ranching. The estate was home to a number of local Africans, former migrant workers from Nyasaland (now Malawi), Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique) who had resided there for years as labour and rent-paying tenants who were to a certain degree allowed to practice some crop cultivation and livestock rearing. Before their eviction, they lived in Rhodesdale's so-called squatter communities following their transformation from African tenants to "squatters" by the Second World War. Most of the residents of Rhodesdale were relatively well off. They were economically successful entrepreneurs because of the resilience of their economy in the face of the colonial onslaught, entailing forced destocking and colonial labour demands which they staunchly resisted.11 Most of them possessed master farmer certificates and had an excellent farming record. Nyambara's informants described the lives of Rhodesdale tenants living on Crown Land prior to eviction in glowing terms. The area had abundant fertile land and most tenants owned large herds of stock that provided draught power and enabled them to fulfil many of their socio-economic obligations. The majority of former tenants of Rhodesdale, particularly those who had become successful black farmers, portrayed the estate as "a wonderful place".12

The tenants were therefore highly reluctant to enter into labour agreements with European farm-owners because the indigenous farmers had become agrarian entrepreneurs in their own right. In response to this rapid proliferation of "reserve" entrepreneurs in Rhodesdale, where Africans had become quite wealthy through increased agricultural productivity and the cultivation of relatively large 40-acre pieces of land,13 the enactment of the NLHA meant the intensification of government demands to reduce the size of land and the number of cattle that Africans owned.14The removal of Africans from Rhodesdale and similar areas to pave the way for whites already residing in Rhodesia and incoming-European immigrants15 thus became a paramount policy issue after the passage of the NLHA.

The racial system that emerged was characterised by political, social, economic and cultural domination of the black majority by the Rhodesian white settler minority. This partly explains how a small white minority appropriated the right to determine the pace and direction of the nation's land and agrarian development at the expense of the people originally living on so-called Crown Lands. As white settlers arrogated to themselves the right to decide the agrarian, economic, social and political future of the country, the black people originally inhabiting Rhodesdale struggled to assert their rights over prime agricultural land and water -two very contentious natural resources in the history of Zimbabwe. The white-dominated government frequently called upon its formidable arsenal of repressive legislation, including the notorious LAA and the NLHA which it deployed liberally to facilitate the eviction of Africans from the best agricultural lands, a colonial creation by the LAA for the exclusive use of whites, who subsequently constituted the backbone of large-scale commercial farming in colonial and post-colonial Zimbabwe. Land legislation was employed by Rhodesians to entrench their political and economic power and to thwart African opposition in order, as argued by Holleman, to protect and defend so-called "civilised standards" which facilitated the whites' version of development and government.16

The purpose of this article is to examine land and agrarian policy in colonial Zimbabwe with particular focus on the NLHA's reordering of African society and development in Sanyati. Sanyati, like neighbouring Gokwe in the Midlands Province, was the major destination for the evicted "Rhodesdalites" from 1950 onwards. The study argues that development in the Sanyati communal lands in the years before and after massive evictions from Rhodesdale was firmly hinged on legislation which served clear political and economic purposes. It is submitted that colonial legislation after World War One prescribed ways of stimulating the white-dominated economy through state support and laws on industrial manufacturing, water resource development, mining enterprise, land and agricultural development. By exploring the intersection between state-promoted agricultural development, land allocation and the legislative requirements for the separate development of Africans and whites in the colony, a modernisation theory becomes clear. The colonial state aimed to stimulate the white-dominated economy on the basis of two paramount settler policies - the LAA and the NLHA. These laid down the agricultural planning, growth and control it envisaged by sanctioning African evictions to Sanyati. Africans who prior to 1950 resided in Rhodesdale were forcibly evicted under the stipulations of the NLHA.

The article analyses major trends between 1950 and 1966 in the eviction and eventual settlement of the "Rhodesdalites" in Sanyati - an area already settled by original or indigenous Shona-Karanga inhabitants, derogatorily termed Shangwe by the "incomers". The Shangwe of Chief Neuso, in turn, disparagingly described the incoming "immigrants" under Chief Wozhele as Madheruka.17The historical relationships between "incomers" and autochthons in Sanyati, epitomising recognition and assertion of their differences, have been characterised by tension between the Shangwe and Madheruka which was informed by Rhodesian-era evictions and resettlements.18 This sets the context to investigate how agricultural development in the new settlement was achieved in the pre-irrigation era. Because irrigation, which commenced with the inception of the Gowe-Sanyati Smallholder Pilot Irrigation Scheme along the Umnyati (now Munyati] River in 1967, was characterised by different land and agrarian dynamics, this justifies ending the study in 1966.

Among the questions the article aims to answer are: How were the Rhodesdale evictions carried out? What was the nature of migration from Rhodesdale to Sanyati and the process of forced resettlement? What was the state of African (Shangwe) farming prior to 1950? How important were "immigrants" (Madheruka) to the agrarian development and emergence of socio-economic differentiation in Sanyati between 1950 and 1966? What role did the "immigrants" and the state play in facilitating the growth and development of the area during this period? Answers to these and related questions and the interface between the state and farmers, sheds light on this important topic in Zimbabwe's colonial past which has hitherto received little scholarly attention.

Historiography

Studies on land and racial discrimination in colonial Zimbabwe have been conducted by several scholars such as Palmer, Machingaidze, Phimister, Moyo, and Nyandoro.19These studies have established a link between the two major pieces of colonial legislation, the LAA and the NLHA. They also analyse the evolution and development of Rhodesian agriculture and colonial conflicts over land, but with the exception of the work by Nyandoro,20 they do not explore the interface between these laws, other regulatory measures and forced migration to the remote, land-scarce, diseased and wild animal-infested Sanyati region of the country in the pre-irrigation phase. Moreover, although these studies focus on racial struggles over prime farmland, state-induced land-use patterns, technical development and peasant impoverishment, they neglect to investigate how the central government's preoccupation with different forms of legislation led to forced migration, with major consequences. Amin addresses the politics of land in Zimbabwe and its state-making since independence in 1980,21 but an analysis of the intricate relationship between colonial land policy, migration and forced resettlement is not only glossed over, but is not the primary focus. This current article engages with the wider literature to add a fresh dimension to existing knowledge on migration, settlement and agrarian development on the basis of a rural micro study.

Scholarship that contextualises evictions, resettlement of people, pre- and post-independence agricultural development and rural differentiation has been produced by Worby and Nyambara. They focus on land acquisition and cotton labour dynamics in Gokwe (a district close to Sanyati) by arguing that most rural areas experienced considerable commercialisation during and after the colonial period, and that this gave rise to various forms of socio-economic differentiation among rural households and communities.22 Their studies advance various arguments about how socio-economic differentiation occurred in rural Zimbabwe. Worby, on the basis of a study of the small dryland (rainfed) farming village of Tazivana in Goredema Ward (Gokwe), which he uses as his springboard, examines relations of power, labour and identity in time and social space. The central focus of Nyambara's study is the role of differential access to land resources in the broader context of socio-economic differentiation in the communal areas of Gokwe. Both Worby and Nyambara point to differences in access to land between freehold and communal areas and within communal areas; differences in households' access to farm and off-farm income; the privileged position and political manoeuvrings of chiefs; the variance in the quality of land and differential access to labour.23 Besides these studies, important light is shed on rural differentiation by Masst who analyses how the maize/cotton commodity boom influenced forms of class inequality, stratification and socio-economic differentiation among peasants in post-independence Zimbabwe. However, while there are some overlaps with my current study, especially on forced evictions and socio-economic differentiation, none of these works focus on Sanyati which, unlike land-abundant Gokwe, was characterised by shortages of land for the incoming "immigrants" from Rhodesdale. Sanyati had its own unique forms of differentiation.

