Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Historia

On-line version ISSN 2309-8392

Print version ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.60 n.1 Durban May. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8392/2015/v60n1a7

ARTICLES

Kruger's lost voice: Nation and race in pre-World War 1 Afrikaans music records

Schalk D. van der Merwe

Lectures in History at Stellenbosch University and is currently completing his PhD on identity in Afrikaans popular music. He recently published "Radio Apartheid: Investigating a History of Compliance and Resistance in Afrikaans Popular Music, 1956-1979", South African Historical Journal, 66, 2, 2014, pp 349-370. He also plays bass in various rock groups

ABSTRACT

On a theoretical level, popular music records serve as artefacts of the social and cultural networks in which their particular performers are embedded. Seen from this perspective, the appearance of the earliest Afrikaans gramophone records coincided with a crucial juncture in the formation of Afrikaner identity, as well as the development of the language itself. This article is a forensic investigation into the socio-political contexts in which the first Afrikaans gramophone records were produced. Its sources include updated discographic catalogues that have led to the discovery of listings of a number of recordings that pre-date the previously earliest known Africana and Afrikaans records. Most of the first Africana recordings were of the national anthems of the two Boer republics during and shortly after the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) and sung by Dutch singers. The first Afrikaans recordings by people beginning to define themselves as Afrikaners, date back to 1906, while local advertisements for Afrikaans records began to appear in 1910. This article will seek to explore the link between these recordings and claims for nationhood based on the linguistic identity of a key group of white Afrikaans speakers.

Key words: Afrikaans; Africana; gramophone records; identity; national anthems.

OPSOMMING

Op 'n teoretiese vlak funksioneer populêre musiek albums as artefakte van die sosiale en kulturele netwerke waaraan die kunstenaars gekoppel is. Gesien van uit hierdie perspektief, val die eerste Afrikaanse gramofoon plate saam met 'n belangrike stadium in die ontwikkeling van Afrikaner identiteite, asook die ontwikkeling van Afrikaans as taal. Hierdie artikel is 'n forensiese ondersoek wat fokus op die sosio-politieke kontekste waarin die eerste Afrikaanse gramofoon plate gemaak is. Bronne sluit in opgedateerde diskografiese katalogusse wat gelei het tot die ontdekking van lyste van opnames wat ouer is as die vroegste bekendste Africana en Afrikaanse plate. Die meeste van die eerste Africana opnames was van die nasionale volksliedere van die twee Boere republieke tydens, en kort na, die Anglo-Boereoorlog (1899-1902) en is gesing deur Hollandse sangers. Die eerste Afrikaanse opnames deur mense wat begin het omhulself te definieer as Afrikaners dateer uit 1906, terwyl plaaslike advertensies vir Afrikaanse plate begin verskyn in 1910. Hierdie artikel beoog om die verhouding tussen hierdie opnames en eise tot nasieskap, gebaseer op die linguistiese identiteit van 'n sleutelgroep Afrikaners, te verken.

Sleutelwoorde: Afrikaans; Africana; gramofoon plate; identiteit; nasionale volksliedere.

A brief exploration of the linguistic and musical development of Afrikaans

The development of the Afrikaans language was a major source of pride and one of the cornerstones of white Afrikaner nationalist mythology from the 1930s onwards.1 Claims of racial and linguistic purity, constructed to serve political ends, have long since been discarded in favour of ethno-linguistic explanations that are unencumbered by such agendas. The complex development of Afrikaans, had by the end of the nineteenth century, been some 250 years in the making and the distinct differentiation between the three original groups involved in this development - European settlers, the Khoikhoi, and imported Malay slaves - had eroded.2 This erosion, however, stopped short of true creolisation. Denis Constant-Martin, in his recent Sounding the Cape, provides a thoughtful exploration of the complexities of creolisation, hybridity and mettisage in the South African context.3 Common in the literature is the presence of racial oppression and power struggles that are more reflective of the colonial racial hierarchy than of a harmonious pluralistic society.4

A central theme was the historical racial dominance of Dutch colonists who imposed their language on imported slaves and indigenous local populations.5 The race-consciousness of whites, as well as the influence of the Dutch Statenbijbel in religious practices, limited the creole development of Afrikaans.6 Despite this racial hierarchy, the diverse historical origins were influential in establishing varying degrees of cultural differentiation among Afrikaans speakers. The language became the mother tongue of Christians and Muslims, of whites, coloureds and blacks, in the cities and on the farms, of workers and landowners. Its earliest written texts even appeared in two different alphabets - Arabic and Roman.7 It was, however, a specific group of white Afrikaans speakers that involved themselves intimately with establishing a linguistic identity that denied its mixed-racial roots:

Afrikaner identity was developed in a period when European civilisation was the model, and when everything African was stigmatised. In a context where Afrikaans was called a "Hotnot's language" or the bastardised language of "Asian and Mozambican maids" ... the supporters of the language reacted by emphasising the racial purity of the language. The racism which was made an element of the identity speaks of the way in which the African aspects of the identity were socially traumatised.8

The emerging white version of Afrikaans had to withstand the influence of the racial "other" to maintain its European cultural identity, whilst simultaneously resisting the challenges of British imperialism.9

The development of Afrikaans music was subject to similar social forces. Its diverse cultural heritage saw Afrikaans music sung in Afrikaans and played by musicians from across the racial spectrum.10 Imported Dutch and German songs (and some English) - hymnal and folk - left their mark, as did minstrel songs from America brought to the colony in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Here, it was translated and partially creolised into the emerging vernacular.11 Traditional boeremusiek especially represented a complex interactional aggregate between the urban and the rural, race and class, much like the language itself.12 Recorded Afrikaans music did not always reflect these processes. The technological development of the gramophone coincided almost perfectly with the emergence of the TweedeTaalbeweging (Second Language Movement) shortly after the Anglo-Boer War, and was instrumental in the codification of Afrikaans and Afrikaner cultural (and political) identities. This placed the first Afrikaans records among a wider constellation of cultural artefacts aimed at "building a nation from words".13

