Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Historia

On-line version ISSN 2309-8392

Print version ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.58 n.1 Durban Jan. 2013

ARTICLES ARTIKELS

Changing attitudes of South Africans towards Italy and its people during the Second World War, 1939 to 1945

Anri Delport

Currently enrolled at the University of Stellenbosch for a MA which deals with the social conditions, resulting ailments, rehabilitation and aid received by South African soldiers during the First World War. This article is based on a previous research project supervised by Prof. Bill Nasson

ABSTRACT

The emphasis of this article falls on South African wartime attitudes towards Italy structured around the differentiation in attitudes between the Union government; the domestic sphere; and the armed forces. On 11 June 1940 the Union issued a declaration of war in response to Italy's new belligerent status. Attitudes towards Italy were thus altered from "unofficial" to being an "official" enemy of the Union. Less than a month later, Union soldiers embarked on their first campaign in East Africa and later North Africa. In early 1942 the fighting moved across the Mediterranean to Italy. On 8 September 1943, Italy surrendered to the Allies thus shifting Italy's domestic position from enemy to liberator. Thereafter, South Africans fought alongside anti-fascist Italian partisans against German occupation thus altering their relationship to comrades. Although the war ended on 8 May 1945, many Italian POWs interned in South Africa still awaited repatriation. Some remained in the country or returned and made South Africa their new place of residence, taking advantage of South Africa's acceptance of Italian nationals. Similarly, some South Africans formerly held in European POW camps took Italian wives and adopted a new culture as a consequence of the war. This article illustrates the changing South African attitudes towards Italy during the different phases of the war as well as the variation in attitudes between different factions in South African society.

Keywords: South Africa; Italy; World War II; war attitudes; Italian forces; Italian Immigrants; Italian nationals; prisoners of war; Fascist Italy; Ossewabrandwag; Zonderwater; Italian internment camps

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel beklemtoon die algemene Suid-Afrikaanse oorlogsgesindheid teenoor Italië, gegrond op die verskille in gesindhede onder die Unie regering, die algemene bevolking en die gewapende magte. Op 11 Junie 1940 het die Unie 'n verklaring van oorlog uitgereik in reaksie op die fascistiese staat se nuwe hardkoppige houding. Die verhouding met Italië het dus verander van 'n "nie-amptelike" na "amptelike" vyand van die Unie. Minder as 'n maand later vertrek die Unie se soldate op hul eerste veldtog in Oos-Afrika en later Noord-Afrika, as deel van die Geallieerders. Die gevegte het vroeg in 1942 tot oorkant die Mediterreense See geskuif na Italië. Die Italianers het op 8 September 1943 oorgegee aan die Geallieerdes en dus het die Italianers se status in Italië verander van vyand tot bevryder. Daarna het Suid-Afrikaners saam met anti-fascistiese Italiaanse partisane geveg teen Duitse besetting, en is hul toe gesien as kamerade. Alhoewel die oorlog op 8 Mei 1945 geëindig het, het baie Italiaanse krysgevangenes wat geïnterneer is na Suid-Afrika, steeds gewag op repatriasie. Sommige het hier gebly en ander het selfs teruggekom en Suid-Afrika hulle nuwe woonplek gemaak, wat dui op die feit dat Italianers plaaslik aanvaar is as deel van die bevolking. Soortgelyk het sommige Suid-Afrikaners wat voorheen in Europese gevangeniskampe aangehou was, Italiaanse vroue geneem en 'n nuwe kultuur aangeneem as 'n gevolg van die oorlog. Hierdie artikel illustreer die verandering van Suid-Afrikaanse gesindhede teenoor Italië gedurende die verskillende fases van die oorlog, asook die verskil onder verskillende faksies van die Unie.

Sleutelwoorde: Suid-Afrika; Italië; Tweede Wêreld Oorlog; orlogsgesindheid; Italiaanse magte; Italiaanse immigrante, Italiaanse burgers; krygsgevangenes; Fascistiese Italië; Ossewabrandwag; Zonderwater; interneringskampe

Introduction

Internationally, research on World War Two (WWII) focuses on the actions and involvement of the major European states; this results in the overemphasis of certain themes and the severe neglect of others. One such neglected theme is the views held by different nationalities that formed part of the Axis force, such as Italy, and members of the British Commonwealth, such as South Africa. This paper investigates a particular dimension of South Africa's involvement in WWII and its relationship with Italy. It concentrates on the wartime attitudes of various South African factions, exploring their political, domestic and military perceptions towards Italy, an Axis power.

General shifts in attitude are identified which effectively divide the war period into phases; these will be explored chronologically in this article. Firstly, attitudes which clustered around the notion of Italy as the "unofficial" enemy are discussed by considering the division that existed in the Union on the issue of war participation. The next shift in attitude came with South African participation in the North and East African campaigns and the experiences of prisoners of war (POWs) in Italian camps. Thus, the focus falls on Italy as the "official" enemy of the Union of South Africa. The Allied liberation of Italy led to another shift of South African sentiments - one of brothers-in-arms as Italian resistance forces fought alongside South African troops. This was followed by a final modification in the aftermath of the war as reflected in immigration policy and statistics in Union censuses.

In order to analyse these attitudes, the focus falls on war memoirs and diaries kept by South African soldiers who fought abroad. This, however, does not provide a broad enough sample to capture all attitudes; the task of throwing a wide enough net to capture all wartime sentiments would be impossible, so findings are based on a limited sample. More importantly, the available sources from white soldiers restrict findings to white opinion only. In an attempt to circumvent this challenge, published cartoons, newspaper articles and archival sources are also used. Furthermore, use has been made of Pietro Corgatelli's unpublished Master's dissertation documenting the local history of Italians in the Western Cape in the first half of the twentieth century. This source proved particularly useful because it is based primarily on oral testimonies and includes transcribed interviews. Since the focus of this research essay falls on war-attitudes, it was necessary to place them in context. For instance, to interpret the feelings invoked by a cartoon or personal account, the publication date as well as the explicit message it conveys, are important, so secondary sources were also used.

The 'unofficial' enemy (6 September 1939-10 June 1940)

On 3 September 1939, Britain declared war on Germany. One day thereafter, the Drill Hall of the Active Citizen's Force (ACF) in Johannesburg seethed with activity, despite the fact that neither mobilisation orders nor orders permitting the ACF to accept volunteers had been issued. One such volunteer was an officer from the Transvaal Scottish, a colourful, flamboyant, one-armed, commercial artist, Eric "Scrubbs" Ponsoby Hartshorn. The eagerness of volunteers is described by Hartshorn:

Some [are] from ... Rhodesia. Women drivers voluntarily filled up their cars with eager young men anxious to get to the Drill Hall with the least possible delay. Some even arrived by bicycle. All were actuated by one motive. To get cracking.1

In Worcester on 6 September 1939, while the public waited with great anticipation to hear the Union's official position on the war, a spry 106-year- old, Kaas Willemse, was charged with being drunk. When appearing before the magistrate Willemse was asked the reasons for his disorderly conduct. He replied that he was celebrating the war.2 Such sentiments were common for the the pro-war section of the Union as other sources indicate, yet this "nation" comprised only the ruling white minority.