Four features make Sanyati, unique in the history of colonial development. Most distinct is its perceived marginality in terms of distance from historical centres of missionisation, economic growth, population concentration and political power. Catholic and Baptist missions, for example, were only established in the Sanyati-Gokwe region between 1954 and 1963, and the construction of government schools only began in the late 1970s before increasing rapidly after Zimbabwe's independence in 1980. Second, before the advent of irrigation, settler reaction to drought in an area of limited average rainfall mainly involved the distribution of food relief. But, more importantly, settler reaction to rainfall deficiencies entailed encouraging peasant farmers to grow drought-resilient crops such as cotton, mhunga and sorghum. This was confirmed by W.D.R. Baker, the provincial commissioner for Mashonaland South, when he stated: "A marked swing to drought resistant crops is expected [in the fight to alleviate hunger in the rural areas]".24 Third, the region is distinguished by the historical absence of competing land claims by European settlers. For Worby, the significance of the region's late incorporation into the overall pattern of colonial state-making for its future position in the post-colonial national development regime, is in no doubt.25 A malarial, tsetse-infested lowland with patchy and variable rains, white farmers considered it unsuitable for crop cultivation or animal husbandry. Until the 1940s, the economy of the region consisted of a combination of subsistence agriculture and pastoral pursuits. To some degree, the people of Sanyati gathered fruits and hunted animals that were still abundant in the area. Subsistence farming sustained a meagre livelihood in the area which was demarcated for people who had originally lived on the Rhodesdale Estates who were targeted for forced resettlement to the sparsely populated frontier regions of Sanyati and Gokwe.26 Given a choice, Chief Wozhele and his people ("Madheruka") would not have opted to settle in this place. But the "arrival of development" in the region meant the forced resettlement of entire villages or chiefdoms in Sanyati and the resultant emergence of differentiation. This speaks to social integration in the recipient spaces.

It is startling how state attention was drawn and spread to regions like Sanyati, hitherto distinguished by the historical absence of competing claims by European settlers to land and considered to be unsuitable for crop cultivation or animal husbandry by whites. This article fills this gap by examining not only the avoidance of settlement in this region by whites, but how the policy of resettling the former "Rhodesdalites" led to African poverty and marginalisation. It also tries to determine how poverty and marginalisation engendered peasant initiative to amass wealth, with clear patterns of rural differentiation emerging in Sanyati following the mass evictions of people from Rhodesdale.

Migration and forced resettlement

How the evictions from Rhodesdale were carried out demonstrates the extent of force employed by the state to resettle African people. Migration from the Rhodesdale Estate and the process of forced resettlement in Sanyati was premised on the legal basis provided by the NLHA. Evictions were not taken lying down. They took place under a thick cloud of mobilised and spontaneous people-centred resistance. For instance, when Benjamin Burombo (affectionately known to his many nationalist supporters simply as B.B.), the organising secretary of the British African Workers' Voice Association (The Voice, in short) received the news of the impending eviction of the original paramount chief, Munyaka Wozhele, and his followers in 1950, he went to Rhodesdale and issued strong encouragement that the people should refuse and resistremoval.27

Burombo came into the political limelight in 1947 when he formed this association in Southern Rhodesia with its headquarters in Bulawayo. The association's chief aim was to unify Africans politically and to fight for better economic opportunities and social advancement. Supported by traditional chiefs and their people,28 Burombo's contribution marked the beginning of full-scale resistance to forced removals. Much as B.B. might not have countenanced it, the whites prevailed upon Chief Wozhele to go on a preliminary inspection of Sanyati "Reserve". He was not pleased with what he saw during reconnaissance because the area was infested with tsetse flies and mosquitos. It resembled a jungle and prior to various interventions was characterised by dense forest and was inhabited by dangerous wild animals such as elephants, lions, hyenas and poisonous snakes. Nevertheless, despite stubborn resistance by his people against forced removal from Rhodesdale, Wozhele was still compelled to settle there.

Notwithstanding the stiff resistance to move to this inhospitable backwater of the country, the chief's inspection trip was immediately followed by a decisive meeting at Elephant Hill (Chomureza Hill) between the native commissioner (NC) of Gatooma, a man called Finnis, and Que Que's new NC, Buckley. This meeting, which was attended by Wozhele, signalled confirmation of his removal together with his people, including Headman Mudzingwa, to Sanyati despite Burombo's efforts of "zuva ravira" (the sun has set), which tactics Burombo employed, through the medium of The Voice to mobilise people to denounce settler colonialism.29 The term signified that "the sun had set" or there was no going back. It was coined by B.B. and the Rhodesdale evictees to mean that the time had come to fight and resist unjust colonial prescriptions such as the forced removal ofAfricans.30

But the die had been cast and the first wave of "immigrants" was forcibly moved to Sanyati in 1950. This year marked the beginning of repressive fast-track removals and acts of arson of unprecedented magnitude for most of the people living on the alienated and crown lands. The date of 11 December 1950 was the deadline set by the so-called Native Department31 for the final evacuation of people residing on the Rhodesdale Estate.32 The colonial government used its administrative officials, the Rhodesian police force and the military to evict people from Rhodesdale to Sanyati between 1950 and 1953. The eviction process was conducted in phases.

The first group was moved forcibly to Sanyati in 1950 when the coercive and insensitive model of development was reaching its apogee in the passage of the NLHA. The second came in 1951, and the third and last wave took place in 1953. In a show of excessive force, the Rhodesdale residents were loaded onto waiting trucks (Thames Trader and Bedford lorries) "family by family", in groups of 10 to 12 families at a time. They were given only short notice and were transported into the inhospitably hot Sanyati and Sebungwe districts. The human targets of these calculations recall that they were "chased away" from their homes in Rhodesdale because whites wanted to farm there. Their huts were razed to the ground to compel them to move out of Rhodesdale. Recounting just how forcefully they were evicted, Anna Madzorera (Kesiya Madzorera's wife) said:

... the government forced us to leave Roseday [sic]. They sent the police with big lorries and they forced us into lorries and brought us to Nyaje. They had to force us as we had not agreed to move to a place we did not know. We lost a lot of property in the process because the police just threw our things into trucks. They were very rough.33

Similarly, a nationalist leader, Temba Moyo, a former member of the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), narrated the Rhodesdale evictees' ordeal as follows:

On our way [home] many police trucks raced past us. When we arrived my uncle told us that the Europeans had just arrested the chief, because he told the people to resist. A police truck sped out of the village and we could see the chief and some elders handcuffed and under guard ... Later that day soldiers and police started ordering men to empty their houses and barns. When they refused they were arrested. Soldiers entered their houses and threw everything onto trucks, wrecking a lot of things in the process. Then they did the same with the barns, loading all the tools, grain, etc. into the same trucks. This over, the women, children and old people were put on top of their belongings and driven away. The animals had been rounded up and the boys were ordered to drive the herds north. It was a sorry sight - women, children, old people were weeping, the men arrested, homes set on fire and destroyed.34

