Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Dental Journal

versión On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versión impresa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.79 no.1 Johannesburg feb. 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sadj.v79i01.16613

RESEARCH

Oral health care service delivery in schools for special needs in eThekwini District, KwaZulu-Natal

Sinenhlanhla GumedeI; Shenuka SinghII; Mbuyiselwa RadebeIII

IBDentTher, MMedSc, PGDip in Public Health, School of Health Sciences, Discipline of Dentistry, University of KwaZulu-Natal ORCID: 0009-0008-6171-9867

IIPhD, PhD, School of Health Sciences, Discipline of Dentistry, University of KwaZulu-Natal ORCID: 0000-0003-4842-602X

IIIMbuyiselwa Radebe, PhD, Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Dental Sciences, Durban University of Technology ORCID: 0000-0001-7201-1524

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Caries and gingival disease are prevalent oral health issues affecting more than 80% of school-going children including those with special needs attending special schools. Schools play a crucial role in promoting oral health, providing education and identifying issues early. These school-based health programmes are essential for addressing these issues and can reach more than 1 billion children worldwide, as well as school staff, families and the community.

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES: To determine the current delivery of oral health care programmes in the identified special schools by means of a semi-structured interview with school managers.

DESIGN: A descriptive qualitative study design.

METHODS: All school managers (principals) who were responsible for the facilitation of the implementation and delivery of oral health services in each of the 22 special schools were invited to participation in the study. Purposive sampling was used to select the managers at the various special schools. Data collection comprised face-to-face, semi-structured interviews to explore the specific provision of oral health-related interventions and programmes (1 interview was conducted per school, n=22).

RESULTS: Six emergent themes were present in the study: oral health activities, implementation and evaluation process, implementation challenges, policy content perceptions, dental examinations and oral health prevalence in special schools. Oral hygiene was identified as a priority, with educators and school nurses responsible for school oral health education, supervised teeth brushing programme, pain management, oral examinations in some cases and referral for dental treatments through engaging parents, learners and health workers in oral health promotion, which was supported by the school's health policy with the departmental heads responsible for programme evaluation. However, the implementation of the programmes was impacted by five factors: lack of parental support, lack of professional guidance, lack of resources, lack of support from the oral health department and the Covid-19 pandemic further exacerbated these challenges.

CONCLUSION: The study reveals that special schools have preventative and promotive oral health programmes, but they need therapeutic or curative services to address unmet treatment needs. Factors affecting these programmes have led to gaps in implementation processes. Together, these findings point to an urgent need for a review of oral health care programmes in KwaZulu-Natal special schools to ensure proper support and collaboration between key stakeholders to reduce negative effects and improve overall oral health programmes.

INTRODUCTION

Every day, learners with special needs deal with the negative effects of each of their unique disabilities, including the manner in which these effects impact their oral health.1 The South African National Oral Health Policy, which presents measures to address learners' oral health needs in school settings, the Integrated School Health Policy document (2012) and the School Health Policy and Implementation Guidelines (2011) all suggest that learners' oral health needs are to be identified and addressed through targeted services offered to specific age groups.2-6 These include oral health screening, fissure sealant placement on permanent molar teeth, fluoride varnish treatments and the administration of Atraumatic Restorative Technique (ART).7

Oral health-related problems, namely caries and gingival disease, are among the most widespread conditions in the human population, affecting more than 80% of school-going children. This has been noted in the special schools as well. A study conducted in Turkey reported 84% of decayed teeth among individuals with disabilities.8 Furthermore, the oral hygiene status of participants was poor, with heavy plaque accumulation found in approximately one in three subjects.8 The results reported that people with intellectual disabilities had poorer oral health. This included greater numbers of tooth extractions, more caries, fewer fillings, greater gingival inflammation, greater rates of edentulism, had less preventative dentistry and poorer access to services when compared to the general population.9,10 According to a study conducted on children with special health care needs in Ile-Ife, Nigeria, the majority of the decayed teeth were left untreated and 49.0% had progressed to involve the pulp.11 Contrary to these findings, a study conducted in Johannesburg, South Africa (SA) reported that children with special health care needs had lower caries prevalence compared with the general population, However, they also had higher unmet treatment needs regardless of their type of disability.12

