Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Dental Journal

versión On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versión impresa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.78 no.7 Johannesburg ago. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sadj.v78i07.17072

RESEARCH

Dental therapist job satisfaction and intention to leave: A cross-sectional study

P SodoI; V YengopalII; S NemutandaniIII; T MuslimIV; S JewettV

IBDT, Advanced Diploma in Comm Dent, MPH, PhD Candidate, School of Clinical Medicine, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2542-6038

IIBChD, BSc Hons, MChD, PhD (Dental Public Health), Faculty of Dentistry, University of Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4284-3367

IIIB ChD, MPH, M Sc-Med, M ChD, PhD Public Health, Research and Innovation Directorate, Sefako Makgatho Healt Sciences University, Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7335-4414

IVBDT, Doctor of Philosophy in Health Sciences Degree, Discipline of Dentistry, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5824-6191

VPhD, School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg, South Africa. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6658-2061

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Dental therapy is a mid-level oral health profession that was introduced to the South African health system more than four decades ago, during the apartheid era. The purpose for the introduction of this profession was to meet the oral health needs of the underserved majority population1,2,3. However, even with the dismantling of apartheid and the creation of a democratic state, disparities in access to basic oral healthcare persist.1 Local studies have reported limited access to oral health services, especially among the disadvantaged and vulnerable population groups where the highest burden of oral diseases has been reported.4,5,6

The scope of dental therapists includes treating and preventing the most prevalent oral health problems in South Africa, such as dental caries.1,2,4,5,6 Globally, dental therapists play a significant role in providing basic dental services at a low cost compared to dentists, especially to children and underserved communities.7 One strategy for reducing health disparities is to lower the unit cost of providing services by substituting higher-cost labour associated with hiring dentists with low-cost labour, such as dental therapists.7 The dental therapy profession is not a replacement for dentists; however, it is an economically sustainable professional mid-level workforce category where you can employ up to three dental therapists with the salary of one dentist.7 Despite the need for this professional group, anecdotal data reveals that fewer dental therapists are being trained compared to dentists. Furthermore, there is imminent attrition among dental therapists which threatens the profession and limits the benefits conferred by this category of workers.

Attrition among dental therapists is a threat to the potential benefits of this category of worker. A study conducted among dental therapists in Western Australia reported that 28% of dental therapists were no longer working within the profession due to new careers, family commitments, relocation, poor pay, injury or stress.8 In South Africa, although dental therapists are trained and produced every year from the Sefako Makgatho University (SMU) and the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), the numbers of graduate dental therapists registered with the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) remain low.9 A regional study in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) reported a high voluntary attrition among dental therapists10. The study reported that 26% of dental therapists left the profession, of whom 19% returned to university to study dentistry while 7% no longer work in the dental profession. A more recent South African nationwide study of dental therapist attrition reported 40% attrition over a 42-year period and attrition of 9% over the 10-year period of 2009-2019.11

