Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Historia

versão On-line ISSN 2309-8392

versão impressa ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.58 no.1 Durban Jan. 2013

ARTICLES ARTIKELS

Imperial running dogs or wild geese reporters? Irish journalists in South Africa

Donal P. McCracken

Senior professor of History in the Centre for Communication, Media and Society at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. He has eleven books and five edited books to his name, primarily on Irish and botanical history. He is chair of the Alan Paton Centre and Struggle Archive Advisory Board

ABSTRACT

In recent years there has developed ex nihil, and thanks in part to the Newspaper and Periodical History Forum of Ireland, a keen interest in the history of the Irish press. However, something of a lacuna exists when it comes to Irish journalists working in the British Empire. These fell into two categories: those who were war correspondents or who worked for a news- gathering agency; and those Irish journalists who settled in the empire. The latter were particularly numerous in British South African colonies and the adjoining Boer republics. This article looks at this phenomenon, where no fewer than 40 newspapers at one time or another had an Irish editor or Irish senior journalist. The article examines the reason for this prominence of Irish journalists, the factors which drew them to South Africa, as well the stance taken by them on political allegiance. The paper discusses differences between journalists in British Natal and the Cape and those in the Boer Transvaal and Orange Free State republics. The role of Irish war correspondents at the time of the Anglo-Boer War also features.

Key words: Irish diaspora; journalists; media history

OPSOMMING

In die afgelope tyd het 'n ex nihil ontwikkel, en deels te danke aan die Newspaper and Periodical History Forum of Ireland, 'n besondere belangstelling in die geskiedenis van die Ierse pers. Maar ietwat van 'n lemte bestaan wanneer dit kom by lerse joernaliste wat in the Britse Ryk gewerk het. Die val in twee kategoriee: die wat oorlogskorrespondente was en die wat vir nuus insamelings agentsakppe gewerk het; en die lerse joernaliste wat hulle in die ryk gevestig het. Laasgenoemde was veral talryk in die Britse kolonies in Suid-Afrika en die Boere republieke. Die artikel ondersoek die fenomeen waar nie minder as 40 koerante een of ander tyd 'n lerse redakteur of 'n senior lerse joernalis gehad het. Die artikel ondersoek die redes vir die prominensie van lerse joernaliste, die faktore wat hulle na Suid-Afrika gelok het sowel as die politieke posisie wat hulle ingeneem het. Daar is ook gekyk na die verskille tussen lerse joernaliste in die Kaap, Natal, Transvaal en die Oranje Vrystaat. Die rol van lerse journaliste gedurende die Anglo-Boereoorlog word ook ondersoek.

Sleutelwoorde: lerse diaspora; joernaliste; media geskiedenis

Historiography of the Irish in South Africa

The study of the Irish diaspora is an international phenomenon. Outside of Ireland, there are chairs of Irish history at such universities as Concordia, Fordham, Liverpool, Loyola Marymount, Melbourne, Otago, Oxford, St Mary's (Canada), New South Wales, Notre Dame and Villanova. There are also annual conferences relating to the Irish diaspora and Irish studies in Australia, Brazil, Britain and the United States of America. Journals and series pertaining to the Irish diaspora and published outside Ireland are produced in Australia, France, South Africa, South America and the United States of America. These include such accredited journals as Éire-Ireland and Études Irlandaises. There is also the subscription-basis run internet forum by Murray State University devoted to the academic study of the Irish diaspora.

In South Africa the study of Irish migration to the subcontinent has been a relatively recent matter. In his seminal work, The Irish Diaspora: A Primer, Professor Donald Akenson of Queens University Ontario observed the following:

The historiography of the Irish in South Africa is bizarre because until very recently there was almost none. This would be unusual in most countries, but considering that we are here dealing with South Africa - the single most racially conscious modernized society in the world - the omission is extraordinary. Beginning in the 1980s Professor Donal McCracken has organized ex nihilo Irish studies in South Africa, producing two excellent studies and one solid academic journal.1

The Ireland and Southern African Project which commenced in 1989 and centred on the University of KwaZulu-Natal, publishes the occasional series Southern African-Irish Studies. To date, four volumes have been published comprising 56 chapters from scholars in nine universities in South Africa, Ireland, Britain, Malta and Canada.2

It is significant that one of Akenson's chapters in Occasional Papers on the Irish in South Africa has the cryptic title "Hardly an Information Glut". The historian of the Irish diaspora and southern Africa has lean materials with which to work. Unlike America and Australia there is no cohort of emigrant letters which have survived. There are equally few diaries extant. Because of this, very few published Irish-South African manuscripts have appeared, a noted exception being Joy Brain's edited volume The Cape Diary of Bishop Griffith, 1837-1839.3 There are a few biographies and autobiographies, including Ken Smith's Alfred Aylward: The Tireless Agitator and Leslie McCracken's New Light at the Cape of Good Hope: William Porter the Father of Cape Liberalism.4 But there still remain key Irish-South African figures with no published biography, such as Hamilton Ross, Thomas Uppington and Albert Hime. In the field of autobiography there is the much-mined An Ulsterman in Africa written by the only Irishman to serve in Smuts's cabinet, R.H. Henderson.5