Sources

No official archive exists of the earliest Afrikaans music recordings and written sources are very limited. The Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie (South African Music Encyclopaedia, hereafter SAME),14is the most comprehensive and provides a detailed discography of early Africana and Afrikaans records between 1901 and 1938. One of the SAME's main sources is Roberto Bauer's The New Catalogue of Historical Records, 1898-1908/09.15New information surfaces regularly, which means that such catalogues become outdated.16 More recently, the discographer Alan Kelly's research on the Gramophone Concert Company has provided invaluable information of the earliest years of the global recording industry.17 Since this company, along with its subsidiary labels HMV and Zonophone, was responsible for most of the earliest Afrikaans recordings, Kelly's catalogues are of major significance. It can be searched online at the AHRC Research Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music (CHARM) in the UK, established in 2004. The CHARM discography was especially useful in finding listings of early Afrikaans recordings in London that are older than those of Paul Roos' Springbok rugby team (from 1906), which were previously thought to be the first in Afrikaans, by Afrikaners.18 The Truesound Online Discography Project19 is another online archive with almost 400 000 matrix listings of early recordings. Here, the Zonopoint catalogue (again thanks to Kelly and updated in 2003) yielded matrix listings of a number of Afrikaner national anthems never before documented that pre-date the earliest mentioned in the SAME (Thomas Denijs' and Betsy Schot's recordings of 1901). Unfortunately, such catalogues are not organised according to language or title, which forces the researcher to go through hundreds of thousands of matrix listings with potentially very low yields.20 Another valuable source, especially for information on the 1912 South African recordings and later, is the South African Audio Archive, which features photographs and sound clips of old records sourced from private collectors.21 By consulting these various updated catalogues for previously unknown recordings and combining it with the existing information listed in the SAME, a more complete picture has emerged on early Afrikaans records. These new discoveries provide a unique opportunity - and a larger sample size - to explore the relation between recorded Afrikaans music and emerging Afrikaner identities at a critical phase of the development of Afrikaner nationalism.

The first recordings of Afrikaans music

According to Eric Rosenthal, the well-known photographer Arthur Elliott recorded the voice of Paul Kruger onto a crude cylindrical device, which was subsequently lost, and with it probably the first sound recording of the Afrikaans language.22 The recording must have been made sometime between 1890 (when Elliott arrived in South Africa) and 1900 (when he moved to Cape Town as a war refugee). However, it is doubtful whether it was a music recording, because Kruger was not known for his singing. The crude cylindrical device was most likely a phonograph,23 a technology that became outdated by the development of gramophone records thanks mostly to the work of German inventor, Erwin Berliner.24 From the late 1890s onwards, (the influential Gramophone Record Company, for example, was established in 189825), mobile gramophone recording units were sent across the globe to capture not just music, but many forms of folk culture. Studios in Europe and the US made numerous recordings of orchestral music and operas, but also lighter, popular, compositions and dialogues. On the choice of material, Kelly is of the opinion that:

... these records - the great majority - were made simply to give a little pleasure to their purchasers and to earn a few pence for the Company. However, even in the very earliest days, many records were made for more serious, even historical purposes.26

Of the tens of thousands of recordings made across the globe before 1905, only fifteen27 have an Afrikaans connection, and most of these have a reference to the Transvaal. The nineteenth-century wars between the two Boer republics and the British Empire seem to have been a source of inspiration for continental European composers and songwriters.28 During the second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) especially, pro-Boer sentiments led to the composition of popular songs from all over Europe, including Belgium, Holland, Russia, Hungary and Czechoslovakia.29 Trewhela mentions that the French were particularly inspired by the Boers, and songs like Marche Hérioque des Boers; 'Le Patriotisme des Boers; Boers, Je Vous Salue! and Hommage Aux Armeées Hérioiques des Republiques du Transvaal et d'Orange attest to this.30 Ludemann has written specifically on the Buren-Marsch, a German composition by August Bernhard Ueberwasser between 1901 and 1904, an apparent homage to the citizens of the two Boer republics that contains a whole section on the Transvaal anthem.31

These pro-Boer sympathies reflected anti-British feelings on the continent at the time, which resulted in a number of recordings of Afrikaner national anthems, sung for the most part by Dutch singers. The first were recorded in Den Haag and Berlin in January 1900. In Den Haag, the Transvaalsch Volkslied was recorded by J.C. van den Berg, while E. Spieksma recorded Transvaal en Nederland and Volkslied van den Oranje Vrijstaat32In Berlin, both Ewald Brukner and H. Cornelli made recordings of the Transvaalsch Volkslied.33As far as can be determined from discographic evidence, these recordings by Van den Berg, Spieksma, Brukner and Cornelli are the oldest Africana gramophone recordings and they pre-date the fall of the Transvaal (or Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek) in September 1900. More recordings followed after the fall. The Municipal Military Band recorded Boeren Nationale Hymne on 6 December 1900 in London.34 The Dutch soprano Betsy Schot recorded Transvaalisch Volkslied in Berlin on 30 August 1901.35 On 10 September 1901, the Kapel van het 7e Regiment Infanterie from Amsterdam recorded Het Transvaalsch Volkslied and Transvaalsch Vlaggenlied, while the Dutch baritone Thomas Denijs also recorded Het Transvaalsch Volkslied andTransvaalsche Vierkleur, in Amsterdam in the same month, although the exact day is unknown.36 Denijs was a classically trained opera singer, one of Holland's finest, and joined the Amsterdam Opera in 1901.37

Another version of the anthem was recorded in Brussels by Jan Teirlynck on 12 September 1902.38 The Transvaalsche Volkslied was written in 1875 by Catharina van Rees (who was Dutch), on request by President Burgers,39 and has the well-known opening lines: "Kent gij dat volk vol helden moed, En toch zo lang geknecht?"40It remained a popular anthem linked to Afrikaner nationalism throughout the twentieth century. Apart from this one anthem, other songs about the Transvaal were recorded in this early period. Jan Willekens recorded Vredelied over Transvaal on the same day, possibly in the same studio, that Teirlynck recorded the Transvaal anthem.41 A possible earlier recording, Wat zien we in Transvaal, was made in Brussels by Louis Verstraeten in either 1901 or 1902.42 The Dutch baritone, Arnold Spoel, recorded his own composition, Vereenigd Afrika, in Brussels in 1904.43 Spoel composed Vereenigd Afrika "Aan de helden der Transvaal" 44 in 1899, and presented it to Paul Kruger on his arrival in Den Haag in 1901 during his exile.45

