Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Historia

versão On-line ISSN 2309-8392

versão impressa ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.58 no.2 Durban Jan. 2013

ARTICLES ARTIKELS

Creating order and stability? The Dairy Marketing Board, milk (over)production and the politics of marketing in colonial Zimbabwe, 1952-1970s

Godfrey Hove

Post-graduate student in economic and environmental history, studying towards a PhD degree at Stellenbosch University's History Department. His current research focuses on Zimbabwe's agrarian history, particularly dairy farming. The author is particularly grateful to Victor Machingaidze for the supervision of his MA in the Economic History Department, University of Zimbabwe, on which this article largely draws. Email: godfreyh72@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This article examines the efforts of the Dairy Marketing Board (DMB) in stabilising the dairy industry in the wake of difficulties that emerged in the production and marketing of dairy products after World War Two. It traces and evaluates the marketing and distribution strategies the DMB used, and their strengths and weaknesses. It illustrates the point that while shortages which had characterised war-time and post-war Southern Rhodesia had been eliminated by the mid 1950s, continued increased production led to over production which in turn created serious challenges for the Board in finding markets for the lucrative liquid milk trade. This article analyses the general national policy of self sufficiency in agricultural production that was espoused during the course of the war and were pursued vigorously after the war. It argues that this policy was not feasible for the dairy sector because it proved cheaper to import cheese and skimmed milk powder than to produce it locally. It is also maintains that while the voluntary takeover and recapitalisation of struggling private concerns on the distribution side was necessary in the 1950s, the employment of legislative instruments to elbow private concerns out of the milk market from the 1960s onwards was not in the best interests of the industry. Instead, these tactics were aimed at placating the DMB financially - a move that was unfair to both private players and consumers.

Key words: Dairy Marketing Board, Dairy Farmers, Marketing, Production, Producer-Retailers, Milk

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel ondersoek die pogings van die Suiwel Bemarkingsraad (Dairy Marketing Board [DMB]) om, in die lig van die produksie en bemarkings probleme wat in die vaarwater van die Tweede Wereldoorlog ervaar is, die suiwelbedryf te stabiliseer. Dit ondersoek en evalueer die sterk en swakpunte van die bemarkings en verspreidings strategieë wat die Raad gebruik het. Die artikel argumenteer dat hoewel die tekorte wat tydens en direk na die oorlog in Suid-Rhodesië ondervind is teen die middel vyftigerjare uitgeskakel is, die voortgesette toename in produksie tot oorproduksie gelei het. Hierdie oorproduksie het die Raad genoodsaak om nuwe markte vir die winsgewende handel in vloeibare melk te vind. Hierdie studie analiseer die algemene nasionale beleid van selfvoorsienendheid ten opsigte van landbouproduksie wat tydens die oorlog beslag gekry het en na die oorlog doelgerig nagestreef is. Die referaat argumenteer dat die beleid in die lig van die beskikbaarheid van goedkoper ingevoerde kaas en afgeroomde poeiermelk, nie vir die suiwelbedryf haalbaar was nie. Dit word ook geargumenteer dat terwyl die vrywillige oorname en die herkapitalisering van sukkelende privaat verspreiders van suiwelprodukte noodsaaklik was in die 1950's, die aanwending van wetgewing in die 1960's om privaat produsente uit die melkmark te dryf nie in die bedryf se beste belang was nie. Die taktiek wat daarop gemik was om die Raad finansieel ter wille te wees was onregverdig teenoor beide die privaat rolspelers as die verbruikers.

Sleutelwoorde: Suiwel Bemarkingraad; Suiwelboere, Bemarking, Produksie, Produsent-kleinhandelaars, Melk.

Introduction

The operation of marketing boards in colonial Africa has received significant scholarly attention. The commodity marketing boards that were established in West Africa have invited a great deal of historical inquiry, with scholars such as J.O. Ahazuem and T. Falola criticising them for their exploitative role as "tax-gatherers"1 for colonial governments. P.T. Bauer argues along more or less the same lines, contending that although the boards were ostensibly established to stabilise prices, this, in reality, was not the case because the boards turned out to be "instruments of robbery", with farmers in both the Gold Coast and Nigeria consistently being paid prices well below the world market price.2 Prices actually became more unstable under the marketing board system than they had been prior to their formation. Instead of using the funds accumulated from the farmers to develop agriculture, scholars like A.G. Hopkins state that the funds were used for other projects largely unrelated to their origin.3 In this case, boards such as the West African Cocoa Control Board and the West African Control Board established in the Gold Coast in the 1940s served to exploit African producers to the advantage of the colonial state, and ultimately metropolitan Britain.

For colonial Zimbabwe, most of the historiography on marketing boards, and agriculture in general, has focused on the maize, beef and tobacco industries, thus relegating other forms of agriculture to the fringes. I. Phimister and V. Kwashirai's studies focus on the development of the beef industry under monopoly marketing companies and the role of the Imperial Cold Storage Company in the marketing of beef respectively.4 These two studies examine the circumstances leading to the development of monopolies in the beef industry as well as the underdevelopment of African cattle production in the period prior to the Second World War. There are similar studies on maize production and marketing in Zimbabwe. E. Makombe has also written on the role of the Grain Marketing Board in the maize industry in colonial Zimbabwe. His work largely focuses on the pricing aspect and its impact on settler producers.5 He argues that the price policies pursued in Southern Rhodesia did not achieve the intended goal of stabilising production trends in the country. He also concludes that in the final analysis, the state did not offer settler producers "reasonable" price stability, despite efforts to rope African maize producers in to subsidise settler maize exports.6 M.C. Runhare's study discusses the marketing of maize under the Grain Marketing Board in the Lalapanzi area between 1990 and 2001.7 He focuses on the impact of the liberalisation of the marketing of maize in Zimbabwe and its impact on small-scale producers.

While the historiographical bias towards maize, tobacco and beef may easily be rationalised by the fact that the three industries were the lynchpin around which the colonial economy rotated for much of the colonial period,8 the success of other agricultural enterprises was vitally important for a colony whose ambition was to attain food self-sufficiency. Indeed, it is contended here that although they contributed less to the national income than did maize, tobacco and beef production, the "lesser" branches of agriculture provide an equally important lens through which some interesting dynamics of the Southern Rhodesian socio-economic and political developments can be viewed. The development of post- Second World War dairy farming under the Dairy Marketing Board (DMB) illuminates some interesting facets of the anatomy of the Southern Rhodesian political economy.

In examining the role played by the DMB in the production and, to a larger extent, marketing of milk, this article analyses the role played by the statutory bodies that were formed to deal with wartime and post-war shortages of agricultural products in Southern Rhodesia. These boards also endeavoured to re-organise product handling and distribution systems that were failing to cope with increased post-war production and consumption. The article argues that by taking over many struggling co-operative dairies and creameries and providing a guaranteed market for all milk and butterfat at fixed high prices, the DMB helped to stabilise and grow the industry. Indeed, production increased phenomenally, and by 1956, shortages had been eliminated. However, the paper also contends that the DMB later became a victim of its policy of using price incentives to induce farmers to produce more, leading to serious viability woes from the late 1950s onwards.