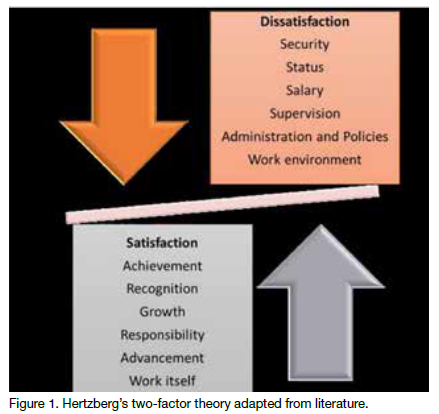

Voluntary workforce attrition is a major public health problem globally, which may lead to staff shortages. Some of the downstream effects of voluntary attrition are increased workload, unavailability of healthcare workers and limited access to healthcare, leading to a higher burden of untreated diseases. Furthermore, this has a huge impact on a country's economy.12 Voluntary attrition has been identified as an essential issue that needs to be addressed for workforce planning.12 There are many reasons why a person might voluntarily leave their job. Previous studies have cited low salaries, lack of access to professional development and further education, lack of effective supervision, weak regulatory environments, isolation for those in rural or remote areas, poor working conditions, large workload, lack of motivation and low job satisfaction as major contributors to voluntary attrition.12,13,14,15,16,17,18 Furthermore, studies conducted among mid-level health workers reported that these cadres leave because they are becoming demotivated due to poor career development and promotion prospects, lack of positive supervision, feedback and recognition, which leaves them feeling unsupported and undervalued as professionals.14,19,20,21,22 One study conducted among anaesthetists reported that 47.8% of participants had the intention to leave their profession due to low remuneration and lack of opportunities for professional development.23 Factors contributing to job dissatisfaction and, ultimately, attrition, can be conceptualised using Hertzberg's two-factor theory (see Figure 1). According to this theory, intrinsic factors (motivators) such as recognition, achievement, work itself, responsibility and advancement will all lead to job satisfaction; whereas factors that lead to job dissatisfaction include the absence of key extrinsic factors (hygiene factors) such as policies and administration, supervisory practices, salary, interpersonal relations, physical working conditions, benefits and job security24,25 Hertzberg's two-factor theory describes intrinsic factors as motivators that contribute to job satisfaction and extrinsic factors as major contributors to dissatisfaction, If absent.24,25

A study conducted among different categories of healthcare workers In three countries, including South Africa, reported an association between low job satisfaction and Intention to leave18 among the three countries (Tanzania, Malawi and South Africa). The lowest job satisfaction and the highest Intention to leave were in South Africa, where 47.9% of those surveyed were dissatisfied with their current jobs and 41.4% were actively seeking other jobs.18 Other studies also have reported the Intention to leave as the strongest predictor of voluntary workforce attrition.12,14

Documenting the factors that contribute to job dissatisfaction, intention to leave and attrition Is essential for human resource planning and the development of strategies to reduce voluntary attrition. There Is limited Information on factors contributing to attrition or an Intention to leave the dental therapy profession In South Africa. Hence, the purpose of this study was to investigate factors that Impact on job dissatisfaction and the intention to leave the dental therapy profession.

METHODOLOGY

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted among dental therapy graduates using an electronic survey Instrument called Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).

Study population

The targeted study population included all the graduate dental therapists.

Recruitment of participants

Participants were recruited thought the online platforms of the South African Dental Therapy Association (SADTA), which had a membership of 200 dental therapy graduates at the time of data collection. The SADTA platforms used for recruitment included emails and WhatsApp groups. The survey link generated by REDCap was shared through these platforms; participants were also encouraged to forward the link to other dental therapists who were not members of SADTA. The calculated minimum sample size for this study was 198 based on the total number of dental therapists registered by 2019 (714), using a 90% confidence Interval and 5% marginal error.26

DATA COLLECTION

Data collection instrument

The study used a self-administered questionnaire that was adapted and modified from existing previously validated studies20,21,27, some of which used the constructs of Hertzberg's Two-Factor Theory of Motivation. These previous studies captured the predictors of job satisfaction and intention to leave the profession as well as factors contributing to attrition. The questionnaire for our study captured demographics, Individual factors, extrinsic factors and intrinsic factors as well as job satisfaction and Intention to leave. The Intention to leave the dental therapy profession and job satisfaction were the outcome variables of Interest. Job satisfaction was explored as a binary variable (yes/no), as Hertzberg's two-factor theory Identified It as the major factor In the decision to quit or stay in a job or profession.25 Measurement of variables

The questionnaire requested Information on sociodemographic characteristics, Including age, gender, race, province of residence, highest degree, year of qualification, Institution where participants qualified, employment sector and their year of qualification.

Two additional questions were measured through binary (yes/no) variables: whether dental therapy was the study participants' first choice and If the participants were funded for their dental therapy degree.