Although these songs were all recorded by classically trained European (mostly Dutch) singers and not actually sung by Afrikaners, their direct relation to politics and the people of the Transvaal, offered support for Afrikaner independence. They also sub-textually highlighted tension between white Afrikaans speakers, precipitated by geographic and class differences:

In the early years of this century many "Afrikaners" maintained that Dutch and not Afrikaans was the language of the Afrikaner. In the Geref. Maandblad of Sept. 1905 a Prof. Marais said referring to Afrikaans: The kitchen language which is glorified in Pretoria ... is not the language of the cultured Afrikaner ... Therefore, to the Dutch-orientated Afrikaners Afrikaans had the image of being the language of the lower strata of society, of being a proletarian language or the language of a people fast becoming proletarianised in the cities. On the other hand the language was essential in the communication with and the mobilisation of the white Afrikaans-speaking working class.46

The link between early national anthems and the Afrikaner rural working class is strong. Jan Stephanus de Villiers composed many early Afrikaans psalms and hymns, as well as volksliedere like n leder Nasie (also known as Die Afrikaanse Volsklied) and Vlaggelied.47He was a close collaborator of S.J. du Toit of the Genootskap vir Regte Afrikaners (GRA), which was formed in 1875 as part of the First Language Movement.48 The GRA published Die Afrikaanse Patriot - the first Afrikaans newspaper, in Paarl, and appealed to Afrikaner nationhood and the acceptance of Afrikaans as a language.49 These early language pioneers stood opposed to the Dutch-speaking elites, who looked down on the Boers and resisted the acceptance of Afrikaans as a written language.50 De Villiers was responsible for setting to music texts by Du Toit, such as the Transvaalse Vrijheidslied in 1881, which was more popular among Transvalers than the official anthem, Kent gij dat Volk, by Van Rees.51 Van Rees' version was also sometimes known as the Volkslied van de Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, but is different from the Zuid-Afrikaansche Volsklied,52which can cause some confusion. Rautenbach mentions another Transvaalsch Volkslied that is not Kent gij dat Volk, and which originated in the Eerste Taalbeweging.53The lyrics display openly anti-British sentiments, with lines like "In vry Transvaal, bevry van Britse dwinglandy", "Britse verraad", "Haal ons die Britse roofvlag neer"54De Villiers composed Di Vierkleur van die Transvaal (also known as the Transvaalse Volkslied) in 1881, which is not the same composition.55

In the absence of the actual recordings, it is impossible to establish definitely whether the early recordings of Transvaalsch Volkslied are indeed Van Rees' version, or one of the other anthems also known as the Transvaalsch Volkslied, or if some recorded the former, while the other recorded the latter, which would mean that they are in fact Afrikaans and not Dutch, and will have an even more direct link to early Afrikaner nationalist ideals. Despite the fact that there exists confusion over the titles of some of the anthems, the fact that many were penned by people closely connected with the first Taalgenootskap, adds real political significance.56 Furthermore, a number of these anthems were later invoked during a new wave of Afrikaner nationalism when they were published in the first Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge (FAK) songbook in 1937. These early records were not, in a strict sense, popular music recordings and it is doubtful whether they were even on sale in South Africa. They were also -depending on which version of the Transvaal Volkslied - probably in Dutch, not Afrikaans.

The earliest undisputed recordings by Afrikaans-speakers in Afrikaans date to 1906 and were made in London. On 9 July a J.F. Smith recorded Transvaal Dialogue; Transvaal Volkslied; The Vine: Transvaal Recitation; Boer Melodies; Transvaal Volks: Paraphrase. J.F. Smith was likely actually J.J. Smith - as initials were often noted down incorrectly either by studio engineers or later discographers who had to decipher handwritten documents. There is evidence that J.J. Smith's initials were occasionally changed to "J.D." on later record listings.57 Smith recorded several Afrikaans dialogues in the following years in London and was in correspondence with the Gramophone Record Company on copyright issues regarding Afrikaans recordings of English hymns.58 Judging by his personal letters to his mother, he did not share the same anti-imperialist notions of many Afrikaners of his time. He preferred the English to the Dutch, and was at first a strong supporter of Louis Botha. This changed in the aftermath of Union, when his allegiance switched to Hertzog.59 Upon returning to South Africa after his studies in London, he became the editor of Die Huisgenoot in 1916. He also became the first ever professor in Afrikaans, at Stellenbosch University in 1919, where he happened to lecture a young Hendrik Verwoerd. Smith was also the first editor of the Woordeboek vir die AfrikaanseTaal (WAT).60 He was an important figure in the Second Language Movement.

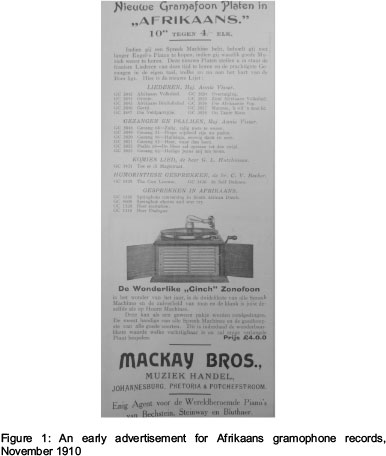

A few months after Smith's initial recordings, Paul Roos' Springbok rugby team (on tour to Britain in 1906) recorded Springbok Chorus and War Cry in London, released on the Gramophone Concert Record series.61 They also recorded Springboks Conversing in the Taal, Boer Recitation and Boer Dialogue.62 Recordings of spoken Afrikaans and references to the taal, became popular themes in later recordings, suggesting that Afrikaans was still something of a curiosity at the time. On Springbok Chorus and War Cry the rugby players sing My Matras en jou Kombers; Die Eenkant op die Anderkant af; Al Slaan my Ma my neer; and We are Marching to Pretoria.63The connection between sport and music remained strong throughout the history of recorded Afrikaans music. This record appears on what was likely the first advertisement for Afrikaans records (Figure 1) - by the Mackay Brothers Company64 in November 1910.65