Such traumatic experiences had fatal consequences as the case of Chief Wozhele illustrates. Just before the second wave of "immigrants" was dispatched to Sanyati in 1951, Chief Munyaka Wozhele died. One informant in Sanyati narrated a deeply touching story of the palpable pain, agony and anguish that accompanied these forced evictions. Joke Munyaka Wozhele who alleges that the late chief was his grandfather, explained:

The trauma caused by eviction from Rhodesdale led to my grandfather's death. My grandfather was a High Blood Pressure (BP) patient, and was one of the staunchest opponents of eviction from Rhodesdale. He could not stomach the damage inflicted on his property [acquired from many years of hard work] during the process of eviction. As he helplessly watched the proceedings [which entailed hauling and wrecking his possessions onto the lorries waiting to take them to Sanyati] he crumbled under the weight of this pressure, collapsed and died on 9 August 1951. He must have suffered a sudden and severe stroke.35

Apparently, unperturbed by this tragedy, the whites insisted that the African people, together with the relatives of the hypertension victim, should depart for Sanyati. Under an acting chief whom Wozhele had appointed with effect from 1 September 1951, they were moved to the "reserve". Thus, migration from Rhodesdale to Sanyati was characterised by brute force, particularly for those who offered stiff resistance under the influence of B.B. Evidently, the colonial land and agrarian history of Sanyati in Zimbabwe can as much be traced to the forced movement of people originally living on alienated and crown lands, as to their settlement in the inhospitable Sanyati in the aftermath of the evictions.

Land, agrarian development and settlement of immigrants

In the aftermath of the Rhodesdale evictions, Sanyati has been inhabited by an assortment of both indigenous (Shangwe) and "immigrant" populations (Madheruka) who fell and still fall under paramount chiefs Neuso and Wozhele respectively. The area designated for the Rhodesdale evictees had already been determined prior to the final settlement by Whozhele's people. At a meeting held by members of the Native Department in September 1950, it was decided that "all families ... moved from Rhodesdale would by force of circumstance be accommodated in the areas mentioned even if the size of what was regarded [under the NLHA] as an economic unit had to be reduced".36 At the national level, the Act came up with stipulated allocations of land and stock - in line with what was deemed to be the carrying capacity of an area.37 A "standard area" or "economic unit" of land was allocated per family unit (comprising a man, his wife and three children) by the NC under the direction of the chief native commissioner (CNC) as primary allocative authorities, thus effectively usurping the right to allocate land by traditional chiefs. An "economic unit" was defined by the architects of the Act as:

... a piece of land which, if farmed according to recommended procedures laid down by the Department of Native Agriculture, would serve not only to support the holder and his family at subsistence level, but was expected to be capable of producing a crop surplus for sale.38

The size of the "standard unit" was fixed according to the climatic and ecological configuration of each area. In high-rainfall regions the standard holding was six acres, ranging to as much as 15 acres in the driest areas. Ideally, a holding in the 28-inch rainfall area would have eight acres of cultivable land with the producer/farmer's stock requiring ten acres of grazing land per animal unit. The position adopted by the NLHA, according to Ian Smith, was an attempt to introduce so-called modern cropping methods or scientific farming, for example, "green cropping, crop rotation and the use of legumes [as well as manure and artificial fertilisers]".39 This stipulation in the Act was aimed at intensifying agricultural production by changing what was perceived to be the haphazard system of "shifting" cultivation (referred to as "slash-and-burn" agriculture or chitemene in parts of Northern Zambia) of the pre-colonial period, to one more suited to a sedentary type of agriculture.40

The area set aside for habitation by those families that were relocated to Sanyati is prone to drought because it receives very little rainfall. Its ecosystem is typified by sparse vegetation and predominantly poor, infertile sandy soils as opposed to the rich alluvial soils of Rhodesdale, where domesticated animals such as donkeys, cattle, goats, sheep and other livestock were kept. In earlier times (before the settlement of the Rhodesdale evictees), animal husbandry in Sanyati had been rendered almost impossible by the presence of tsetse fly but by 1950, tsetse control campaigns had registered significant success. However, the area was largely inhospitable due to the prevalence of disease and was home to a variety of wild animals. Crop cultivation in such an environment was associated with a considerable amount of risk. It was here, however, that the "immigrants" dislodged from Rhodesdale were allocated land under the NLHA.

Records from the work of the officers in charge of resettlement in Sanyati reveal a preoccupation with the practical exigencies of getting boreholes drilled, roads made, dip tanks set up and administrative buildings constructed. Because they were settling the evicted people, colonial officers were also obsessed with ridding the area of tsetse fly. Among the first evictees of Rhodesdale were between 356 and 470 families under the newly installed Chief Wozhele and his headmen, Mudzingwa and Lozane, who were accommodated in the 28 000 hectare Sanyati Reserve, each with a maximum allocation of eight acres of arable land and ten head of cattle.41 However, according to the land development officers (LDOs)42 reports, by 1950/51 the exact number of cattle belonging to the new settlers who had been moved from Rhodesdale to Sanyati was unknown,43 although some farmers had already sold maize for cash and a total of 1 083 and 571 people in the Neuso and Wozhele chieftainships respectively, were taxpayers by 1966.44 Another group consisted of 1 000 families administered under the headmen Myambi and Chirima, who were forcibly settled in the Gokwe "Special Native Area".45 This colonial administrative system, which was applied to African areas, illustrates that most of the early "immigrants" were settled in rural villages with small land allocations under their own village heads and headmen, but formally under the ultimate jurisdiction of indigenous chiefs. In Sanyati, the settlement of the "reserve" by "immigrants" which commenced in 1950 continued up to the 1960s, but ended earlier there compared to Gokwe. According to the NC of Gatooma, G.A. Barlow, new land allocations were terminated between 1960 and 1961, and by 1963 some 113 000 people had been forcibly relocated throughout Southern Rhodesia, and "immigration" to Sanyati faded to a mere trickle of the relatives of those already resettled there.46

It soon became clear that the evictees from Rhodesdale who were settled in Sanyati, were doomed to suffer the displeasures and fears predicted by the late Wozhele when he made his reconnaissance visit. The area's well-documented ecological vulnerabilities were not its only challenges in the aftermath of the forced resettlements. There was hardly any decent infrastructure by way of roads, bridges, schools, stores, grinding mills or reliable water sources. Perhaps the most noticeable service that was provided by the government was a rudimentary road infrastructure to facilitate travel and administration by the NC or the district commissioner (DC). The only distinguishable human inhabitants of the area at that time, the people of Chief Neuso, lived in one line (raini in Shona) in the middle of this thick bush. Evidently, during the process of forced resettlement, Africans were not given a choice to decide on their final destination following eviction. Without considering the suitability for human habitation, the recipient areas for the migrants were determined by the government which appointed various colonial officials as administrators. Agricultural demonstrators and land development officers were among the colonial officials appointed in the pre-and post-settlement eras; not only to facilitate the administrative process, but to establish state-approved farming systems and to provide essential agricultural extension advice to the newcomers. The state clearly used the NLHA as an important piece of colonial legislation to justify its actions and interventions in the agrarian development of the newly resettled area. State actions in Sanyati, however, did not proscribe the process of differentiation and the growing accumulation tastes among the newly settled peasant farmers.