In contrast, another faction of that "European" community, most notably the Ossewabrandwag and its supporters, were opposed to the war. Some members, mostly young Afrikaners from the Transvaal, wore brown or grey shirts with swastika armbands. They had the same anti-Jewish sentiments as the Nazis and their meetings turned into riots, usually involving quart bottles of beer. As the young men became more intoxicated they talked in a derogatory fashion against the Jews. The rowdy men asked the crowd: "Where do you think your daughters are tonight? They're sleeping with Jews in the back of their cars."3 This was part of the general mood.

The overwhelming majority of "non-white"4 South Africans had little concern for the war - it was considered a far distant white man's war.5During a campaign to encourage support for the war effort, the following question was raised at a meeting by a speaker in New Brighton, a black township in the Eastern Cape:

Why should we fight for you? We fought for you in the Boer War and you betrayed us to the Dutch. We fought for you in [the] last war. We died in France, in East Africa ... and when it was over, did anyone care about us? What have we to fight for?6

In December 1939 a resolution was passed at the annual gathering of the African National Congress (ANC); it stipulated that the ANC would only advise Africans to participate in the war if they were granted "full democratic and citizen rights", although this position was later modified.7

Meanwhile, foreign citizens of the Axis powers residing in the Union had their own problems. Some German nationals were recalled to the Third Reich, others faced internment, ordered by the Union government, as enemy aliens.8 On 14 June 1939, the Aliens Registration Act (No. 26 of 1939) was passed which required under Section 11 that employers had to document the particulars of aliens in their employ, including both Italians and Germans.9 These individuals were to be suspended on full salary pending a decision on their future treatment during wartime.

In archival collections there is confidential correspondence to this effect between employers (such as Cape Explosive Works Ltd. and De Beers), local magistrates and the Department of Justice. Emergency measures are laid down to be followed in the eventuality of Italy entering the war. Furthermore the Department of Justice wished to be kept appraised by employers of any "suspicious" behaviour on the part of alien employees regardless of whether they were enemy reservists or nationals. Some correspondence indicates the employers' willingness to assist authorities to have Italian employees interned in the case of the outbreak of hostilities.10 Many members of the Italian community who resided in South Africa found themselves in an awkward position due to Rome's alliance with Berlin.11 The offices of the Department of the Interior were overwhelmed by Italian inhabitants desperately applying for South African citizenship.12 Despite Italy's declaration of non-belligerence at the time of the outbreak of the war, many Italians in the Union lived in a period of uncertainty, anxiety and restless suspicion.13

The schism within the white minority of the Union was reflected in the coalition government. The post-1934 coalition and then fusion of the South African Party and National Party to form the United Party was led by two generals: a prime minister in James Barry Munnik Hertzog and a deputy prime minister in the person of Jan Christiaan Smuts. In 1931 the Statute of Westminster had confirmed the Union's legal autonomy; the Union's sovereign parliament could decide on its own domestic and foreign policy.14

At a special sitting of parliament on 4 September, the day after Britain's declared war, the Union's position on the war was placed discussed. Hertzog passed a motion of neutrality. According to him, the situation that Britain and France found themselves in was of their own making, namely the Versailles Diktat. In this speech, Hertzog empathised with Germany because in his view Britain had placed itself in the same position as the republican Afrikaners had done in 1902 with the Treaty of Vereeniging. Furthermore, the failure to pass this motion (of neutrality in the war), he said, would be at the cost of South African unity; it would divide the white Afrikaner and English-speaking communities.15 However, Smuts argued that it would be in the Union's interest to align itself with the British Commonwealth, because soon Hitler's Lebensraum policy would include South West Africa and the Union thereafter. Moreover, Smuts gave a calculated political assurance that the government would not "send forces overseas as in the last war".16 The result of the sitting was the passing of Smuts's amendment by 80 votes to 67.17 On 5 September a Cape Times banner headline proclaimed, "General Smuts became Prime Minister today"; this was followed by the announcement of General Hertzog's resignation.18 The country was divided into different camps on the issue of involvement in the war, but despite these fractured domestic sentiments, the Union declared war on Germany.19 This division existed not only in the political, but also in the domestic sphere for the remainder of the war.

To better understand government sentiments towards Italy at this time, the formation of alliances in Europe needs to be considered. On 6 November 1937, Rome had joined the Anti-Comintern Pact, which had bound together Berlin and Tokyo since 25 November 1936. The intended goal of the alliance was to counter the subversive activity allegedly organised all over the world from Moscow by the Comintern,20 and Italian isolation as a consequence of its much-criticised ventures in Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) and Spain.

The Axis alliance allowed Italy to withstand any possible hostile coalitions in case of war. Still, it took two and a half years of bargaining to convert the Axis relationship into a military alliance. The Italo-German rapprochement culminated in the signing of the Pact of Steel on 22 May 1939.21 Consequently the alliance between the three Axis powers was cemented and translated into a common association of the Third Reich and Japan, namely the enemy, with Italy. Cartoons, such as Figure 1, often appeared in newspapers with caricatures of Mussolini and Hitler together. 22

The alliances of Europe seemed to guarantee a general war for which Italy was ill-prepared, because both the Italian Army and Air Force were in an antiquated state. After Rome's invasion of Abyssinia in October 1935 and Albania in April 1939, Mussolini announced that Italy was not prepared for war;23 Italy only physically participated in WWII from 1940. The period before this date was spent, much as in the Union, in preparing for war. Consequently, albeit that Italy did not issue a declaration of war until 1940, it was still considered to be Nazi Germany's less organised fascist cousin.

In December 1934, the Wal Wal incident resulted in the deaths of 200 Italians and Abyssinians and more importantly gave Italy a pretext for invasion. Ethiopia had escaped the European "scramble for Africa", but was dangerously situated between two Italian colonies, Eritrea and Somalia. The Italian fort at Wal Wal, an oasis in the Ogaden Province was built in 1930 and formed part of a gradual Italian encroachment into Ethiopian territory.

The "'incident" refers to a clash between this Italian force and a group of Ethiopians who formed part of an Anglo-Ethiopian boundary commission. It ended with an Italian ultimatum which would have required Ethiopian recognition of Italian sovereignty over Wal Wal. After the incident, the emperor of Abyssinia, Haile Selassie, appealed to the League of Nations for arbitration and both parties were exonerated.24

In response to the incident that triggered the Abyssinian crisis, the general staff of the Union Defence Force asked for money to assemble a force in opposition to Italian aggression in Africa. The classic response was, "who do you intend to fight?" At the time, South Africa was in the throes of the Great Depression. The general mood was isolationist; the white minority was divided between English and Afrikaners; and military planning was directed towards an envisaged bush war for securing the Union's borders. Since no immediate threat existed, the state's arms and training were largely of World War One vintage. The reaction of the Union government to the Second Italo-Abyssinian War was similar to that of the Abyssinian crisis. Some in government, such as Hertzog, did not support the Union's detached position. As he commented in 1936, "I do not see how the southern part of Africa can stand aside".25 In contrast, amongst the general citizenry, there was widespread criticism of Italian aggression, with leftwing trade unions and the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) calling for a boycott of Italy. As a result, union members working at the Cape Town docks refused to handle Italian ships.26