Five questions were related to intrinsic variables. These Included four binary (yes/no) variables, Including the awareness of available postgraduate prospects for dental therapists, whether the dental therapy profession received professional growth, satisfaction with the current dental therapy scope of practice, and one nominal variable such as the stage at which participants became aware of dental therapy scope of practice. Three questions probed extrinsic variables, of which two required binary (yes/no) responses. These Included the availability of job opportunities and whether participants felt that the dental therapy profession was valued like other mid-level health professionals in South Africa, and one numerical variable which included the period that It took for the participants to get a job after graduation. The questionnaire also included an open-ended question to gain insight Into participants' reasons behind their dissatisfaction with the dental therapy profession, using their own words. Data were collected between April 2020 and March 2022.

Participation was voluntary and informed consent was obtained electronically from all the participants. The survey link had the information sheet for participants to read and understand the purpose of the study and conditions of their participation which included anonymity and that participation was voluntary; thereafter there was a consent statement Informing participants that "by proceeding to complete the survey, they consent to participate in the study".

Data management andanalysis

The first author transferred data from REDCap into Excel for cleaning and then transferred the clean dataset to STATA 15, LP, College Station, TX, US, for analysis. Missing cases were excluded from the analysis. Overall, 234 participants participated in the study, of which 34 responses were excluded because they had many missing responses, leaving us with 200 responses.

Descriptive statistics were done to describe the study sample in terms of socio-demography and key participant characteristics; this included frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, while means and standard deviations were computed for continuous variables. Job satisfaction and intention to leave were also determined using descriptive statistics. Associations between either job satisfaction or intention to leave and participant's characteristics were explored using bivariate analysis. All characteristics that were significant (below 0.05) were included in the multivariable logistic regression. We reported adjusted odds ratios, their corresponding 95% confidence intervals and p values. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the open-ended questions, following the process detailed by Braun28 through gaining familiarity with the data; generating initial codes or labels; searching for themes or main ideas; reviewing themes or main ideas; defining and naming themes or main ideas; and producing the report. The first author led this analysis, with support from the last author at the stage of reviewing and defining themes.

RESULTS

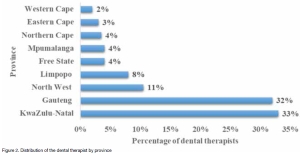

The responses of 200 dental therapist graduates were included in the final analysis. Figure 2 below shows that most participants resided in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng (33.0% and 32.0% respectively).

Table 1 shows that the average age of the participants was 38 years. The sample was dominated by females (62.0%), those who self-identified as African (74.5%) and those employed in the private sector (67.9%). Only 24.6% had a postgraduate qualification. When asked about the circumstances of entering the profession, more than half (52.5%). reported that dental therapy was not their first choice at the time of enrolment, 78.5% were unaware of the dental therapy scope of practice until after enrolment, with 67.5% reporting dissatisfaction with the dental therapy scope. Just above half (53.5%) reported that they had no job opportunities after graduation. The vast majority (90.5%) believed that the dental therapy profession did not support career development and 93.0% indicated that the profession is not valued in South Africa. Job dissatisfaction was high at 69.5%, with more than half (51.5%) expressing their intention to leave the profession.

Job satisfaction among the dental participants

As shown in Table 2, bivariate analysis revealed several factors that were associated with job satisfaction. There was an association between job satisfaction and the institution where participants qualified; those who qualified from SMU were more satisfied with their jobs as compared to UKZN graduates (66.1% vs 33.9%). The majority of those for whom dental therapy was not their first choice in university were more satisfied than those whose first choice was dental therapy (66.7% vs 33.3%). Surprisingly, more than two-thirds (76.7%) of those who were not satisfied with the scope of practice were satisfied with their jobs.

Those who had job opportunities available after graduation were more satisfied with their jobs as compared to those who had no jobs (68.3% vs 31.7%). There was a significant association between awareness of and access to postgraduate opportunities; the majority (67.8%) of those who were aware of postgraduate opportunities were satisfied with their jobs.

In contrast, a large majority (81.8%) of those who only became aware of dental therapy scope of practice after enrolling for the degree were dissatisfied with their jobs. Almost all (97.8%) of those who believed that dental therapists are not as valued as other mid-level health professionals in South Africa were dissatisfied with their jobs.

