Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Historia

On-line version ISSN 2309-8392

Print version ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.55 n.2 Durban Nov. 2010

"Fools rush in": writing a history of the concentration camps of the South African War

"Fools rush in": die skryf van 'n geskiedenis van die konsentrasiekampe van die Suid-Afrikaanse Ooorlog

Elizabeth van Heyningen

ABSTRACT

In the light of recent controversy over the hygiene of the Boers in the camps of the South African War, this article explores some of the difficulties in writing a history of the camps. The article argues that although the British Blue Books were politically tainted, this does not necessarily invalidate the contents. Although the authors were loyal to the British cause and shared a Victorian middle class culture, which led them to view Boer hygiene critically, they were so consistent in their comments that they cannot be disregarded. An analysis of the camp registers confirms a picture of great poverty amongst the rural population who formed the bulk of the camp inmates. The war contributed to the destruction of republican society, creating the poor white crisis which troubled Afrikaners so greatly in the twentieth century. The post-war emergence of Afrikaner nationalism was concerned not only with unifying Afrikaners politically and uplifting them economically, but with gentrifying these urbanising poor whites. This process has been little discussed but it has bitten deeply into Afrikaner consciousness and explains the reluctance, even of twenty-first-century Afrikaners, to recognise that this pre-industrial rural society possessed a different culture.

Keywords: South African War; Anglo-Boer War; concentration camps; poor whites; middle class culture; sanitation; hygiene; British Blue Books; Ladies Commission.

OPSOMMING

In die lig van die onlangse omstredenheid oor die higiëne van die Boere in die kampe van die Suid-Afrikaanse Oorlog, ondersoek hierdie artikel sommige van die probleme wat uit die skryf van 'n geskiedenis van die kampe spruit. Hierdie artikel voer aan dat alhoewel die Britse Blouboeke polities gekleurd was, dit nie sonder meer die inhoud daarvan ongeldig maak nie. Alhoewel die skrywers lojaal aan die Britse saak was en 'n Victoriaanse kultuur gedeel het wat hulle krities teenoor Boer higiëne gelaat het, was hul kommentaar so konsekwent dat dit nie verontagsaam kan word nie. 'n Ontleding van die kampregisters bevestig 'n beeld van enorme armoede onder die landelike bevolking wat die grootste groep van kampbewoners uitgemaak het. Die oorlog het bygedra tot die vernietiging van die republikeinse gemeenskap en in die proses die armblankekrisis geskep wat die Afrikaners in die twintigste eeu soveel probleme verskaf het. Die naoorlogse opkoms van Afrikanernasionalisme was nie net bemoeid met die politiese vereniging van die Afrikaners en hul ekonomiese opheffing nie, maar ook met die verburgering van die verstedelike armblankes. Weinig aandag is aan hierdie proses gegee, maar dit het diep inslag gevind in die Afrikaner se psige en verduidelik die onwilligheid, selfs van Afrikaners in die een-en-twintigste eeu, om te erken dat hierdie voor-industriële landelike samelewing oor 'n ander kultuur beskik het.

Sleutelwoorde: Suid-Afrikaanse Oorlog; Anglo-Boeroorlog; konsentrasie kampe; armblankes; middelklas culture; sanitasie; Britse Blouboeke; Vroue Kommissie.

A recent article in the South African Journal of Science (SAJS) has created a certain amount of anger in Afrikaner circles after Rapport newspaper published a piece on it.1 This was followed by a discussion by Professor Fransjohan Pretorius, in a critique entitled "Toiletpraatjies Stink".2 His comments bring to the fore some of the very real problems in writing a history of the camps.

When I came to work on the history of the camps, I was struck by the dearth of critical questioning of the existing literature which was, in any case, sparse despite an apparent plethora of camp testimonies.3 The notion that the story has been told is a deeply held conviction; one of the referees of the SAJS article remarked on the difficulty of saying anything fresh about the camps in the light of the voluminous literature that exists. But it seemed to me that there were a host of unanswered questions and a considerable archive which had never been examined systematically. I tried to respond to the most immediate question, why there has been so little research on the camps, in an article published in the Journal of Southern African Studies (JSAS).4 I argued there that the "haze" of memorials, women's testimonies and poetry, amongst other forms of memorialisation, have convinced people that there is little more to be told. More recent forms of commemoration, like the Scorched Earth video, occasionally still aired on DSTV, and the magnificent photographic record, Suffering of War, have helped to reinforce this impression.5

The press debates have raised a related issue that is clearly still very alive. One angry correspondent wrote to me, "The so[-]called barbaric Boers ... [are] descendents of mostly high class Protestant[s], very skilled families, having enough money and influence to buy their way out of Catholic persecuted Europe. Obviously they know about sanitation."6 For him Afrikaners are civilised Europeans, not dirty African peasants. His remarks demonstrate the continuing power of mythmaking amongst ordinary Afrikaners, but it is also reinforced by Professor Pretorius's argument that the majority of the camp inmates were middle class, and his rejection of the evidence of the Blue Books that the camp people were insanitary. Why is the belief still so powerful that the camp inmates were predominantly prosperous, educated and middle class, rather than an impoverished pre-industrial rural peasantry practising a lifestyle that was widespread before the era of public health reforms?

Reading the Blue Books

One approach is to look more carefully at the evidence of the British Blue Books. They are key documents that were published by the War Office from November 1901, partly in response to Emily Hobhouse's revelations in June 1901 which had led to questions in the House of Commons about camp mortality. For decades they have been the primary British source to be consulted. Of these, the most important is Cd 819, together with Cd 893, the report of the Ladies Committee.7 Blue Books have to be treated with caution. They are parliamentary papers published by the government of the day to explain and defend their actions; in other words, they are highly politicised - never more so than in wartime when dealing with controversial matters. The camp Blue Books can be regarded as a profoundly cynical exercise on the part of the War Office.

With regard to Cd 893, and contrary to the optimistic interpretation of scholars like Paula Krebs, Elaine Harrison argues that the appointment of the Ladies Committee was designed to deflect attention from the incompetence of the camp administration. The fact that it was not a Royal Commission, whose findings would be reported to parliament, and that it consisted only of women, signalled to the military high command in South Africa that the matter was of little importance.8 For St John Brodrick, Secretary of State for War, this was not an investigation but an inspection, concerned primarily with charitable relief.9 To Joseph Chamberlain, Secretary of State for the Colonies, the Blue Books partly exonerated the British of the camp deaths by blaming the Boers themselves, highlighting their insanitary lifestyle and their deficiencies in childcare.

The politicised context of the Blue Books has also deflected others from taking their content seriously. From Emily Hobhouse onwards, pro-Boers and Afrikaners have been reluctant to concede that the indictment of the Boers had any validity. Understandably they have been angered by the tone of these documents, which are patronising at best, and often contemptuous of the Boer way of life. However, it is one thing to recognise the politicised nature of the Blue Books. It is another to argue that the context invalidated the contents. How reliable were they? The British did not censor the reports, which were published almost intact.10 Although material was selected for publication, the contents were not tampered with.

What of the people who wrote the reports? One of the most prominent was Dr Kendal Franks, who was seconded from the British army to report on the camps. He clearly embraced the political and cultural mission of the British in South Africa. Many of the most explicit descriptions of Boer vernacular medicine came from his pen and he was one of the earliest to condemn Boer sanitation and childcare. In one of his first reports, on the Irene camp, he emphasised the combination of poverty, dirt and ignorance. His conclusion encapsulates all the most striking prejudices against the Boers:

The high death rate among the children, I would like to emphasise again, is in no way due to want of care or dereliction of duty on the part of those responsible for this camp. It is, in my opinion, due to the people themselves; to their dirty habits both as regards their own personal cleanliness and the cleanliness of their children and their surroundings; to their prejudices; their ignorance; and their distrust of others, even their own nationality, when their advice runs counter to their own preconceived and antiquated ideas. This is specially noted in connection with their treatment of the sick, to their rooted objection to soap and water, and to hospitals.11

How is one to interpret such a statement? Was Franks lying to please his political masters? Was he ignoring the conditions which made it so difficult to maintain cleanliness? Was he generalising from one or two instances? Or does one have to give some credence to his comments? These questions go to the heart of the controversy.