Rural differentiation defies NLHA dictates in Sanyati

Development and differentiation were fostered in Sanyati despite the purported impact of the NLHA. Rural differentiation refers to the economic, political, cultural and normatively defined relations that underlie the construction of social categories.47 It emphasises, inter alia, households' scope for economic manoeuvre, and is used to measure economic stratification among the peasantry. It defines who occupies the lowest, middle or highest strata of the peasantry or commands economic resources more than the other.48 The socio-economic differentiation that emerged in Sanyati in the aftermath of the evictions, as in Gokwe, was premised on cotton cultivation. The growing of cotton by peasant farmers was part of a sanctions-busting measure to boost textiles and exports during UDI - a turbulent phase characterised by economic and political instability and the need to keep an economy under siege from United Nations (UN)-imposed sanctions afloat.

Climatic conditions and, particularly, Sanyati's limited amount of average rainfall also influenced the colonial government's choice of a commercial crop in the drought-ravaged Sanyati communal lands. Since the 1960s, the growing of cotton (a drought-resilient cash crop) was encouraged and cotton introduced an element of commercialisation in the region. Confirmation of government awareness of the vagaries of the weather was illustrated when cotton was introduced to the Sanyati-Gokwe region in 1963 by the agronomist in the Extension Department, Melville G. Reid, following the cotton-based extension programmes he implemented in the area.49 So-called demonstrators and chiefs (who were appointed by the administration), together with compliant religious leaders, were tasked with the responsibility of persuading and convincing ordinary people to accept the rationale for cotton cultivation in suitable districts like Sanyati. This was an example of using agriculture as a poverty-reduction strategy and by 1966 cotton became a prosperous crop with some farmers realising yields in excess of 1 094 lbs per annum.50 Since 1963 maize and other crops were also grown, but cotton had become the chief crop.

Cotton commodity production by smallholder rural farmers led to the creation of different social categories - mainly comprised of relatively rich and poor peasants in Sanyati, depending on questions of land, labour, identity and the culture of modernity of the "immigrants" from Rhodesdale.51 In colonial Rhodesia, administrative officials regarded "immigrant" Madheruka master farmers as the embodiment of modernisation and progress because they had been exposed to forces of modernisation in their areas of origin, while both officials and "immigrants" alike regarded indigenous Shangwe as backward and primordial. The sequence and timing with which Sanyati received "immigrants" had important consequences for differentiation. The coming of "immigrants" from the Rhodesdale Estates into Sanyati, with their good knowledge of agricultural techniques, boosted and intensified the rural differentiation process. They were generally viewed as possessing greater agricultural intelligence than their Shangwe counterparts. However, both indigenous Shangwe and "immigrant" Madheruka cultivated small eight-acre pieces of land based on the allocations made by the colonial government under the NLHA.

Sanyati smallholder farmers were required by law to cultivate land of more or less the same size - a situation synonymous with egalitarian land holding. The idea was not to allow economic affluence and competition with whites. Thus the state, through the enforcement of strict racist land-alienation procedures, was reluctant to promote the emergence of a wealthy African class thereby authenticating the claim by a large body of scholarly work that Africans in settler colonies were economically marginalised as an intended consequence of colonial policies.52 As Cowen has suggested in another context, the aim of such state measures was to generate the development of an undifferentiated middle peasantry, producing high-grade export crops (cotton in the case of Sanyati) under "controlled and increasingly technically advanced methods of production and to avoid the uncontrollable aspects of rich peasant differentiation".53 In Rhodesia, as in other global examples, this form of development of commodity production was preferred by international capital, yet obstructing any tendencies towards formation of an autonomous national bourgeoisie. The colonial state's interest in curbing rural differentiation in Rhodesia can be questioned in light of the fact that the 1930/31 LAA admits that the rise of an African rural bourgeois class was clearly inevitable. Yet it can be upheld for Sanyati because this Act only made provisions for successful African farmers to access more land in the African Purchase Areas (APAs) and not in the "reserves".54 APAs were also known as Native Purchase Areas (NPAs) or African Purchase Lands (APLs). Whatever accumulation of wealth that was experienced by the Sanyati peasantry and the rise of commercially-oriented rural Africans in the "reserves" were merely unintended consequences of state policy because the farmers had used their own initiative to accumulate wealth.

In response to growing rural differentiation, the state made concerted attempts to use the NLHA to reduce land sizes and the number of cattle. In spite of this requirement, recent research on the impact of the NLHA shows that a great number of "reserve" entrepreneurs managed to avoid having their fields and cattle herds reduced. According to Phimister, richer cultivators generally refused to comply with state directives to limit the size of land they could plough and the number of cattle they could own. Hence,

... a significant number managed to cling to [their] extensive plots which they continued to work more or less as they pleased ... Owners of large cattle herds also continued to enjoy some success in blunting the worst of the state's offensive.55

For Nyandoro, in Sanyati, generally well-off Madheruka and Shangwe employed various manoeuvrings to plough bigger pieces of land than prescribed by the state. Land ownership became unequal or disproportionate through social and political manoeuvrings by some dryland farmers and chiefs.56 By the 1960s, two distinct categories of farmers had emerged, that is, a small-scale subsistence crop cultivator group and a group of relatively large-scale producers of crops for sale to the Grain Marketing Board (GMB).57 Cattle ownership throughout the country also became more unequal, as demonstrated by Le Roux's assertion that, "as with crops two types of cattle owner[s] had developed by 1960. One was a small-scale owner with a subsistence herd; the other was a large-scale owner who supplied the beef market".58In this way, dryland agriculture was manipulated by different groups within the Sanyati community to manoeuvre their way to relatively higher social positions with crops and cattle determining patterns of rural differentiation in the region, thereby confirming the validity of the arguments of Cousins et al. and Worby, which deconstruct the legal fiction that households in the communal areas were essentially as alike as peas in a pod.59 Sanyati farmers, apart from being perceived as homogeneously poor, were not alike but were differentiated. In many instances, the impoverished and marginalised position of the peasantry did not preclude the emergence of rural differentiation as attested to by the practical experiences of the farmers.

The rapid commercialisation of agriculture and differential access to land, cattle and labour,60 shaped people's strategies for economic ascendancy. Dryland agriculture became a means of differentiating people. As stated, after the forced resettlement exercise several families were accommodated in the Sanyati communal lands, each with a specific allocation of arable land and head of cattle.61 Nevertheless, due to various forms of manoeuvrings, some farmers came to own larger pieces of land and larger herds of cattle than their counterparts. Freedom ploughing - the unilateral right peasants gave themselves to cultivate wherever they wanted - was one such manoeuvring and it was quite widespread in Madiro (also known as Kufa or Chomupinyi) Village (Ward 23) headed by Morgan Gazi. The village was given this name because of the massive land-grabbing that went on in defiance of NLHA stipulations. Most "reserve" entrepreneurs in Madiro Village cultivated up to 15 acres. Headman Gazi says, because he was a nephew of Chief Wozhele, he cultivated about 18 acres,62 ten acres more than the standard allocation, illustrating how rife and uncontrollable madiro ploughing was, especially among people with chiefly connections.

