Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Historia

versão On-line ISSN 2309-8392

versão impressa ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.56 no.2 Durban Nov. 2011

ARTICLES

The Union of South Africa censuses 1911-1960: an incomplete record

Die Unie van Suid-Afrika sensusse: 'n onvolledige rekord

A.J. Christopher

ABSTRACT

Censuses represent a major government enterprise to gather useful information on the population of the country to assist in the administration. The establishment of the Union of South Africa required the creation of a new integrated census system. Initially colonial precedents were followed, but distinctive features, most notably the racial bias in statistical collection and reporting, intruded. The two World Wars and the depression also negatively impacted upon the conduct of the censuses and the tabulation and publication of the results. Indeed, four of the ten Union censuses only described the White population in the country, while substantial sets of collected data were never tabulated and published. Moreover, after the first census in 1911, different questionnaires were supplied to various racial groups and most of the statistics tabulated for the majority of the population were relegated to brief separate reports or summary tables, following the White figures. The censuses therefore failed to gather and present comprehensive and comparable information upon the entire population, leading to significant gaps in the statistical record in the Union period.

Keywords: South Africa; Commonwealth; dominion; administration; delimitation; classification; tabulation; census; questionnaires; information; statistics; population; demography; identity; race; religion; nation; nationality; ages; occupations.

OPSOMMING

Sensusse verteenwoordig 'n groot regerings onderneming om nuttige inligting in te samel oor die bevolking van die land om die administrasie by te staan. Met die vestiging van die Unie van Suid-Afrika was dit nodig vir die skepping van 'n nuwe geïntegreerde sensus stelsel. Aanvanklik was koloniale presedente gevolg, maar die kenmerkende eienskappe, veral die rasse-vooroordeel in statistiek versameling en verslagdoening het later ingedring. Die twee wêreldoorloë en die depressie het ook 'n negatiewe uitwerking op die uitvoer van die sensusse en die tabulering en publikasie van die uitslae gehad. Inderdaad vier van die tien Unie sensusse beskryf slegs die wit deel van die bevolking, terwyl baie van die versamelde data was nooit getabuleer en gepubliseer nie. Buitendien, ná die eerste sensus in 1911, was veelsoortige vraelyste aan verskillende rassegroepe gegee, en die meeste van die statistieke wat vir die meerderheid van die bevolking ingepalm was, het slegs in kort, afsonderlike verslae of opsomming tabelle beland. Die sensusse, is dus nie omvattende nie en die inligting is nie vergelykbaar van die hele bevolking nie en dus het dit gelei tot groot leemtes in die statistiese rekord van die Unie-tydperk.

Sleutelwoorde: Suid-Afrika; Statebond; heerskappy; administrasie; afbakening; klassifikasie; tabelle; sensus; vraelyste; inligting en statistieke; bevolking; demografie; identiteit; ras; godsdiens; nasie; nasionaliteit; ouderdomme; beroepe.

Introduction

The census is one of the most intrusive and comprehensive investigations undertaken by the state in its quest for information concerning the population which it controls and serves.1 The information sought is more than a mere headcount. It reflects the official need for statistics on a wide range of human activities and attributes, in order to execute the functions of the modern bureaucratic state because it came into being in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.2 Census questionnaires require not only purely demographic statistics on the number of people by sex, age and marital status, but also economic information on education, occupation, and income and most contentiously on questions of identity including race, language, religion and nationality.3 Indeed it was the census authorities who throughf the collection and tabulation of vast quantities of individual items of data, provided: "the descriptions which 'speak to power' with 'useful' information".4 In order to make the data intelligible to the state bureaucracy it was necessary to simplify and to classify the population into defined categories or groups, for which the census authorities also possessed the prerogative of naming.5

The national census organisation constitutes a major and powerful governmental enterprise, which has become the subject of enquiry in itself. This is particularly the case in the United States, where the uninterrupted sequence of decennial enumerations which began in 1790, has been the object of intensive scrutiny, particularly in its handling of the issue of race.6 It has been noted that the census was one of the key elements in the definition of the modern nation-state through the collection of unified data and the adoption of common classification schemes, paralleling the survey and mapping of the territory of the state, whether nineteenth-century England or post-colonial Asia.7 Similar developments have also been identified in states traditionally organised on confessional lines undergoing modernisation in the nineteenth century.8 In the twentieth century the Soviet census organisation played a vital part in the development of the category "nationality" and the forging of a new nation.9 Similarly in Nazi Germany and its occupied countries the census was a key to the identification and monitoring of people, most notably the Jewish population.10 More recently the censuses have played a significant role in the definition of the state and nation in the post-Soviet republics seeking to establish their own separate identities.11

The state's quest for information was as intense in the colonies as in the metropolitan countries.12 It has been suggested that numbering and classification were essential parts of the colonial project.13 Indeed, in the colonies census commissioners were able to conduct enquiries into topics, notably those of identity, which were not possible in the United Kingdom. Furthermore, the census was not a neutral observer, but helped to create a new society, through the imposition of statistical order upon the population.14 It has been suggested that:

Individuals find themselves firmly fixed as members in various groups of a particular dimension and substance. Thus the census imposes order and order of a statistical nature. In time the creation of a new ordering of society will act to reshape that which the census sought to merely describe.15

Within the British Empire, the role of the census in the demographic ordering of the population of India has been extensively examined.16 The presence of a substantial literate indigenous bureaucracy which was essential to the pursuit of this level of documentation as it was in the United Kingdom and the other dominions. However, it was lacking in the African colonies. Thus British colonial censuses in Africa did not achieve anything comparable with those of India. As late as 1946, the Colonial Office complained about the lack of enumerations of the African population.17 Detailed analysis demonstrated how far most of the African colonial censuses were from a comprehensive survey suggested as the colonial ideal.18 On the other hand the censuses held in the West Indies did approach the inclusiveness sought in the United Kingdom.19 Nevertheless, it was with the other dominions that South Africa might be compared, and with which its statistical officers shared experience and Commonwealth conferences. In this respect the record was mixed. The census of Canada was a comprehensive enterprise which had included the indigenous population as part of the national inventory since the nineteenth century.20 That of Australia excluded the Aboriginal population from the census returns under a constitutional provision until 1967.21 In New Zealand, separate Maori censuses with separate questionnaires had been conducted until 1951 and separate reports continued thereafter.22

The census in South Africa has received comparatively little attention beyond the use of its data. The sequence of censuses was irregular and the coverage unsystematic during the nineteenth century. The Cape of Good Hope conducted the first modern scientific census in 1865, following the principles laid down by the British Colonial Office and repeated the exercise in 1875 and 1891.23 The Orange Free State followed in 1880 and 1890, copying many of the features of the Cape of Good Hope.24 The South African Republic (Transvaal) followed in 1890.25 However, the enumeration was restricted to the White population.26 Finally, in 1891 Natal conducted a partial enumeration.27 The information demanded varied substantially and the final reports ranged from a few pages to several hundred. After the South African War of 1899-1902, all the colonies undertook censuses in April 1904, but although broad coordination took place the results were presented according to the views of the four individual census commissioners.28 The detailed coordination of censuses evident in pre-federation Australia was therefore not in evidence in South Africa.29 The establishment of the Union of South Africa as a British dominion in 1910 necessitated a new start to enumeration in the country and the statistical definition of the new state and ordering of its population through the census. The sequence of ten censuses in the Union period constitutes a distinctive set before new political imperatives produced different configurations of state and nation. It is proposed first to examine the changing scope and published record of the Union censuses. This is followed by an assessment of the problems associated with the statistical record, particularly with regard to the issues of identity and other attributes of national significance. Finally, an attempt is made to gather the diverse threads together.

