Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Historia

On-line version ISSN 2309-8392

Print version ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.59 n.2 Durban Nov. 2014

ARTICLES

"Entrenching nostalgia": The historical significance of battlefields for South African tourism

Richard Wyllie

Richard Wyllie currently holds the position of chief researcher in the Department of Historical and Heritage Studies at the University of Pretoria, working on a collaborative project with the National Department of Tourism. His Masters dissertation at the University of Pretoria is in the field of Heritage and Cultural Tourism and focuses on tourism collaboration in transfrontier conservation areas. His interest in the battlefields has stemmed from his honours research report

ABSTRACT

Many famous battles have left legacies and these have often created a sense of nostalgia motivating people to visit associated sites. Battlefields and other sites of "death and decay" have increased as a popular sub-sector of the fast growing heritage and cultural tourism industry. Battlefields, and other sites associated with war, have been studied by scholars from a variety of disciplines. In more recent times, tourism professionals and academics have begun to study battlefields and their associated histories for the purpose of developing and promoting them as tourist attractions. This has resulted in a distinct link between the historical and tourism sectors. In this paper, the Battle of Spioenkop (KwaZulu-Natal) will be discussed as an example of how history and a battle site in particular can contribute to the development of tourism.

Keywords: Heritage; tourism; battlefield tourism; Battle of Spioenkop; Battlefields Route; "dark tourism"; "thanatourism".

OPSOMMING

Menige bekende veldslae het nalatenskappe gelaat wat dikwels 'n gevoel van nostalgie skep en mense motiveer om verwante terreine te besoek. Slagvelde en ander plekke van "dood en verval" het 'n toenemende gewilde sub-sektor van die vining-groeiende erfenis- en kulturele toerisme-industrie geword. Slagvelde en ander plekke wat verband hou met oorlog, word deur geleerdes van 'n verskeidenheid dissiplines bestudeer. Toerisme-spesialiste en akademici het onlangs begin om slagvelde en die gepaardgaande geskiedenis te bestudeer vir die ontwikkeling en bevordering van die slagvelde of terreine as toeriste-aantreklikhede. Dit het gelei tot 'n tasbare verband tussen die historiese en toerisme-sektore. In hierdie studie sal die Slag van Spioenkop (KwaZulu-Natal) bespreek word as 'n voorbeeld van hoe die geskiedenis, en 'n veldslag-terrein in die besonder, kan bydra tot die ontwikkeling van toerisme.

Sleutelwoorde: Erfenis; toerisme; slagveld-toerisme; Slag van Spioenkop; slagveldroete; "dark tourism"; "thanatourism".

Understanding history and heritage

The word history is derived from the Greek word "historia", which means "to know".1 It is generally accepted as a reference to the past and is regarded as a reconstruction or an account of that past.2 Munslow has simply defined history as: "That narrative representation intended to provide a coherent and ordered body of explanations and meanings about the past produced by the historian".3 Deacon also defines history as the study of what has happened in the past, based on the interpretation of sources.4 Although this source material is often fragmented, imperfect, provisional and sometimes contradictory a narrative is constructed in order to enhance the understanding on how or why an event occurred or why a historical figure or people may be considered as significant.5 Historians may also use the physical remains of communities, such as ruins of old buildings, pottery shards and weapons, to reconstruct the past. Places and landscapes may also be considered as historical sources and include mountains, sacred areas and historical buildings. These localities are important as they may contain pieces of evidence that are related to significant events or people of the past.6

Carr believes that history is a continuous process of interaction between a historian and facts, a process which creates a platform for a continuous discussion between the present and the past.7 While it is generally held that, "facts speak for themselves", Carr states that in the study of history, "facts will only speak when they are called upon by the historian".8 In this regard, Jane Carruthers and Sue Krige suggest that history is, "two-sided" as it is produced by historians and "received" by other historians and the public - meaning that history involves a constant interaction between the author and the audience.9

Another important concept in the context of this paper is the term "heritage". The word is derived from two French words - eritage and heriter, which both mean to "inherit".10 It is therefore something that has come to belong to someone by or through a birthright either as a lot or as a portion.11 It is however one of the most contentious and contested concepts and has often proven to be quite problematic. Within these debates, heritage is often seen as a "re-creation of the past" or an "act of remembrance" through the giving of a name, the erection of a monument, or by the way objects are displayed in a museum.12 In other words, heritage can be viewed as "what is created in the present in order to remember the past".13

The word "heritage" was used for the first time in South African legislation in The National Heritage Resources Act No. 25 of 1999.14 It declared that heritage contains both an important national and political function as well as a significant role in defining South Africa's cultural identity and contributing to nation building.15

Heritage is then further divided into two categories: tangible and intangible forms.16 Firstly, tangible heritage is the type that presents itself in a material or physical form, such as archaeology; art; architecture; and physical landscapes, while intangible heritage is a form which cannot be seen and is presented in a more spiritual and creative form. For example, oral traditions cannot be seen or touched but they are still important elements of heritage.17

Heritage is said to have two different meanings: An individual person's heritage and a country's national heritage. An individual's heritage is made up of the practices and traditions that are passed on from parents to children and it is also about what has been passed on from families, communities and places where people have been raised. A country's national heritage includes the natural heritage (the environment and its natural resources) and the cultural heritage (formed by those things or expressions that show the creativity of people).18 Both these forms of heritage are significant in the tourism sector.

Since the late nineteenth century, the second form of heritage has been used as a tool to promote a sense of patriotism and national identity for its citizens. In a global sense, historians have played a crucial role in helping to recover the pasts of cultures that have been both marginalised and neglected.19 For example, in former colonial countries such as South Africa, many cultures have been marginalised in the past and historians have now been tasked with bringing these histories "back to life" and include the heritage of these forgotten cultures. Many cultural groups now rely on historians as well as heritage officers to help them with preserving and honouring their cultural heritage.20

In considering the relationship between history and heritage, Ciraj Rassool points out that heritage, in its many manifestations, is considered to be "public history" and it is also a form of packaged history that can be presented to tourists and the general public in the form of monuments, museums and other heritage sites.21 Similarly, Glassberg defines public history, as: "Those forms of historical representation which are produced outside the academy, either directly addressing a large general audience, or for public, often governmental, purposes".22

Thus, in differentiating between history and heritage, the primary concern of history is how certain events and people of the past are interpreted and narrated through a constant dialogue between an author and an audience, whereas heritage focuses on the audience, or the recipient of the history, rather than the author.23 Some historians are cautious about heritage as it often leads to the commodification or subversion of history, that is the packaging and selling of history to an audience that is not necessarily apt for receiving it.24 Therefore while the presentation of heritage has the potential of promoting economic development, it is also believed to sometimes compromise history.25 Furthermore, according to Carruthers:

Many heritages can be problematic, posing distinct theoretical challenges to the discipline of history and whether heritage is always valid should be questioned as well as, from the standpoint of an academic historian, should 'heritage be treated as primary sources or raw data and subjected to evidential scrutiny?26

Heritage has close ties with the notions of "memory" and it can often be associated with certain cultural groups or specific individuals. Memory is not only regarded as an individual and cognitive act of remembering, but it is also a social activity of reconstructing the past.27 Memory, in both particular and universal forms, may change according to the way that we think or perceive of ourselves, of the past and how we engage with the past and thus develop narratives.28 Memory is also considered to be linked with a place or to a person and this in turn influences the experiences of tourists as to how and why they have chosen to remember the places, people and cultures that they visit.29 Another concept that is often associated with heritage and tourism is "nostalgia". This is defined as, "a pleasure and sadness that is caused by remembering something from the past and wishing that you could experience it again".30

The presentation and interpretation of South Africa's past and heritage has developed along very similar lines to its history, which is oppressive and has neglected large sectors of society.31 Until the 1980s, very few museums or monuments in South Africa displayed stories, objects or memories of the marginalised people of the country; most of these lauded the white population or a white version of the past.32 Since then, heritage practitioners and historians have identified sites of "neglected" peoples and events and have written and/or included them as part of South Africa's national heritage.33 An example of this is the Battle of Blood River site in the northern region of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, which has two museums - one representing Zulu culture (the Ncome Museum) and the other representing Afrikaans culture (the Voortrekker Museum).34 Here heritage is presented in a manner that will allow for "both sides of the story".

Heritage and cultural tourism, thanatourism and battlefield tourism

The notion of war is a uniquely human phenomenon which is frequently lacking in logic but is always characterised by paradox. In other words, war is something that it is seemingly absurd and contradictory.35 Within the many paradoxes of war, there arises the human need to visit battlefields and some of the motivations to do so may include the need to remember comrades who were killed in battle; to pay tribute to loved ones who have died in battle; to ponder the feats and acts of heroism of those who were mainly unknown to the general public; and to rejoice in victory - or even to ponder over defeat. Yet whatever the reason or motivation for visiting a battlefield, the notion has certainly emerged as a growing sub-sector of the tourism industry, one which is often tinged with nostalgia.36

Some of the most significant tourist sites in the world, especially in South Africa, are ones that have come from times of war and conflict.37 Wartime events, sites, and landscapes have become important attractions which act as major draw cards for a wide scope of visitors.38 By visiting these heritage sites, tourists are constantly adding to the fastest growing sector of today's tourism industry, which is known as Heritage and Cultural Tourism.39 This was defined in 2013 by the South African National Department of Tourism as:

A form of tourism that allows the tourist to experience different ways of life, to discover new foods and customs and to visit cultural sites which have become leading motivations for travel, and ... [provides] a crucial source of revenue and job creation, particularly for developing countries.40

As indicated, both memory and nostalgia are heavily linked with tourism and war heritage sites, and in particular sites which may hold emotional memories, such as battlefields. For example, battlefields provide an ideal platform for the study of how memory and nostalgia are linked with heritage.41 The urge to visit a battlefield or an associated site falls under the scope of the international tourism sector known as "thanatourism" or "dark tourism".42 Anthony Seaton has simply defined thanatourism as "travel to a location wholly, or partially, motivated by the desire for actual or symbolic encounters with death".43

Paul Williams has emphasised the growing nature of thanatourism by showing that more memorials and monuments have been erected in the first decade of this century than the whole of the twentieth century combined.44 In addition to this, Richard Sharpley has discovered that this trend is very much on the rise.45 There is also a specific type of thanatourism which has come to be known as "warfare tourism" or "war tourism", and it involves specific travel to war memorials, monuments and museums, as well as war experiences such as battle re-enactments at a particular site.46 For example, in the KwaZulu-Natal region of South Africa, members of the Dundee Diehards come together to re-enact the Battles of Isandlwana and Rorke's Drift on 22 January each year at the actual battle sites.47 War tourism has a significant niche market and it has increased in prominence in both the tourism industry as well as academic literature over the last decade.48

War tourism, also includes another particular form of tourism which is usually referred to as battlefield tourism, which itself falls under the umbrella of thanatourism. According to Prideaux, visiting specific sites of battle is a growing sub-sector in the tourism industry today.49 There have been numerous studies of battlefield tourism in specific contexts.50 Studies on the First and Second World Wars include those by Walter who investigates the desire to make pilgrimages to grave sites;51 and the work of Baldwin and Sharpley who have done research on the general appeal of battlefields from the World Wars and why they are significant for tourism and heritage studies.52 Other avenues of research include the battlefields of Gallipoli to Australia and New Zealand and investigations of Vietnam battlefield tours and sites.53 The extent of growth and popularity of battlefield tourism is clearly evident in many global regions today. Locally, the provincial tourism authority for KwaZulu-Natal (Tourism KZN) has bought into this growing trend by establishing a recognised tourism route, known as the Battlefields Route.54 Established in 1999, it builds on existing battlefield tourism offers tourists the opportunity to travel distances of more than 400 kilometres to over 36 different sites, either on their own or with a tourist guide.55

These multiple types of tourism have created an almost umbrella-type format which is illustrated in Figure 1 below. This figure, which has been adapted from R. Dunkley et al,56 shows the types of tourism that fall under the broader sector of Heritage and Cultural Tourism.

The battlefield tour to the site of the Battle of Waterloo of 1815 is one of the earliest known examples of warfare tourism. Apparently, the desire of the tourists to visit this battlefield was so intense that they made their way to the site while the battle was still raging.57 Another example which indicates the remarkable level of the interest in battlefields is that in 1915 the Thomas Cook travel agency received so many requests for tours to the World War battlefields that they had to publish a public notice in The Times warning that there would be no conducted tours to the battlefields until the hostilities had ceased and it was safe for people to enter the landscape.58 These tourists were labelled "trench tourists" by scholars such as Sherman who has identified the frustration of the troops and how they did not appreciate visitors, such as journalists, politicians and civilians, to the respective active battlefield.59 The First World War (1914-1918) has left an indelible impact on the imagination of many people, especially those living in Europe.60 The slaughter of millions of young men caused by industrial trench warfare left a lasting legacy on "a community of the bereaved" in Europe as well as the colonial world.61 These communities became one of the first groups of battlefield tourists who by travelling to mourn their loved ones were essentially motivated to tour by factors such as memory and tribute. The Second World War (1939-1945) also proved to be another key event which resulted in battlefield tourism. Tourists wanted to view actual battlefields where monuments and memorials were erected as well as places of other atrocities such as Auschwitz and Hiroshima.62