Many oral health conditions are preventable and reversible in their early stages.13 However, there is a lack of reported awareness among learners, parents, caregivers and educators on the causes and prevention of oral disease (particularly in people with special needs). The disability also makes most of these individuals dependent on parents, siblings and caregivers for general care as well as oral hygiene, especially among the young, severely impaired and institutionalised.14 Most of these caregivers may not have the necessary knowledge to recognise the importance of oral hygiene and proper diet. This lack of knowledge may result in these individuals being pampered with unhealthy food or cariogenic snacks, eventually disregarding oral hygiene practices and failing to seek necessary oral care as recommended.15 There are 1,179 schools in SA of which 464 (40%) are special needs schools and 14% (64) of those special schools are located in KwaZulu-Natal.16 Schools are one of the important settings for oral health promotion, oral health education and early identification of oral health-related issues. Schools can reach more than 1 billion children worldwide - this could also involve the school staff, families as well as the community at large.3 This is normally accomplished through school-based health programmes. SA has recognised the value of school-based interventions that include oral health initiatives.17 However, the evidence is lesser in special schools.

This iterates the need for preventive measures and improved access and availability of oral health clinical care for children with special needs.18 The school environment is capable of carrying out combined preventive and promotive oral health programmes provided these are adequately funded with sufficient resources.17 Therefore, there should be an emphasis on appropriate oral health promotion activities for individuals with special needs. Such activities could include improving the health literacy and quality of care to caregivers, and providing the dental team with specialised training related to special needs dentistry.19 The school environment as part of the health promotion settings approach, therefore, requires further interrogation to determine the viability of offering such services.

This study is part of a bigger study which aims to determine oral health needs for school-going children with disabilities in KwaZulu-Natal eThekwini district. This will be achieved through a systematic collection of commonly occurring oral health-related epidemiological data, as well as by implementing and evaluating an oral health promotion intervention in selected schools, so as to inform a framework for oral health care for children with special needs. However, the objective of this paper was to determine the current delivery of oral health care programmes in the identified schools by means of a semi-structured interview with school managers. This was conducted to assess the extent to which oral health care programmes are implemented and evaluated within the special needs schools located in eThekwini district. The study concentrated on these four major categories: Oral health policy, oral health programmes, contextual variables influencing oral health promotion and prevalence of oral conditions.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Study design

An exploratory study design was used for the qualitative data collection of this study.

Setting

Participants in this study were school managers (principals) chosen from a community of special schools in the eThekwini district, KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), South Africa.

Study participants

All school principals were invited to participate in the study. These managers were responsible for the facilitation of the implementation and delivery of oral health services in each of the 22 special schools that gave consent to participate in the study.

Study size

Purposive sampling was used to select the managers at the various special schools. The inclusion criteria included all identified school principals who had been at least employed in the identified special school for a minimum period of one year in order for them to have a clear understanding of how the school runs (n=22).

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the University of KwaZulu-Natal's Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC00003814/2022) and ethical procedures were followed to protect data confidentiality. The KZN Department of Education granted the gatekeeper permission to access the study participants.

Data sources/measurement

Data collection comprised a face-to-face, semi-structured interview with 22 principals who volunteered to participate in the study; one interview was conducted per school. The purpose of the interview was to explore specific oral health priorities of the facilities' provision of health interventions, screening programmes for oral disease identification, policy statements on oral health care, integration of oral health into general healthcare within the primary healthcare (PHC) system and the dietary practice at school. The interview schedule included questions such as: Does the special school have a comprehensive oral health promotion programme? If yes, who is responsible for its implementation? How do budgets affect the implementation and sustainability of the programme? List all oral health services and oral health promotion provided by the facility. Which methods are used to evaluate your oral health promotion programmes? The questions also include further probes such as: What evidence is available in terms of statistical annual reports or records to prove or support that oral health programmes are included and implemented in the school? and What are the barriers and challenges facing the staff in implementing oral health promotion? which were used to obtain responses in knowledge and comprehension.