The form of the census

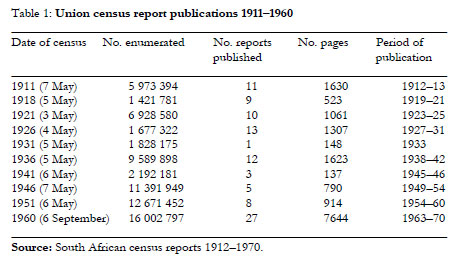

The constitution of the Union of South Africa provided for the provincial allocation of the seats in the House of Assembly to be re-determined every five years. In order to achieve this outcome, a population census was required before the appointment of each delimitation commission. The Census Act of 1910 is therefore one of the founding pieces of legislation of the new state and an integral part of the legislative process until the link between the census and the allocation of seats was ended in the 1950s. A separate Census Office was established in 1910 and its Director was given responsibility for the conduct of the quinquennial census, beginning in 1911.30 The questionnaire was in large measure designed in conformity with the requirements of the "Census of the British Empire 1911" envisaged by the Colonial Office in London.31 Although synchronisation with the census in the United Kingdom had been sought, the Census Director in Pretoria had deemed the 3 April date to "be too early in the season" and settled upon the 7 May 1911.32 All but the last Union census were to adopt a date in early May based on this precedent and minor symbolic break with the use of the British census date (see Table 1).

As a result of the outbreak of the First World War the next census was rescheduled to 1918 and confined to an enumeration of Whites only. The first Delimitation Commission, appointed for delimiting constituencies for the first House of Assembly in 1910 had employed the 1904 census results, while the second in 1913 had made use of the first Union census of 1911.33 The 1918 census was required by the Third Delimitation Commission which only reported in 1919.34 The expedient was possible because only the numbers of Whites were used in the calculations for the apportionment of seats between the provinces. The actual delimitation within provinces was determined by the numbers registered on the voters' rolls, which in the case of the Cape of Good Hope included a substantial number of Africans and Coloureds. The exercise effectively reduced the value of their votes relative to exclusively White voters of the Transvaal and Orange Free State.

The 1921 census was a full enumeration of the entire population, held at virtually the same time as the remainder of the British Empire. The Report of the Dominions Royal Commission had suggested in 1917 a greater degree of uniformity in data collection within the Empire and proposed the establishment of a British Empire Statistical Bureau. A conference of statistical officers from Commonwealth countries convened in London in 1920 to examine the project and coordinate programmes for the 1921 census.35 The diversity of opinions between the United Kingdom on the one hand and the dominions on the other precluded any tangible outcome. Nevertheless, the conference did result in a high degree of coordination and the adoption of some joint, mainly British, classification schemes. In Pretoria, however, differentiation was evident as different questionnaires were devised for the different population groups, even separate questionnaires for Africans living in the legally scheduled African rural areas and those living in the remainder of South Africa, and so uniformity within the country, let alone the Empire was lacking.36

The 1926 census was planned and carried out as a whites-only exercise, following the precedent set in 1918.37 The results were incorporated into the Report of the Fifth Delimitation Commission.38 The 1931 census was planned as a part of the Census of the British Empire with a comprehensive enumeration of the total population. However, in early 1931 it was scaled down to a whites-only initiative as a result of the economic crisis afflicting the country.39 It might be noted that most of the planning for a full enumeration had been done and the larger infrastructure necessary for its execution had been set in place. In 1936 it was decided that a full enumeration would be conducted rather than wait for 1941. The principle of racially differentiated questionnaires was continued from 1921 and was to be retained for all subsequent censuses.40

The Second World War led to the cancellation of the 1941 census in the United Kingdom and most British Commonwealth countries. In South Africa it was reduced to another whites-only exercise for the Eighth Delimitation Commission.41 As a result, the 1946 census was upgraded to a full enumeration.42 This was repeated in 1951 as South Africa returned to a pattern of virtual synchronisation with those in the United Kingdom and the rest of the British Commonwealth.43 Constitutional changes in the 1950s resulted in the removal of those who were not classified as White from the voters' rolls and the removal of the link between the census and the delimitation process. As a result, the projected 1956 census did not take place. Finally the date of the projected 1961 census was changed from the northern hemisphere Spring month of May, to the southern hemisphere Spring month of September 1960.44 The adoption of the end of the decade year emulated the nineteenth-century republican censuses in the Orange Free State and South African Republic, themselves following the precedent set by the American republic and contrary to the British Empire's adoption of the first year of the decade for enumerations.

It is through the publication record of the censuses that they are generally known and used. It should be emphasised that the South African censuses, unlike those of the United Kingdom have left no extensive record of manuscript returns. The enumerators' summary books are all that remain after the destruction of the individual completed questionnaires.45 Even here confidentiality rules preclude their public consultation. It is in the printed record that the censuses are known and there can be no reworking of the results because a question was not as the researcher would have asked it or the statistics were tabulated in another manner. Government officials, statisticians and others in each age asked its particular questions and tabulated the results as the census directors thought most suitable to answer the questions of that date. The publications therefore have to be read in that light.

The first observation is that the published record is very diverse and variable. In volume, the results were until 1963 published as parliamentary papers and thereafter as statistical reports in the same format. The number of such publications per census varied from one for the 1931 census to 27 for the final 1960 census. The number of pages covered ranged from 137 to 7644. Within such a range, the topics covered and the detail and scale at which they were covered varied substantially.

A feature of the early (1911-1926) censuses was the publication of a general report, where the Census Director presented an overview of the conduct of the exercise and commented upon the subjects and trends which he thought to be noteworthy. Such general reports had accompanied the British censuses since 1861.46 The single volume 1931 census report sufficed for that enumeration. However, the general report for the 1936 census was postponed because of the outbreak of the Second World War and was never written.47 After 1945 the practice was not revived. Indeed the introductory sections of the published volumes were often merely technical and repeated verbatim in each volume for a census sequence. Nevertheless, the general reports which were published remain significant demographic publications. That produced for the 1921 census extended to some 417 pages illustrated with numerous maps and diagrams.48 Some commentary was incorporated in individual reports on the 1936 census and subsequent censuses, but on the whole it was brief and lacked the comprehensive overviews offered by the general reports.