Dublin-born Sir Kendal Matthew St John Franks was a member of a well-known Irish family and had a distinguished medical career, pioneering the use of antiseptic and aseptic surgery in Ireland. He moved to South Africa in 1896 because of his wife's health, settling in Johannesburg the following year. When war broke out he was attached to Lord Roberts' staff as one of five consulting surgeons to the British forces and was present at a number of major engagements. He was mentioned in dispatches and was requested by Lord Kitchener to inspect the camps. He remained in South Africa for the rest of his life, continuing to have an outstanding medical career.12 He was, then, a successful medical man rather than a politician, who had given up a brilliant career in Britain to make his life in South Africa for the sake of his wife. His reports tended to be full and precise, even pedantic.

Franks' remarks were undoubtedly coloured by his political loyalties. The Irene report was partly a response to the criticisms which had been made by the young Boer volunteer nurse, Johanna van Warmelo.13Franks considered that her section of the camp, which took in the latest arrivals, was the worst part, overcrowded, the people poverty-stricken and poorly clad. "In all these tents poverty, dirt, and ignorance reign supreme", he wrote. Elsewhere he was "struck by the contented, cheery, well-cared-for appearance of the people".14He considered that the rations were, on the whole, adequate and of good quality. The water supply was excellent and so were the sanitary arrangements, so there had been little typhoid. The tone of the report was positive, even optimistic and Franks' recommendations were limited - more hospital tents and more nurses; more blankets and warm clothing; more milk for the children, and more coffee for adult men. The only real problem, Franks implied, was the measles epidemic and Dr Neethling (a Boer doctor, Franks noted) attributed the high mortality to the ignorance and poor nursing of the mothers.

Most of the criticisms of Boer hygiene came from the camp medical officers. I have argued elsewhere that they shared a common medical culture which was the product of the public health revolution that had reduced mortality so significantly in Britain's industrial cities in the nineteenth century.15 Most were young men, recently qualified, driven abroad by Britain's overcrowded medical market and seeking to make careers for themselves in South Africa. If anything, they tended to be overzealous, sometimes leading to clashes with their superintendents.16 Nevertheless, there were several Boer doctors amongst them, including Dr Voortman in Bethulie and Aliwal North camps, and Drs van der Wall and Schnehage, both of whom came originally from Winburg. While these men may have had greater sympathy for the Boers, they usually had British qualifications and there is nothing in the records to suggest that they thought very differently from their British colleagues on the matter of hygiene.

The members of the Ladies Committee also had much in common with one another. Millicent Garrett Fawcett, who chaired the committee, had worked actively for women's rights and was one of the founders of Newnham College, Cambridge. Married to the blind Liberal parliamentarian, Henry Fawcett, she had acted as his secretary and was intimate with British politics.17Lucy Deane, the daughter of Colonel Bonar Deane who had died at Laing's Nek in 1881, had qualifications from the National Health Society and, at the time of the war, was a Home Office sanitary inspector. She remained active in women's welfare throughout her life.18Alice, Lady Knox, was the least qualified for the job and she seems to have been included only to make up the numbers. A member of the landed gentry, she was the wife of General Knox. She had nursed in Ladysmith during the siege and was familiar with some of the camps, including Kroonstad.

The two doctors, Jane Waterston and the Hon Ella Scarlett, were both the products of a society that did its best to prevent women from gaining medical qualifications. Jane Waterston had come to South Africa originally as a Free Church of Scotland missionary but, after qualifying in medicine, had established a practice in Cape Town. Her life was devoted to the care of the poor, especially Africans, and she spoke Xhosa. Much of her well-known dislike of the Boers may have stemmed from her feeling for black people.19Hobhouse's accusation that the Ladies Committee failed to investigate the black camps is tendentious; this was not part of their limited brief and Deane's letters make it clear that Waterston, at least, visited them when she could.20Ella Scarlett was the daughter of the Irish aristocrat, Lord Abinger. She had an exotic career, first working at the court of the Emperor of Korea. After the South African War she went to Alberta, Canada and then to Oregon in the United States. During the First World War she served in Serbia, returning subsequently to the US. She ended her life as a member of the expatriate British community in Florence.21The third medical member of the team was Katherine Brereton. Like Lucy Deane, the daughter of a military officer, she was a "lady" nurse from a landed Norfolk family, who had worked at Guy's Hospital and at Birkenhead Children's Hospital before the war. In 1900 she had joined the nursing section of the Royal Army Medical Corps and had nursed in the Imperial Yeomanry Hospital in Deelfontein.22

These were all middle and upper class women and several of them were acquainted before the Ladies Committee was appointed.23Most were active in the cause of women's political and social emancipation and had achieved much in a world that did little to encourage women's education and independence. These were courageous, determined, highly intelligent and principled women. They have received a bad press because of their undoubted commitment to the British cause and because Emily Hobhouse cast doubt on their disinterestedness. But Hobhouse was a disappointed woman, for her claims to be a member of the committee had been disregarded despite her obvious qualifications. The first pages of the report, the "jam and blarney" as Deane called them, were unctuous.24But these were experienced, serious-minded women with a job to do, who were not easily put off by the hostility of male officials, and there is every indication that they did their best to fulfil their task.

Criticisms of Boer standards of hygiene came, then, from members of the Victorian middle classes, many of them intelligent and well educated, who shared a belief in the British colonial mission.25This mission was not simply a matter of conquest and Anglicisation, but embraced a complex set of ideas. As Ann Laura Stoler and Frederick Cooper have pointed out, the colonies were often "laboratories of modernity", where colonial officials could conduct experiments in social engineering without confronting the kind of popular resistance that they might find at home. For progressive colonial administrators, the measures of man were "rationality, technology, progress, and reason".26Debates at home about sexual standards, moral instruction, medical care and child rearing were transported to the colonies where they were worked out and clarified, in a dialogue between the metropolitan and the colonies.27These notions included gendered views on the appropriate roles of men and women, where men were the providers and protectors, and women the tender, caring but passive mothers. Civilisation as defined by the British, Catherine Hall observes, required a particular gender order, and it was part of the work of empire to teach it.28Many of these ideas were implemented in the camps where the British attempted to impose, not only a public health regime, but a new domesticity. Although the teachers and nurses in the camps did not entirely fulfil this ideal, for they were "new women", carving careers for themselves, the male camp officials also expected them to act as models of femininity. It was in this sense that the Transvaal director of burgher camps wrote that the nurses

have created a very favourable impression, being physically strong and attractive, and presenting by ocular demonstration, to the inmates of the Camps, examples of British womanhood. The moral effect of the association of these earnest noble-minded and cultivated ladies, with the people of the veld ... cannot fail to be productive of much good in many ways ...29

Through the writings of men like Thomas Carlyle and Charles Kingsley, lay Victorians as well as medical professionals had embraced the new sanitary principles. Public health reform was not confined to clean water and toilet practices. Sanitation, the Victorians believed, improved not only health but moral habits as well.30Combined with cleanliness and domesticity was the notion of respectability which, in turn, was closely associated with wealth. The respectable person was one who dressed decently and could mix on equal terms with anyone. To be respectable was to be a gentleman. Along with this striving for respectability was a changed attitude to poverty, which was now a source of shame.31Victorian culture, then, coloured the perspectives of camp officials. Nevertheless, the consistency of their observations needs some explanation beyond that of cultural difference and class prejudice.

One question demanding an answer is why so many officials tended to minimise the scale of the problems in the camps. Franks was not alone in glossing over the deficiencies. The upbeat tone was a common feature of camp reports, from General Maxwell down and sometimes in the face of mounting mortality and every indication of major failures in the camp system. It is one reason why the camp reports seem so questionable, for the apparent callousness almost certainly delayed action over the mortality.