Manuscript caches of Irish-South African documents are rare. There are the Gately papers in East London Museum, and both the National Library of Ireland manuscript division and the National Archives of Ireland have some relevant material, such as documents relating to Irish who fought in the Frontier Wars or the Anglo-Boer Wars. A survey of Irishmen who fought in South Africa over a 200-year period is contained in S. Monick's Shamrock and Springbok.6 Regarding the Anglo-Boer War, there are Donal McCracken's Forgotten Protest and MacBride's Brigade. And on Irish ne'er- do-wells, there is Charles van Onselen's Masked Raiders.7 No book exists on the history of the Irish contribution in the mission field in South Africa and the only volume on a specific Irish settlement scheme is Graham Dickason's Irish Settlers to the Cape: A History of the Clanwilliam 1820 Settlers from Cork Harbour, published in 1973.8 In the case of Irish journalists, the historian has little option but to build up the picture from many sources, such as newspapers themselves; biographies, such as Barry Ronan's Forty South African Years; and histories of newspapers and studies of newspaper editors.9 The only existing overall analysis of the topic is Patricia McCracken's article, "Shaping the Times: Irish Journalists" in volume two of Southern African-Irish Studies.10

The wild geese

Southern Africa was never one of the great regions of settlement for those hundreds of thousands of Irish who, mainly for economic reasons, fled their country in the generations following the Great Famine of 1845-1850. While the United States, Canada, the Australian colonies and parts of Great Britain, such as Liverpool, north London and Glasgow, became havens for these disposed migrants, South Africa attracted relatively few Irish emigrants.11 There were various reasons for this, not least the fact that there were relatively few free or cheap passages to the Cape; there was no Irish tradition of going to Africa and, as such, little chain migration until the 1890s; and, finally, South Africa had a reputation in Ireland for being a wild and savage place where poor Irish settlers were shabbily treated.

An exception to this trend, though, was created by the British army. During the nineteenth century it ensured that tens of thousands of Irish soldiers, both in Irish and non-Irish regiments, came to Africa. In the Anglo- Boer War alone this amounted to around 30 000 men, a consequence of which was an upturn in Irish immigration in the Edwardian era. It is an interesting reflection on the politics of the age that much more publicity was, and indeed subsequently has been given, to the approximate 500 Irish commandos who fought alongside the Boers than to the eleven full Irish regiments in the British army who fought against them.12

While much has been written generally about the Irish diaspora, not surprisingly this has tended to focus on the heartlands of Irish settlement rather than the peripheries. Nonetheless, in South America and India, as well as South Africa, the Irish experience has been chronicled to a certain extent. Yet, even after a generation of scholarship, lacunae still exist. These include a scarcity of publications on the Irish diaspora and gender as well as studies of actual trades and professions in relation to the Irish diaspora.

The only permanent Irish community on the African continent has been in what today is South Africa. This dates from the 1780s and has been studied by the Ireland and Southern African Project, which has to date published four volumes in the occasional series Southern African-Irish Studies. In his seminal book The Irish Diaspora: A Primer, D.H. Akenson alluded to the Irish experience in South Africa as being at one end of a spectrum of Irish migrant experience, with the United States at the other.13 The difference between the Irish experience in southern Africa and that on the eastern seaboard of the United States relates primarily to factors around gender, age and occupation. While it is difficult to make generalisations over a lengthy timespan, the principal characteristics of Irish immigration reflect a situation where in the Victorian era more males arrived in southern Africa than females; where the religious balance was more equitable; where there were in this early period more married women than unmarried; where settlement was frequently transitory (individuals moving on to Australia or returning back to Ireland); and where the Irish tended to congregate in a few specific occupations.14

This last phenomenon is particularly interesting as it created an illusion. Because a full quarter of the Cape Mounted Police were Irish and, as in New York, policemen with Irish brogues were a common feature in the streets of Cape Town, there was an impression created that the Irish were, in fact, more numerous at the Cape, and to a degree in Natal and in Johannesburg, than they were in terms of actual numbers. Similar observations might be made about the Irish Catholic priests who dominated the diocese of the Eastern Cape in the Victorian era. Retailing was another such occupation in which the Irish clustered, be it in John Orr's; R.H. Henderson' McCullough & Bothwell; McNamee's; or William Cuthbert's boot and shoe emporia.15 Equally, it is interesting to note the large number of colonial officials who were Anglo-Irish, including a quarter of the Cape's governors. It is said that when Sir Lowry Cole arrived at the Breakwater pier in September 1828, people in the crowd were heard to grumble that "another Irishman" had been sent to rule over them.16

But despite all this and the publicity given in South African colonial and republican newspapers annually to St Patrick's Day shenanigans, the fact remains that South Africa attracted few Irish, perhaps 60 000 ethnic Irish, including second-generation or "colonial Irish", by the Edwardian era. Of course, that said, South Africa did not attract a great many settlers of any variety, as illustrated by the fact that the Irish could boast to being the fifth largest immigrant group at the Cape in 1904.