Wars and their associated battles undoubtedly have a significant place in history and in the national consciousness of many countries. Some battles have a great significance in the culture of a nation and are expressed through the art, literature and music of that nation for the purpose of creating a sense of national identity or nation building.63 Battlefields are sites which may contain physical remains of a battle or even archaeological material which can possibly enhance the understanding of past events. Many battlefields are also the last resting place of massacred soldiers and even if these sites contain no national significance, they are still significant for the families of the fallen.64 Battlefields hold significance for a number of reasons: they may play a part in enhancing a certain sense of place; they establish a local distinctiveness and culture; they enable the understanding and enjoyment of the past; and they create a platform for economic growth through the development of tourism.65 They are also seen as rich resources for education and for fields such as genealogy. Unlike many other historical phenomena, they are perfect places for interpretation as well as recreation because they allow visitors a first-hand experience of the actual location of dramatic events.66 Battlefields afford tourists the opportunity to reflect on the past and to ponder the impact that the battles have had on the generations that followed; the legacy they have left behind and how they have shaped the world as it is today.67

Battlefield tourism gained popularity inn South Africa in the late 1980s, especially in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. An example of this is the late David Rattray who established and operated the Fugitives' Drift Lodge at Rorke's Drift. Rattray is considered one of the pioneers of battlefield tourism in KwaZulu-Natal. As a child he gained extensive knowledge about the conflicts between the Zulu and the British troops in South Africa from his father and remained a keen amateur historian. He was often found interviewing local Zulu people to hear their accounts of the conflicts in the area and on occasion made contact with those whose ancestors had fought in these wars. He offered many tours of the historic battle sites of Isandlwana and Rorke's Drift, which have been estimated to have been attended by more than 60 000 local and international tourists.68 His son and family continue to run this lucrative enterprise.

In order to assess the factors that contribute to the significance of a battlefield, the Historical Policy of Scotland provides some important information. This policy document was drawn up by an organisation known as Historic Scotland, which is an executive agency that of the British government and is responsible for the conservation and protection of the nation's historical and heritage environment. The policy states that a battlefield site is of national importance if it makes a contribution to the understanding of the history and archaeology of Scotland. It therefore has a significant place in creating a national identity.69 The policy document has divided the factors of significance into three categories, namely, an association with historical events or figures of national significance; the discovery of significant physical remains and/or archaeological remains; and an awareness of the battlefield landscape.70

According to this policy, a battlefield may firstly be significant due to its association with historical events or figures who are of national significance. This relates to the contribution that it makes to the understanding of historical development, including the military history of a country or a region within that country. A selection of key considerations will also be made which will focus on whether there were any significant military innovations or occurrences during battle.71 In addition to this, the battle will also be analysed to determine if there is any association with an important historical figure.

In keeping with the trends of history and heritage, a battlefield may also be considered significant if it contains crucial physical remains or archaeological material, that is, "traces of the past".72 The surviving physical remains on or within the region of the battlefield, as well as any archaeological material, are seen as specific qualities of the battlefield and are important sources for both historians and heritage officials. Archaeological material has the potential to increase the credibility of documentary records and it may provide vital information about events, weaponry and the participants which cannot be found from any other sources.73 The physical features that are left behind after a battle include the following: natural elements (hills and ravines); constructed elements (walls, buildings and forts); elements caused by the battle itself (graves and artefacts such as bullets and personal items); and other archaeological deposits such as the remains of camps and entrenchments.74 The surviving historical documentation and map evidence relating to specific battles, or even the war itself, are of crucial importance as they may enhance the overall understanding of the events and occurrences during the period of conflict.75

The final determining factor for the significance of a battlefield, according to the Scottish policy, is the actual battlefield landscape. Wars and battles are seldom fought in small or restricted areas and they were events that took place across wide, extended landscapes with no geographic or political boundaries hindering their cause.76 The study of these landscapes provides important platforms for understanding the military tactics which were deployed during these battles, as well as other strategic planning measures such as the vantage points and lines of sight that were used during the battle.77 The battlefield landscape is comprised of the areas where the troops were initially deployed and where they engaged in conflict with the enemy, as well as the wider areas where other significant events occurred, such as the movement of reinforcements or the path taken during the retreat. It also includes any secondary skirmishes; associated earthworks (trenches); camps; burial sites; lines of advance or retreat; and additional elements such as memorials that may be added to the actual site of battle. The association with the landscape of a battlefield may contribute fundamentally to creating a "sense of place" even when there is no available physical evidence or when the initial character of the landscape has been affected by any post-battle transformations - such as the development of human settlements.78

The significance of battlefields, for both history and heritage, is further amplified by the presence of tourist guides - who are essentially at the "coal face" of the tourism industry. The battlefield landscape is one that requires much interpretation as well as an added sense of imagination in order for the audience to understand the hidden narratives.79 In the case of a historian, it is also the role and responsibility of a tourist guide to interpret the landscape and provide a narrative that will assist the tourists (the audience) to understand the hidden meanings of the site as well as create a platform for discussion and debate. The role of a tourist guide is therefore one that is multidimensional and includes acting as the group leader; an entertainer; and information-giver. The tourist guide is also seen as the promoter of group interaction.80 Jennifer Iles believes that visits to battle sites should entail more than just simply driving to a site so that it can be photographed. Rather, tourist guides should offer their clients an insightful experience and must be able to help them to construct a historical, empathetic and imaginative connection with the landscape.81 In most cases, tourist guides are the people with whom tourists make initial contact with and they should therefore encourage social engagement and support group dynamics right from the start of the tour.82

Battlefield tourist guides and their tour groups have another unique characteristic, and even though this aspect is sometimes found in other tour groups, the context of battlefield tourism creates a very specific dimension of solidarity and "closeness" when a tour group visits a battlefield and other related sites.83 In addition to this, a sense of camaraderie should be encouraged by initiating debates even while the group is relaxing, eating and drinking. This camaraderie and togetherness is closely related to the relationship between the "soldiers" (the tourists) and their "commanding officers" (the tourist guides). This is what creates the unique character which is not often found in other tourist situations.84

In his well-known discussion of the "tourist gaze", John Urry believes that the tourists of the modern day has the need to be an educated traveller and often demands a great deal of information, such as maps and reading material, even before the tour has begun.85 Therefore most battlefield tours supply their clients with a wide range of material such as readings from selected texts; presentations; and sound recordings before and during the tour. This educative material may also include visits to related sites, memorials, monuments and museums.86 By doing this, the guides give themselves enough scope to engage the imagination of the tourists though the explanation and dramatisation of the events that took place in the battlefield landscape.87