Just as the ownership of expansive pieces of land was prohibited, the accumulation of cattle by "reserve entrepreneurs" was also forbidden. A ring or grazing permit which was issued in terms of Section 9(2)of the NLHA entitled people to keep a maximum of 10 to 20 head of cattle, but some enterprising peasants like Morgan Gazi's uncle, Phillip Gazi, falsely declared in 1952 that he had ten head of cattle when in actual fact he had two. Under-declaring, and in this case over-declaring gave him the leeway to increase his cattle herd later to a maximum of ten, thereby making a mockery of the NLHA's checks and balances at the peak of destocking measures. As a dip tank officer at the time, responsible for the dipping and counting of all stock in preparation for destocking63 (a portfolio he held up to 1970 when he was promoted to become a dip supervisor until 1992), Morgan Gazi did not reveal this over-declaration to the white officials. Phillip Gazi, as a result, was issued with a grazing permit for the ten head of cattle he purportedly held. Clearly, this was made possible with the connivance of his cousin who used his position to access more land and to help conceal the number of newly-born calves to protect other "reserve" entrepreneurs and kinsmen from destocking, thereby helping to blunt the state's offensive. Differential land and livestock holdings therefore illustrate that for the most part, the state failed to eliminate social differentiation in the rural areas.

Despite the plain demonstration by Sanyati dryland farmers that their allotted pieces of land were small and sub-economic, white officials were reluctant to allocate more. Instead, they blamed land degradation and erosion on the farmers but not on the overcrowded conditions which the state had created by concentrating human and animal populations in a small area. Overpopulation thus partly explains why the local agricultural development staff was tasked with the responsibility of enforcing conservation and extension measures. This was a by-product of concern expressed in official circles through the Natural Resources Act about the state and extent of land degradation in the rural areas in general. According to Phimister, in 1954, the Natural Resources Board [NRB) had expressed alarm, if not despondence, at the extent and rate of soil erosion in the so-called reserves:

The time for plain speaking has now arrived, and it is no exaggeration to say that at the moment we are heading for disaster. We have on the one hand a rapid increase taking place in the African population and on the other a rapid deterioration of the very land on which these people depend for their existence and upon which so much of the future prosperity of the country depends ... the happenings in the Native reserves must be viewed in the light of an emergency and not as a matter that can be rectified when times improve, for by then the opportunity to reclaim will have passed.64

What was ignored was that in the dryland, the eight-acre pieces of land allocated to Sanyati residents were too small to facilitate accumulation and to cater for the increase in both the human and animal population. The small pieces of land had an impact on the dryland farmers' skills in two major ways. Firstly, because some landholders had master farmer certification, given their farming expertise this was an avenue towards intensified agriculture. Secondly, most of them strove to succeed on the small dryland plots which, as in the case of Norman Savata Gwacha of Kusi Village [Chief Wozhele's area), were sometimes extended to ten acres or more,65 and the livelihood outcomes in the first five years and later years of settlement were quite impressive. They were able to subsist from agriculture as well as generate a surplus for sale from a commercial commodity crop like cotton. Job Gwacha, brother to Norman, spoke of their family's prosperity which was derived from expanded cotton cultivation in the dryland and irrigated area [after 1967) at Gowe-Sanyati. He confessed that besides his 60-strong head of cattle, part of which he sold to pay school fees for his children,66 from the 1960s to the 1970s the major crop that gave farmers, including his brother, much profit was cotton. He pointed out, as corroborated by Norman, that they grew the Alba cotton seed variety which fetched a good price. For him, without indicating the exact size of his yield and the extent of his profit, "the price of cotton [of 8 pence per pound] was very lucrative".67 In the season just after 1966, Norman confirmed that he produced 50 bags of maize and eight bales of cotton, and his grade A maize and cotton were sold at the Grain Marketing Board and the Cotton Marketing Board (CMB), now the Cotton Company of Zimbabwe (COTTCO) in Gatooma at £1.2s.6d per bag and eight pence per pound respectively.68 The harvested and initial yields of cotton enabled some dryland peasants to apply for bigger farmland in the nearby NPAs of Copper Queen and Chenjiri where larger pieces were permitted. At the administrative level, the success of cotton was used to push for a tarred strip road system to Gatooma where cotton was mainly marketed before the establishment of the CMB depot at TILCOR Sanyati Growth Point in 1976. The Gatooma District Council argued that roads were of "national importance" and an integral part of the development of the region.

Although Sanyati's dryland regions experienced development based on cotton cultivation, overcrowding caused erosion. Erosion was seen by the farmers, who were bent on accumulation of wealth, as largely a reflection of the colonial government's oversight in allocating small pieces of land. In addition to the small tracts of land for each peasant household, conservation measures such as the construction of wide contour ridges [makandiwa] by the agricultural extension officers, to combat erosion, had the deleterious effect of reducing the size of land a farmer could put under the plough.69 According to the councillor for Ward 23, Jacob Mukwiza, a Jeep truck was actually driven through the contour to make sure that it measured up to the expected width.70 Gully erosion due to population and land pressure rendered large portions of land useless for production. Contouring was viewed by the colonial government as a panacea to the massive land degradation induced by surface run-off. As if this was not enough, the contour ridges, which the "immigrant" and local Shangwe cultivators were coerced to erect to address the problem, ate into their already small plots. This culminated in stiff resistance against conservationist policy in general and the NLHA in particular. In this case, erosion and not differential access to land was responsible for differential levels of production among the Sanyati peasants. To some extent, the erosion plague facilitated the development of significant disparities in agricultural income. Therefore, the role of erosion, conservation and extension measures, coupled with discriminatory laws, in enhancing land shortages and obstructing differentiation in the countryside cannot be overlooked. Indeed, in spite of the unfavourable political climate imposed by an authoritarian legislative structure, the 1950s and 1960s witnessed increased rural differentiation because peasant households with sufficient resources diversified their agricultural pursuits and took to cotton cultivation. Attempts by the state at obstructing any tendencies towards the formation of autonomous rural elites were thus rendered futile through resistance and blatant defiance of the NLHA.

Notwithstanding the NLHA, local entrepreneurs made concerted efforts to survive in the otherwise difficult Sanyati environment. Peasant differentiation continued unabated; rural elites were not destroyed by the Act, but they were some of the most vociferous opponents of the NLHA.71 This seems to contrast sharply with the belief that entrepreneurial peasants comprised only a tiny and dwindling minority of the inhabitants whose backs were broken by the NLHA's implementation, and whose protests were unimportant compared to those of the landless poor. Far from the Land Husbandry Act checking "entrepreneurial individualism",72 the "wealth gap between these two classes of farmer" actually increased during the 1950s,73 and continued to increase after 1963 with cotton commercialisation.