One explanation seems obvious. The camp officials were reluctant to draw attention to their own shortcomings. These were men with careers to consider and they were understandably, if culpably, unwilling to rock the boat.32Added to this was the fact that in wartime, loyal officials do not indict their country's policies, however much they might disagree with them in private. Part of the hostility to the pro-Boers arose from the anger evoked by their "disloyalty" in criticising war policies.33Milner and the Ladies Committee knew that the camps policy had been a disaster. Lucy Deane expressed herself in terms that were not unlike those of Emily Hobhouse:

We all feel that the policy of the "Camps" was a huge mistake which no one but these unpractical ignorant Army men could have committed. It has made the people hate us, it is thoroughly unnatural and we were not able to cope with the hugeness of the task, at any rate the muddling old War Office wasn't; I believe it has lengthened instead of shortened the war . . . even those of us who approved at first are now of another opinion on the policy of them.34

But they could not say so publicly and even Milner had little influence over Kitchener's decisions.35 All they could do was to put the best face on things. For the victims, however, such a face was duplicitous.

There was another, less obvious, reason why camp reports tended to be so bland.36The great concern of the camp administration was typhoid, which had taken such a terrible toll of the British forces in Bloemfontein.37By 1900, typhoid was relatively well understood. The pathogen, Salmonella typhi, had been identified and it was known to be a disease of sanitation.38An effective vaccine was being developed although it was little used in the South African War. The treatment of the day, primarily a restricted diet and careful nursing, has stood the test of time.39 Doctors knew very well that the disease could be kept at bay through good sanitation but they feared that the disease was endemic in South Africa, especially in summer. Only constant vigilance prevented an epidemic but it was a malady that could be managed. In their eyes a successful camp was one in which typhoid was controlled.

Measles was another matter altogether. It was caused by a virus, so its origins were unknown at the time. It was a highly infectious and complex pathogen, which tended to reduce in virulence in large populations where it became endemic.40 In societies which lacked a substantial pool of immune hosts, it could become much more dangerous, its victims dying less of measles itself, than of subsequent respiratory or intestinal problems. Overcrowding and poor nutrition also increased itsintensity. There was no therapy and the only means of preventing a serious epidemic was isolation, virtually impossible in these wartime conditions. British doctors were familiar with measles as a common but relatively trivial childhood disease and they were overwhelmed by the epidemic that raged through the camps. The reports are replete with attempts to explain why it was so severe, ranging from those that pointed to the poor accommodation and nutrition to those, like that of Dr Neethling, that blamed the mothers. The doctors tended to regard the epidemic as an act of God, quite separate from the general health of the camp. It is for this reason, perhaps, why, in the midst of a major crisis, doctors could describe their camps as otherwise healthy.

These explanations do not face the issue of Boer hygiene, for it is on this point that most anger is aroused. How valid were they? Some doctors, like Franks and Dr Woodroffe of Irene camp, were particularly vocal but they were not the only men to remark on the difficulties in persuading the Boers to adopt cleanly habits. Over and over again, in report after report, in casual asides and even, occasionally, in comments from the Boer side, camp officials and others have commented on the insanitary practices of the country people.41

Of course it was extraordinarily difficult to maintain a clean family under camp conditions, especially in the first months when water and soap were in short supply and latrines were rudimentary. As I noted in the SAJS article:

On dark nights, when the entire family was sometimes struck down with dysentery or diarrhoea, it was impossible to expect them walk up to half a mile (.8 kilometres), to the latrines. The latrines themselves ranged from the trenches which the army used, and which were entirely unsuitable for small children, to the bucket system. Lack of wood, galvanised iron pails, transport animals, labourers ... all contributed to the difficulty of keeping the camps clean in the early months.42

But the criticisms go beyond toilet habits; it was a way of life that was being indicted. Dr G.B. Woodroffe of Irene camp observed that:

In the tents of some, slops and stools are allowed to remain for hours without being removed, blankets and shawls are often used as diapers for babies, with the result that the stench is unbearable. Many of the better class won't go near, much less into tents, of the dirtier, not to say poorer class.43

One reason why the authorities insisted that tent flaps be lifted daily, why the tents were struck periodically and why entire camps were sometimes moved, was because the ground became fouled, as Dr Richard Hamilton of Volksrust camp explained:

I have also noticed that there is less sickness in tents pitched on new ground. Illness is more prevalent in the older portion of the camp; this I believe to be due, in many cases, to the filthy habits of many of the burghers, and to the number of children. After a few weeks, the ground on which the tent is pitched becomes soaked with urine, slops, sputum, etc., and, if it were possible, I would advocate the removal of a section of the camp every month.44

Lack of sanitation was not confined to the camps. The Boer laagers, when they remained stationery for any length of time, were filthy. A number of commentators remarked on the insanitary state of the laagers besieging Mafeking. Flies were a major problem because the offal of slaughtered animals was never cleared away. The interiors of the wagons and tents were black with the "little devils" and flies flew into the mouths of the burghers as they struggled to eat. The stench from the latrines, built too close to the laager, was unbearable, the Rev Abraham Stafleu complained.45Paardeberg and Modderspruit, too, were gripped by disease and foreign doctors attached to the Boer forces, particularly, were critical of the lack of hygiene in the Boer laagers.46

Lack of sanitation was certainly not unique to the Boer republics. The camps have been seen too much in isolation, as sui generis, a unique experience. In the Cape Colony, as public health reforms were introduced by modernising doctors from the 1880s, and district surgeons' reports and statistics were published, it became clear that many country towns lacked effective sanitation and mortality rates, especially those of children, were very high indeed.47The British, attempting to exonerate themselves of camp deaths, pointed this out but their comparisons have not been taken seriously in camp histories.48Again, context has tended to invalidate content.

The concentration of Boer families in the camps might be regarded as comparable to the rapid urbanisation experienced in nineteenth-century European and American industrial cities, when large numbers of rural people, with a pre-industrial culture, were concentrated in overcrowded and inadequate accommodation with few sanitary services. The fact that in South Africa this process occurred, temporarily, within the space of a few months, in the traumatic conditions of wartime, with the destruction of homes and farms, made the problems particularly acute but not necessarily different in kind. In both cases the authorities tended to blame the people concerned for the deficiencies of the system; in both cases they also attempted to reduce the mortality through a combination of improved sanitation and education. Modernisation and urbanisation are harsh the world over, as people are torn from their older, rural cultures; but it is not a reflection on the victims of change.49

Byowners and poverty

A second approach to the question of prosperity in the camps is to examine the class structure. The class-conscious British, like Dr Richard Hamilton, often remarked on the social differences amongst the inmates. Vredefort Road camp, for instance, was occupied by a "rather low class of people", "more or less uncivilized, ignorant and bitter"; the inmates of Vereeniging camp were of a "superior class".50But the Boers, too, acknowledged the presence of a lower class. Some of the middle class women considered that one of the hardships of camp life was having to live in close contact with the poor.51But it is the relative numbers of rich and poor that are at issue.

Very shortly after the war, officials began to worry about the numbers of indigent coming to the towns. As early as 1905 a commission was appointed to investigate conditions in Pretoria where a tent city had sprung up outside the town, and the following year the Transvaal Indigency Commission was established, which was nation-wide in its enquiries, despite its title.52Were these people the product of the war or did their immiseration have deeper roots?

