Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Historia

On-line version ISSN 2309-8392

Print version ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.62 n.1 Durban May. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8392/2017/v62n1a2

ARTICLES

A clash of military doctrine: Brigadier-General Wilfrid Malleson and the South Africans at Salaita Hill, February 1916

David Brock Katz*

PhD (Mil) candidate in the Department of Military Science, Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

Brigadier-General Wilfrid Malleson (1866-1946) received his commission into the Royal Artillery in 1886 and transferred to the Indian Army in 1904. He was relatively inexperienced in combat having served on the staff of Field Marshal Kitchener as part of the British military mission in Afghanistan. Malleson was later transferred to East Africa where the 2nd South African Division fell under his overall command during the catastrophic attack on Salaita Hill. This was the first occasion, since the formation of the Union Defence Force (UDF) in 1912, where a British officer commanded South African troops in battle - with disastrous consequences. There were deep underlying reasons behind the fledgling UDF's first defeat at the hands of the veteran Germans, commanded by the wily Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (1870-1964). Malleson's lack of combat experience was a factor in the defeat, but more importantly, the uninspired plan of attack doomed the UDF to failure.

Keywords: Jan Smuts; South Africa; Von Lettow-Vorbeck; German East Africa; military doctrine; Union Defence Force; Salaita Hill; manoeuvre warfare.

OPSOMMING

Brigadier-Generaal Wilfrid Malleson (1966-1946) het in 1886 sy kommissie ontvang in die Koninklike Artillerie, waarna hy in 1904 na die Indiese Leër toe verplaas is. Ten spyte daarvan dat hy deel was van veldmaarskalk Kitchener se staf tydens die Britse militêre missie in Afghanistan, was sy gevegservaring relatief beperk. Malleson is later verplaas na Oos-Afrika waar hy in bevel was van die Suid-Afrikaanse 2de Divisie tydens die katastrofiese aanval op Salaita-heuwel. Dit was die eerste geval, sedert die stigting van die Unieverdedigingsmag (UVM) in 1912, dat ʼn Britse offisier in bevel was van Suid-Afrikaanse troepe tydens ʼn geveg - met rampspoedige gevolge. Daar was diep onderliggende redes vir die UVM se eerste nederlaag teen ervare Duitse troepe onder die bevel van die uitgeslape kolonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (1870-1964). Hoewel Malleson se gebrek aan gevegservaring ʼn rol gespeel het in die nederlaag, was dit grotendeels die ongeïnspireerde plan vir die aanval wat gelei het tot die UVM se mislukking.

Sleutelwoorde: Jan Smuts; Suid-Afrika; Von Lettow-Vorbeck; Duits Oos-Afrika; militêre doctrine; Unieverdedigingsmag; Salaita-heuwel; maneuvreerende oorlogsvoering.

Background

The Union Defence Force (UDF) was unlike that of the other belligerents fighting it out in the world's first global conflict. South Africa's otherness came about from the fact that the UDF was comprised of former enemies. A mere 12 years before the First World War, Englishman and Boer were bitter foes, locked in mortal combat. The UDF's establishment in 1912 was two years after the declaration of the Union of South Africa in 1910. It was a miraculous exercise in conciliation. The formation of the Union of South Africa was an effort to consolidate and merge the disparate aims of the various nationalities living within its borders with those of the British Empire.1 The hope was that Afrikaner nationalists, seeking varying degrees of self-determination, would combine with English-speakers, those who owed their allegiance to the British Empire, to form a political entity out of a mere geographical expression.

An overriding political motive gave impetus to the formation of the UDF in 1912. It was an exercise in nation building more than the creation of a force designed to secure its borders from enemy invaders. Political compromise underpinned its structures and the authorities made appointments with more of an eye to soothing historical animosities than on skill and expertise. The UDF's military doctrine incorporated that of the Boer forces, the former colonial armies and the British Army. The military perceived the immediate threat as internal strife emanating from disaffected and disenfranchised blacks. The military planners composed the thought, doctrine and structure of the fledgling UDF around the unlikelihood of a foreign invasion by a European power.2

Indeed, the UDF's first actions in the short two years between its formation and the advent of the First World War were against its citizenry. Authorities made use of imperial troops to contain a general strike in July 1913. Jan Christiaan Smuts (1870-1950), minister of Interior, Defence and Mines, was loathe to use imperial troops and deployed the UDF to crush a more serious strike in January 1914.3 The UDF's first noteworthy military test occurred shortly after South Africa entered the First World War and it was once again against her citizens. The campaign against their next-door neighbours in German South West Africa (GSWA) would have to wait. The UDF occupied itself in quashing 11 000 Afrikaner rebels, led by former members of the UDF, between August and December 1914. The fact that the UDF was able to complete this major internecine operation successfully was proof of the measures which Smuts and Louis Botha (1862-1919), the prime minister, introduced to the fledgling and politically sensitive UDF.4

After the UDF successfully suppressed the rebellion, it was time to deal with the Germans ensconced across the border in GSWA. That the South African forces numbered approximately 50 000 compared to the modest German force numbering about 7 000, did not tempt them to conduct a costly war of annihilation. They avoided pitched battles in favour of advancing on multiple fronts. By using the threat of envelopment, the UDF dislodged the Germans from their prepared positions and made them defend locations not of their primary choice. The South Africans forced the Germans to surrender on 9 July 1915 with their fighting capability almost intact. The successful conclusion of the campaign, at relatively low human cost, was vindication of manoeuvre warfare and carried all the hallmarks of a South African "way of war".5

The battle for Salaita Hill took place at the beginning of 1916. It was the first occasion that South African troops, under British command, engaged with the Germans in German East Africa (GEA). Here conditions and the enemy were unlike anything that the South Africans encountered before. When one assesses the battle of Salaita Hill, one has to keep in mind the very real political sensitivities behind every battle decision. No army in the world is devoid of political sensitivity, in fact, one could say that they are the product of the political collective. The UDF was a reflection of the society that formed it. However, the fact that South Africa was not a homogenous society and that its army consisted of former adversaries thrown together, influenced its performance on the battlefield in a unique way.

South Africa also suffered from an inferiority complex; she sought status within the Empire and the successful waging of warfare would not only bring prestige but also provide nation building. South Africa harboured sub-imperialistic ambitions leading to deep-seated expansionist desires in Africa. Therefore, in conducting a war in Africa, on behalf of the British Empire, South Africa sought to acquire certain territorial assets at a minimum cost in human lives thus gaining prestige within the Empire and forging a national identity for its divided nation.6 All these influences formed a complex political web, which shaped South African military doctrine.

Salaita Hill was South Africa's first battle in GEA and reveals the UDF's cohesion, doctrine, training, political outlook, weaknesses, and strengths built during its peacetime training process. Salaita Hill was a test of all the UDF's preparations and doctrines. Only once an army has engaged in a number of battles and conducted warfare for a lengthy period, do other factors come into play, which forge the efficacy of its fighting power beyond its initial training.7 This article revisits the battle of Salaita Hill, making use of primary and secondary sources to trace the doctrinal development of the UDF and explore the differences between the British and South African way of war. Malleson and Salaita are the lens through which the clash of military doctrine is revealed.

The clash of battlefield doctrine

Military doctrine is a set of fundamental military principles designed to gain advantage and eventually overcome an enemy. It is a formal expression of military knowledge and thought to guide military forces on how they should conduct their operational art and tactics to achieve their strategic objectives. It is descriptive rather than prescriptive, outlining how the army thinks about fighting, but not how to fight. It is a guide to military activity and does not replace initiative and judgement on the battlefield.8 The doctrinal lens needs continual adjustment to stay in focus with the introduction of improved and new technologies into warfare, thereby throwing the relationship between the different arms (artillery, air, armour, and infantry) out of synchrony.9

At the outbreak of the First World War, the British system of warfare had not advanced much from the Anglo-Boer War and this was particularly true in Africa. At the outset of the Anglo-Boer War, the British made use of what Thomas Pakenham labels, "the Aldershot set-piece in three acts". This one-day action comprised the first act - an artillery duel, and a preparation of the ground. The second act consisted of the infantry launching a frontal assault in open order formation, and then ultimately charging the enemy position with fixed bayonets once they were close enough. The final act was a cavalry charge to cut off the enemy's retreat.10 This anachronistic form of warfare cost the British dearly in the Anglo-Boer War. The set piece action was, of course, devoid of operational art and lacked combined arms warfare with minimal cooperation between the three different arms (infantry-artillery- cavalry).