From about 1956, signs of milk over-production had begun to appear, and this ushered in a period of stress for farmers and the DMB. For producers, it led to falling prices because with the whole milk market saturated, more and more of the farmers' milk was converted into less remunerative products such as cheese and skim milk powder and the government was unable to subsidise farmers under the difficult economic conditions of the time. For the DMB, conversion of surplus milk led to reduced profits (and losses in some cases), while efforts to find markets for the more lucrative whole milk business were unsuccessful. Whereas the commercial dairy sector had depended on the growing settler population for consumption after the war, a steady decline in the settler immigration rate from the 1960s onwards, coupled with a burgeoning African urban presence as a result of the post-war industrial boom, meant that the exploration and development of the African urban population as a potential market for both agricultural and industrial products became an increasingly inevitable economic necessity. It will be argued that more than any other reason, the vigorous pursuit of the African market and the elimination of competitors (particularly producer-retailers who marketed their milk in urban centres from the late 1950s), led to the government's efforts to ensure the DMB's profitability in the wake of the hostile economic conditions that began in the 1960s and stretched into the 1970s.

Post-World War Two developments

The advent of the Second World War in 1939 radically altered the disposal pattern, if not the entire structural organisation of the dairy industry. Whereas dairymen had long depended on the export trade for the disposal of their products, the rapid increase in white population during and after the war years led to a corresponding increase in the local demand for dairy products. Shortly after the outbreak of the war, a number of military centres were established in the main centres of the country. Royal Air Force training centres sprang up in Salisbury, Bulawayo and Gwelo, and these were responsible for the arrival of about 20 000 Royal Air Force personnel, their wives and families into the country. In addition, at least 6 000 internees and refugees had settled in Southern Rhodesia by 1945.9 Consequently, considerable quantities of milk which would normally have been converted into butter and cheese for export had to be diverted to the local fresh milk trade. In fact, a shortfall between production and consumption of dairy products, particularly butter and milk had begun to emerge by 1942. Because the country was, for the first time, failing to satisfy local demand, it was faced with a need to import butter and cheese as virtually all milk was sold on the fresh milk market. However, the war itself made importing very difficult due to wartime disturbances and restrictions, and it became clear to the Dairy Control Board, which had been formed in 1931 in response to the depression-induced hardships, that the only viable option was to increase production and become self-sufficient.

The accelerated rate of white immigration after the Second World War exerted greater pressure on the dairy industry. Some of the white immigrants were former British soldiers who were attracted by the incentives offered by the government's post-war settlement scheme, while some were former trainees under the Royal Air Force training scheme who decided to settle in the country permanently.10 Also, a great number of white immigrants were fleeing the harsh post-war economic conditions in Britain and were optimistic of better prospects in a country whose policies were heavily biased in favour of white settlers.11

This placed great strain upon the dairy industry, and an acute problem in catering for the future milk requirements of the rapidly expanding European population was inevitable. This problem arose partly because of the low prices that were offered to producers, and largely as a result of the nature of the milk distribution system that existed in the country. In response to the low producer prices that had perennially been paid to farmers since the onset of the Great Depression, under the Dairy Act of 1937 the Dairy Industry Control Board was empowered to fix minimum and maximum prices to be paid to producers. Further, in efforts to stimulate production in the face of shortages induced by the Second World War, the Dairy Control Board in 1943 established a price equalisation scheme, and followed this up with a dairy bonus scheme in 1945 whose aims were to "encourage winter production by a substantially increased price for butterfat and milk produced during this period" and to encourage the production of good quality milk and butterfat by offering bonuses for first grade butterfat respectively. Although producer prices became somewhat higher owing to these schemes, the fact that they were merely short term remedies meant that few prospective dairy farmers were prepared to make long term investments in the industry. The schemes had the effect of inducing existing farmers to increase production, thus leading to nominal milk and butterfat production increases.

On the distribution side, overall responsibility for production patterns and marketing arrangements was placed in the hands of the government through the Minister of Lands and Agriculture, while the role of municipal authorities was limited only to milk produced in their areas of jurisdiction.12 However, virtually all creameries and dairies that received, processed and distributed milk and other milk related products were run by farmer-owned co-operative concerns. Owing to limited capital, and the generally low profit margins they had worked with since the late 1920s,13 their milk handling facilities, which could only be improved piecemeal during the war owing to scarce equipment and supplies, were inadequate to handle larger volumes of milk that had been anticipated for post-War Southern Rhodesia.

In response to their limited handling capacity, the co-operative enterprises had, by 1952, developed monopolistic tendencies in that the entry of new producers into the liquid milk market was made difficult by a whole milk quota system.14 In this case, new supplies could only gain entry after sales had increased, rather than in anticipation of growth.15 The quota system had the effect of barring new entrants into the industry, while existing producers were discouraged from expanding production. In these conditions, fresh milk tended to be in short supply. Given the fast increasing population and the demand for milk and other dairy products, something had to be done urgently to redress the situation.16

In an effort to resolve the problem, two official inquiries were conducted - the Milk Subsidy Committee in 194717 and a Parliamentary Select Committee in 194918 - from which an entirely new organisational structure was conceived. With a projected European population growth to almost 200 000 by 1956 in mind, the two committees recommended the establishment of a statutory milk commission which would initially concentrate on securing milk for the large cities where needs were most pressing, and thereafter, with government finance, would expropriate and compensate existing milk handling enterprises. It would also build new factories and processing plants where necessary. It also advocated a longterm producer price policy with payment according to the quality of milk produced.19 By and large, most of these recommendations were adopted, and a non-statutory Milk Marketing Committee was established in 1949. It was charged with buying milk direct from the producers and selling it to distributors. In the buoyant economic conditions of the time, Land Bank loans were made available to intending dairymen so that a material improvement in raw milk supplies was almost inevitable. Indeed, this led to a material increase in raw milk supplies, output rising by over 3 million gallons to 10.1 million gallons in 1951 from 7.2 million in 1946.20

As more milk and butter were delivered to them by farmers, the ability of co-operative dairies to handle, process and distribute milk and other products was severely strained. Disruptions which continued to occur in the handling and distribution, coupled with seasonal milk shortages which persisted in most centres, seemed to point to a complete distribution breakdown.21 Partly as a result of the wartime hardships, and mainly due to long term shortages of capital, the processing plants of most creameries and co-operative dairies were either too old to function properly or generally too small to accommodate increasing milk intake, or both.

In response to the marketing problems, which at this time affected virtually every agricultural industry in Southern Rhodesia, in 1951 the government passed the Agricultural Marketing Act, providing for the establishment of marketing schemes to regulate the marketing of agricultural products. This Act gave birth to the Agricultural Marketing Council (AMC) whose main duty was to examine and advise the Minister of Agriculture and Lands on issues to do with pricing, import and export of agricultural products and the formation of marketing schemes for all agricultural sectors.22 It was within this framework that the Dairy Marketing Scheme was created and introduced with effect from the first day of October 1952. Under this scheme, the Dairy Marketing Board was formed on the same day, hence abolishing the Dairy Control Board.23 The DMB was empowered to purchase all manner of dairy products, to process, distribute and import them, as well as to erect and operate dairy plants in Southern Rhodesia.