There is a good deal of evidence to suggest both that the "poor white" phenomenon had been many decades in the making and that it was not confined to the old republics. Before the war the Dutch Reformed Church in the Cape had become increasingly concerned about the growing poverty of its congregations and the Kakamas scheme on the Orange River had been started as an experiment in rural upliftment.53In the Boer republics, well-documented processes of change had led to widespread landlessness by 1899.54Hermann Giliomee makes the startling comment that the South African Republic spent a third of its budget on poor relief.55Tim Keegan suggests that half the white rural families on the highveld were non-landowners by the end of the nineteenth century.56John Boje believes that some 35 per cent of Boers in the Winburg district might be regarded as bywoners.57

Landlessness was the product of many forces. The careless bartering of burgher-right farms for a gun or a horse meant that much land was quickly alienated, while casual occupation became more difficult as land was surveyed and fenced.58The decimation of game limited hunting as an option. The coming of the railways cut down on transport riding.59Pressure on land in the Cape Colony led many Cape people to migrate north from the 1840s, adding to the small burgher population of the republics. This northward flow was particularly prevalent in the Free State but others ventured into the Transvaal. According to the 1890 Transvaal census, at least a quarter to half of the population of every district in the Transvaal had its origins in the Cape Colony.60 If they were sufficiently wealthy, the newcomers might buy land but they also added to the bywoner population, moving onto the land of relatives who had preceded them in the trek north.61The Hon C.G. Murray, in his evidence to the Transvaal Indigency Commission, claimed that the settlers of the Soutpansberg were largely bywoners who had drifted north when they were ousted from the more prosperous south. These people were

the type of trek Boer who until the late war broke out, was quite satisfied if his daily bread for himself and his family was procurable with a minimum amount of trouble. He always kept a certain amount of large and small stock which was his worldly wealth ... His usual method of living was to spend the summer months in planting a few mealies and Kaffir corn, which he very often left his Kaffirs to reap, and in April or thereabouts to trek off to the low veld with his family and stock, shooting and laying in a stock of "biltong" for the summer, when he returned to his farm.62

The form of inheritance, in which property was divided equally amongst the spouse and the children, also contributed to growing poverty amongst the rural Boers. Farms became increasingly fragmented, occasionally to the point that by 1899, a family might inherit one thousandth of the original farm.63Such portions might become extremely long and narrow, in order to provide access to water. In 1898 in the Pietersburg district there were recently settled farms which were three miles long and only 230 yards wide.64Middelburg and Piet Retief were particularly poor areas and the occupants of the Mapochsgronden farmed tiny patches of land.65

The mineral revolution offered economic opportunities to those who were sufficiently enterprising to seize the chance. But a hallmark of poverty is conservatism, and others sank. It was the bywoners who suffered most from the expanding industrialisation of the country, and from the competition of entrepreneurial blacks.66 Added to this, in the 1890s there was the rinderpest epidemic which destroyed the cattle herds, often the sole asset of the bywoners, followed by drought. By 1899 bywoners were becoming an expensive liability although family ties and longstanding practice kept them on the land. Many Boers were hanging on to their old way of life by their fingernails. One of the most striking features that emerges from the camp registers is the number of people who lived on a single farm - sometimes half a dozen families or more, in a country in which adequate rainfall is never guaranteed and farming is often a gamble.67

With the outbreak of the war, the Boer republics had to make provision for impoverished families if their men were to go on commando. Already burdened with large welfare payments, the ZAR was now confronted by agonised requests for help from women whose husbands had died on commando, from women who could not cope without their menfolk and, presumably, from women already on relief.68 The practice of buying replacements for commando service almost certainly meant that a disproportionate number of the poor were recruited in the early days, although it is not clear how many were bought out in this way.69

Once Britain had invaded the republics, others added to the residue of existing poor. As the military governor of the ORC pointed out, the "cessation of farming and all agricultural pursuits" had so impoverished the country that scarcity, "amounting almost to famine" had to be expected.70 He gave little thought to the problem, however, remarking later that the municipalities (already in debt since taxes had not been collected) should feed their own poor. "It is a fact of war they [the poor] must look to their own private charities for support", he decided.71 Throughout the ORC local district commissioners struggled to cope with little guidance from the authorities.72 Gradually the DCs worked out a relief system, like Major Apthorp in Smithfield who eked out aid with a few bags of meal.73 The endemic poverty of the pre-war era merged into the distress that was the product of war. It is likely that these were some of the first people to be moved into the camps, since there was always a "poor relief" element to the camps.

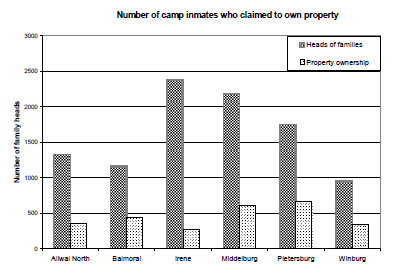

The camp records reinforce this impression of wide-spread immiseration. Of course the great majority of the camp inmates had lost their homes and almost all their possessions with the burning of the farms. Previously affluent women were forced to sleep on the ground, carry heavy burdens and cook in the rain. But this poverty did not change class consciousness or eradicate education. The newly-impoverished middle classes still struggled to maintain standards. But the camp registers also provide evidence of poverty, for the property-conscious British frequently recorded the landholdings of the families. In six very different camps the results are remarkably consistent; about 70 per cent owned no property at all.74

Moreover, much of this property was remarkable small. Amounts were recorded inconsistently but the impression is that very few owned even one entire farm; the majority owned a part share of a farm, sometimes only a few morgen. Such conclusions are consistent with the findings of the 1904 Transvaal Indigency Commission, which emphasised the fragmentation of the landholdings.75

In Balmoral, where the registers are particularly detailed, out of 1 164 families listed, 728 had no property at all (62.54 per cent). In a number of cases the farm name was listed as property but it is not clear whether this meant the ownership of an entire farm, nor do we know how large the farm was. Of the 62 who owned farms, one had six farms; two had five farms; two had four farms; eight had two farms; and 49 had one farm. A substantial number of people possessed a share in a farm, one having shares in six farms; one in three; nine in two farms; and 276 owned a single share in one farm. Again, the size of the holdings are not given. Of the specified holdings, 32 ranged from a half share of a farm to 1/9th part (one person). Twelve people gave their holdings in morgen. Only one had a really large farm - 4 500 morgen. One had 2 465 morgen, and three had about 1 000 morgen. The remainder held less than 300 morgen, including two with only sixteen morgen each. A fair number of people, 53, possessed at least one erf, usually in a town, with a small number, nineteen, having more than one erf, ranging from 20 erven (one person) to two (six people).76

In Irene camp register, out of 2 386 heads of families, only 270 claimed to own property (11.31 per cent). Of these, eight claimed multiple properties (usually a portion of a farm and an erf) and one person owned 12 000 morgen. Sixteen owned a farm. There were 52 inmates who claimed to own property although the amount was unstated, while 22 possessed a portion or a share of a farm. Eight owned half a farm, nineteen a quarter and seven a third. Ownership of between 1/5 and 1/15 of a farm was claimed by 27, of whom five owned 1/26 and one owned 1/32 part of a farm. Of those who gave actual sizes, 22 owned less than 100 morgen (some as little as ten or twelve morgen); 24 owned between 101 and 500 morgen; six owned between 501 and 1 000 morgen; and nineteen owned between 1 001 and 5 000 morgen. Two possessed 8 000 morgen.

If most of the camp inmates were bywoners and few were landowners, where were the wealthier Boers? This not an easy question to answer and is necessarily impressionistic. It needs to be recognised, however, that the British did not see the camps as prisons; they often considered them as a form of poor relief. As a result, if "refugees" could support themselves, they were encouraged to do so.77 Many went to relatives in the Cape Colony or took refuge in the coastal towns, along with the Uitlanders. A few left the country entirely. Perhaps most went to live in the villages and towns.78 There is some evidence, therefore, for arguing that the camps housed a disproportionate number of the indigent.

Respectability, identity and the denial of poverty

If the majority of the camp inmates were landless, or owned very small portions of land, why are so many people still convinced that most were middle class? The answer seems to lie largely in the post-war creation of national identity.

Although she was not part of the nationalist project, Emily Hobhouse played an important role in creating the impression that most of the camp inmates were middle class. The daughter of a clergyman, related to members of the liberal aristocracy, she came from a similar background to the members of the Ladies Committee. Like them, the cultural and moral values of the Victorian middle class were deeply embedded in her consciousness, although her political sympathies differed. But, in addition, her objective in her reports and writings was to gain the support of the British middle classes for the Boer cause. As she explained in October 1900: "I am agitating about a fund for the Burnt out wives and children of Burghers ... I am trying to obtain a 'stream of facts' wherewith to appeal to people's sympathies."79 She knew very well that accounts of the destruction of property and the suffering of genteel women would touch a cord with the middle class readership she wished to convert to her cause. In The Brunt of the War, in particular, she was careful to present Boer women as respectable and genteel.