The site of a battle is often limited in its ability to narrate its own story and without any significant monuments or memorials the significance of a site can often be overlooked. Therefore the tourist guide is responsible for showing the visitors more than what may have otherwise been perceived in order for them to experience the deeper meaning of the site.88 The guides also try to encourage the tourists to look beyond the actual landscape in order to see and relate to its topography and surrounding areas in a different light - that being an imagination of what this site and its surrounds may have looked like in the past.89

A tourist guide is thus responsible for interpreting a source from the past for a particular audience and they then encourage discussion and debate on this interpretation, which reveals some similarities to a historian.90 Many battlefield tourist guides are often military historians or ex-military officers who have since found an interest in the history of battles.91 Battlefield tour groups are not made up of a homogenous audience - in other words these groups may vary greatly in terms of education levels; age; reason for travel; and the expectations of these tours.92 The audience, in keeping with the shared ideas of history and tourism, are often unable to understand the site in the same way as the guides themselves and should be allowed to interpret the information in their own way with the assistance of the narrative presented by the guide.93

The Battle of Spioenkop

The origins of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 (also known as the South African War)94 remain a much debated issue. Some two decades ago, Albert Grundlingh reflected on this in the following way:

No comprehensive synthesis has yet appeared which systematically analyses the frequent divergent interpretations of the causes of the war and advances the relative importance of the interwoven factors in a way which demonstrates the niceties and the nuances of the situation.95

He adds that it is important to order the events of the war within the context of the underlying structural capitalist system.96 Upon doing this, it is only then that one can move towards the interpretation of all of the complex events which have led to one of the most destructive wars of our history, one which included the renowned Battle of Spioenkop, which will be used here as a case study.

The forces of Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR) and Orange Free State Republic (OFSR) had already advanced into Natal at the outbreak of the war (October 1899) to attack the British forces that had assumed control of the region.97 The British had established themselves in the towns of Ladysmith and Dundee (29 October 1899)98 in the northern regions of Natal. A number of engagements had already taken place between the British and the Boers before this time, such as the battles at Talana/Dundee (20 October 1899) and Elandslaagte (21 October 1899).99 These battles were crucial in terms of the Boers' movement towards Ladysmith because they were then able to besiege the town and in doing so, trap a large concentration of British forces and gain a rapid upper hand in Natal.100

Once they had control of the town of Ladysmith, the Boers decided to relocate themselves to the southern regions of Natal. In the meantime, the British had begun to ship troops into the country through the port of Durban (January, 1900).101 These forces were deployed as reinforcements and their first task was to relieve the besieged town of Ladysmith which was populated by 13 000 British soldiers and 7 000 pro-British civilians.102 The main focus of the war then shifted to the region of the Thukela River in January 1900,103 as the Boers began to reinforce the region in an attempt to prevent the British from moving through the area to relieve Ladysmith.104 The Boer force, under command of General Louis Botha, consisted of 4 500 men, while the British force, under the command of General Sir Redvers Buller, comprised 20 000 men and 44 heavy artillery guns.105 After suffering a heavy defeat at the Battle of Colenso on 15 December 1899, the British were then driven back and were forced to focus their attempts elsewhere.106 Buller then decided to move towards the upper regions of the Thukela River and on 23 January 1990, the Boer and British engaged in one of the most futile and bloodiest battles in military history - the Battle of Spioenkop.107

Thomas Pakenham heads his chapter on the Battle of Spioenkop "Acre of Massacre",108 and heralds it as one of the bloodiest and most futile battles in history. The following quote, from Deneys Reitz, encapsulates this: "There must have been six hundred dead men on this strip of earth, and there cannot have been many battlefields where there was such an accumulation of horrors within so small a compass".109

During the attempts to relieve the British occupied town of Ladysmith, Buller was then joined by Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Warren who brought with him a force of 15,000 men.110 They were ordered to cross the Thukela River to outflank the Boer's defensive line, yet this proved to be a failure because the Boers managed to prevent any penetration of their defence at iNtabamnyama.111 The two Generals, Buller and Warren, then collectively decided to capture Spioenkop, the summit of which was the highest point on the defence line of the Boers. By capturing this hill, the British believed they would then be able to dominate all of the Boer's defensive positions.112 The attack was scheduled for 22 January 1900, but it was later postponed to 23 January 1900 due to a disagreement between the two British generals.113

After much debate, the task of leading the British troops up to the summit was assigned to Major General Sir Edward Woodgate.114 At approximately 03h00 on 23 January 1900, Woodgate led approximately 1 700 men up to the summit from Warren's headquarters which were situated adjacent to Spioenkop at Three Tree Hill.115 At this point of the battle it is important to point out three significant factors that would essentially play a decisive role. First, the men were a light infantry and no heavy artillery guns were taken despite their availability.116 Second, the men were not ordered to carry any sandbags with them in order to reinforce the summit.117 And finally, the section of water carriers were all absent during the ascent of the summit, thus indicating an assumed presumption by the British generals that the battle would be short-lived.118

One of the other British commanding officers, Colonel Thorneycroft, led his troops up to the summit in the most terrible conditions. The men climbed up a very rocky summit with dense vegetation, and to make matters worse, the entire hill was enveloped in thick fog.119 The British forces reached the summit at approximately 04h00 and upon doing so they surprised a small group of Boers from the Vryheid Commando, who promptly fled down the hill to the Boer headquarters to inform Botha of the arrival of the British troops.120 There was pandemonium in the Boer laagers but Botha calmed his troops down and rallied them in preparation for battle.121 The British meanwhile had begun to dig trenches on the summit which was still under a blanket of thick fog and once it started to lift, they then realised their mistake. The trenches had been built in the centre of the summit rather than a more favourable and strategic position on the forward slopes.122 Soon after realising this, the troops began to build forward pickets in an attempt to entrench the forward slopes, but they ran into an even bigger dilemma because the forward slopes had an extremely hard layer of underlying rocks which hindered the creation of trenches.123

From about 07h30, the Boers had already begun to inflict fatalities on the British with highly accurate rifle and artillery fire, while the British could only defend themselves with rifle fire. After several heroic attempts by the British, they were forced back into their trenches by mid-morning.124 During the early stages of battle, Woodgate was wounded and his command was handed over to Colonel Bloomfield, who also fell wounded shortly afterwards.125 This was another crucial factor in the final outcome of this battle because the loss of two commanding officers caused much confusion among the British officers on the summit. Each was unaware that another had taken over command of the attack and the soldiers were given a number of conflicting orders.126

By midday, the casualties among both the Boer and the British forces had begun to increase rapidly. At one point, 180 British soldiers could not cope with the heat and the overall conditions and they surrendered themselves or were taken prisoner by the Boers.127 Despite the arrival of a further 4 000 British reinforcements, Thorneycroft realised that they would still not be able to hold out against the Boer assault from all flanks and so decided to withdraw from the battle.128 He was unaware that the Boers had actually begun to retreat down the summit before the British retreat had begun.129 By 02h00 on 24 January 1900, both sides had successfully withdrawn themselves from the battlefield.130