However, British military doctrine did not completely stand still and evolved to a certain extent because of the lessons learnt in the Boer War. Costly battlefield experiences resulted in the publication of the Infantry Training Manual of 1902.11 The manual supported offensive action over defensive action but categorically rejected simple brute force and the use of frontal attacks across open, fire-swept ground.12 The manual correctly suggested that turning movements would yield better results for far fewer casualties on a modern battlefield where defensive firepower could overwhelm even large numerical advantages. It identified the need for combined arms warfare and close cooperation between arms but offered minimal suggestions on a systematic method of implementation.13 The Russo-Japanese War 1905 served as a catalyst in revitalising the frontal assault for influential British military thinkers who emphasised willpower over firepower. The Field Service Regulations 190914 published after the Infantry Training Manual 1902, began to reflect these subtle changes. It de-emphasised flank attacks and gave preference to the "final assault" over developing superior firepower. The belief that courage alone could overcome defensive firepower began to take hold. The newfound preference for bold offensive action steadily eroded the cautious approach that emerged directly after the Boer War. The result was a downgrade in the belief of firepower and movement, replacing it with faith in moral supremacy and willpower.15 Military theorists saw the Boer War as an aberration from the conditions of a European war in which the lessons learnt were not totally transferable or applicable to European conditions.16

The Germans, on the other hand, were much more flexible in their approach to warfare. German military culture prized initiative down to the lowest levels of command. Their mission-type tactics (Auftragstaktik) was a central component of the German Armed Forces since the nineteenth century. This military culture allowed subordinates to make decisions on the spot down to the lowest levels of command, on condition that they complied with the overall commander's objective.17 The German army encouraged aggressive tactics and their default was to attack or counter-attack from nearly every situation, even in the face of a numerical disadvantage, or even when circumstances seemed unfavourable. The Germans were also proponents of combined arms warfare and their frequent military exercises stressed cooperation between the different arms of service. They practised manoeuvre warfare (Bewegungskrieg) where they favoured mobility over remaining static (Stellungskrieg). The Germans sought to manoeuvre their forces to place them in the most advantageous position where they could overwhelm an unsuspecting enemy. Often Germans would attempt to encircle their opponent and after that, try to destroy them in a cauldron battle (Kesselshlacht). Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck was a product of this German military training and his conduct of the GEA campaign, as commander of the German forces, conformed to the prescribed German doctrine of the time.18

The UDF's military doctrine was a derivation of a combination of the forces which took part in the Anglo-Boer War. The Boers and subsequently the UDF, were certainly averse to conducting expensive and often futile frontal attacks. The Boers manoeuvred to fight while the British, tied into their large logistic needs, fought in order to manoeuvre. Richard Meinertzhagen (1878-1967), an observer, participant, and a bitter critic of the conduct of the war in GEA, gives some insight into the British penchant for frontal assault and he explained it thus:

Manoeuvre is a peculiar form of war which I do not understand and which I doubt will succeed except at great expense in men and money. … A series of manoeuvres will only drag operations on for years. Smuts should bring him [Lettow-Vorbeck] to battle and instead of manoeuvring him out of position, should endeavour to surround and annihilate him, no matter what are our casualties.19

The Boer forces were highly mobile, being essentially formed from mounted infantry. They preferred to manoeuvre by conducting a strategic offensive and a tactical defensive. Through manoeuvre and high mobility, they often forced the British to attack in circumstances unfavourable to the attacker. Therefore, the Boers used their superior mobility to ensure that they would conduct a battle on ground of their choosing. Their superior mobility also allowed them to retreat out of harm's way should conditions on the battlefield warrant a withdrawal. The Boer style of command allowed for a greater amount of initiative on the battlefield compared to their British opponents.20 However, this freedom to exercise initiative was often unbridled and practised out of the confines of an overall objective as prescribed in German doctrine. The lack of a formal conventional command structure in the Boer forces often led to unexpected results on the battlefield. The South African mounted forces supplied to GEA were distinctly Afrikaner in origin, while the foot infantry tended to be predominantly of English extraction.21 As a result, the UDF was an interesting combination of opposing doctrines and former enemies.22 Smuts and the UDF adopted this way of war and put it into practice with good effect in GSWA and with mixed results in GEA. The UDF, under British command, was unable to exercise its manoeuvre doctrine at Salaita Hill as practised successfully in GSWA in 1915 under Botha and the Kilimanjaro operations in GEA in 1916 under Smuts.

The lead-up to the battle of Salaita Hill

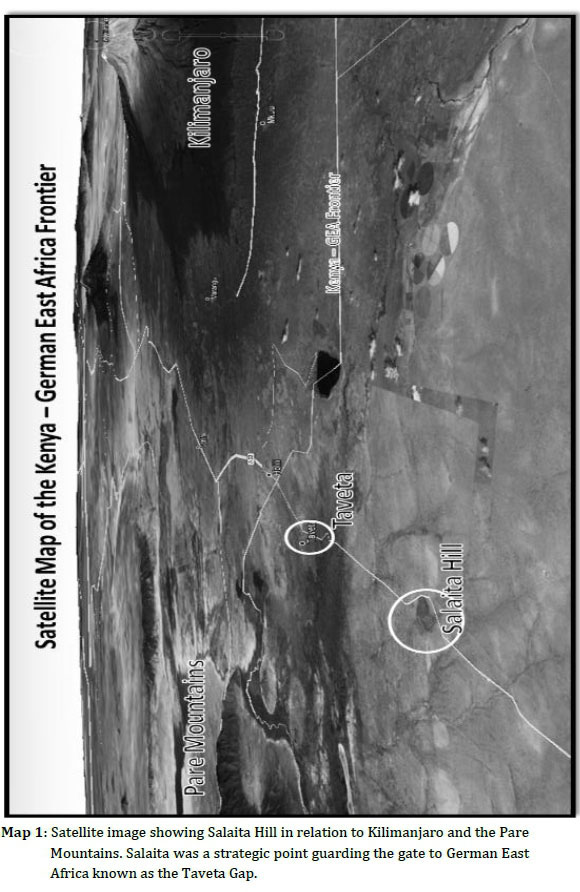

Salaita Hill was a strategic outpost constructed on British East African soil and held by the Germans as part of a defensive system deployed in depth. Salaita was the first in a series of defensive positions occupied by the Germans, which guarded the Taveta Gap, the gateway to Kenya/GEA (see Map 1). Its forward position also facilitated the raiding of the British logistical infrastructure. Raiding was an activity the Germans engaged in often with great success and to the extreme irritation of the British.23 Salaita Hill afforded the Germans a useful observation post providing the only high ground astride the single road leading to Taveta, on an otherwise flat almost featureless plateau. The impenetrable Pare Mountains in the south and the dominating Kilimanjaro to the north flanked the 25 kilometre Taveta Gap.

The British fared poorly in the GEA campaign thus far and there was concern that this was, "damaging to our prestige among the native races".24 Most importantly, Salaita was one of the only pieces of British territory that the Germans occupied in the First World War.25 The political value of removing them from this piece of British real estate placed immense pressure on the military to do so as soon as it was possible. The arrival of strong South African forces in Kenya in February 1916, presented the British with an opportunity to remove the Germans before the arrival of Smuts. The British conducted the Salaita operation in terms of a strategy to be undertaken before the onset of the rains in April termed, "preliminary operations." These operations would consist of capturing strong German outposts in British East Africa to restore prestige and provide sound jumping off points when the rains ceased in June.26

Malleson found himself in command of the British 2nd Division, which was earmarked to launch the attack on Salaita Hill. He was relatively inexperienced having seen very little in the way of combat and even less time in command (see Figure 1). Meinertzhagen describes Malleson as having no knowledge of command and,

… a bad man, clever as a monkey, but hopelessly unreliable and with a nasty record behind him. He is by far the cleverest man out here, but having spent all his service in an Ordinance Office, knows very little about active operations and still less of the usual courtesies amongst British officers. He comes from a class which would wreck the Empire to advance himself. … [He] is loathed and despised as an overbearing bully, ill mannered, and a rotten soldier.27

Meinertzhagen was not alone in rating Malleson's generalship as below par and Smuts was less than complimentary when he canvassed for his removal on the 15 March 1916 after Malleson asked to be relieved of his command "owing to serious indisposition":