Revival and stabilisation: Production and marketing trends under the Dairy Marketing Board to 1956

When the DMB began operations, most dairies and creameries were evidently struggling to stay afloat. In its 1953/54 report, the Board noted that most of the producers' co-operative companies were in "a parlous state, all except one were losing money and lacked capital for necessary improvement".24 The only exception was the Model Dairy in Bulawayo which had undergone refurbishment in 1948. With the government controlling the consumer prices of dairy products, the co-operative companies could not raise adequate resources from their businesses to re-capitalise their operations and cater for the increasing supplies of milk. Thus, it was partly because of their limited capacity that they adopted a "closed shop" attitude towards new entrants into the industry. Shortly after the DMB's establishment, the Dairymen's Co-operative, which had been servicing Salisbury, gave notice to go into liquidation. The Board took over its operations, and hence immediately became involved in the retailing of milk and other dairy products.25 Although the DMB had initially sought to use private enterprise in large centres as its agents in the distribution of milk, it quickly learnt that this was not possible at this stage.26 The margin allowed proved very unattractive to private enterprise and this forced the Board to organise its own distribution. Indeed, during the debate on the motion to approve the marketing scheme in the colony's parliament in 1952, the Minister of Agriculture and Lands claimed that the handling of milk on a retail basis was "forced" on the DMB by the Dairymen's Co-op going into liquidation, and that "it was not intended that it should be one of its functions. Already the Board is considering the question of ridding itself of the distribution in this centre."27

With the benefit of hindsight, however, it may be said that the DMB made few, if any attempts to rid itself of distribution. Actually, it did the opposite. As more dairies in other centres "availed themselves" for liquidation, the Board successfully appealed to the government for the release of funds to enable it to purchase more dairies and take over their operations. The DMB was convinced that the best way to establish the industry on a more solid footing was by taking over the dairies, creameries and factories and re-capitalising them. Writing in 1953, the chairman of the DMB, T.C. Pascoe argued:

It has already become apparent that the industry cannot be operated at maximum efficiency in the interest of the consumers and producers alike, until the Board assumes direct control of the processing of milk, butter and cheese throughout the colony. Only by this means can it satisfactorily rationalise the industry ... there are indications that the independent producer co-operatives would not be unwilling to see their activities taken over ... so that the whole industry can be operated as one single economic unit.28

This argument makes sense only if it is taken to mean that all struggling co-operative companies that voluntarily went into liquidation should be purchased and taken over by the DMB in the interest of producers and consumers. Given the unprofitable nature of their operations, most co-operative companies were indeed prepared to hand themselves over to the Board for a fee at the time, and many did. However, also unmistakable from Pascoe's statement is the underlying inference that that the Board should be the only player in the industry. As will be shown later in this article, this posture gradually developed into a policy of active involvement by the Board from the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. From its early days, therefore, the DMB became the chief distributor of milk in the main centres, with the remainder being distributed by producer-retailers who took advantage of their geographical location to enter into the retail trade in the major centres.29 By 1960, the only remaining private dairy processing enterprises operational which pre-date the DMB were the small co-operative cheese factory at Chipinga; a private butter factory at Umtali; and a small proprietary dairy at Fort Victoria which operated as an agent of the DMB for the distribution of milk. In total, the Board expended about £578 000 on the purchase of the co-operative businesses, which finance was provided by the government in the form of long-term loans.30

The takeover of many of the struggling dairy processing enterprises had the effect of reviving the interest of prospective dairymen. Most settlers who had intended to engage in dairy farming prior to these developments had been frustrated by the "closed shop" attitude of the co-operatives which manifested itself in a quota system being introduced for new producers.31 When the Board took over these dairies, it abolished this system because constitutionally it was obliged to accept all the milk that was delivered to it. It is not surprising therefore, that many of the interested settler farmers, who had been closed out by the parochial approach of the co-operatives, joined the industry after 1952. While there were only 359 registered whole milk producers in Southern Rhodesia in 1952, this number had risen to 526 by 1957.32 Without doubt, the availability of a guaranteed market for milk and butter lured some formerly hesitant settlers into dairying. It also gave the existing farmers the much needed confidence to increase production. They had the assurance of a market for all their milk and butterfat.

After taking over most of the dairy processing enterprises from private co-operatives, it soon became apparent to the Dairy Marketing Board that their processing facilities were wholly inadequate to cater for the growing volume of milk received. Most co-operatives had inadequate resources to modernise their facilities, particularly because the cost of a dairy plant is probably higher, in relation to the returns on capital, than in almost any other agricultural industry. The Board thus had to embark on a major expansion and modernisation drive in virtually all the dairies it purchased. In Salisbury (now Harare), for example, which received the highest average daily intake of milk, the Board had inherited a dilapidated dairy. Unsuccessful efforts by the Dairymen's Co-op to refurbish the dairy led to a scenario where the Board had to take over a partially completed facility which needed a major facelift. In his outline of the problems at the Salisbury dairy, W. Sandford, the Board's first chairman, complained:

Although the Board was able to commence the processing of whole milk in the Manica Road Dairy on the 1st of December 1952, the installation of the plant and the alterations to the building were by no means complete. Considerable trouble was experienced with the bottle washing machine which was damaged by a subsidence of the conditions and there was further trouble with the refrigerating plant due to inexperienced workmanship in the installation.33

The situation was further aggravated by the fact that the cheese factory had long broken down so that the Board had to make makeshift arrangements for the manufacture of cheese which was done in the ice cream section of the dairy.34 The cheese section was only resuscitated in February 1953 at a time when the summer "flush" season was almost coming to an end and when less milk had to be converted into cheese. However, despite the massive additions and buildings that were made, it was apparent that the Salisbury dairy, given the ever increasing volume of milk that was delivered to it, would still be inadequate to meet whole milk requirements in the near future. The Board consequently applied to the Salisbury municipality for a more conducive site which would facilitate the establishment of an improved and much larger facility for the handling of whole milk and the manufacture of other dairy products. However, due to the rigorous bureaucratic procedures that the Board had to follow in acquiring the land from the local authority and the requisite funds from the government, the new Salisbury dairy was only commissioned in February 1959.35 By this time, the dairy could barely handle the milk delivered comfortably, with the result that the quality of milk deteriorated at the dairy, particularly during the summer.

It was thus evident that the other dairies which the Board had taken over from the Rhodesia Co-operative creameries in Gwelo, Que Que and Umtali were hardly suitable for use in the interest of both the consumers and the producers. In July 1953 the Board had the advice of R. Dibsdale, an engineer of the Aluminium & Vessel Company, who undertook a survey of the colony's dairy processing plants and submitted a report on its requirements for the next ten to fifteen years. Dibsdale recommended that inter-alia, the Gwelo and Umtali dairies could only be regarded as makeshift until entirely new dairies are constructed.36 In addition, he noted that the Que Que dairy, although relatively better than those at Gwelo and Umtali, was too antiquated for the present circumstances and needed refurbishment. So dire was the situation at these dairies that the Board was at times forced to transfer milk to the already overburdened Salisbury dairy during the flush seasons, only for the milk to be sent back during times of shortages.

In fact, private dairies also came to the rescue of the Board's dairies by accepting their milk for processing. For instance, the Model Dairy in Bulawayo (before it was taken over by the Board) accepted milk from the dairy in Gwelo and the Bulawayo Creamery and converted this milk into cheese for sale to the public.37 However, being a private concern, it could hardly be expected to assist the Board if this assistance were to lead to losses for the company. For example, during the 1953/54 milk flush season,38 this dairy was unable to accept the surplus milk normally sent to it from Gwelo because of the very small margin allowed for manufacturing cheese. These supplies were sent to the Salisbury dairy instead, despite the fact that the Salisbury dairy was already receiving qualities of milk far in excess of its capacity.39

Owing to the parlous state of the dairies, plans were therefore drawn up by the Dairy Marketing Board for a new dairy, creamery and cheese factory at Gwelo; and a new dairy and cheese factory at Umtali. A satisfactory five-acre site was secured from the Cold Storage Commission in Gwelo, while the Umtali local authority sold a suitable piece of land to the Board for the construction of the facilities. The construction of the two dairies was completed in 1955 at a combined cost of £155 000.40 A new dairy plant was also installed at Que Que during the year with the result that the existing plant had to be closed down completely for about six months while the new facility was being installed. During this period, bottled milk had to be transferred from Gwelo each morning, the lorry returning to Gwelo with the bulk milk which producers in the Que Que catchment area delivered. Inevitably, this led to huge financial losses; so much that the Gwelo and Que Que dairies incurred a combined loss of £4 132 in that year.41

The new Gwelo dairy subsequently became the largest in the country during the 1950s - it was able to bottle up to 3 000 gallons of milk per day and could also convert 1 000 gallons of milk into cheese and the equivalent of 22 000 gallons of milk could be converted into butter and skim milk powder in a day.42 In fact, the dairy became the de facto headquarter of milk products, since both the Salisbury and Bulawayo dairies began to send surplus milk there for conversion into butter and skim milk from 1955 onwards.