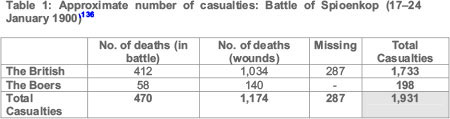

The Boers had been the first to return to the summit later that morning and the scouting party soon discovered that the British had already left the summit.131 They also discovered the horrific scene of death and disaster.132 Soon after this, the Boers allowed the British burial parties to return to the summit to bury the dead, a task that would last for three whole days.133 The majority of the British corpses were buried in the two trenches as well as a number of isolated graves, which are all still visible on the summit today.134 Other British soldiers who had died in battle were buried at Clydesdale Farm and those who died from wounds sustained during the battle were buried at Spearman's Farm.135 The number of casualties has never quite been calculated, but Table 1 outlines the figures which are held to be as accurate as possible:

History, the battle and tourism

The Battle of Spioenkop was significant in South Africa's past for a number of reasons, not only from a historical perspective, but also from a tourism perspective. The battle has been labelled by many historians and tourism stakeholders as one the most famous battles ever fought on South African soil and is probably the most famous battle of the Anglo-Boer War.137 The Historical Policy of Scotland is ideally suited for use as a tool to evaluate not only the historical, but also the touristic significance of this battle. The section below will consider the Battle of Spioenkop under the three categories outlined in the policy document, but it will also go beyond this to consider other links between history, the battle and tourism.

The first category of significance identified in the Scottish policy document refers to the association with an important historical event or historical figures. The historical and touristic significance of this battle is obvious. The pivotal role it played in the Anglo-Boer War, the extensive loss of life, and the almost futile nature of its termination all contribute to the hype surrounding the event. Besides this, another significant factor of this battle, which is both historical and has immense touristic draw-card potential, is the fact that in its aftermath three very significant individuals were present on the summit.

Once the battle had ended, the Boer commandos came up onto the summit and they were joined by British generals who were accompanied by the Indian stretcher bearers. First of all, General Louis Botha, who would later go on to become the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa in 1910, arrived to survey the massacre and to pay tribute to his men.138 Then a 23-year-old war correspondent by the name of Winston Churchill, who later became the prime minister of Britain, was also on the summit.139 Finally, a young Indian man known as Mahatma Gandhi, who was a volunteer for the ambulance corps and later went on to lead India to independence, was also present the summit to bury the dead.140 These three men were all at the summit at the same time and were all in the vicinity of the battle while it was being fought. The convergence of these three historically significant men on Spioenkop adds to its profile as a historically significant place - giving the tourist guide much to speculate about.

In addition to these prominent individuals, there were a number of other military personnel who claimed Spioenkop as their "stomping ground" and played a crucial role in the events of the battle. The British commanding officers all have a national significance in both South Africa and Great Britain and they include Buller, Warren, Woodgate, Thorneycroft and Bloomfield. These men have can also be seen as key historical figures who were closely associated with the Battle of Spioenkop.

Another factor relating to the scene of the battle lies in the context of English football. Liverpool Football Club has a stand in their Anfield Stadium known as the "Kop" and it has become one of the most famous arenas in world football. Not many South African's know this but the name "Kop" is derived from the name Spioenkop - British soldiers from the southern Lancashire Regiment, who suffered a high number of casualties, were heavily involved in the battle on the summit. Therefore the football club has since named a stand to honour the fallen heroes of Spioenkop.141 Once again, the battle's significance is amplified, according to the dictates of the Scottish Historical Policy, because these soldiers are given important historical status as being associated with the battle and are thus commemorated in the stadium. In other words, in addition to prominent historical figures associated with the battle, there are also many ordinary men, in excess of 1 000 of them, who died and hence became heroes in the eyes of society at large and particularly to the descendants of these men on both sides. This in itself is another tourism dimension.

The Scottish policy document points to a second category of interest, that the physical or archaeological remains from a battlefield may determine its significance and this is also of relevance to the Battle of Spioenkop. There are many grave sites which contain physical remains or archaeological material found on top of the summit. For example, in the mass grave built from the original trenches, 200 British soldiers who were killed during battle were buried and the gravesite has become one of the most popular attractions for tourists. Secondly, the isolated graves found scattered on top of the summit are those of important figures, such as Woodgate. Therefore an overlap between the first category (historical figures) and the second ("ordinary" heroes) is evident. A number of other physical remains can also be found on two farms which in the vicinity of Spioenkop. Many of the remains from the original graves at the battle site have since been exhumed and have been re-buried at the Burgher Memorial in Ladysmith.142 In addition, archaeological material has since been removed from the summit and been placed in museums such as the Ladysmith Siege Museum.143

The third and final category, which looks at the battlefield landscape, is also well represented at Spioenkop. For example, the location of Warren's headquarters, found at Three Tree Hill, is significant in terms of its association with the battlefield landscape. Once again, an overlap of categories identified in the Scottish policy document is evident because Warren is also seen as an important figure involved in this battle. In addition to this, there are a number of other sites or features that are associated with the battle and these include: the Thukela River; Botha's headquarters on a "koppie" north of the summit; key military positions such as Conical Hill and Aloe Knoll; the Clydesdale and Spearman farms; the towns of Ladysmith, Talana/Dundee and Colenso; and many other associated memorials, monuments or museums which commemorate the battle. Another important landscape feature is the summit itself. The summit is the highest point in the area which allows those upon it to see an extensive view of the landscape.

Furthermore, it is significant that the geological structure of the hill is still the same today as when the battle took place. This allows visitors to experience its hard, underlying surface as well as the vegetation and topography of the summit. The conditions under which the battle took place are also relevant for tourism, as well as for gaining an understanding of the landscape from a historical perspective. The most nostalgic thana-tourists will often want to "experience" the battlefield under similar conditions, or to stand in the same spot and imagine the conditions, such as the blanket of fog, as they were that fateful day in January 1900. They wish to experience the actual aftermath of the battle and to stand in the same place which was once a "scene of death and disaster".144 The following quote from the travel section of Independent Newspapers Online in 2001, outlines the sought-after tourism experience:

We climbed Spioenkop as the sun dipped behind the distant Drakensberg. The last rays picked out the memorials, a cold wind and the mournful howl of jackals sent shivers down the spine. But it was more than that; it was the ghosts that seem to haunt the famous battlefield.145