As shown in Table 3, some factors were no longer significant after adjustment, such as age, dental therapy being their first choice, whether their studies were funded and whether they were satisfied with the dental therapy scope of practice. However, several factors remained significant after adjustment. For instance, there was positive association between job satisfaction and being a graduate of UKZN (AOR=2.28, CI: 1.06-4.91), having job opportunity available after graduation (AOR=3.87, CI: 1.73-8.69), being aware of postgraduate opportunities available for dental therapists (AOR=2.28, CI: 1.05-4.96) and believing that the dental therapy profession is valued like other mid-level health professionals (AOR=6.19, CI: 1.45-26.36). Conversely, job satisfaction was negatively associated with only becoming aware of the dental therapy scope of practice after enrolment (AOR=0.31, CI: 0.12-0.81).

The responses to open-ended questions about job dissatisfaction provided additional insights on what was contributing to their feelings, with the responses corresponding to the quantitative results that emphasised issues such as career opportunities and whether they felt valued. We classified these themes into broad intrinsic and extrinsic factors as stipulated in the Hertzberg framework.

Intrinsic factors

There were three themes related to intrinsic factors: lack of respect, limited responsibility and limited career growth. While these all related to lack of recognition as professionals, which was also significant in the quantitative analysis, the qualitative responses enabled us to explore the reasons underlying their responses.

Participants believed that their role within the health system was not well understood; hence, other health professionals undermined and took advantage of them. A common theme that emerged from their responses was the lack of respect or appreciation afforded to those in the dental therapy profession. This included allusions to the racialised nature of the profession and its historical role in the apartheid government:

Leadership viewed us as second-class dentists, who are also incompetent. Everyone looked down upon us: employers, government, dentists, medics, institutions, including other races (we are mostly black). (Female, 54).

We are seen as robots and slaves and get undermined a lot. The way other professions think of dental therapists and react to them demonstrates a disregard for the profession. The state as the employer sees dental therapists as instruments of cheap labour just as apartheid aimed it to be. (Male, 34).

Participants linked this disrespect to a second theme of being given limited responsibility. For instance, some described being overlooked for management positions or promotion opportunities. Reinforcing the idea of being treated as "second-class" citizens, one female dental therapist (age 28) complained: "We are hardly recognised and given responsibility. Always expected to work under a dentist."

Limited career growth was a third theme that caused great dissatisfaction among dental therapists. They felt that they played a critical role in-service provision, yet they perceived few career growth opportunities, going beyond what the survey measured. One explained:

Options to study further are mainly in public health and when you are done there are no posts that are designed for dental therapists who did MPH (master's in public health), or anything related to that. Even if you do the postgraduate diploma in dental public health, there will be no post for you in government. You are supposed to apply for the ordinary post like any person with an undergraduate degree. (Male, 32).

Extrinsic factors

We identified five themes related to extrinsic factors: limited job opportunities, inequitable remuneration, unfair medical aid practices, government disregard and poor interpersonal relations.

While these all related to job satisfaction, which was also significant in the quantitative analysis, the qualitative responses enabled us to explore the reasons beyond their job satisfaction. The intrinsic sense of frustration about career growth opportunities was reflected in the extrinsic theme of there being limited job opportunities. The following example highlights how the absence of jobs in the public sector has driven some to shift into the private sector, despite the need for dental therapists in the public sector.

[There are] no job opportunities in the public sector and demand for mid-level workers to provide primary healthcare is high. The implementation of NHI (National Health Insurance) will need the mid-level worker to strengthen oral health promotion and prevention in the integrated school health programme. Because no one, not even our own government, and the Department of Health has space for us. We are trained so that post-graduation we fend for ourselves in the private sector, which predisposes us to be underpaid and overworked. (Female, 51).