It is noticeable that the time span for publication increased significantly during the Union period. The results of the 1911 census, including the general report, were published within two years of the enumeration. Paradoxically, the introduction of tabulating machines for the 1918 census delayed the production of results, because the data had to be punched by hand onto cards before the calculations could take place. Thus the production of the 1921 census publications took four years. That for 1926 took five years and 1936 took six. After the Second World War the publication of the 1946 and 1951 censuses became linked, as some tables for 1946 only appear with the 1951 results. Speed did not improve with the 1951 census results taking nine years to appear while the volumes on occupations and incomes were never completed. As a result a set of ten per cent sample volumes were produced for the 1960 census for use prior to the publication of the definitive figures, which was only completed in 1970.49 Although 27 volumes were issued for the 1960 census, most of the additional space was taken with new cross-tabulations, including 14 volumes for individual urban areas. It is remarkable that the results of the 1960 census were mostly published on the basis of the four race groups, with comparatively few pages (5.0 per cent) of tables covering the entire population, compared with 39.9 per cent exclusively for the White population, 21.6 per cent for the Coloured population, 17.4 per cent for the Asian population and only 16.2 per cent for the majority African population.50 An additional special report attempted to draw the sequence of censuses together on a common geographical framework.51

Race, religion, language and nationality

The most important identity attribute recorded in the census was race, for it was against race that all other attributes were cross-tabulated. Indeed, for most censuses it determined which questionnaire a person filled in, or even whether they were counted at all. Racial science in its various forms dominated South African politics in the Union period and this was manifested in the census.52 At Union the Director of Census was faced with the problem of devising a race classification to suit the new state.53 The Registrar General of England and Wales in his report on the 1901 census of the British Empire was of little assistance as he stated that: "The scientific description of Races can hardly be brought within the scope of a Census Report, more specially as there appears to be no standard classification of the varieties of the human species".54 This did not mean that there had not been a vigorous debate within the British ethnographic and anthropological communities to produce one.55 Indeed it had not deterred colonial and dominion census commissioners from devising their own to reflect each countries' circumstances.56 In doing so they had to formulate classification schemes which could be readily and consistently applied by the enumerators, often of diverse backgrounds, who had neither a training in physical anthropology nor the time to undertake detailed enquiries into a person's background. The Cape of Good Hope had devised a six-fold classification reflecting the complexities of that society.57 However, it included several anomalies, and was criticised as being "by no means scientific" and requiring simplification by the time of the 1904 census.58 It included as separate groups, Cape Malays, based on religion, and "Fingos", based on a particular ethnicity. In addition the "Hottentot" (Khoisan) group was considered to have largely integrated with the Cape Coloured group by the end of the nineteenth century.59 In Natal, the Indian population was separately enumerated, while in the Transvaal the Cape Coloured population was separated from other groups.

The Director of Census therefore exercised his prerogative to define the groups and adopted a simple three-fold classification in 1911 to remove the intricacies and overlaps of individual colonial schemes. The groupings were "European or White", "Native" or "Bantu", and "Mixed and Coloured".60 In this census the distinction between Europeans and "Others" was made in many tables, where the statistics for the Native and Coloured groups were amalgamated. The number of groups was increased to four in 1921 with the introduction of a separate Indian group.61 This was necessitated by the request for information on the Indian population by the Government of India and to monitor progress in the Indian repatriation programme conducted by the South African government. Owing to the differences in questionnaires for each group from 1921 onwards the broad European-Other dichotomy was not presented in tabular form in the post-1911 era, although separate "Non-European" volumes were published. This fourfold division was considered by the Director of Census and Statistics at the time as a burden which: "sometimes tends to throttle every bit of work we do which concerns our population".62 In 1951 the Cape Malays were reintroduced as another group in response to the requirements of the Population Registration Act of 1950.63 However, their numbers (62 807) were too small to warrant the additional time and space required for their tabulations and they were merged with the Coloured population for most tables; the distinction was not raised again.

In view of the significance of race in all aspects of society, the basic classification was retained and codified in 1950. Nomenclature proved as problematical in South Africa as it did in other countries.64 The boundaries of the groups were not clear and the definitions often did little to assist the process of classification. In 1911 there was a contradiction between the terms "Native" and "Bantu", which affected the indigenous inhabitants of the Western Cape, the Khoisan (Bushmen and Hottentots), who did not originally speak a Bantu language. They had been separately listed in the earlier Cape censuses. Thus the enumerators in the town of Beaufort West classified 920 persons as "Natives", but subsequently their supervisor reduced this to 361, assigning the remainder to the "Mixed and Coloured" category.65 In 1936 the definition of the boundaries between the groups, particularly for Europeans, assumed greater significance, with official anxiety over people of mixed parentage "passing over the line" and being reclassified. Census enumerators were instructed that: "discreet inquiries should be made locally to ascertain whether a person of doubtful descent is looked upon locally and received by his European neighbours as a European".66 In 1936 an attempt was made to distinguish the various groups contributing to the Coloured population, indicating that 11.3 per cent were of Hottentot origin compared with only 4.4 per cent as Cape Malay.67 The Chinese community was virtually invisible in census terms, as they were in most other respects.68

The 1951 census marked a significant change in approach as it: "formed the basis of the Population Register established under the Population Registration Act" of 1950.69 Definitions were thus legislated, rather than reached by self-identification or acceptance by other members of a group. Ultimately it was the difference in definition between physical appearance and social acceptance which became legally significant under the enforcement of the Group Areas Act, which prompted the legal opinion that race classification was an attempt "to define the indefinable".70

Religion is an important element in self-definition and national identity. Although the census of Great Britain had only attempted an enquiry into religious observance once in 1851, Ireland and many of the colonial censuses did probe religious adherence.71 Religion therefore appeared as a topic in the pre-Union censuses and was included in the list indicated by the Registrar General for inclusion in 1911.72 In South Africa the religious census was significant because it provided an indication of broad group and hence political allegiance, within the White population, in the absence of a language question. In particular the identification of the various branches of the Dutch Reformed Church approximated to the extent of the Afrikaner population and it was this constituency which dominated politics throughout the Union period.73

It is notable that the census sought individual denominations, but the responses were usually inadequate for reliability in this respect. Thus in 1911, although the three main branches of the Dutch Reformed Church were identified in the detailed tables, they were frequently combined because the term "Gereformeerd" was applied somewhat generally.74 Similarly, the schisms within the Anglican and Methodist churches were generally difficult to tabulate and combined figures were produced. The concentration upon the Christian denominations reflected the relative importance attributed to the White population. In contrast, in 1911 some 73.7 per cent of the African population was assigned to the "no religion" category indicating a complete lack of interest in indigenous belief systems. Initially only the "mission" churches were accepted as Christian in the returns. However, in 1936 the "separatist churches" were listed, but not individually named, for the first time, and by 1960 they accounted for 21.2 per cent of the African population.75 Some 3.5 million (32.1 per cent) were still classified as "other and unspecified" in 1960. Thus the Union censuses failed to recognise and monitor the development and complexity of the accommodation between indigenous belief systems and Christianity which took many forms and provided an alternative form of identity.76 Other religions received passing mention, with no investigation of their diversity, as the majority of Moslems and Hindus were not White.