On the eve of war, the Union looked to its manpower, weapons and coastal defences and came to the realisation that these were sadly lacking. The Union was wholly unprepared despite Smuts's appeals for the security of an armed peace and the warning signs evident in Europe and Abyssinia. 27 Despite the unreadiness of the Union, deliberation unfolded after the declaration of war on where to send the South African military force once it was assembled. Smuts was now not only the new premier, but also Minister of Defence and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Hertzog's words were still remembered in 1939, all had knowledge of Italy's allegiance to Germany and few had doubts that Italy would soon be an "official" enemy. The two states were united under the Axis banner after the signing of the Pact of Steel. Consequently, the Union's position changed - its first responsibility was to guard the sea route around the Cape and to create an army and air force that would be able to:

...defend the desert outposts from the Indian Ocean to Lake Rudolf, its task to contain the Italians in Abyssinia. The air force would be used to harm them, destroy their pockets of planes, ammunition and fuel - which could never be replaced."28

An army and air force had to be built because the country's defence force spending was reduced at the time of Italian aggression in the 1930s to approximately £1million annually. During this time Italy was pouring modern weapons into Africa at an alarming rate, with its larger bomber aircraft, such as the Cant Z 1007b, having a range of 1 650 miles. Hypothetically, this would have allowed the Italians to bomb the Witwatersrand from Madagascar, the Belgian Congo, Tanganyika, Mozambique or Angola. The South African Air Force would have been incapable of halting such an assault.29

In the next months, the Union was occupied with preparing for war with its "unofficial" enemy, Italy now in East Africa. These preparations for the eventuality of war in East Africa revealed the Union's attitude towards Italy, perhaps more specifically government war-attitudes towards Italy than that of the citizenry. It is unclear to what extent those South Africans who supported participation in the war, supported it because of genuine animosity towards Fascist Italy; or whether their enmity was directed rather towards Nazi Germany; or whether they were swept up by unfocused war enthusiasm.

The 'official' enemy (11 June 1940-3 September 1943)

"An hour marked by destiny is striking in the sky of our country ... people of Italy to arms! Show you courage, your tenacity and your worth!" these words orated by Il Duce and directed to a cheering crowd of Fascists and Blackshirts, reverberated across the Piazza Venezia.30 On 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on France and Britain, thereby formally including Rome in the war, and demarcating the Italian state as an enemy of the Allies. In response, South Africa declared war on Italy the next day. The months of preparation had not been in vain for Italy was now an "official" enemy of the Union.

It was only in the mid-1920s that the influence of the new fascist regime, established in 1922, had an effect on Italian inhabitants living abroad. The distance from the Italian homeland, both in geographical and psychological terms, had reduced Italian dependence on their motherland.31 By the late 1930s, approximately 70 percent of Italian inhabitants had been residing in the Union for over ten years; 3 000 of them had taken South African citizenship and about 300 were Italian nationals.32 For many Italian residents changes made under the fascist regime were of marginal interest; memories that remained of their birth-country were associated with poverty, hunger and humiliation. Other Italian residents were estranged from Italy because the country was often represented by consuls who were detached from the emigrants' needs.33

One of the significant organisations arranged by the new Fascist regime was the Fasci Italiani all'Estereo.34 The aim of this organisation was outlined in eight principles, all concerned with providing a meeting place for Italian emigrants and to create awareness of new government initiatives. By the late 1920s a minimum of six Fasci, together with their respective ancillary organisations existed in major cities including Johannesburg, Cape Town, Pretoria, Durban, Port Elizabeth and East London.35 One of the initiatives undertaken by the organisation was sending Italian children to "see the land of their fathers ... free, without paying for anything".36 Furthermore an Italian School with between 50 and 100 students in Cape Town was also run by the Fasciti Movement. However, many of these children knew little of the Italian culture, what they knew was from their parents or the Fascist Youth Movement. Some Italian inhabitants, such as the father of an Italian resident, Antonio Introna, were "great admirer[s] of Benito Mussolini".37 Consequently, when Italy entered the war, the Italian community in the Union included some supporters of Fascist Italy. Yet other Italian inhabitants were assimilated into the South African population to the extent that they had little time for the sturdy Il Duce and his fascist ideals.

Notwithstanding this division in the Union's Italian community, when Italy formally aligned itself with the Third Reich, many Italian inhabitants were regarded with suspicion. In this period, not only government attitudes towards Italy, but also domestic attitudes changed. 38

The Union government reacted to this change in foreign relations by erecting internment camps for Italian and German inhabitants in 1939.39 Approximately 1 000 Italians who were resident in the Union, along with the crew of the Italian ships Timavo (beached by coastal defences north of St Mary's Hill) and Sistina (docked at Cape Town harbour), were placed in one of six internment camps, the most infamous of which was Zonderwater near Koffiefontein in the western Orange Free State.40 Italian residents, including Catholic priests, minors and South African citizens, were rounded up on the same day as Italy's declaration of belligerence. However, few were kept in these internment camps for the duration of the war.41 Most Italian civilians were allowed to leave, some applied for release on personal grounds, while the employers of others requested the release of their workers because their skills were required.42 The only Italians who remained in these camps were those who were active in the Fascist Party or did not press for their release on patriotic grounds.43

In addition, all assets belonging to both public and private Italian bodies were frozen. These actions had been planned months in advance for the eventuality of war by the Smuts government in association with sections of South African society which opposed Italian military power. In addition an anti-fascist campaign had been launched through the English press, warning the general population of the existence of an alleged "fifth column" lurking in the Union. 44 The government also revised its policy with regard to internments and pro-enemy subjects generally as a result of events overseas and the activities of members of the fifth column. Government was aware that there was a feeling of insecurity among the public and thus granted police permission to "quietly ... spy out the land and to consider what the danger [was] in their respective areas".45 As a result, members of the Italian community not interned were interrogated and harassed by the police. 46

Initially, and until late 1940, the British War Office only concerned itself with the shipment of German POWs overseas. However, such calculations proved to be too limited as campaigns commenced in North Africa. In early 1941, General Sir Archibald Wavell, commander-in-chief in the Middle East, reported to the War Office that over 59 000 Italians and 14 000 Libyan (colonial) troops had been taken captive. This report also expressed Wavell's concerns that he lacked the resources to guard, feed and administer such a large number of prisoners and even with resources, the POWs presented a threat to internal political stability in Egypt. To alleviate the situation Wavell had already begun shipping Italian officers to India, but this proved insufficient and thus Wavell requested a War Cabinet sanction to ship POWs to Kenya and South Africa as well.47

After the first South African victories in Italian East Africa in 1941, the first 10 000 Italian POWs arrived and were placed in a camp consisting of a few rough enclosures of barbed wire and conical tents. This POW camp at Zonderwater was developed over subsequent years as prisoner numbers rose, so that in 1943 there were 63 000 POWs. This camp was the biggest Allied war prisoner camp by the end of the war.48

