Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Historia

versión On-line ISSN 2309-8392

versión impresa ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.57 no.2 Durban ene. 2012

ARTICLES ARTIKELS

Zimbabwe's land struggles and land rights in historical perspective: The case of Gowe-Sanyati irrigation (1950-2000)

Mark Nyandoro

PhD degree (UP) and is a research associate in the Research Niche for the Cultural Dynamics of Water (CuDyWat), NorthWest University (Vaal Triangle Campus), Vanderbijlpark. He is a lecturer in Economic History in the Department of Economic History, University of Zimbabwe

ABSTRACT

This article examines the history of land struggles in the Sanyatidryland and the Gowe-ARDA irrigation-community in northwestern Zimbabwe from 1950 to 2000. Land has been one of the most contentious issues in this area in the colonial and post-independence eras. Informed by the broader contestation around land, the article seeks to address the question of indigenous rights to land in Zimbabwe. Writing from an economic history point of view, it analyses the historical roots of contemporary land struggles and land grabbing in Zimbabwe since the forced removal of people from Rhodesdale to Sanyati in 1950. It also evaluates the need for land (as a factor of accumulation) and water rights in addressing key issues that could enable Zimbabwe realise peace and the much-needed restoration of the economy. Demands for land and associated rights are an indicator of the tension reminiscent of the dryland and ARDA-irrigated lands in Sanyati which was informed by Rhodesian-era evictions and resettlements. Clearly, in the pre-2000 period, the lack of adequate land to settle the farmers on a satisfactory basis coupled with the absence of a deliberate policy framework to regularise land-allocation has created a perception of economic disempowerment in both the dryland and irrigated peasant-sectors of the Zimbabwean economy. This informs the spate of farm-invasions witnessed in recent times in Gowe-Sanyati and beyond and underlines the fact that it is imperative that further research be undertaken on Zimbabwe's contemporary agrarian revolution.

Keywords: Gowe-Sanyati; dryland and irrigation agricultural development; land rights; land tenure; land acts; land reform; water resources; human rights, land invasion.

OPSONINIING

Hierdie voordrag ondersoek die geskiedenis van grondstryd in die Sanyati-droogland en die Gowe-ARDA-besproeiingsgemeenskap in noordwes-Zimbabwe van 1950 tot 2000. Grond was nog altyd een van die mees omstrede kwessies in hierdie omgewing in die koloniale en die post-onafhanklikheidsera. Geinspireer deur die breér stryd rakende grond, beoog die voordrag om die vraag rakende inheemse regte op grond in Zimbabwe onder die loep te neem. Deur primêre bronne aan te wend, insluitend mondelinge onderhoude (wat oorspronklikheid aan my artikel verleen), asook sekondere literatuur en deur vanuit 'n ekonomies historiese uitganspunt te skryf, analiseer die voordrag die historiese wortels van kontemporere grondstryd en grondinpalming in Zimbabwe sedert die gedwonge verwydering van mense uit Rhodesdale na Sanyati in 1950. Dit evalueer ook die behoefte aan land (as 'n akkumulasiefaktor) en waterregte om sleutelkwessies wat Simbabwe in staat sou kon stel om vrede en die hoogs noodsaaklike herstel van die ekonomie te ondervang. Deur die grondvraag as 'n omstrede kwessie van Zimbabwier-geskiedenis na te vors verbreed duidelik ons begrip van die kwessie. Terselfdertyd kan nuwe lewe in die voosgeslane of mankoliekige ekonomie ingeblaas word, gebaseer, onder andere, op grondaangeleenthede en uitdagings met die breer ontwikkelingsagenda en demokratiseringsproses te inkorporeer. Dit vereis dat verskeie belanghebbendes hulle moet losmaak van geykte houdings en weerstand teen 'n benadering wat op regte gebaseer is en een volg wat op grondhervorming toegespits is. Inheemse mense se demokratiese regte op grond en toegang tot water is van die allergrootste belang in n land waar koloniale staatsbeleide stryd en konflik oor grond geskep het. Eise vir grond en gepaardgaande regte is n aanduiding van die spanning wat herinner aan die droogland- en ARDA-besproeide grond in Sanyati wat geskep is deur Rhodesie-era-uitsettings en -hervestigings. Die ontneming van grond van die kleinboerestand in die pre-onafhanklikheidsera het aansienlik bygedra tot sosio-ekonomiese en politieke spanning. Die kennelike mislukking van die post-onafhanklikheidsregering om landhonger onder die mense te ondervang het ook gelei tot n verwagtingskrisis ("crisis of expectations") onder diegene wat gemeen het dat die terminering van die koloniale bewind op groter toegang tot grond sou uitloop. Duidelik, in die pre-2000-periode, het die gebrek aan voldoende grond om die boere op n bevredigende grondslag te vestig, gepaard met die afwesigheid van 'n oorwoe beleidsraamwerk om grondtoekennings te regulariseer het 'n persepsie van ekonomiese ontmagtiging in sowel die droogland- as besproeide kleinboerestand-sektore van die Zimbabwier-ekonomie geskep. Dit lei tot die stortvloed van plaasinvalle wat in onlangse tye in Gowe-Sanyati en verder aan waargeneem is en die noodsaaklikheid van verdere navorsing oor Zimbabwe se hedendaagse grondbesittersrevolusie.

Sleutelwoorde: Gowe-Sanyati; droogland en besproeiingslandbou-ontwikkeling; grondregte; grondbesitreg; grondwette; grondhervorming; waterbronne; uitsetting; stryd; konflik; menseregte; grondinvalle.

Background to land struggles: A historiographical review

Land struggles have not only characterised the history of Sanyati (a frontier region), but also that of Zimbabwe since British colonisation in 1890. The late twentieth century witnessed intensified competition to acquire land by several groups who were growing increasingly impatient over the slow pace at which land reform1 was being implemented after independence in 1980. Much of the move towards land reform has been mobilised, but some of it has been spontaneous. It would seem that from the 1950s to the 1990s there was more spontaneity than mobilisation. However, from 2000 onwards the mobilisation process was accelerated because the ruling party's rallying campaign became land, whereas the opposition preferred to remain silent on the land clause included in the proposed new constitution. Indeed, the mobilisation for "land grabs" became largely political and was perceived in many circles as disrupting law and order in the country.

Peace and reconstruction in Zimbabwe will definitely be premised on a sustainable solution to the clamour for land and water rights. With the international community (led by the former colonial power, Britain, and the USA) advocating a Western-brokered solution to the land question, President Mugabe and other African leaders are pushing for a Zimbabwean-oriented or at least an African Union (AU) or Southern African Development Community (SADC)-led solution to the issue. They are doing so under the now popular dictum of "African solutions to African problems".2 The control of land and water resources is also perceived as a key aspect of efforts to achieve a peaceful solution to the economic problems that have beset the country since the 1990s. Conflict over land and challenges posed by a malfunctioning economy continue to threaten stability in Zimbabwe. Hence, from the late 1990s to 2000 and beyond, Zimbabwe has increasingly advocated for "African solutions to African problems" as part of attempts to prevent the West from meddling in what this southern African nation sees as its domestic affairs, including land, socio-economic and political development.