Language is one of the most significant criteria in the definition of a nation or nationality. It is scarcely surprising that the census undertook an enquiry into aspects of language. In 1911 there was no guidance from the Registrar-General on the subject. Indeed the subject had been neglected in British colonial censuses and in the United Kingdom it was only the survival of the peripheral Celtic languages which was the subject of any enquiry. However, the Dominion of Canada recognised the significance of language in the political accommodation of the French and English speakers and incorporated elaborate questions in the census to test the development of the accommodation.77 The quest for "national origin" supplied the gap in the information, as the religious question in that country did not, in the presence of so many Irish immigrants. A parallel probe could be discerned in the analysis of Dutch and English speakers in the White community in South Africa, where initially a surrogate question (religion) had been asked in place of a language question.

In 1918 the White population was asked a question about an individual's ability to speak the two official languages, English and Dutch, or later Afrikaans.78 In this respect it probed the extent of bilingualism as a measure of the evolution of a common South African White nation. The results indicated that 42.1 per cent could speak both. The figure gradually rose to 64.4 per cent by 1936.79 The question revealed little about the relative sizes of the two language groups, because the majority of monoglots were English speakers.

The question of home language was only posed in 1936 for the first time. The questionnaire allowed the response "Afrikaans and English" for households where both were spoken, thereby blurring the intent of the enquiry. The number of such responses was generally low and made little impression upon the overall response, which tended to reinforce the religious question. The question was extended to the Coloured and Asian populations in 1936, although separate questionnaires were supplied.80 This enabled the survival of Hottentot and Bushman languages to be recorded (reduced to 3,828 speakers). The separate Asian schedules enabled the subsequent language shift in the Indian population to be monitored closely.81 Whereas in 1936 some 96.8 per cent of the Indian population recorded an Indian language as used in the home, by 1960 this had fallen to 82.4 per cent, with 14.4 per cent employing English.82 In 1946 everyone was asked a home language question, resulting in the emergence of a new range of data on indigenous Bantu languages.83 In 1960 the African language question was extended to languages spoken to ascertain proficiency in English, Afrikaans and a Bantu language.84 The link between language and ethnicity was, as yet, not made in the census.

Nationality and citizenship have been complex and contested areas of enquiry. The elements of ethnicity and place of birth have frequently been confused with the issue and terms used with different meanings at different times. The question on place of birth effectively acted as an approximation for nationality. This was because at Union, the inhabitants of the British Empire were subjects of the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, as were the majority of those recorded as born outside the Union.85 However, the country received immigrants on both a permanent and temporary basis. In 1911 immigrants were predominantly from the United Kingdom (Whites), India (Coloured), and Basutoland, Swaziland and Portuguese East Africa (African). Only the latter were not British by birth and were essentially migrant male mine workers. A table recorded the numbers of those who had become British subjects by naturalisation.86 This pattern continued for the Union period, although the flows of permanent immigrants were restricted, particularly in the case of Indians and Africans.87

Only in 1918 was a specific nationality question asked.88 It is not surprising that 97.6 per cent of the White population recorded themselves as British in 1918 and 98.4 per cent in 1921.89 The National Party-led government after 1924 sought to loosen the imperial ties. The debate leading to the enactment of the Nationality and Flag Act of 1927 led to divisions not only over the new flag, but the question of basic nationality. Thus at the time of the 1926 census, some 51.9 per cent of the White population indicated they were "British", while 46.2 per cent recorded they were "South African".90 In 1936 the percentage indicating itself as South African had increased to 97.8.91 The introduction of South African citizenship in 1949 therefore had little effect upon the formal identity of Whites in the census.92 The limitation of the question was appreciated in 1926 when a broad quest for parentage or origins was considered. As the Census Director wrote:

It was originally intended to go farther back to the grandparents to ascertain the national origin; but after considering all the aspects of the question it was decided to limit the question to the immediate parentage of the individual.93

It was realised that: "The answer will depend largely on the individual's point of view, which would be influenced by such circumstances as his upbringing, his home language, his religion, and probably even the environment in which he lives."94 National origin was a remarkably difficult concept to include in a census and no further enquiry was made for the White population.

The Asian population had been asked a question on "original nationality" rather than nationality in 1921, with 97.3 per cent identifying themselves as "Indian".95 In 1936 the question had been formal nationality, resulting in 81.6 per cent indicating Indian (South African) and only 16.7 per cent Indian (British) nationality.96 In 1946, the question reverted to origins as a means of exclusion from the South African fold, because "an Indian is classified as such irrespective of his birthplace, and irrespective of whether he is a citizen of India, Pakistan or South Africa".97 The nationality of the Coloured population presented few problems. In 1921 it was 99.8 per cent British and in 1936 as 99.7 per cent South African.98 The African population was not asked such a question, as it was stated that: "Owing to the difficulties in classification the Bureau does not tabulate statistics of the legal nationality, i.e. the actual citizenship of the non-white population".99 The African population was still excluded from the investigation in the 1960 census.100

Related to nationality was the question of the franchise, to which the census was most closely linked. Only the 1911 census included a table of voters.101 These distinguished between "White" and "Other than White" in the Cape of Good Hope. It might be noted that in that province, of the 148 500 voters, some 23 000 were "Other than White", with the "Whites" in a minority on the Tembuland constituency voters' role. The small number of Indian and Coloured voters in Natal was not distinguished. Later censuses offered no comprehensive tables of those qualified for the franchise. The disenfranchisement of the first the African (1936) and then the Coloured (1956) voters in the Cape of Good Hope was not reflected in the census.102

Other questions

The enquiry into identity is usually controversial, but other apparently simple and straightforward questions reveal a degree of complexity in the quest to describe the nation, particularly in view of the different questionnaires provided for the different groups. It may be assumed that less emotionally and ideologically charged questions have a greater degree of reliability.103 However, the framing and published outcomes of questions such as age and occupation reveal equally complex ramifications which impacted upon the view of the nation and its diversity. Other constant questions, including marital status and education, received contrasting degrees of attention, according to date and race. Occasional questions appearing in one or two censuses are more difficult to appraise, but did allow for the inference of trends over time.