I regret to say that after the Salaita fiasco on the 12 February there is very little confidence in the fighting ability of Malleson and a change in the command of the 1st East African Brigade is also desirable; Tighe considers him a capable administrator and I hope his talents could be better employed by the War Office in an administrative capacity.28

The South African exploratory mission to GEA at the end of 1915 found Major-General Tighe to be of "nervous manner, lacking in strength of character and forcefulness, lacks experience of conducting operations of a large scale, cannot look at things from a big point of view [and] does not realise the use to which mounted troops can be put …" Hughes and Van Deventer were even less complimentary about Brigadier-General Malleson. "Neither of us were impressed by this officer… he was not a big man in the sense of being strong and resourceful."29

On 1 May 1915, Malleson assumed command of the Voi area, which extended from the coast to Kilimanjaro. On 13 July 1915, he advanced on Mbuyuni with 1 100 men, eight machine guns, and three pieces of artillery. He launched an attack on the morning of 14 July against the entrenched German positions, after a night march to bring them into position. It took the form of a frontal assault supplemented with a weak flanking attack on the enemy left.30 The entire operation harked back to the tactics employed by the British in the opening stages of the Anglo-Boer War - with disastrous results. In this unsuccessful action, he suffered casualties of 170 men and one machine gun. He delivered a frontal attack on a carefully prepared position against a numerically superior enemy with no hope of success.31 Capell sums up the result of the fiasco as "… strengthening of the already fine morale of the enemy".32 It was an inauspicious beginning to an unremarkable combat career.

With little success or experience behind his name, Malleson drew up operational orders on 11 February 1916 for an attack on the German positions at Salaita Hill. His motivation for the attack before the arrival of Smuts, according to Malleson, was an order he received on 10 February 1916, that he was to capture the hill before 14 February. These orders apparently originated from General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien (1858-1930) in South Africa, travelling en route to assume the command in East Africa.33

Smith-Dorrien received his appointment as the general officer in command of East Africa on 22 November 1915. Unfortunately, he contracted pneumonia on his voyage to South Africa and was unable to take up his command. The orders first took the form of a query issued by Smith-Dorrien on 4 February 1916 to Major-General M. Tighe, commander of the British forces in East Africa, asking when he would attack Salaita Hill. Tighe replied on the 7 February that he would attack Salaita between 12 and 14 February.34 There is little evidence to suggest that Smith-Dorrien or anyone else informed Smuts of this planned attack on Salaita Hill when the latter replaced him on short notice.It is unlikely that Smuts would have condoned a frontal attack of this nature.

The British appointed Smuts as Smith-Dorrien's successor on 6 February 1916 and he arrived in East Africa on 19 February.35 It seems strange that the British would launch a major attack before the arrival of Smuts on a query issued by Smith-Dorrien on 4 February 1916. Logic dictates that the new commander would have wanted to be present at the scene, instead of languishing on a ship sailing for East Africa. The suggestion for the attack emanated from Smith-Dorrien who was no longer in command and the attack took place a day after Smuts departed for East Africa.36 It seems that Malleson and Tighe were anxious for a victory before Smuts's arrival.

This was not the first time that the British attempted to assail Salaita. The previous effort took place on 29 March 1915 and took the form of a probing attack by two companies, two machine guns and a single artillery piece.37 Meinertzhagen described the assault as "aimless, objectless and dangerous". Major G. Newcome, true to prevailing British doctrine, executed an unimaginative frontal assault on the hill. A German counter-attack on the right flank readily reinforced by the main German base at Taveta a mere 10 kilometres away, drove him back. The British attack failed miserably with five killed and two machine guns abandoned in the panic of retreat.38 The way the Germans were able to reinforce Salaita rapidly and launch a flank attack was a precursor to what Malleson could expect when he attacked. According to Malleson's post-battle report, he expected the South Africans to encounter the German "hostile reserves" that he believed resided on the west side of Salaita Hill. Therefore, any flank attack could have reasonably anticipated stiff resistance at any time in their manoeuvre.39

Malleson resolved to launch his attack with a bit more imagination and flair than that of Newcome. He was determined to remove the enemy on Salaita via a turning movement, which would envelop the German positions on the hill from the north (see Malleson's Map 3). The Divisional War Diary makes it clear that the intention of the attack was to remove the enemy and secure Salaita Hill.40 The newly arrived, fresh (inexperienced) South Africans would conduct this flanking manoeuvre. The Germans would be pinned on their front by the veteran 1st East African Infantry Brigade, a formation which had seen most of the action in the campaign thus far. Thus, Malleson chose to leave it to the "green", recently arrived41 South Africans, to execute a flanking manoeuvre against an enemy who had rebuffed similar assaults on two previous occasions at Salaita on 29 March 1915 and Mbuyuni on 14 July 1915.42 Malleson comments on the South African's inexperience in a note he penned on the 20 April 1917:

So far as I am aware the South Africans were the only overseas contingent put straight into the field. All other contingents had months of thorough training in England or Egypt before being sent into the field. Br[igadier] General Berenge [sic, Berrange], Commanding 3rd S.A. Brigade, told me that the greater portion of his men had been given their arms and uniform on board the transport at Durban.43

The South African troops were woefully undertrained; the time between recruitment and seeing their first action, amounted to only a matter of weeks.45 Although many of the officers were veterans of the Anglo-Boer War there was a shortage of experienced NCOs. Most of the men were hastily recruited, undertrained teenagers and there was little time to hone them into an effective fighting force.46

Malleson's plan of attack on Salaita Hill

Malleson's decision to split his holding forces (1st East African Brigade) and his offensive brigade (2nd South African Infantry Brigade) equally, worked against the basic principle in warfare of concentration and economy of force.47 The South African outflanking manoeuvre was clearly the point of maximum effort and as such should have attracted the bulk of the troops available. As it was, there was no discernible reserve placed under Brigadier-General P.S. Beves's (1863-1924) command to reinforce success, or if necessary, to ward off an enemy counterattack (see Table 2). It was counter-intuitive to the principle of unity of command, whereby unity of effort develops by appointing a responsible commander and placing the necessary resources at his disposal to reach the objective. The flank attack could have achieved an overwhelming superiority had Malleson thinned out the static forces holding the western front of Salaita and creating a reserve for the flanking attack.

The brunt of the turning movement was conducted by the 2nd South African Infantry Brigade under Beves, a veteran brigade commander under Brigadier-General Sir Duncan McKenzie in the GSWA campaign. Beves served as a captain in the Anglo-Boer War in a regular British infantry regiment and saw extensive action at Lombard's Kop and the defence of Ladysmith. He went on to command a battalion from 4 September 1900 to 15 May 1901. After the war he commanded the Transvaal Volunteers until 1912 and then became commandant of cadets in the UDF.48 Collyer describes him as, "an officer of Regimental experience, careful, and attentive to the comforts and needs of those whom he commanded".49 Malleson is at pains to explain that he did not design the action, especially the flanking movement, to manoeuvre the Germans out of Salaita. To do so would have risked the intervention of the 6 000 German troops in the Taveta vicinity and he did not have the luxury of the extra 10 000 soldiers that Smuts fielded a month later. He was fearful of "splitting up" an already inferior force that a deeper flanking attack would require.50

Common sense would dictate that Malleson should have assigned the more difficult role of enveloping Salaita to the more experienced 1st East African Infantry Brigade rather than the relatively inexperienced 2nd South African Infantry Brigade. They had barely arrived in GEA and had little time to acclimatise or train in their new surroundings.51 Malleson himself comments that the South Africans were the only contingent put straight into battle. "All other contingents had months of thorough training in England or Egypt before being sent to the field."52 It would have been more prudent to allow the South Africans to assume the static role in front of Salaita, which would have afforded them a valuable learning experience against a veteran enemy who was the wily victor of many battles. However, Malleson in his wisdom seems to have felt that his veteran troops deserved a break after being continuously on campaign for many months.

The depth of Malleson's proposed outflanking manoeuvre can also be called into question. The further north and thus the wider the manoeuvre described by the outflanking units, the more the German positions at Salaita would be unhinged. A manoeuvre designed to arrive in the rear of Salaita would have disrupted the supply lines to those defending the hill, forcing the Germans to either abandon their positions or launch a counter-attack on a numerically superior enemy on ground of the enemy's choosing. The main weakness of Salaita was that it did not have a supply of water. The defenders of Salaita carried in every drop of water from the west and this supply line was extremely vulnerable to disruption, which would have made the defence of Salaita untenable.53 As it was, Malleson's flanking attack was a very shallow affair, barely stretching 2 kilometres to the Germans left flank on the hill. The lack of depth of the attack allowed the Germans the opportunity to extend their flank and meet their attackers from prepared positions close to Salaita. If one compares Malleson's hand-drawn map (Map 2) to the map in Collyer's official history (Map 3), it is immediately apparent that the South African flanking manoeuvre was even shallower than Malleson had intended. The South African outflanking manoeuvre had unintentionally developed into a frontal assault and they delivered it well to the northeast instead of to the northwest.