Potentially, Zimbabwe's deeply contested land reform process was intended to right the wrongs of the past. It was felt it could be settled collectively following the historic signing of the Unity Pact on 15 September 2008 whose rallying point - "an African solution to an African problem" sets the tone for future conflict resolution on the continent. Land pressure and the unrest that has accompanied it should be treated as a matter of urgency not only in Zimbabwe but throughout the southern African region. The massive transfer of land to those who, for many years have been deprived of this resource calls for a major rethinking of the process of land reform on the African continent.3 In many parts of Africa, it should be realised that land is socially embedded; it is a site of complex and interlocking tenurial rights.4

Although struggles over rights to individually or collectively held plots existed in pre-colonial times these were intensified during the colonial period mainly because customary tenure was being rewritten and sometimes re-invented. Colonial authorities erroneously assumed that the European concept of proprietary ownership covered the full range of customary land-rights in Africa.5 This was a gross misjudgement of the situation and its implications have been enormous among many indigenous groups who have subsequently resorted to both open and surreptitious means of laying claim to land. The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations (UN) has observed that the problem of absolute or near landlessness in many rural communities in Africa (also in Asia and Latin America) has become increasingly acute since the mid-1980s.6

This article explores the trends that culminated in the 2000 land seizures in Zimbabwe. It contends that conflicts over land distribution were informed not by developments from the turn of the new millennium, but by earlier events which are the embodiment of a very complex history on the issue of land in both colonial and post-colonial Zimbabwe. Putting disputes and struggles over land into a broader national and historical perspective will help to shed light on the origins of a process that transcends some recent analyses of the land question in this former British colony. Sufficient evidence exists in the historiography of Zimbabwean land policy to show that the quest for land and attendant rights pre-dated the 2000 agrarian reforms (the redistribution of public and private agricultural lands, regardless of produce and tenurial arrangements, to landless farmers and regular farm workers)7 in the country.

Studies of land struggles in Zimbabwe have been conducted by several scholars such as S. Moyo, V.E.M. Machingaidze, M. Rukuni, C.K. Eicher, M. Colchester and L. Lohmann.8 However, some of these studies have not established a firm link between colonial conflicts over land and the contemporary wave of land invasions. Furthermore, these works have focused primarily on disputes over dryland and have neglected the investigation of conflicts over Agricultural and Rural Development Authority (ARDA)9 irrigated farmland. This article seeks to fill this gap by examining land struggles in both the dryland and irrigated rural settings of Zimbabwe. In the former, conflicts have usually emerged on the basis of differential land holdings, but in the case of irrigated farmland, the ability to pay the water rate and land rent, and the sheer audacity of individual plotholders who dare to access vacant irrigation plots, often determines the nature of land struggles. This article attempts to foster innovative ways of conceiving "land grabbing" through a systematic analysis that captures the diversity, complexity and controversy of this phenomenon. Gowe-Sanyati has been selected as a valuable test case for the study of unique and differential forms of land struggles in a frontier region of Zimbabwe. The article focuses specifically on Sanyati in relation to the wider literature, and adds a new and different dimension to existing knowledge in the field.

For example, N. Amin addresses Zimbabwe's politics of land and state-making since independence,10 but an analysis of the intricate relationship between colonial and post-colonial demands for land is sometimes glossed over. Literature that sufficiently contextualises post-independence agrarian and development policies and their changing nature has been published by S. Moyo, J. Herbst, L. Tshuma and J. Alexander, among others.11 Moyo acknowledges that the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF)12 government initiated radical and substantial socio-economic changes in land reform processes in the post-independence era, but he does not dwell much on whether the 2000 and preceding land invasions were instigated by ZANU-PF or were a bi-product of non-mobilised peasant agency. Herbst focuses, inter alia, on the new black government's efforts to resettle black farmers on formerly white-owned land, including which groups were the main beneficiaries of that land. The extensive coverage and critical analysis of agrarian transformation, state institutions and interest groups is vital. Herbst glosses over clamours for land and associated land-allocative processes in ARDA-type irrigation settlements.

Tshuma gives a plausible explanation of how customary tenure vested title to land in the colonial state, hence facilitating administrative control of rural society. Basically, institutionalised customary tenure was deemed to be communal and excluded individual rights. Tshuma points out that on the contrary, customary tenure was dynamic and recognised individual use rights whilst at the same time facilitating accumulation and differentiation. In the post-independence period it continues to be dynamic. Nevertheless, ARDA irrigation tenants or outgrowers,13 who depend on the Munyati River for water, have consistently been deprived of customary rights to land by the lease agreement which has not been revised since 1967. In that year, the Ministry of Internal Affairs (responsible, inter alia, for agricultural development) required all plotholders in Southern Rhodesia, including those at Gowe (a smallholder irrigation scheme adjacent to the Main ARDA Estate in Sanyati which served as its major source of labour), to enter into an agreement of lease, but the agreement did not give ARDA settler farmers security of tenure.14

Alexander's paper focuses on a case study of land redistribution15 in the Insiza District of Matabeleland - a process which was basically neglected save for the abrupt encroachments by cattle owners under severe pressure from drought to gain access to neighbouring ranch lands. Similar encroachments were experienced in Sanyati where the ARDA core estate has been repeatedly invaded by land hungry Gowe irrigation tenants and their dryland counterparts especially from the 1990s onwards. Nonetheless, whatever forms of land seizure occurred in Matabeleland were predominantly based on livestock production and not dryland and irrigated cropping as the case in Sanyati and other parts of Zimbabwe's savannah woodland. For M. Nyandoro (who is mainly writing this paper from an economic history orientation) the quest for more land, though, has been a common phenomenon throughout the colonial period as it continues to be a major post-independence issue.16

The year 2000 is inappropriate to benchmark land redistribution and broad agrarian reform in Zimbabwe

The year 2000 (as is often the case) should not be used as the major benchmark in land redistribution and land reform discourse in Zimbabwe. Indeed this year saw the further intensification of historically-steeped struggles to own land. The sources referred to in this paper and others reveal that a huge amount of evidence exists on the origins of clamours for land by the indigenous population of Zimbabwe. A.S. Mlambo and I. Phimister point out that after 1890, when the hoped-for mineral discoveries proved disappointing, many of colonial Zimbabwe's white settlers turned to agriculture.17 This apparently marked the beginning of loss of land ownership rights by many African farmers. From 1890, under the British South Africa Company (BSAC) administration, Africans were dispossessed of their right to own prime agricultural land and water two very vital and contentious natural resources. According to C. van Onselen, this loss of their land was accompanied by a great deal of desperation on the part of people who were trying to eke out a living and were burdened by forced taxation. Since 189418 the need to raise money for various forms of tax, ranging from hut, dog, cattle and poll taxes grew more pressing. These taxes were primarily instituted to procure African labour for European-owned enterprises and succeeded in forcing many landless people from the newly created, infertile and inhospitable "reserves" to search for work on white-owned farms and on the mines.19 The situation was exacerbated in the 1920s when a number of African applicants in dire need of land were denied permission to buy land by the director of Land Settlement on the grounds that African ownership would depreciate the value of adjacent European land.20 The white settlers also feared that the relatively small-scale purchases of land by the Africans, which had taken place by 1921, was merely the first indication of what would become a massive influx of advanced Africans into the so-called European area. This led to the appointment of the Morris Carter Commission (or the Lands Commission of 1925), which was set up to test opinions on the question of land segregation in the then Southern Rhodesia. This succinctly enunciated European fears of the "inevitable racial conflict" which would ensue unless a policy of land segregation was adopted in all haste.21

The Land Apportionment Bill, which was the outcome of the Carter Commission's report, became law in 1930 as the Land Apportionment Act (LAA) an Act which certainly stirred up antagonism and conflict because of the displacement and dispossession it engendered. Although the law did not take effect until April 1931, under the terms of the new Act, the rights of the Africans to land ownership anywhere in the colony were rescinded.22 Africans were only compensated for this loss by being given the exclusive right to purchase land in the so-called Native Purchase Area (NPA); otherwise they could move outright to what were then known as the native reserves (now communal areas).23

This partly explains why Chief Wozhele was moved from Rhodesdale24 to Sanyati under the Native Land Husbandry Act (NLHA)25 of 1950/51, after acts of arson. Enforcing this removal also reinforced the relationship between "land grabbing" and migration. The Europeans intended to set aside Rhodesdale for their occupation and push the African population further out of this "white enclave". This illustrates that the exploitation of land and other natural resources in Zimbabwe has gone through distinct epochs that have left a profound impact on land tenure and land rights. As already noted, the quest for bigger farmlands reached its height with the passage of the LAA and the NLHA which culminated in the forced removal of African farmers from their original agrohabitats. These notorious pieces of legislation heightened farmland acquisition by white settlers in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and left in their wake a gruesome legacy of land and resource conflicts arising from loss of control over land and natural resources such as water. Such laws set the tone for the unprecedented countrywide rush for farmland ("land grabs") by many smallholder peasants and indigenous communities in the post-independence period. In turn, the discourse on this unique moment in history has been stimulated. White farmland acquisitions, on the one hand, and the inability of the new national government to resolve the land shortage, on the other, have raised a litany of human rights-related concerns on the fate of millions of impoverished peasants in Zimbabwe. Rural populations in particular now have diminished access to land and water resources (largely because of evictions) and local food production has been seriously undermined.