The conformity of nonconformity

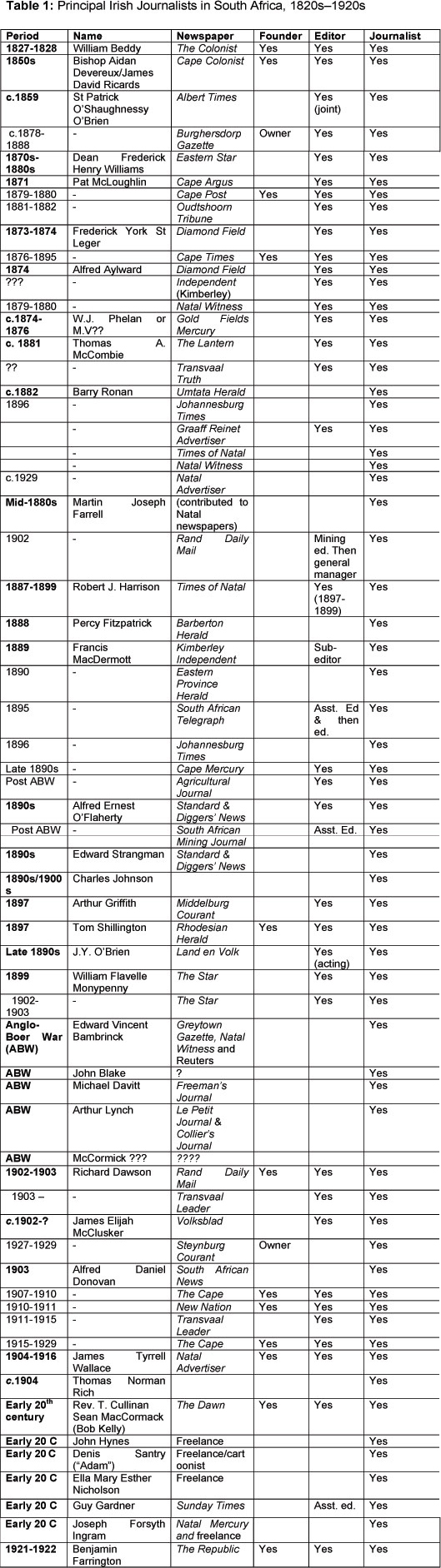

Newspapers deal with the moment and, by their very nature, are ephemerae. Newspaper management and employment records are similarly elusive for the historian. Even such a simple but fundamental fact as the circulation figure of a colonial newspaper is usually impossible to find. It is also impossible, therefore, to put a figure on the number of Irish journalists who worked on South African newspapers in the colonial era. All we know is that there were plenty of them, certainly out of proportion to the number of Irish in the region. Furthermore, as can be seen from the table, there was a disproportionate number of Irish newspaper editors in South Africa in the period and even some Irish founders of newspapers.17

The question immediately arises as to why there was this over- representation. In no small part the answer lies in the nature of nineteenth century Irish society. Ireland had gained a national primary schooling system from as early as 1831, so by the mid-nineteenth century one had a society which, while essentially still peasant-based was nonetheless more literate than one might expect given the economic plight especially of the rural poor.18 But it went further. Education and, it has to be said, anglicisation were key factors in the rise of a Catholic lower-middle class. The decline in the Irish language, famously encouraged by the Irish leader Daniel O'Connell, the Liberator, and the fact that the medium of instruction in the national schools was English and not Gaelic, meant that there emerged young upwardly-mobile, English-speaking and English-literate Irish youths. Many of these were drawn to the printing trade, journalism and school teaching. The ranks of the revolutionaries who eventually took Ireland to independence in 1922 were packed with such individuals. Then, conversely, in the Irish Protestant community, there was a tradition of learning which was to find its pinnacle in the flowering of Anglo-Irish literature in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Ironically, many Irish Protestants were to the forefront of promoting and reviving the Irish language, the most prominent being Douglas Hyde.19

If one adds to the formula that those Irish who came to South Africa were slightly older than the norm for Irish migration, and that they tended to be slightly more affluent than was usual for an Irish migrant to the United States, it is hardly surprising that there was an attraction to printing and journalism. And indeed a push-factor which brought into the region several established Irish printers and journalist, was that in the 1890s the Irish printing trade fell into a serious depression.