The question on age revealed problems in an era before the general registration of births and deaths. Nevertheless, age was recorded in single years in the 1911 census, although only published on the basis of five-year cohorts.104 In 1921, as an economy measure, the African population was only reported on the basis of four broad groupings: infancy (under 1); youth (1-14 years of age); maturity (15-50) and old age (over 50).105 Criticism of this resulted in the appearance of five-year cohort figures again for the 1936 and subsequent censuses.106 Only in 1960 were single age groups listed for all race groups.107 The African statistics illustrated the continuing problems of recording ages, with large numbers giving 30, 40, 50 and 60 as their age, but comparatively few for the years on either side. Nevertheless, people often knew when they were born with relation to some significant historical event in the local community. In 1911 enumerators sought to establish people's ages by reference such events.108 The enumerators for the 1946 and 1951 censuses were supplied with suitable lists of important historical events to assist in their task.109 One of the outcomes of the age tables was the publication of "Life Tables" as actuarial information. Initially (1921), the tables covered only the Whites, but the Coloured population was added in 1936 and the Asian population in 1946.110 In 1951 it was still not possible to do so for the African population.111 The exercise was not attempted for the 1960 census.

The enquiry into occupation reveals a similar divergence in approach.112 In 1911 the modified British classification system, adopted by the Cape of Good Hope in 1875, was applied to the entire population.113 It should be noted that the classification system had already been superseded in Great Britain, and therefore comparability with the metropolis was lost.114 National occupational tables were produced in the 1911 census, although cross-tabulated by race. In 1921 the approach changed. The European, Coloured and Asian population were classified according to the new British 33-class classification system, while the African population was classified according to a special, simplified 18-occupation scheme.115 The latter included a category entitled "peasants" to which 50.7 per cent of African adults were assigned. In common with other dominions the British classification was subsequently abandoned in favour of a locally devised scheme.116 Thus in 1936, a new 10-class classification was applied to everyone, but no national statistics were compiled.117 This was repeated in 1946, with the significant change in the classification of African females engaged in agriculture from the economically active to the dependant category. As a result some 1.15 million adult women were removed from the economically active tables, thus substantially under rating the African contribution to the economy.118 In 1960 the International Standard Classification of Occupations, published in 1958, was adopted and adapted to South African conditions.119 Again individual tables were published for the four race groups, with minimal space devoted to national totals. It might be noted that the two major commissions of enquiry, undertaken in the 1950s which were to underpin the apartheid project in the rural areas, encountered significant gaps in the economic census material, which required substantial supplementation.120

In 1911 a question on marital status was included and was retained in a similar form throughout the Union period. A question on polygamy was asked of the entire population in 1911, resulting in the interesting observation that it was practised by few Cape Moslems, although their religion permitted the practice.121 Thereafter, only Coloureds, Asians and Africans were asked such a question.122 Additional issues of the fertility of the White population were included after the First World War as relative demographic decline was evident.123 In similar vein in 1926 a question of orphans was included, paralleling the British census enquiry in the post-war era.124

The education question had a far more varied history. In 1911 basic literacy, in any language, was sought for all people.125 In 1921, except for the African population, an enquiry into literacy in the two official languages was undertaken.126 The African population was still asked a question on basic literacy in any language. This pattern was continued for both 1946 and 1951, although Africans were questioned on literacy in English, Afrikaans and any Bantu language.127 Only in 1960 was an education question inserted, with a request for the standard level of education passed and qualifications held. In a reversal of previous trends the enquiry was applicable to all groups.128

Other questions only appeared in one or two censuses, but a similar picture emerges. Thus, in 1911 an agricultural census was conducted as an integral part of the population census.129 This followed colonial precedents, but was not repeated as subsequent enquiries into agriculture excluded the scheduled African rural areas.130 Other questions were of limited scope, such as that concerning the wages paid by Whites to their domestic servants in 1941.131 Finally, income statistics were only published in the 1960 census tables and the African population was once again excluded.132 It might be noted that Part X of the 1911 census, entitled "Supplementary Tables", had sought amongst other returns to tackle the issue of income, but with limited success. 133This volume covered a diverse range of institutional returns concerning education, religious denominations, industries, fisheries, mines and vehicles, which were not included with the population census again.

Conclusion

The census is one of the major elements in the observation and definition the population of the state in statistical terms. The creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910 required a new definition of the state and its population to supersede that presented by the earlier colonial and republican censuses for the different territories involved. Definition was initially constrained by the requirements of membership of the British Empire and the advice offered by the Colonial Office in London, which was generally accepted. However, with the development of political independence came independence in observation and the replacement of imperial concerns with local priorities, paralleling the experience of the other dominions of Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The functional separation of the dominion from the United Kingdom was a gradual process, with change taking place at virtually every enumeration, contributing to a significant lack of comparability between censuses by 1960-61. The last two censuses were integral to the apartheid project in terms of the statuary classification of the population and the presentation of the statistical basis of physical separation. The power spoken to by the census resided firmly in Pretoria by 1960 and no longer partially in London as it had in 1911.

The 1911 census continued in the British mould, following the detailed guidelines drawn up in London and with the presentation of the results appearing little different from the previous colonial censuses. It was an all-inclusive undertaking with a uniform enquiry into all members of the population regardless of race, which was but one of many personal attributes, albeit the most important. In contrast the 1918 "Whites only" census was a marked change with a close resemblance to the exclusivity of the South African Republic's only census in 1890. Nevertheless, some British African colonial censuses were no more ambitious. It was the 1921 enumeration which witnessed a significant dichotomy of approach, as an attempt was made to reconcile these two inheritances. On the one hand, continued adherence to British precedents was marked in such features as the adoption of the new British occupational classification, which was not useful in South African conditions. On the other hand, the institution of separate census questionnaire forms for the different race groups broke the ideal of inclusiveness and uniformity, which was not to be restored in subsequent enumerations. The concept of statistical collection as an integral part of the colonial project therefore becomes problematical in the South African context.

After 1911, statistical attention was primarily directed towards the White population. New questions were introduced into the questionnaire for Whites, according to changing official requirements for additional information. Sometimes such innovations were subsequently included in the schedules for the Coloured and Asian populations, but rarely in that for the African population. Even in 1960, with the abandonment of separate "Non-European" volumes and greater uniformity in questionnaire, the result is not greater integration, but segregation of the results into separate racially defined blocks of pages within the combined reports. In consequence the European population emerges in greater detail at the same time as the African and, to a lesser extent the Coloured and Asian populations recede in the resultant reports, compromising the utility of the data. The Union censuses thus increasingly defined the South African state and nation in racially exclusive terms. The integrative aspect of the census noted elsewhere is lacking as the fragmentation of population is symbolised by the fragmented nature of the published reports. Indeed the description of the population in the Union censuses is often essentially that of a White nation to the exclusion of other people, clearly undermining the link noted elsewhere between census taking and nation building. It is therefore doubtful whether the census authorities of the period adequately fulfilled their task and provided "the descriptions which speak to power with useful information".