After 1961, new land allocations in Sanyati under the NLHA ceased.74Consequently, the general scarcity of land, together with forced adjustment to the contour regime, the increase in dipping fees (tax) and destocking measures (which forced farmers to under-declare stock numbers to escape destocking and dipping fees) fomented much discontent in the rural areas. Between 1961 and 1963, more people than merely the relatives of those already resettled in Sanyati continued to look for land as a critical wealth-enhancing resource. The NC of Gatooma (Barlow) actually complained that in the month of March 1961, he had been inundated with applications by Africans of other districts for permission to move to Sanyati.75 Barlow countered that: "[Land] allocation in Sanyati was completed last year [1960] apart from ... 1 600 acres which was block allocated and where individual allocation will be done this year [1961]".76 He continued:

The possibility of allocating extra people on consolidated holdings in the "Jesi" area is being investigated by Technical Block, but this is very much "in the air" and to all intents and purposes there is no more land available in Sanyati ... While it is difficult to refuse these applications and while I cannot quote any authority for my right to do so, nevertheless I am doubtful of the wisdom of allowing them in, since they will merely increase the number of landless people in the reserve and probably be a source of trouble in the future.77

The Jesi bush zone is a very dense thicket of approximately 15 000 acres in size, situated in the central part of Sanyati on white sandy soils. According to the Sanyati Technical Survey Report, its stocking situation was rather "on the heavy side" by 1954.78 Due to land shortage in the 1950s and 1960s, the manoeuvrings to access more land for crop cultivation persisted and many people were ploughing in the grazing areas to make up for the lack of land. They did so despite the threat of prosecution, even after the abandonment of the discriminatory NLHA in 1962 due mainly to African opposition. For encroaching onto the grazing lot, in 1964 the DC of Gatooma (Westcott) intimated that offenders would be charged under Section 42 of the African Affairs Act which empowered law-enforcement agents to prosecute them for disobeying the orders of the chiefs and headmen against this illegal practice.79 The law, nevertheless, proved difficult to enforce since some of these so-called kraal heads were themselves also ploughing in the grazing area. Complaints that "the grazing area [was] being completely taken up and that the cattle [were] dying of starvation" were frequently heard.80

Like their subjects, chiefs, members of the royal court and resident elders were determined to use their privileged position to retain their hold on large plots. Chief Ndaba Wozhele, for example, together with his royal lineage were not prepared to give up the practice of over-ploughing (madiro) because in Rhodesdale they cultivated fields of up to 40 acres which was five times the standard allocation in Sanyati. In an interview, he confessed that "people disliked the NLHA because they were used previously to a life of no control".81 Despite the strictures imposed by the Act, Wozhele and his kinship group, Mudzingwa, Tiki, Vere, Sifo, Ngazimbi and Mazivanhanga clung on to their abnormally extended plots and remained some of the largest cattle owners in the area, but deficiencies as far as staff were concerned made implementation of the NLHA difficult. For the limited staff that was available to the Native Department, any attempt at curbing madiro ploughing in Sanyati far exceeded their capacity. There were numerous cases of people self-allocating themselves land (a practice known as kuita madiro)82upon arrival from Rhodesdale in 1950, as illustrated by the Gazi case in Madiro Village. Self-allocation and the size of land they took were dependent on the availability of individual or household productive resources like labour, draught power and other equipment [zvibatiso].83When the NLHA was eventually implemented in Sanyati in 1956, it tried to limit allocations to the stipulated eight acres, but people who had self-allocated themselves more than the eight acres tended to resist this limitation. Hence, "illegal extensions [took] place, or the ploughing of vacant plots [was] done by unauthorised people".84 The rampant nature of madiro from 1961 to 1964 and beyond is clearly reflected in what transpired in Madiro Village where chiefly lineages and resident male elders resisted the NLHA because it rendered them powerless in the allocation of land, since their cherished prerogative to distribute or redistribute land among their subjects had been usurped. Land grabbing, compounded by land shortage and the construction of contours for conservation purposes, was therefore common among chiefly and kinship lineages.

Between 1965 and 1966, distinct forms of socio-economic differentiation based on land ownership and peasant production of cotton constantly occurred. UDI had exacerbated racial segregation and clamours for national independence by the majority ofblacks who were deprived of land ownership and water rights. Under UDI, Africans continued to fight for more farm land as a means of accumulation of wealth. Because of cotton's potential to generate cash for the growers and due to its resilience under arid conditions, it became a very popular crop in the Sanyati communal lands, particularly in the 1960s. This stimulated demands for more land as the crop became one of the major bases of peasant differentiation in the pre-irrigation era.85 The differential impact exerted by the cultivation of cotton on the dryland community was enormous as distinct categories of rich and poor farmers were created.86 Cotton commodity production broadened the income and social disparities among dryland communal farmers, and by 1966 the wealth gap between "reserve entrepreneurs" and less-well-to-do farmers had widened even further.

The widening of the wealth gap does not imply, however, that opposition by "reserve entrepreneurs" to the NLHA was any less fierce after having escaped most of its provisions. On the contrary, it implies that resistance from this source was much more important than previously suspected. Hence, alienated and embittered by the attempts of successive settler regimes to wrest control over the dynamics of rural accumulation from their grasp, a significant number of richer peasants turned away from co-operation with government agencies to embracing nationalist politics. Along with rural businessmen, school teachers and headmasters, as well as some chiefs and headmen, they assumed leadership positions in branches of liberation movements, the African National Congress (ANC) and the National Democratic Party (NDP). Undoubtedly, the grievances and aspirations of this "upper 30 per cent of African producers",87 shaped both the kind of opposition to the NLHA and the particular brand of nationalism and rural differentiation which emerged at the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s. The strong opposition registered in Sanyati and other regions was to remain an ingrained feature of differentiation discourse throughout the liberation war years in Zimbabwe.

Conclusion

This article unpacks the events that unfolded and shaped the land and agrarian development of Sanyati in Rhodesia between 1950 and 1966. It argues that the compulsory colonial-era evictions from LONRHO's Rhodesdale Estate, which set the resettlement of people in motion, were triggered by a white-dominated state whose object was clear to those of European origin but less clearly articulated to the African victims of the expulsions from so-called Alienated or Crown Lands to an uninhabitable backwater reserve. The main reason for this land and agrarian policy in colonial Zimbabwe was the deep-seated and long-standing ambition of white Rhodesians to use legislation to re-order African society and development in Sanyati and other parts of the country to create the cherished "white-man's country" without African competition.

The intention to forestall African competition was expressed through pre-and post-1950 legislation such as the LAA and the NLHA which prescribed standards for the separate development of Africans and whites in the country. It was envisaged by the settler state that the NLHA, "modernisation" and the agrarian measures it embraced would promote African livelihoods. However, the "politically-driven" measures were a turning point in colonial Zimbabwe's racialised regime which became highly segregationist in outlook and disadvantaged Africans. While the livelihood outcomes following resettlement in Sanyati were quite impressive, because African farmers were able to live off dryland agriculture as well as generate a surplus for sale from commercial commodity crops like cotton, the farmers challenged and resisted the limits/restrictions imposed by the state on land and livestock ownership which hindered their prospects of wealth-accumulation. State measures were mainly resisted or opposed; the advent of commercial cotton production and its influence on the differentiation process was quite considerable. In fact, colonial legislation which sanctioned the forced removal of African people from Rhodesdale to Sanyati was not designed to promote peasant wealth accumulation, but to re-order African society and development in the area. Any scope for accumulation was strictly limited by government planners who used rigorous bureaucratic procedures to limit the acreage and level of production of individual African producers in line with the quality control and technical criteria set by the state.