Malleson does offer his reasons for resorting to a tactical solution rather than launching a flanking manoeuvre at the operational level. He explains his motivation for adopting a shallow outflanking manoeuvre as follows:

The information supplied by G.H.Q was to the effect that the enemy had in and around Taveta, which is in close supporting distance of Salaita, not less than 6 000 men. As I could not bring more than 4 500 rifles to the actual attack there could be no question of trying to manoeuvre the enemy out of Salaita, as was possible a month later with 10 000 additional troops, as to make any attempt would have involved splitting up an already inferior force, and thus risk defeat in detail.54

Therefore, using dubious numbers as an excuse not to launch a more imaginative attack, Malleson resorted to what turned out to be a costly unimaginative frontal assault on a well-prepared position without the element of surprise.

At the outset, the British underestimated the enemy forces facing them, despite the ground and air reconnaissance undertaken in the few days before the operation.55 They estimated the German strength to be in the region of 300 men entrenched with machine guns but with no artillery.56 However, this flies in the face of a report produced by Malleson, shortly after the battle, where he speaks of intelligence reporting the availability of 2 000 Germans near Salaita.57 One can compare this with the actual figures shown in Table 1. Malleson, despite the woeful underestimation of the forces in front of him (according to the British official history), did enjoy a substantial numerical superiority in men, machine guns, and artillery. According to Malleson's account directly after the battle and then again 14 months later, he expected there to be considerable German resistance when he attacked Salaita. The result of the battle would depend on the skilful use, or otherwise, of his numerical advantage in directing his forces to the centre of gravity of his attack (Schwerpunkt).

Besides getting the numbers wrong, Malleson grossly underestimated the fighting power of the enemy and its ability to move reinforcements situated some 7 kilometres away from the battlefield quickly into battle. The British plan depended on a preconceived notion that they could capture Salaita Hill before the enemy was able to send reinforcements. They also underrated the strength of the enemy defences after two previous unsuccessful attacks on the same positions. The Germans occupied the same ground for many months and made full use of the many opportunities to build formidable all-around defences and reconnoitre the area thoroughly.60 Then too, the South Africans were guilty of making light of the resourcefulness and skill of the enemy, dismissing them as mostly native troops. Their contempt for the enemy matched their low regard for the Indian soldiers who ironically come to their rescue in the aftermath of the fiasco of Salaita.61

Beves received his divisional order on 11/12 February, the night before the operation; it stated that his brigade would attack the enemy positions to the northeast of Salaita Hill. Beves prudently sought further information as to the proposed action that would take place subsequent to the occupation of the enemy positions. Malleson informed Beves that no discussion would be entertained on the actual orders.62 Beves took the opportunity to raise several concerns on the execution of the operation. He was apprehensive about the lack of surprise because his brigade would be in full view from Salaita Hill from several miles distant. Furthermore, the enemy was able to reinforce his positions swiftly from Taveta some 11 kilometres away, allowing for a possible counter-attack. Beves pointed out that he was short of a battalion (the 8th SAI Battalion had not yet arrived) and requested a replacement battalion to bolster his exposed flank. Finally, he requested intensive artillery preparation and after that, the full cooperation of the artillery during the attack. He was fearful that artillery cooperation would not be possible in the event of a counter-attack launched by the Germans in the bush.63

However, Malleson placated Beves and gave him assurances that he would make adequate artillery support available and that the assault would be over before the Germans could launch an effective counter-attack. He was also confident that Belfield's Scouts, by conducting reconnaissance far in advance of the South Africans, would be able to alert them promptly of any enemy movement towards them that emanated from Taveta.64

As it turned out, there was little in the way of a combined arms approach because the artillery was unresponsive to the immediate needs of the infantry on the changing battlefield. Malleson reduced the role of the artillery to that of softening up the enemy positions on Salaita in an opening bombardment reminiscent of the "the Aldershot set-piece in three acts" applied in the Anglo-Boer War. For the main part, the artillery was unable to respond to the German counterattack and give support to the South Africans. Once the infantry became mobile on the right flank and the battle became fluid, the South Africans were unable to communicate effectively with the artillery to call for close support. The artillery also failed to respond and alter their bombardment when they discovered that the enemy's main defensive trench line was at the foot of Salaita rather than at the summit. The Boers used the same tactic at Magersfontein on 11 December 1899 against the British and the South Africans should not have been surprised at the position of the German trenches.65

The battle for Salaita Hill commences, 12 February 1916

The two brigades set off at dawn on 12 February from the Serengeti camp (see Table 2). They reached the Njoro riverbed 2½ kilometres apart at 06:45 and there were issued with orders for the attack. Malleson envisaged enveloping Salaita Hill from the north while Belfield's Scouts and two armoured cars guarded the right flank, and the mounted infantry and a further two armoured cars guarded the left flank of the South Africans. The Pioneers deployed in the riverbed to improve ramps and search for mines.66 The South Africans positioned themselves to the northwest of Salaita, when an hour later, two reconnaissance planes reported a sighting of newly dug German trenches, which extended northwards from the hill.67 The diary entry of an eyewitness, E.S. Thompson, brings the moment to life.

Reveille 0230. Marched on to the road and waited for daylight when we advanced and struck off to the right through the bush. After we had advanced about an hour we halted and an aeroplane came flying overhead and flew round the fort. We again advanced and when we had gone about 400 yards [366 metres] Jock Young found that he had left his rifle behind and went back to get it but couldn't find it. We still advanced with the 6th Regiment on our right and the Armoured Motors and Headquarters Staff on our left. We had advanced into an open space when suddenly we heard shells whistling over our heads and bursting about 30 yds [28 metres] behind us. At first there was a momentary pause then we all scampered for cover and a few more shells came along. For my part I was too excited to be frightened. After 5 minutes we were given the order to advance through the bush. Our howitzers now began firing and it was a fine sight, seeing the shells bursting round the trenches. When we got closer up they began firing at us with rifles so we got into cover and unpacked the guns. We kept on advancing and then the wounded began coming back.68

The South Africans continued their march and at 08:00, the 5th, 6th and 7th,SAI battalions deployed 1 000 metres from the northwest of Salaita Hill (see Map 3). The artillery came into action at 09:00 and began to bombard the German positions on the top and slopes of the hill. The artillery fire was mostly ineffective because the Germans occupied the trenches on the base of the hill rather than on its slopes.69 The 7th battalion halted some 500 metres from the German entrenchments at the base of the hill and began to take effective fire from the partially cleared fields of fire.70 Beves, in response, sent his 6th battalion to extend his line and thus develop the enveloping movement on his right. He kept the 5th battalion and his four remaining mountain guns in reserve. Beves lost touch with his mounted troops (Belfield's Scouts) as they disappeared out of sight to the north.71 Captain James commanded the machine gun battery, which Malleson attached to the South Africans for the day. He reported, after the battle, that the South Africans did not build up a proper firing line and the men were reluctant to open fire because of the enemy attention it would attract.72

The attack hardly came as a surprise to the Germans who noticed the preparations as early as 9 February. One of these was an abortive reconnaissance in force against Salaita made by the 2nd Rhodesian Regiment and the 130th Baluchis and artillery elements on 3 February 1916.73 The attack involved two South African regiments in support, as well as an artillery barrage on the fort at Salaita at the top of the hill. On 5 February the 6th South African Infantry Regiment (SAIR) made another reconnaissance and drew fire from Salaita.74 On the 9 February, the entire South African Brigade demonstrated in front of Salaita.75 It is not surprising that after all the British activity, which included numerous aircraft overflights, the Germans suspected an attack in the area.76

The element of surprise, often the factor in war that gives the attacker the edge, was lost. The overflights and various reconnaissance missions and demonstrations undertaken in the days before the attack had alerted the enemy on Malleson's interest in the outpost. Salaita's dominant position also afforded the defenders a good observation post where they were able to spot an enemy attack a good distance away, giving them time to reinforce the position. The artillery barrage undertaken in the vain attempt to soften up the enemy defences would also alert the Germans prematurely that an attack was underway. It was always going to be a difficult ask to try and achieve the element of surprise and the better solution was perhaps the one Smuts instituted a month later when he bypassed the stronghold and forced the Germans to abandon it. Smuts revealed his attitude and Boer way of war in the simple sentence he delivered when he visited the area on 20 February 1916. He climbed a tree, surveyed the enemy territory and said: "No necessity to attack Salaita."77

At approximately 09:00, the Germans realised that the British were launching a fully-fledged attack and were not a merely demonstrating. The Germans quickly identified that the main attack was developing in the north and was descending on the flank. They immediately responded and Major Georg Kraut ordered the 15 FK to position themselves to attack the South African right wing at 09:15. Captain Shulz did not need any orders and he acted on his initiative. He began to advance with three companies to meet the South Africans. Kraut issued the order for Shulz to attack at 10:00. In the face of mounting casualties, Beves now ordered his 7th SAIR to fall back at about 13:0078, at almost the same time that the Germans launched a counter-attack against the 6th SAIR with their 15th FK. The usual German aggression accompanied their attack. The arrival of the Germans to the right of the South Africans threatened to envelop their exposed wing.