While Hobhouse viewed the poorer camp inmates as simple country people like her father's Cornish parishioners,80 these were not the women with whom she associated. In Bloemfontein she formed a life-long friendship with Tibbie Steyn, the English-speaking wife of President Steyn. Her other associates included Mrs Blignaut, Steyn's sister; Mrs Fichardt, the wife of a prominent businessman; Mrs Krause, a member of a distinguished medical family; and Mynie Fleck, who was particularly active in camp philanthropy.81 In her letters home she often defined the women with whom she found kinship in class terms. Mrs Snyman, "a delightful woman", was a DRC minister's wife. She was "a handsome, vigorous and able woman", well travelled, and her father was the director of a bank and "very wealthy".82 Mrs Botha was the wife of the Philippolis landdrost; Mrs G. was the wife of "a prominent Free Stater"; old Mrs K., "a wealthy old lady and much respected, had been torn away from a comfortable and beautiful home to come and live in the camp".83 Wealth, respectability and good looks went hand-in-hand. The Louws were well-to-do people with a large farm and a good house. "Mrs. Louw is a delicate-looking woman with a white skin and beautiful scarlet lips so seldom seen out of books."84 Another group of women were "nearly all good-looking and brimful of patriotic fervour. Mrs Snyman is one of them and still handsome".85

While Hobhouse emphasised the gentility of the camp women and their sufferings to gain the sympathy of Britain's middle classes, she never denied the existence of a rural peasantry. In the post-war writings of Afrikaner women, however, the bywoners became increasingly invisible. Elizabeth Neethling was a key figure in this construction. As Helen Dampier noted: "Mrs Neethling insistently portrays all Boer people as affluent farm-owners and people of property and sensibility and she sees the 'mistreatment' of Boers in the camps as particularly reprehensible because these were wealthy, civilised people."86 A member of the Murray family, married to Ds H.L. Neethling and closely associated with pro-Boer movements in the Cape, Neethling played a major and complex role in the creation of a camp mythology.87As Stanley notes, she depicted pre-war republican life as a prosperous Eden. The typical Boer home was both idyllic and very Victorian:

We are ushered into a sitting-room, a carpet on the floor and numerous rugs, white or dyed, in various colours, skins of the silky angora goat. Lace curtains to the windows, a sofa, bentwood and upholstered chairs, small tables, vases of flowers, photos in frames, some bits of fancy-work, pictures on the walls, and, last but not least, a good American organ. An air of comfort about it all.88

Neethling had little sympathy for the bywoners for whom she seems to have felt only distaste.

Think what it must be for a lady of refined feeling to live in one room with an unrefined family. To eat, sleep, dress, sew, write - all in that one apartment. No privacy, no quiet. What is spoken in one room can be heard in the next. From five o'clock in the morning till ten at night an incessant din. Absolute misery to a lady who had lived on her own farm, in a house commodiously built of stone, containing six or eight rooms.89

Neethling's comment allows us a glimpse into social relationships between landowner and bywoner which had not always been harmonious before the war and deteriorated further afterwards, as the "social web of authority" in Boer communities began to wear thin.90

But it was not only the cultural entrepreneurs who depicted the camp inmates as civilised ladies for there is other evidence of affluence as well. When soldiers described their enjoyment of destruction and looting, they often emphasised the substance and beauty of the homes they were burning. One wrote:

We used to have plenty of fun. All the rooms were ransacked. You can't imagine what beautiful things there were there - copper kettles, handsome chairs and couches, lovely chests of drawers, and all sorts of books. I've smashed dozens of pianos.91

Another remarked on the library, with books in Dutch and English.92 The ravages were compared to the Scottish clearances. "We moved on from valley to valley 'lifting' cattle and sheep, burning, looting, and turning out the women and children to sit and cry beside the ruins of their once beautiful farmsteads."93 One reason why these soldiers' accounts overwhelmingly describe the destruction of good homes, however, is that there no drama in the looting and destruction of poorer homes. As so often, poverty is silenced, one suspects.94 Nevertheless, the evidence that camp people were middle class is so overwhelming that, using these testimonies and accounts, it is easy to see why most people still believe that the camp inmates were prosperous people.95

It would, however, be a very unusual society at the end of the nineteenth century in which the landed and the affluent were predominant. Poverty was the fate of most people in late nineteenth-century Europe and America and much of the cause of the social turmoil of the first half of the twentieth century lay in economic disparity and dispossession. The skewed nature of South African society, in which whites have formed an upper class, has perhaps blinded some to the improbability of such a social structure. There is another, more inchoate, factor as well. As my angry correspondent implied, lacking the tradition of a respectable working class, or Australia's convict origins, white South Africans tend to believe that their ancestors were well born. Somewhere in their past lurks an aristocrat.96 The denial of poverty, which is partly racist in its origins, runs deep in white South African society.

Hermann Giliomee correctly notes that for poverty to be eradicated, it has first to be recognised.97 In Britain this discovery had been at work through most of the nineteenth century, from the movement which led to the enactment of the 1834 Poor Law, to the investigations of Henry Mayhew and Charles Booth, and the welfare legislation which was introduced in the early twentieth century. For Victorians poverty was a source of shame but by 1900, the emergence of socialism had begun to reshape attitudes to poverty. The poor began to be seen as victims of capitalism rather than originators of their own misfortune.98

South Africa, however, was a long way from adopting this frame of thought, denying the need for welfare legislation.99In the new colonies the British led the first investigations into the poor white problem. In 1905 a commission was established to investigate the "undesirable influx" of poor whites gathering on the fringes of Pretoria. They were, the commission believed, ill-fitted for town life.100 The Transvaal Indigency Commission followed the next year. Indigents were defined as those in actual want of the necessaries of life, including "loafers, vagrants, and members of the semi-criminal class - the lazy and the vicious". The second class were those with just enough to live on but were "so ignorant or lazy, and live at such low standards", that they were easily tipped into poverty. These people were to be found mainly amongst the country population of the Transvaal.

They have fallen behind in the march of civilisation, and are, generally speaking, without any real knowledge of farming or of any skilled trade. They have formed no habits of industry, live a hand-to-mouth existence, and accumulate no reserves, so that any sudden misfortune, such as the failure of a crop, at once brings them to the brink of starvation. They are likely in any case to become destitute in course of time through shiftlessness and lack of foresight.101

The cast of mind which framed poverty in these terms served to reinforce middle class distaste for the poor.

Isabel Hofmeyr was one of the first historians to link this process of the disintegration of the traditional community to the Afrikaner nationalist project. The collapse of the bywoner way of life and the drift to the towns, she noted, contributed to the erosion of traditional family structures. Large number of people deserted the Dutch Reformed Churches for the new apostolic sects, while the ability of young women, in particular, to find employment, dented old patriarchal controls. As the family came under stress, middle class "moral brokers" were alarmed. In the Transvaal, these "moral brokers", consisting of an Afrikaner petty bourgeoisie of journalists, clerks, clerics, small farmers and teachers, were increasingly alienated from Het Volk, dominated by wealthy farmers. Instead they sought political support amongst the newly-urbanised populace. In doing so, they embarked "on a programme of rediscovering and reconsolidating" their old congregations and constituencies. Hofmeyr's concern is the making of Afrikaans but, in passing, she also notes that "as good middle-class citizens" these people were actively engaged in welfare work; there was, she emphasises, a "simultaneity of middle-class philanthropic 'intervention' and nationalist innovation."102

It is this philanthropic intervention that is of interest here, for it was also closely associated with the post-war construction of the volksmoeder. Women were central to the project of saving the volk because it was women who socialised their children as Afrikaners.103 While earlier writers tended to see the construction of the volksmoeder as a male project, recent writers have emphasised the agency of Afrikaans women.104 The task of "saving" Afrikaans women for the volk also involved the modernisation of Afrikaans culture. Despite the idealisation of the women in such volumes as Postma's Die Boervrou, women's organisations and magazines like Die Boerevrouw, were concerned with the re-education of both urban working class and rural women.105 Articles in Die Boerevrouw, Hofmeyr notes, drew on a "domestic science ideology" which "attempted to permeate housework with a modern, 'scientific' ethos".106 This work of refashioning the "fractious bywoners" was conducted, Hofmeyr suggests, by a "group of moral agents" whose labour was "aided by borrowing from imperial thinking on social engineering of various types".107 Indeed, whatever the political and cultural divisions between British and Boer, these people often shared notions about domesticity, the ideal home, the ideal mother - and respectability. For both, poverty was humiliating and demeaning; the poor were stigmatised as "pauperised" at best and were often associated with viciousness, criminality and degeneration.