The process of evicting Africans from their land was intensified by the passage of the Land Tenure Act in 1969. Land dispossession coupled with racial discrimination and other colonial injustices led to the outbreak of the Second Chimurenga/Umvukela (19661979).26 For Kriger, the roots of the liberation struggle were steeped in land. During the war and with the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in 1965, Ian Douglas Smith (the then prime minister of Rhodesia) tried to appease Africans who had been disgruntled by being forcibly moved to infertile pieces of land by both the NLHA and the Land Tenure Act, by setting up irrigation projects in their areas.27 It was against this backdrop that the Gowe Pilot Smallholder Irrigation Scheme and the Tribal Trust Land Development Corporation (TILCOR) Sanyati Core Estate were established by the colonial government in September 1967 and March 1974 respectively. The war ended with the signing of the Lancaster House Agreement in 1979. Once the war was over, the government of independent Zimbabwe showed its commitment to addressing land disparities by embarking on resettlement programmes across the country.

The first phase of Zimbabwe's land reform process commenced in the early 1980s when government acquired over 65 percent of the 3,6 million hectares transferred to poor families by 1997.28 Most of these land transfers took place in a context of land occupations by peasants, especially in the Eastern Highlands from 1980 to 1985.29

The activities of this period marked the relocation of people to what were known as "minda mirefu" (long or big fields that had been bought by the government for resettlement).30 This resettling of people was, however, not accepted without resistance by some urban and rural dwellers targeted to be relocated to "minda mirefu" in the 1980s which resulted in government compulsorily making people give up their original homes and go to the newly created farms. With the government aiming at decongesting the major urban centres where squatter camps had proliferated, the most notable resistance came from these areas. The "minda mirefu" model of economic development adopted after independence faced intense opposition from a disgruntled populace largely because it lacked prudent planning. The government did not provide essential infrastructure such as roads, schools and clinics for African farmers willing to move from the congested areas to the new large farms.31 It can also be noted that, although the term "minda mirefu" implied abundant land, the reality was that each household was only allotted five hectares of arable land;32 this was a pittance considering the land requirements of the intended beneficiaries of the programme and subsequently the land needs of their offspring in an increasingly commercialising environment. The latter's demand for land meant subdivision of already small plots into minute portions. Under the circumstances, there was "entrenched resistance" to the "minda mirefu" concept by both urban and rural dwellers, in many ways this typified the resistance of their forefathers to forcible removal from Rhodesdale and other such districts designated as white areas.

As indicated above, it was mainly the people in informal squatter areas in the towns who were relocated. The squatter camps were a reflection of the lack of land on which to build decent shelters and practise peri-urban agriculture. However, the development of squatter camps cannot be explained solely by land shortage. It is a challenge that is also steeped in the massive rural-to-urban drift particularly after independence, with people searching for employment opportunities, sustenance and decent livelihoods. Improved livelihoods were perceived to be the hallmark of big cities such as Harare, Chitungwiza and Bulawayo in the post-liberation era, due to their relatively higher standard of living compared to the rural areas. Ultimately, these squatter occupations were regularised into official allocation through the accelerated land resettlement programme whose legal basis was the 1985 Land Acquisition Act.33 Under this programme, the government of Zimbabwe budget allocations and a British government disbursement of £37 million were availed for "land acquisition and settler emplacement".34 The phase ended in 1987 with a policy review that led to the adoption of the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP) in 1990/1991.

However, instead of leading to an increase in the amount of land distributed to those who needed farming space, the ESAP market-oriented reforms had the opposite effect it reduced the amount of land. This prompted the government to pass the Land Acquisition Act of 1992 which was designed to legalise land redistribution and to eliminate the strictures imposed on land acquisition by the Lancaster House Agreement. The Act was succeeded by the Rukuni Commission/Report of 1994, which was set up to investigate the best way of approaching land reform in Zimbabwe. It recommended redistributing land on the basis of the expectations of the community (emphasising a participatory approach) and on the basis of avoiding similar disparities in land distribution as had occurred in colonial times.35 Such an approach, it was felt, would have the effect of creating even more landlessness and a wider gap between rich and poor. Unfortunately, the Rukuni Report was not made widely available in the early days. Furthermore, its recommendations were not taken seriously until land reforms assumed a more radical nature from 2000 onwards.

The second phase of Zimbabwe's land reform process fell largely within the ESAP period and was characterised by limited land acquisition and redistribution, leading to the emergence of Churu farm36 and other informal settlements in the 1990s. There was a great deal of controversy around Churu farm, owned by the late Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) nationalist, Ndabaningi Sithole. Realising that people in urban areas wanted land, Sithole seized the opportunity to resettle his supporters on his farm. However, they were forcibly removed by the government. The police, acting on government orders, were also deployed to remove people from other informal settlements that had emerged in the Chipinge area of Manicaland Province.

Between 1980 and 1997 the dominant land acquisition approach was a state-centred, market-assisted approach in which land was purchased by the state for redistribution on a willing-buyer/willing-seller basis in line with the Lancaster House Agreement.37 The private sector identified the land available for resettlement while the central government purchased the land on offer. In turn, the government provided land to beneficiaries selected mainly by district officials

under the supervision of central government officials.38 However, over 70 percent of the land acquired for resettlement on the market tended to be in agro-ecologically marginal areas located mainly in four southern provinces of the country.39 This left much of the prime land in the three Mashonaland provinces untouched. Thus, the amount, quality, location and price of land acquired for redistribution was driven by landholders. It was neither the government, as driver of the land acquisition policy, nor the intended beneficiaries, who controlled the process.40

The third period of Zimbabwean land reform began in 1997 with the designation of 1 471 commercial farms for possible acquisition. Approximately 804 farms were de-listed because the government, donors and large-scale farmers were involved in negotiation.41 This led to an international donors' conference or fact-finding mission in September 1998 at which the "inception phase framework plan" was adopted in the aftermath of the Chief Svosve land demands in the Marondera area.42 This marked the start of what became known as the Jambanja phase (violent seizure of white-owned commercial farmland) of the land redistribution exercise following the occupation on 18 June 1998 of Igava, Daskop, Nurenzi and Eirene farms by Chief Svosve's people drawn mainly from Mupazviriyo, Nyamunyamu and Muchakata villages.43 Thus, by the time the state decided to seize all commercial farmland in 2000, the Svosve villagers living about 90km outside the capital had become involved in a relatively non-mobilised and highly unprecedented stunt, taking the lead at the forefront of the farm occupations. Because of the commotion around the Svosve people's land struggles, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) organised a conference in Harare to discuss the incident and the best way of resolving the land issue peaceably.44 However, under this plan the government acquired less than 250 000 hectares of land for resettlement.45 This was clearly inadequate; hence another wave of spontaneous land occupations was initiated by the belligerent Svosve community in 1999.46 They independently and unilaterally occupied farms vacated by white farmers and refused to submit to the police who tried to persuade them to leave. The government eventually managed to suppress these farm onslaughts.