To counter this, Beves sent forth his 5th SAIR to form a defensive flank. However, the 5th SAIR soon found itself outflanked in turn by the arrival of the 6th, 9th, and 24th FKs under the command of Shulz. The warning by Belfield's Scouts of the new German counter-attack developing came too late for the 5th SAIR and took the South Africans completely by surprise.79 In the face of the unexpected German attack, the South Africans began to give up ground and retreated in what was to become essentially a rout.80 The Germans regrouped at 14:00 and once again went on the attack, pursuing the retreating South Africans relentlessly, only to be stopped by the resilient defence of the 130thBaluchis.81 It was 130th Baluchis who successfully covered the ignominious South African retreat by resisting a bayonet attack and restoring order to the British front.82

What had developed on the South African flank was a classic encounter battle or a meeting engagement where the opposing sides collided in the field, incompletely deployed for battle. All indicators point to the fact that the South Africans were preparing to assault fixed entrenched positions on the northwest flank of Salaita. They were surprised to see the Germans had abandoned their trenches and that they were perhaps even dummy positions. What transpired instead was a manoeuvre battle where each side tried to extend its flank to meet the enveloping enemy. It was a battle in which the Germans held all the advantages. Their emphasis on devolving decision making down to the lowest levels of command (Auftragstaktik) allowed junior officers to make on-the-spot decisions. The decisive factors in these types of battle are the initiative of the junior officers and the calmness and efficiency of the troops. German training encouraged their troops, when they were in doubt, to make for where the sounds of battle are the loudest and charge aggressively in that direction immediately. The Germans were veterans of many battles while the South Africans were newcomers to war in East Africa. Once the Germans had derailed the South Africans from their set-piece attack by appearing on their flank, the South Africans became unhinged, then broke in the face of incessant aggressive attacks, and then ran.

The battle for Salaita exposed the weak C3I83 that plagued all the phases and levels of the operation. They seem to be little coordination of efforts between the two brigades and it is inexplicable that Malleson only put the East African Brigade into action after the South Africans had been in a battle for over four hours.84 The South Africans had no communication with Divisional Headquarters or with the East African Brigade and they were unable to direct the artillery fire to support them.85 Beves lost control over his forces once the situation became fluid on the British right. The South African retreat turned into panic and then into a rout. Retreating in the face of an aggressive enemy takes great skill and coordination and Beves would have done better if he had rather ordered his regiments to attack instead of retire.

Meanwhile, at 10:45 the 1st East African Brigade was sent forward. The British inexplicably held it back up to this point, supposedly to support the South Africans if necessary. Their advance soon halted after emerging from the bush into comparatively open ground 1 000 meters in front of the German trenches. There they came under heavy fire. Confronted with the well-placed German defences they were unable to make any further progress forward.87 At 12:00 orders were received to move the entire East African Brigade to the north to assist the South Africans in their northeast attack. Before elements of the brigade could complete the manoeuvre, a countermanding order was issued to attack Salaita directly.88 It seems that Malleson intended the East African Brigade to attack only once the South African attack was well underway, according to one regimental history. They lay in their positions for more than an hour "subject to heavy shell and searching rifle fire". They were waiting for the South African flank attack to develop before advancing themselves. When eventually the order to move forward was given at 13:00,89 there was a reluctance resulting in hesitation to move out of their relatively safe positions to ones that were closer to the enemy and far more vulnerable to their fire. Lieutenant-Colonel A. Capell, commanding the 2nd Rhodesian Regiment, objected to a verbal instruction to move forward and asked for written orders. At that stage, it became apparent that the flank attack had failed, and the Rhodesian Regiment began to retreat.90

The last word describing the trauma inflicted on the South Africans is left for E.S. Thompson who graphically describes the impossible chaos of the action and the fog of war surrounding the battlefield:

The 5th Regiment then began to retire and acted disgracefully, refusing to halt and lie down when ordered. Our Corporal then told us to retire right back so we retired till they began shelling us again so we lay flat down. It was at this point that I last saw Jock and Bob Thompson. We retired further and got behind some tall trees but they again shelled us so we doubled across an open space to the right and got in amongst the Indian Mountain Battery. We lay down for about half an hour with bullets zipping past all the time. The firing seemed to be coming nearer, then the 6th retired behind us so we retired right back and then to the right. … then the Baluchis who were guarding our rear got behind us so we retired further and got behind some trees but they began shelling us again so we got right out of it. By this time, I had finished my water and was terribly thirsty and tired. Several men of 'D' Company of the 7th got into the first line of trenches but as the 5th would not support them had to evacuate the place. Hans Gosch was killed during the retreat. He was bending over when he was shot through the back, the bullet coming through his jaw and smashing it. Everybody reckons that although it was a very hard position to storm we would have won had it not been for the 5th retiring. On reading this entry recently, I would say that we had been rather harsh about the behaviour of the 5th SAI. As far as I recall it was a case of a few young chaps going into a panic and that should not be interpreted as a reflection of the whole regiment.91

According to Malleson, Beves, who narrowly escaped capture, was apologetic and told him, "I don't know what to say for letting you in (sic) like this; I can only deeply apologise. My men have gone; it is impossible to rally them here. I am very sorry." Malleson describes the South Africans he encountered as being without discipline and cohesion and the officers appeared helpless. Malleson reported that several other officers, beside Beves, approached him the next day and apologised profusely for their poor conduct and said that the men were, "kicking themselves with shame and disgust".92

The fiasco cost the South Africans 139 casualties in a matter of four hours of combat, whereas they incurred 288 casualties in the entire German South West African campaign.93 German losses were considerably less with one German, 6 Askari and 3 carriers killed and 3 Germans, 22 Askari and 8 carriers wounded. The Germans captured a considerable amount of booty including 40 000 cartridges, 14 7cm artillery shells and 14 mules.94 The final scorecard fairly reflected the scale of the defeat inflicted on the South Africans.

An obviously shaken Tighe took four days to report the defeat to the Chief of Imperial General Staff, Lord Kitchener.95 Kitchener, fully understanding the possible political repercussions for South Africa, censured Tighe. He cautioned him not to take premature operations that would deprive the newly appointed commander of the East African forces, General Smuts, of full liberty of action before his arrival.96 After his arrival in GEA shortly after the Battle of Salaita, Smuts did not take immediate action against Tighe or Malleson. He gave both men another opportunity to prove their worth. Smuts sought and received permission to carry out the operation before the rainy season on 25 February. Smuts whitewashed the defeat at Salaita in his despatch by saying that the South Africans had learnt "invaluable lessons".97 Back in South Africa, Botha did his best to keep the full extent of the fiasco out of parliament.98

Smuts launched an attack on 5 March 1916, a mere three weeks after his arrival on 19 February. His wide enveloping movement forced the Germans to abandon Salaita Hill with hardly a shot fired. During the afternoon of 11 March, the British launched an attack, which took them to the foot of the Latema-Reata hills where were enemy gunfire held them up. Malleson, the commander at Salaita, apparently suffering from dysentery and perhaps a dose of uncomfortable déjà vu, chose to report sick.99 Tighe took over the command from Malleson. In the aftermath of the battle, these two generals were relieved of their command by Smuts who could barely conceal his contempt of their performance.100

Conclusion

South Africa, perhaps more so than the other belligerents, possessed an acute sensitivity to the political situation on the home front. Therefore, the divisive politics within her borders shaped her war policy and strategy. One could go as far as to say that South Africa's politics moulded her strategy, operational art, and even her tactics. Politics affected the conduct of the war in some key areas. Furthermore, the anti-British sentiments of the Afrikaner nationalists at home made her particularly sensitive to excessive casualties.