It was for a collection of recordings done in London at the studios of the Gramophone Company between 1906 and 1910. The caption of the advertisement is revealing:

Indien gij een Spreek Machine hebt, behoeft gij niet langer Engelse Platen te kopen, indien gij waarlik goede Muziek wenst te horen. Deze nieuwe Platen stellen u in staat de fraaiste Liederen van dezetijdte horen en de prachtigste Gezangen in de eigen taal, welke zo aan het hart van de Boer ligt.66

The tension between English and Afrikaans underscored here is indicative of wider political tension between these groups six months into Union. The word "Boer" is also significant. The wording used in this advertisement (by an English company) is not coincidental. The influential linguist and Afrikaans language campaigner of the Second Language Movement, Gustav Preller, had the following to say about business opportunities aimed at the Afrikaners: "One of them is the practical businessman. If he wishes to reach the buying and commercial public, he tells the publishers of adverts, 'in Boer language, otherwise people won't understand'."67

Die Brandwag was launched in 1910 by the Afrikaanse Taalgenootskap (Afrikaans Language Society) as an important vehicle for language mobilisation in the wake of Union.68 Hofmeyr's perceptive analysis of the development of Afrikaans literary culture and its role in elaborating Afrikaner nationalist ideology brings into focus the way in which publications like Die Brandwag and Huisgenoot re-packaged all manner of everyday things as "Afrikaans".69 Advertisements like the one above, as well as the records advertised, formed part of this process of defining Afrikaner identity.

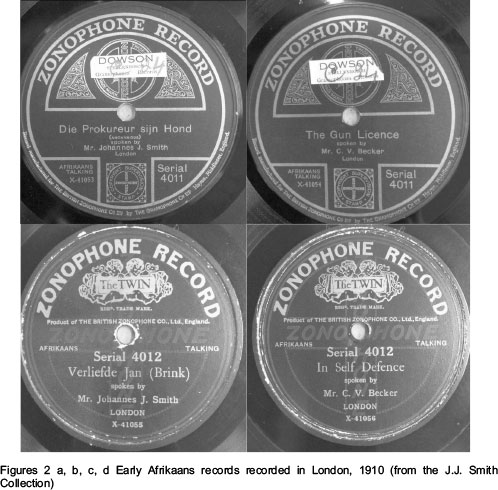

Of the 23 songs and dialogues, six are hymns and psalms, two are Afrikaner national anthems,70 eight are popular folk songs, three are humoristic songs/ dialogues (two of which have English titles), and four are recordings of the Springboks conversing and/or singing in "South African Dutch".71 As mentioned earlier, the gezangen were Afrikaans versions of English hymns, and not original. The two English titled dialogues by Clarence Vivian Becker are labelled as "Afrikaans talking" and appear on the flipside of two Afrikaans dialogues recorded by J.J. Smith.72 According to Trewhela, Becker started recording in 1908,73 although the SAMEs earliest entry dates to 1910, which corresponds with Kelly's catalogue.74 He did, however, have an earlier connection to Afrikaans recordings as he was one of the Springbok selectors of the 1906 tour, although it is unlikely that he accompanied them to Britain, since he does not appear in the team photos of the tour.75

The Afrikaans soprano Annie Visser features prominently in these recordings, which might account for the choice of material. Visser was born on the farm Lokshoek in the Jagersfontein district of the Free State Republic in 1876, the daughter of Gert Petrus Visser, who chaired the Volksraad for 19 years. Before the Anglo-Boer War, she studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London, but moved to Amsterdam because she "could not be a guest in a country against which her brothers were fighting".76 Her recording of the Zuid-Afrikaans Volkslied was made on the very same day of the formation of the Union of South Africa - 31 May 1910. The Union attracted international attention, which might have prompted the Gramophone Company to record such a commemoration.77

Visser was also a vocal supporter of Hertzog and his National Party.78 In an interview with the Natal Mercury she stated that she aimed at "... making the Dutchman proud of his language by singing about it and in it ... the Dutch people need stirring up in this way."79 Her life and career, and her Afrikaner patriotism, solicited new interest in the early 1960s when two articles about her appeared in Die Burger80and the Huisgenoot.81

Answering a public call for information on Visser's life, State President C.R. Swart himself responded with a letter in which he revealed a number of facts attesting to her close connection to the Afrikaner political elite of the early twentieth century. Visser apparently enjoyed a close relationship with the Hertzogs and often spent time at their home. She also sang at the inaugural congress of Hertzog's National Party in 1915, and was given the honour of choosing the colours of the new party (orange and white).82 Although Stegmann's accounts of Visser's patriotism date to the height of Afrikaner nationalist optimism, her proximity to Afrikaner nationalism of the early decades of the twentieth century is important. Also significant is that she features prominently as one of the earliest singers of popular Afrikaans songs on gramophone record.

Another seemingly patriotic Afrikaans singer was Joey Bosman, who, like Visser, received classical vocal training in England, possibly during the Anglo-Boer War. According to a July 1903 article in De Goede Hoop, Bosman once, during her three year stay there, responded to anti-Boer comments by calmly pinning a ribbon of the Vierkleur (the flag of the defeated Transvaal republic) to her chest.83 Apart from this article, no other references to Bosman could be found nor any indication that she recorded any music, since she returned to South Africa well before the first Afrikaans recordings.