Part of this project also involved a new emphasis on mothering.108The ideal Afrikaans mother also created a middle class home. In her first editorial justifying the launch of Die Boervrou Mabel Malherbe wrote:

Should a woman manage her house with knowledge, knowledge of hygiene and domestic science, and should she implant in her children a bias to work with the knowledge on every terrain, to leave nothing to chance, then her children must be successful, achieving much for country and volk.109

Like the Victorians, reforming middle class Afrikaners valued respectability, the new domesticity, and cleanliness. In South Africa, however, there were racist undertones to this construction for twentieth-century Afrikaners, claiming a political independence which emphasised the kinship with civilised Europe, rather than with "barbaric" Africa. The controversy surrounding the publication of the SAJS article suggests that this construction remains potent.

The upliftment of the Afrikaner poor white and the creation of Afrikaans as a language of culture and learning, is one of the great success stories of the twentieth century. It is South Africa's tragedy that it was achieved at the expense of blacks but it has left an inspiring legacy. South Africa is the loser if the full extent of this achievement is brushed away by a denial of the past.

The author is an Honorary Research Associate in the Department of Historical Studies, University of Cape Town. Email: evh@iafrica.com. She is currently engaged in research on the concentration camps of the South African War and has published a number of articles, of which the most recent is "A Tool for Modernization? The Boer Concentration Camps of the South African War, 1899-1902", South African Journal of Science, 106, 5/6, 2010, pp 58-67. I should like to acknowledge gratefully the financial support of the Wellcome Trust who is not responsible for my opinions. My thanks also to Dr Iain Smith for his support and stimulation.

1.Van Heyningen, "A Tool for Modernization?, pp 58-67; Rapport, 19 June 2010. [ Links ]

2. Die Burger, 3 July 2010

3. E. van Heyningen, "The Concentration Camps of the South African (Anglo-Boer) War, 1899- 1902", History Compass, 6, 2008, online at http://www.blackwell-compass.com/subject/ history/ Since the publication of this article several excellent theses with a bearing on the camps have been completed including J.G. Boje, "Winburg's War: An Appraisal of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 as it was Experienced by the People of a Free State District", PhD thesis, University of Pretoria, 2009; W.J. Pretorius, "Die Britse Owerheid en die Burgerlike Bevolking van Heidelberg, Transvaal, gedurende die Anglo-Boereoorlog", PhD thesis, University of Pretoria, 2007.

4. E. van Heyningen, "Costly Mythologies: The Concentration Camps of the South African War in Afrikaner Historiography", JSAS, 34, 3, September 2008, pp 495-513. [ Links ]

5. W.I. Direko et al., Suffering of War: A Photographic Portrayal of the Suffering in the Anglo-Boer War Emphasising the Universal Elements of All Wars (Kraal Publishers, Bloemfontein, 2003). [ Links ]

6. Personal email, 17 June 2010.

7. Cd 819, Reports etc on the Working of the Refugee Camps in the Transvaal, Orange River Colony, Cape Colony and Natal (H.M.S.O., London, 1901); Cd 853, Further Papers Relating to the Working of the Refugee Camps in the Transvaal, Orange River Colony, Cape Colony, and Natal (H.M.S.O., London, 1901); Cd 902, Further Papers Relating to the Working of the Refugee Camps in the Transvaal, Orange River Colony, Cape Colony, and Natal (H.M.S.O., London, 1902); Cd 934, Further Papers Relating to the Working of the Refugee Camps in South Africa (H.M.S.O., London, 1902); Cd 936, Further Papers Relating to the Working of the Refugee Camps in South Africa (H.M.S.O., London, 1902); Cd 893, Report on the Concentration Camps in South Africa by the Committee of Ladies (H.M.S.O., London, 1901).

8. P.M. Krebs, Gender, Race, and the Writing of Empire. Public Discourse and the Boer War (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999); E. Harrison, "Women Members and Witnesses on British Government Ad Hoc Committees of Inquiry 1850-1930, with Special Reference to Royal Commissions of Inquiry", PhD thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science, 1998, p 163. Krebs suggested that the appointment of the Committee was an important step on the road to women's participation in public life. [ Links ]

9.Harrison, "Women Members and Witnesses", p 156.

10. The Blue Books consist of some correspondence and the first camp reports. Dr Iain Smith checked the Blue Books against the originals and established that almost nothing was removed except for the item cited on p 6 (fn 29).

11. Cd 819, pp 162-166.

12. Dictionary of South African Biography, Volume 5 (Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria, 1987), pp 277-278. [ Links ]

13. Johanna van Warmelo (Brandt) deserves a biography but, one would hope, a disinterested biographer. She was infuriatingly self-absorbed and dramatic but she obviously possessed great charm. General Maxwell, Dr Franks and, of all people, the austere Sir Patrick Duncan, clearly fell under her spell. For a corroboration, to an extent, of Franks' comments see J. Grobler (ed), The War Diary of Johanna Brandt (Protea Book House, Pretoria, 2007). For Van Warmelo's response see E.H. Hobhouse, The Brunt of the War and Where it Fell (Methuen, London, 1902), p 184.

14 Cd 819, p 163.

.15 E. van Heyningen, "Women and Disease: The Clash of Medical Cultures in the Concentration Camps of the South African War", in G. Cuthbertson, A. Grundlingh and M-L. Suttie (eds), Writing a Wider War: Rethinking Gender, Race, and Identity in the South African War, 1899- 1902 (Ohio University Press and David Philip, Athens and Cape Town, 2005), pp 186-212. [ Links ]

16. See, for example, Dr John Hunter of Kimberley camp and Dr Rossiter of Harrismith camp. Online at http://www.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/Histories/Kimberley/; and http://www.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/Histories/Harrismith/ (accessed 16 October 2010).

17. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online at www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/33096 (accessed 29 September 2010). [ Links ]

18. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

19. L. Bean and E. van Heyningen (eds), The Letters of Dr Jane Elizabeth Waterston, 1868-1905 (Van Riebeeck Society, Cape Town, 1983). [ Links ]

20. University of London, LSE 2/11, Streatfield Collection, Lucy Deane letters, 4 October 1901. Giliomee, for instance, repeats the charge that the Ladies Committee failed to visit black camps. See H. Giliomee, The Afrikaner: Biography of a People (Tafelberg, Cape Town, 2003), p 255.

21. Harrison, " Women Members and Witnesses", p 329.

22. Harrison, " Women Members and Witnesses", p 278.

23. As an example of the kind of networks that existed, Dr Jane Waterston had studied under Dr Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Millicent Garrett Fawcett's sister, and had been a close friend of Edmund Garrett, the editor of the Cape Times and a cousin of Anderson and Fawcett.

24. Lucy Deane letters, 23 December 1901.

25. Hermann Giliomee comments on the "two faces of British imperialism", the one liberal and modernising, the other aggressive and condescending to other cultures. The first had been embraced by such Afrikaners as Andrew Murray, moderator of the Dutch Reformed Church: The Afrikaners, pp 232-233.

26. A.L. Stoler and F. Cooper, "Between Metropole and Colony"; in F. Cooper and A.L. Stoler, Tensions of Empire: Colonial Cultures in a Bourgeois World (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1997), p 5. [ Links ]

27. Stoler and Cooper, "Between Metropole and Colony", pp 12, 31. The SAJS article was an attempt to explore these ideas in the context of the camps.