But having arrived in South Africa, what then happened to the Irish journalist? While much has been made of Irish "political trouble makers" in the British Empire, as distinct from a noticeable cohort of Irish immigrants in New York, the reality is that in many instances the Irish did not get off the boat in Sydney, Kingston or Cape Town with a burning grudge against England for her policies in Ireland. Indeed, one can go further by stating that the Irish frequently were quite happy to be absorbed into mainstream colonial society, accepting without question colonial norms and prejudices, in particular in relation to indigenous peoples.20 This is not to deny Irish Fenian republican activity around the empire in the 1880s, but the picture is neither uniform nor consistent in the stance taken by Irish immigrant populations.21 The evidence would seem to suggest that many Irish, having turned their backs on the deprivations and political inequities at home all too soon were quite happy to assume the political status quo of their newly adopted country. And when it came to the journalism profession, it is remarkable how amenable members of the Irish press corps in South Africa were to accepting the political status quo, be it in Natal, "the last outpost of the British Empire" or in the anti-British.

Irish journalists in British South Africa

Not surprisingly, the Cape was where the first Irish journalists in the subcontinent were to be found. This dates from the 1820s, when William Beddy from Dublin edited the short-lived The Colonist (November 1827- September 1828).22 As the Victorian era dawned and progressed, more and more Irish journalists were to be found on Cape newspapers, many of them holding prominent positions. Some of these were obscure rural papers such as the Albert Times, the Umtata Herald and the Graaff Reinet Advertiser. No copy of the Irish-owned and Cradock-based The Dawn has ever been located, though we know that it was run by Rev. T. Cullinan, Sean Maccormack and a Scot called Bob Kelly.23 On the other hand, there were also mainline urban newspapers such as the Cape Argus, Oudtshoon Tribune and Eastern Province Herald which had Irish journalists on the staff.

The most noteworthy of the Irish pressmen in the Cape was Frederick York St Leger. In 1876, along with R.W. Murray, he founded South Africa's first daily newspaper, the Cape Times and proceeded to edit it until 1896.24 A combination of scholarly intellect and missionary zeal, combined with a good business sense, soon ensured its success and gained for it the reputation of being South Africa's newspaper of record. Priced at only one penny, less than a third of its rival's selling price, it meant that the Cape Times was widely distributed and read.

Patriotic to the Boer republics

If the tendency in the Cape and Natal was for Irish journalists to go with the established order, the same could be said for their fellow countrymen who worked in the Transvaal. In the Boer republics the tendency was for Irish journalists to be sympathetic to the republican regimes, even when that meant harming their own newspaper which, being published in English, naturally depended on a British and frequently Uitlander readership to survive. The most noted case in point was the Middelburg Courant in the Transvaal. Into this dusty dorp in May 1897 came a young man named Arthur Griffith. Eight years later he would form an organisation back home in Ireland called Sinn Féin and a quarter of a century after that he would be the first leader of an independent Ireland.

An exile from the downturn in the Irish printing trade, Griffith found himself out in the Transvaal and editing a rural English-language newspaper. The saga of Griffith's destroying this organ of the Eastern Transvaal has been traced by Patricia McCracken.25 In summary, Griffith wrote stirring editorials in favour of the Transvaal government. Needless to say, this alienated the local white English-speaking population who stopped buying the newspaper. The Boers had their own newspapers and did not rush to fill the lacuna. The result was that after six months the paper ceased publication and Griffith left town. The significance of this is greater in the Irish context than South African, because Griffith went on to edit an influential and iconic advanced nationalist newspaper in Ireland called the United Irishman. It is regrettable that the only file of the Middelburg Courant for the period Griffith edited the newspaper has long been missing from the National Library in Pretoria.

One would have thought that a serious drawback to being a pressman in the Transvaal Republic would have been language, but this does not appear to have deterred Irish journalists, who in any case usually worked for newspapers which were primarily published in English. Nonetheless, knowledge of Afrikaans or Dutch was an advantage and essential in such newspapers as Land en Volk (J.Y. O'Brien) and Volksblad (James McCluster). A. Cahill, on the staff of the Transvaal Argus, was described by a fellow Irish journalist as "one of nature's gentlemen, a loyal friend and a good worker, especially valuable owning to his knowledge of the Dutch language. He started life as a compositor in Kimberley and worked up his shorthand in order to become a journalist".26

Though there is a distinct scarcity of source material relating to the Irish diaspora and South Africa, one rich mine, ably exploited by the late T.K. Daniel, is newspaper reports of St Patrick Day events. These were often the product of having an Irish staffer on hand for what was frequently a boisterous event. This could also lead to some amusing if malicious, editorial comments. One Irish journalist recorded, "I make another sortie to the Irish banquet, make microscopic notes, secure the final slips from the speech-taking reporters, drink two patriotic toasts, and rush back to work".27 It is to be noted that invariably a toast to "the press" was proposed at these annual Irish functions.

The first report of an Irish dinner in Johannesburg was in the Standard and Transvaal Mining Chronicle and stated that it would have delighted the owner of a dog kennel.28 And T.K. Daniel cites O'Flaherty at the Standard and Diggers' News reporting on the Irish in Barberton "heartily" sympathising with the Transvaal government and "declining to believe that the Durban Irishmen will join the cry of the capitalists". Two weeks later O'Flaherty published a resolution by some Grahamstown Irish who had repudiated the actions of the Irishmen on the Rand in forming a commando and who "express strong and unswerving loyalty to Britain".29 Such pot- stirring was par for the course within the Irish South African press world.

