Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Historia

versão On-line ISSN 2309-8392

versão impressa ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.57 no.1 Durban Mai. 2012

ARTICLES ARTIKELS

From Makhaza to Rammulotsi: Reflections on South Africa's "toilet election" of 2011

Johann W.N. Tempelhoff*

Research Niche for the Cultural Dynamics of Water (CuDyWat), North-West University (Vaal)

ABSTRACT

In the run-up to South Africa's 2011 local election, the event was labelled the "toilet election" in the media. The message that struck a sensitive chord in the national newspapers was that some local authorities were not compliant in terms of water and sanitation service delivery. Service delivery, in itself, had been a crucial issue in municipal politics since the previous local election of 2006. Four years later, as local politicians prepared for the 2011 countrywide municipal election, the townships of Makhaza in Cape Town and the rural Rammulotsi near the Free State town of Viljoenskroon, were in the news. There was a pubic outcry because of the undignified manner in which local residents had to use the outdoor toilets that were not properly enclosed. From time to time news reports on the open toilets provided moments of comic relief in a tense election campaign that saw the two leading political parties of the country, the African National Congress and the Democratic Alliance, wooing the electorate. The outspoken public disdain over highly unsatisfactory sanitation services, underlined the need for politicians and the management of local authorities to pay serious attention to efficient governance at the municipal level in a democratic society. In the article dedicated attention is also given to the way in which the local election influenced water and sanitation service delivery planning in Moqhaka Local Municipality, the local authority that oversees Rammulotsi township.

Keywords: "toilet election, 2011"; service delivery; water and sanitation sector; local government; local elections; Makhaza (Cape Town); Rammulotsi (Viljoenskroon); civil society, African National Congress; Democratic Alliance.

OPSOMMING

In die tydperk wat die plaaslike verkiesing van 2011 in Suid-Afrika voorafgegaan het, is die benaming van die "toiletverkiesing" aan die gebeurtenis gekoppel. Die boodskap, wat 'n sensitiewe snaar in die nasionale nuusmedia aangeraak het, was die feit dat daar plaaslike owerhede was wat nie in ooreenstemming met aanvaarde praktyke hul verantwoordelikhede ten opsigte van diens lewering nagekom het nie. Dienslewering opsigself was sedert die vorige plaaslike verkiesing van 2006 'n kritieke gesprekspunt. Vier jaar later, terwyl politici hulle vir die volgende verkiesing voorberei het, het Makhaza in Kaapstad en Rammulotsi, naby Viljoenskroon in die Vrystaatprovinsie, in die nuus opslae gemaak. Daar was duidelike openbare ontevredenheid met die onmenswaardige wyse waarop plaaslike inwoners behandel is deurdat hulle spoeltoilette sonder behoorlike afskortings moes gebruik. Nuus omtrent die toilette het van tyd tot tyd vir komiese verligting gesorg in 'n verkiesingstryd wat deur hoë vlakke van openbare spanning gekenmerk is as gevolg van die intense veldtogte van die regerende African National Congress (ANC) and die Demokratiese Alliansie (DA). In die artikel word in die besonder ook aandag gegee aan die wyse waarop die verkiesing beplanning rondom water en sanitasiedienslewering geraak het in Moqhaka Plaaslike Munisipaliteit, waarin Rammulotsi geleë is.

Sleutelwoorde: "toiletverkiesing 2011"; dienslewering; water- en sanitasiesektor; plaaslike owerhede; plaaslikeverkiesings; Makhaza (Kaapstad); Rammulotsi (Viljoenskroon); burgerlikesamelewing; African National Congress (ANC); Demokratiese Alliansie (DA).

Introduction

There are indications that South Africa's countrywide local election of May 2011 has been entrenched in contemporary historical consciousness as the "toilet election".1 For the country's political leadership the fierce tussle to win the hearts and minds of the 22 million eligible voters, the issue of sanitation would ordinarily have been too mundane. Sanitation politics, for one, are not as flashy as the customary clash of the titans in the national political arena, where issues of power are customarily used to make the public aware of the authority political parties wield in the country's chambers of political deliberation. However, what began in 2010 as the proverbial storm in a teacup over unenclosed toilets in the Cape Town suburb of Makhaza became - within the space of less than a year - a veritable downpour of negative publicity countrywide that provided voters in many parts of South Africa with food for thought before casting their vote in the local election of 18 May 2011.

In their reflections on the event, communications experts studying the latest global information technology trends noted that in the case of South Africa's local election the issue of unenclosed toilets stole most of the thunder.2 In stark contrast was the fact that in other parts of the world, where social media such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube were abuzz with talk of the "Arab Spring" of 2011 in North Africa and the Middle East, civil society used mobile technology to demand the democratic right to elect the government of their choice. 3 The ability of social communications networks to become a cyber heterotopia4 and articulate what the people demanded, made a strong statement on the potential of communications technology at the disposal of civil society.5 In the case of South Africa, the powerful message of sanitation issues prevented the event from being labelled the "social media election". Images of violent protest, unenclosed toilets and reports of inadequate sanitary service delivery became synonymous, for political analysts, with local government failure, the need for more effective and disciplined leadership and the call for comprehensive and democratic participation in institutional development.6

At centre stage of the media focus were some 2 000 water-based, but unenclosed, toilets in the Makhaza suburb of Cape Town's Khayelitsha township and Viljoenskroon's Rammulotsi township in the rural Free State Province. Although there were rumours of similar open-air toilet facilities in other parts of South Africa, Makhaza and Rammulotsi stood out as role models. The one local authority was under the control of the Democratic Alliance (DA) in the Western Cape; in the other, the African National Congress (ANC) was at the helm. The contrast did not end there. In socio-economic terms Makhaza had the profile of a typical metropolitan urban environment - an informal settlement in a complex transitional phase of becoming an integral part of the rapidly growing city of Cape Town. Rammulotsi, on the other hand, was located in an infinitely more placid, rural environment, where locals still had the time to indulge in neighbourly co-existence, civility, and a degree of local pride, despite the hardships associated with poverty in the rural parts of the country.

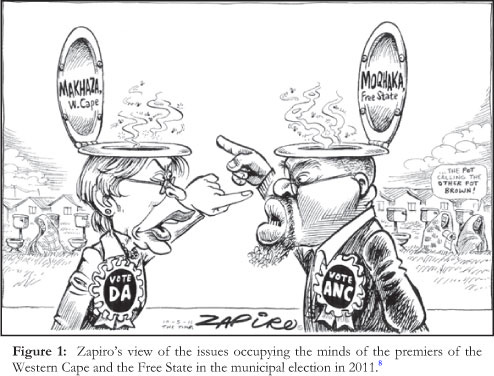

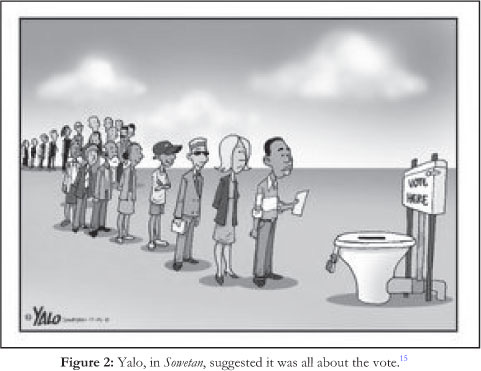

In the media, the hype of the "toilet election" provided momentary comic relief in a hard-fought political campaign. This humour was captured in the wickedly accurate cartoons that showed what was actually going on in the political minds of South Africans. Probably the most basic, but essential, component of municipal local service delivery - sanitation - became a matter for contemplation in the public sphere. It made people aware of the daily social rituals they resorted to in the privacy of their homes. The only difference was that in the case of the toilets under public scrutiny in Makhaza and Rammulotsi, these rituals had to be performed in the public eye because the local authorities' management of sanitation went awry.

The toilets conveyed a sombre message - the callous disregard, in some quarters of South African society, for the plight of less privileged people on the fringes of the country's urban conurbations. An everyday necessity like a toilet - associated with a sanitary domestic lifestyle - became a conduit in the public eye for comprehending just how important it was to respect an individual's privacy. Since the local election, the government's planners have attempted to address the issue. In fact, sanitation has become part of a new strategy aimed at making the country a better place for its people.7 As will be pointed out in the discussion to follow, the toilet election of 2011 contributed significantly to creating public awareness of the circumstances of the less fortunate.