This study has relied upon the published record of the Union censuses. Clearly there is far more to be said, particularly if sufficient surviving records are made accessible to public scrutiny. The scale of the census, the time constraints within which it had to operate, and the constant official pressure for rapid results, precluded much of the informative departmental commentary which accompanied the written record in the other dominions. Similarly the destruction of the original household questionnaires limits the opportunities for genealogical research. The census organisation produced authoritative statistics which were utilised by state departments and others with apparently limited comment and input into the form of the enumeration. There remains much to be investigated concerning the organisation and execution of the census, which has provided a wealth of statistics but requires the context to be explored more adequately.

Anthony Christopher is Professor Emeritus of Geography at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth. His research interests include an examination of the census records of the British Empire and Commonwealth. The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation towards the costs of this research is hereby acknowledged. The opinions expressed and the conclusions arrived at are those of the author and should not necessarily be attributed to the National Research Foundation.

1. J.C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1998), pp 11-83.

2. E. Higgs, "The Rise of the Information State: The Development of Central State Surveillance of the Citizen in England 1500-2000", Journal of Historical Sociology, 14, 2001, pp 175-197.

3. D.I. Kertzer and D. Arel, Census and Identity: The Politics of Race, Ethnicity and Languages in National Censuses (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002), pp 1-42.

4. S. Szreter, H. Sholkamy, and A. Dharmalingam, Categories and Contexts: Anthropological and Historical Studies in Critical Demography (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004), p 16.

5. W. Safran, "Names, Labels, and Identities: Sociopolitical Contexts and the Question of Ethnic Categorization", Identities, 15, 2008, pp 437-461.

6. M.J. Anderson, The American Census: A Social History (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1988); M.J. Anderson and S.E. Fienberg, Who Counts? The Politics of Census-taking in Contemporary America (Russell Sage, New York, 1999); M.G. Hannah, Governmentality and the Mastery of Territory in Nineteenth-Century America (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000); D.S. Hillygus, N.H. Nie, K. Prewitt and H. Pals, The Hard Count: The Political and Social Challenges of Census Mobilization (Russell Sage, New York, 2006); M. Nobles, Shades of Citizenship: Race and the Census in Modern Politics (Stanford University Press, Stanford, 2000); J. Perlmann and M. Waters, The New Race Question: How the Census Counts Multiracial Individuals (Russell Sage, New York, 2002); C.E. Rodriguez, Changing Race: Latinos, the Census and the History of Ethnicity in the United States (New York University Press, New York, 2000); K.M. Williams, Mark One or More: Civil Rights in Multiracial America (University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2006).

7. B. Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Verso, London, 1991), pp 163-185; E. Higgs, Life, Death and Statistics: Civil Registration, Censuses and the Work of the General Register Office 1836-1952 (University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, 2004), p vii.

8. G. Alleaume and P. Fargues, "La Naissance d'une Statistique d'État. Le Recensement de 1848 enÉgypte", Histoire et Mesure, 13, 1/2, 1998, pp 147-193; S.J. Shaw, "The Ottoman Census System and Population 1831-1914", International Journal of Middle East Studies, 9, 1978, pp 325-338.

9. F. Hirsch, "The Soviet Union as Work-in-Progress: Ethnographers and the Category 'Nationality' in the 1926, 1937 and 1939 Censuses", Slavic Review, 56, 1997, pp 251-278; E. Hirsch, Empire of Nations: Ethnographic Knowledge and the Making of the Soviet Union (Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 2005), p 14.

10. G. Aly and K.H. Roth, The Nazi Census: Identification and Control in the Third Reich (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2004), pp 56-93.

11. D. Arel, "Demography and Politics in the First post-Soviet Censuses: Mistrusted State, Contested Identities", Population-E, 57, 2002, pp 801-827; D. Arel, "Interpreting 'Nationality' and 'Language' in the 2001 Ukrainian Census", Post-Soviet Affairs, 18, 2002, pp 213-249; B. Dave, "Entitlement Through Numbers: Nationality and Language Categories in the First post-Soviet Census of Kazakhstan", Nations and Nationalism, 10, 2004, pp 439-459; G. Uehling, "The First Independent Ukrainian Census in Crimea: Myths, Miscoding and Missed Opportunities", Ethnic and Racial Studies, 27, 2004, pp 149-170.

12. A.J. Christopher, "The Quest for a Census of the British Empire c1840-1940", Journal of Historical Geography, 34, 2008, pp 268-285.

13. A. Appadurai, "Numbers in the Colonial Imagination", in C.A. Breckenridge and P. van der Veer (eds), Orientalism and the Postcolonial Predicament: Perspectives on South Asia (University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1993), pp 314-340.

14. B.S. Cohn, "The Census and Objectification in South Asia", in B.S. Cohn (ed.), An Anthropologist among the Historians and Other Essays (Oxford University Press, Delhi, 1981), pp 73-101.

15. K.W. Jones, "Religious Identity and the Indian Census", in N.G. Barrier (ed.), The Census in British India: New Perspectives (Manohar, New Delhi, 1981), p 75.

16. Barrier, The Census in British India; S. Maheshwari, The Census Administration under the Raj and after (Concept, New Delhi, 1996); S.P. Mohanty and A.R. Momin, Census as Social Document (Rawat, Jaipur, 1996); S.C. Srivastava, Indian Census in Perspective (Office of the Registrar General, New Delhi, 1972).

17. Colonial Social Science Research Council, Demography and the Census in the Colonies (Colonial Office, London, 1946), p 5.

18. R.R. Kuczynski, Demographic Survey of the British Colonial Empire, Volume I, West Africa (Oxford University Press, London, 1948); R.R. Kuczynski, Demographic Survey of the British Colonial Empire, Volume II, East Africa (Oxford University Press, London, 1949).

19. R.R. Kuczynski, Demographic Survey of the British Colonial Empire, Volume III, West Indian and American Territories (Oxford University Press, London, 1953).

20. B. Curtis, The Politics of Population: State Formation, Statistics and the Census of Canada, 1840-1875 (University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2001), pp 192-194.

21. L.G. Hopkins, The Australian Population Census (Library of Parliament, Canberra, 1983), p 3.

22. New Zealand, Population Census 1951, Volume 8 Report (Department of Census and Statistics, Wellington, 1956), p 1.

23. G20-'66, Census of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope 1865 (Government Printer, Cape Town, 1866); G42-'76, Census of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope 1875, Part I Summaries (Government Printer, Cape Town, 1877); G6-'92, Census of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope 1891 (Government Printer, Cape Town, 1892).