In government circles, a policy shift in the land redistributive agenda occurred in the aftermath of the attempts by Chief Svosve's people to seize land. Earlier, it was envisaged that the land question would be resolved by constitutional means, but in 2000 the government embarked on a series of controversial and often violent, fast-track "land grabs". The radical agrarian reforms in 2000 were an opportunity for the opposition party the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), which had been formed two years earlier, and their allies in the National Constitutional Assembly (NCA) to denounce the process. The proposed constitutional referendum47 of 2000 was used by the opposition as a campaign tool against "land grabbing". Nevertheless, while it is true that issues of land were central to the constitutional referendum of 2000, the politics surrounding the continued rule of 2002).

President Mugabe was also a key issue leading to the historic "No" vote to the Chidyausiku Draft Constitution which was discarded by the nation on 13 February 2000. For Takura Zhangazha, the "No" vote "was the most serious non-partisan indictment of a sitting government since Zimbabwe's independence in 1980".48 The result of the referendum was, however, greatly influenced by a number of external factors, namely the antagonism of Western governments and financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), whose hostility to President Mugabe's reign was growing.49 As far as the question of land was concerned clearly, the opposition's meeting point was the land clause embodied in the draft constitution. Thus, the proposed new constitution which included a land re-distribution clause, was subsequently rejected. Impatient war veterans (under their charismatic leader, Chenjerai Hunzvi) and a horde of other ZANU-PF supporters went ahead to take white-operated farms.

The government of Zimbabwe was by now fully aware of the citizens' growing impatience over land allocation and from 2000 onwards embarked on the fourth phase of land reform with minimal collaboration with its negotiating donor and commercial farmer partners. Radicals in ZANU-PF had decided it was time for the government to "go it alone" and embark on massive compulsory land acquisition.50 Although negotiation and dialogue continued it was, however, intermittent in nature. Despite the fact that by August 2000 over 3 000 farms had been targeted for compulsory acquisition, less than 30 farms totalling 60 000 ha had been acquired through compulsory methods.51 Over 95 percent of all redistributed land was acquired through markets. Of this, over 60 percent of the land acquisition costs were paid for by the government.52 This period saw fiscal deficits escalating to very high levels and a growing economic crisis, which was accompanied by increasingly aggressive demands for land redistribution. These demands have recurred in one form or another since 2000 and are now threatening to become a major contributor to economic and social instability in the second decade of the new millennium.

Following the 2000 land invasions, other groups of people occupied Porta Farm, just 40 km outside Harare. They too were not spared from government action either. This time they were ruthlessly (rather than persuasively) evicted. Notwithstanding a high court ruling in July 2005 that the government was not supposed to evict or demolish the "makeshift" structures at the farm until and unless it found alternative accommodation for these people, this was not to be. Bulldozers were sent to Porta Farm, and they razed everything to the ground. The police remained adamant that the court judgement did not apply to them, maintaining: we are "not run by the courts". This determination by government to discourage unilateral action, though, did not terminate the people's long-standing desire to own at least a piece of land in independent Zimbabwe. It also seriously lacked resonance with how Hunzvi and his group had been treated (they were not forcibly removed), thereby revealing the government's intolerance to action taken by opposition political ranks. It seemed that generally speaking, the government was closing its eyes to land invasions and the people of Gowe-Sanyati in north-western Zimbabwe decided to join the fray.

Clamours for land and property rights in north-western Zimbabwe: A brief synopsis

For many years, clamours for land and concomitant rights have dominated not only the history of Gowe-Sanyati in the northwest, but also that of Zimbabwe more generally. It has been as much a tussle for land as a struggle for a rights-grounded resolution to the land crisis. For instance, there is an ongoing debate about property rights and human rights but this tends to avoid mention of indigenous people's rights to land as a basic human right and where such rights derive from. In other words, the Zimbabwean case is not merely a struggle for land because it is also premised on rights.

Land grievances in Zimbabwe date back to the arrival of the Pioneer Column, a British unit, in 1890. The subsequent hoisting of the Union Jack by the British formalised immense land seizures in accordance with the agreements reached at the Berlin Colonial Conference of 188485. In this way, land was expropriated from the black people by means of a corrupt, undemocratic and unaccountable process. The nineteenth and twentieth- century struggles between the Africans and the settlers included the Anglo-Ndebele War (1893 94); the First Chimurenga/Umvukela (189697) and the Second Chimurenga. These conflicts were informed mainly by colonial land alienation policies implemented since the occupation of the then Southern Rhodesia and were intensified by the passage of the LAA in 1930, the NLHA (1950) and the Land Tenure Act of 1969. Fundamentally, these pieces of legislation, which were synonymous with the South African apartheid policy of separate development, significantly deprived indigenous inhabitants of prime agricultural land and increased insecurity of tenure. They thus became the cornerstone of African disgruntlement against settler rule, which did not abate until the Lancaster House Agreement signed in London in 1979 and Zimbabwean national independence the following year.

In the 1980s, the government of independent Zimbabwe implemented several resettlement programmes. As already indicated, in the early 1990s it passed the Land Acquisition Act and embarked on controversial agricultural reforms in 2000 as a way of addressing liberation struggle promises on land and correcting colonial imbalances in land distribution between the black and white population of the country. This detail is the contextual framework within which Sanyati land struggles should be understood.

In Sanyati, the ARDA smallholder irrigation farmers at Gowe in conjunction with their surrounding dryland counterparts have exhibited great anxiety over land allocation since the 1950s when most of them were forcibly removed from the Rhodesdale Estates in the Midlands Province under the NLHA. The dryland farmers were then settled in Sanyati on eight-acre holdings per family. Their quest for more land was not resolved when the Ministry of Internal Affairs established the Gowe Small-Scale Pilot Irrigation Scheme in 1967. In this scheme, incumbent plotholders who were selected on the basis of their master farmer skills53 were allocated a paltry two to four acres each. A direct consequence of their anxiety was the invasion of ARDA-Sanyati Main Estate land (discussed below) starting in 1992 a process that assumed phenomenal proportions in 2000 with the dramatic agrarian reforms of that year. The events of 2000 have set the tone for further land struggles in the country because certain sections of the local and international community have expressed their disenchantment not only with the manner in which the land has been parcelled out but also with the entire Zimbabwean state system. In the past this has led to clashes between the government and other stakeholders and similar outbursts are expected to continue in the future if the land issue remains unresolved.

A regional solution to the crisis besetting the country is possible if viable and sustainable alternative methods of addressing the land issue are made. Among other things, the intricate network of issues over land conflicts on other parts of SADC such as South Africa and the efficacy of the mediation role by South Africa should be taken into account. The implications of Zimbabwe's land struggles in the new millennium are therefore far-reaching in their scope and nature, not only for the country but for the entire sub-region. The case of the Sanyati frontier region bears testimony to this.

Colonial evictions and early land struggles: The Sanyati hinterland in the pre-irrigation phase

In the pre-colonial and early colonial times, Sanyati was not a very popular destination for land claimants because of its frontier location; its inhospitable temperatures, poor and predominantly sandy soils; and its problems of tsetse infestation. The area was originally inhabited by indigenous farming and hunting communities derogatorily referred to as the Shangwe.54 After the massive 1950 evictions of Africans who lived as "squatters"55 on the Rhodesdale Estates in the Midlands Province, Sanyati became inhabited by an assortment of both indigenous (Shangwe) and "immigrant" populations (Madheruka)56 who fall under the paramount chiefs Neuso and Wozhele respectively. The African evictees were targeted for forced resettlement in the sparsely populated frontier regions of Sanyati and Gokwe in the 1950s under the Native Land Husbandry Act.57 The year 1950 thus marked the beginning of repressive, fast-track removals of unprecedented magnitude for most of the people living on so-called Alienated and/or Crown Lands.