Without doubt, these capital projects went a long way towards modernising the processing and equitable distribution of milk and other dairy products. Indeed, a Commission of Inquiry set up in 1961 to investigate the dairy industry, reported in 1962 that it was "impressed with the plants, which are first-rate, and [with] the spotless way everything was built".43 These developments also played an important role in boosting the confidence of the producers in the future of the industry.

Prices

Dairying, being a long-term project, needs stability of producer prices if the confidence of producers is to be assured. It is not necessarily important that the price should always be high, providing it does not fluctuate too much and thereby affect the confidence of producers. Given the high incidence of shortages of milk and milk products in Southern Rhodesia when the DMB was formed, it was necessary that steps be taken to incentivise milk and butterfat production and thus boost producer confidence. At the same time, the government was anxious to keep the consumer prices of whole milk and other products (such as cheese, butter and skim milk powder) low. In fact, the government sought to maintain the cost of living as low as possible to attract white settlement in the aftermath of the Second World War. In addition to providing farmers with an assured market in the form of the DMB, the government took steps to ensure that producer prices were fixed at an attractive level during the early years of the Board's operation. The Board had little say in the determination of the prices it paid to the producers; they were negotiated from time to time between the government (as advised by the Agricultural Marketing Council), and the Rhodesian National Farmers' Union (RNFU).44

The pricing of milk to products was not uniform throughout the year. In line with standard international practice in the major dairying countries, the government continued the system of paying higher prices during the winter season in order to encourage production during that time. For the 1952/1953 season, for instance, the Board paid 2/6d per gallon in summer and this went up to 3/9d per gallon in winter.45 These prices, which were fixed with a view to increase producer confidence, were negotiated on an annual basis. However, there were very few fluctuations to the price paid to producers until 1957. This was despite the fact that prices on the international market were highly volatile throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

It is also important to note that the prices paid to farmers during this time were slightly higher in comparison to what farmers elsewhere were earning. For instance, the New Zealand dairymen, who were generally more efficient compared to their Southern Rhodesian counterparts, were paid an average of 3/5d per gallon during the July to November winter in 1953, while dairy farmers in the Union of South Africa received 3/4d per gallon during the same season of the year.46 This is a clear indication that in the 1950s the Southern Rhodesian government was determined to go out of its way to encourage production. Although the dairy industry during that time was not as lucrative as any of the three major agricultural sectors, that is, tobacco, maize and beef, the price incentive offered was still attractive enough to entice some of the immigrant settlers to embark on dairying. In addition, the farmers who had already invested in dairying were encouraged to increase the extent of their investments because of the high producer prices. The result was that the number of dairy farmers in the colony more than doubled between 1952 and 1961. Shortages, which had characterised the 1940s, were eliminated by the end of 1954, and by 1956 a significant surplus was beginning to be witnessed, even during the winter seasons.47 Production targets and estimates in the 1950s were easily surpassed within shorter periods of time. In the Board's second annual report in 1954, for example, it was estimated that 8 300 000 gallons of milk would be handled by the Board's dairies in 1956, whereas actual receipts for that year were 9 530 000.48 Whereas the Salisbury dairy handled an average of 8 200 gallons of milk per day in 1953/54, it was handling an average of about 13 700 gallons per day during 1956/57.

Increasing milk production levels over and above national whole milk requirements meant that a bigger proportion of milk had to be processed into cheese and skim milk. For instance, while only 14.7% of the 6.11 million gallons delivered to the Board were converted into cheese and skim milk during the 1953/44 season, about 31.5% of the 9.53 gallons delivered to the Board were processed into cheese and skim milk in 1956/57.49 Initially, this was not difficult for the Board because of its enlarged and improved cheese making facilities particularly at its Gwelo, Salisbury and Umtali dairies. In fact, the gallonage of milk that was set aside for cheese manufacture was always on the rise during the period to 1957. This can be illustrated by the fact that while only 1 397 857 gallons were used in the manufacture of cheese in 1955, about 2 266 900 gallons were devoted to cheese manufacture by 1957.50

The conversion of an increasing proportion of milk into cheese became crucial in reducing the import burden of the Board. Prior to 1955, Southern Rhodesia had to import large quantities of cheese from South Africa and Kenya in an attempt to supplement the shortages on the local market. As a result of the conversion of large quantities of milk into cheese, particularly during the flush season, and the improved cheese making facilities, the Board was able to manufacture sufficient quantities of Cheddar and Gouda cheese for the home market without the necessity to import.51 The level of cheese production in the country was also boosted by the Gazaland co-operative cheese factories in Chipinga, which was the only private concern in the cheese making business at the time.

With time, however, the Board was compelled to manufacture more cheese than it could reasonably expect to dispose of. This was despite the fact that cheese sales were growing at a steady rate within the colony. Two factors account for this. Firstly, the ever increasing intake of milk from producers over and above whole milk requirements pushed the Board to convert more milk into cheese despite its knowledge of the inelasticity of the market for this product. The substantial rise in milk deliveries (which milk the Board was obliged to accept) particularly during the 1956/57 flush season, strained the Board's milk storage facilities so much that it just converted it into cheese without due regard for the limited market for cheese. It should be noted, however, that this occurred only during flush seasons when the amount of milk delivered to the Board was at a peak. Secondly, the margin which cheese retailers were allowed was too low. This meant that many retailers were dissuaded from purchasing cheese from the Board; they preferred instead to sell imported cheese because its wholesale price was not subject to local price control. In terms of price control regulations, retailers only received a small margin of 4d per lb on locally produced cheese.52 The result of this, of course, was that Southern Rhodesia continued to import cheese even during the flush seasons when her local production was sufficient to meet domestic needs.

The overall effect of increased cheese manufacture, especially during the flush season, against the background of a limited local market was that huge stocks of cheese were piled up at most DMB dairies. T.C. Pascoe's comment on this issue at the end of the 1955/56 year illustrates the situation. He said:

Although it was possible to convert most of the surplus [milk] into cheese, there was approximately a five month stock of cheese in the Colony at the end of the period which resulted in available facilities being taxed to the utmost. In Que Que, this necessitated renting extra storage space.53

Owing to its keeping qualities, that is, the time frame within which the cheese would retain its freshness, most of the cheese deteriorated in quality as it lay stockpiled at the dairies. Despite strenuous efforts to dispose of surplus cheese by increasing exports to South Africa and Northern Rhodesia,54 older cheese developed internal mould which resulted in slightly reduced price realisation to the Board.131 There were, however, sporadic shortages of cheese in winter at some dairies in Bulawayo and Fort Victoria, and it was during this time that the Board either attempted to dispose of the deteriorated stocks or resorted to importing. It thus became an annual pattern to export surplus stocks in April or May of each year and to import any shortfall each October.55

A more serious problem with cheese production, however, was the low profit realisation it afforded the Board itself. With both wholesale and retail cheese prices controlled by the government, the Board found itself making losses through the manufacture of cheese. In fact, so narrow were the margins allowed that the Board itself was selling first grade cheese to retailers at about cost, while second and third grade butter was sold at a definite loss.56 This low profit realisation by the Board was further aggravated by the fact that the DMB at times sold old cheese whose quality had deteriorated; and that retailers were unwilling to purchase the Board's cheese, even the higher grade product, preferring, as mentioned above, to trade in imported cheese because its wholesale price was not subject to local price control.