24. Verslag van den Census, 1890 (C. Borckenhagen, Bloemfontein, 1890).

25. Verslag van de Volkstelling, 1890 (Staatsdrukker, Pretoria, 1891).

26. Race classification has dominated census taking. In this paper contemporary usages have been adopted, where appropriate, and elsewhere the present post-apartheid, four-fold nomenclature of African, Coloured, Indian and White.

27. Census of the Colony of Natal 1891 (Government Printer, Pietermaritzburg, 1891).

28. G19-1905, Census of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope 1904 (Government Printer, Cape Town, 1905); Census of the Colony of Natal 1904 (Government Printer, Pietermaritzburg, 1905); Census Report of the Orange River Colony 1904 (Government Printer, Bloemfontein, 1905); Census of the Transvaal Colony and Swaziland 1904 (Waterlow, London, 1906).

29. Australia, Census of the Commonwealth of Australia 1911 (Government Printer, Melbourne, 1914), p 62.

30. UG32-1912, Census of the Union of South Africa 1911, Report (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1913), p iii.

31. Cd2660, Report on the Census of the British Empire 1901 (HMSO, London, 1906), pp lix-lxiii.

32. UG32-1912, Census 1911, Report, p v.

33. UG15-1913, Report of the Second Delimitation Commission (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1913), p 5.

34. UG58-'19, Report of the Third Delimitation Commission (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1919), p 6.

35. J.-P. Beaud and J.-G. Prévost, "Statistics as the Science of Government: The Stillborn British Empire Statistical Bureau, 1918-20", Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 33, 2005, pp 369-391.

36. UG37-'24, Report on the Third Census of the Union of South Africa 1921 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1924), Appendix B.

37. UG4-'31, Fourth Census of the Union of South Africa 1926, Part XIII Summaries and Analysis (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1931), p 1.

38. UG21-'28, Report of the Fifth Delimitation Commission (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1928), p 1.

39. UG11-1933, Report with Summaries and Analysis of the Fifth Census of the Union of South Africa 1931 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1933), p ix.

40. UG21-'38, Sixth Census of the Union of South Africa 1936, Volume I Geographical Distribution (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1938), p vii.

41. "Report of the Eighth Delimitation Commission", Government Gazette No 3139 (8 January 1943) (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1938), p iv.

42. UG51-1949, Population Census 1946, Volume I Geographical Distribution (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1949), p iii.

43. UG-'42-'55, Population Census 1951, Volume I Geographical Distribution (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1955), p v.

44. RP62/1963, Population Census 1960, Volume I Geographical Distribution (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1963), p i. Subsequent census reports were no longer formally presented to parliament and therefore did not receive RP numbers.

45. National Archives Depot, Pretoria, (hereafter NAD), Record Series STK consisted exclusively of the enumerators' summary books for the 1911-1946 censuses. They were withdrawn from public consultation in 1990 for reasons of confidentiality, which preclude access to other related unpublished material.

46. C. Hakim, "Census Reports as Documentary Evidence: The Census Commentaries 1801-1951", Sociological Review, 28, 1980, pp 551-580.

47. UG24-'42, Sixth Census of the Union of South Africa 1936, Volume V Birthplaces, Period of Residence and Nationality (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1942), p vi.

48. UG37-'24, Report, Third Census, 1921.

49. Population Census 1960, Sample Tabulation Volumes 1-8 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1962-65).

50. Population Census 1960, Volumes 1-11 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1963-70).

51. Report No. 02-02-01, Urban and Rural Population of South Africa 1904 to 1960 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1968).

52. S. Dubow, Scientific Racism in Modern South Africa (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995), pp 1-19. The problems of the census classification are not specifically mentioned.

53. A.K. Khalfani and T. Zuberi, "Racial Classification and the Modern Census in South Africa, 1911-1996", Race and Society, 4, 2001, pp 161-176.

54. Cd 2660, Census of the British Empire 1901, p xlvii.

55. N. Stepan, The Idea of Race in Science: Great Britain 1800-1960 (Palgrave Macmillan: London, 1982) p 111.

56. A.J. Christopher, "Race and the Census in the Commonwealth", Population, Space and Place, 11, 2005, pp 103-118.

57. G42-'76, Census, Cape of Good Hope 1875, p 3.

58. G19-1905, Census, Cape of Good Hope 1904, p xxi.

59. G6-'92, Census, Cape of Good Hope 1891, p xix.

60. UG32-1912, Census 1911, Report, p v.

61. UG37-'24, Report, Third Census 1921, p 26.

62. The National Archives, Kew, RG19/56 General Register Office correspondence, Cousins (Director of Census and Statistics, Pretoria) to Vivian (Registrar General of England and Wales) 16 September 1921.

63. UG42-'55, Population Census 1951, Volume I, p 2.

64. I. Makeba Laversuch, Census and Consensus? A Historical Examination of the US Census Racial Terminology Used for American Residents of African Ancestry (Peter Lang, Frankfurt, 2005), p 1.

65. NAD, File STK012-13, Beaufort West 1911, Census enumerators' summary books, areas 1-5.

66. UG21-'38, Sixth Census 1936, Volume I, p ix.

67. UG12/42, Sixth Census of the Union of South Africa 1936, Volume IX Natives (Bantu) and Other Non-European Races (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1942), p xxv.

68. M. Yap and D.L. Man, Colour, Confusion and Concessions: The History of the Chinese in South Africa (University of Hong Kong Press, Hong Kong, 1996), pp 433-435.

69. UG42-'55, Population Census 1951, Volume I, p v.

70. A. Suzman, "Race Classification and Definition in the Legislation of the Union of South Africa 1910-1960", Acta Juridica, 1960, pp 339-367.

71. E.M. Crawford, Counting the People: A Survey of the Irish Censuses 1813-1911 (Four Courts, Dublin, 2003), p 25.

72. Cd2660, Census of the British Empire 1901, pp xlix-li.

73. M. Suzman, Ethnic Nationalism and State Power: The Rise of Irish Nationalism, Afrikaner Nationalism and Zionism (Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 1999), p 5.

74. UG12e-1912, Census of the Union of South Africa 1911, Part VI Religion (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1913), pp 924-925.

75. UG12/42, Sixth Census 1936, Volume IX, pp 63-67; Population Census 1960, Volume 3 Religion (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1966), p 131.

76. H. Pretorius and L. Jafta, '"A branch springs out': African Initiated Churches", in R. Davenport and R. Elphick (eds), Christianity in South Africa: A Political, Social and Cultural History (University of California Press, London, 1998), pp 211-226.

77. J. Kralt, "Ethnic Origins in the Canadian Census 1871-1986", in S.S. Halli, F. Trovato and L. Driedger (eds), Ethnic Demography: Canadian Immigrant, Racial and Cultural Variations (Carleton University Press, Ottawa, 1990), pp 13-29.