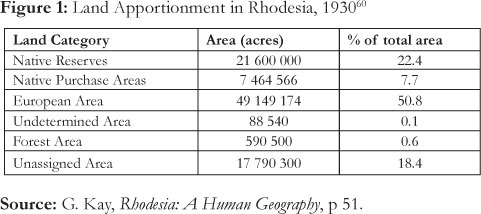

The immediate post-Second World War period ushered in what were arguably the three largest waves of "immigrants" into Sanyati; they were people who had been compulsorily removed from European and Crown land by the Rhodesian government of the time.58 Since Rhodesdale was a European ranching area, Chief Whozhele had to be moved to Sanyati one of the settlements designed for Africans. This was the culmination of an idea mooted prior to the granting of responsible government to Rhodesia in 1923, when the question of allocating separate defined areas in which Europeans and Africans could respectively and exclusively acquire land, had arisen in the Rhodesian legislature. It was the LAA which finally legalised the division of the country's land resources between black people and white people.59 This marked a major turning point in colonial Zimbabwe's racialised regime, which in all respects became highly segregationist in outlook. Figure 1) below illustrates the land categories into which the country was divided and the area in acres occupied by each category.

Source: G. Kay, Rhodesia: A Human Geography, p 51.

It should be noted that the influx of white immigrants from Europe in the post-war period necessitated the eviction of a large number of Africans from Crown and Alienated Lands. To make way for the new immigrants, recourse was made to the policy of eviction of Africans from land designated as Crown Land by the LAA, which, for security reasons lay somewhat dormant during the war years. The decade 1945-1955 saw at least 100 000 African squatters from all over the colony being moved, often forcibly, into overcrowded "reserves" and the inhospitable and tsetse fly-ridden Unassigned Areas.61 The first group from Rhodesdale was forcibly moved to Sanyati in 1950; the second was moved in 1951; the third and last wave arrived in Sanyati in 1953,62 the year of the Federation of Southern Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe), Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and Nyasaland (Malawi) was formed. These "immigrants" lived on European-designated land before their ruthless eviction and subsequent settlement in Sanyati. This backwater region of northwestern Zimbabwe was selected, among other reasons, for resettlement of the former Rhodesdalites because it was distinguished by the historical absence of competing claims by European settlers to land. In fact, as a malarial, tsetse-infested lowland, with patchy and variable rains averaging below 400mm per annum, white farmers considered it highly unsuitable for crop cultivation or animal husbandry.

Eventually, 356 families were accommodated on the 28 000 hectare Sanyati Reserve (now Sanyati communal land), each with an allocation of eight acres of arable land and ten head of cattle.63 The forced eviction of Africans from Crown Land to Sanyati Reserve under the NLHA meant that people were being moved from relatively bigger plots of 40 or more acres per farmer to much smaller pieces of land. The reality was that the Act attempted to scuttle the process of rural differentiation and African advancement by allocating the peasantry small and uneconomic land holdings. Overcrowding and erosion ultimately became serious problems. Numerous measures were adopted to deal with population pressure and improve the carrying capacity of the reserve with little by way of success. These included the implementation of the so-called centralisation policy (19501953)64 and the enforcement of conservationist measures such as contour ploughing and de-stocking. However, there was widespread opposition and resistance to these state measures carried out in accordance with the NLHA.

It is important to note that while the Act sought to equalise land holdings for the majority of rural households, it also created conditions for the emergence of a small class of large landholders. In Sanyati, these were among the many peasants who had challenged the eight-acre allocations per household. Given the very low rainfall in the area and the fact that it was not well endowed with fertile soils, the allocation of limited acreage per family was staunchly resisted. This size of land proved far too small to sustain a family and their animal possessions, nor was it sufficient to produce a saleable surplus as stipulated in the Act. Household land holdings in Sanyati was frankly unacceptable because the "reserve" was far smaller when compared to land-abundant Gokwe, where differential access to land is rife and many householders have access to as much as 100 acres of farmland.65 In the wake of land allocation under the NLHA, the Mangwende Commission of Inquiry of 1961 revealed that although some landholders cultivated ten or more acres, many households actually cultivated much less than the standard allocation of six to eight acres.66 In areas of excessive land pressure such as Sanyati the restricted size of arable lots per family is directly attributable to the scarcity of arable land. It was thus hardly surprising that in Sanyati, where far less land is available than in neighbouring Gokwe, that landless peasants or those with limited land were vying for more land.

An increase in population in Sanyati after the influx from Rhodesdale soon led to a sub-division of the initial allocated land for cultivation. Because sons of these "immigrant" farmers were not allocated land they simply encroached onto grazing areas held by others or self-allocated themselves land, thereby reducing the grazing areas. By 1960, for instance, the number of school leavers began to exceed the number of openings for work.67 The Rhodesian economy experienced an economic slump and many young men could not secure employment. Faced with unemployment in the towns, and the absence of adequate social security there, many young men were thrust back to the only form of security they knew a piece of land in the "reserves". Yet, they were denied that security68 because those who had left the rural areas to go to the towns prior to the initial allocations had "missed the boat" and were not considered for land allocations when they sought a few acres to eke out a living. Young men, just like their female counterparts, were considered minors and did not qualify for land allocation on that basis. Thus, according to the Native Commissioner (NC) for Gatooma, G.A. Barlow, land-rights were not given in Sanyati under the Land Husbandry Act to people who were not ploughing land in 1956 (when the Act was implemented) and those under the age of 21 years were ineligible to apply for land-rights under the Act.69 This meant that young land aspirants were deprived of land at a time when they sorely needed it.

Under these circumstances, it is no wonder that strong resentment to the Act stemmed from the younger generation who did not qualify for initial rights to land, and for whom there was no land available; they had no access to land rights at all. For the African nationalist groups, according to George Nyandoro, the secretary general of the Southern Rhodesian African National Congress (ANC), the NLHA "has been the best recruiter Congress has ever had", and the nationalists drew much of their support from young urban workers rendered landless by the Act.70 In fact, opposition to the Act was not confined to the landless young men; it was equally strong among rural accumulators who saw the Act as a constraint on their accumulation. These rural accumulators took over the leadership of rural opposition to the colonial administration. They joined the ANC and became some of its staunchest supporters. In the Makoni district, according to Ranger, the key leaders and opponents of the colonial administration in the aftermath of the NLHA were not landless young men, but members of the chiefly family, headmen and male peasant elders over 40 years.71 No matter how active the young men may have been in these nationalist parties, Ranger argues that the core of peasant radical nationalism in Makoni comprised the resident elders who were determined to retain their hold on their large plots of land.

Chief Wozhele of Sanyati, together with his royal lineage, were simply not prepared to give up their practice of overploughing because in Rhodesdale they had successfully cultivated fields of up to 40 acres which was five times the standard allocation in Sanyati. In an interview he confessed: "... people disliked the NLHA because they were used previously to a life of no control".72 Despite the strictures imposed by the Act, Ndaba Wozhele and his kinship group, Mudzingwa, Tiki, Vere, Sifo, Ngazimbi and Mazivanhanga, clung tenaciously to their extended plots of land and remained some of the largest land and cattle owners in the entire area.

It can also be argued that chiefly lineages and resident male elders resisted the NLHA because the Act rendered them powerless in the allocation of land. Previously they had held the cherished prerogative to distribute or redistribute land among their subjects; now this had been usurped. Norma Kriger notes that "loss of the right to allocate land so outraged chiefs in the early 1950s it looked as if they and the nationalists would forge a lasting alliance".73 Phimister similarly argues that:

alienated and embittered by the attempts of successive settler regimes to wrest control over the dynamics of rural accumulation from their grasp, a significant number of richer peasants turned away from cooperation with government agencies to embrace nationalist politics. It was the grievances and hopes of "the 30 percent better-off" African producers that crucially shaped both opposition to the NLHA and the kind of nationalism which emerged at the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s.74

It appears, therefore, that African nationalism in colonial Zimbabwe in the 1950s and early 1960s exhibited tendencies towards solidarity for a common cause between landless young men; elders and local leaders; and rural accumulators alike. This apparent solidarity across generational and class lines was intensified by the people's dislike of the NLHA. According to Holleman, the Act became one of the most contentious measures passed by the colonial parliament and was the target of bitter attack and resentment by the Africans. He argues that the Act faced extremely stiff opposition because it was "discriminatory and restrictive and agrarian and therefore became almost inevitably associated with the Land Apportionment Act, one of the most hated symbols of white authoritarianism and exclusiveness to the African".75

To demonstrate their disenchantment with the NLHA, a number of people in Sanyati who were bent on accumulation embarked on a process of self-allocating themselves land. In the circumstances, the NC for Gatooma (now Kadoma), under which Sanyati fell, was empowered by the then Ministry of Internal Affairs to prohibit the cultivation of any new lands in cases where all the suitable arable land had already been occupied. The Director of Native Agriculture, R.M. Davies, called for "strict control" and proceeded to say: "In terms of the Act [NLHA] every native who [was] cultivating land at the date of proclamation must be granted a farming right for land in that Reserve".76 What was worrying the administration was that Africans were extending their cultivation outside the original demarcated lands in a process called "madiro",77 especially above and below the contours, on stream banks, grass strips, vleis and even into streambeds. This led to serious erosion.