Since Bosman was her maiden name, she could well have made later recordings under a different surname. Two Joey's come to mind: a Joey Marais recorded Danie en Lenie/ Nader mijn God bij U in London in 1910,84 while a Joey Stamrood recorded 14 songs, including Zuid-Afrika, in Cape Town in 1912.85 This is of course, pure speculation, but Bosman must have been a prominent enough singer to be featured in a printed article. The branding of Bosman and Visser as patriots reminds one of the manner in which Die Brandwag and Die Huisgenoot "fabricated a tremendous cult of personality around certain literary figures whom they depicted in personalised articles and full-page pictures."86

Kate Opperman recorded several songs including Het Volkslied van de Zuid-Afrikaanse Republiek, Het lied der Afrikaners and Volkslied van de Oranje-Vrystaat in London c. 1912-1913.87 Originally from Ladybrandt in the Free State, she won a scholarship and left for London in 1911. She apparently performed at the Albert Hall, the Queen's Hall and at Sunday League Concerts at the London Palladium during this time.88 More nationalist sentiment can be found in another early Mackay Brothers advertisement for an Afrikaans record of a c. 1910 London recording of the Treurmarsch, a funeral march for Paul Kruger to the music of the Transvaalsche Volkslied by the British group The Black Diamonds89 (although their name does not appear on the advertisement).90 It was priced at two shillings and sixpence.

The SAME has a detailed list of several other pre-1912 recordings, including Ada Forrest's early recording of Hondt het Fort (which is actually misspelt, it should be Houdt het Fort), c. 1907.91 She also recorded "Die stor van Bethlehem" (again misspelt) in 1908. The majority of Forrest's recordings were in English and it is doubtful that she had any overt political leanings. Between 1909 and 1913, she performed regularly at the Promenade concerts held at Queen's Hall, although never in Afrikaans.92 Another singer who did, however, perform and record in Afrikaans was Floriel Florean. She recorded Hul sal dit tog nie Kry nie/ Overtuiging, Ou Tante Koos/ Grietjie, and Mamma, k wil n man hê/ Toe sê de Magistraat,93all dated c. 1911.94 Florean was known in London as the "Taal singer", and performed recitals of exclusively Afrikaans folk songs at the prestigious Bechstein Hall in 1913. Notably, she donated half of her earnings to the suffragettes.95

The Peerless Orkes' Vat jou Goed en Trek Ferreira/ Tikkiedraai -Selections of Popular Afrikander Songs and Airs of 1909-1910 were also among the earliest Afrikaans music recordings.96 All these recordings feature a mixture of Afrikaner national anthems, hymns and spirituals, Afrikaans dialogues and popular, light songs. Because they were recorded overseas, the accompanists were seldom South African, let alone Afrikaners. In South Africa, informal popular music performances, especially dance music, were often carried out by coloured musicians,97 but were not recorded. Furthermore, if one considers the sensation the first gramophone records caused in South Africa, with people flocking to public record concerts held nationwide,98 it had to be a profound experience for Afrikaners. Not only did this new technology amaze listeners, but to be able to listen to Afrikaans music - like the anthem of the old Transvaal Republic - sung by sympathetic European singers, or the Springboks singing in Afrikaans while the trauma of the war was still raw, must have stirred up strong emotions. Pretorius mentions that Boer commandos were occasionally entertained in the field by music boxes looted from the British or from abandoned farmsteads (in one instance they came across a music box that only played three German songs),99 although it is unlikely that they ever listened to Africana records during the war.

Recordings in South Africa, 1912

The number of Afrikaans recordings increased exponentially from 1912, when the UK-based Gramophone Company sent a mobile recording unit, with recording engineer George Walter Dillnutt, to South Africa to make local recordings. These were probably the first in Africa, and were released under the subsidiary label Zonophone.100 Over 260 recordings were made in Johannesburg and Cape Town during March and April that year and the SAME lists at least 126 Afrikaans tracks that were released as albums.101 Quite a number of these were of religious songs. The Het Moeder Kerk Koor from Cape Town, conducted by C. Denholm Walker, recorded 28 spirituals mostly directly translated from English, with a smattering of psalms and hymns.102

Among the others were recordings of Afrikaans stories, notably by poet Melt J. Brink's own works, like Mijn Land, mijn Volk, en Taal, and Die Vrome meid, Deel 1/ Deel 2, as well as Afrikaan Talking.103 Brink was well-known local poet, as well as a prolific playwright, known for his humorous pieces.104 Singer P.J. du Toit recorded N' Dronk Liedjie van n Mozambique en N Jolly Hotnot in Johannesburg in 1912.105 This song has an overtly racial connotation: a '"Mozambique" in such a context is a reference to an imported slave (see also the quote above), and "Hotnot" a derogatory term referring to a coloured person. The comic Willem Versfeld featured prominently and made at least 26 recordings, including the humorous Bantu song Sakobong Songki.106Although the themes varied substantially between "a blend of spoken word, humorous monologues, Afrikaans folk songs and other somewhat bawdy and also racist tunes",107 they bear witness to the Afrikaner's weltanschauung at the time. Also noteworthy is that there are very few recordings of Afrikaner national anthems among these.

From 1 November 1912, Mackay Brothers also advertised these locally recorded Zonophone Double Discs at three shillings and sixpence per 10-inch record and five shillings per 12-inch.108 Two other advertisements - one by Columbia-Rena Records (at a slightly more affordable three shillings) and another by its local representative Polliack's, soon followed in the issue of 15 December 1912.109 All these companies and their local agencies, were involved in the local record industry for a number of years, which makes them very influential during the early part of the Afrikaans record industry. These examples of cultural ephemera are important because they targeted a specific Afrikaner market. The issue of price is germane. At three shillings and sixpence per record, they were relatively expensive. In 1930 an advertisement for Gallo's Singer Afrikaans records shows that they were priced at four shillings and sixpence,110 more than the daily wage of three shillings and six pence for white unskilled labourers during this time.111

On the other hand, the Carnegie Report showed that poor Afrikaners found access to gramophone players: "Immediately they start living in luxury; instead of saving, they buy a number of things they do not need, such as a gramophone or a piano."112 This statement is the only reference to musical activities among poor whites in the 1932 report. Musical instruments and gramophone players were associated with the "improvident carefree life" of poor whites: living lavishly when they had money, and depending on charity when not.113 Along with other social ills like crime, unemployment and a lack of education, to which they were exposed, it indicated a maladjustment to the economic decline of alarmingly high numbers of poor whites. Unfortunately it is impossible to determine exactly how many poor Afrikaners owned gramophone players before the First World War, although the number of Afrikaans recordings and advertisements hints at some demand.