Some South Africans who supported the war and opposed Germany, perceived Italians with some trepidation and hostility. Other elements of society, such as anti-British elements, indicated some private manifestations of sympathy towards Italian residents and later POWs. In other cases, propaganda against Italians was rejected because the community at large had never caused any problems and included colleagues, acquaintances or friends.49

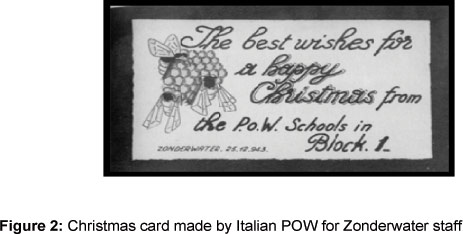

In later months, these attitudes were expressed in actions. For example, some South Africans and organised Afrikaner groups such as the Ossewabrandwag helped Italian POWs escape from camps and hid them. In other cases, aid was given to families of political detainees because they were often the breadwinners, and their families were destitute.50 There were also Italians who found themselves without employment and without friends; they were shown respect by other civilians when they were released from internment. However, fraternisation could bring consequences. When a South African soldier In Koffiefontein showed sympathy or kindness towards an Italian internee he was immediately replaced, for example in the case of Major Donkin. Christmas cards (see Figure 2), made by Italian POWs were sent to officers and staff of the camp.51 This gives the impression that by late 1943 some level of friendship had developed between Italian POWs and South Africans posted there. It seems that domestic attitudes towards Italian residents wavered between hostility and sympathy. The government's attitude, however, was explicit: the Italians were the enemy.52

In this period of the war, sentiment similar to that expressed by the Union government was pictured in the media. The cartoon (Figure 3) not only indicates the bafflement of the two fascist dictators over the failure of the Axis plan to bring resounding victory, but also depicts Mussolini as representative of Italy, with Hitler - as was common earlier in the war.53 However, not all cartoons linked Hitler and Mussolini. Others painted Mussolini, and thus Italy, in a negative light.54 For instance Figure 4 portrays Mussolini as cowardly and fearful.

When Italy entered the war, it occupied Libya in the north and Eritrea, Italian Somaliland and Abyssinia to the southeast.55 By August 1940, there were over 92 000 Italian and 250 000 Abyssinian troops in East Africa.56 By this time the Union had formed three divisions, namely the 1st South African Division consisting of the 1st, 2nd and 5th Brigades led by Major-General G.E. Brink; the 2nd South African Division consisting of the 3rd, 4th and 6th Brigades under the leadership of Major-General I.P. de Villiers; and lastly the 3rd South African Division comprising the reserve brigades for domestic defence led by Major-General H.N.W. Botha.57

The three battles in Africa that form a significant part of South African wartime history are: the defeat at Sidi Rezegh; the capture of Tobruk; and the battle that turned the tide - El Alamein.58 The first South African air and ground forces approximately 20 000 strong arrived in Kenya in May 1940 which included the 1st SA Brigade.59 In December the rest of the 1st South African Division joined these forces and until April 1941, the division, along with a contingent of the South African Air Force (SAAF), participated in operations in East Africa.60 The SAAF operated mostly in North Africa, thereafter in conjunction with the Royal Air Force (RAF).61

In late 1940, some friction arose between South African and British defence forces or more specifically, between Lieutenant-General D.P. Dickinson, the British officer commanding the East African Force, and Brigadier Dan Pienaar. Smuts arrived at force headquarters in Nairobi where he confronted Dickinson. The confrontation ended with Smuts who, bristling with anger, shouted: "I did not send my young men to die of fever in East Africa. I sent them here to drive the enemy out of Africa."62 These sentiments were shared by Cyril Crompton, initially of Bluff Command, who was relocated to the 1st South African Anti-Aircraft Regiment, 3rd Battery. In Crompton's memoir he notes: "The ultimate objective was to free Emperor Hailie Selassie, who had been captured and held captive in Addis Ababa, and his country subjugated by Italians."63 Evidently there was little confusion as to why Union soldiers were dispatched to North and East Africa and who the enemy was.

During actual fighting, little reference is made to Germans, or "jerries", and Italians, or "eyeties", beyond their movements. Most diary entries and memoirs of the time describe the harsh living conditions, lack of provisions and the heat by day and cold at night. Other entries describe scenes of slaughter and the emotions of horror and awe at how courageous soldiers died - both enemies and comrades. This contrasts with diaries written by soldiers who were captured by the enemy. It is only in these passages that any real mention is made of the Italians. Perhaps this can be attributed to South Africans not really considering the Italians as more than "the enemy", a fact that did not require any reiteration. Alternatively, it could be that South Africans never really came into contact with Italians directly; they were only observed on the battlefield and then only appeared as a target. It was only as POWs that South Africans really came into direct contact with Italians.

On 21 June 1942 at Tobruk, General Klopper surrendered 25 000 Allied soldiers64 to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. All of these men, including 10 722 South Africans of the 4th and 6th South African Brigades, were taken prisoner.65 Consequently, South African forces suffered the loss of nearly an entire division, with only 240 soldiers of four battalions,66 escaping capture.67 This event in particular, fostered attitudes of revanchism against the Axis powers, including Italy.

A South African policeman, George Stegmann who was captured at Tobruk, describes being en route to a POW camp in Benghazi in Libya:

Thousands upon thousands of German troop carriers passed us; the soldiers looked straight ahead, as if out of consideration of our feelings ...This was in direct contrast to the Italian soldiers who were continually swearing and jeering at us ... even spat on us ... a big Italian ... spat in my face and swore at me. When I wiped it off, he slapped me right across the face with the back of his hand. It was a bitter pill to swallow and I again felt hatred building up inside of me.68

This passage clearly illustrates the dejected soldier's attitude towards the Italians - there is no doubt he regards them as the enemy. Animosity toward this Axis power now seems more explicit than against the Germans. This sentiment is corroborated by another soldier, Ike Rosmarin, who explains that many prisoners admired the Germans for their organisation, but had a different attitude towards the Italians, for they were seen as "excitable, disorganised and trigger-happy".69 Another line from George O'Neil's memoir expresses the same sentiment: "The only good Italian was a dead one."70 A similar line in E.B. "Dick" Dickinson's war dairy notes, albeit more humorously: "... fleas; thousands and thousands of them attack us towards the end of the month. They can only be on the Italian side."71

In January 1943, South African soldiers set out on their journey home and were greeted at the quayside singing Lady in White upon their arrival at Durban. However, the pilots of the South African Air Force, Engineering Corps, signallers and transport companies remained until the Axis defeat in North Africa in May 1943. One month later, in July, the Allies landed in Sicily.72

As fighting "up North" progressed, the realities of war settled in, making it more difficult to find recruits. Thus significant effort went into marketing, newspaper advertisements, radio programmes, pamphlets, parades and newsreels in the cinema, all in an effort to generate more recruits. In addition, recruitment offices were set up in major towns at police and railway stations and army bases.73 They met with little success. This impending disillusionment also affected those who had already served in the African campaigns; many of them chose not to return to fight.