Background and outline

This article forms part of a transdisciplinary research project undertaken by the Research Niche for the Cultural Dynamics of Water (CuDyWat) at North-West University's Vaal Campus in Vanderbijlpark. The project's focus is on environmental health and service delivery in the water supply and sanitation sector of Fezile Dabi District Municipality in the Free State Province. At the beginning of 2011, the municipality commissioned CuDyWat to conduct this research as part of a strategy to improve water supply and sanitation service delivery in two of its local municipalities, Moqhaka and Mafube. In the one section of the report, the research team provided feedback on their on-site appraisals of Moqhaka's local water supply and sanitation infrastructure. Another section dealt with an assessment of the perceptions of municipal service users and water workers. Other themes included: how the regional hydrogeology shapes the local environment; indications of climate change; and the implications of population movements (migrations). All these factors have a marked influence on the governance and management of the municipality's urban nodes (Kroonstad, Viljoenskroon and Steynsrus) as well as on the local water supply and sanitation infrastructure.9

In the discussion to follow, attention is given to some of the political dynamics that come into play when municipal water supply and sanitation is contemplated from the perspective of a history of the present.10 Political parties participating in South Africa's local election of 2011 were loudly articulate on sanitation issues and the need for more effective municipal service delivery. They voiced the frustrations of residents in the country's rapidly developing urban areas. In the first part of the discussion below, there is an exposition of the origins, in Khayelitsha, of the sanitation discourse prior to the election campaign. We then see how Rammulotsi, in the rural Northern Free State, became part of the discourse, before turning to the aftermath of what can be labelled the "toilet election". Attention is then given to municipal service delivery in South Africa since 1994, culminating in a discussion on water and sanitation services. Finally, aspects of CuDyWat's Moqhaka report are discussed, pointing to the manner in which history and a sense of memory (historical consciousness) inform our understanding of contemporary service delivery problems.

The origins and development of the toilet saga: Cape Town

It all began on 21 January 2010, when a local branch of the African National Congress Youth League in Cape Town's Khayalitsha township lodged a complaint with the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) against the city council for providing toilets without proper enclosures in Ward 95 (Makhaza).11 It was, they argued, an infringement of the rights, dignity, privacy and freedom of residents to endure the unacceptable conditions of having to use open toilets.12 Cape Town city councillor, Stuart Pringle, responded by explaining to the media that in 2007 there had been an agreement with the community that unenclosed toilets would be erected. The intention of the council was to do away with undesirable and unhygienic communal toilets. The municipality, in consultation with all stakeholders, then made use of a contractor to erect 1 316 freestanding toilets; no provision was made for a modicum of privacy. The understanding was that the owners of the new government sponsored houses would have the use of a water-based toilet erected on their residential plots. The responsibility to enclose the toilets resorted to the individual/s concerned and was to be at their own expense. Towards the end of 2009, of the 1 316 toilets, 1 265 had been enclosed. Only 51 remained standing in the open.13 By January 2010, the agreement made three years earlier had all but been forgotten as political tempers flared. Accusing fingers were pointed at the Democratic Alliance (DA) controlled City of Cape Town's municipal management. The Pan Africanist Congress's Clarence Mayekiso argued:

We don't accept that the city has no funds to build proper toilets for our people, as we know that Cape Town has got the best suburbs in the country, comparable to the best in the world.14

In an effort to address residents' discontent, the municipality's officials arrived in the township on 25 January to enclose the toilets with corrugated roofing material. They were prevented from doing so by residents who were presumably supporting the cause of the ANCYL.16 Subsequently, makeshift structures were erected around the toilets on two occasions; these were torn down.17 The matter culminated in a court case with Judge Nathan Erasmus instructing the Cape Town municipality to re-install and enclose all the toilets. Local residents persisted in obstructive strategies to prevent officials from doing so.18 Then, on 25 May 2010, once again after the destruction of corrugated structures, Cape Town's mayor, Dan Plato, decried the vandalism and said that the city had reached the "crossroads"; the confrontation and sabotage could no longer be tolerated.19 Western Cape premier, Helen Zille, herself a former Cape Town mayor, described the actions, which had apparently been initiated by the ANCYL, as "part of a campaign of violence and intimidation" against the DA. She said that she intended taking the matter up with President Jacob Zuma.20 Six days later, on 31 May, 200 people in Khayalitsha came out in protest, burning tyres and complaining about the "removal" of 65 toilets in the Makhaza settlement. In response Mayor Plato, explained to the media:

Given that the city has been prevented from building the remaining enclosures, we have resolved to temporarily remove the toilets until appropriate enclosures have been built ... We are willing to go back and reinstall the toilets as soon as the community reaches an agreement with the Youth League.21

The following day, police arrested 32 people. 23 At the time there were voices amongst the ANC's local leadership to the effect that although there was understanding for the residents' complaints that using open toilets was undignified, it was unacceptable for the toilet structures to be destroyed.24 There were indications that not everyone was in agreement on the way the problem was being addressed. On other matters there was consensus. For example, when on 11 June 2010, the Human Rights Commission's deputy chairperson, Ms Pregs Govender, announced the findings of a report compiled by the commission, she pointed out that the open toilets had violated the human dignity of local residents.25 The commission recommended that the council re-install the toilets and enclose them with bricks and mortar.26 One of the reasons for the recommendation was that the commission was aware that the corrugated material used for enclosing the toilets was not bullet proof and people were vulnerable to attack while they were using the toilets.27 This reasoning was not without substance; there had recently been several reports of incidents of this nature in Cape Town townships.28

The toilet situation had meanwhile attracted the attention of leading figures in Cape Town. The city's Anglican Archbishop, Thabo Makgoba, let it be known from London, where he was on an official visit, that he would be prepared to chair a meeting between the political leadership of the local authority and the discontented residents. His offer was based on the fact that he was concerned about a "potentially explosive situation at Makhaza, which seems to suggest that God's people are desperate for ... compassionate and decisive leadership before their grievance turn[s] into more turmoil for larger society".29

Towards the end of June 2010, a closed meeting took place at the Solomon Mahlangu Community Hall in Khayalitsha; Zille and Plato negotiated with members of the ANCYL. Co-operative governance minister, Sicelo Sicheka facilitated the meeting. Fifteen minutes after proceedings began, Zille and Plato walked out because the Youth League had apparently threatened to make Cape Town "ungovernable". 30 Later, in her weekly newsletter, Zille explained that there were too many inconsistencies and contradictions in the toilet saga. She argued that the toilet construction project leader, Andile Lile, said to have been behind the ANCYL's actions, had only started protesting about the unenclosed toilets, at the end of 2009, by which time the project had been 96 per cent completed.31

The fact of the matter was that the political spin by the ANCYL on the open toilet saga was planned to last until the day the voters went to the polls in the country's local election. Ultimately the objective was for the ANC to regain control of Cape Town. Understandably politicians did not hesitate to land a blow or two if and when the opportunity presented itself. In July 2010, Sicheka, boasted that the shameful goings on in Khayalitsha could only happen in Cape Town.32 He insinuated that this was the type of local governance that could be expected in the DA-controlled Western Cape - not in the rest of the country. This remark soon proved to be political posturing. Shortly afterwards a report appeared in a Sunday newspaper, to the effect that a large number of unenclosed toilets had also been installed in the Free State town of Viljoenskroon. Conditions there appeared to be even more detrimental to human wellbeing than in the case of Cape Town. The 74-year-old Ms Paulina Tonyane told a City Press reporter that she had reverted to using the pit latrine on her property because children were always using her unenclosed toilet. She felt that it was unsafe and furthermore, was acutely embarrassed to use the facility out in the open.33

Meanwhile, in an effort to get to the root cause of the furore about Makhaza's toilets, Cape Town City Council issued a report setting out the facts of the matter. It was explained that residents had been given the opportunity to either continue using the old system or to opt for the "loo with a view".34 The Social Justice Coalition (SJC), a nongovernmental organisation (NGO) in the Western Cape, that had scrutinised the report, announced that the affected community had not been consulted adequately in the process of planning and executing the construction project.35 Furthermore, it did not appear to be impressed by the use of the catchphrase "loo with a view". The toilet saga continued to smoulder for a considerable time in many sectors of Western Cape society. It surfaced from time to time, even in unrelated protest actions.36