It was in this light that the Board turned to whole milk and skim milk (both liquid and powder) in an attempt to improve its financial standing. The manufacture of skim milk was done particularly with the urban Africans in mind. The words of T.C Pascoe in 1956 serve to shed light on to the official thinking at the time. He stated that:

The Board is determined to convert the African into a milk consumer, not only to assist in utilising the ever increasing milk surplus, but also to improve the general health of this section of the population. For some time to come, this aim can best be achieved by making wholesome skim milk, rather than whole milk, readily available to the African at a price which he can afford.57

While it may be true that as Pascoe's statement above shows, the Board was also concerned about improving the diet and general health of urban Africans, it may also be contended that the Board's primary concern was finding outlets for its surplus milk. As will be illustrated later in this article, the fast rising African urban population was just one of the many outlets the increasingly desperate Board looked to as a potential market for liquid milk.

With a view to increasing sales and luring Africans into buying its dairy products, in 1956 the Board decided to sell liquid skim milk and cultured lactic milk, which was popularly referred to as "lacto", at sub-economic prices. With time, however, when consumers seemed to have "accepted" the products, the prices were raised to more economic levels in 1957.58 Although sales of both liquid skim milk and "lacto" decreased slightly following price increases from 4d per pint to 4.5d per pint, they began to show a tendency to increase during the ensuing years as Africans began to "adjust" to the prices. After all, the prices were still far lower than that of whole milk whose price was pegged at 6d per pint for sales in quantities of less than 3 gallons at a time.59

In February 1956, the DMB purchased two second hand units for the purpose of converting part of the surplus milk into skimmed milk powder. These units, which were installed at the dairy in Gwelo, began production the following month. As with liquid skim milk and "lacto", the target market for skim milk largely comprised but was not restricted to urban Africans. A report by independent analysts concerning the quality of the product stated that it "compare[d] favourably with imported roller dried skimmed milk powder".60 This product, which the analysts described as being of the "utmost value for the African diet from a nutritional aspect", was marketed throughout the colony at a price considerably lower than the price of whole milk in one pint packets.61 In addition to African consumption, however, skimmed milk powder was also marketed to dairy farmers and beef cattle ranches in bags for use as stock feed. As part of efforts to help dairy farmers, skimmed milk powder was sold to registered milk producers at a much reduced price.62

Sales of skimmed milk powder remained lower than expected. The major obstacle which prevented a significant rise in sales was the very low prices at which this powder was imported into Southern Rhodesia from countries such as New Zealand and Canada. This was a result of the low production costs in those countries. The proliferation of cheap (and possibly better quality) imported skimmed milk powder worked to the disadvantage of local products.63 Unsuccessful representations were made to the federal government that it should place a duty on the imported product. The frustration of the DMB with this situation is seen in the following statement by T.C. Pascoe:

It is considered inequitable that the Board should have to contend with external competition whilst handling a rapidly increasing milk surplus. Representations made to the government with a view to giving the local product the necessary tariff protection have so far proved unsuccessful.Surely, this is working to the detriment of the colony's industry.64

Representations to the government only bore fruit as late as 1962, when restrictions on the importation of milk powder were introduced. Prior to this development, huge stocks of locally made skimmed milk powder were piling up at most dairies with the result that the Board had to reduce the price at which it sold to registered milk producers to sub-economic levels.65 From the Board's point of view, one advantage of the conversion of milk into skim milk, however, was that it increased the amount of butterfat that could be separated for butter manufacture. It was for this reason that few incentives were made available for increased butter production. As butterfat manufacture decreased from the late 1950s onwards, albeit as a result of increased skim milk production, butter imports from New Zealand and South Africa began to decline considerably.

From buoyancy to crisis: Production and marketing, 1957-1970s

From the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, the fortunes of the dairy industry were evidently nose-diving. The buoyancy that had characterised the early 1950s slowly began to give way to a looming crisis for both the DMB and the dairy farmers. As the operating environment of the Board became increasingly unsustainable, the government was forced to revise the incentives it was giving to farmers. This manifested itself in the adoption of a new pricing policy which led to the decline of producer prices. A number of related factors account for this phenomenon. The national economy, which had experienced considerable growth during the immediate post-Second World War years, began to slacken, with a consequent check to further expansion of dairy farming. From about 1957/1958, there was a marked drop in gross capital formation. This began with a decline in the price of copper in 1956 and 1957,66 and was accentuated by the international economic recession in 1958 which stretched well into the 1960s. In addition, the high rate of European immigration, which increased with the outbreak of the war, had begun to subside somewhat from the late 1950s, with the result that the market for dairy products, which was predominantly white at this stage, ceased to expand. To make matters worse, this was happening against the backdrop of increasing dairy production.

Despite the Board's early efforts to broaden the market for dairy products, particularly in the lucrative whole milk trade, the increased rate of production continued to outstrip the growth of the market. In this case, the official policy to stimulate milk production during the early 1950s, which was in fundamental accord with the general post-war economic climate when more people earning and consuming more had to be supplied with more dairy products, had begun to be exhausted by the late 1950s. It was in this context that steps were taken to curtail incentives aimed at increasing production, as well as the measures taken to increase the market for dairy products, especially whole milk. The campaign was particularly aimed at the burgeoning African population in the main centres. Most controversial and far-reaching, however, were the steps taken to reduce, or even eliminate, competition to the Board in the retail of whole milk.

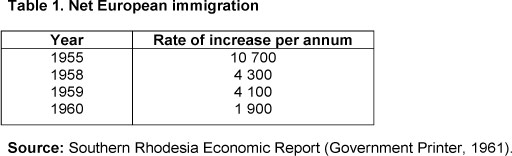

The root of the problems bedevilling the dairy industry from the late 1950s stemmed from increasing milk production on the dairy farms against a background of a market that was fast becoming saturated. By 1957, the production of milk was firmly on the ascendancy, with the Board receiving an average of an 8% increase per annum.67 Meanwhile, the rate of white population increase, on which the industry largely depended for the domestic market, was dropping. The African market, despite the early efforts to stimulate it, was still generally under utilised at this time. Table 1 below illustrates the decreasing rate of European immigration in the country.

The falling rate of European immigration, coupled with decreasing purchasing power caused by the drop in economic growth, had the effect of increasing the proportion of milk converted into low realisation products such as cheese and skimmed milk. The result of this was that the Board's profits, if ever they really existed, were decreasing with each passing year. This was so, largely because the prices that the DMB paid to producers were fixed by the government, after consultations with the RNFU. In fact, the DMB's financial position was becoming dangerously precarious as its net realisation from the processing and sale of milk products continued to fall. By 1958, for instance, the proportion of milk that was converted into less remunerative products was nearly 58%.The increasing losses that the Board continued to incur during the mid 1950s may partly be attributed to the plummeting net realisation it received from the sale of dairy products against a background of increasing payouts to farmers. The loss of a whopping £86 056 which the Board incurred during the 1956/1957 was attributed to the "suffocating financial situation in which the Board was obliged to pay producers increasingly high prices" without consideration of the income it was earning from the sale of the dairy products.68

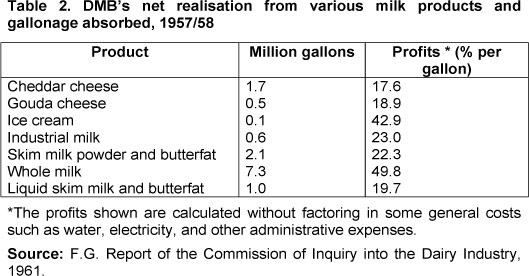

As already shown, the major problem associated with the conversion of surplus milk into skim milk (both liquid and powder), butter and especially cheese, was the low profit realisation of the products. In addition, although the price of liquid skim milk and "lacto" was increased in 1957 to economic levels, the profit accrued was a long way below the realisation from whole milk sales. Similarly, profits that could be made from the sale of skimmed milk powder were significantly lower when compared to whole milk sales. The proliferation of cheaper imported brands aggravated the problem. Table 2 below illustrates the Board's net realisation from various milk products in 1958.