Liberatori, comrades and brothers-in-arms (3 September 1943-2 May 1945)

He [a German officer] and the Italian commandant made a public display of walking up and down, arm in arm and talking as if they were the most trusting comrades in the world. But we74 suspected something new was in the wind.75

In July 1943, prisoners in a POW camp, among them Cyril Crompton, at San Lorenzo monastery in Padula, near Naples, found their suspicions growing stronger when they were told that they were to be shipped to Bologna and then to Germany. "The Germans were clearly preparing for an expected Italian collapse, and had to set up a defence strategy for Italy against an expected Allied invasion from Sicily."76

Fighting continued across the Mediterranean in Italy with the landing of the 6th South African Armoured Division at Taranto on 20 April 1944, thus shifting the theatre of war. Elements of the division participated in the Battle of Monte Cassino which opened the gateway to Rome. This division consisted of the former 1st South African Division, or rather a mixture of desert war veterans and new recruits, sometimes referred to as the "Tobruk Avengers". Thus, wartime soldiering attitudes were relatively revanchist and the enemy, which included Italy, was much despised, more so than before the humiliating defeat at Tobruk.77

The Allied landing and mobilisation exacerbated existing tensions in Italy. The ageing, mediocre King Victor Emanuel III, after constant urges from his generals, decided that all government ties to the Fascists and Mussolini had to be severed to ensure the monarchy and the traditional Italian state's survival. As a result, Emanuel arrested Mussolini and replaced him with Badoglio. What followed was the Forty Five Days interlude ending on 3 September 1943 with the signing of a secret armistice at Cassabile between Italy and the Allies. Thereafter, a sequence of events followed: Italy was granted the status of "co-belligerent", not Ally; both the king and the marshal fled; the army was dissolved; and German soldiers continued pouring in.78

During the early days of Italy's new status as a liberated nation, South African and other Allied forces were hailed by cheering crowds as "liberatori". This marks the change in South African attitudes. Signaller Joe Openshaw describes the scene and emotions that transpired as the Allies marched through the streets of Italy: "those new tastes and smells and sights were all very titillating. Of course, we were just tourists really - and with a great deal more licence than the normal tourist because we were also the 'liberatori'". Later, Openshaw, like many others, married a signorina he fancied.79

However, this change in attitude was not clear cut. In the ensuing confusion, most of the Italian army scattered and the Germans quickly occupied all of central and northern Italy. While the Allied troops slowly pushed the German resistance to the north, the monarchic government finally declared war on Germany on 13 October 1943.80 In response, an anti-fascist popular resistance movement emerged which fought alongside the Allies. According to the academic, Guido Quazza, the resistance was divided into three strands: The organised political anti-Fascists dominated by the communists who opposed Mussolini; "Justice and Liberty" brigades consisting of radical and democratic anti-Fascist groups; and the socialist PSIUP of disillusioned Fascists.81

Camaraderie did not only develop between Italian partisans and South African soldiers, but also between escaped South African POWs and Italian soldiers. The personal accounts of J. Pieter van Niekerk and Gordon Henderson indicate this. Both had wandered through Italy for nine months, were recaptured and escaped twice, after which time they were hidden by two Italian families in Rome until the Allies arrived. On 4 June 1944, German forces and fascist supporters began evacuating Rome, at which time the host went up to Van Niekerk and prayed: "Dear God ... We thank you for having delivered them back to their loved ones." Van Niekerk expressed his emotional response: ". the moment . was so reverent that I was overcome with emotions." Numerous accounts show similar expressions of gratitude in war memoirs and diaries such as that of Alex Fry. He wrote: "The Italian villagers invited us into their homes and slowly we became accepted as one of the family". In another passage, Fry tells of how Corporal McDonald acted as assistant midwife at the birth of an infant and the Italian child was subsequently named after him as a mark of appreciation.82 Usually the host families were referred to as "friends" or "Italian friends" instead of the previous irreverent name "eyeties". The photograph (Figure 7) illustrates emotions of acceptance from the local Italian inhabitants, which were recierocated by the South AfricansolCiers.83 This is a clear indication of how South African perception of Italians changed.

A sense of camaraderie also developed between Italian guards of POW camps and their inmates. Crompton describes his interaction with officers and guards in a camp on the eve of Italy's surrender, when an officer "tonchcd me on the arm, and nrom behind a large gein exclaimed, 'It won't be long now"'. Similar anecdotes appear in Crompton's memoirs of how the guards left his cell unlocked, and his conversations with guards. In one passage he described this as "a pleasant, albeit short, association".84

Other Italian troops, loyal to Mussolini and his Italian Socialist Republic, continued to fight with the Germans.85 During this phase of the war, Italy altered its position from enemy to ally. Thus South African attitudes changed. Conceptually, Italians were considered fellow comrades and brothers-in-arms, but the term Italian in diary entries refers to civilians who aided and fought alongside them. Italians who supported Mussolini and fought together with the Germans were considered Nazi soldiers.

The "official" government perception of Italy changed with the formal exit and later entrance of Italy into the war, only now on a different side. However, the South African authorities still did not fully accept Italy as an ally, for they held a lower rung, namely that of co-belligerent. In addition, the question arose of what to do with the Italian POWs situated in various camps in the Union. The prisoners were captured whilst flying the banner of Fascist Italy, yet this state no longer existed in its original form. Some prisoners did not have any recollection of the previous liberal Italian democratic regime due to their age. During the course of the war anti-fascist tendencies within the camp also developed. As a result, two factions were formed, some of whom adopted a cooperative attitude towards the South African military authorities. These prisoners were usually demoralised and bored. Other prisoners refused to cooperate, for instance the Camice Nere units or those who felt that they could not renege on their former beliefs. Forced to live together in the confinement of the camps, open conflict arose, so the authorities housed the two opposing factions in different blocks.86

In an attempt to restore peace and utilise the prisoners as a temporary labour force, nineteen external camps were erected in the Cape Province, Orange Free State, Natal and Transvaal. Camps acted as transit centres to transport co-operative prisoners between farms and civil construction sites. Camps also fostered the interaction of Italian nationals and South African citizens, which brought about a significant change in attitude towards the Italian nation, the former enemy.87 Interaction saw the cultivation of what was termed by Sani Gabrielle as the "spirit of Zonderwater".

Exchanges between prisoners and civilians promoted a feeling of reciprocal understanding and friendship between two groups of people who were similar in many respects. At the same time, animosity as a consequence of the war gradually disappeared; indeed, genuine liking arose between Italians and Afrikaners. This was due in part to the Italians' membership of the fascist party, and the tendency of many Afrikaners to sympathise with fascist-inclined movements. There was also the common link of an anti-English demeanour between these two groups. White English-speaking civilians in South Africa took longer to develop feelings of friendship towards Italians due to their prejudices against Latin people, however this also changed over time.88

This positive transformation in South African attitudes toward Italy was, however, not universal. As an eleven-year-old boy, Peter Younghusband's account of the treatment of Italian prisoners on his uncle's farm paints an entirely different image of South African wartime attitudes towards Italy. According to Younghusband, "Oom Boetie Jan had the Italian tied across the tractor by his farm workers and personally flogged him with a sjambok". However, the story does mention that the Department of Defence sued Boetie Jan for his ill-treatment of the prisoner.89 Thus, although negative attitudes towards Italian nationals remained after the armistice, they were mostly isolated cases and not necessarily those of the government and of South African society in general.