When in March 2011 the court case against the Cape Town Council resumed in the city's High Court, the legal representative for the Western Cape's human settlements MEC explained that although the installation of unenclosed toilets in Khayelitsha was controversial, it was by no means unconstitutional.37 Lawyers representing three residents of Makhaza insisted that the court accept the recommendations of the Human Rights Commission that the toilets be enclosed with concrete structures.38 By the time judgement was handed down in the Western Cape High Court in April 2011, the toilet saga was a fully blown national affair with a number of political dignitaries offering their unsolicited opinions on the public spectacle. For example, on the day of the judgement, ANC Youth League president, Julius Malema, arrived with aplomb at the court; there was loud music playing from speakers in the proximity of the court building. He was greeted by a crowd of onlookers triumphantly waving ANC banners.39 The court case was a victory for the ANC. In his judgement Judge Erasmus said that the City of Cape Town had violated the dignity of residents and gave the instruction that the toilets in Makhaza be enclosed with bricks and mortar.40 Helen Zille immediately indicated, on behalf of the DA in the Western Cape, that the judgement would be honoured. For its part the City of Cape Town explained that it was in the process of studying the judgement.41 The South African Communist Party (SACP) welcomed the ruling, noting that the DA had been exposed for its lack of moral authority in the process of the governance and delivery to the people.42

The toilets of Rammulotsi

While the drama of Cape Town's toilet saga was playing itself out, another toilet issue came to the fore. The toilets in the Rammulotsi township of Viljoenskroon, part of the Moqhaka Local Municipality were standing in full view; they had not yet been enclosed despite the fact that they had featured in the local and regional news for several months. On 8 May 2011, a spokesperson for the Human Rights Commission told the media there were more than 1 600 unenclosed toilets in Rammulotsi. They had not been enclosed in the more than eight years since their installation. The DA leadership was angry. The Human Rights Commission had been asked almost a year earlier to bring out a report; apparently nothing had been made public.43 After the commission, almost as an aside, let it be known that it would bring out a report on the issue, there was a public outcry. Moqhaka's manager of technical services, Mr Mike Lelake, tried to stem the tide of public criticism by explaining that the cash-strapped municipality needed money to enclose the toilets.44 Such excuses did not convince the public of the municipality's innocence. On 10 May 2011 a high profile ANC delegation comprising ANCYL president, Mr Julius Malema, Mr Fikile Mbalula, the minister of sport, and Mr Tony Yengeni, a member of the ANC's National Executive Committee (NEC), visited Viljoenskroon to inspect the toilets at Rammulotsi for themselves. Moqhaka's mayor, Ms Mantebu Mokgosi, explained that the project had been initiated with a view to finishing it in different phases. The first was to dig the canals for the pipes and lay on the water, after the installation of the toilets. The second phase was to enclose the toilets. Malema did not accept the explanation and said heads had to roll.45 The situation was exacerbated when the media discovered that the mayor herself was the councillor for the ward in which the toilets stood. Worse still, her husband had been the contractor responsible for installing the toilets without quite completing the project.46 The ANC's response to the issue in Viljoenskroon was, in the words of the party's Brian Sokutu, a matter of principle: "We have preferred not to run away [from the issue] because it's a municipality run by the ANC and we therefore take full responsibility".47

For the politicians of the ANC-controlled Local Municipality of Moqhaka, matters took a turn for the worse on 13 May 2011, when the mayor was literally obliged to run away from a protest in which an estimated 3 000 local residents of all races marched to the municipal offices in Kroonstad. Behind the march was an organisation called Gatvol Kroonstad, acting as an NGO of sorts. It was formed in early 2011 by a group of concerned local business people who refused to tolerate the alarming rate at which public amenities had deteriorated in Kroonstad. 48 There were potholes in the city's streets, frequent electricity outages, leaking sewers and sub-standard municipal drinking water. Gatvol Kroonstad blamed the local ANC councillors for the deplorable state of affairs. The opposition Congress of the People (Cope) and the DA exploited the situation to the full. They had apparently "infiltrated" Gatvol Kroonstad and supported the NGO's activism - for their own ends. 49 It was seemingly a matter of the political parties opportunistically seizing upon any available vehicle prior to the impending election - in a last ditch effort to win the support of the voters.

On the day of the protest the residents officially lodged a complaint about inferior municipal service delivery in a number of areas. The crowd even carried symbolic coffins labelled "RIP" to denote the "funeral of Moqhaka". When the mayor turned her back on the crowd, angry words were shouted at her over a microphone. The mayor responded by telling the media: "The people do not pay their taxes ... More than 50% are unemployed." 50 The media exploited the situation to the full. In interviews, women told a reporter how aggrieved and embarrassed they felt to use the unenclosed toilets. One said she wrapped herself in a blanket at night while using the toilet. Another said that she did not want to carry on living in such destitution and that God should rather take her away.51 There were also reports, not all of them true, to the effect that in other parts of the Free State similar conditions prevailed. The towns of Wesselsbron, Theunissen, Winburg and Brandfort were mentioned. In some places, it was alleged, the toilets were not even connected to the water mains.52

On 16 May 2011, two days before polling day, the Human Rights Commission's deputy-chairperson, Pregs Govender, read out a statement on behalf of the commission - this time against the Moqhaka Local Municipality for violating the residents' human rights by not providing adequate toilet facilities in the town of Viljoenskroon.53 In the media it was reported that the mayor of Moqhaka had become a "liability" for the ANC in the Free State.54 The besieged minister for cooperative governance, Sichelo Sicheka, meanwhile tried to dodge media and ANC criticism of his part in the toilet saga by explaining that it was the responsibility of his cabinet colleague, Tokyo Sexwale, the minister of housing. The blame, he argued, could not be placed on the shoulders of President Zuma who had only come to office once the open toilet debacle was already under way as part of housing development in the townships.55 Sexwale, shortly before, had told a public gathering in Mitchell's Plain that his department had taken over the construction and provision of toilets from the department of water affairs. The explanation was: "We want to make sure that sanitation is not used as a political football. We want to make sure that service is delivered." Sexwale brought in ANC stalwart, Ms Winnie Madikizela Mandela to act as one of the ambassadors for the new government initiative. The toilet saga had finally achieved the status of the preeminent feature of the 2011 local election. As a plaintive newspaper editorial put it, "Who would have thought that political points could be scored - or lost - as a result of toilets?"56

The aftermath of the toilet election

The toilet election of 2011 can be evaluated from a number of perspectives depending on the observer's vantage point. For example, from a management perspective it is fair to say that it was a wicked problem that arose when the workers and planners lost touch with the real life experiences of people who make use of unenclosed toilets. In the aftermath of the election, the obvious solution was for the responsible politicians and officials to set things right by enclosing the toilets. Different discourses emanating from post-election developments in Makhaza and Rammulotsi tell the story of the stark contrast between conditions in South Africa's metropolitan and rural urban areas and their water and sanitation infrastructure.

In the case of Cape Town's Makhaza the city council, in conjunction with a number of civic-minded groups and individuals, promoted initiatives to create awareness of sanitary matters. By September 2011, Cape Town mayor, Ms Patricia de Lille, announced a special R138 million Job Creation Programme to see to it that the 28 per cent of the city's population who did not have proper access to sanitation, were provided for.57 In the same month, the Social Justice Coalition hosted the first Cape Town sanitation summit. This opened the way for local representatives, activists, government representatives, technicians, academics, experts and other stakeholders to discuss joint plans to improve access to clean, safe and appropriate sanitation facilities in Cape Town's informal settlements.58

In the case of Viljoenskroon's Rammulotsi, there were some obstacles to making meaningful headway. In August 2011, the 150 enclosures that had already been built around the open-air toilets had to be demolished because too little cement had been used in the construction process.59 By November 2011, the work was still incomplete. But the "good news" was that the Development Bank of Southern Africa had granted a loan of R7 million, which along with R2 million provided by the provincial department of human settlements, potentially covered the costs for the work to be done. It also meanwhile became apparent that apart from Rammulotsi's toilets, there were in total some 2 800 units in other Moqhaka urban settlements, such as Kroonstad and Steynsrus, that were in dire need of repair.60

The local election and specifically the toilet saga, highlighted the sensitive issue of sanitation in South Africa. What was certain was the fact that local authorities would in future have to deliver on the residents' demands for proper sanitation. The central government was also made acutely aware of unsatisfactory governance in the country's municipal sector. A week before the local election a confidential document, intended only for the eyes of the cabinet, was leaked to the media. It contained the worrisome information that at the end of the 2009/10 book year, 46 of the 283 municipalities had not submitted their financial documents. Moreover, an estimated 70 per cent of the reports on service delivery submitted by local authorities were so unreliable. The lack of efficient leadership at the local level made it necessary for provincial and national government to oversee matters in municipalities. 61 Analysts pointed to warning signs. R.D. Russon explained that local elections would in future become increasingly important. The country's political parties would have to start taking a different view of local politics. Whereas in former times local politics were often neglected, indications were that the neglect of local political interests would come back to bite them in the foreseeable future.62 For Mcebisi Ndletyana, there were indications that the ANC was alienating some of its traditional supporters because of insubordinate leadership within the party.63 For the DA, the message was that although they had made a significant breakthrough, there were no grounds for over confidence; there was little hope of taking over the government for decades to come. The chances were slim that black voters who had fought so hard for their political liberation would be prepared to relinquish their support of a black-based political party.64