For the data collection procedure, interviews were conducted with the identified school principals as per their choice and availability. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the interview commenced. The audio recording was only done when permission was obtained from the interviewee and after all issues of confidentiality were explained. The researcher was engaging with participants by impartially presenting questions, while paying close attention to participants' responses, for approximately 30 minutes in duration, from August to September 2022. Field notes were made after the interviews.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the qualitative data, the analysis was inductive. Responses from interviews were transcribed verbatim and checked for quality. The initial set of codes representing the meaning and patterns were refined and coded. Links were formed between the codes and supporting data, codes were further grouped into themes and the themes were reviewed and revised. The conclusions drawn from the analysed data and the results were then presented as a narrative. The data analysis process was conducted in four stages - finding initial concepts, coding the data, sorting the data by theme and interpreting the data. Trustworthiness was created by ensuring that the questions asked of interviewees were closely related to the study's purpose. Data saturation occurred during the first 11 interviews, despite the fact that the fundamental components of the meta themes were already present in the first five interviews. Confirmability was established by using actual quotes to convey the opinions of participants. Individual member checking was done through one-on-one conversation verbally throughout the interviews. Techniques such as paraphrasing and summarisation were used to clarify participants' answers. An email was then sent after the interviews were transcribed, asking for feedback on themes from the participants.

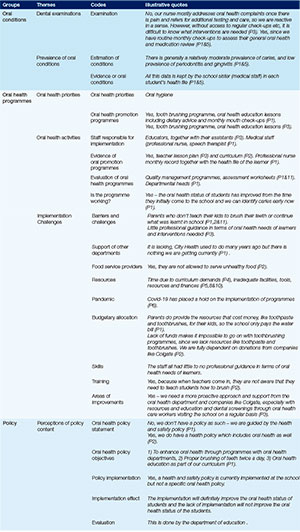

RESULTS

Based on the three groups of interview questions, six themes were developed from the data. The first group focused on oral health programmes, which included three themes: (1) oral health priorities, (2) oral health activities, (3) implementation and evaluation process. These themes highlighted the current oral health programmes offered by special schools as part of oral health education and promotion, by describing the contributions and challenges encountered by schools when raising health awareness to prevent oral conditions and assisting learners in developing oral health care skills, as it involves parents, educators, health workers and the health department. The second group focused on oral health policy, with one theme -perceptions of policy content. This theme analysed policy contributions in oral health, based on the existing oral health policy, policy implementation and policy evaluation. The final group was the oral conditions, which included two themes - dental examinations and prevalence of oral conditions, which highlighted the current state of oral health conditions among learners with special needs attending special schools in KZN.

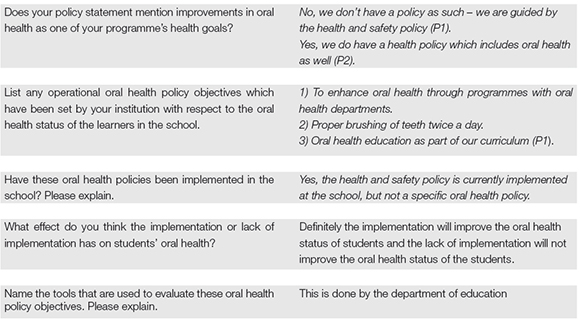

ORAL HEALTH PROGRAMMES

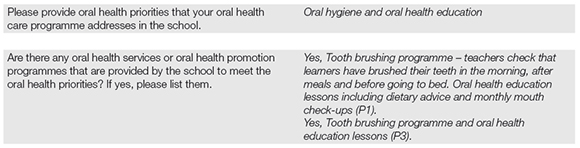

Theme 1: Oral health priorities

Many interviewees stated that oral hygiene was a priority in their schools. This was addressed in a variety of ways by educators' efforts to promote learners' oral health, including: providing oral health education and dietary advice in the health education lesson or life skills lesson, supervised tooth brushing programme, in which educators frequently check that learners have brushed their teeth in the morning, after meals and before going to bed for those who are boarding. Pain management and oral examination was only offered by a few schools