78. UG1-'21, Census of the European or White Races of the Union of South Africa 1918, Part III Education (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1920), p 46.

79. UG44-'38, Sixth Census of the Union of South Africa 1936, Volume VI Languages (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1938), pp 1-10.

80. UG44-'38, Sixth Census 1936, Volume VI, p xi.

81. R. Mesthrie, "Language Change, Survival, Decline: Indian Languages in South Africa", in R. Mesthrie (ed.), Language in South Africa (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002), pp 161-178.

82. Population Census 1960, Volume 7(1) Characteristics of the Population: Age, Marital Status and Home Language (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1968), p 366.

83. UG18/1954, Population Census 1946, Volume IV Languages and Literacy (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1954), pp 148-155.

84. Population Census 1960, Volume 7(1), p 502.

85. UG32-1912, Census 1911, Report, pp lvii-lxv.

86. UG32f-1912, Census of the Union of South Africa 1911, Part VII Birthplaces (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1913), p 1048.

87. Census of Population 1960, Volume 9 Miscellaneous Characteristics (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1968), pp 142-139.

88. UG1-1920, Census of the European or White Races of the Union of South Africa 1918, Part III Education (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1920), p 46.

89. UG35-'23, Third Census of the Union of South Africa 1921, Part III Official Languages Spoken (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1923), p iii.

90. UG35-'29, Fourth Census of the Union of South Africa 1926, Part VI Nationality and Parentage (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1929), p iii.

91. UG24-'42, Sixth Census of the Union of South Africa 1936, Volume V Birthplaces, Period of Residence and Nationality (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1942), p xvi.

92. UG34-'54, Population Census 1951, Volume IV Birthplace, Year of Arrival and Nationality (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1954), p 43. The report covered Whites in 1951 and all races in 1946.

93. UG35-'29, Fourth Census 1926, Part VI, p iii.

94. UG35-'29, Fourth Census 1926, Part VI, p iii.

95. UG37-'24, Report, Fourth Census 1921, p 240.

96. UG24-'42, Sixth Census 1936, Volume V, p xxi.

97. UG34-'54, Population Census 1951, Volume IV, p vi.

98. UG37-'24, Third Census 1921, Report, p 239; UG24-'42, Sixth Census 1936, Volume V, p 146.

99. UG38-'59, Population Census 1951, Volume VII Marital Status, Religion, Birthplaces of Coloureds, Asiatics and Natives (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1959), p viii.

100. Population Census 1960, Volume 11, Part 1 White Families, Part 2 Coloured and Asian Families (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1970).

101. UG32-1912, Census 1911, Report, p 19.

102. I. Loveland, By Due Process of Law: Racial Discrimination and the Right to Vote in South Africa 1855- 1960 (Hart, Oxford, 1999), pp 179 -202, 336 -362.

103. T.L. Alborn, "Age and Empire in the Indian Census 1871 -1931", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 30, 1999, pp 61 -89.

104. UG32a-1913, Census of the Union of South Africa 1911, Part II Ages of the People (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1913).

105. UG40-'24, Third Census of the Union of South Africa 1921, Part VIII Non-Europeans (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1924), 46 -50.

106. UG50-'38, Sixth Census of the Union of South Africa 1936, Supplement to Volume IX Ages and Marital Condition of Bantu Population (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1938), p v.

107. Population Census 1960, Volume 9 Miscellaneous Characteristics, pp 1 -2.

108. UG32-1912, Census 1911, Report, p xxxvii.

109. Census 1946, List of Important Historical Events and also of Zulu Royal Regiments for the guidance of enumerators estimating the ages of Natives (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1945). A revised version was issued in 1950 to guide enumerators in the 1951 census.

110. UG14/1951, Population Census 1946, Volume III South African Life Tables (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1951).

111. UG49/1960, Population Census 1951, Volume VIII South African Life Tables (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1960).

112. A.J. Christopher, "Occupational Classification in the South African Census before ISCO -58", Economic History Review, 63, 2010, pp 891 -914.

113. UG32d-1912, Census of the Population of the Union of South Africa 1911, Part V Occupations (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1913), pp 441 -501.

114. E. Higgs, "The Struggle for the Occupational Census 1841 -1911", in R. MacLeod (ed.), Government and Expertise: Specialists, Administrators and Professionals 1860-1919 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1988), pp 73 -86.

115. UG37-'25, Third Census of the Union of South Africa 1921, Part VI Occupations and Industries (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1925), pp 2 -23; and UG40-'24, Third Census 1921, Part VIII, p 143.

116. E. Olssen and M. Hickey, Class and Occupation: The New Zealand Reality (Otago University Press, Dunedin, 2005), pp 29 -55.

117. UG11-'42, Sixth Census of the Union of South Africa 1936, Volume VII Occupations and Industries (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1942), pp v -xxxii; and UG12/42, Sixth Census 1936, Volume IX, pp xv -xviii.

118. UG41/1954, Population Census 1946, Volume V Occupations and Industries (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1954), p v.

119. Population Census 1960, Volume 8 Part 1 Occupation (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1969), p ix.

120. UG61-1955, Summary of the Report of the Commission for the Socio-Economic Development of the Bantu areas of the Union of South Africa (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1955), pp 53 -55; Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the European Occupancy of the Rural Areas (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1960), pp 9-11. The latter report was unnumbered.

121. UG32c-1912, Census of the Union of South Africa 1911, Part IV Conjugal Conditions (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1913), p xlvi.

122. UG32-'23, Third Census of the Union of South Africa 1921, Part IV Marital Status (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1923), p iii; UG40-'24, Census 1921, Part VIII, p 102.

123. UG42-'29, Fourth Census of the Union of South Africa 1926, Part X Fertility of Marriage (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1929).

124. UG36-'29, Fourth Census of the Union of South Africa 1926, Part V Orphanhood (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1929).

125. UG32b-1912, Census of the Union of South Africa 1911, Part III Education (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1913).

126. UG37-'24, Third Census 1921, Report, Questionnaires in Appendix B.

127. UG18/1954 Population Census 1946, Volume IV; UG64/1958 Population Census 1951, Volume VI Languages and Literacy (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1958).

128. Population Census 1960, Volume 4 Education (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1967).

129. UG32h-1912, Census of the Union of South Africa 1911, Part IX Livestock and Agriculture (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1913).

130. UG53-1919, Agricultural Census 1918 (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1919).

131. UG46-1946, Population Census 1946, Wages of Domestic Servants (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1946).

132. Population Census 1960, Volume 5 Personal Income (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1967). Some previously unpublished figures from the 1951 census were included, pp A1 (Whites), B1 (Coloureds), C1 (Asians).

133. UG32i-1912, Census of the Union of South Africa 1911, Part X Supplementary Tables (Government Printer, 1913), p 1416.