Some public relations specialists saw the toilet saga as a "resounding victory" for the ANC. Thabane Khumalo of Think Tank Marketing Services argued that the DA went on the defensive in Cape Town while the ANC, in contrast, had resorted to interacting with the dissatisfied residents of Viljoenskroon.65 They had sent Julius Malema, Fikile Mbalule and Tony Yengeni to speak to the people.66 Even before the election, the ANC in the Free State made a concerted effort to open up the can of worms and take the public into their confidence. For example, the ANC told the media that the issue of Moqhaka's mayor, whose husband had not completed the toilet construction project satisfactorily, would be "put right". 67 But by no means all the experts were in agreement on this "winning" theme. Pundits in City Press pointed out that although the toilet issue had provided negative publicity, especially with Malema emerging as a "plumber" in the toilet saga, it was unlikely that the ANC would lose substantial support. 68 A Western Cape commentator, on the other hand, considered that the ANC had emerged from the debacle as almost nondescript, while the DA figured "very well" and had maintained a "high profile" throughout the debacle.69

Journalists reporting on the blow-by-blow news of the toilet saga were more cynical. The Volksblad saw it as a typical tiff between political parties on the eve of an important election. The DA, it explained, deserved to be rapped over the knuckles for showing scant concern for the dignity of people on the Cape Flats. However, at the same time, the newspaper criticised the ANC for its confident display of financial wellbeing while the leadership was apparently blissfully unaware of what was happening at grassroots level70In an editorial, the South African Journal of Science suggested philosophically that:

In mature democracies most governments are assessed by their electorates on the basis of "delivery" issues. But in South Africa in the past, issues of race and loyalty have prevailed. The presentation of viable alternatives - whatever form they may take - at local government level across the country, should convince the electorate that democracy is about making choices related to performance.71

It was evident to media practitioners that the toilet debacle was symbolic of voters' discontent with service delivery.72 Although the toilet issue, as is the case with most preelection sparring, was at times discussed in a superficial manner, 73 there were some concerted attempts to take a closer look at the underlying issues. For example, Stellenbosch University sociologist Steven Robins explained that prior to the electioneering phase, open toilets had not been an issue; the focus had been on poor service delivery in general. People had seldom linked service delivery grievances with sanitation and toilets. Instead they complained about corruption, poor housing, water and electricity.74 He suggested that the issue of the open toilets became "viral" when it was perceived as an onslaught on the dignity of black South Africans. Dignity and privacy appeared to be uppermost in the minds of the people. It was also related to the historical memory of not being respected in the apartheid era, as Judge Erasmus had explained when delivering his judgement on the Rammulotsi case.75

In the confines of the Social Justice Coalition there were some valuable insights on sanitation that had not been discussed in the public realm before. The NGO explained in a statement that:

The provision of sanitation is one the most important functions of local governments. It is good that the ability to use a clean and safe toilet - traditionally a very private act rarely discussed - has become a focal point in the run-up to the municipal elections, but it is a pity that it is not being done in a positive manner with critical reflection on one's own performance. Political parties have instead passed the blame, and sought refuge in the relative under-performance of other areas. Every municipality has a duty to ensure that the right to basic sanitation for every resident is progressively realised.76

There were also observations from other commentators who spoke of the powerful effect of graphic images of women sitting on open toilets. It seemed to Judith February of the Institute for Democracy in South Africa (IDASA) that politicians were simply not listening to what the people were saying.77 Moreover, although the evolving terminologies, such as "loo with a view" and "cabriolet toilets"78 were humorous, they also seemed to imply a description that was offensive. It was all about the non-political, private milieu being elevated to a political ploy in the public sphere.79

Given the fact that the government's National Planning Commission had earlier made the "human condition", the centrepiece of an impressive planning document on the way ahead for development in South Africa, it seems appropriate to think in terms of the reasoning of the late Hannah Arendt. When one examines her view on life and the theory of politics it is clear that simple dignity and respect for personal privacy was undermined in this case by political discussion that was not directed specifically at trying to solve a given problem. Instead, they merely acknowledged certain imbalances in the socio-ecological sphere that had been aggravated by the politics of the moment; the reactions were devised to win support in the market place of communication for identifiable political organisations in leadership roles. In many respects it was the misrecognition of a Mitwelt experience in an underprivileged society, over an issue of water and sanitation transfer, which created an environment of short-term political enmity in two contrasting South African urban environments. The fact that the furore was about material infrastructure, something that everybody accepts as being available in an ordinary urban domestic environment, suggests that it is in essence a non-issue. It reflects only on the decline of built structures, the necessity of water and the basic human need for relief - something in itself as important as breathing oxygen or taking in essential supplies of water to sustain the human condition.

If anything can be deduced from the trends that analysts have identified in the aftermath of the 2011 local election, it is that local elections will gain increasingly in importance as the residents of urban areas across South Africa start putting issues of race on the back burner. Instead they should insist that the people who represent them in the political chambers of the country must be more aware of basic local facilities and the need for proper services. Proper service delivery, it seems, is not negotiable. In the next section some dimensions of the issue need to be highlighted to gain a better understanding of the significance of the "toilet election" in Moqhaka Local Municipality's Rammulotsi township.

Service delivery in South Africa

Since 1994, municipal service delivery has been one of the crucibles of development and governance in South Africa. A complex set of socio-economic and political factors have contributed to making effective local government the exception to the rule, especially in the rural areas. Some of the persistent problems experienced - specifically in respect of municipal water and wastewater treatment service delivery - have been:

• Insufficient capital investment in the construction and maintenance of water purification and wastewater treatment works infrastructure.

• Shortages of suitably qualified human resources with the necessary skills to operate sophisticated plants.80

• The inherent poverty of a significant proportion of residents and their inability to pay for costly, but vital services.81

• Making the transition to a new and more all-inclusive system of participatory local government without undermining local management capacity and a sense of local patriotism in rapidly growing local authorities, spread out over large areas in the rural parts of the country, and in high density metropolitan areas.82

The issue of service delivery in political discourses on South Africa's local elections of 1996, 2000, 2006 and 2011 has an interesting, but convoluted history. A salient trend has been the tendency for the electorate to speak with one voice. For example, in the 1990s, previously disadvantaged urban residents were much less inclined to complain about services than their more affluent (predominantly white) neighbours.83 By 2011 there was a distinct voice from the electorate berating inferior municipal service delivery.84

In 1994, the time of the transition to a new multiracial democracy, most South Africans in urban areas were loath to accept higher rates and property taxes. Whites were aggrieved; they felt that their contributions had to pay for services extended to previously disadvantaged South Africans. South Africans of colour assumed that the government would be considerate of their economic situation. Local authorities, in turn, were eager to get things done. Consequently, they promoted the principle of the payment for services. This marked a distinct shift in municipal management planning since the old dispensation. For example in the 1980s, mass rent and rates boycotts were the order of the day in townships across the country. By 1994, the national government's masakhane campaign focused on persuading people to pay rates and taxes for service delivery. The project achieved limited success.85 On the whole, services rendered by local authorities appeared to be a matter of social solidarity and support for people from previously disadvantaged backgrounds. The need for the payment for service delivery did not form a significant part of the discourse on the first local election of 1996. The sheer individual act of an adult citizen of the country participating in an election was, for all practical purposes, an existential experience to cherish. Particularly for newly enfranchised South Africans, the opportunity to vote was a novelty. All and sundry wanted to affirm their support for the political party of their choice. The real issues of local government were unimportant. What was needed was an alignment, a synergy of the South African electorate with the local, provincial and national structures of representative democratic governance.

By 2000, there was a change in the public discourse prior to the local election. There were indications of territorial diversification in the way political parties communicated their message to win the support of the electorate. The terms "delivery" and "services" were used frequently and more often than not in the context of specific local issues. There were even remarks promising "free water services" to eliminate poverty.86 The ruling ANC used the slogan "Let's speed up delivery".87 In one of the provinces a senior politician even warned voters that if they voted for the opposition, they would be the last residents to get service delivery.88 On the whole, the government focused on issues of poverty and the newly formulated UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) aimed at addressing issues of global poverty. Thus 2000/1 saw the introduction of the policy of every South African household qualifying for 6Kl of free water.89 Although poverty was an important factor, there were also concerns about the environmental health of rural water consumption practices. Health experts argued strongly in favour of efficient potable water service delivery.90 Combating contagious diseases, such as cholera and diarrhoea, meant that adequate sanitation services had to be in place.