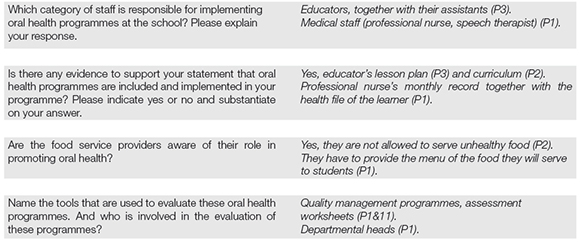

Theme 2: Oral health activities

The implementation of actual oral health activities was carried out by the educators and educators' assistants in the classrooms with the help of school nurses, although not all schools had nurses. They gave information on the causes and prevention of oral diseases as well as skills training to prepare learners to practise good oral hygiene care. To discourage learners from developing eating habits that lead to oral disorders, they also offered information about the side effects of oral diseases, such as pain and cavities. The evidence to support this was the educators' lesson plan and curriculum. Food service providers were also not permitted to serve unhealthy food as they are required to present a menu of the food that they serve. Quality management programmes with the use of assessment worksheets were the tools used by the departmental heads to evaluate the oral health care programmes.

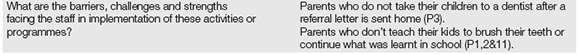

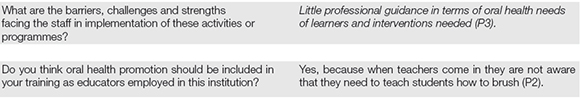

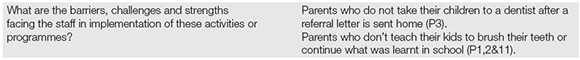

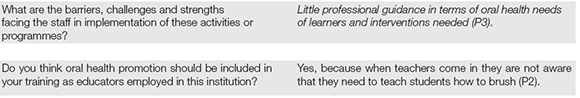

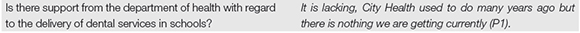

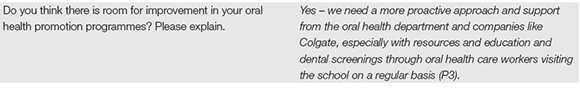

Theme 3: Implementation challenges

The implementation of the programme was impacted by five factors: lack of parental support, lack of professional guidance, lack of educators' training, lack of resources and lack of support from the oral health department. The Covid-19 pandemic further exacerbated these challenges. These factors influenced the programme's implementation in various ways, either directly or indirectly.

Parents were key actors when it came to learners referred for further treatment. However, the principals mentioned a potential disadvantage of this open method is that some parents are hesitant to take their children to oral health care facilities for treatment. Some parents did not even teach their kids to brush their teeth at home or continue what was learnt in school.

The participants reported a lack of professional guidance and teacher training in terms of oral health needs and interventions needed.

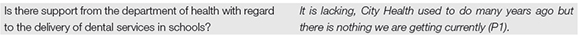

The participants reported a lack of support from the oral health department and non-government oral health organisations such as Colgate, who used to visit schools with mobile clinics and provide oral health education, dental examinations and, occasionally, treatment. This usually helped teachers because they knew where to refer students and who to ask for professional guidance.