The response to this, some communal area farmers in Sanyati took the initiative and were driven to defy the restrictions; in so doing they set themselves as a class apart. Although the state tried to use legislation to arrest rural differentiation, the region witnessed the emergence of affluent categories of rural entrepreneurs. Rural elites survived the impact of the NLHA by employing strategies that ensured that their march towards accumulation would not be obstructed by this law. It can be seen that the impoverished and marginalised position of the peasantry which the state wanted to maintain, did not preclude the emergence of rural differentiation in the area. It was clear that the government intended to use the NLHA to scuttle peasant differentiation and hamper African economic competition, but once the farmers responded by attacking the legislative restrictions a major, unintended, consequence was the emergence of rural differentiation. Differentiation emerged in a way that was never anticipated by the state.

This article demonstrates that the land and agrarian development of the region was not so much conditioned by the polarising intentions of a domineering white-oriented state, but by the reaction of the Africans to a multiplicity of factors, including their forced eviction from "wonderful" Rhodesdale and resettlement in "backwater" Sanyati under the auspices of the 1950/51 Act. African reactions to settling in a frontier agricultural environment can be seen in the indigenous Shangwe and "immigrant" Madheruka's openly radical and clandestine defiance of the restrictions and their subsequent ascendance to privileged positions. The farmers' advance to high social and economic positions in the community was frequently achieved through various royal/chiefly, individual and collective political-manoeuvrings to accumulate land and animals against the authoritarian stipulations of the NLHA. This analysis of forced migration and the reordering of human settlement, agriculture and economic livelihoods, therefore, charts a new course for Zimbabwe's colonial past which hitherto has not received much scholarly attention. It complements earlier studies of African forced movement and resistance to an economically constrictive settler policy in Rhodesia and, hopefully, enhances our understanding of the forces that shaped the land and agricultural dynamics of Sanyati during the pre-irrigation era.

REFERENCES

Acemoglu, D. and Robinson, J.A., Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (Crown Publishing House, NewYork, 2012). [ Links ]

Alexander, J., The Unsettled Land: State-Making and the Politics of Land in Zimbabwe 1893-2003 (James Currey, Oxford, 2006). [ Links ]

Amin, N., "State and Peasantry in Zimbabwe since Independence", European Journal of Development Research, 4,1(1992). [ Links ]

Andersson, Μ. and Green, Ε., "Development under the Surface: Unintended Consequences of Settler Institutions in Southern Rhodesia, 1896-1962", African Economic HistoryWorking Paper Series, 14, 2013. [ Links ]

Anon., The CentralAfrican Daily News, 3 January 1962. [ Links ]

Bhebe, N., B. Burombo: African Politics in Zimbabwe, 1947-1958 (College Press, Harare, 1989). [ Links ]

Bratton, Μ., From Rhodesia to Zimbabwe. Beyond Community Development: The Political Economy of Rural Administration in Zimbabwe (Catholic Institute for International Relations, London, 1978). [ Links ]

Bulman, Μ., The Native Land Husbandry Act of Southern Rhodesia: A Failure in Land Reform (Tribal Areas ofRhodesia Research Foundation, Salisbury, 1975). [ Links ]

Cheater, A.P., "Idioms of Accumulation: Socio-Economic Development in an African Freehold Farming Area in Rhodesia", PhD thesis, University of Natal, 1975. [ Links ]

Cousins, B., Weiner, D. and Amin, N., "Social Differentiation in the Communal Lands", Review ofAfrican Political Economy, 53(1992). [ Links ]

Cowen, M.P., "Capital, Class and Peasant Households", Unpublished Paper, Nairobi, 1976. [ Links ]

Duggan, W., "The Native Land Husbandry Act of 1951 and the Rural African Middle Class of Southern Rhodesia", African Afairs, 79(1980). [ Links ]

Floyd, B., "Changing Patterns of African Land Use in Southern Rhodesia", PhD thesis, Syracuse University, 1959. [ Links ]

Gjerstad, 0. (ed.), The Organizer: Story ofTemba Moyo (LSM Press, Richmond, British Columbia, Canada, 1974). [ Links ]

Godlonton Commission, Report of Native Production and Trade Commission (Government Printers, Salisbury, 1944). [ Links ]

Government of Southern Rhodesia, What the Native Land Husbandry Act Means to the Rural African and to Southern Rhodesia: A Five Year Plan that will Revolutionise African Agriculture (Government Printers, Salisbury, 1955). [ Links ]

Government of Southern Rhodesia, Second Report of the Select Committee on Resettlement of Natives (Government Printers, Salisbury, 1961) [ Links ]

Holleman, J.F., Chief, Council and Commissioner: Some Problems of Government in Rhodesia (Oxford University Press, London, 1969). [ Links ]

Kay, G., Rhodesia: A Human Geography (University of London Press, London, 1970). [ Links ]

Le Roux, A.A., "A Survey of Proposals for the Development of African Agriculture in Rhodesia", Proceedings ofthe GeographicalAssociation of Rhodesia, 3 (1970). [ Links ]

Machingaidze, V.E.M., "Agrarian Change from Above: The Southern Rhodesian Native Land Husbandry Act and African Response", International Journal of African HistoricalStudies, 24, 3(1991). [ Links ]

Madzorera, A., Interview conducted by Staunton, I., cited in Mother of Revolution: The WarExperiences of Thirty Zimbabwean Women (James Currey, London, 1990). [ Links ]

Masst, M., "The Harvest of Independence: Commodity Boom and Socio-Economic Differentiation among Peasants in Zimbabwe", PhD thesis, Roskilde University, 1996. [ Links ]

Masters, W.A., Government and Agriculture in Zimbabwe (Praeger Publishers, London, 1994). [ Links ]

Mlambo, A.S., "Building a White Man's Country: Aspects of White Immigration into Rhodesia up to World War II", Zambezia, 25, 2(1998). [ Links ]

Moyo, S., The Land Question in Zimbabwe (Sapes, Harare, 1995). [ Links ]

Nyambara, P.S., "A History of Land Acquisition in Gokwe, Northwestern Zimbabwe, 1945-1997", PhD thesis, Northwestern University, June 1999. [ Links ]

Nyambara, P.S., "That Place was Wonderful! African Tenants in Rhodesdale Estate, Colonial Zimbabwe, c. 1900-1952", The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 38, 2(2005). [ Links ]

Nyandoro, M., "Development and Differentiation in the Post-Independence Era: Continuity or Change in ARDA-Sanyati Irrigation in Zimbabwe (1980-1990)", Journal of African Historical Review, 41, 1(July 2009). [ Links ]

Nyandoro, M., "Development and Differentiation: The Case of TILCOR/ARDA Irrigation Activities in Sanyati (Zimbabwe), 1939 to 2000", PhD thesis, University of Pretoria, 2007. [ Links ]

Nyandoro, M., "Zimbabwe's Land Struggles and Land Rights in Historical Perspective: The Case of Gowe-Sanyati Irrigation (1950-2000)", Historia, 57, 2(2012). [ Links ]

Palmer, R.H., Land and Racial Domination in Rhodesia (Heinemann, London, 1977). [ Links ]