Recently I checked the OSD (Occupational Service Dispensation) scale only to learn that oral hygiene entry-level post pays a lot more than a dental therapy post. Salary levels and other benefits are not aligned with other health professionals in public institutions. The question is what informs the salary scale of professions if not the scope of practice? (Male, 30).

A closely related theme had a narrow focus on the practices of unfair medical aid schemes, which focused on how participants believed that medical aid schemes are unfair to dental therapists in terms of remuneration. In one case, a study participant left the profession as a consequence:

I felt abused by the system with less remuneration in all aspects, at both public and private sectors. In government, it was worse. The unregulated medical aid schemes were also not remunerating us according to the work done, but less or no payments due to the fact that we are therapists. I felt that we were not protected by anyone against this abuse. I had to leave the profession. (Female, 54).

Some of the complaints about medical aid structures were very specific:

Medical aids dictate what should be done by therapists, for example you can't treat more than 4 teeth in a year while patients might require more. These limitations are not there for other professionals. (Female, 30).

Participants felt the dental therapy profession was disregarded by the government. Two examples were mentioned by participants who believed that dental therapists were excluded from policies such commuted overtime and community service, where other health professionals were included:

The government refuses to give us community service programmes immediately after graduation in the public sector but instead provides it to other professions. We are thus not recognised and not taken seriously. (Male, 23).

Finally, intricately linked to the intrinsic theme of lack of respect, some participants also reported poor interpersonal relations. One female dental therapist (age 30) lamented: "There is hatred and discrimination against the dental therapy profession everywhere, from dentists, management, medical aid administrators etc." Other dental therapists used words like "discrimination" and "oppression" to describe the way they were treated. As one explained, this type of treatment also affected their relationship with patients:

We are taken for granted and there is so much oppression. We are also believed to not know or carry out our scope of practice with excellence that leads to patients not trusting us. (Female, 31).

Intention to leave among the dental participants

Table 4 shows the bivariate analysis of intention to leave and its correlates. There was a significant association between intention to leave and age, race, funding for dental therapy degree, highest qualification, year of qualification and job satisfaction. More younger participants had the intention to leave their jobs than the older participants. Those participants who identified as African race reported high intention to leave (83.5%). High intention to leave was reported among those participants who were funded for their dental therapy degree (63.1%). More than two-thirds (81.4%) of participants who did not have postgraduate qualification. High intention to leave was reported among those participants who qualified between the years 2000-2009 and between 2010-2019 (43.1% and 41.2% respectively). The majority (82.2%) of participants who were dissatisfied with their jobs reported an intention to leave. Finally, although not significant, high intention to leave was reported among the majority of participants who reported that the dental therapy profession was not valued in South Africa (96.1%).

Predictors of the intention to leave

As shown in Table 5 some factors were no longer significant after adjustment, such as having dental therapy as first choice of study, being funded for dental therapy degree, highest degree obtained, year of qualification, awareness of dental therapy scope of practice, and reporting that dental therapy profession is valued in South Africa. However, other factors remained significant after adjustment. For instance, the intention to leave was negatively associated with older individuals (AOR=0.93, CI: 0.86-0.99); those who identify as Indian race group (AOR=0.30, 95% CI: 0.13-0.72) and those who have job satisfaction (AOR=0.25, CI: 0.21-4.16).

DISCUSSION

The study explored job satisfaction and intention to leave among South African dental therapists. Only 30.5% of the participants reported being satisfied with their jobs, while 51.5% expressed their intention to leave the profession, with a significant association between job disatisfaction and the intention to leave. This aligns with Hertzberg's two-factor theory and implies that if employers prioritise job satisfaction, they will reduce attrition.

Our study sample was dominated by African race (74.5%), which is consistent with two other studies of dental therapists in South Africa.10,29 This is aligned with the South African racial profile, where 81% of citizens are Africans30 and also, in part, explained by the fact that dental therapists in South Africa were and are still trained at only two historically black universities.