On the home front, the war attitudes of South African citizens towards Italians also changed, but on different grounds. South African fathers, sons and brothers were fighting one enemy less, but to many the Italian enemy, formerly aligned with the Axis, was distinguished from the Italians residing in South Africa. However, with the construction of external prisoner-of-war camps, civilians came into contact with Italian nationals. In many cases, this exchange led to a positive shift in sentiment with the result that not only Italian resident in South Africa, but also Italian nationals were viewed in a more favourable light.

Fellow countrymen and countrywomen (2 May 1945-)

One of these days, in Prendini Toffoli's imagination, someone will turn the Zonderwater story into a great South African movie and win an Oscar. Tom Hanks will play the honourable Afrikaner, Colonel Prinsloo and will receive a medal from the Pope for his humane treatment of the enemy; ... and Charlize Theron, the boeremeisie, will have an Italian bun in the oven. It's an epic with all the right elements, and the strangest thing of all is that so few South Africans know anything about it.90

The aftermath of WWII saw the construction of the perilous Du Toit's Kloof and Outeniqua mountain passes; the irrigation schemes in Upington, Vaalharts, Riet River, Olifants River and Loskop; the Mountain Park Hotel in Bulwer; the Madonna delle Grazie Monument; the Louis Botha statue in the grounds below the Union Building and the improvement of Chapman's Peak Drive, Bainskloof and the passes of Tradouw and Sir Lowry's.91 These are all landmarks that act as reminders of Italian POWs who lived in South Africa during WWII. However, the aftermath of the war also saw a shift in attitudes towards the Italian nation as a whole and the arrival of many more Italian residents.

Hostilities ceased in the Italian theatre of war on 2 May 1945.92 But as early as mid-1943 attempts were made to transport Italian repatriates, especially those interned in Southern Rhodesia. Italian internees detained in Southern Rhodesia were sent to the Union by train for the purposes of embarking on Italian repatriation vessels at Port Elizabeth. In some cases Italian mercy ships, such as the SS. Saturnia, were used for repatriation.93 However, the repatriation of POWs in South Africa back to Italy only really commenced in June 1945 and gained momentum in the succeeding year. Despite these efforts to transport Italian internees back to Italy, Zonderwater remained an operational pOw camp until 1947. The "non-collaborators" were repatriated last, only to be imprisoned upon their return by the country for which they had fought. Approximately 3 000 former POWs applied for permission to remain in the Union while waiting for repatriation. However, only 850 ex-POWs were given immediate residency without having to return to their homeland, thus avoiding the rules of the Geneva Convention. The large influx of Italians into the Union in the 1950s and 1960s comprised a large contingent of former Italian POWs accompanied by their families. In addition, an estimated 50 Italians "disappeared" presumably assimilated into South African society, thus avoiding official red tape.94

The immediate post-war period was dominated by anti-Italian feelings in certain quarters, including parliament, where sometimes derogatory remarks were made that Italian nationals were unwelcome.95 After the war, government perception of Italian immigrants as well as the official immigration policy was inconsistent. While Smuts was prime minister, immigration policy took on the character of a typical open-door policy, encouraging the arrival of North Italian labourers who could augment the South African white labour force. On 30 January 1947 Smuts's immigration bill was passed with an 84 to 42 vote. However, some remarks during this sitting clearly indicated the existence of negative attitudes. For instance the leader of the Labour Party, Walter Madley, stated: "Italians are not welcome in this country. I would prefer Germans to Italians."96

After the National Party came to power in the 1948 election, such sentiments became more isolated and preference was given to Italian immigrants - resulting in the most significant wave of Italian immigration in South African history. The 1951 Union census indicates that in the period between 1946 and 1951 the Italian population in South Africa doubled in size. According to Corgatelli, even though census reports fail to indicate this influx explicitly as an "ex-POW influx", this can be extrapolated from the dates of arrival. It would seem that in the aftermath of the war, the Union government came to view the arrival of Italian immigrants in a distinctly positive light. 97

Despite wavering political attitudes towards Italians, diplomatic relations were re-established after the signing of the peace treaty between Rome and Pretoria in 1947. In subsequent years, new cultural and social ties were established between the two states, including the South African Association for cultural relations with Italy, the formation of a committee to establish a South Africa House in Rome and the strengthening of cultural ties in the Fifth Allied Division.98

However, general civilian attitudes towards Italy differed across society. The section of the South African citizenry which opposed Italian immigration included the Reformed churches; the Jewish community; the Anglo Saxons and some Afrikaner nationalists. These four groups stood in opposition to a lenient immigration policy because of religious and/ or racial prejudices. The expression of such negative sentiments formed around deprecating concepts associated with Italians, such as that they were "fascists, cowardly, dirty, poor, Nigger loving and without racial dignity".99 Such expressions played on existing fears and stereotypes entrenched in the white community. In contrast, Afrikaners were also opposed to the influx of Italians, but on different grounds. The common belief amongst this group was that an increase in Catholic Italians would pose a threat to the Afrikaner volk, its religion, customs and chances of gainful employment.100

However, other sections of South African society welcomed the notion of Italian immigration. One of the farms to which POWs were "outplaced" was Leeuwfontein, now Bloemendal. On this farm, prisoners were treated well and the family learnt some Italian. The interaction between these prisoners and the farmer were so positive that some returned to South Africa and found employment on the same farm upon their return with their families.101 This was not an isolated case. Many other farmers who made use of Italian POW labourers during the war also offered enthusiastic praise and wanted to keep the POWs in their employment.102

The aftermath of the war also saw the formation of the Zonderwater Block Association, dedicated to developing bonds of friendship between the two nations and between former Italian POWs. The association has several branches in the main cities of South Africa. The fostering of the

"Zonderwater spirit" gave a new basis for increasingly strong ties between the Italian and South African communities.103

The 1946 Union census undertaken after WWII indicates a numerical increase in the Italian community of South Africa. Most of this increase can be attributed to the relatively substantial influx of women. This is in part explained by the arrival of the "war brides" of South African soldiers who served in Italy, who came to join their husbands. The Italian consulate in Cape Town unofficially estimated that about 2 000 war brides arrived in the post-WWII era. However, many, for varying reasons, subsequently returned to Italy. This large number of war brides is not reflected in the 1946 census, but shows a 90 percent increase in female Italian nationals since the previous census, which revealed a total of 736 women. However, according to a list compiled by the Italian consulate, there were only 81 war brides in the Cape Province in 1951.