In terms of its significance for tourism, the Spioenkop battlefield is one of the most popular sites on the KwaZulu-Natal battlefields route.146 The site can be found in the northern regions of the Drakensberg in the vicinity of both Ladysmith and Winterton. It is surrounded by other important tourist attractions such as Spioenkop Dam and there are a number of accommodation establishments nearby.147 The infrastructure and employment opportunities that have been developed to complement the battle site are indicative of the significance of the site from the perspective of tourism.148 In 2012, the KZN Tourism authorities established that 26% of all tourism arrivals to the province were interested in heritage, historical and cultural tourism sites. In addition to this, 3.3% of all international arrivals have visited the battlefields region.149

Today, the summit has a number of memorials and monuments which act as important draw cards for tourism. The two mass graves on the summit are the most pronounced and have become the most popular attractions. The graves which are in a cross-bow shape and are approximately 400 metres in length hold the remains of 243 British soldiers who were killed in these trenches during the battle.150 There are 15 isolated, marked graves on the summit which have the remains of Boer soldiers that were killed in action.151 One of these is the grave of an "unknown soldier" who was the first Boer to be killed during the battle - he was unfortunate enough to awake just as the British reached the positions of the sleeping Boers and he was stabbed with a bayonet as the British charged up to the summit.152 The 3rd King's Royal Rifle Corps are commemorated by a monument which is found on a saddle between the Twin Peaks.153 There is also a military cemetery at Mount Alice Farm, formerly known as Spearman's Farm in 1900.154

Another memorial (a white iron cross) was found at Mount Alice and this has been used to mark the spot of where General Buller established his headquarters during battle.155

The summit also contains memorials or monuments which act as markers for significant events in the battle. For example, the approximate location of where Woodgate fell wounded in the thick of the fighting is marked by a cross with an inscription paying tribute to his memory.156 These "markers" are important because they indicate some of the smallest, yet very significant events, that occurred during the battle and they allow tourists to experience the movement and events of the battle as accurately as possible.

Tourist attractions are not only confined to constructed heritage sites but also include natural traces that are of relevance. There are two significant rocks that are found on the summit. The first rock is near the ablution facilities just off of the summit and shows traces of artillery fire from Boer artillery weapon, representing a tangible relic of the event.157 The second rock, which is on a pathway between the mass graves, is of interest because it was here that a young Boer soldier positioned himself as a sniper on the rock and managed to target British soldiers in the trenches with his highly accurate fire - signifying a significant yet intangible aspect of the battle.158 The Battle of Spioenkop is well represented in a number of other associated tourist attractions and these include the Ladysmith Siege Museum in the town; the Talana Museum in Dundee; and the South African National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg.159

Conclusion

According to the former South African Tourism Act No 72 of 1993, no person may be registered as a tourist guide unless he or she has obtained the "requisite knowledge".160 A number of subjects are listed, but significantly history is at the top of the list.161 This is additional evidence which is consistent with the point of this article - the linkages between history, heritage and tourism and how battlefield tourism can invigorate history. Walton suggests that there are two reasons for this possible division between the tourism industry and the academic study of history. Firstly, he claims that the tourism industry has a certain "tardiness" in realising the value of historical studies, and secondly, he considers the discipline of history to have an "innate conservatism" in terms of moving beyond thematic boundaries.162

This is however changing both locally and in the international arena because history departments at academic institutions are embracing tourism as another outlet for the inclusion of history in terms of both the content, but more importantly, the research skills that tourism can impart to history.163 Finally, Albert Grundlingh suggests that there is "sufficient reason to believe that historians should not leave tourism for their summer holidays only, but should also reflect upon the discipline during the academic year"164. Both these historians highlight the potential relevance of tourism to history and vice versa.

1. J. Deacon, "Heritage and African History", in S. Jeppie (ed.), Toward New Histories for South Africa, (Juta, Gariep, 2004), pp 117. [ Links ]

2. V.M. Oberholzer, "'Inclusive or Exclusive?': Heritage and Cultural Tourism in Post Apartheid South Africa", MHCS Dissertation, Department of Historical and Heritage Studies, University of Pretoria, 2012. [ Links ]

3. A. Munslow, Narrative and History (Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, England, 2007), p136. [ Links ]

4. Oberholzer, "'Inclusive or Exclusive?'"

5. J. Carruthers and S. Krige, "Heritage Studies" Study Guide, University of South Africa,Pretoria, 2004. [ Links ]

6. H.E. Stolten, History Making and Present Day Politics: The Meaning of Collective Memory in South Africa (Uppsala, Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2007). [ Links ]

7. E.H. Carr, What is History? Second edition, (Penguin, London, 1990). [ Links ]

8. Carr, What is History?, p30.

9. Carruthers and Krige, "Heritage Studies".

10. Oberholzer, "Inclusive or Exclusive?'

11. Oberholzer, "Inclusive or Exclusive?"

12. C. Saunders, "The Transformation of Heritage in the New South Africa", in Stolten (ed.), History Making and Present Day Politics, p 183.

13. Saunders, "The Transformation of Heritage in the New South Africa", p 183.

14. Government of the Republic of South Africa, The National Heritage Resources Act No. 25 of 1999.

15. The National Heritage Resources Act No. 25 of 1999.

16. Oberholzer, "Inclusive or Exclusive?"

17. Oberholzer, "Inclusive or Exclusive?"

18. The National Heritage Resources Act No. 25 of 1999.

19. Carruthers and Krige, "Heritage Studies".

20. Carruthers and Krige, "Heritage Studies".

21. C. Rassool, "The Rise of Heritage and the Reconstitution of History in South Africa", Kronos, 26, 2000, pp 1-21.

22. A. Curthoys and P. Hamilton, "What Makes History Public?", Public History Review, 1992, pp. 9.

23. Carruthers and Krige, "Heritage Studies".

24. Carruthers and Krige, "Heritage Studies".

25. Rassool, "The Rise of Heritage", pp 5.

26. J. Carruthers, "Heritage and History", Africa Forum, 2, H-Africa, 1998, at http://www.h-net.msu.edu/, Accessed: 28 May 2014.

27. K.H. Ogoti, "Memory and Heritage: The Shimoni Slave Caves in Southern Kenya", PhD. thesis, School of History, Heritage and Society, Deakin University, 2009.

28. R. Wilson, "History, Memory and Heritage", International Journal of Heritage Studies, 15, 4, 2009, pp 374-378. [ Links ]

29. Rassool, "The Rise of Heritage", pp 1-21.

30. G.M.S. Dann and W.F. Theobald, "Tourism: The Nostalgia Industry of the Future", in W.F. Theobald (ed.), Global Tourism: The Next Decade (Butterworth-Heinemann, London, 1995), pp 372. [ Links ]

31. Rassool, "The Rise of Heritage", pp 1-21.

32. Oberholzer, "Inclusive or Exclusive?"

33. Rassool, "The Rise of Heritage", pp 1-21.

34. Ncome Museum and Complex, 2014, at http://www.ncomemuseum.org.za/, Accessed: 14 April 2014; Blood River Heritage Site, 2014, available at http://www.bloedrivier.org.za/. Accessed: 14 April 2014.