Rebels to conformity

If most Irish journalists were generally accepting of the established order, be it colonial or republic, there were some very notable exceptions, the most notorious of whom was Alfred Aylward from Wexford. He turned up at the diamond field diggings in the early 1870s erroneously calling himself Dr Aylward and working as a medical doctor. He caused endless trouble for the British authorities as a firebrand stirring up the white diggers at any opportunity. Following a drunken and violent brawl, Aylward ended up for over a year in Klipdrift goal. But it was later in 1874, as editor of the Diamond Field, that Aylward caused most damage for the authorities. It was said that he and the rival editor of the pro-government Diamond News used to sit together in a bar thinking up ways to abuse each other in their respective newspapers. Matters came to a head with the diggers' so-called Black Flag rebellion, which "General" Aylward help instigate, but in which he did not take a terribly active part. In May 1875 he had lost his editor's chair, though he did edit Kimberley's Independent after this for a short while.

Several years later, having led the Lydenberg Volunteer Corps in the South African Republic's Eastern Transvaal against Sekhukhune, Aylward turned up in Pietermaritzburg. This was the English-establishment and British army garrison capital of the Colony of Natal. Here he edited the Natal Witness. It was something of a repeat of the Griffith saga in Middelburg, because Aylward had no regard for the pro-British sentiments of his white readership. "Wake up Maritzburg", he ranted in his editorial column. Not surprisingly, it was said that during his time as editor, "there was mud in the streets and mud in the press". With talk of Aylward being lynched, one morning he quietly slipped out of town and was next heard of fighting alongside the Boers at the battle of Majuba in February 1881.30

Over in Pilgrim's Rest in the Eastern Transvaal was another nonconformist Irish newspaper editor. In the mid-1870s, the Gold Fields Mercury was edited by the irascible W.J. Phelan. He was against the government, and it mattered not that that the government in this case was Boer rather than British. Phelan, like Aylward, lacked subtlety, something which made his newspaper interesting and exciting reading. However, also like Aylward, he overstepped the boundaries once too often and found himself imprisoned, albeit for a brief period.

Less crude than Phelan, but as dangerous a journalist in the Transvaal Republic, was Alfred Ernest O'Flaherty (1869-1945). He had been a Sanskrit gold medallist at Oxford University. In the 1890s he found himself walking a perilous tightrope when editing the Johannesburg-based, but generally pro-Kruger government, mainly English-medium Standard and Diggers' News. But in the same town, the rival to the Standard and Diggers' News was The Star.

The Star was edited by yet another Irishman, William Flavelle Monypenny. He had been recruited straight from the London Times. His politics were imperial and The Star was in the front line in demanding political reform in the Transvaal Republic and extended rights for Uitlanders. As war loomed and the situation became more heated Monypenny had to flee the country ahead of a warrant for high treason. He returned to edit The Star after the war, but did not last long, resigning in protest over the importation of Chinese labour for the gold mines. He moved to London to work on The Times, of which he eventually became a director, and to write the first two volumes of the official biography of the Victorian statesman Benjamin Disraeli.

But there was another giant in the South African press world of this period. Monypenny and O'Flaherty's intellectual equal in the South African- Irish press corps was undoubtedly Benjamin Farrington (1891-1974), who lectured in classics at the University College at Cape Town and who occasionally wrote also for the press. A devoted Irish republican and later as dedicated a communist, Farrington was responsible for launching and editing a fortnightly known as The Republic. This lasted for 41 issues during very dramatic times in Ireland and South Africa, including the Anglo-Irish War, the signing of the treaty granting dominion status to 26 Irish counties (the Irish Free State) and the beginning of the Irish Civil War. In South Africa the period witnessed the Rand Revolt.

The Republic, which had 16 pages and sold for four pence a copy, had a circulation of about 2 000. It was sold at the Central News Agency (CNA) but was banned by South African Railways from their platform kiosks. Its politics were overtly pro-Sinn Féin and anti-British. In Ireland, the Weekly Freeman described The Republic as "an ably and well arranged paper". One of the contributors was Ella Nicholson, an Irishwoman who lived in Cape Town and who also published various political tracts, including "The truth shall make you free": Dedicated to All Fair Minded British Subjects. By an Irishwoman.31 The Republic was destroyed by infighting among the Irish community in southern Africa, who split over acceptance or rejection of the Anglo-Irish Treaty.32

Rebelling somewhat differently against the established order from Farrington was Alfred Daniel Donovan (1878-1929), a Catholic born in Cork who was successively a journalist with the South African News, The Cape, the New Nation and the Transvaal Leader, before returning again to The Cape. While editing The Cape (1907-1910) Donovan was the leading exponent in the Cape Colony who advocated a transformation of mindset from colonial to national. In particular, he pressed for the abandonment of the everyday usage in white society of the term "home" to denote England, and "colonial" to denote a white born in South Africa.33