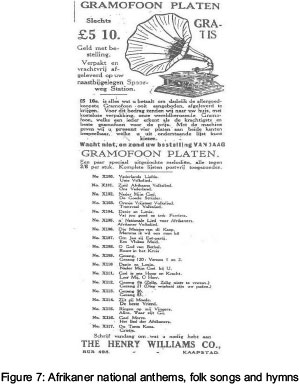

Figure 7 below, a 1916 advertisement for gramophone records (many of which were probably recorded in London before 1912) shows three main themes: nationalism, folk songs and spirituals. Various nationalist anthems were recorded, like Vaderlands Liefde, Unie Volkslied, Zuid-Afrikaanse Volkslied, Oranje-Vrijstaat Volkslied, Transvaal Volkslied, and Afrikaner Volkslied. Popular folk songs were Mamma ik wil Een Man hê, Ou Tante Koos, and Grietjie.114 These recordings were significant since on the one hand, they played on the nostalgia associated with the independence of the old Free State and Transvaal Republics, and on the other appealed to a separate political identity for Afrikaners inside the Union. They also carried extra significance in the wake of the 1914 Rebellion, when many Afrikaners sought independence for the Union from Britain. Furthermore, the prominence of Kruger in early recordings (like the Treurmarsch), signifies his prominence as Afrikaner leader. Apart from nationalism, this much larger sample of recordings (including those of the following decades) contain codes of racial dominance, language aspirations, anti-imperialism and religion - all themes that were later invoked during the 1930s and the rise of a more "virulent"115 form of Afrikaner nationalism.

The development the South African recording industry was interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, when it became too difficult to send the recordings back to England for pressing and then back again to South Africa as the finished product. It only resumed in 1924, when the Edison-Bell Company sent a recording studio to Cape Town, where 50 double-sided albums were recorded using new acoustic technology. Of these recordings, only eleven were in Afrikaans, and were mostly light operatic singers and church choirs.116 The following year saw an increase in the number of local recordings - still mostly in English - with the introduction of electric recording technology. Most of these new recordings were done for the HMV Company.117 The material differed somewhat from the earlier recordings in that national anthems and folk tunes did not feature so prominently.

By this time, of course, the Afrikaner political landscape had changed notably. Hertzog's National Party came to power in 1924 and Afrikaans was recognised as one of the two official languages of the Union in 1925. However, the language issue persisted in many ways while the issue of poor Afrikaners remained paramount. Whereas during the first two decades of the twentieth century, poor white-ism was regarded as the result of inherent weakness, attitudes changed after the Carnegie Commission's report. The social upheaval caused by the Great Depression in the early 1930s, exacerbated by the great drought of 1932-33, were especially hard felt by Afrikaners. Despite these conditions, this era saw a marked increase in the number of Afrikaans music recordings, including vastly popular boeremusiek albums, which underscored clear heterogeneous elements of class and political affinity that fall outside the direct scope of this article.

Conclusion

The complexity of Afrikaans music performance, as well as its diversity, is under-represented in early popular Afrikaans music records. This not only bears some testament to the racial politics intimately involved in the development of the Afrikaans language as well as popular Afrikaans music, but also of the contingent nature of these developments. What does appear to be a salient feature in early Afrikaans gramophone records is the close relationship between one emerging section of white Afrikaans speakers and their claims for nationhood in the early twentieth century._The trauma of the Anglo-Boer War and its immediate aftermath determined the socio-political context of these recordings of which the earliest were sung not by Afrikaners, but by sympathetic singers in continental Europe.

The recordings of various Afrikaner national anthems in London by patriotic Afrikaans singers around the time of Union, and the subsequent advertisements in Die Brandwag, coincided with a rapidly changing cultural landscape. Although few anthems were recorded in South Africa in 1912, the wider range of themes still reflected a growing Afrikaans cultural industry with strong links to Afrikaner nationalism, although the political content of these records should not be overstated. Advertisements for recorded Afrikaner anthems dated to 1916 do suggest some level of nostalgia to a politically independent past. Ultimately, one cannot claim that all pre-WW1 Afrikaans and Africana gramophone records represented an acute self-awareness of a developing linguistic identity and political self-determination, but they were nonetheless part of a growing number of cultural products at a particularly sensitive stage in the development of Afrikaner identities.

1. For example, see E.C. Pienaar, Die Triomf van Afrikaans: Historiese Oorsig van die Wording, Ontwikkeling, Skriftelike Gebruik en Geleidelike Erkenning van ons Taal, (Nasionale Pers, Kaapstad, 1943); [ Links ] M.S. du Buisson, Die Wonder van Afrikaans: Bydraes oor die Ontstaan en Groei van Afrikaans tot Volwaardige Wêreldtaal (Voortrekkerpers, Johannesburg, 1959). [ Links ]

2. P. Roberge, "The Formation of Afrikaans", Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, No. 27, 1993, p 48. [ Links ]

3. D. Constant-Martin, Sounding the Cape: Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa, (African Minds, Somerset West, 2013), pp 54-95. [ Links ]

4. Constant-Martin, Sounding the Cape, p 55.

5. G. Stell, X. Luffin and M. Rakiep, "Religious and Secular Cape Malay Afrikaans Literary Varieties Used by Shaykh Hanif Edwards (1906-1958)", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 163, 2/3, 2007, p 289. [ Links ]

6. F. Ponelis, "The Development of Afrikaans", in R. Dirven, M. Putz and S. Jager (eds), Duisberg Papers on Research in Language and Culture, 18 (Peter Lang, Frankfurt, 1993), p 69. [ Links ]

7. Stell, Luffin and Rakiep, "Religious and Secular Cape Malay Afrikaans Literary Varieties", p 289.

8. J. van Wyk, "Afrikaans Language, Literature and Identity", Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, 77, May 1991, p 85. [ Links ]