28. C. Hall, "Of Gender and Empire: Reflections on the Nineteenth Century", in P. Levine (ed), Gender and Empire (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004), p 47. [ Links ]

29. J.C. Otto, Die Konsentrasiekampe (Protea Boekhuis, Pretoria, 2005, orig. 1954), p 139. These were amongst the few lines censored from any of the published material on the camps. Note the conflation of health, good looks and desirable femininity. See my comments on Hobhouse below, fn 84.

30. B. Haley, The Healthy Body and Victorian Culture (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1978); [ Links ] W.E. Houghton, The Victorian Frame of Mind 1830-1870 (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1957), p 41. [ Links ]

31. Houghton, The Victorian Frame of Mind, pp 184-185. For a fascinating exploration of gentility in the Victorian middle classes, see L. Davidoff and C. Hall, Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the Victorian Middle Class 1780-1850 (Hutchinson, London, 1987). Both these authors are looking at the emergence of these ideas; by 1900 they had hardened and shifted but, for the purpose of this argument, the points they make remain useful.

32. The readable reports of David Murray of Belfast camp are an example of a man who was struggling in his task, but was doing his best to present a good face. More efficient superintendents, like B. Graumann of Barberton camp, often presented terse reports. See http://www.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/index.php (accessed 16 October 2010).

33. One has only to remember the way in which Americans rallied solidly round President George W. Bush after Iraq was dubiously invaded in 2003.

34 .Lucy Deane letters, 23 December 1901.

35.C. Headlam (ed), The Milner Papers: South Africa 1899-1905, 2 (Cassell, London, 1933), p [ Links ]

36. My thanks go to Dr Iain Smith for drawing my attention to the argument below.

37. D. Low-Beer, M. Smallman-Raynor and A. Cliff, "Disease and Death in the South African War: Changing Disease Patterns from Soldiers to Refugees", Social History of Medicine, 17, 2, 2004, pp 223-245; P. Curtin, Disease and Empire: the Health of European Troops in the Conquest of Africa (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997), p. 210; J.C. de Villiers, Healers, Helpers and Hospitals: A History of Military Medicine in the Anglo-Boer War, Volume 2 (Protea Book House, Pretoria, 2008), p 111.

38.Typhoid, now usually known as Salmonella, is a complex disease. Its symptoms are not always immediately obvious and it can be transmitted by carriers who are perfectly well. "Typhoid Mary" is the classic example. For many years it was confused with typhus, "gaolfever" a lice-born disease which is a disease of overcrowding and was common in the German concentration camps. Anne Frank, for instance, died of typhus. Typhus was little known in South Africa until the twentieth century, unlike typhoid which became a growing problem as South Africa urbanised at the end of the nineteenth century. For the Cape Town example see E. van Heyningen, "Public Health and Society in Cape Town, 1880-1910", PhD thesis, University of Cape Town, 1989, p 459. Terminology is a nightmare for lay people. My Afrikaans dictionary distinguishes between buiktifus (typhoid) and tifus (typhus) while enteric (the same disease, as opposed to enteritis) is given as ingewandskoors (also given as an alternative for typhoid). Unfortunately such distinctions are rarely made in references to the camps where tifus is applied to both diseases. Consequently Afrikaans translations (and back into English) of causes of camp mortality should be used with caution.

39. http://chestofbooks.com/health/nutrition/Dietetics-4/Diet-In-Typhoid-Fever.html (accessed 10 August 2010).

40. A. Cliff, P. Haggett, and M. Smallman-Raynor, Measles: An Historical Geography of a Major Human Viral Disease from Global Expansion to Local Retreat, 1840-1900 (Blackwell, Oxford, 1993). There is almost no reference to the camps epidemic in this classic study. [ Links ]

41. In Cd 819 alone, references to the insanitary practices of the Boers is to be found on pages 46, 92, 101, 104, 125, 135, 140, 145, 163, 166, 201, 213-214, 216, 238, 241, 267, 274, 303, 325, 327, 331, 333, 354, 381.

42. Van Heyningen, "A Tool for Modernisation?", pp 63-64. [ Links ]

43. Cd 819, p 241. For corroboration see fn 91 and quotation.

44. Cd 819, p 274.

45. I Smith (ed), The Siege of Mafeking, Volume 1 (The Brenthurst Press, Pretoria, 2001), pp 78-79. [ Links ]

46. On the extent of infectious disease amongst the Boer prisoners of war, see De Villiers, Healers, Helpers and Hospitals, Volume 1, pp 248, 403-404.

47. C. Simkins and E. van Heyningen, "Fertility, Mortality and Migration in the Cape Colony, 1891-1904", The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 22, 1, 1989, pp 79-111. [ Links ]

48. Cd 902, pp 13-18; Cd 893, p 14.

49. On the traumatic process of urbanisation for Afrikaners in the twentieth century, see Giliomee, The Afrikaners, p 323.

50. Free State Archives Repository (hereafter FSAR), Superintendent Refugee Camps (hereafter SRC) 9/RC3244, Enclosing papers concerning interference in camp routine at Vredefort Rd, 10 July 1901; SRC 22/RC8215, Refugee camps training of nurses, 21 March 1902; Cd 819, p23.

51. See for example Elizabeth Neethling below; and E. Neethling, Should We Forget? (HAUM, Cape Town, c.1902), p 16.

52. TG 13-1908, Report of the Transvaal Indigency Commission (Government Printer, Pretoria, 1908).

53. Giliomee, The Afrikaners, p 320.

54. R. Morrell, (ed), White but Poor: Essays on the History of Poor Whites in Southern Africa 1890-1904 (Unisa, Pretoria, 1992); J. Bottomley, "Public Policy and White Rural Poverty in South Africa, 1881-1924", PhD, Queen's University, 1990, pp 60-145; C. Bundy, "Vagabond Hollanders and Runaway Englishmen: White Poverty in the Cape before Poor Whiteism", in W. Beinart, P. Delius and S. Trapido (eds), Putting a Plough to the Ground: Accumulation and Dispossession in Rural South Africa, 1850-1930 (Ravan, Johannesburg, 1986), pp 101- 128. Amongst the most insightful articles is I. Hofmeyr, "Building a Nation from Words: Afrikaans Language and Ethnic Identity, 1902-1924", in S. Marks and S. Trapido, The Politics of Race, Class and Nationalism in Twentieth-Century South Africa (Longman, London, 1987), pp 99-103.

55. Giliomee, , p 316; Bottomley, "Public Policy", p 61.

56. T.J. Keegan, Rural Transformations in Industrializing South Africa: The Southern Highveld to 1914 (Ravan, Braamfontein, 1986), 21; Giliomee, The Afrikaners, p 321. [ Links ]

57. Boje, "Winburg's War", p 183.

58. Giliomee, The Afrikaners, p 180; J.F.W. Grosskopf, Rural Impoverishment and Rural Exodus, Volume 1 (The Carnegie Commission, Stellenbosch, 1932), pp 38-39.

59. Keegan, Rural Transformations, pp 20-29. A few camp inmates still gave transport riding as their occupations.

60. Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, Uitslag van de Volkstelling Gehouden in de Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek den 1stden April 1901... (Pretoria, Staatsdrukkerij, 1891). [ Links ]

61. D.M. Goodfellow, A Modern Economic History of South Africa (Routledge, London, 1931), pp 54-55. Few historians mention this northward expansion but for examples see C. van Onselen, The Seed is Mine: The Life of Kas Maine, a South African Sharecropper, 1894-1985 (David Philip, Cape Town, 1996), p 21; C. du Plessis, Notes Written during the War between England and the Transvaal, 1899-1900 (SA National Museum of Military History, Johannesburg, 2001), Introduction; Grosskopf, Rural Impoverishment, p 37; J.C.G. Kemp, Vir Vryheid en Vir Reg (Nasionale Pers, Cape Town, 1941), p 167.