From the above statistics it can be observed that the most profitable products were whole milk and ice cream. In fact, liquid milk sales generally offered better profit realisation than solid products such as cheese. A number of ways of increasing the sale of liquid milk (preferably as whole milk) were explored. As early as 1955, no doubt using the federal connection, efforts were made to find external markets for whole milk and sterilised milk in Northern Rhodesia. This initiative appeared viable at the time because there were milk shortages in the dairy industry in Northern Rhodesia, particularly on the Copper Belt where population densities were high and production of milk low.69 Experiments were successfully carried out in transporting milk from Salisbury to Lusaka with the results proving that the transportation could be done with minimal deterioration in the quality of milk. Within the year, Southern Rhodesia was exporting milk to Northern Rhodesia through the Co-operative Creameries of Northern Rhodesia (CCNR), a quasi-state enterprise through which the federal government regulated the dairy industry in that territory. For instance, in 1956 a total of 3 million gallons of whole milk was exported to Northern Rhodesia.70 However, this was not an assured market for Southern Rhodesia - her northern neighbour only accepted milk during the time of shortage and even then, it was only for a brief period of time. In his correspondence, O. Wadsworth, the chairperson of the CCNR intimated:

We would be grateful to accept milk from Southern Rhodesia, but with the understanding that this arrangement will be short lived. This is because we are making frantic efforts to increase local production, and within a few yearsNorthern Rhodesia should be self-supporting in milk.71

Indeed, whole milk exports to Northern Rhodesia ceased in November 1958 and the CCNR stopped all imports of whole milk. Later attempts to export sterilised milk to the same territory were unsuccessful. DMB proposals to the federal government regarding the manufacture of the product were rejected by the federal treasury because it "considered that the market for this type of milk should be proved before the necessary capital was committed, and that the Board should pay the full unsubsidised cost of all milk used in this scheme".72 This laid to rest all the hopes that Southern Rhodesia had of using the federal connection to solve her milk disposal problems prior to 1961, when the DMB took over the business of the CCNR. The DMB's ongoing problem of milk disposal could not, it seemed, be solved by selling its milk surplus to Southern Rhodesia's federal partners. This was so, particularly given the geographical and logistical problems that hindered the exportation of whole milk to Nyasaland, Southern Rhodesia's other federal partner, despite the relatively undeveloped nature of that territory's dairy industry. From the foregoing, one may argue that the existence of the federation did not play a crucial role in helping the Southern Rhodesia dairy industry during the 1950s. The existence of the CCNR in Northern Rhodesia which played a role largely similar to that of the DMB in Southern Rhodesia, proved to be the greatest disadvantage to the DMB in its effort to exploit the Northern Rhodesian market. The geographical location of Nyasaland, given the technology of the time, made the transportation of whole milk virtually impossible.

Following the failure to effectively exploit the federal market in the sale of whole milk, the Board explored the Portuguese East African market. Considering the relatively less sophisticated dairy industry in that territory at the time, it was felt that Portuguese East Africa could be used as an outlet to dispose surplus whole milk produced in Southern Rhodesia. An agreement between the two territories was reached at the beginning of 1956 for the exportation of whole milk to Portuguese East Africa, particularly Beira. Milk in pint bottles was sent out to Beira from the Umtali dairy on the evening train which arrived in Beira the following morning, and approximately 1500 gallons a day were sold to a DMB agent in Beira.73 Although part of the agreement between Portuguese East Africa and Southern Rhodesia, as with the one between Southern and Northern Rhodesia, provided that supplies "should not interfere with milk production in that territory",74 sales to Portuguese East Africa in fact continued to increase until the mid 1970s when the territory attained independence and ceased diplomatic relations with Rhodesia. The continued increase in sales to that territory was caused by the fact that the dairy industry there was not developed enough to cater sufficiently for all its dairy needs. What emerges from this scenario is that in the dairy industry, Portuguese East Africa became a far more useful trading partner to Southern Rhodesia than both Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland for much of the 1950s, and even beyond.

The impact of all the strenuous efforts to increase liquid milk sales both within and outside Southern Rhodesia from 1954 to 1956 was counteracted by the astronomical growth in milk production. As sales increased steadily, production levels were sky rocketing to the extent that the proportion of milk that needed to be converted into the less remunerative products like cheese and skimmed milk powder was constantly increasing. Given the slackened rate of growth of the national economy and apparent saturation of the market for whole milk, the incentives for stimulating production became increasingly difficult to sustain. By late 1956, the writing began to appear on the wall that the status quo could not be maintained indefinitely.

This scenario generated debate on whether it was still necessary to continue with incentives aimed at increasing production at a time when the bulk of the milk was converted into the much needed but less remunerative products such as cheese, butter and skimmed milk powder. The debate was made even more complex by the fact that although the colony had successfully managed to satisfy the demand for whole milk, seasonal shortages of cheese and butter had not yet been completely eradicated. In addition, a greater proportion of the skimmed milk powder that was consumed in the country at this time was imported.

Initially, the government's position, as was the case with general agricultural policy, was to push for self-sufficiency in all dairy products. This implied that the government still preferred to have increased production of milk so that more milk could be converted into cheese and other products so that it could eventually achieve self sufficiency. However, this policy was proving expensive for the dairy industry. Given the higher costs of manufacturing products other than whole milk, it was felt it would be better to think in terms of importing these products rather than manufacturing them at a considerable loss to the Board.75 T.C Pascoe argued that pursuing self-sufficiency in all dairy products under the current operating environment would be "financially ruinous to the Board".76 The logic of this argument stemmed from the fact that the other products could not yet be viably manufactured and hence increasing the proportion of milk converted into other products would ruin the economics of the Board's operation. Instead, it advocated the review of the pricing system so that the prices paid to the farmers would reflect the declining net realisation their milk fetched for the Board.

In support of the DMB's position, the Dairy Association criticised the policy of self-sufficiency, arguing that the Board should concentrate on those products which could help the industry survive. Writing to the RNFU, A. Harvey, the president of the Dairy Association noted:

In considering whether the aim should be complete self-sufficiency in dairy produce, the Association concludes that the Federation could not hope to produce economically every single dairy product. Self sufficiency would mean in effect [mean producing] surplus [for] export. In view of the conditions surrounding the production of dairy products here as compared with other exporting countries such as New Zealand and Australia, the Association recommends that self-sufficiency in all dairy products would not, in the present circumstances, be a proper aim for agricultural policy.77

The Dairy Association went further to suggest that first priority should be given to the processing of whole milk, and the exploration of opportunities for the export of the product, after which the second priority should be other liquid milk products such as sterilised milk and liquid skim milk to meet domestic needs. Taking third priority would be the manufacture of Cheddar and Gouda cheese, and this was because, in addition to the issue of low returns from their manufacture, the products had a significantly smaller domestic market.78 The view of the Board and the Dairy Association eventually won the day. The government giving in to their position. The colony continued to be a net exporter of whole milk while at the same time periodically importing cheese and butter from South Africa and Kenya until the late 1960s.