9. L. Witz, Apartheid's Festivals: Contesting South Africa's National Pasts (Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2003), p 13. [ Links ]

10. Constant-Martin, Sounding the Cape, pp 69-92.

11. J. Bouws, Solank daar Musiek is: Musiek en Musiekmakers in Suid-Afrika (1652-1982), (Tafelberg, Kaapstad, 1982). [ Links ]

12. W. Froneman, "Pleasure beyond the Call of Duty: Perspectives, Retrospectives and Speculations on Boeremusiek", D.Phil thesis, Stellenbosch University, 2012, pp 49-62. [ Links ]

13. To quote Isabel Hofmeyr in her chapter title "Building a Nation from Words: Afrikaans Language, Literature and Ethnic Identity, 1902-1924", in S. Marks and S. Trapido (eds), The Politics of Race, Class and Nationalism in Twentieth-century South Africa (Longman, Harlow, 1987). [ Links ]

14. J.P. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1 (Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 1986), pp 350-385. [ Links ]

15. R. Bauer, The New Catalogue of Historical Records, 1898-1908/09 (Sidgwick & Jackson, Michigan, 1947). [ Links ]

16. Electronic communication with Alan Kelly, 29 October 2014.

17. The Alan Kelly Matrix Listings, available at http://www.normanfield.com/kelly.htm, accessed 19 June 2014. See also A. **Kelly, "Structure of the Gramophone Company and its Output, HMV and ZONOPHONE, 1898-1954", September 2000, p 3, available at The Truesound Online DiscographyProject,http://www.truesoundtransfers.de/disco.htm, accessed 18 July 2014.

18. Alan Kelly Catalogue, available at http://charm.rhul.ac.uk/index.html, accessed 5 October 2014.

19. Available at http://www.truesoundtransfers.de/disco.htm, accessed 18 July 2014.

20. For example, the author's search of almost 100 000 titles yielded just 15.

21. Available at http://www.flatinternational.org/templatevolume.php?volumeid=280, accessed 12 June 2014.

22. E. Rosenthal, Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa, Fourth edition (Frederick Warne, London, 1967), p 170. [ Links ]

23. Invented by Thomas Edison in 1877.

24. F.W. Gaisberg, Music on Record (Robert Hale, London, 1948). [ Links ]

25. Kelly, "Structure of the Gramophone Company and its Output", p 3.

26. Kelly, "Structure of the Gramophone Company and its Output", p 3.

27. This is as far as can be ascertained by consulting various matrix listings. It is possible that there might be more, since the listings are not complete.

28. J. Bouws, "Nederlandse Komponiste en die Afrikaanse Lied", Die Huisgenoot, 22 November 1946, p 25. [ Links ]

29. R. Trewhela, Song Safari (Limelight Press, Johannesburg, 1980), p 26. [ Links ] See also Bouws, "Nederlandse Komponiste en die Afrikaanse Lied", p 25.

30. Trewhela, Song Safari, p 26.

31. W. Ludemann, "Buren-Marsch: Die Transvaalse Volkslied in Duitse Gewaad", LitNet Akademies, 5, 1, August 2008. [ Links ]

32. Alan Kelly Catalogue, available at http://charm.rhul.ac.uk/index.html, accessed 5 October 2014.

33. Alan Kelly Catalogue, http://charm.rhul.ac.uk/index.html, accessed 5 October 2014.

34. Alan Kelly Catalogue, http://charm.rhul.ac.uk/index.html, accessed 5 October 2014.

35. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 405. See also Truesound Online Discography, available at http://www.truesoundtransfers.de/disco.htm, accessed 18 July 2014.

36. Alan Kelly Catalogue, http://charm.rhul.ac.uk/index.html, accessed 5 October 2014.

37. E. Blom (ed.), Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Volume 11 (Macmillan, London, 1954), p 665.

38. http://www.truesoundtransfers.de/disco.htm, accessed 18 July 2014.

39. Bouws, "Nederlandse Komponiste en die Afrikaanse Lied", p 25.

40. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 350.

41. http://www.truesoundtransfers.de/disco.htm, accessed 18 July 2014.

42. http://www.truesoundtransfers.de/disco.htm, accessed 18 July 2014.

43. Bauer, The New Catalogue of Historical Records, p 425.

44. A. Spoel, Vereenigd-Afrika. Lied en Koraal voor eene Zangstem en Koor met Piano of Orgel Begeleiding. Op. 18 (Van Eck, Gravenhage, 1899). [ Links ]

45. Neerlandia, 25 (Dordrecht, Geuze & Co, 1921), available at http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/nee, accessed 16 July 2014.

46. Van Wyk, "Afrikaans Language, Literature and Identity", p 80.

47. Van Wyk, "Afrikaans Language, Literature and Identity", p 80.

48. Van Wyk, "Afrikaans Language, Literature and Identity", p 80.

49. De Afrikaanse Patriot, 1, 1, 15 January 1876, pp 1-1.

50. S.C.H. Rautenbach, "Die Kerksang as Agtergrond van die Poësie uit die EersteTydperk", Tydskrif vir Volkskunde en Volkstaal, 3, 1946, p 87.

51. Bouws, "Nederlandse Komponiste en die Afrikaanse Lied", p 106.

52. N.H. Theunissen,"Ons Volksliedjies", Die Brandwag, 7 October 1938, p 17.

53. Rautenbach, "Die Kerksang as Agtergrond van die Poësie uit die Eerste Tydperk", pp 85-87.

54. Rautenbach, "Die Kerksang as Agtergrond van die Poësie uit die Eerste Tydperk", pp 86-87. See also Theunissen, "Ons Volksliedjies", p 17.

55. http://www.vetseun.co.za/anarkans/nav/toonsetverwerkkomposeer.htm, accessed 6 August 2014.

56. For further discussion on the link between national anthems and political and military conflict, see Ludemann, "Buren-Marsch", p 58.

57. Alan Kelly Catalogue, http://charm.rhul.ac.uk/index.html, accessed 5 October 2014.

58. University of Stellenbosch (hereafter US) Documentation Centre, J.J. Smith Collection, PV 333.K.G. 14. The letter refers specifically to the gezange recorded by Annie Visser.