35. R. Dunkley, N. Morgan and S. Westwood, "Visiting the Trenches: Exploring Meanings and Motivations in Battlefield Tourism", Tourism Management, 32, 2011, pp 860-868.

36. B. Prideaux, "Echoes of War: Battlefield Tourism", in C. Ryan (ed.), Battlefield Tourism: History, Place and Interpretation, Advances in Tourism Research Studies (Elsevier, Oxford, 2007), pp 17-27.

37. Dunkley, Morgan and Westwood, "Visiting the Trenches", pp 860-868.

38. J.C. Henderson, "War as a Tourist Attraction: The Case of Vietnam",International Journal of Tourism Research, 2, 2000, pp 269-280. [ Links ]

39. National Department of Tourism, National Heritage and Cultural Tourism Strategy (Government of the Republic of South Africa, Pretoria, 2013).

40. National Department of Tourism, National Heritage and Cultural Tourism Strategy, pp. 15.

41. Prideaux, "Echoes of War: Battlefield Tourism", pp 17-27.

42. Dunkley, Morgan and Westwood, "Visiting the Trenches", pp 860-868; M. Foley and J.J. Lennon, "Dark Tourism: An Ethical Dilemma", in M. Foley, G.A. Maxwell and J.J. Lennon (eds), Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure Management: Issues in Strategy and Culture (Cassell, London, 1997), pp 153-164.

43. A.V. Seaton, "War and Thanatourism: Waterloo 1815-1914", Annals of Tourism Research, 26, 1, 1999, pp 15.

44. P. Williams, Memorial Museums: The Global Rush to Commemorate Atrocities (Berg, Oxford, 2007), pp 130.

45. R. Sharpley, "Shedding Light on Dark Tourism: An Introduction", in R. Sharpley and P. Stone (eds), The Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism (Channel View, Bristol, 2009), pp 3-23.

46. Dunkley, Morgan and Westwood, "Visiting the Trenches", pp 860-868.

47. The Battlefields Route, 2014, "The Dundee Diehards", available at http://www.battlefieldsroute.co.za/place/the-dundee-diehards/. Accessed: 19 April 2014.

48. F. Baldwin and R. Sharpley, "Battlefield Tourism: Bringing Organised Violence Back to Life", in Sharpley and Stone (eds), The Darker Side of Travel, pp 186-207; Henderson, "War as a Tourist Attraction: The Case of Vietnam", pp 269-280; J.E. Tunbridge and G.J. Ashworth, Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict (Wiley & Sons, New York, 1996).

49. Prideaux, "Echoes of War: Battlefield Tourism", pp 17-27.

50. Dunkley, Morgan and Westwood, "Visiting the Trenches", pp 860-868.

51. T. Walter, "War Grave Pilgrimage", in I. Reader and T. Walter (eds), Pilgrimage in Popular Culture (Macmillan, Basingstoke, 1993), pp 63-91. [ Links ]

52. Baldwin and Sharpley, "Battlefield Tourism: Bringing Organised Violence Back to Life", pp 186-207.

53. Dunkley, Morgan and Westwood, "Visiting the Trenches", pp 860-868.; Seaton, "War and Thanatourism: Waterloo, 1815-1914", pp 130-158.

54. Battlefields Route, 2014, Internet: http://www.battlefieldsroute.co.za, Accessed: 19 April 2014.

55. Battlefields Route, 2014, Internet: http://www.battlefieldsroute.co.za, Accessed: 19 April 2014.

56. Dunkley, Morgan and Westwood, "Visiting the Trenches", pp 860-868.

57. J. Iles, "Encounters in the Fields: Tourism to the Battlefields of the Western Front", Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 6, 2, 2008, pp 141.

58. Iles, "Encounters in the Fields", pp 142.

59. D. Sherman, The Construction of Memory in Interwar France (Chicago University Press,Chicago, 1999). [ Links ]

60. Iles, "Encounters in the Fields", pp 138-154.

61. J.M. Winter, Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in the European Cultural History (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995). [ Links ]

62. Sharpley and Stone (eds), The Darker Side of Travel.

63. Historic Scotland, "Looking at Heritage: Battlefields", 2011, Internet: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/, Accessed: 15 April 2014.

64. Historic Scotland, "Looking at Heritage: Battlefields", 2011, Internet: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/, Accessed: 15 April 2014.

65. Sharpley, "Shedding Light on Dark Tourism: An Introduction", pp 3-23.

66. Historic Scotland, "Looking at Heritage: Battlefields",2011, Internet: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/, Accessed: 15 April 2014.

67. Baldwin and Sharpley, "Battlefield Tourism: Bringing Organised Violence Back to Life", pp 186-207.

68. A. Meldrum and T. McVeigh, "Murdered in Rorke's Drift, the Man they Called the 'White Zulu'", The Guardian, Sunday 28 January 2007.

69. Historic Scotland, Historic Scotland Environment Policy, 2011, Internet: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/, Accessed: 15 April 2014.

70. Historic Scotland, Historic Scotland Environment Policy, 2011, Internet: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/, Accessed: 15 April 2014.

71. Historic Scotland, Historic Scotland Environment 2011, Internet: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/, Accessed: 15 April 2014.

72. Rassool, "The Rise of Heritage", pp 1-21.

73. Historic Scotland, Historic Scotland Environment Policy, 2011, Internet: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/, Accessed: 15 April 2014.

74. Historic Scotland, Historic Scotland Environment Policy, 2011, Internet: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/, Accessed: 15 April 2014.

75. Carruthers and Krige, "Heritage Studies".

76. Historic Scotland, Historic Scotland Environment Policy, 2011, Internet: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/, Accessed: 15 April 2014.

77. Historic Scotland, Historic Scotland Environment Policy, 2011, Internet: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/, Accessed: 15 April 2014.

78. Historic Scotland, Historic Scotland Environment Policy, 2011, Internet: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/, Accessed :15 April 2014.

79. P. Gough, "That Sacred Turf: War Memorial Gardens as Theatres of War (and Peace)", in R. White (ed.), Monuments and the Millennium (James & James and English Heritage, London, 2001), pp 228-236.