Some of the most important details in this theme were the lack of time, resources and finances for oral health and promotion in the schools. There is not enough time spent on oral health and promotion because there are curriculum demands and school syllabuses that must be completed within a certain time frame. Parents do provide the necessary resources that cost money, such as toothbrushes and toothpaste. However, many schools lack funds, making it impossible for them to continue with some of their oral health programmes. This paucity of resources was brought on by the fact that oral health is not included in the school's healthcare budget, resulting in schools being fully dependent on companies such as Colgate to donate toothpaste, toothbrushes and educational charts.

The participants reported a lack of professional guidance and teacher training in terms of oral health needs and interventions needed.

The participants reported a lack of support from the oral health department and non-government oral health organisations such as Colgate, who used to visit schools with mobile clinics and provide oral health education, dental examinations and, occasionally, treatment. This usually helped teachers because they knew where to refer students and who to ask for professional guidance.

The Covid-19 pandemic has changed the way teachers contribute to oral health promotion activities in schools, limiting interactions between children, educators and the community. These measures include limiting the number of oral health education sessions, school days and health assessments, and restricting other healthcare stakeholders from accessing school premises.

Despite the fact that students' oral health has improved since they first enrolled in the schools, these implementation challenges reveal a clear need for adjustments in several areas. To enhance the oral health status of students, a more proactive strategy with complete stakeholder engagement is required, as alluded to by the interviewers.

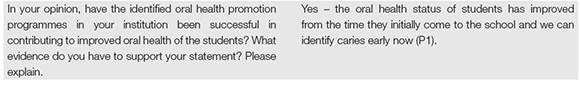

POLICY

Theme 4: Perceptions of policy content

Interviewees agreed that schools don't have a separate oral health policy, but rather it is integrated into other health policies. The improvement of oral health through programmes with oral health departments, appropriate tooth brushing twice daily and oral health education as part of the school curriculum were among the main oral health policy objectives that were highlighted. These existing policies are currently implemented and have improved the oral health status of students, while the lack of implementation will deteriorate the oral health status of the learners. The department of education evaluates these policies and no tools were specified.

ORAL HEALTH CONDITIONS

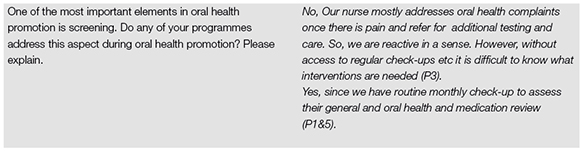

Theme 5: Dental examinations

The majority of interviewees stated that no oral examinations were conducted in their schools; rather, a student's complaint would prompt a check-up and referral to an outside public health facility for oral health investigation, diagnosis and treatment. Some interviewees, however, stated that their schools were active in the assessment, management and monitoring of learners' health. The school nurse would conduct routine health inspections once a month in the nurse's room. During these health inspections, the nurse performs a visual inspection of the learners, including their mouths, and also checks the medication of those learners who receive treatment while at school. When concerns with a learner's dental health were discovered, the nurse made the decision to supply a form of management at school or refer them to an oral health institution. At school, the most prevalent therapy was basic pain alleviation with medicine. Nurses referred more complex cases to local oral health clinics by writing the condition in the communication book or calling the parents to inform them. Plans for continued care of oral issues have been informed through the health inspections, including alerting parents of their children's oral health status and providing guidance to learners on basic oral hygiene.