In some cases, South African soldiers did not wish to return to the Union after the war. However, this was uncommon because post-WWII Italy was in turmoil, facing political disunity and conflict as well as economic dislocation after serving as one of the theatres of war.104 Furthermore Mussolini's abrupt fall from power left a void in the political sphere which many contenders, most notably the chief organisers of the anti-fascist resistance, wished to fill.105

On 19 August 1963, the Italian training cruiser, Raimondo Montecuccoli, the first Italian naval caller since the war, arrived in Cape Town. During lunch with the men of the Italian and South African navy at the City Hall, the mayor, A.H. Honikman, "urged the Italian visitors not to judge South Africa by what the rest of the world had to say about" Italy. The last Italian naval callers 25 years previously were two submarines. Their arrival made headlines when a local private plane dipped to welcome the Italians, touched a fishing boat's mast - and fell in the sea.106 The Italian visitors were not only entertained at a rugby match in true South African style at Newlands stadium, but also, on a serious note, attended a wreath-laying ceremony at a war memorial on the Sunday before their departure.107

South African attitudes towards Italy were generally positive in the post-war era. In this period South Africa welcomed a large contingent of Italian immigrants - far more than any other African state. Certainly the cumbersome political and economic situation in Italy after the war played a role in many Italians' decision to emigrate. However, the choice of South Africa might indicate that domestic attitudes were of a welcoming nature. In the mid-1990s it was estimated that approximately 120 000 Italian inhabitants, evenly divided between native Italians and individuals of Italian ancestry, were resident in South Africa,108 and South African attitudes towards Italy reached a new, more consistent status quo. They lived together not as foes or brothers-in-arms, but as fellow countrymen and countrywomen.

Conclusion

In South Africa's economic hub, Gauteng, on the northern outskirts of Johannesburg, billboards with large, colourful letters boast: "Monte Cassino - Gauteng's no.1 Entertainment Destination" - the faux Tuscan gambler's paradise. The name acts, ironically, as a reminder of the holy monastery on the summit of Monte Cassino, south-east of Rome that was destroyed in 1944. Thus in the twenty-first century the theatre of war has shifted, but the war now rages between gamblers and the slot machines. However, every year a festival organised by the Italian consulate general and supported by some of the greatest Italian and Italian/South African enterprises is also held there. This festival, L'Italia in Piazza, is a celebration of Italian tradition, culture, cuisine and music where many South Africans celebrate their Italian heritage.

Other physical reminders of South African and Italian involvement in WWII and their common ties can be seen on street name plaques. For instance, Benghazi Road in Cape Town probably refers to the Axis POW camp in Libya. Another example is Tobruk Road in La Colline, Stellenbosch, built in the aftermath of the war for ex-veterans and their families. And in Strandfontein village there is also a road named Tobruk, commemorating fallen and captured comrades. Other examples include the goat tower in front of Fairview estate which tells the story of Michele Agostinelli, the owner, who returned to Cape Town as an ex-POW. The existence of the Zonderwater POW Museum also serves as a reminder of the "South African-Italo" war.109 Indeed, in the post-WWII era, different South African attitudes are held and concomitantly different sentiments are evoked by these reminders of a war long gone.

The emphasis of this paper falls on general South African attitudes towards Italy during and immediately after WWII. More centrally, the study considers how these attitudes fluctuated in relation to Italy's position in the international political arena. These shifting social sentiments are explored chronologically through the course of the war, beginning with South Africa's participation in the "phoney war"; to clashing with Italy and Germany in North and East Africa; to liberating Italians in their homeland and fighting alongside anti-fascist Italian partisans against German occupation; and lastly, the interaction in the aftermath of the war. This article illustrates the variation in attitudes between the Union government; the domestic sphere; and the perceptions of the South African armed forces. Wartime attitudes are identified even though social sentiments showed some differentiation across the spectrum. These attitudes evolved from future enemy, enemy alien, and comrades, to welcoming Italian immigrants.

1. E. Hartshorn, Avenge Tobruk (Purnell & Sons, Cape Town, I960), p 15. [ Links ]

2. J. Crwys-Williams, A Country at War 1939-1945: The Mood of a Nation, Volume 10, World at War Series (Ashanti Publishing, Rivonia, 1992), p 21.

3. Crwys-Williams, A Country at War, pp 2-3.

4. A segregationist classification used to refer to black, Indian and coloured individuals.

5. I.C.B. Dear (ed.), The Oxford Companion to the Second World War (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1995), p 1024.

6. D. Killingray, Fighting for Britain: African Soldiers in the Second World War (Boydell & Brewer, Suffolk, 2010), p 73.

7. Dear (ed.), The Oxford Companion to the Second World War, p 1024.

8. Crwys-Williams, A Country at War, p 21.

9. "No. 26 of 1939: Aliens Registration Act, 1939", Union Gazette Extraordinary No. 2649 (16 June 1939) (Sabinet Online, 2 February 1998), p cxxviii.

10. National Archives of South Africa (hereafter NASA), Cape Town Archives Repository (hereafter KAB): 1/CAL, (Archives vol. 6/1/6), 17/25/2/3, War Measures, Internment, 1939-1945.

11. G. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, 1489-1989 (Trans. Lorenza and Rosella Colombo, Edenvale, Zonderwater Block, 1992), p 291.

12. Crwys-Williams, A Country at War, p 21.

13. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 291.

14. F.R. Scott, "The End of Dominion Status", The American Journal of International Law, 38, 1944, p 38.

15. H. Giliomee and B. Mbenga, Nuwe Geskiedenis van Suid-Afrika (Tafelberg, Cape Town, 2007), p 294.

16. J.A. Brown, The War of a Hundred Days: Springboks in Somalia and Abyssinia 1940-1941, Volume I, World at War Series (Ashanti Publishing, Johannesburg, 1990), p 45.

17. J. Mervis, South Africa in World War II (Whitnall Simonsen, Johannesburg, 1988), p 7.

18. V. Alhadeff, A Newspaper History of South Africa (Don Nelson, Cape Town, 1967), p 52.

19. J. Keene (ed.), South Africa in World War II (Human & Rousseau, Cape Town, 1995), p 22.

20. International Communist Party.

21. E. Bauer, The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War II, Volume 1 (Orbis Publishing, New York, 1972), pp 46, 48, 54.

22. D. Low, British Cartoon Archive http://www.cartoons.ac.uk/search/cartoon item/ italy?page=15 Accessed 5 July 2011.

23. Bauer, The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia, pp 54, 79-80.

24. R. Pankhurst, The Ethiopians: A History (Blackwell, Oxford, 2001), pp 223-226.

25. Brown, The War of a Hundred Days, pp 21, 45.

26. B. Nasson, South Africa at War 1939-1945: A Jacana Pocket History (Jacana Media, uckland Park, 2011), p 9.

27. Crwys-Williams, A Country at War, p 16.

28. Brown, The War of a Hundred Days, p 46.

29. N. Orpen, South African Forces World War II, Volume 1, East African and Abyssinian Campaigns (Purnell, Cape Town, 1968), p 30.

30. R. Collier: The War in the Desert (Time-Life Books, Alexandria, 1977), p 8.

31. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 233.

32. P. Corgatelli, "Tapes and Testimony: Making the Local History of Italians in the Western Cape in the First Half of the 20th Century", MA thesis, UCT, 1989, pp 30, 90.

33. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 233.

34. Italian Fascist Party sections abroad.

35. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, pp 237-238.