This study sample predominantly resided in KZN and Gauteng, which are the only provinces where dental therapy training is provided. A recent review of HCPSA records also reported an unequal distribution of dental therapists across South African provinces, with most located in KZN (44%) and Gauteng (27%).11 To ensure equitable distribution of dental therapists throughout the country, training offerings should either be expanded to other provinces or existing programmes should consider more targeted recruitment of future students to be more reflective of underserved provinces.

The majority of study participants worked in the private sector, similar to a previous study on UKZN dental therapy graduates where 47% were in private practice.10 This trend is also seen among dentists, with 70%-80% working in the private sector, which serves about 20% of South Africa's population.31 This concentration in the private sector is partly due to limited job opportunities in the public sector.10 To address dissatisfaction among public sector dental therapists, government should focus on reviewing and properly implementing policies related to recruitment, retention and remuneration in order to attract and retain more dental therapists within the public sector that is utilised by more than 80% of South African citizens.4

The majority of participants in our study expressed job dissatisfaction. Factors influencing job dissatisfaction included the institution where participants qualified, availability of job opportunities, awareness of scope and not feeling valued. These findings align with similar studies conducted in South Africa, the UK and New Zealand.32,33,34 However, these sources of dissatisfaction are not universal among dental therapists. For instance, Australian dental therapists reported satisfaction with the work itself, supportive environment, career development, autonomy and professional recognition.8 Closer to home, a study in West Ethiopia found that more recognition for outstanding performance correlated with higher job satisfaction.34,35 These findings are consistent with Hertzberg's two-factor theory36 and point the the value of addressing perceptions of "lack of respect" and "poor recognition" as strategies for retaining experienced healthcare professionals.

Lack of career pathing was a significant factor contributing to job dissatisfaction among our participants and has been linked to job dissatisfaction and intention to leave in previous studies.8,12 The University of Rwanda provides an example of where this concern has been addressed through the introduction of honours and master's programmes in dental therapy, which have expanded the scope of practice and resulted in no reported attrition in the country.37 South African universities, together with HPCSA, should explore if similar postgraduate programmes could be introduced to expand the scope of practice for dental therapists, aiming to attract and retain more professionals in the field.

Availability of job opportunities post-graduation was associated with high job satisfaction in our study. Perceptions of job opportunities could be improved by offering dental therapists community service jobs immediately after graduation, like other professionals.38 Additionally, community service helps to enhance their skills post-graduation.38 It is crucial for the government to include dental therapists in community service to improve coverage and address the burden of untreated oral diseases.4

Poor remuneration was a significant factor contributing to job dissatisfaction across private, public and academic sectors. Similar studies among dental therapists in South Africa have reported similar frustrations with remuneration,20,21 which has been cited as a top reason for attrition across other professions.39 This calls for improvement of dental therapy salaries and financial benefits for those employed in both the public and academic sectors, this includes salaries (for those employed in the public, academic and private sectors) and retention incentives for those employed in the public sector. Regarding low reimbursement fees by medical aids, dental therapists are allowed to charge what they believe their service is worth; however, the cost should be reasonable and the patient must agree to the cost prior to treatment.

This study has limitations, including potential selection bias due to the nonrepresentative sample of 200 participants, which limits generalisability of the findings. Also, intention to leave a profession is not the same as having already left. However, a strength of the study is the inclusion of qualitative responses that provide additional insight into participants' answers. Future research should employ a qualitative approach to gather more in-depth information on factors contributing to attrition, particularly from dental therapists who have left the profession.

CONCLUSION

Job dissatisfaction and intention to leave among dental therapists in South Africa is prevalent. If study participants act on their intention to leave, the resources invested in their training will have been wasted and communities will continue to be underserved. The intrinsic and extrinsic factors that contributed to job dissatisfaction in this study also point to possible solutions. Managers, universities, policymakers, decision-makers, regulators and medical aid administrators can address these issues by implementing strategies to recruit and retain dental therapists in South Africa. Addressing modifiable factors is crucial for human resources planning, to retain dental therapists within the profession. Of priority is the need to review and revise policies around recruitment and retention, career pathing and remuneration in the private, academic and public sectors. Beyond retention of existing dental therapists, South Africa also needs to act on strategies to expand dental therapy training offerings, with particular attention to proactive recruitment strategies for candidates from underserved parts of the country. In acting on the findings of this study, there is an opportunity to increase access to basic oral health services to underserved populations in South Africa.