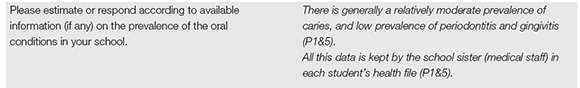

Theme 6: Prevalence of oral conditions

Interviewers from schools that provide oral examinations agreed there was generally low to moderate dental caries prevalence and low prevalence of periodontitis, gingivitis and oral lesions. Medical records of learners kept by the schools were the only epidemiological evidence available to corroborate the prevalence of oral diseases at the schools.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed that certain critical components of health-promoting schools (HPS) were in place, such as school health education, a healthy school environment, a social environment, community relationships, nutrition and food services.3 Leaving out one of the key components of the HPS; the school health services, since oral health services were not necessarily provided on the school premises, revealing a gap in unmet treatment needs. This is similar to what is reported in the Integrated School Health Programme (ISHP) which states that the health services package for the ISHP includes a significant component of health education for each of the four school phases, health screening (such as screening for vision, hearing, oral health and TB) and onsite services such as deworming and immunisation.20 This leaves out the provision of oral services and the only exception is documented on the integrated school oral health policy where oral health services are stated to be provided in the foundation phase (when available).5 Each of these components provides numerous opportunities to address oral health concerns and it is critical that these initiatives are supported by school health policies21, 22 As the study participants stated, schools do not have a separate oral health policy; rather, it is integrated into other school health policies that are implemented. This is consistent with the results of a study conducted on health-promoting schools which state that a policy can be established to handle a particular issue, but it may be advantageous to address multiple risk factors in a single policy.3

This study found that each school was in charge of facilitating oral health care programmes, as it was stated that oral hygiene was prioritised in schools and addressed through providing oral health education, dietary advice and supervised tooth brushing programmes in the health education lesson or life skills lesson, as skills training to prepare learners to practice good oral hygiene care, reducing oral condition and improve oral health status. These results are similar to that of a systematic review on the effectiveness of oral health education programmes which revealed that oral health education programmes are given in the form of instructions, demonstration of oral hygiene practices, group discussions and lectures.23 The school principals further stated that educators were the people responsible for implementing the oral health programme, which is consistent with the results of a study conducted in Bhopal, India, where educators were suggested and made responsible for the implementation of oral health programmes.24

These schools' oral health programmes were geared more toward a preventive care approach rather than a therapeutic or curative care approach. The majority of interviewees stated that no oral examinations were conducted in their schools; rather, a student's complaint would prompt a check-up, pain management and a referral to an outside public health facility for oral health investigation, diagnosis and treatment. This is contrary to what was specified in the Integrated School Health Policy which emphasises providing health services over screening and referral in schools, with a commitment to expanding services over time, including mechanisms for ensuring additional services are provided for learners assessed as needing them.5 Furthermore, other studies on the effectiveness of oral health education programmes revealed that they include preventive and therapeutic interventions in addition to oral health education.23

The implementation of school-based oral health promotion programmes in this study has been impacted by factors such as lack of parental support, professional guidance, teacher training, resources and support from the oral health department. The Covid-19 pandemic has further exacerbated these challenges. This is consistent with the Integrated School Health Policy, which identifies the suboptimal provision of school health services due to factors such as insufficient collaboration between the Department of Health and Education (DOH) and Department of Education (DBE), inequitable resource distribution, competition for limited resources, the demand for curative services over preventive and promotive services and poor data management, which also impacts reporting of school health services.5 Furthermore, in Tshwane, South Africa, research revealed a mismatch between policy and practice, with poor prior planning, insufficient funding, poor school facilities and a lack of cooperation from key stakeholders.7

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

The current study provided a good understanding of oral health care service delivery in special needs schools in eThekwini District, KZN. However, several limitations were noted: the study participants were facilitators of the oral health programmes rather than actual implementers of the oral health programmes within the schools. As a result, their responses to questions could have been skewed toward the ideal answers (social desirability) rather than what is actually happening on the ground. Thus, there could have been overreporting of the execution of oral health programmes at the identified schools. Another reason could be that the participants were not health professionals and could have a limited understanding of the actual running of the oral health programmes, resulting in limited responses. There was a lack of current and clear publicly available records of the oral health programmes' evaluation and therefore the need to strengthen the monitoring and evaluation systems by the schools and the departments. Future research is required to compare the schools' manager's statements with the educators, school nurses and oral healthcare providers' perspectives about the current state of oral health care delivery in special schools so as to improve the sample's representativeness and gain input from the people in the implementation levels.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To improve school oral health services and programmes, there should be an increased number of school health nurses and staff training for sustainable oral health strategies there. Each special school should have at least one school health nurse employed so as to help with the facilitation and implementation of oral health care programmes and services.5 Educators and school nurses should be trained to inspect learners' mouths periodically to facilitate early detection of anomalies or changes in oral health status.25 Parents should be informed about the consequences of not attending to or treating their children's oral health needs and positive reinforcement should be used to acknowledge improvements in learners' oral hygiene practices.26 Educators should be encouraged and supported to implement oral health interventions with or without school health nurses and oral health personnel. Furthermore, educators should receive continuous oral health promotion training to carry out oral health promotion programmes.3,27 Oral health education should also be integrated into the curriculum of teacher training programmes, which require negotiations with South African educator training institutions.28