36. Ida Peroni interview, in Corgatelli, "Tapes and Testimony", p 188.

37. Antonio Intora interview, in Corgatelli, "Tapes and Testimony", p 207.

38. Corgatelli, "Tapes and Testimony", p 81.

39. Brown, The War of a Hundred Days, p 47.

40. Corgatelli, "Tapes and Testimony", p 81; H.J. Martin and N. Orpen, South African Forces World War II, Volume VII, Military and Industrial Organization 1939-1945 (Purnell, Cape Town, 1979), p 66.

41. Corgatelli, "Tapes and Testimony", p 81.

42. NASA, KAB: 1/SMT, (Archives vol. 9, 8, 11), War Measures, Control of Persons, Enemy Subject Exemption from Internment, 1940-1942.

43. Corgatelli, "Tapes and Testimony", p 81.

44. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, pp 294-295.

45. NASA, KAB: 1/CAL, (Archives vol. 6/1/6), 17/25/2, War Measures, Internment, '39 45.

46. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, pp 294-295.

47. B. Moore and K. Fedorowich (eds), Prisoners of War and their Captors in World War II (Berg, Oxford, 1996), p 27.

48. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, pp 298, 299.

49. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 296.

50. NASA, KAB: SWP, (Archives vol. 10), 49A, Allowances to dependents of internees circulars and instructions, 1939-1941.

51. Crwys-Williams, A Country at War, p 311.

52. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, pp 294, 296-297.

53. L. Gilbert: British Cartoon Archive http://www.cartoons.ac.uk/search/cartoon item/italy?page= 15 Accessed 2 November 2011.

54. Gilbert, British Cartoon Archive http://www.cartoons.ac.uk/search/cartoon item/Mussolini?page=9 Accessed 2 November 2011.

55. Collier, The War in the Desert, p 8.

56. Dear (ed.), The Oxford Companion to the Second World War, p 315.

57. A. Moorhead, The End in Africa (Hamish Hamilton, London, 1943), p 12.

58. Crwys-Williams, A Country at War, p 151.

59. Brown, The War of a Hundred Days, p 48.

60. J. Bourhill, Come Back to Portofino: Through Italy with the 6th South African Armoured Division (30° South Publishers, Johannesburg, 2011), pp 21-22.

61. C.J. Jacobs, '"n Evaluering van die Rol van die Eerste Suid-Afrikaanse Infantriedivisie tydens die Eerste Slag van El Alamein, 1 tot 30 Julie 1942", MA thesis, University of Stellenbosch, 1988, p 20.

62. Mervis, South Africa in World War II, p 26.

63. C. Crompton and P. Johnson, Luck's Favours: Two South African Second World War Memoirs (Echoing Green Press, Fish Hoek, 2010), p 19.

64. According to some sources the number of soldiers captured was 33 000.

65. K. Horn, "Narratives from North Africa: South African Prisoner-of-war Experience following the Fall of Tobruk, June 1942", Historia, 56, 2, November 2011, p 94.

66. 1st Natal Carbineers, the Duke of Edinburgh's Own Rifles and the 1st/3rd Transvaal Scottish.

67. Jacobs, "Evaluering van die Rol van die Eerste Suid-Afrikaanse Infantriedivisie", p 24.

68. G. Stegmann, The Lights of Freedom (Just Done Publishing, Durban, 2007), p 85.

69. Ike Rosmarin, quoted in L. Maxwell, Captives Courageous: South African Prisoners of War, Volume 9, World at War Series (Ashanti Publishing, Johannesburg, 1992), p 17.

70. G. O'Neil, Enough for Survival (Grocott & Sherry, Grahamstown, 1988), p 28.

71. E.B. Dickinson, From Jo'burg to Dresden: A World War II Diary (Privately published, Mossel Bay, 2010) p 87.

72. Bourhill, Come Back to Portofino, p 30.

73. Bourhill, Come Back to Portofino, p 29.

74. This excerpt describes the change in tide noticed by prisoners in a POW camp, among them Crompton, at II San Lorenzo monastery in Padula, some one hundred and fifty kilometres east and south of Naples. Crompton was captured at the Battle of Sidi Rezegh by Germans and was handed over to the Italians or "Eyeties", as they were called by the prisoners. He was transported to Derna and then Naples.

75. Crompton and Johnson, Luck's Favours, p 56.

76. Crompton and Johnson, Luck's Favours, pp 56-57.

77. Bourhill, Come Back to Portofino, pp 32-33.

78. P. Ginsborg, A History of Contemporary Italy 1943-1980 (Penguin Books, London, 1990), pp 12-14.

79. J. Kros, War in Italy with the South Africans from Taranto to the Alps, South Africans at War Series (Ashanti Publishing, Rivonia, 1992), pp 19-20.

80. Dear (ed.), The Oxford Companion to the Second World War, p 1332.

81. Ginsborg, A History of Contemporary Italy 1943-1980, pp 14-15.

82. A. Fry, How I Won the War: Personal Accounts of World War 2 (Just Done Publishing, Durban, 2007), pp 9, 51.

83. Kros, War in Italy withthe South Africans from Taranto to the Alps, p 115.

84. Crompton and Johnson, Luck's Favours, pp 166-169.

85. Ginsborg, A History of Contemporary Italy, p 15.

86. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 299.

87. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, pp 300-301.

88. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 301.

89. Crwys-Williams, A Country at War, p 145.

90. Prendini Toffoli quoted in R. Buranello, "Between Fact and Fiction: Italian Immigration to South Africa", Unpublished paper presented at the Cultures of Migration conference, University of Staten Island, 22-24 June 2007, pp 25-26.

91. I. Ferreira, Italian Footprints in South Africa (Jacana Media, Auckland Park, 2009), pp 77, 150, 152-154.

92. Dear (ed.), The Oxford Companion to the Second World War, pp 1336-1337.

93. NASA, KAB: PIO, (Archives vol. 596), 26299E, Immigration Papers, Italian internees detained in Southern Rhodesia, 1943.

94. Ferreira, Italian Footprints in South Africa, p 150; Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, pp 302, 308.

95. Ferreira, Italian Footprints in South Africa, p 150; Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, pp 302, 308.

96. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 309.

97. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 310, 315; Corgatelli, "Tapes and Testimony", pp 29-32, 36.

98. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 309.

99. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 308.

100. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 308.

101. Ferreira, Italian Footprints in South Africa, p 152.

102. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 308.

103. Sani, History of the Italians in South Africa, p 301, 302.

104. Corgatelli, "Tapes and Testimony", pp 30, 37, 41.

105. Ginsborg, A History of Contemporary Italy, pp 39, 98.

106. "Cape Council Entertains Sailors", Pretoria News, 21 August 1963; "Italian Trainee Cruiser to Visit the Cape", The Cape Times, 11 April 1963.

107. NASA, KAB: 3/CT, (Archives vol. 4/1/11/74), G5/23/63, General purposes festivities, Visit by the Italian cruiser Raimondo Montecuccoli, 1963.

108. Buranello, "Between Fact and Fiction", p 25.

109. Ferreira, Italian Footprints in South Africa, p 162.