By the time the local election of 2006 came around, service delivery had acquired a significantly new content. Politicians tended to speak of "delivery" in more subdued tones.91 Experts warned that the neo-liberal policies pursued by the government, those of promoting democratic processes while at the same time adopting a capitalist, free-market system in a developing country, was counterproductive for the interests and welfare of the poor.92 After 2004, South Africa was rocked by widespread service delivery protests that continued to escalate countrywide.93 The international media began drawing comparisons between local service delivery protests and those of the 1980s when South Africa's townships became ungovernable while civil society became embroiled in the last throes of struggle against the apartheid government.94 After the 2009 national election, there seemed to be a decline in the number of local protests. However, the violent nature of these protests has again begun to intensify.95 In April 2011, community protests reached a tragic climax, when the 33-year-old Andries Tatane, an activist who was leading a group of discontented local residents, died in the arms of a comrade after police fired rubber bullets in an effort to control local service delivery unrest in the Eastern Free State town of Ficksburg.96 Tatane's death, filmed by a television news team, left the country momentarily stunned at a time when 22 million eligible South African voters were asked to cast a vote in the coming municipal election.

Service delivery in the water and sanitation sector

Adequate service delivery has consistently been a critical issue for the water supply and sanitation sector of local authorities since the Water Services Act of 1997 and National Water Act of 1998 were introduced. The responsibility of acting as a reliable service provider has proved to be a monumental challenge for many local authorities countrywide that are more often than not under-funded and under-staffed in important technical human resources fields.97 Problems include: faulty water accounts; frequent breakdowns in the water supply; inferior quality of local drinking water in terms of smell, appearance and taste; unresponsive local officials in reaction to residents' complaints about water; dysfunctional toilets; irregular and messy bucket and manhole cleaning; water-based toilets not working; clogged sewage pipelines; non-operational wastewater treatment works; and sub-standard potable water purification plants.98

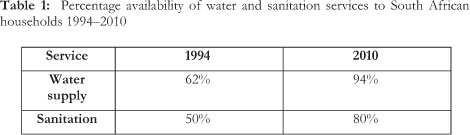

According to an annual survey of South African households conducted by Statistics South Africa since 2002, there have been significant improvements in water supply and sanitation services. For example, in 2010 an estimated 95 per cent of South African households had access to water. In the case of sanitation 80 per cent of households had access to services.99 See Table 1 below.

Although there is little reason for complacency until all people in the country have access to clean drinking water and adequate sanitation as stipulated in the Bill of Rights of the South African Constitution,100 there is reason to believe that the country had made considerable headway in a decade and a half to provide the basic needs of a substantial portion of the country's population. However, service delivery, on the whole, is spread unevenly across the country, with the rural areas potentially falling victim as a result of under-statement in the news media.101 In the next section attention is given to how this situation is reflected in the case of Moqhaka Local Municipality.

Conclusion: the aftermath of Moqhaka's "toilet election"

At the time of conducting fieldwork in Moqhaka in October 2011, the local election of 2011 was something of the past. It was evident that a degree of post-election exhaustion had set in. Although Gatvol's activists continued to monitor the performance of the municipality, they tended to maintain a relatively low profile. Internally they concentrated on generating social networking strategies on Facebook102 and Mobilitate - the latter being an information network aimed at setting up a countrywide database on problems and potential solutions to municipal service delivery issues.103 They also joined forces with other NGOs, such as the Vaal Environmental Justice Association (VEJA) and Save the Vaal Environment (SAVE), operating in the upper Vaal River catchment area. The NGOs collaboratively formed part of a project104 under the auspices of Mvula Trust, a national NGO focusing in on water supply and sanitation issues in the country's rural regions.105 The objective of the initiative is to create greater public awareness and active participation in water and sanitation management matters, and ultimately to promote the formation of citizens' groups to scrutinise water issues.

The residents of Moqhaka's urban settlements shared valuable views with members of the CuDyWat research team on how they perceived local water and sanitation service delivery. With the local election behind them, they seemed to expect something to happen in terms of service delivery. At the same time they were aware that progress would not be apparent overnight. It was as if life was going on as usual. In the Moqhaka research report one section deals with a historical overview of how the problems of local water and sanitation service delivery arose. Working from the perspective of a history of mentalities, researchers framed the perceptions of stakeholders. For example, it is argued that service users experienced a mentalité de déconnexion (mentality of disconnectedness). They felt disconnected from orderly systems that impacted on their daily lives. This had a marked effect on their personal comfort, dignity as well as the ability to plan and lead a reasonably contented life. They tended to experience their social ecological environment in negative contexts. Metaphorically, this mentality is articulated in T.S. Elliot's poem, The Waste Land..106

Municipal officials and representatives of the governing party in the council were also eager to share their views on the problems in the water sector.107 With the election a thing of the past they were more than willing to be transparent and accessible to the researchers as well as the public. However, water sector workers, according to the research team, had developed a mentalité de l'idéalisme ironique (mentality of ironic idealism) that manifested under the adverse conditions of having to keep a vital service delivery sector operational despite a lack of enough funding to maintain and further develop the infrastructure. This mentality appeared to be similar to that of an American marine biologist, Dr Ed Rickett, as outlined by the novelist John Steinbeck in Cannery Row108 and Sweet Thursday.109 In follow-up research, the intention is to try and create local and indigenous discourses reflecting the prevalent mentality of stakeholders110 by means of participatory research strategies.

The report also accentuates the need for the more effective implementation of existing legislation to ensure that environmental health in Moqhaka is not compromised in the hydrosphere111 The council of Fezile Dabi District Municipality and environmental health practitioners in neighbouring administrative areas have given their support for a project aimed at creating transboundary water quality monitoring strategies across district and provincial borders in the Upper Vaal River Catchment.112 In management terms the intention is to make use of the legislation and policy guidelines dealing with intergovernmental relations to promote cohesion in municipal service delivery.113 In terms of transdisciplinary research methodology the objective is to apply strategies conducive to the integration of knowledge and action in a complex governance sectors.114

The role of history as a disciplinary participant in the Moqhaka research project is to nurture and recover memory and to reflect on the manner in which the past informs present and future planning. For example, although the toilet election of 2011 is over and done with, its memory still lingers in the public sphere of Moqhaka Local Municipality where an investment in the cultural capital of water and sanitation infrastructure technology should inform planning and decisions of the municipal management and the political leadership. By sharing ideas on the history of mentalities, migration history, and the history of climate change in the era of the Anthropocene with a broad spectrum of local residents, there should typically be a greater awareness of the value of historical thinking. Moreover, historical consciousness, translated, for popular consumption, as memory, proves its usefulness in research work aimed at addressing some pressing problems currently experienced in South Africa. Finally, in the case of the Moqhaka research project, it is hardly possible to contemplate the dynamics of water and sanitation politics - as reflected in the 'toilet election' of 2011 - without a sound historical perspective.

* Head of the Research Niche for the Cultural Dynamics of Water (CuDyWat), North-West University (Vaal). This article is based on a paper presented at a Water Research Colloquium by the Unit for Environmental Research and Management, North-West University (Potchefstroom), Potchefstroom, 24 November 2011.

1. Reuters, "Toilet Row Grabs Headlines in South Africa", Reuters US Edition, 18 May 2011, at http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/05/18/us-safrica-election-idUSSTRE74H5WU20110518 (accessed 30 October 2011); M. Rossouw and N. Dawes, "The Toilet Election", Mail & Guardian, 13 May 2011, at http://mg.co.za/article/2011-05-13-voting-gets-down-to-basics (accessed 30 October 2011).

2. M. Peppetta, "South Africa Votes: The Online 'Chatter' [statistics]", Memeburn, 17 May 2011, at http://memeburn.com/2011/05/south-africa-votes-the-online-chatter-statistics/ (accessed 30 October 2011).

3. The 'Arab Spring' of 2011, which saw popular uprisings and regime changes in North Africa and the Middle East was significantly influenced by social media communications. See J. Ghannam, Social Media in the Arab World: Leading up to the Uprisings of 2011 (Center for International Media Assistance, Washington, 2011); J. Pontin, "What Actually Happened", Technology Review, 114, 5, September/October 2011, p 12.

4. R. Marlin-Bennett and E.N. Thornton, "Governance within Social Media Websites: Ruling New Frontiers", in Telecommunications Policy, 2012, at http://www.sciencedirect.com.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/science?ob=ArticleListURL&method=list&ArticleListID=1931692931& sort=r&st=13&view=c&acct=C000062150&version=1&urlVersion=0&userid=4050432&md5= 1e24d3a131f0bfb4cf256cf4c11b2e4a&searchtype=a (accessed 29 March 2012).