Irish war correspondents

There is another category of Irish journalists in South Africa in this late colonial era, and that is the war correspondent. By definition these tended not to be local South African-Irish or colonial Irish, as they were sometimes called, but itinerants who came and went. They were nearly all confined to the period of the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902). An exception, though, was Cecil James Sibbett (1881-1967) from Belfast, who aged eighteen arrived with his father in Cape Town in 1897. During the Anglo-Boer War he was a war correspondent joining the rat-pack which followed Lord Roberts's advance up through the Orange Free State and on to Johannesburg and Pretoria. Later he would become an employee of Rhodes and a well-known public figure in Cape society.34 Richard Dawson, formerly member of parliament, is another case. He came out to fight for the British and ended up as founder of the celebrated Rand Daily Mail.

During the Anglo-Boer War there were over 260 journalists employed by over 70 newspapers and journals, mainly attached to the British army during this 36-month conflict. There were also nearly 50 journalists employed by five news-gathering agencies.35 The largest of these agencies was Reuters, who had about 28 journalists working in South Africa during the war. These included an Irish woman called Miss McGuire. But more significant was the Irishman M.J.M. Bellasyse, the bureau chief at the beginning of the war. He was forced out of his job by the British authorities because of his alleged sympathies with the Boer cause.36

But the most famous Irish war correspondent was very different from the hacks who followed the Roberts' media circus up through the Orange Free State into the Transvaal. Between March and May 1900 the former Irish advanced nationalist MP Michael Davitt visited the Transvaal Republic under the guise of writing for the Dublin newspaper the Freeman's Journal. He met the great and famous in the two republics and sent home strongly worded pro-Boer reports. Part of one dated Pretoria 25 April 1900, ran as follows:

Farewell Pretoria! You will soon cease to be capital of a nation. The enemy of nationhood will make you another of his "centres of civilization". Brothels, paupers, hypocrites, gospel mongers in the pay of British mammon, and all the other inseparable accompaniments of Anglo-Saxon rogers will replace the kind of life you have been familiar with; not a perfect life, not a blameless one, but one infinitely better, cleaner, and more truly civilised than the one which will begin here the day the ensign of England will float once more over a defeated Nationality.37

No known Irish journalist died because of his or her reporting in a South African conflict, unlike the hapless Frank Power of the Freeman's Journal who was cut to pieces in the Sudan during the British debacle there of 1885 or Edmond O'Donovan of the Daily News who met his nadir in the same conflict with "a Sudanese spear the size of a shovel".38 There were, however, many in the British establishment who were keen that one Irishman who claimed to be a war correspondent with the Boer army should hang from the end of a rope. This was the Irish-Australian, Arthur Lynch (1861-1934).

Lynch was able, a trained engineer, a trained medical doctor, a linguist, a writer and a self-proclaimed Irish nationalist who had hung around Maud Gonne and the advanced Irish nationalist set in Paris prior to the outbreak of hostilities in South Africa. Pompous and self-important, Lynch was not particularly popular with the Irish republican inner circle and the news that he had arrived in the Transvaal in January 1900 did not go down terribly well with the Irish under John Blake and John MacBride who were leading an Irish commando of some 500 men down at Ladysmith, where they were helping with the siege of that garrison town. Lynch had managed to slip by the Royal Navy on the grounds that he was an accredited newspaper reporter for Black and White, Collier's Weekly and Le Petit Journal.39

In fact, Lynch's purpose was to form another Irish commando and fight for the Boers. With the help of a shadowy figure called Gillingham he achieved that although his fighting exploits proved very limited. There was bad blood between the two Irish commandos. Lynch was only in South Africa for about six months because the British had swept up to the Mozambique border. Lynch returned to Paris and in 1901 successfully stood for the British parliament for Galway. On arrival in England from Paris to take up his seat, he was arrested on a charge of treason and subsequently found guilty. Though Lynch had taken out Transvaal citizenship, this was after hostilities had commenced, so unlike the other Irish who had become burghers before the outbreak of war, he was in trouble. But in the end he was granted a pardon and settled down to be a doctor and writer, ironically helping the British with army recruitment in Ireland during the First World War.

Transitory nature of the Irish journalist

A noted feature of later nineteenth-century Irish journalists in South Africa was their restlessness. They were forever moving from paper to paper and eventually sometimes out of the region itself. Several examples are Alfred Donovan (1878-1927) and the more famous Dublin-born Barry Ronan. As will be seen from the table, Donovan worked for five newspapers in the Cape and the Transvaal, one of which, The Cape, he re-founded after it had been extinct for five years. Barry Ronan, more famous today as an author than journalist, was on the staff of six newspapers during a journalistic career which spanned 47 years (1882-1929). A less happy example is Pat McLoughlin (1835-1882), who edited three South African newspapers, committing suicide while editor of the Oudtshoorn Tribune.