Madiro, or freedom ploughing was one of the various forms of manoeuvrings by which some farmers came to own larger pieces of land and larger herds of cattle than their counterparts. Most of the Madherukas ("immigrants") allocated themselves land and became employers of labour as they tried to further their accumulation prospects and establish more stabilised rural homes. Freedom ploughing which was the unilateral right peasants gave themselves to cultivate wherever they wished was quite widespread in Madiro Village (Ward 23), a community headed by Morgan Gazi. The village was given this name because of the massive land-grabbing that went on in defiance of NLHA stipulations. Most "reserve" entrepreneurs in this area cultivated up to fifteen acres. Gazi says that because he was a nephew of Chief Wozhele, he cultivated about eighteen acres,78 ten acres more than the standard allocation, illustrating how rife and uncontrollable madiro ploughing was, especially among people with chiefly connections. As a result, Davies observed: "The whole value of centralisation is nullified if there is not vigilance and control". He added, "It is the duty of Demonstrators and Land Development Officers to report any unauthorised encroachments to the Native Commissioner who can take effective action".79 However, encroachments continued, usually hidden from official view because there was a depleted staff of two demonstrators for Sanyati and this was insufficient to ensure adequate control.80 It can be noted that feverish attempts by African peasants to grab as much land as possible transcended the pre-irrigation period and persisted into the UDI era.

Sanyati irrigation agriculture during UDI

The inception of a pilot Smallholder Irrigation Scheme at Gowe in 1967, among other UDI policies, was designed to alleviate landhunger for the rural peasantry, particularly those with master farmer certification, most of whom were involved in cotton farming. Gowe-Sanyati agriculture from 1963 focused primarily on cotton production, but the cultivation of food crops such as maize, groundnuts, sorghum and rapoko was also encouraged. From 1967 onwards irrigated wheat and cotton were the chief crops. In the main, since the 1960s the growing of cotton (a drought resilient cash crop) introduced an element of commercialisation which intensified clamours for more land by the rural peasantry, not least resistance to the colonial cotton programmes. In this respect, the greatest justification for a case study of land struggles in an irrigation context compared to what happened in the dryland is the interesting contrast that emerges.

For instance, the advent of colonial rule did not cause much land conflicts in irrigation because this sectorwas still in its infancy. Since most of the schemes were introduced in low-altitude and low-rainfall areas, the initial justification for government aid to smallholder irrigation (up to the end of the 1920s) was famine relief or food security. However, following the amendment of the LAA in 1950 to become the NLHA, new irrigation projects were constructed as a means of absorbing the displaced African population from areas such as Rhodesdale. A report in 1950 by the Director of Irrigation for Southern Rhodesia indicates the dualism perceived by government between irrigation development and resettlement objectives in the post-war period:

It is a truism that only land which will support a dense rural population is flat, irrigable land. We have neither large areas of flat land nor unlimited water resources in this country, but to accommodate the growing native population every available acre will have to be put to maximum use. There are extensive dry areas particularly in the Southern and South-Western parts of the Colony where the only means of bringing land to proper use will be by large scale gravity, or where gravity is not possible, by large scale pumping. These schemes will be very costly, and by ordinary standards, uneconomic, but it may well be found that any other solution to the population problem will be still less economic and far more undesirable?81

Following this report, an Irrigation Policy Committee was set up in 1960 to examine the justification of irrigation as a means of settling black farmers.82 The recommendations of this committee, which were released in 1961, among other things noted that, "irrigation was not the best way of settling displaced farmers".83 In addition, the committee intimated that "the population pressure in black areas was temporary and would slacken as more found employment on white farms".84 However, reality on the ground in Sanyati shows that clamours for land were relentless and most African farmers desired to own their own piece of land (if not the dual ownership of both irrigation land and dryland) as retirement insurance.

This section of the paper, therefore, focuses on tussles for land that emerged in the Sanyati communal lands in the UDI era, particularly with the introduction of irrigation, because these struggles have not generated much scholarly attention. The irrigation era (the 1960s onwards) ushered in new and radical forms of stating claims to land. Irrigation plotholders were allocated standardised plots (plots of the same size) of up to four hectares, but these proved to be rather too small for what was perceived as an optimal holding, that is, ten hectares per farmer. It is this lack of adequate land which compelled enterprising smallholder irrigators to claim more land from the dryland areas a practice that was not permitted by government. However, whilst there was irrigation in Sanyati in the pre-colonial and early colonial times (comprising the watering of gardens using traditional methods) for sustainable food production, it did not cause significant land struggles. Irrigation's potential to attract new land claimants and particularly radical forms of struggle over land, appears to be a 1960s phenomenon in Sanyati.

The late 1960s saw the advent of irrigation and a new wave of people were encouraged to take up land as plotholders at Gowe. In some instances, smallholder irrigation schemes in colonial Zimbabwe were established to settle blacks displaced from land taken over by white farmers.85 The tenants on such schemes were not happy about the small size of the plots they were allocated. At Gowe, for example, each farmer was given between two and four hectares when they would have preferred ten ha (25 acres) or more.86 Irrigation has always had a clear political content because it embodies land and water, two of the most contentious issues in Zimbabwean history and one in which colonial injustice is very obvious. Due to land shortage, farmers always strove to acquire extra plots. A common feature of smallholder irrigation development in Zimbabwe is that irrigators tend to farm the dryland (rain-fed lands) as well. This practice is discouraged by government on the grounds that irrigation is intended to relieve land pressure on dryland resources and also that dryland activities depress the productivity of farmers on irrigated plots.

In fact, the Acting District Commissioner (DC) for Gatooma, D.K. Parkinson, threatened plotholders with eviction from the Gowe Scheme for refusal to accept advice from CONEX87 and for ownership of both a dryland and an irrigation plot. A man with land in both places was adjudged to be an unsatisfactory plotholder. The DC himself, R.L. Westcott the man who is credited with establishing the pilot Gowe Smallholder Irrigation Scheme in Sanyati spoke out strongly against the dual ownership of land on the part of the plotholders and the penalty for infringing this rule tended to be draconian. He made his stance very clear when he said:

Plots on irrigation schemes were not adjuncts to dry land holdings, but were intended to support families independent of any other resource ... there were many people without land, such as the sons of Purchase Area farmers, and the numbers were increasing at an alarming rate.88

Those allocated irrigation plots, but who, at the same time, had dryland holdings, were then warned by the DC that after two years (in some cases), and one year in others, they had to choose which type of farming they preferred.89 Considering the fact that this was one way for the plotholders to redress their land hunger and become wealthy rural "capitalists", Westcott's policy of ordering those still cultivating their dryland plots to leave Gowe was regarded as authoritarian. However, Westcott was adamant, arguing that if a tenant neglected his crops, or was careless in their cultivation, he was evicted on the basis of poor performance, which militated against achieving the scheme's long-term self-financing objectives.