Educators should collaborate with dental professionals to promote oral health concepts and hygienic skills in learners, thus increasing their own knowledge and skills for effective oral health promotion programmes.26 Schools should include close associations between educators, parents and dental professionals to increase parents' knowledge and skills, minimise learners' dental caries risk and reduce parental resistance to oral health activities.29 Public oral health or dental facilities should be strengthened to supervise preventive dental education and provide services such as oral health screening, fissure sealant placement, fluoride varnish treatments and Atraumatic Restorative Technique on school premises.7 Collaboration between the DOH and DBE is needed to resolve and improve many problems encountered by educators during the implementation of oral health programmes in these special schools.17

CONCLUSION

It was evident in the current study that special schools do have oral health programmes in place which are mostly preventative and promotive in nature. However, this highlighted the need for therapeutic or curative services to cater for unmet treatment needs of the learners. Furthermore, gaps in the implementation of the oral health programmes were impacted by a number of factors. Together, these findings point to the urgent need to review oral healthcare programmes for learners in special schools in KwaZulu-Natal. This review should ensure proper support and collaboration between the key stakeholders and special schools to reduce negative effects and improve the overall oral health programmes within the schools.

REFERENCES

1. Nqcobo C, Ralephenya T, Kolisa YM, Esan T, Yengopal V. Caregivers' perceptions of the oral- health-related quality of life of children with special needs in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Interdiscip Heal Sci. 2019;24 [ Links ]

2. South Africa, Doh. National_Policy_Oral_Health_Sa.Pdf. 2003 [ Links ]

3. Kwan SYL, Petersen PE, Pine CM, Borutta A. Health-promoting schools: an opportunity for oral health promotion. Bull World Heal Organ. 2005;83(9):677-85 [ Links ]

4. National Department of Health South African. National Oral Health Strategy. Pretoria: DoH 2010 [ Links ]

5. Department of Health and Basic Education. Integrated school health policy. 2012 p. 140-4 [ Links ]

6. South African National Department of Health. National school health policy and implementation guidel ines. Cluster: Maternal child and women's health and nutrition. 2002. p. 1-37 [ Links ]

7. Molete M, Stewart A, Bosire E, Igumbor J. The policy implementation gap of school oral health programmes in Tshwane, South Africa: A qualitative case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1-11 [ Links ]

8. Altun C, Guven G, Akgun OM, Akkurt MD, Basak F, Akbulut E. Oral Health Status of Disabled Individuals Attending Special Schools. Eur J Dent. 2010;04(04):361-6 [ Links ]

9. Vinereanu A, Munteanu A, StBnculescu A, FarcaSu AT, Didilescu AC. Ecological Study on the Oral Health of Romanian Intellectually Challenged Athletes. Healthc. 2022;10(1):1-9 [ Links ]

10. Wilson N, Lin Z, Villarosa A, George A. Oral health status and reported oral health problems in people with intellectual disability: A literature review. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2019;44(3):292-304 [ Links ]

11. Akinwonmi B, Adekoya-Sofowora C. Oral health characteristics of children and teenagers with special health care needs in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. African J Oral Heal. 2019;8(2):13 [ Links ]