REFERENCES

1. Hugo J. Mid-level health workers in South Africa: not an easy option: human resources. South African Health Review. 2005;2005(1):148-58 [ Links ]

2. Lalloo R. A national human resources plan for oral health: is it feasible? South African Dental Journal. 2007;62(8):360-4 [ Links ]

3. Singh PK. The dental therapy curriculum: meeting needs and challenges for oral health care in South Africa. 2011 [ Links ]

4. Van Wyk P, Louw A, Du Plessis J. Caries status and treatment needs in South Africa: report of the 1999-2002 National Children's Oral Health Survey. SADJ: journal of the South African Dental Association = tydskrif van die Suid-Afrikaanse Tandheelkundige Vereniging. 2004;59(6):238, 40-2 [ Links ]

5. Thekiso M, Yengopal V, Nqcobo C. Caries status among children in the West Rand District of Gauteng Province, South Africa, South African Dental Journal, 67 (7) 2012: pp. 318-320. South African Dental Journal. 2013;68(10):477 [ Links ]

6. Joosab Z, Yengopal V Nqcobo C. Caries prevalence among HIV-infected children between four and ten years old at a paediatric virology out-patients ward in Johannesburg, Gauteng Province, South Africa. South African Dental Journal. 2012;67(7):314-7 [ Links ]

7. Bailit HL, Beazoglou TJ, DeVitto J, McGowan T, Myne-Joslin V Impact of dental therapists on productivity and finances: I. Literature review. Journal of Dental Education. 2012;76(8):1061-7 [ Links ]

8. Kruger E, Smith K, Tennant M. Non-working dental therapists: opportunities to ameliorate workforce shortages. Australian Dental Journal. 2007;52(1):22-5 [ Links ]

9. HPCSA. HPCSA annual report. 2018/19 [ Links ]

10. Singh P, Combrinck M. Profile of the dental therapy graduate at the University of KwaZulu-Natal: scientific. South African Dental Journal. 2011;66(10):468-74 [ Links ]

11. Sodo PP, Jewett S, Nemutandani MS, Yengopal V. Attrition of dental therapists in South Africa - A 42-year review. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2022 [ Links ]

12. Lopes SC, Guerra-Arias M, Buchan J, Pozo-Martin F, Nove A. A rapid review of the rate of attrition from the health workforce. Human resources for health. 2017;15(1):1-9 [ Links ]

13. Arati Sudhir Bhokare PDM, Prajakta Ashok Rajput. A Study of Employee Attrition Rate in Hospital Sector. International Journal of Engineering Technology Science and Research. 2017;4(12) [ Links ]

14. Mobley WH. Some unanswered questions in turnover and withdrawal research. Academy of Management Review. 1982;7(1):111-6 [ Links ]

15. Burch V, McKinley D, Van Wyk J, Kiguli-Walube S, Cameron D, Cilliers F, et al. Career intentions of medical students trained in six sub-Saharan African countries. Education for Health. 2011;24(3):614 [ Links ]

16. Al Mamun CA, Hasan MN. Factors affecting employee turnover and sound retention strategies in business organization: A conceptual view. Problems and Perspectives in Management. 2017(15, Iss. 1):63-71 [ Links ]

17. Lok P, Crawford J. The effect of organisational culture and leadership style on job satisfaction and organisational commitment: A cross-national comparison. Journal of Management Development. 2004 [ Links ]

18. Blaauw D, Ditlopo P, Maseko F, Chirwa M, Mwisongo A, Bidwell P, et al. Comparing the job satisfaction and intention to leave of different categories of health workers in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa. Global health action. 2013;6(1):19287 [ Links ]

19. Laminman KD. Attrition in occupational therapy: perceptions and intentions of Manitoba occupational therapists. 2007 [ Links ]