Thus, the irrigators just like the dryland communal farmers in the surrounding area, used many inventing ways of accessing more land. Most peasant households involved in dryland and irrigation farming throughout the country were allocated approximately between three and ten acres of land by the colonial state under the Native Land Husbandry Act of 1951.90 In an attempt to survive and realising that land was a chief resource of production, at the time of independence in 1980, a handful of peasant farmers were utilising more than ten acres. Droves of others were frantically searching for land and many more, such as women and sons of both dryland and irrigation farmers were virtually landless. The few male farmers who were cultivating more than ten acres had manipulated the system of land allocation to have dual ownership of land. These farmers (mainly men) hoped to maximise their economic gain by the dual possession and cultivation of both dryland and irrigation holdings.

In colonial Zimbabwe, women were neither made recipients of agricultural loans nor controllers of the land which they spent so much time tending. At Gowe-Sanyati, they were generally not considered for plot allocation because of reasons related to the system of tenure applicable to ARDA schemes.91 Under the system instituted by the DC as well as that adopted under the ARDA lease agreement92 (leasehold tenure) a woman was assumed to have land once an allocation was made to her husband. This system was similar to the one applied to dryland agriculture where no women (or very few women) were allocated land in their own right. Weinrich has confirmed this by stating that most women had no land-rights in their own name.93 In this connection, while traditionally land was construed as an asset that belonged to all the people, Ruth Weiss's contention that men exercised almost monopolistic control over it is certainly true for Sanyati. Indeed, "Women worked the land, but had no say as to what should be planted or sold".94 Women berated this practice that deprived them of land ownership rights. Added to this, in Sanyati their male counterparts were constantly dissatisfied with their small plots, let alone another eviction (which was looming) for those who had occupied land that was designated for estate irrigation agriculture in the early 1970s.

Birth of Sanyati Main Irrigation Estate (1974): More evictions and loss of land

Since the forced evictions from Rhodesdale in the 1950s, Wozhele's people under headmen Mudzingwa and Dubugwane inhabited the area now occupied by the ARDA Main Irrigation Estate. They grew sorghum, rapoko, millet and groundnuts.95 These communities were later moved by the government to the adjoining lands of Dubugwane (under Wozhele) and Maviru (controlled by Neuso) because the land they had occupied previously was designated as an "irrigable area"96 and was now required by the Ministry of Internal Affairs for the establishment of a bigger irrigation scheme. Their community interests were not prioritised in the process.

In terms of the law, the relevant minister could appropriate all land or terminate any right of use or occupation over such land after serving the affected people with a written notice three months in advance, provided that those whose land was taken were compensated either with land elsewhere or with cash. The regulations also stated that any African who was in lawful occupation of an allotment on an irrigation scheme or who was permitted to occupy and use land in the irrigable area would be deemed by the district commissioner to be a probationer lessee in terms of sub-section (3) of section 9 of the Land Tenure Act.97 Although it is believed that there was consensus on the removal of people from the area designated for the core irrigation estate, there were some dissenting voices, notably Chief Neuso. Despite his reservations, the scheme was endorsed by his counterpart, Wozhele, for the benefits he envisaged the project would bring to Sanyati. Disgruntlement from some quarters was to define the not-so-cordial relationship between Gowe and the Estate since Gowe's takeover by TILCOR, that was going to run the pilot scheme in conjunction with their main scheme.98

The Main Scheme began operation in March 1974 under Alex Harvey as the estate manager. The TILCOR or ARDA compound which houses the Main Estate's permanent workers was named "Mudzingwa Village" after the headman who had paved way for this project. The Estate (1 000 ha in size), which was established with the aim of developing the surrounding communal area, included the Smallholder Settlement Scheme at Gowe, which was 120 hectares in size.99 Since the inception of both the smallholder component and the Main Estate, the tenants have always aired demands for more land. Many Sanyati residents actually joined the war that had the major objective of facilitating the release of substantial amounts of land for African use.

According to the first black TILCOR general manager, Robbie Mupawose, "The whole [agricultural] setup was caught up in the war situation .. ."1IXI Whilst Gowe was not adversely affected since it was perceived as an African scheme, the core estate was because it was seen as representing white enterprise. For Petros Bvunzawabaya, a former Sanyati estate manager, the struggle (Second Chimurenga) caused some production stoppages such as confining peasant workers to protected villages ("keeps")101 and also hindered labour procurement. A curfew, which restricted movement from 3 o'clock in the afternoon to 8 o'clock in the morning, had been imposed on the surrounding community. This meant that many hours of production were lost while the colonial state stepped up efforts to defeat the guerrillas by ensuring that they would not be in contact with the villagers who were accused of harbouring and feeding them. During the war and with the introduction of cotton in 1963, some Gowe tenants were also reluctant to provide labour and concentrated on their own plots despite of the fact that the small-scale scheme was meant to be the estate's labour repository. Several rural development projects were also hampered.

At the end of the war in 1979, many people foresaw massive land redistribution as had been promised by nationalist leaders. All parties campaigning in the 1980 election that brought President Robert Gabriel Mugabe's government into power expected that land use and redistribution was would become particularly important under a majority rule government, especially where some of the more "land hungry" Tribal Trust Lands (TTLs)102 were concerned. In the Gowe Scheme despite the determination of the smallholder irrigators to use the environment created by independence to improve their yields, their efforts were frequently hampered by the perennial cultivation of very small plots including lack of rights and the omnipresent influence of the ARDA Estate. No major effort was made to achieve a meaningful and equitable distribution of land between Gowe and the Main Estate.103 The distribution of income was also skewed in favour of the "big landowner" the Main Estate. The "crisis of expectations" that arose in the early post-colonial period certainly contributed to the 2000 land invasions.

Prior to 2000, very tenuous, fragile relationships existed between the plotholders and the Estate on the one hand and the government on the other. The major bone of contention was the inadequate size of the plots allocated to black farmers and the highly unpopular lease agreements. As shown above, when the people's aspirations after independence were not met, there was a "crisis of expectations". There had been a general belief that more land would be made available and that land rent for the use of the land would be scrapped.104 This disappointment was partly responsible for the unilateral seizure of vacant plots105 by land hungry plotholders.

The demand for land was not only exacerbated by the changing political and economic landscape of Zimbabwe as a whole. It was also complicated by the unilateral claim to other plots by land-hungry plotholders whenever these fell vacant. In the Gowe Irrigation Scheme, some farmers were able to expand their holdings by illegally laying claim to plots vacated by those going back to their dryland homes, or those who had just acquired land in the NPA. In competition with the smallholder farmers, ARDA also laid claim to vacant holdings. For example, in the 1989/90 season, of the total Gowe area of 120 ha under cotton, the outgrowers were cropping only 86 ha, whereas the Estate was using the 34-ha vacant plots.106 During the DC's tenure rules were laid down on how vacant plots would be filled but independence introduced a new form of land grabbing (madiro) at Gowe and on the Estate. Land grabbing became rife, with vacant plots being targeted.

As plotholder families were growing in size, some daring individuals began the unofficial tactic of seizing the land of those who had left the area for various reasons. Because land was never made available to the offspring of plotholders or "the rising stars"107 as one of Mjoli's sons, Weddington, calls them, their parents used their own resources and the inflow of capital from their migrant sons to plough more land which they viewed as lying idle after it had been vacated. This was a way of laying claim to the vacant plots on behalf of their children who were staying with them or were away performing wage labour. Such unilateral seizures of land actually took place despite of the fact that the settlement officer frequently warned the tenants against this illegal practice. The full text of one of his warnings read:

Please be warned that illegal plots are prohibited. Therefore you are only permitted to cultivate those plots allocated to you when the scheme was initially demarcated. The degree of erosion on illegal plots is alarming. Moreover there are no conservation works. The land you are cultivating was earmarked for residential sites. In future, anyone found practicing illegal cultivation will lose his/her plot}108

Indeed, due to the ongoing cultivation of the small patches of land, the soils eventually became exhausted. Even the Chavunduka Commission of 1982 acknowledged that the process of land degradation was increasing at a rapid and frightening pace.109 Overcrowding and the attendant problem of soil erosion could not be solved without allocating adequate land to the Gowe plotholders, the majority of whom were "master farmers" who were accustomed to tilling bigger tracts of land in their home districts. Additional land was required to accommodate these people satisfactorily.