It was in this light that the DMB successfully lobbied for the introduction of a two-pool pricing system under which the first price would be paid for milk that would be utilised as whole milk and a separate, and lower price would then be paid for milk that would be utilised as industrial milk.79 In comparison with the quota system, both the government and the RNFU agreed that this pricing mechanism would help to stabilise the financial position of the Board while at the same time eliminating inefficient producers who had been solely dependent on high producer prices for their survival. Because the government was reeling from the effects of the economic recession, it could hardly afford to subsidise the farmers by maintaining the high producer prices. It is in this context that the eventual compromise between a market based system and a fixed price system should be located. Indeed, average producer prices paid for milk by 1964 had fallen to 32.20d from 37.50d per gallon in 1957.80

Despite the constantly declining producer prices, the intake of milk at the country's dairies continued to increase, albeit at a slower rate. In theory, of course, declining prices should have curbed increased production and bring price stability. In reality, this was not the case. On the contrary, the milk intake at all diaries continued to increase from year to year until the mid-1970s.This is with the exception of the 1958/59 year when the initial shock of price reductions led to a decreased output. A number of factors account for this phenomenon. Unlike other agricultural branches such as maize and tobacco farming, dairying is a long-term project which one cannot quit overnight once investments have been made. Instead of forsaking the industry, most farmers sought other survival strategies within the industry, including the earlier discussed cost-cutting measures and improving efficiency on the farms. The other factor was that, like farmers in other spheres of agriculture, dairy farmers sought to meet the challenge of declining prices by increasing yield. They countered the smaller profit margin by increasing the output of milk to maintain the substantial profit levels they had achieved during the era of high prices. This was particularly rife among dairymen who practiced mono-farming because of limited land holdings.81

In addition, the situation in other formerly more lucrative spheres of agriculture was equally, if not more, lugubrious. Farmers in the maize and tobacco sectors were facing a more serious profitability crisis during the late 1950s through to the 1960s. Maize producers were reeling under the yoke of the unprofitable export burden as the positive impact of the Second World War on the industry had begun to fade.82 This meant that, instead of switching away from dairying, there was instead an increase in the number of farmers venturing into dairying. It is in this light that the Commission of Inquiry into the dairy industry in 1961 reported that:

There is a possibility during the next year or two, with a decline in the maize price and with rising costs or lower prices in the tobacco industry, that dairying will become more profitable relative to those crops than it is at present and will be increasingly looked to by farmers.83

The net effect of this was the worsening of the situation regarding producer prices. As more milk was converted into products other than whole milk, the payout to producers from the net-realisation profit declined further. Crucially, the situation had dire financial consequences for the Board itself. From 1957 onwards, the DMB's financial position was becoming dangerously precarious as its net realisation from the processing and sale of milk by-products began to fall. In 1958, for instance, the proportion of milk that was converted into less remunerative products was nearly 58 percent of total milk received.84 The increasing losses that the Board continued to incur from the mid-1950s may partly be attributed to the plummeting net realisation it received from the sale of low profit by-products against a background of increasing payouts to farmers. For example, the significant loss of £86 056 which the Board incurred during the period 1956/1957 was attributed to the "suffocating financial situation in which the Board was obliged to pay producers increasingly high prices, without due consideration of the income it was earning from the sale of less remunerative products".85 It became increasingly clear that in addition to increased farm efficiency, the solution lay in the expansion of the whole milk market.

Expanding the market

The DMB was pushed to find additional outlets of whole milk both within and outside the territory by the increasing proportion of milk that was utilised for the manufacture of the less rewarding products such as cheese, skimmed milk powder, among others. Two unrelated factors, as earlier illustrated, connived to bring about this situation - the impact of increased milk production was aggravated by the decreasing rate of European immigration from the late 1950s. This forced the DMB to shift its attention to the African urban market. It is the contention of the author that more than any other reason, it was the need to increase the whole milk market in the face of the saturated and static European population that a vigorous drive was made to make urban Africans more milk conscious. To claim, as the Board often did, that the move was driven by a desire to improve the health of Africans is certainly to major on minor issues.

Virtually all investigations on the methods that could be used to increase whole milk sales pointed to the need to develop the African market as the long term solution to the Board's ongoing marketing problems. The Agricultural Marketing Council in 1958 stated that it considered "that the long term solution to the producer's cost price dilemma lies in increasing the proportion of milk on the whole milk market through an expansion of sales of liquid milk to the vast potential African consumer market".86 In the same vein, the 1959 Committee of Inquiry into the Dairy Industry noted that there was a "large potential market among Africans, which can be expected to consume more, both with changing patterns of urban life among Africans and incomes per head".87It went on to recommend that "every effort be made to increase the sale of milk to the urban African population".88

The 1961 Commission of Inquiry was more elaborative in its analysis of the pivotal role the urban African population was to play in the development of the dairy industry. It advocated the development of a strategy aimed at studying the culture and habits of Africans with a view to push them to become more ardent milk consumers. In no uncertain terms, it reported that:

In view of [Southern] Rhodesia's racial composition, and the prospect of the large African population doubling every twenty-five years and becoming urban dwellers even faster, it is incumbent on the dairy industry and the Government to develop the African market by all means conceivable. It is no use complaining, as occurred all too frequently in the course of our hearings, that the urban African develops a predilection for cold drinks and beer than for milk ... All producers of consumer goods, and its importers too, are vying hard for a share of the African dollar, and it will depend on the efficacy of the efforts of the Board on what share the dairy industry gets.89

There is no doubt that this statement gives further credence to the contention that more than just the earlier purported agenda of improving nutritional health of the African sector, the authorities sought to push for the involvement of Africans in the industry as consumers so that they could increase their "share of the African dollar".

A battery of measures was taken to increase whole milk sales to the African urban dweller. The erection of numerous DMB depots in African townships should be viewed in this light. The first milk depot to commence operations was in the Harari [renamed Mbare in 1980 when Salisbury was renamed Harare] township of Salisbury in 1958, and another was built in Gatooma later in the same year.90 In explaining the rationale behind the establishment of depots, the Board stated:

As whole milk utilisation is on the decline, further efforts will be made to increase sales, especially to the African population. With this end in view, the Board has made representations to most of the municipalities for permission to operate fixed depots in African locations from which milk, skim milk and other dairy products can be sold.91

The number of depots in African townships increased so much that by 1980, on the eve of independence, the Board had a depot in more than half of the country's African townships.

In addition, the Board began to employ more Africans in the major towns as "delivery boys". These people would move around in most African locations on tricycles, marketing dairy products to the people. Indeed, the Board reported in 1976 that the huge expenditure in the early 1960s on the recruitment of African salesmen had begun to pay dividends as "sales in African areas have been growing and, in the process, compensating for the reduced sales in European areas".92 In order to increase the sales by the salesmen, two means were used to entice consumers to purchase milk.

Beginning in July 1962, a new pricing system was adopted after gaining the approval of the government. Under this system the cash price for milk was fixed at an inflated price of 8.25d per pint. In addition a new price of 5/3d per gallon for milk purchases in excess of three gallons at one time was adopted.93 Also, the use of tokens, as an alternative to cash payments, was introduced in 1961.Under this system, consumers could purchase packets of tokens which they could use to pay for milk. The advantages which were claimed in respect of this system were that "it speeds up deliveries and consumer satisfaction is increased".94 By the late 1960s, this method of payment had increased in popularity. However, its popularity was especially noticeable among the European consumers; Africans seldom bought the tokens because they preferred to buy milk for immediate use. In fact, this situation led many DMB officials to develop the attitude that Africans were mean and had not yet learned the basics of budgeting and savings.95 One producer suggested that Africans "should be taught to desist from the habit of overspending on immediate pleasures".96 What the authorities, and indeed, the rest of the white community chose to ignore were the relatively more difficult economic circumstances that African workers faced as a result of the wide gap that existed between black and white income levels.