The plan of attack on Salaita Hill was the product of an age-old British doctrine, inculcated in Malleson, which favoured frontal assaults and believed that elan, esprit de corps and superior morale could gain the ascendency over an enemy's defensive firepower. The UDF, its doctrinal roots being an amalgamation of Boer, colonial and British systems, possessed a distinctly different way of war. The UDF favoured a war of manoeuvre and using the mobility of mounted infantry; they preferred to outflank or envelope an enemy rather than become involved in a costly frontal assault. The UDF, as demonstrated in their highly successful campaign in GSWA in 1915, chose to manoeuvre before engaging with the enemy, while the British, tied into their large logistic needs, fought in order to manoeuvre. The British preference for a direct frontal assault rather than a South African predilection for an operational enveloping movement, led to a clash of doctrine, which cost the South Africans dearly at Salaita.

REFERENCES

Anderson, R., 'JC Smuts and JL van Deventer: South African Commanders-in-Chief of a British Expeditionary Force', Scientia Miltaria, 31,2(2003). [ Links ]

Army Council, Field Service Regulations: Operations (His Majesty's Stationery Office, Edinburgh, 1909). [ Links ]

Baily, J., The First World War and the Birth of the Modern Style of Warfare (Strategic and Combat Studies Institute, Camberley, 1996). [ Links ]

Beca, Colonel, A Study of the Development of Infantry Tactics (George Allen & Unwin, London, 1915). [ Links ]

Boell, L., Die Operationen in Ost-Afrika (Walther Dachert, Hamburg, 1951). [ Links ]

Callwell, C.E., Small War: A Tactical Textbook for Imperial Soldiers (Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1896). [ Links ]

Capell, A. E., The Second Rhodesia Regiment in East Africa (The Naval & Military Press, Uckfield, 2006). [ Links ]

Citino, R.M., Death of the Wehrmacht: The German Campaigns of 1942 (University Press of Kansas, Kansas City, 2007). [ Links ]

Citino, R.M., The Path to Blitzkrieg: Doctrine and Training in the German Army, 1920-39, (Stackpole, Mechanicsburg, 1999). [ Links ]

Collyer, J.J., The South Africans with General Smuts in German East Africa (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1939). [ Links ]

Combined Training (War Office, London, 1905). [ Links ]

Crowe, J.H.V., General Smuts' Campaign in East Africa (John Murray, London, 1918). [ Links ]

Fendall, C.P., The East African Force 1915-1919: The First World War in Colonial Africa (Leonaur Publishing, Driffield, 2014). [ Links ]

Fuller, J.F.C., The Foundations of the Science of War (US Army Command & General Staff College Press, Kansas City, 1993). [ Links ]

Garcia A., "Manoeuvre Warfare in the South African Campaign in German South West Africa during the First World War", MA dissertation, University of South Africa, 2015). [ Links ]

Halder, F., Analysis of U.S. Field Service Regulations, MS No. P-133 (Historical Division, United States Army, Europe, 1953). [ Links ]

Hancock, W.K. and Van der Poel, J. (eds), Selections from the Smuts Papers, Vol III, July 1910-November 1918 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1966). [ Links ]

Hordern, C., Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, August 1914-September 1916 (His Britannic Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1941). [ Links ]

Hyam, R. and Henshaw, P., The Lion and the Springbok: Britain and South Africa since the Boer War (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003). [ Links ]

Hyam, R., The Failure of South African Expansion, 1908-1948 (Macmillan, London, 1972). [ Links ]

Hyam, R., Understanding the British Empire (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010). [ Links ]

Infantry Training (Provisional) (War Office, London, 1902). [ Links ]

Jones, S., "The Influence of the Boer War (1899-1902) on the Tactical Development of the Regular British Army, 1902-1914", PhD thesis, University of Wolverhampton, 2009. [ Links ]

Katzenellenbogen, S., South Africa and Southern Mozambique: Labour, Railways, and Trade in the Making of a Relationship (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1982). [ Links ]

Meinertzhagen, R., Army Diary, 1899-1926 (Oliver & Boyd, London, 1960). [ Links ]

Paice, E., Tip and Run (Phoenix, London, 2008). [ Links ]

Pakenham, T., The Boer War (Futura, London, 1982). [ Links ]

Sampson, P.J., "The Conquest of German East", in The Nongquai Special Commemoration Issue (Argus, Pretoria, 1917). [ Links ]

Shy, J., "First Battles in Retrospect", in Heller, C.E., and Stofft, W.A. (eds), America's First Battles, 1776-1965 (University Press of Kansas, Kansas City, 1986). [ Links ]

Stapleton, T.J., A Military History of South Africa from the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid (Praeger, Santa Barbara, 2010). [ Links ]

Thompson, E.S., "A Machine Gunner's Odyssey through German East Africa: The Diary of ES Thompson, Part I, 17 January to 24 May 1916", South African Military History Journal, 7,4(1987). [ Links ]

Uys, I., South African Military Who's Who, 1452-1992 (Fortress, Germiston, 1992). [ Links ]

Van der Waag, I., A Military History of Modern South Africa (Jonathan Ball, Cape Town, 2015). [ Links ]

Van der Waag, I., "Boer Generalship and the Politics of Command", War in History, 12,1 (2005). [ Links ]

Van der Waag, I., "Smuts's Generals: Towards a First Portrait of the South African High Command, 1912-1948", War in History, 18,1(2011). [ Links ]

Van der Waag, I., "South African Defence in the Age of Total War, 1900-1940", Historia, 60, 1(2015). [ Links ]

Von Lettow-Vorbeck, P.E., My Reminiscences of East Africa (Hurst & Blackett, London, 1920). [ Links ]

Watt, J., "The Eye of Revelation" available at <http://jr-books.com/EoR-Article-101115-MallesonPhoto.html> (Accessed 16 June 2016). [ Links ]

* He is working on "General J.C. Smuts and his First World War". His email address is dkatz@icon.co.za. My thanks to Evert Kleynhans and Will Gordon for assisting me in formulating the Afrikaans abstract.

1 . The South Africa Act of 1909 states this quite blandly in its preamble: "Whereas it is desirable for the welfare and future progress of South Africa that the several British colonies herein should be united under one government in a legislative union under the crown of Great Britain and Ireland."

2 . Ian van der Waag has produced a unique body of work dealing with the formation of the UDF. See I. van der Waag, "Smuts's Generals: Towards a First Portrait of the South African High Command, 1912-1948", War in History, 18,1(2011); I. van der Waag, "South African Defence in the Age of Total War, 1900-1940", Historia, 60,1(2015); I. van der Waag, "Boer Generalship and the Politics of Command', War in History, 12,1(2005). Another work that has merit on the formation of the UDF is T.J. Stapleton, A Military History of South Africa from the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid (Praeger, Santa Barbara, 2010).

3 . I. van der Waag, A Military History of Modern South Africa (Jonathan Ball, Cape Town, 2015), pp 83, 84.

4 . Stapleton, A Military History of South Africa, pp 113-118.

5 . A. Garcia, "Manoeuvre Warfare in the South African Campaign in German South West Africa during the First World War", MA dissertation, University of South Africa, 2015. Garcia presents an insightful study on the GSWA campaign.

6 . South African expansionism is a subject that historians have yet to explore fully. Hyam and Katzenellenbogen have done sterling work in broaching the subject. See R. Hyam, and P. Henshaw, The Lion and the Springbok: Britain and South Africa since the Boer War (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003); R. Hyam, The Failure of South African Expansion, 1908-1948 (Macmillan, London, 1972); R. Hyam, Understanding the British Empire (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010); and S. Katzenellenbogen, South Africa and Southern Mozambique: Labour, Railways, and Trade in the Making of a Relationship (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1982).

7 . J. Shy, "First Battles in Retrospect", in C.E Hellere and W.A Stofft (eds), America's First Battles, 1776-1965 (University Press of Kansas, Kansas City, 1986).

8 . (Author's emphasis) This definition owes its derivation in part to the Canada Department of National Defence, "The Conduct of Land Operations", B-GL-300-001/FP-000, 1998.