Even the ARDA regional manager for Mashonaland, B.M. Visser, admitted that the size of plots at Gowe were inadequate if the farmers were to meet realistic input costs and certain fixed charges.110 Consequently, a proposal was made that plots should be increased to a minimum of 2,8 and 2,4 hectares, and a maximum of 3 to 4 hectares, for Gowe I and II respectively.111 It was envisaged that this decision would encourage those participating in the scheme to devote all their energies to the venture to realise increased returns and at the same time would solve the problem of dual ownership of land. Nonetheless, the proposed plot sizes were still not adequate to meet the subsistence and cash requirements of the plotholders. A great deal needed to be done by the government to achieve a more equitable distribution of land among the peasantry across the board.

Because many plotholders were rural accumulators who were hungry for additonal land, they availed themselves of the opportunity to cultivate extra pieces of land whenever plots fell vacant. Sometimes they encroached on land that had not been set aside for cropping. The Estate manager even conceded:

For years both the Estate Management and the [Rural Development Planning Unit] RDPU Officers have turned a blind eye to the illegal cultivation (ploughing beyond their land requirement) of the ARDA farm by the registered Gowe settler farmers. This malpractice has only got worse over the years and by now [1988] the whole settler residential area is under cultivation. 112

The practice of illegally ploughing vacant plots assumed major proportions between 1990 and 2000. The process that led some farmers to plough more land than others helped to redefine positions of authority, relationships and social status in the ARDA irrigation schemes. It culminated in the emergence of resource-rich as well as resource-poor plotholders. Both rich and poor irrigators are clinging to such land for the benefit of their absent sons working in town and for speculative purposes. In the period, 1990/911995, which fell within the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme, (ESAP)113 desperate plotholders embarked on seizure of both vacant plots and Estate land in order to make ends meet. There were also many socio-economic problems wrought by this adjustment programme, including the lack of markets, low prices for agricultural commodities and high levels of unemployment. These problems, which invariably persisted into the post-ESAP era, meant that the period 1990 to 2000 was characterised by increasingly desperate measures to acquire land.

ESAP and beyond

In the post-1990 period a number of socio-economic and political changes occurred which impacted on the process of land reform. The problems confronting Sanyati agriculture and the effects of economic liberalisation on the area's irrigation economy were clear. During the ESAP period, hordes of people were made economically redundant when they lost their jobs during massive retrenchments. These people were either released into the rural economy where opportunities to start a new life as a farmer were limited, or they opted to stay in the cities where they led miserable lives.

As far as Sanyati was concerned, the early 1990s experienced a huge influx of "immigrants" most of whom were retrenchees from the giant Zimbabwe Iron and Steel Company (ZISCO); the state-run ARDA Estate; the agricultural marketing parastatals (COTTCO and GMB); and other companies in Sanyati, Gweru, Kwekwe, Kadoma, Harare and Bulawayo. Several skilled and semi-skilled workers were laid off from their jobs when enterprises began to downsize their operations.114 Commercial farms around Sanyati offered retirement packages to a number of farm workers. Many mines also retrenched workers and most of these families found their way into Sanyati villages, but there was nowhere to invest their earnings. Fresh land allocations had ceased in the 1960s as this resource had already become scarce. Despite irrigation's proven benefits to the rural community115 irrigation plots were too limited in number and too small to absorb all the victims of retrenchment and forced retirement. Although according to official statements vacant holdings could indeed be taken up by those who wished to do so, in practice it was not as easy.116

During the difficult 1990s, some Gowe farmers thought they could resuscitate dwindling accumulation prospects by abandoning cotton in favour of other crops such as maize and beans, demanding the transfer of the management of the scheme (devolution of power) to the plotholders and embarking on a process of land grabbing. Thus, this period witnessed the open onslaughts not only on the rising number of vacated plots but also on Estate land.

The economy of Sanyati and that of Zimbabwe continued to be adversely affected by an economic environment characterised by falling commodity prices; rising protectionist barriers; and heavy debt service burdens under ESAP. The devastating droughts of 1992 and 1994 made matters even worse.117 Following the "horrendous drought" of the mid-1990s economic reforms suffered a major setback. According to Mlambo, the programme (ESAP) that opened with a drought also "bade farewell with a second drought in 1994/95".118 Because of drought and other export-oriented difficulties one of the problems during ESAP was mounting "parastatal debts".119 As a consequence, ARDA was unable to extend its usual services to Gowe. It had traditionally provided loans, tillage, marketing and other services to the Gowe outgrowers. For the ARDA CEO, J.Z.Z. Matowanyika, "The Agricultural and Rural Development Authority was pushed into a survival mode by ESAP. Structural adjustment denied ARDA the resources to support the smaller scheme [Gowe]".120 This caused a great deal of indignation and anxiety among the plotholders who wondered how, under the circumstances, their plight was going to be ameliorated. Driven by the sheer need to carve out new accumulation prospects, some Gowe farmers embarked on the invasion of Estate land in 1992.

Invasion of Estate irrigation land (1992-2000)

Demands by the peasantry for larger plots and more fertile land in Zimbabwe date back to the colonial period. In Sanyati such demands were more clearly articulated after the passage of the NLHA when land-hungry farmers resorted to numerous strategies ranging from outright purchase to clandestine seizure of land through the informal madiro system. In Edziwa Village to the South of the Main Estate, madiro became rife. Edziwa Village was established when the remnants of the Rhodesdale evictees were settled there by the colonial government in 1954 under Headman Virima.121 In 1992 people from different surrounding areas such as Lozane, Mudzingwa, Dubugwane and the Gowe Irrigation Scheme invaded the Estate area adjacent to the village, which is now headed by village lleader, Edziwa. With the coming of these people, the village was extended and subsequently divided into the "Old Line" (comprising the 1954 settlers) and the "New Line" which was established by settlers who arrived in 1992.122 The "New Line" now surpasses the older settlement in size. It has 75 households whereas the "Old Line" has 30.123 The inhabitants of the "Old Line" were not affected by the removals in 1974 to pave way for the Sanyati Main Estate.124 They did not fall within the boundary demarcated for that project. However, the people who form the "New Line" are illegal settlers because they invaded Estate land.

Hlalisekani Dube who now occupies a five and a half hectare plot left Lozane Village, Ward 24, for Edziwa in April 1993. He and his father embarked on this move because they argued that they had accumulated a lot of cattle and therefore wanted "a big place" to farm and keep their cattle.125 They were also driven by what they called "very fertile soil for any type of crop, for example, cotton, maize, groundnut and sorghum which do very well [in that area] even without the application of chemical or artificial fertilisers".126

In 1994, Edziwa people from "New Line" were forced by the government to vacate Estate space they were illegally occupying. They refused to be moved and in this year, in typical Rhodesdale style and in blatant disregard for human rights and the gentle persuasion employed earlier, all their homes were set on fire by Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) from Chegutu. They were then forced to leave ARDA property.127 Some did indeed leave but others simply moved their homes to different parts of the ARDA Estate. However, they all returned during the major land invasions in 2000 and to this day (2012), they continue to live on Estate land.128 The official silence surrounding their illegal stay coupled with the length of time they have remained there seems to be giving their tenure some legitimacy. Clearly, the matter has now assumed political dimensions. It is politically sensitive to resuscitate the idea of evicting (in their case re-evicting) these people from Estate land. Intermittent meetings have been held since 1992 involving the local MP, the estate manager, and other stakeholders over this issue. However, all these meetings confirm the difficulties of taking the route of eviction particularly after repeated warnings by successive MPs in the area that "ARDA should not arbitrarily evict people".129 Thus, ARDA is "failing to regularise things [deal with the invasion of their land] because of political connotations".130