In another attempt to increase the outlet of whole milk, in 1957 the board introduced a scheme of supplying school children with one-third pint bottles of milk in Salisbury. Under this scheme, fresh milk was sold to primary school children in close collaboration with school authorities.97 To increase the popularity of this scheme the DMB in 1961 decided to introduce a monthly prize of £10 to the funds of the school which sold the most milk in relation to pupils on the attendance register.98 This became a permanent scene in most African schools in Salisbury throughout the colonial period with the result that an average of 520 000 gallons of milk were utilised for this purpose between 1964 and 1974.99 It is worth nothing that this arrangement, which was adopted from England where pupils were given free milk at the expense of the government,100 was justified in Southern Rhodesia on the grounds that it would "inculcate in young Africans the desire for milk at an early age".101 While in England it was aimed at improving the health of children, particularly those with a disadvantaged background, since milk is known to "show an increase of 20% in height and weight in children between 5 and 15 years of age regularly taking it over those without access to it,102 in Southern Rhodesia the underlying principle was increasing the market. This plan to inculcate milk consuming habits in Africans from a tender age should be viewed within the general opinion that African men seemed to have a predilection towards alcohol and soft drinks.

So determined were the Board's efforts to increase the consumption of dairy products, particularly whole milk, that a series of advertisements and campaigns were launched. These were done through the medium of the press and cinema advertisements "with the object of impressing upon the consumer, particularly the African, the value of milk and milk products in the daily diet".103 In addition, efforts were also made to increase the sale of whole milk together with acidulated lactic milk (lacto) which had become increasingly popular among Africans, through the employment of African demonstrators and dieticians who moved around African institutions "educating" Africans on the importance of milk and other dairy products to their general health. In May, 1958, a sales promotion officer was appointed, and was followed shortly afterwards by the appointment of a female dietician whose main duty was to hold a series of lectures and demonstrations at African institutions.104 These campaigns contributed significantly to improving the sales of dairy products among Africans. In 1965, H. Wulfsohn, the acting chairman of the DMB, could reflect on the success of the programme with satisfaction and say "... these efforts, together with requests for the Board to extend its activities by entering certain other towns, have resulted in substantial sales increases over the past six years".105 Indeed, sales of whole milk in African townships increased from an average of 92 000 gallons in 1959/1960 to 352 000 gallons in 1964/1965.106

In addition to increasing the number of depots in African townships as well as the number of salesmen making door-to-door deliveries in African areas, in 1967 the Board introduced a new milk booklet entitled Milk is Best which was liberally illustrated with photographs showing Africans at work and children at play enjoying a glass of milk.107 This booklet, which was conveniently printed in the indigenous Shona and SiNdebele languages, was distributed through social welfare organisations and by advertisements in popular magazines.108 In a further effort to reach out to the African market, an extensive advertising campaign through the radio, cinema and print media was introduced in 1969. Slogans such as "Milk Turns Men into Tigers!" became a popular jingle in most DMB advertisements. Particularly interesting was one advert which appeared on DMB motor vans during the late 1960s with a picture of a cheerful tiger holding up a glass of milk. Underneath this picture was a caption which read: "This is a glass of Tiger Juice, some people still call it milk. Buy it from the DMB!"109

Besides targeting the burgeoning urban African population, the Board also engaged private enterprises for the purposes of increasing its sales of whole milk. In 1960, the government commenced negotiations with Nestlé (Pty) Ltd for the construction of a milk plant in Salisbury that would manufacture skimmed milk powder, condensed milk and baby milk products. The company began operations in 1961. As a matter of policy, the company was forbidden from buying its milk from producers or any other source besides the DMB.110 This arrangement worked to the benefit of the Board in one important way - although the manufacture of skimmed milk provider by a private concern increased competition for the Board's own products, the arrangement assured the Board of a market for the more remunerative whole milk. In any case, as an internationally reputable company with vast experience in dairy production, Nestlé had a better capacity to produce manufactured dairy products at a profit than the Board. Indeed, the company continued to take increasing quantities of milk from the Board for the purposes of manufacturing full cream milk powder and proprietary baby foods for both local and export markets. For instance, the volume of milk supplied to Nestlé during 1964/1965 was 2 682 000 gallons, representing approximately 16 percent of the Board's total milk intake.111

The government granted an operating licence to Lyons Ltd in 1962 for much the same reason that it allowed Nestlé to operate. However, the Board was initially inclined to cavil at this decision because, unlike full cream and skimmed milk powder which Nestlé produced, the Board had always obtained a high price return from the manufacture of ice cream. Hence, it felt that Lyons, as a company that had attained considerable international status and had more technical resources, would effectively out-compete and push the Board out of the ice cream business.112 However, considering that a very small amount of milk is utilised in ice cream manufacture and that whole milk sales always fetched higher returns, the Board eventually changed its position. In any event, Lyons drew its supplies from the DMB as a matter of policy.

Perhaps one of the most important moves taken by the Board during the 1960s in its attempt to expand the market for its products was the takeover of Northern Rhodesia's CCNR in 1962. The DMB was responsible only for the regulation of the dairy industry in Southern Rhodesia, despite the existence of the Central African Federation. The CCNR acted as a government agency, and was the medium through which the industry was regulated in Northern Rhodesia, the industry was so undeveloped in Nyasaland that no regulatory body was needed.113 What proved to be to the DMB's disadvantage with regard to the Nyasaland market were the geographical challenges involved in the transportation of whole milk. This arrangement, as shown earlier, was largely responsible for the fact that Southern Rhodesia could not penetrate her federal partners' markets in any significant way. In any case, she was struggling to satisfy her own local needs when the federation was instituted. As the need for markets increased, the Board, through the Federal Ministry of Agriculture, lobbied for the creation of one single regulatory authority for both Southern Rhodesia and Northern Rhodesia. In fact, as the writing began to appear on the wall that the local market was fast becoming saturated, the 1959 Committee of Inquiry reported that:

The Committee considers that it is desirable to have overall marketing control in the Federation in the hands of one Federal marketing organisation, and recommends accordingly. The existing co-operative in Northern Rhodesia could become an agent of this overall authority.114

Given the relatively greater political clout of Southern Rhodesia and her white settlers in comparison with the northern federal territories, and the increasingly dire circumstances in which their dairy industry was operated, the lobby was met with little resistance from the federal government. To this end, negotiations for the takeover of the CCNR's operations between the federal government and the CCNR commenced in mid-1961, with the result that the DMB officially took over the Northern Rhodesian dairy industry in July 1962, on an initial caretaker basis pending finalisation of the Creameries' accounts and completion of other formalities.115 The most important impact of this takeover was that Southern Rhodesia began to consider her northern neighbour as part of the "domestic" market. Within the eighteen months that this arrangement lasted, vast quantities of whole milk and sterilised milk were transported to Northern Rhodesia, particularly the Copperbelt region where a ready market existed. Approximately 5 500 000 gallons of milk, a modest 1 000 lb of butter, and 1 850 lb of Cheddar and Gouda cheese were disposed of in that territory as the DMB took charge of all the twelve dairies that the CCNR had operated in Northern Rhodesia.116 However, and unfortunately for the DMB, this arrangement was short lived: it broke down together with the dissolution of the federation in 1963, and the Board was forced to cease its operations in that territory.

Elimination of producer retailers