9 . J. Baily, The First World War and the Birth of the Modern Style of Warfare (Strategic and Combat Studies Institute, Camberley, 1996), p 48.

10 . T. Pakenham, The Boer War (Futura, London, 1982), p 128. Meinertzhagen admits that he has no understanding of manoeuvre warfare, which is not surprising, in the light of the British predisposition for the Aldershot way of war.

11 . Infantry Training (Provisional) (War Office, London, 1902).

12 . Infantry Training (Provisional), p 146. See also S. Jones, "The Influence of the Boer War (1899-1902) on the Tactical Development of the Regular British Army, 1902-1914", PhD thesis, University of Wolverhampton, 2009, p 51.

13 . Jones, 'The Influence of the Boer War, p 43.

14 . Army Council, Field Service Regulations: Operations (His Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1909).

15 . Combined Training (War Office, London, 1905), pp 100, 101). See also Jones, 'The Influence of the Boer War, pp 65, 66. [Colonel] Beca, A Study of the Development of Infantry Tactics (George Allen & Unwin, London, 1915), discusses the overturning of the defensive tendencies brought about by the Boer War that are reflected in Infantry Training 1902. He maintains that the new training manuals reverted to "a thoroughly offensive spirit" and that "… it is hoped that the attack with its strong moral backing will always remain the bedrock of our training", pp ix, x.

16 . Differences in conditions between southern Africa and Europe consisted of the abnormally good visibility in Africa compared to Europe, the large distances, poor infrastructure, different weather patterns and local terrain features which included the semi-arid nature of the battlefield.

17 . F. Halder, Analysis of U.S. Field Service Regulations, MS No. P-133 (Historical Division, United States Army, Europe, 1953). Halder defined German leadership as a capacity for independent action and a willingness to shoulder responsibility with a moral obligation to adhere to the mission and an ability to make complete clear and unambiguous decisions to establish a point of main effort.

18 . Robert Citino has contributed greatly to the understanding of the German way of war. See R.M. Citino, The Path to Blitzkrieg: Doctrine and Training in the German Army, 1920-39 (Stackpole, Mechanicsburg, 1999); and R.M. Citino, Death of the Wehrmacht: The German Campaigns of 1942 (University Press of Kansas, Kansas City, 2007).

19 . R. Meinertzhagen, Army Diary, 1899-1926 (Oliver & Boyd, London, 1960), p 166.

20 . Colonel Callwell offered his famous description of the Boers just prior to the outbreak of war, as well-armed, educated and led by men of knowledge and repute but "merely bodies of determined men, acknowledging certain leaders, drawn together to confront a common danger". See C.E. Callwell, Small War: A Tactical Textbook for Imperial Soldiers (HMSO, London, 1896), p 27.

21 . In Meinertzhagen's view, "The Dutch mounted brigade should do us well, for the men's physique is splendid and their morale high." See Meinertzhagen, Army Diary, p 164.

22 . Anderson is less than complimentary about the UDF (Smuts's) way of war. In this he differed very little from the consensus among British generals of the time, and most contemporary British historians. See R. Anderson, 'JC Smuts and JL van Deventer: South African Commanders-in-Chief of a British Expeditionary Force', Scientia Miltaria, 31, 2(2003).

23 . The National Archives UK, Kew (hereafter TNA), War Office (hereafter WO) 106/310 f17 (1), Smith-Dorrien, "Appreciation of the Situation in East Africa", 1 December 1915. The railway from Mombasa to Nairobi received particular attention from the Germans.

24 . TNA, WO 106/310 f20, "General Staff Appreciations, Future Conduct of the War", 16 December 1915.

25 . The Germans also occupied Nakob briefly; this was a border post on the northern Cape/GSWA border.

26 . TNA, WO 106/310 f20, "General Staff Appreciations, Future Conduct of the War", 16 December 1915.

27 . Meinertzhagen, Army Diary, pp 108, 123, 149, 153.

28 . TNA, WO 141/62 f15, J.C. Smuts, "Precis: Colonel Malleson", 15 March 1916.

29 . National Defence Force Documentation Centre, Pretoria (hereafter DOCD), 3rd South African Infantry Brigade, Box 6, Report of Lieutenant-Colonel A.M. Hughes and Lieutenant-Colonel Dirk van Deventer, 26 November 1915.

30 . TNA, WO 95/5345/15 f59, War Diary, 130th King George's Own Baluchis, Report on the Action at Mbuyuni, 14 July 1915.

31 . C. Hordern, Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, August 1914-September 1916 (His Britannic Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1941), p 156.

32 . A.E. Capell, The Second Rhodesia Regiment in East Africa (Naval and Military Press, Uckfield, 2006), p 30. Lieutenant-Colonel Capell was commander of the 2nd Rhodesia Regiment.

33 . National Archives Record Services of South Africa, Pretoria (hereafter NARSA), Jan Smuts Papers (hereafter JSP), A1 Box 390, Malleson Papers on Salaita Hill Engagement in East Africa Campaign, 1916-1918, "Notes on the Action at Salaita", Appendix III. See also TNA, WO 106/310 f20, General Staff Appreciations, Future Conduct of the War, 16 December 1915. The attack was in terms of a general vision for the theatre drawn up in December 1915.

34 . Hordern, Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, p 230.

35 . J.J. Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts in German East Africa (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1939), p 52.

36 . Hordern, Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, p 230. Major-General Michael Tighe replied in response to a query from Smith-Dorrien on the 7 February that he would attack Salaita between the 12 and 14 February.

37 . TNA, WO 95/5345/15 f11, War Diary 130th King Georges Own Baluchis, 29 March 1915. Casualties were 14 killed, wounded and missing; 2 machine guns had to be abandoned.

38 . Hordern, Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, pp 143,144. See also Meinertzhagen, Army Diary, p 122.

39 . NARSA, JSP, A1 Box 390, Malleson Papers on Salaita Hill Engagement in East Africa Campaign, Official Report on the Action at Salaita Hill, 12 February 1918, Appendix II. Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 55, emphasises the high expectation of a German counter-attack.

40 . TNA, WO 95/5345/12 f55, War Diary 1st East African Division, Operation Order no. 2, 11 February 1916.

41 . E. Paice, Tip and Run (Phoenix, London, 2008), p 177. The South Africans began arriving on 19 January 1916.

42 . Hordern, Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, p 231.

43 . NARSA, JSP, A1 Box 390, Malleson Papers on Salaita Hill Engagement in East Africa Campaign, 1916-1918, Official report on the action at Salaita Hill, 12 February 1918, Appendix II.

44 . J. Watt, "The Eye of Revelation" available at <http://jr-books.com/EoR-Article-101115-MallesonPhoto.html> (Accessed 16 June 2016).

45 . Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, pp 58, 59.

46 . Paice, Tip and Run, p 177.

47 . J.F.C. Fuller, The Foundations of the Science of War (US Army Command & General Staff College Press, Kansas City, 1993). Fuller set out nine basic principles of warfare in his book. These have seen some variation over time. They are i) Aim/Objective: Setting an aim with a clear set of measurable objectives; ii) Concentration: Point of maximum effort or focal point to meet the objective; iii) Offensive: Gain and maintain the initiative. Dictate the time, place, purpose, scope, intensity, and pace of operations; iv) Economy of Force: Direct bulk of resources to primary objective and minimum of combat power on secondary objectives; v) Surprise: Strike at a time or place or in a manner for which the enemy is unprepared; vi) Manoeuvre/Mobility: Outmanoeuvre the enemy using superior mobility and flexibility; vii) Security: Protect operations from enemy actions; viii) Simplicity: Avoid unnecessary complexity in preparing, planning, and conducting military operations; and ix) Unity of Command: Unity of effort for every objective under one responsible commander.

48 . DOCD, Personnel File, P.S. Beves, Record of Service. Beves died on 26 September 1924 of complications due to the malaria he contracted while serving in German East Africa.

49 . I. Uys, South African Military Who's Who, 1452-1992 (Fortress, Germiston, 1992), p 18; Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 54. Beves had served as a captain in the Boer War in a regular British infantry regiment and thereafter commanded the Transvaal Volunteer Force until 1912, when he became commandant of cadets in the UDF.

50 . NARSA, JSP, A1 Box 390, Malleson Papers on Salaita Hill Engagement in East Africa Campaign, 1916-1918, Notes on the action at Salaita, Appendix III.

51 . Paice, Tip and Run, p 177. The South Africans began arriving in German East Africa on 14 January 1916 and were in action at Salaita a mere four weeks later.