Then there were those Irish journalists who left the profession, such as F.D. McDermott, who became a farmer. James Tyrrell Wallace was a journalist from 1904 until 1916, before becoming manager of the King's Theatre in Durban and twice being chairman of the South African Olympic Games selection committee. An opening now closed to journalists in nineteenth-century South Africa was recalled by Barry Ronan in his charming autobiography Forty South African Years:

There were several peculiarities or customs in the nineteenth-century South African legal system. A court translator might after some time qualify to be considered to become a magistrate. And a newspaper reporter could become an attorney - "a limb of the law" - if he attended a set number of sittings of the high court.40

The question of Irish identity needs to be raised, especially regarding those Irish journalists who might be seen as part of the British milieu, such as St Leger, Ronan and Monypenny. The answer is generally yes. Not only were they looked upon as Irish, and by inference, something a little peculiar, but they themselves regarded themselves as Irish. But this was not the bitterness of the émigré, but rather the quiet sense of origin and forlorn regret at missing a place frozen in the past. But also being Irish opened doors which might otherwise be closed, especially in the Boer republics. It was that peculiar affinity which made others shake their heads at the incongruity of a Calvinist/Catholic mutual respect. As Fydell Edmund Garrett, St Leger's successor in the editor's chair in the Cape Times observed of this duo, "Providence in its infinite indulgence has spared us the task of reconciling both the Dutch and the Irish gifts of recalcitrance".

Conclusion

As Table 1 illustrates, Irish journalists in South Africa were widely spread across the newspaper world. They were traditional "Irish wild geese" in that they retained their Irish-ness and sometimes Irish wayward manners of behaviour, but equally it can be argued that they were quick to assimilate into the outlook, prejudices and attitudes of the region where they chose to settle. Most Irish journalists in the Cape or Natal were broadly sympathetic to the imperial status quo. Similarly, in the Boer republics, their sympathy tended to be on the side of the republics. But accepting this, there were many who maintained a stubborn "agin the government" attitude, whatever form that government took. But whatever their political leanings, the phenomenon of the Irish journalist quickly faded with South African unification. Indeed, within a generation the phenomenon of the Irish-South African journalist had all but vanished, though in the early 1990s an echo in the South African broadcasting world existed with such Irish-South African broadcasters as Martin Bailey, Patricia Kerr, Paddy O'Byrne, John Robbie and Penny Smythe.

1. D.H. Akenson, The Irish Diaspora: A Primer (P.D. Meany, Toronto and Institute of Irish Studies Queen's University, Belfast, 1993), pp 132-133.

2. See D.P. McCracken, "A Commentary on Sources for Ireland-South African History and a Select Bibliography", in D.P. McCracken (ed.), Essays and Source Material on Southern African-Irish History, Southern African-Irish Studies, 4 (University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, 2012), pp 176-188.

3. J.B. Brain, The Cape Diary of Bishop Patrick Raymond Griffith from the Years 1837 to 1839 (Southern African Catholic Bishops' Conference, Cape Town, 1988).

4. K.W. Smith, Alfred Aylward: The Tireless Agitator (AD Donker, Johannesburg, 1983); and J.L. McCracken, New Light at the Cape of Good Hope: William Porter the Father of Cape Liberalism (Ulster Historical Foundation, Belfast, 1993).

5. R.H. Henderson, An Ulsterman in Africa (Unie-Volkspers, Cape Town, 1944 and 1945).

6. S. Monick, Shamrock and Springbok: The Irish Impact on South African Military History 1689-1914 (South African Irish Regimental Association, Johannesburg, 1989).

7. D.P. McCracken, Forgotten Protest: Ireland and the Anglo-Boer War (Ulster Historical Foundation, Belfast, 2003); D.P. McCracken, MacBride's Brigade: Irish Commandos in the Anglo-Boer War (Four Courts Press, Dublin, 1999); and C. van Onselen, Masked Raiders: Irish Banditry in Southern Africa, 1880-1899 (Zebra Press, Cape Town, 2010).

8. G.B. Dickason, Irish Settlers to the Cape: A History of the Clanwilliam 1820 Settlers from Cork Harbour (A.A. Balkema, Cape Town, 1973).

9. B. Ronan, Forty South African Years: Journalist, Political, Social, Theatrical and Pioneering (H. Cranton, London, 1919).

10. P.A. McCracken, "Shaping the Times: Irish Journalists in Southern Africa", Southern African-Irish Studies, 2, 1992, pp 140-162.

11. See for example, T. Foley and F. Bateman (eds), Irish-Australian Studies: Papers Delivered at the Ninth Irish-Australian Conference in Galway, April 1997 (Crossing Press, Sydney, 2000); C.J. Houston and W.J. Smith (eds), Irish Emigration and Canadian Settlement (University of Toronto Press and Ulster Historical Foundation, Belfast, 1991); and N. Kapur, The Irish Raj (Greystones Press, Antrim, 1997).