5. A.A. Olorunnisola and B.L. Martin, "Influences of Media on Social Movements: Problematizing Hyperbolic Inferences About Impacts", in Telematics and Informatics 2012, at http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0736585312022226/1-s2.0-S0736585312000226-main.pdf?_tid=b0892e71f7c3b676bfc1400a02e15ab0&acdnat=13329924392927a75833edc208f3 db879935ce0143 (accessed 29 March 2012); G.J. Carroll, M.E. Hugo and L.E. Hoffman, "All the News that's Fit to Post: A Profile of News Use on Social Networking Sites", in Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 1, 2012, pp 113-119.

6. F. Grobler and M. Montsho, "Open Toilets Symbolise Lack of Delivery", News24, 13 May 2011, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/Local-Elections-2011/Open-toilets-symbolise-lack-of-delivery-20110513 (accessed 30 October 2011); M. Ndletyana, "Contextual Perspective: 2011 Local Government Elections: Turning of the tide?, Journal of Public Administration, 46 (Special Issue 3.1), pp 1117-1121; X. Mangcu, "Elections and Political Culture: Issues and Trends", Journal of Public Administration, 46 (Special Issue 3.1), pp 1153-1168.

7. National Planning Commission (NPC), "Diagnostic Overview" (Department of the Presidency of South Africa, Pretoria, November 2011), p 20.

8. The Times, 10 May 2011.

9. J.W.N. Tempelhoff, A.S. van Zyl, E.J. Nealer, M. Ginster, S. Berner, I.M. Moeketsi, M. Morotolo, A. Tsotetsi, M.P. Radebe, K. Magape, T.A. Qhena and R. Moabelo, "Environmental Health and the Hydrosphere in Moqhaka Local Municipality, Free State, South Africa", CuDyWat Report 2/2011, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, 2012.

10. For an applied epistemological exposition of the approach see J.W.N. Tempelhoff, "Water History and Transdisciplinarity: A South African Perspective", TD The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 7, 2, December 2011, pp 316-336. For some methodological pointers, see M. Terre Blanche and K. Durrheim, "Histories of the Present: Social Science Research Context", in M. Terre Blanche, K. Durrheim and D. Painter (eds), Research in Practice: Applied Methods for the Social Sciences (UCT Press, Cape Town, 2011), pp 1-15.

11. South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC), Case: WC/20100029, African National Congress Youth League, Dullah Omar Region, Ward 95, Makhaza residents (complainant) and City of Cape Town (respondent). Signed: P Govender, Cape Town, 11 June 2011.

12. Sapa, "Toilets Built without Walls", News24, 21 January 2010 at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/Toilets-built-without-walls-20100121 (accessed 21 October 2011).

13. Sapa, "Open Toilets were Agreed on", News24, 22 January 2010 at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/Open-toilets-were-agreed-on-20100122 (accessed 21 October 2011); Sapa, "Zille: ANC Youth League behind Toilet Saga", Mail & Guardian, October 2010, at http://mg.co.za/article/2010-07-05-zille-anc-youth-league-behind-toilets-saga (accessed 17 November 2011).

14. Sapa, "Open Toilets were Agreed on", News24, 22 January 2010, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/Open-toilets-were-agreed-on-20100122 (accessed 21 October 2011).

15. Sowetan, 17 May 2011.

16. Sapa, "Zille: ANC Youth League behind Toilet Saga", Mail & Guardian, 8 October 2010 at http://mg.co.za/article/2010-07-05-zille-anc-youth-league-behind-toilets-saga (accessed 17 November 2011).

17. H. Zille, "The Wool has been Pulled over your Eyes", Mail & Guardian, 15 October 2010, at http://mg.co.za/article/2010-10-15-the-wool-has-been-pulled-over-your-eyes (accessed 17 November 2011).

18. S. Phaliso, "Police Hauled before Court in Makhaza Toilet Saga", West Cape News, 10 March 2011, at http://westcapenews.com/?p=2809 (accessed 21 October 2011).

19. Sapa, "CT at Crossroads over Toilets", News24, 26 May 2010, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/CT-at-crossroads-over-toilets-20100525 (accessed 21 October 2011).

20. Sapa, "CT at Crossroads over Toilets", News24, 26 May 2010

21. Sapa, "People Angry over Toilet Removals", News24, 31 May 2011, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/People-angry-over-toilet-removals-20100531 (accessed 21 October 2011).

22. Beeld, 17 May 2011.

23. Sapa, "Further Protests over Toilets", News24, 1 June 2010, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/Further-protests-over-toilets-20100601 (accessed 21 October 2011); Sapa, "Toilet Protesters Due in Court", News24, 2 June 2010 at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/Toilet-protesters-due-in-court-20100602 (accessed 21 October 2011).

24. Sapa, "Toilet Protesters Due in Court", News24, 2 June 2010.

25. Sapa, "CT Toilets 'Violated Right to Dignity'", News24, 4 June 2010 at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/CT-toilets-violated-right-to-dignity-20100604 (accessed 21 October 2011).

26. South African Human Rights Commission Report, Case No. WC/2010/0029. African National Congress Youth League, Dullah Omar Region, Ward 95 Makihaza residents (complainant) and City of Cape Town (respondent), Johannesburg, 11 June 2010.

27. Sapa, "Community 'Needs Bullet-proof Toilets'", News24, 4 June 2010, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/Community-needs-bulletproof-toilets-20100604 (accessed 21 October 2011).

28. C. McEwan, "Bringing Government to the People: Women, Local Governance and Community Participation in South Africa", Geoforum, 34, 4, 2003, pp 469-481.

29. H. Mnguni, "Archbishop Enters Toilet Fray", News24, 9 June 2010, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/Archbishop-enters-toilet-fray-20100609 (accessed 21 October 2011).

30. Sapa, "Zille Walks out of 'Toilet' Talks", News24, 24 June 2010, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/Politics/Zille-walks-out-of-toilet-talks-20100624 (accessed 21 October 2011).

31. Sapa, "Zille: ANC Youth League behind Toilet Saga", Mail &Guardian, at http://mg.co.za/article/2010-07-05-zille-anc-youth-league-behind-toilets-saga (accessed 17 November 2011).

32. J.-J. Joubert, "ANC's open Toilet Shame", City Press, 11 July 2010, at http://152.111.1.87/argief/berigte/citypress/2010/07/12/CP/8/JJtoilets.html (accessed 21 October 2011).

33. J-J. Joubert, "ANC's open Toilet Shame", City Press, 11 July 2010.

34. Anon., '"Loo with a View' or a Bucket: Cape Town Community to Choose", Mail & Guardian Online, 27 October 2011, available at http://www.monstersandcritics.com/news/africa/news/article1594418.php/Loo-with-a-view-or-a-bucket-Cape-Town-community-told-to-choose (accessed 18 November 2011).

35. Sapa, "City 'did not Consult Community' on Toilets'", News24, 27 October 2010, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/City-did-not-consult-community-on-toilets-20101027 (accessed 21 October 2011).

36. G. Underhill, "ANCYL Admits to Role in Cape Protest", in Mail & Guardian, 19 November 2011, at http://mg.co.za/article/2010-11-19-ancyl-admits-to-role-in-cape-protest (accessed 17 November 2011).

37. Sapa, "W Cape Toilet Saga Continues in Court", News24, 11 March 2011, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/W-Cape-toilet-saga-continues-in-court-20110311 (accessed 21 October 2011).

38. Phaliso, "Police hauled before court in Makhaza toilet saga", West Cape News, 10 March 2011.

39. Sapa, "Malema Arrives at Cape Court for Toilets Ruling", News24, 29 April 2011, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/Malema-arrives-at-Cape-court-for-toilets-ruling-20110429 (accessed 21 October 2011).

40. Sapa, "City of Cape Town Loses Toilet Case", News24, 29 April 2011, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/City-of-Cape-Town-loses-toilet-case-20110429 (accessed 21 October 2011).

41. Sapa, "DA Accepts Cape Town Toilet Ruling", News24, 29 April 2011, at http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/Politics/DA-accepts-Cape-Town-toilet-ruling-20110429 (accessed 21 October 2011).

42. Sapa, "DA accepts Cape Town toilet ruling", News24, 29 April 2011.

43. Sapa, "HRC Probes Open Toilets in ANC-run Municipality", Mail & Guardian, 8 May 2011, at http://mg.co.za/article/2011-05-08-hrc-probes-open-toilets-in-ancrun-municipality (accessed 25 October 2011).