Phimister, I., "Rethinking the Reserves: Southern Rhodesia's Land Husbandry Act Reviewed",Journal of Southern African Studies, 19, 2(1993). [ Links ]

Phimister, I., An Economic and Social History of Zimbabwe, 1890-1948: Capital Accumulation and Class Struggle (Longman, London, 1988). [ Links ]

Ranger, T.O., "The Communal Areas of Zimbabwe", in T. Bassett and D. Crummey (eds), Land in African Agrarian Systems (University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1993). [ Links ]

Ranger, T.O., Peasant Consciousness and Guerrilla War in Zimbabwe: A Comparative Study (Zimbabwe Publishing House, Harare, 1985). [ Links ]

Roberts, A.,A History of Zambia (Heinemann, London, 1976). [ Links ]

Shutt, A.K., "Purchase Area Farmers and the Middle Class of Southern Rhodesia, c. 1931-1952", The InternationalJournal ofAfrican Historical Studies, 30, 3(1997). [ Links ]

Worby, E., "'Discipline without Oppression': Sequence, Timing and Marginality in Southern Rhodesia's Post-War Development Regime", The Journal of African History,41,1(2000). [ Links ]

Worby, E., "A Re-divided Land? New Agrarian Conflicts and Questions in Zimbabwe", Journal of Agrarian Change, 1, 4(October 2001). [ Links ]

Worby, E., "Inscribing the State at the 'Edge of Beyond': Danger and Development in North-Western Zimbabwe", Political and LegalAnthropology Review, 21(1998). [ Links ]

Worby, E., "Remaking Labour, Reshaping Identity: Cotton, Commoditisation and the Culture of Modernity in North Western Zimbabwe", PhD, McGill University, 1992. [ Links ]

Worby, E., "What Does Agrarian Wage-Labour Signify? Cotton, Commoditisation and Social Form in Gokwe, Zimbabwe",Journal ofPeasantStudies, 23,1(1995). [ Links ]

Yudelman, M., Africans on the Land: Problems of African Agricultural Development in Southern, Central and East Africa, with Special Reference to Southern Rhodesia (Harvard University Press, Cambridge: MA, 1964). [ Links ]

* He has diverse interests in water, energy, land, irrigation agriculture, poverty, sustainability and economic development, migration, climate change and environmentresearch.

1 N. Bhebe, B. Burombo: African Politicsin Zimbabwe, 1947-1958 (College Press, Harare, 1989),p74.

2 W.A. Masters, Government and Agriculture in Zimbabwe (Praeger, London, 1994), p 3; A.S. Mlambo, "Building a White Man's Country: Aspects of White Immigration into Rhodesia up to World War II", Zambezia, 25, 2(1998), pp 123-146; M. Nyandoro, "Development and Differentiation: The Case of TILCOR/ARDA Irrigation Activities in Sanyati (Zimbabwe), 1939 to 2000", PhD thesis, University of Pretoria, 2007, p46.

3 The categories into which the country was divided have been illustrated by G. Kay, Rhodesia: A Human Geography (University of London Press, London, 1970), p 51. See also Government of Southern Rhodesia, Second Report of the Select Committee on ResettlementofNatives (Government Printers, Salisbury, 1961), p 15.

4 National Archives of Zimbabwe (hereafter NAZ), S1194/190/1, Land for Native Occupation, Reports of the ad-hoc Committee, 1946/47.

5 J.F. Holleman, Chief, Council and Commissioner: Some Problems of Government in Rhodesia (Oxford University Press, London, 1969), p 61.

6 Godlonton Commission, Report of Native Production and Trade Commission (Government Printers, Salisbury, 1944).

7 Godlonton Commission. For background to and implementation of the NLHA, see the government policy document, Government of Southern Rhodesia, What the Native Land Husbandry Act Means to the Rural African and to Southern Rhodesia: A Five Year Plan that will Revolutionise African Agriculture (Government Printers, Salisbury, 1955). Several writings have given different interpretations of the NLHA, e.g. B. Floyd, "Changing Patterns of African Land Use in Southern Rhodesia", PhD thesis, Syracuse University, 1959; M. Yudelman, Africans on the Land: Problems of African Agricultural Development in Southern, Central and East Africa, with Special Reference to Southern Rhodesia (Harvard University Press, Cambridge: MA, 1964); W. Duggan, "The Native Land Husbandry Act of 1951 and the Rural African Middle Class of Southern Rhodesia", African Affairs, 79(1980), p 315; M. Bulman, The Native Land Husbandry Act of Southern Rhodesia: A Failure in Land Reform (Tribal Areas of Rhodesia Research Foundation, Salisbury, 1975); and V.E.M. Machingaidze, "Agrarian Change from Above: The Southern Rhodesian Native Land Husbandry Act and African Response", InternationalJournalofAfrican HistoricalStudies, 24, 3(1991), pp 557-589.

8 Godlonton Commission Report, p 9.

9 Godlonton Commission Report, p 9.

10 Holleman, Chief, Council, and Commissioner, p 46.

11 P.S. Nyambara, "That Place was Wonderful! African Tenants in Rhodesdale Estate, Colonial Zimbabwe, c. 1900-1952", The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 38, 2(2005), pp 267-299.

12 Nyambara, "That Place was Wonderful!", pp 267-299.

13 Bhebe, B. Burombo; E. Worby, "Remaking Labour, Reshaping Identity: Cotton, Commoditisation and the Culture of Modernity in North Western Zimbabwe", PhD thesis, McGill University, 1992; Chief M.T. Wozhele, personal interview conducted by the author, Chiefs Court, "Old Council"/Wozhele Business Centre, Sanyati, 17 October 2004. During the interview, the chief was ably assisted by Headman Samson Mudzingwa and Maunganidze Nyahwa (all were members of the chiefs court).

14 T.O. Ranger, "The Communal Areas of Zimbabwe", in T. Bassett and D. Crummey (eds), Land in African Agrarian Systems (University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1993), pp 354-388; T.O. Ranger, Peasant Consciousness and Guerrilla War in Zimbabwe: A ComparativeStudy (Zimbabwe Publishing House, Harare, 1985).

15 On white immigration to Rhodesia up to WWII, see Mlambo, "Building a White Man's Country".

16 Holleman, Chief, Council and Commissioner.

17 E. Worby, "What Does Agrarian Wage-Labour Signify? Cotton, Commoditisation and Social Form in Gokwe, Zimbabwe",/ournal of Peasant Studies, 23,1(1995), pp 1-29; P. S. Nyambara, "A History of Land Acquisition in Gokwe, Northwestern Zimbabwe, 1945-1997", PhD thesis, Northwestern University, June 1999.

18 Among indigenes a distinction is made between autochthons (varidzi venyika, literally, "owners of the land") and stranger-conquerors (vatorwa, literally, "those who have taken"). The latter arrived in Sanyati under the leadership of Chief Wozhele from Rhodesdale in 1950. See Worby, "Remaking Labour", p 6; M. Nyandoro, "Development and Differentiation in the Post-Independence Era: Continuity or Change in ARDA-Sanyati Irrigation in Zimbabwe (1980-1990]", Journal of African HistoricalReview, 41,1 (July 2009], pp 51-89.