59. US Documentation Centre, J.J. Smith Collection, PV 333.K.F.1 (86), (88), (98).

60. J.D. Froneman, "H.F. Verwoerd's Student Years: Cradle of his Political Career and Thought", Koers 65, 3 2000, p 401. [ Links ]

61. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 379. [ Links ]

62. Trewhela, Song Safari, p 35. See also Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 379. [ Links ]

63. A. Pakendorf, "Afrikaans Music History" at http://myfundi.co.za/e/Afrikaansmusic:History, accessed 28 August 2011. See also Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 350.

64. This was the local distributor for HMV and Zonophone and one of the first companies to sell records in South Africa.

65. Die Brandwag, 15 November 1910, p ii.

66. If you have a gramophone player, you no longer have to buy English records if you want to listen to good music. These new records will enable you to listen to the finest songs and the most beautiful hymns of today in one's own language, so close to the heart of the Boer.

67. G, Preller, "Laa't Ons Toch Ernst Wezen", quoted in Hofmeyr, 'Building a Nation from Words", p 104.

68. Hofmeyr, "Building a Nation from Words", p 106.

69. Hofmeyr, "Building a Nation from Words", p 111.

70. Afrikaans Volkslied and Zuid Afrikaans Volkslied.

71. Die Brandwag, 15 November 1910.

72. US Documentation Centre, J.J. Smith Collection, PV 333.Pe.2 (7).

73. Trewhela, Song Safari, p 35.

74. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 357.

75. L. Laubscher and G. Nieman, The Carolin Papers: A Diary of the 1906/07 Springbok Tour, (Rugbyana Publishers, Pretoria, 1990). [ Links ]

76. F. Stegmann, "Baanbreker van die Afrikaanse Lied", Die Huisgenoot, 15 March 1963, p 61.

77. The South African Audio Archive, available at http://www.flatinternational.org/search.php, accessed 20 June 2014.

78. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 383.

79. J.P. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 4 (Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 1986), p 457. [ Links ] See also IzakGrové, "'Making the Dutchman proud of his language...': 'n Honderdjaar van die Afrikaansekunslied", TydskrifvirGeesteswetenskappe, 51, No. 4: December 2011, p. 667

80. F. Stegmann, "Annie Visser het Eerste in Londen Opgetree", Die Burger, 7 September 1961. [ Links ]

81. Stegmann, "Baanbreker van die Afrikaanse Lied", pp 9, 61.

82. Stegmann, "Baanbreker van die Afrikaanse Lied", pp 9, 61. See also Stegmann, "Annie Visser het Eerste in Londen Opgetree"; and Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 4, pp 456-457. [ Links ]

83. De Goede Hoop, July 1903, p 146.

84. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 374. [ Links ]

85. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 380. [ Links ]

86. Hofmeyr, 'Building a Nation from Words", p 109.

87. Malan, (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 376. [ Links ]

88. Malan, (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 3 (Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 1986) pp 353-356. [ Links ] See also http://saoperasingers.homestead.com/Kate_Opperman.html, accessed 28 November 2014.

89. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 350. [ Links ]

90. Die Brandwag,15 June 1912, p. iv.

91. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 370. [ Links ]

92. www.Bbc.co.uk/proms/archive/performers/search/ada-forrest/1, accessed 20 Oct 2014

93. Song titles were often spelt differently in a different release. This was spelt Toe sê di magistraat. See also the variations of spelling of the Transvaal anthem mentioned earlier.

94. Malan (ed), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 374. [ Links ]

95. The British Journal of Nursing, 11 January 1913, p 36.

96. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 377. With regard to these early London recordings, the SAMEs discography provides detailed listings that need not be reproduced here.

97. For a detailed discussion on racial identities in the development of popular Afrikaans music, see Froneman, "Pleasure beyond the Call of Duty", pp 49-76.

98. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 354.

99. F. Pretorius, Life on Commando during the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902 (Cape Town: Human & Rousseau, Cape Town, 1999), p 126. [ Links ]

100. L. Meintjies, Sound of Africa! Making Music Zulu (Duke University Press, London, 2003), p 275. [ Links ] See also http://www.flatinternational.org/template_volume.php?volume_id=280, accessed 12 June 2014.

101. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, pp 356-385. [ Links ]

102. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 375. [ Links ]

103. Malan (ed), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, pp 360-361. [ Links ]

104. US Document Centre, Melt J. Brink Collection, MS 9.

105. Malan (ed), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, p 368. [ Links ]

106. http://www.flatinternational.org/templatevolume.php?volume_id=280, accessed 12 June 2014.

107. http://www.flatinternational.org/templatevolume.php?volume_id=280, accessed 12 June 2014.

108. Die Brandwag, 1 November 1912, p xv. See also Trewhela, Song Safari, p 44.

109. Die Brandwag, 15 December 1912, p xiv and p xcvii.

110. Opskommel, 1992, Vol. 1, p 16. , available at http://www.boeremusiek.org/Afrikaans/Nuus/Opskommel/, accessed 17 September 2012

111. H. Giliomee, The Afrikaners: Biography of a People (Tafelberg, Cape Town, 2003), pp 323-324. [ Links ]

112. J.R. Albertyn, The Poor White Problem in South Africa: Report of the Carnegie Commission, Part 5 (Pro Ecclesia, Stellenbosch, 1932), p 42. [ Links ]

113. Albertyn, The Poor White Problem in South Africa: Part 5, p 42.

114. W. Schultz, Die Ontstaan en Ontwikkeling van Boeremusiek (AVA Systems, Pretoria, 2001), p 183. [ Links ]

115. P. Bonner, P. Delius and D. Posel (eds), Apartheid's Genesis, 1935-1962 (Ravan Press, Johannesburg, 1993), p 1. [ Links ]

116. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, pp 361-385. [ Links ]

117. Malan (ed.), Die Suid-Afrikaanse Musiek Ensiklopedie, Volume 1, pp 361-385. [ Links ]