44. Sapa, "ANC 'Didn't Know' about Toilets: Mantashe", in TimesLive, 9 May 2011, at http://www.timeslive.co.za/local/2011/05/09/anc-didn-t-know-about-toilets-mantashe (accessed 7 February 2012).

45. J. Brits, "Raadslede se Koppe Geëis: Malema, ANC-hoës Veroordeel Moqhaka se Oop Toilette", Volksblad, 11 May 2011, at http://152.111.11.6/argief/berigte/volksblad/2011/05/11/VB/1/krviljoen1-V2-02.html (accessed 25 October 2011).

46. S. Evans and I. Rawoot, "ANC Mayor Stood to Profit from Open Toilets", Mail & Guardian, 11 May 2011, at http://mg.co.za/article/2011-05-11-toilet-town-anc-mayor-profited-from-open-lavatories (accessed 21 October 2011); J. Brits, "Eerste Burger 'Las vir die ANC': JKL Eis Kop van Moqhaka se Mokgosi", Volksblad, 12 May 2011, at http://152.111.11.6/argief/berigte/volksblad/2011/05/12/VB/1/krspoeg.html (accessed 25 October 2011).

47. S. Tau, "Toilets 'Violate Human Rights'", The Citizen, 16 May 2011, at http://www.citizen.co.za/citizen/content/en/citizen/local-news?oid=195001&sn=Detail&pid=146827&Toilets-%E2%80%98violate-human-rights%E2%80%99 (accessed 21 October 2011).

48. In discussion with some of the Gatvol leaders, it was stressed that the initiative was not aimed at strengthening party political issues. The focus was more on articulating the demands of civil society for proper service delivery. See Tempelhoff et al., "Environmental Health and the Hydrosphere in Moqhaka", pp 7 and 11.

49. See J.W.N. Tempelhoff et al., "Environmental Health and the Hydrosphere in Moqhaka".

50. J. Brits, "Toilet-woede laat Hoë Vug", Volksblad, 14 May 2011, at http://52.111.11.6/argief/berigte/volksblad/2011/05/14/VB/1/krrou.html (accessed 25 October 2011).

51. J. Brits, "Vrou Gooi Kombers oor as sy Toilet Besoek: Inwoners Hier Moeg Gesukkel", Volksblad, 13 May 2011, at http://152.111.11.6/argief/berigte/volksblad/2011/05/13/VB/2/krkroontoil-V2-02.html (accessed 25 October 2011).

52. Brits, "Vrou Gooi Kombers oor", Volksblad, 13 May 2011.

53. Tau, "Toilets 'Violate Human Rights'", The Citizen, 16 May 2011.

54. P. Steyn, "Fokus Eerder op Welslae, vra ANC Hoog in die Nood: Vinger Wys na Burgemeester se Man in Toilette-debakel", Voksblad, 13 May 2011, at http://152.111.11.6/argief/berigte/volksblad/2011/05/13/VB/2/psspoellatrines-VB.html (accessed 25 October 2011).

55. E. van Wyk, "Open Toilets the Responsibility of Sexwale's Department, Says Minister", City Press, 16 May 2011, at http://152.111.1.87/argief/berigte/citypress/2011/05/16/CP/2/evtoilet1.html (accessed 21 October 2011).

56. Editorial comment, "Toilette Word nou Politieke Speelbal", Volksblad, 12 February 2011, at http://152.111.11.6/argief/berigte/volkssblad/2011/05/12/VB/4/art11.html (accessed 25 October 2011).

57. A. Boraine, "Designing Better Sanitation Services in Informal Settlements", Cities for People, at http://www.andrewboraine.com/2011/10/designing-better-sanitation-services-in-informal-settlements-cape-towns-r138m-special-jobs-creation-programme-has-real-potential-to-add-impetus/ (Accessed 30 October 2011).

58. J. Gavin, "SJC to Host Cape Town Sanitation Summit", Social Justice Coalition, at http://www.sjc.org.za/posts/sjc-to-host-cape-town-sanitation-summit (accessed 30 October 2011).

59. O. Molathlwa, "Toilet Stink Still Hanging in the Air", Sowetan Live, 5 August 2011, at http://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/2011/08/05/toilet-stink-still-hanging-in-the-air (accessed 6 December 2011).

60. M. Thakudi and N. Seleka, "Bank Pledges R7million to Kill Toilet Stink", Sowetan, 18 November 2011, at www.sdinet.org/media/upload/documents/SowetanNov2011.pdf (accessed 5 December 2011); T. Geldenhuys, "Toilette Staan Steeds Oop", Kroonnuus, 20 November, 2011, at http://152.111.11.6/argief/berigte/volksblad/2011/11/22/KN/3/kntoilet.html (accessed 6 December 2011).

61. P. du Toit, "Verslag oor Stadsrade Skok Cabinet: Opstellers Moet dit Oordoen", Volksblad, 11 May 2011, available at http://152.111.11.6/argief/berigte/volksblad/2011/05/12/VB/2/polpdt1005 1634.html (accessed 23 October 2011).

62. R.D. Russon, "Ten Years of Democratic Local Government Elections in South Africa: Is the Tide Turning?", Journal of African Elections, 10, 1, June 2011, p 78.

63. M. Ndletyana, "Independents vs the Ruling Party: A Case of Maletswai Municipality," Journal of Public Administration, 46, 3.1, September 2011, pp 1210-1228.

64. R.D. Russon, "Ten Years of Democratic Local Government Elections", pp 81-82.

65. E. van Wyk, "How the ANC Won the PR Loo War", City Press, 15 May 2011, at http://152.111.1.87/argief/berigte/citypress/2011/05/16/CP/2/evtoilet3.html (accessed 21 October 2011).

66. Sapa, "Malema: Heads Must Roll for New Open Toilets Fiasco", Mail & Guardian, 10 May 2011, at http://mg.co.za/article/2011-05-10-malema-heads-must-roll-for-open-toilets (accessed 10 May 2011). '

67. Evans and Rawoot, "ANC Mayor Stood to Profit from Open Toilets", Mail & Guardian, 11 May 2011, avaiable at http://mg.co.za/article/2011-05-11-toilet-town-anc-mayor-profited-from-open-lavatories (accessed 21 October 2011); Sapa, "ANC: We Knew about Mayor's Links to Open Toilets", Mail & Guardian, 12 May 2011, at http://mg.co.za/article/2011-05-12-anc-we-knew-about-mayors-links-to-opentoilets-contract (accessed 21 October 2011).

68. Anon., "ANC: Stirred but Not Shaken", City Press, 15 May 2011, at http://152.111.1.87/argief/berigte/citypress/2011/05/14/CP/26/TiatjaragMay15.html (accessed 21 October 2011).

69. P. de Vos, "Notes on the 'Toilet Election'", in Constitutionally Speaking, 11 May 2011, at http://constitutionallyspeaking.co.za/notes-on-the-toilet-election/ (accessed 30 October 2011).

70. Editorial: "Toilette word Nou Politieke Speelbal", Volksblad, 11 May 2011, at http://152.111.11.6/argief/berigte/volksblad/2011/05/12/VB/4/art11.html (accessed 22 October 2011).

71. Editorial comment, "Viable Opposition is Good for Democracy", South African Journal of Science, 107, 5/6, 2011, p 1.

72. Grobler and Montsho, "Open Toilets Symbolise Lack of Delivery", News24, 13 May 2011.

73. De Vos, "Notes on the 'Toilet Election'".

74. S. Robins, "Toilets that Became Political Dynamite", Cape Times, 27 June 2011, at sun025.sun.ac.za/portal/page/portal/Arts/.../SR%20article.pdf (accessed 30 October 2011).

75 Robins, "Toilets that became political dynamite", Cape Times, 27 June 2011.

76. Centre for Law and Social Justice, "Statement by the Social Justice Coalition", at http://writingrights.org/2011/05/13/from-makhaza-to-moqhaka-end-the-toilet-wars-why-is-the-south-african-human-rights-commission-quiet/ (accessed 21 October 2011).

77. Grobler and Montsho, "Open Toilets Symbolise Lack of Delivery", News24, 13 May 2011

78. Grobler and Montsho, "Open Toilets Symbolise Lack of Delivery", News24, 13 May 2011.

79. iTunes podcast, R. Harrison, "Hannah Arendt: A Conversation with Karen Feldman", Parts 1 and 2, Entitled opinions, 15 May 2007.

80. See A. Lawless, Numbers and Needs: Addressing Imbalances in the Civil Engineering Profession (SAICE, Halfway House, 2005).

81. D.A. McDonald, "The Bell Tolls for Thee: Cost Recovery, Cutoffs, and the Affordability of Municipal Services in South Africa", Municipal Services Project, Queens University, Canada, 2002, at ftp://healthlink.org.za/pubs/localgov/mspreport.pdf (Accessed 4 December 2011).