12. Nqcobo C, Yengopal V, Rudolph M, Thekiso M, Joosab Z. Dental caries prevalence in children attending special needs schools in Johannesburg, Gauteng Province, South Africa. SADJ. 2012;67(7):308-13 [ Links ]

13. World Health Organization. Oral health. World Health Organization. 2020 [ Links ]

14. Oredugba FA, Akindayomi Y. Oral health status and treatment needs of children and young adults attending a day centre for individuals with special health care needs. BMC Oral Health. 2008;8(1):1-8 [ Links ]

15. Naseem M. Oral health knowledge and attitude among caregivers of special needs patients at a Comprehensive Rehabilitation Centre: An Analytical Study. Ann Stomatol (Roma). 2017;8(3):110 [ Links ]

16. Bennet Y. List of special needs schools (SPED schools) in South Africa [Internet]. Briefly. 2021. Available from: https://briefly.co.za/86113-list-special-schools-sped-schools-south-africa.htmlle [ Links ]

17. Reddy M, Singh S. The promotion of oral health in health-promoting schools in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. SAJCH South African J Child Heal. 2017;11(1):16-20 [ Links ]

18. Nemutanda M, Adedoja D, Nevhuhlwi D. Dental caries among disabled individuals attending special schools in Vhembe district, South Africa : research. SADJ. 2013;68(10) [ Links ]

19. Ningrum V Wang WC, Liao HE, Bakar A, Shih YH. A special needs dentistry study of institutionalized individuals with intellectual disability in West Sumatra Indonesia. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1-8 [ Links ]

20. Department of Basic Education, Department of Health, Department of Social Development. Integrated School Health Programme (ISHP). 2013 [ Links ]

21. World Health Organization. WHO Information Series on School Health. Educ Dev Center, Inc. 2003;1-65 [ Links ]

22. World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Regional guidelines : development of health-promoting schools - a framework for action. 1996; (Development of health-promoting schools - A framework for action):26 [ Links ]

23. Nakre PD, Harikiran A. Effectiveness of oral health education programs: A systematic review. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2013 [ Links ]

24. Sharma A, Reddy V, Jain S, Bansal V, Niranjan B. Perception of Teachers about Implementation of Oral Health Education in Primary School Curriculum. Int J Dent Med Spec. 2016;3(4):10 [ Links ]

25. Myburgh N, Hobdell M, Lalloo R. African countries propose a regional oral health strategy: The Dakar Report from 1998. Oral Dis. 2004;10(3):129-37 [ Links ]

26. Sowmiya Sree RA, Joe Louis C, Senthil Eagappan AR, Srinivasan D, Natarajan D, Dhanalakshmi V. Effectiveness of Parental Participation in a Dental Health Program on the Oral Health Status of 8-10-year-old School Children. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2022;15(4):417-21 [ Links ]

27. Wierzbicka M, Petersen P, Szatko F, Dybizbanska E, Kalo I. Changing oral health status and oral health behaviour profile of schoolchildren in Poland. Community Dent Heal. 2002;19(4):243-50 [ Links ]

28. Haque S, Rahman M, Itsuko M, Kayako S, Tsutsumi A, Islam M, et al. Effect of a school-based oral health education in preventing untreated dental caries and increasing knowledge, attitude and practices among adolescents in Bangladesh. EMC Oral Heal. 2016;(16):44 [ Links ]

29. Gargano L, Mason MK, Northridge ME. Advancing Oral Health Equity Through School- Based Oral Health Programs: An Ecological Model and Review. Front Public Heal. 2019;7(November):1-9 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Name: S Gumede

Email: Sinenhlanhla.gumede41@gmail.com

Author's contribution

1 . S Gumede - study conceptualisation, data analysis, manuscript preparation, writing and final editing (60%)

2 . S Singh - data analysis, manuscript preparation and editing (20%)

3 . M Radebe - data analysis, manuscript preparation and editing (20%)

Acknowledgments

None

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.