12. McCracken, MacBride's Brigade; K. Jeffery, "The Irish Soldier in the Boer War", in J. Gooch (ed.), The Boer War: Direction, Experience and Image (Frank Cass, London, 2000), pp 141-151; and Monick, Shamrock and Springbok.

13. Akenson, The Irish Diaspora, chapter 5. See also D.H. Akenson, Occasional Papers on the Irish in South Africa (Institute of Social and Economic Research, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, 1991); Dickason, Irish Settlers to the Cape; D.P. McCracken, South Africa's Irish Heritage, 1787-2007 (South African Heritage Council, Pretoria, 2008); and Van Onselen, Masked Raiders.

14. D.P. McCracken, "Irish Settlement and Identity in South Africa before 1910", Irish Historical Studies, 28, 110, November 1992, pp 134-49; D.P. McCracken, "Odd Man out: The South African Experience", in A. Bielenberg (ed.), The Irish Diaspora (Longman, Harrow, 2000), pp 251-271; and D.P. McCracken (ed.) Southern African- Irish Studies, 1 (1990), 2 (1992), 3 (1996) and 4 (2012).

15. Henderson, An Ulsterman in Africa; and N.D. Southey, "Dogged Entrepreneurs: Some Prominent Irish Retailers", Southern African-Irish Studies, 2, 1992, pp 163-179.

16. H.W.J. Picard, Lords of Stalplein (H.A.U.M., Cape Town, 1974), p 59.

17. For a detailed study of individual Irish journalists in South Africa, see P.A. McCracken, "Shaping the Times", pp 140-162.

18. D.H. Akenson, "The National System Established, 1831", in W.E. Vaughan (ed), Ireland under the Union, 1, 1801-70. A New History of Ireland, 5 (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1989), pp 530-535.

19. P. Maume, "Douglas Hyde", Dictionary of Irish Biography, 4 (Royal Irish Academy and Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp 879-883.

20. D.P. McCracken, "The Colonial Irish Conundrum", in M.N. Harris (ed.), Global Encounters: European Identities (Pisa University Press, Pisa, 2010), pp 189-197.

21. F. McGarry and J. McConnell (eds), The Black Hand of Republicanism (Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 2009).

22. P.A. McCracken, "Shaping the Times", p 140.

23. The Republic, 23 April 1921.

24. G. Shaw, The Cape Times: An Informal History (David Philip, Cape Town, 1999), chapter 1.

25. See P.A. McCracken, "Arthur Griffith's South African Sabbatical", and P.A. McCracken, "The Quest for the Middelburg Courant', Southern African-Irish Studies, 3, 1996, pp 227-262 and 282-289.

26. Ronan, Forty South African Years, p 221.

27. Ronan, Forty South African Years, p 180.

28. Supplement to the Standard and Transvaal Mining Chronicle, 19 March 1887.

29. Standard and Diggers' News, 28 September and 10 October 1899, quoted in T.K. Daniel, "Faith and Stepfatherland: Irish South African Networks in the Cape Colony and Natal, 1871-1914, and the Home Rule Movement in Ireland", in D.P. McCracken, The Irish in Southern Africa, 1795-1910, Southern African-Irish Studies, 2 (1992), pp 82-83.

30. D.P. McCracken, "Alfred Aylward: Fenian Editor of the Natal Witness", Journal of Natal and Zulu History, 4, 1981, pp 49-61. Ironically, given his tendency for wayward behaviour, Aylward published an interesting book, The Transvaal of To day. War, Witchcraft, Sport and Spoils in South Africa (William Blackwood, Edinburgh, 1878).

31. Privately published in Cape Town in 1920. Ella Nicholson died in June 1921.

32. D.P. McCracken, "The Irish Republican Association of South Africa, 1920-2", Southern African-Irish Studies, 3, 1996, pp 46-66. See also J. Atkinson, "Benjamin Farrington: Cape Town and the Shaping of a Public Intellectual", South African Historical Journal, 62, 4, 2010, pp 671-692.

33. Dictionary of South African Biography (HSRC, Cape Town, 1976), 3, pp 235-236.

34. Dictionary of South African Biography, 4, pp 568-569; and Cape Times, 25 November 1967.

35. D.P. McCracken, "The Marabou and the Rat Pack: British Military Intelligence and Correspondents in the South African War of 1899 to 1902", International Association of Media and Communication Research conference paper, Istanbul, July 2011.

36. G. Storey, Reuter's Century, 1851-1951 (Max Parrish, New York, 1969), pp 128 132.

37. Quoted in McCracken, MacBride's Brigade, p 93.

38. B. Hourican, "Edmund O'Donovan" and 'Frank le Poer Power", Dictionary of Irish Biography, 7, pp 413-415 and 8, pp 254-256.

39. D.P. McCracken, "From Paris to Paris, via Pretoria: Arthur Lynch at War", Études Irlandaises, 28, 1, 2003, pp 125-142.

40. Ronan, Forty South African Years, p 224. [ Links ]