80. Iles, "Encounters in the Fields", pp 142-146.

81. Iles, "Encounters in the Fields", pp 144-145.

82. Dunkley, Morgan and Westwood, "Visiting the Trenches", pp 860-868.

83. Iles, "Encounters in the Fields", pp 138-154.

84. Seaton, "War and Thanatourism: Waterloo 1815-1914", pp 130-158.

85. J. Urry, The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies (Sage, London, 1990). [ Links ]

86. Iles, "Encounters in the Fields", pp 138-154.

87. Gough, "That Sacred Turf', pp 228-236.

88. Gough, "That Sacred Turf', pp 228-236.

89. Iles, "Encounters in the Fields", pp 138-154.

90. Dunkley, Morgan and Westwood, "Visiting the Trenches", pp 860-868.

91. Seaton, "War and Thanatourism: Waterloo 1815-1914", pp 130-158.

92. D.J. Timothy and S.W. Boyd, Heritage Tourism (Pearson Education, Essex, 2003). [ Links ]

93. Timothy and Boyd, Heritage Tourism.

94. For the purposes of this paper the war will be referred to as the Anglo-Boer War and not the South African War. The Anglo-Boer War is the more inclusive term indicating the role played by all sections of South African society. However, the particular battle on which the focus falls in this article, Spioenkop, was fought in Natal and only involved men who were farmers in the region (referred to as "Boers") and the British. This was then indeed a "white man's war" with some 200 to 300 Indians only becoming active in the aftermath of the battle as stretcher bearers of the Royal Ambulance Corps for the British Army.

95. A.M. Grundlingh, "Prelude to the Anglo-Boer War, 1881-1899", in T. Cameron and S.B. Spies (eds), A New Illustrated History of South Africa (Southern Book Publishers, Johannesburg, 1986), p 199.

96. Grundlingh, "Prelude to the Anglo-Boer War, 1881-1899", p 199.

97. T. Pakenham, The Boer War (Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg and Cape Town, 1979). [ Links ]

98. F. Pretorius, The A to Z of the Anglo Boer War (Scarecrow Press, Lanham, 2010). [ Links ]

99. B. Nasson, The War for South Africa: The Anglo Boer War (1899-1902) (NB Publishers, Cape Town, 2011). [ Links ]

100. R. Wyllie, 'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal", BHCS Hons dissertation, Department of Historical and Heritage Studies, University of Pretoria, 2011.

101. Pretorius, The A to Z of the Anglo Boer War.

102. G. Torlage and S. Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal (Ravan Press Johannesburg, 1999). [ Links ]

103. Nasson, The War for South Africa.

104. Pakenham, The Boer War.

105. Wyllie, "'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal".

106. K. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal (Art Publishers, Durban, 2005). [ Links ]

107. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal.

108. Pakenham, The Boer War, p 288.

109. D. Reitz, Commando: A Boer Journal of the Anglo-Boer War (Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg, 1998), pp 64. [ Links ]

110. Pakenham, The Boer War.

111. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal; Pakenham, The Boer War.

112. Pakenham, The Boer War; Pretorius, The A to Z of the Anglo Boer War.

113. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal.

114. Pakenham, The Boer War.

115. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal.

116. Wyllie, "'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal".

117. Pretorius, The A to Z of the Anglo Boer War.

118. Pakenham, The Boer War.

119. Pakenham, The Boer War; Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal; Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal; Wyllie, "'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal".

120. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal.

121. Pakenham, The Boer War.

122. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal; Wyllie, "'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal".

123. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal Pakenham, The Boer War.

124. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal; Wyllie, "'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal"; Pakenham, The Boer War.

125. Wyllie, "'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal".

126. Pakenham, The Boer War.

127. Pakenham, The Boer War, Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal.

128. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal.

129. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal; Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal.

130. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal.

131. Wyllie, "'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal".

132. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal.

133. Pakenham, The Boer War, Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal.

134. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal; Pakenham, The Boer War.

135. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal; Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal.

136. Pakenham, The Boer War.

137. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal; Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal; Wyllie, "'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal".

138. Pakenham, The Boer War.

139. K. Gillings, Tourist guide and friend, Verbal communication with author, 3 July 2011. Spioenkop tour, Notes in possession of the author.

140. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal.

141. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal; Wyllie, "'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal".

142. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal; Battlefields Route Association, 2011, "Explore the Largest Concentration of Battlefields and Game Parks in Southern Africa", Internet: http://www.battlefields-route.co.za, Accessed: 23 August 2011.

143. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal.

144. Pakenham, The Boer War.

145. "Ghosts Still Haunt Spioenkop Battlefields", Independent Newspapers, 23 January 2001, Internet: http://www.iol.co.za/travel/south-africa/ghosts-still-haunt-spioenkop-battlefields/. Accessed: 6 June 2014, pp. 1.

146. Battlefields Route Association, 2011, "Explore the Largest Concentration of Battlefields and Game Parks in Southern Africa", Internet: http://www.battlefields-route.co.za, Accessed: 23 August 2011.

147. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Nata; Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal.

148. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal; Wyllie, "'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal".

149. Tourism KZN, "2013 Tourism Statistics of our Tourism Sector", Internet: http://www.zulu.org.za, Accessed: 28 May 2014.

150. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Nata; Wyllie, "'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal".

151. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal.

152. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal; Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal.

153. Gillings, Battles of KwaZulu Natal.

154. Torlage and Watt, A Guide to the Anglo-Boer War Sites of KwaZulu Natal; Wyllie, "'Victor Belum': An Appraisal of Battlefield Tourism in KwaZulu Natal".

155. Battlefields Route Association, 2011, "Explore the Largest Concentration of Battlefields and Game Parks in Southern Africa", Internet: http://www.battlefields-route.co.za, Accessed: 23 August 2011.

156. K. Gillings, Verbal communication with author 3 July 2011. Notes in possession of the author.

157. K. Gillings, Verbal communication with author 3 July 2011. Notes in possession of the author.

158. K. Gillings, Verbal communication with author 3 July 2011. Notes in possession of the author.

159. S. Derwent, A Guide to Cultural Tourism in South Africa (Struik Publishers, Johannesburg, 1999). [ Links ]

160. School of Law, University of Witwatersrand, Annual Survey of South African Law 1993 (Juta & Co., Cape Town, 1993).

161. Government of the Republic of South Africa, Tourism Act No. 72 of 1993.

162. J.K. Walton, Histories of Tourism: Representation, Identity and Conflict (Channel View Publications, Clevedon, 2005) pp 563-571; [ Links ] A.M. Grundlingh, "Revisiting the 'Old' South Africa: Excursions into South Africa's Tourist History under Apartheid, 1948-1990", South African Historical Journal, 56, 2006, pp 103-122. [ Links ]

163. Faculty of Humanities (Undergraduate) Regulations and Study Programs, Department of Historical and Heritage Studies, BHCS in Heritage and Cultural Tourism, University of Pretoria, 2014, pp 44-45.

164. Grundlingh, "Revisiting the 'Old' South Africa", pp 104.