82. R. Mathekga and I. Buccus, "The Challenge of Local Government Structures in South Africa: Securing Community Participation", in Critical Dialogue: Public Participation in Review (IDASA, Cape Town, 2006), pp 11-17.

83. T. Lodge, "The South African Local Government Elections of December 2000", Politikon, 28, 1, December 2000, pp 21-46; Anon., "Political Participation", in B. Klandermans, M. Roefs and J. Olivier (eds), The State of the People: Citizens, Civil Society and Governance in South Africa, 1994-2000 (HSRC, Pretoria, 2001), p 227.

84. Anon., "In Conversation with Udesh Pillay: Key Issues in the 2011 Government Elections", HSRC Review, 9, 1, March 2011, at http://www.hsrc.ac.za/HSRCReviewArticle-231.phtml (accessed 19 November 2011).

85. T. Lodge, "South African Politics and Collective Action, 1994-2000", in Klandermans, Roefs and Olivier (eds), The State of the People, p 15.

86. Lodge, "The South African Local Government Elections of December 2000", p 27.

87. M. Ndletyana, "Municipal Elections 2006: Protests, Independent Candidates and Cross-border Municipalities", in S. Buhlungu, J. Daniel, R. Southall and J. Lutchman (eds), State of the Nation: South Africa 2007 (HSRC, Cape Town, 2007), p 102.

88. Lodge, "The South African Local Government Elections of December 2000", p 43.

89. Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF), A History of the First Decade of Water Service Delivery in South Africa, 1994-2004: Meeting the Millennium Development Goals (DWAF, Pretoria, n.d. c. 2006), p 15.

90. A.K.M. Hoque and Z. Worku, "The Cholera Epidemic of 2000/2001 in KwaZulu-Natal: Implications for Health Promotion and Education", Health SA, 10, 4, December 2005, pp 66-74; L. Mudzanani, M. Ratsaka-Mathokoa, L. Mahlasela, P. Netshidzivhani and C. Mugero, "Cholera", South African Health Review, 2003/2004, p 263; D. Hemson. "Easing the Burden on Women? Water Cholera and Poverty in South Africa", in D. Hemson, K. Kulindwa, H. Lein and A. Mascerenhas, Poverty and Water: Explorations of the Reciprocal Relationship (Zed Books, London and New York, 2008), pp 152-156.

91. Ndletyana, "Municipal Elections 2006", p 102.

92. A. Habib, "State-Civil Society Relations in Post-apartheid South Africa"; and D. Atkinson, "The State of Local Government: Third Generation Issues", both in J. Daniel, A. Habib and R. Southall (eds), State of the Nation: South Africa 2003-2004 (HSRC, Cape Town, 2003), pp 227-241 and 118- 140 respectively.

93. N. Nleya, L. Thompson, C. Tapscott, L. Piper and M. Esau, "Reconsidering the Origins of Protest in South Africa: Lessons from Cape Town and Pietermaritzburg", Africanus, 41, 1, pp 14-29.

94. Associated Press, "Protests Turn Violent in South Africa", The New York Times, 15 October 2009, at http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2009/10/15/world/AP-AF-South-Africa-Protest.html?scp=3&sq=protest%20south%20africa&st=cse (accessed 15 October 2009); B. Bearak, "South Africa's Poor Renew a Tradition of Protest", The New York Times, 6 September 2009, at http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/07/world/africa/07protests.html?scp=1&sq=protest+and+south+africa&st=nyt (accessed 6 September 2009 and 13 October 2009); D. Smith, "Anger at ANC Record Boils over in South African Townships", Guardian.co.uk, 22 July 2009 at http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/jul/22/south-africa-protests (accessed 13 October 2009); A.D. Smith, "Zuma Pleads as Protests Sweep the Townships", Guardian.co.uk, 26 July 20009, at http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/jul/26/jacob-zuma-township-rally-kwazulunatal (accessed 13 October 2009); J. Clayton, "Foreigners Flee as Violence Re-ignites in South African Townships", Timesonline.co.uk, 25 July 2009, at http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/africa/article6726891.ece (accessed 14 October 2009).

95. J. Karamoko, "Service Delivery Protests: Less Frequent, More Violent", Local Government Bulletin, 13, 3, September 2011, pp 10-13; H. Loubser, "Munisipale Betogings Gaan nie Sommer Wyk nie", Volksblad, 30 October 2011, at http://www.volksblad.com/In-Diepte/Nuus/Munisipale-betogings-gaan-nie-sommer-wyk-20111030 (accessed 7 November 2011).

96. B.-A. Mngxitama, "Tatane's Death Underlines Need for Government to deliver", Sowetan Live, 19 April 2011, at http://www.sowetanlive.co.za/columnists/2011/04/19/tatane-s-death-underlines-need-for-government-to-deliver (accessed 21 October 2011); T.S. Maluleke, "Meet Andries. He Died Yesterday", Mail & Guardian: Thought Leader, 15 April 2011, at http://www.thoughtleader.co.za/tinyikosammaluleke/2011/04/15/meet-andries-he-died-yesterday/ (accessed 21 October 2011).

97. K. Tissington, M. Dettmann, M. Langford, J. Dugard and S. Conteh, "Water Services Faultlines: An Assessment of South Africa's Water and Sanitation Provision across 15 Municipalities (CALS, COHRE and NCHR, Johannesburg, 2008).

98. C. Gouws, I. Moeketsi, S. Motloung, J. Tempelhoff, G. van Greuning, and L. van Zyl, "SIBU and the Crisis of Water Service Delivery in Sannieshof, North West Province", TD The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 6, 1, July 2010, pp 29-30.

99. DWA, Strategic Overview of the Water Sector in South Africa, 2010 (DWA, Pretoria, 2010), p 29-34; Press release: V. Qinga, "Service Delivery Challenges Immense but Past Achievements Lay a Solid Foundation for New Councils", issued by Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, Pretoria, 26 May 2011, at http://www.dplg.gov.za/index.php/news/173-press-a-media-releases/220-service-delivery-challenges-immense-but-past-achievements-lay-a-solid-foundation-for-new-councils.html (accessed 18 November 2011).

100. Section 24, (in the Bill of Rights) Republic of South Africa (RSA), Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act, No. 108 of 1996.

101. See, Statistics South Africa (SSA), General Household Survey 2010, Statistical Release PO318 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 2011).

102. See Anon., "Gatvol Kroonstad" at http://www.facebook.com/GatvolKroonstad (accessed 30 March 2012).

103. See Anon., "Mobilitate: A Better South Africa", at http://www.mobilitate.co.za/ (accessed 30 March 2012).

104. See V. Munnik, V. Molose, B. Moore, J. Tempelhoff, I. Gouws, S. Motloung, Z. Sibiya, A. van Zyl, P. Malapela, B. Buang, B. Mbambo, J. Khoadi, L. Mhlambi, M. Morotolo, R. Mazibuko, M. Mlambo, M.I. Moeketsi, N. Qamakwane, N. Kumalo and A. Tsotetsi, "Draft Consolidated Report: The Potential of Civil Society Organisations in Monitoring and Improving Water Quality (Mvula Trust, Braamfontein, for the Water Research Commission, October 2011).

105. See The Mvula Trust at http://www.mvula.co.za/ (accessed 20 October 2011).

106. Faber & Faber, London, 1972.

107. J.W.N. Tempelhoff et al., "Environmental Health and the Hydrosphere in Moqhaka", pp 64-68.

108. Circa. 1945. Reprinted by Viking Press, New York, 1986.

109. Heinemann, London, 1954.

110. J.W.N. Tempelhoff et al., "Environmental Health and the Hydrosphere in Moqhaka", pp 58.

111. J.W.N. Tempelhoff et al., "Environmental Health and the Hydrosphere in Moqhaka", pp 85-87.

112. A. van Zyl, "Collaborative Transboundary Water Quality Monitoring: A Strategy for Fezile Dabi District Municipality and its Neighbours", MA dissertation, NWU (Vaal), 2012.

113. J.W.N. Tempelhoff et al., "Environmental Health and the Hydrosphere in Moqhaka", pp 87-91.

114. C. Pohl, L. van Kerkhoff, G. Hirsch and G. Bammer, "Integration" in G. Hirsch Hadorn, H. Hoffmann-Riem, S. Biber-Klemm, W. Grossenbacher-Mansuy, D. Joye, C. Pohl, U. Wiesmann and E. Zemp (eds), Handbook of Transdisciplinary Research, (Springer, Bern, 2008), pp 411-424.