52 . NARSA, JSP, A1 Box 390, Malleson Papers on Salaita Hill Engagement in East Africa Campaign, 1916-1918, Official report on the action at Salaita Hill 12 February 1918, Appendix II.

53 . P.E von Lettow-Vorbeck, My Reminiscences of East Africa (Hurst & Blackett, London, 1920), pp 79, 80.

54 . NARSA, JSP, A1 Box 390, Malleson Papers on Salaita Hill Engagement in East Africa Campaign, 1916-1918, Notes on the action at Salaita, Appendix III.

55 . Hordern, Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, p 230; Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 54. See also P.J. Sampson, "The Conquest of German East", in The Nongquai Special Commemoration Issue (Argus, Pretoria, 1917), where Sampson writes: "The trenches on the hill itself appear to have been devised for the sole purpose of misleading our airmen and intelligence men generally", p 14.

56 . TNA, WO 95/5345/12 f42 War Diary, 1st East African Division, Operation Order no. 1, 2 February 1916. The operation order estimates 200 enemy and 2 Maxim machine guns defending Salaita on 2 February. See also Hordern, Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, p 231.

57 . NARSA, JSP, A1 Box 390, Malleson Papers on Salaita Hill Engagement in East Africa Campaign, 1916-1918, Official report on the action at Salaita Hill, 12 February 1918, Appendix II. See also TNA, WO 95/5345/12 f47, War Diary 1st East African Division, Operation Order no. 4, 6 February 1916. German strength in and around Taveta was estimated as not exceeding 3 000.

58 . NARSA, JSP, A1 Box 390, Malleson Papers on Salaita Hill Engagement in East Africa Campaign, 1916-1918, Notes on the action at Salaita, Appendix III.

59 . The table is derived from Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, pp 53, 54.

60 . On inspecting the hill some weeks later, it was found that: "The hill was practically impregnable with concrete gun emplacements and rifle pits beautifully concealed, barbed wire entanglements and, of course, plenty of dummy trenches…" See Sampson, 'The Conquest of German East', p 14. See also J.H.V. Crowe, General Smuts' Campaign in East Africa (John Murray, London, 1918), p 56. The Germans prepared for an all-round defence of Salaita.

61 . DOCD, 3rd South African Infantry Brigade, Box 6, Report of Captain Frank Douglas, 17 December 1915. References to the South African troops' tendency to denigrate and dismiss the fighting qualities of "native" troops, friend or foe, appear in many of the secondary sources. This primary source gives credence to the notion that the South Africans were indeed dangerously dismissive before the Battle of Salaita Hill. See also C.P. Fendall, The East African Force 1915-1919: The First World War in Colonial Africa (Leonaur Publishing, Driffield, 2014), p 40.

62 . Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, pp 54, 55.

63 . Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 55.

64 . Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 55.

65 . The Boers entrenched their forces at the foot of the hills rather than the forward slopes, as was the accepted practice.

66 . DOCD, War Diary of 2nd South African Infantry Brigade, 3 February 1916, WWI GSWA, Box 77. See also Paice, Tip and Run, p 180.

67 . NARSA, JSP, A1 Box 390, Malleson Papers on Salaita Hill Engagement in East Africa Campaign, 1916-1918, Official report on the Action at Salaita Hill, 12 February 1916, Appendix II. See also Hordern, Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, p 232. Collyer attests to the ineffectiveness of the artillery in silencing the German machine guns when he writes that "the enemy positions were most cunningly concealed". See Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 13.

68 . E.S. Thompson, "A Machine Gunner's Odyssey through German East Africa: The Diary of ES Thompson, Part I, 17 January to 24 May 1916", South African Military History Journal, 7, 4 (1987).

69 . Sampson writes: "The enemy forces apparently were not on the hill at all, but in a cleverly constructed trench among the bush at the very foot of the hill. The searching bombardment of the hill by our guns, therefore had no effect, and it is doubtful if any of our shells touched the enemy's real trenches at the foot of the hill." See Sampson, "The Conquest of German East", p 14.

70 . Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 56.

71 . Hordern, Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, p 232.

72 . TNA, WO 141/62 f6, Memorandum Colonel Malleson to Secretary of the Army, 6 July 1916.

73 . DOCD, "War Diary of 2nd South African Infantry Brigade", 3 February 1916, WWI GSWA, Box 77. See also Hordern, Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, p 230. A reconnaissance in force against Salaita was made by the 2nd Rhodesian Regiment and the 130th Baluchis and artillery elements on 3 February 1916. See Paice, Tip and Run, p 178. The South Africans were part of a reconnaissance undertaken on 3 February and 9 February when the whole brigade took part in a demonstration in front of Salaita Hill.

74 . DOCD, "War Diary of 2nd South African Infantry Brigade", 5 February 1916, WWI GSWA, Box 77.

75 . DOCD, "War Diary of 2nd South African Infantry Brigade", 5 February 1916, WWI GSWA, Box 77. The purpose of this adventure was to examine roads, and locating mines. The South Africans advanced up to 700 meters of the Salaita defences. See also TNA, WO 95/5345/12 f42, War Diary 1st East African Division, Operation Order no. 8, 8 February 1916. The main purpose of the probe according to the divisional operations order was to make the road over the Njoro Drift fit for every type of vehicle. The infantry advance was meant to create a diversion to cover the work of the engineers and the reconnaissance parties.

76 . L. Boell, Die Operationen in Ost-Afrika (Walther Dachert, Hamburg, 1951), p 139. See also Paice, Tip and Run, p 177; and Capell, The Second Rhodesia Regiment in East Africa, p 47.

77 . Capell, The Second Rhodesia Regiment in East Africa, p 53.

78 . Sampson, "The Conquest of German East", p 14.

79 . Hordern, Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, p 233.

80 . Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 57. Collyer admits that several platoons of the 7th SAI retired in disorder although no panic set in. See also Fendall, The East African Force, 1915-1919, p 40. The author describes the South Africans as "thoroughly scared".

81 . Boell, Die Operationen in Ost-Afrika, p 140.

82 . TNA, WO 95/5345/15 f146, War Diary 130th King Georges Own Baluchis, Appendix IV, 12 February 1916. See also Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 57; and Fendall, The East African Force. The South Africans are described as being "contemptuous", going as far as to express their disgust at having to serve alongside Indian soldiers.

83 . Command, Control, Communications and Intelligence. Command and Control is a system that empowers a commander to accomplish his mission by marshalling the resources, human and logistical to achieve his mission.

84 . Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 58.

85 . Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts, p 59.

86 . Collyer, The South Africans with General Smuts.

87 . TNA, WO 95/5345/15 f146, War Diary 130th King Georges Own Baluchis, Appendix IV, 12 February 1916. See also Hordern, Military Operations East Africa, Volume 1, p 233.

88 . TNA, WO 95/5345/12 f55, War Diary 1st East African Division, Operations against Salaita, 12 February 1916.

89 . TNA, WO 95/5345/15 f146, War Diary 130th King Georges Own Baluchis, Appendix IV, 12 February 1916.

90 . Capell, The Second Rhodesia Regiment in East Africa, p 48.

91 . Thompson, "A Machine Gunner's Odyssey".

92 . TNA, WO 141/62 f6, Memorandum from Colonel Malleson to Secretary of the Army, 6 July 1916.

93 . Van der Waag, A Military History of Modern South Africa, p 126.

94 . Boell, Die Operationen in Ost-Afrika, p 141.

95 . TNA, WO 33/858, M. Tighe, "Action at Salaita Hill", Telegram Tighe to Kitchener, 16 February 1916.

96 . TNA, WO 33/858, Kitchener, "Action at Salaita Hill", Telegram Kitchener to Tighe, 18 February 1916.

97 . TNA, WO 141/62 6128, Smuts Despatch on East Africa, 20 June 1916.

98 . W.K Hancock and J. van der Poel (eds), Selections from the Smuts Papers, Vol III, July 1910 -November 1918 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1966), p 337.

99 . Meinertzhagen, Army Diary, p 170. Meinertzhagen provides a little more illumination on the matter, recalling that Smuts had called Malleson a "coward". This was not a position that Meinertzhagen disagreed with.

100 . TNA, WO 32/5822, J.C. Smuts, "Operations in East Africa" (Memorandum Smuts to CIGS, 23 March 1916) p 73a. Smuts was anxious that Tighe's reassignment to the Indian Army was not considered in the same light as Malleson.