20. Singh PK. Job satisfaction among dental therapists in South Africa. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 2014;74(1):28-33 [ Links ]

21. Gordon NA. Job satisfaction and working practices of South Africa dental therapists and oral hygienists. 2015 [ Links ]

22. Bradley S, McAuliffe E. Mid-level providers in emergency obstetric and newborn health care: factors affecting their performance and retention within the Malawian health system. Human Resources for Health. 2009;7(1):1-8 [ Links ]

23. Kols A, Kibwana S, Molla Y, Ayalew F, Teshome M, van Roosmalen J, et al. Factors predicting Ethiopian anesthetists' intention to leave their job. World Journal of Surgery. 2018;42(5):1262-9 [ Links ]

24. Chiat LC, Panatik SA. Perceptions of employee turnover intention by Herzberg's motivation-hygiene theory: A systematic literature review. Journal of Research in Psychology. 2019;1(2):10-5 [ Links ]

25. Alshmemri M, Shahwan-Akl L, Maude P. Herzberg's two-factor theory. Life Science Journal. 2017;14(5):12-6 [ Links ]

26. Raosoft I. Sample size calculator. Available from: www.raosoft.com/samplesize. 2004 [ Links ]

27. Smerek RE, Peterson M. Examining Herzberg's theory: Improving job satisfaction among non-academic employees at a university. Research in higher education. 2007;48(2):229-50 [ Links ]

28. Braun V, Clarke V Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology. 2006;3(2):77-101 [ Links ]

29. Masetla MM, Mthethwa SR. Dental Therapy Student cohorts: Trends in enrolment and progress at a South African University. South African Dental Journal. 2018;73(6):406-10 [ Links ]

30. Africa DoSS. Mid-year population estimates. STATISTICAL RELEASE. 28 July 2022 [ Links ]

31. McIntyre D. Private sector involvement in funding and providing health services in South Africa: implications for equity and access to health care. EQUINET, Harare: Health Economics Unit. 2010 [ Links ]

32. Carrington SD, Treharne GJ, Moffat SM. Job satisfaction and career prospects of Oral Health Therapists in Aotearoa/New Zealand: A research update and call for further research in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Dental and Oral Health Therapy. 2020 [ Links ]

33. Fernández D, Khareedi R, Rohan M. A survey of the work force experiences and job satisfaction of dental therapists and oral health therapists in New Zealand. ANZ J Dent Oral Health Therapy. 2020;8:23-7 [ Links ]

34. Chen D, Hayes MJ, Holden AC. Investigation into the enablers and barriers of career satisfaction among Australian oral health therapists. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2022 [ Links ]

35. Deriba BK, Sinke SO, Ereso BM, Badacho AS. Health professionals' job satisfaction and associated factors at public health centers in West Ethiopia. Human resources for health. 2017;15(1):1-7 [ Links ]

36. Herzberg F. Motivation to work: Routledge; 2017 [ Links ]

37. Health RMo. PRESIDENTIAL ORDER N°119/01 OF 09/12/2011 MODIFYING AND COMPLEMENTING PRESIDENTIAL ORDER N° 27/01 OF 30/05/2011 DETERMINING THE ORGANIZATION, FUNCTIONING AND MISSION OF THE FINANCIAL INVESTIGATION UNIT. In: Health Mo, editor. Rwanda: Official Gazette; 26/12/2011. p. 35-7 [ Links ]

38. Reid S. Community service for health professionals: human resources. South African Health Review. 2002;2002(1):135-60 [ Links ]

39. Parker K, Horowitz JM. Majority of workers who quit a job in 2021 cite low pay, no opportunities for advancement, feeling disrespected. Pew Research Center. 2022 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

P Sodo

pumla.sodo@wits.ac.za

Author's contribution

1. Pumla Sodo 50%

2. Veerasamy Yengopal 15%

3. Simon Nemutandani 10%

4. Tufayl Muslim 10%

5. Sara Jewett 15%