62. TG 13-1908, Report of the Transvaal Indigency Commission, p 382. See also R.W. Schikkerling, Commando Courageous. (A Boer's Diary) (Hugh Keartland, Cape Town, 1964), pp 299, 350-351, 360-361.

63. Grosskopf, Rural Impoverishment, p 121.

64. Grosskopf, Rural Impoverishment, p 120.

65. R. Morrell, "The Poor Whites of Middelburg, Transvaal, 1900-1930: Resistance, Accommodation and Class Struggle", in Morrell, White but Poor, pp 1-28. [ Links ]

66. W.M. Macmillan, The South African Agrarian Problem and its Historial Development (CNA, Johannesburg, 1919), pp 38-39; 68-72; [ Links ] S. Swart, '"Desperate Men': The 1914 Rebellion and the Politics of Poverty", South African Historical Journal, 42, May 2000, pp 162-168; Keegan, Rural Transformations, pp 51-95. [ Links ]

67. http://www.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/index.php (accessed 16 October 2010).

68. J.D. Ploeger, Lotgevalle van die Burgerlike Bevolking gedurende die Anglo-Boereoorlog 1899-1902, Volume 1 (Staatsargiefdiens, Pretoria, 1990), p 6; L. Grundlingh, "Another Side to Warfare: Caring for White Destitutes during the Anglo-Boer War (October 1899-May1900)", New Contree, 45, 1999, pp 137-163.

69. B. Nasson, The War for South Africa: The Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902 (Tafelberg, Cape Town, 2010), p 84. Giliomee notes that many of the bywoners resented the exploitation of the past, which had forced them to go to war, leaving their families destitute. "Their treason was often a rebellion against exploitation", he comments: The Afrikaners, p 251. [ Links ]

70. National Archives UK (hereafter NAUK), Colonial Office (hereafter CO) 879/70/664, 4259, no 135, 17 January 1901, p 163, published in Cd 547, no 42.

71. FSAR, Military Governor (hereafter MG) 3-4, Major Bodé for DC, Wepener, 7 June 1900.

72. FSAR, MG 3-4, Mrs Helena Strauss, Annie's Dale, Wepener - Lord Roberts and attached report, 15 June 1900; Mrs E. Bower, Runnymede, Wepener - Military Governor, Bloemfontein, 27 July 1900; Major F. White - Military Governor, Bloemfontein, 4 May 1900; MG 2, A. Hume, DC Smithfield - Military Governor, Bloemfontein, 18 July 1900; MG 4 and 5, D.H. Fraser, Wepener - H. Pearce, Bloemfontein, 24 September 1900.

73. FSAR, MG 2, Major K.P. Apthop - Military Governor, 24 September 1900. For other examples see MG 3, Captain G.H. Grant - Assistant to Military Governor, 18 June 1900; H.A Broome to the DC, Hoopstad, 26 September 1900.

74. National Archives of South Africa, Pretoria (hereafter NASA), Director Burgher Camps (hereafter DBC) 46, 47, 48, 49, Balmoral camp registers; DBC 62, Irene camp register; DBC 82, 83, 84, Middelburg camp registers; DBC 87, 88, 89, Pietersburg camp registers; FSAR, SRC 69, Aliwal North camp register; SRC 90, Winburg camp register. The only criteria for the selection of these camps is that the entries lent themselves to analysis. While some registers only recorded property, a number, like Balmoral, specifically stated "no property".

75. TG 13-1908, annexures.

76. NASA, DBC 46, 47, 48, 49, Balmoral camp registers.

77. See the Pietersburg registers, particularly, for an example of a situation where inmates left the camp for the town, and returned when their money ran out. NASA, DBC 87 and 88.

78. For one example see Du Plessis, Notes Written during the War.

79. J.H. Balme, (Hobhouse Trust, Cobble Hill, 1994), p 50.

80. R. van Reenen, Emily Hobhouse: Boer War Letters (Human & Rousseau, Cape Town, 1984), p 95. [ Links ]

81. Van Reenen, Letters, p 68; [ Links ] K. Schoeman, Bloemfontein: Die Ontstaan van 'n Stad 1846-1946 (Human & Rousseau, Cape Town, 1980), illus. no 86. [ Links ]

82. Hobhouse, Brunt of the War, pp 90, 226.

83. Van Reenen, Letters, p 76; Hobhouse, Brunt of the War, pp 231, 258.

84. Van Reenen, Letters, p 90. See my comment above on the conflation of health, virtue and good looks, fn 29.

85. Van Reenen, Letters, p 92.

86. H. Dampier, "Women's Testimonies of the Concentration Camps of the South African War: 1899-1902 and after", PhD thesis, University of Newcastle, 2005, p 31. [ Links ]

87. L. Stanley and H. Dampier, "Cultural Entrepreneurs, Proto-nationalism and Women's Testimony Writings: From the South African War to 1940", JSAS, 33, 3, September 2007, p 510; [ Links ] Dampier, "Women's Testimonies", pp 338-347; L. Stanley, Mourning Becomes ... Post/Memory, Commemoration and the Concentration Camps of the South African War (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2006), pp 105-114. [ Links ]

88. Neethling, Should We Forget?, p 10.

89. Neethling, Should We Forget?, p 78.

90. Hofmeyr, "Building a Nation from Words", pp 99-100.

91. Hobhouse, Brunt of the War, p 97.

92. Hobhouse, Brunt of the War, p 10.

93. Hobhouse, Brunt of the War, p 41.

94. Although I have not searched systematically for such accounts, I have come across only one reference to the destruction of bywoner homes. See T. Jackson, The Boer War (Channel Four, London, 1999), p 124.

95. Die Burger article is accompanied by a photograph of a well-dressed family surrounded by their possessions. In Suffering of War very similar photographs are described as "propaganda": Direko, Suffering of War, p 129. For another perspective see M. Godby, "Confronting Horror: Emily Hobhouse and the Concentration Camp Photographs of the South African War", Kronos, 32, November 2006, pp 34-48.

96. Apart from the correspondent cited above, I have little direct evidence for this statement but the chairman of Western Cape branch of the South African Genealogical Society made this observation to me recently. A past curator of the Albany Museum in Grahamstown said the same thing of English-speaking settler descendents.

97. Giliomee, The Afrikaners, p 315.

98. The literature on this subject is huge but see, for instance, the classic G.S. Jones, Outcast London: A Study in the Relationship between Classes in Victorian Society (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1971).

99. See, for instance, Van Heyningen, "Public Health and Society in Cape Town", pp 412-437.

100. M. Wilson and L. Thompson, The Oxford History of South Africa, Volume 2 (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1971), p 182. [ Links ]

101. TG 13-1908, pp 3-4.

102. Hofmeyr, "Building a Nation from Words", pp 100-103.

103. Hofmeyr, "Building a Nation from Words", p 113.

104. E. Brink, "Man-made Women: Gender, Class and the Ideology of the Volksmoeder", in C. Walker (ed), Women and Gender in Southern Africa to 1945 (David Philip, Cape Town, 1990), pp 273-292; [ Links ] Stanley and Dampier, "Cultural Entrepreneurs", pp 501-519; L-M. Kruger, "Gender, Community and Identity: Women and Afrikaner Nationalism in the Volksmoeder Discourse of Die Boerevrou (1919-1931)", MA thesis, University of Cape Town, 1991. [ Links ]

105. W. Postma, Die Boervrou: Moeder van haar Volk (Nasionale Pers, Bloemfontein, 1918); [ Links ] M. du Toit, "The Domesticity of Afrikaner Nationalism: Volksmoeders and the ACVV, 1904- 1929", JSAS, 29, 1, 2003, pp 155-176. [ Links ]

106. Hofmeyr, "Building a Nation from Words", p. 114.

107. Hofmeyr, "Building a Nation from Words", p. 115.

108. Kruger, "Gender, Community and Identity", p 202; M. du Toit, "'Gevaarlike Moederskap': the ACVV and the Management of Childbirth, 1925-1939", Women and Gender in Southern Africa Conference, Durban, 30 January to 2 February 1991. [ Links ]

109. Kruger, "Gender, Community and Identity", p 170.