Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562

Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.78 n.3 Johannesburg Apr. 2023

RESEARCH

Hard tissue characteristics of patients with bimaxillary protrusion

MI OsmanI; MPS SethusaII

IMDent Registrar (2021) Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, BDS (University of Limpopo). ORCID: 0000-0003-4081-8870

IIHead of Department of Orthodontics Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, B (Diag) Rad and BDS (Medunsa), PDD (Stellenbosch), MDent Orthodontics (University of Limpopo), P G Dip (UCT). ORCID: 000-002-0884-3008

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Bimaxillary protrusion (BP) is a common developmental condition amongst the South African Black population characterized by proclined incisors with resultant procumbency of the lips

AIMS: The aim of this study was to perform a cephalometric radiographic analysis of the pre-treatment dental and skeletal structures in a sample of Black South Africans in order to identify the characteristic features of BP in this race group and compare them to norms

MATERIALS AND METHODS: Records of 67 South African Black patients divided into 28 males and 39 females with a mean age of 17.8 years, clinically diagnosed with BP were included in the study. Cephalometric parameters were hand traced on lateral cephalometric radiographs and measurements recorded for evaluation and comparison to norm values used for this population group to determine the features that both males and females present with

RESULTS: Characteristic pre-treatment dental features of the sample included maxillary incisors that were proclined and protruded with resultant decreased interincisal angle, mandibular incisors which were favourably positioned. Skeletal features included retrognathic jaws (maxilla to a greater degree) resulting in a mild to moderate Class III skeletal pattern but with females exhibiting a smaller ANB angle indicating a greater tendency for a Class III skeletal pattern. The skeletal growth pattern was vertically directed with an average anterior facial height ratio

CONCLUSION: The findings indicate that most BP patients in this South African Black population presented with dentoalveolar protrusion, retrognathic jaws and a mild to moderate skeletal Class III pattern

Keywords: Bimaxillary protrusion, Black South Africans, facial profile, facial aesthetics

INTRODUCTION

Bimaxillary Protrusion (BP) is a well reported form of malocclusion characterised by protrusive incisors with resultant protrusion of the lips. As a result of the anaesthetic facial appearance brought about by this increased procumbency, many people seek orthodontic care in order to reduce this procumbency.1,2,3 A review of the literature reveals that grey areas exist regarding the diagnosis of bimaxillary protrusion. It is not clear whether the facial protrusion is solely due to incisor proclination, protrusion or both and whether there is also involvement of the dentoalveolar bases.4

Culture, ethnicity, society as well as personal preferences all play an important role in determining whether individuals will seek orthodontic treatment or not. The interpretation of the many published studies performed on the Caucasian5 and African American populations6,7 must be done with caution as they may not be applicable in a South African population, comprising of ethnic groups that differ in cultural and social dictums. Beukes, Dawjee and Hlongwa8 and Dawjee, Becker and Hlongwa9 determined what Black South Africans regard as a pleasing and acceptable facial profile. It was determined that the need for therapeutic intervention was dependent on the severity of the incisor protrusion, the ability of the patient to close the lips without strain and the patients desire to modify their appearance.

The aim of the study was to perform cephalometric radiographic analyses of dental and skeletal structures of a sample of South African patients presenting with BP in order to identify characteristic features.

METHODOLOGY

Sample size and selection

The research project was approved by the Sefako Makgatho University Research Ethics Committee (SMUREC) prior to commencement (Protocol number: SMUREC/D/125/2018: PG).

This was a descriptive retrospective record-based study. The sample consisted of 67 patients divided into 28 males and 39 females with a mean age of 17.8 years. The sample size was found to be sufficient according to the Central Limit Theorem and comparative analysis of similar published studies.10,11 The study population consisted of individuals who visited the department of orthodontics at the Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University and were clinically diagnosed with bimaxillary protrusion. These were patients who presented with varying degrees of lip separation at rest, mentalis strain, gummy smile or anterior open bites. Standard pre-treatment lateral cephalometric records of patients treated from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2020 were visually assessed by the principal researcher and again re-assessed by the supervisor and only those of superior diagnostic quality were selected for the study. Lateral cephalometric radiographs of patients with craniofacial abnormalities, a history of trauma, prior orthodontic treatment, orthognathic or cosmetic surgery were excluded from the study.

Cephalometric analysis

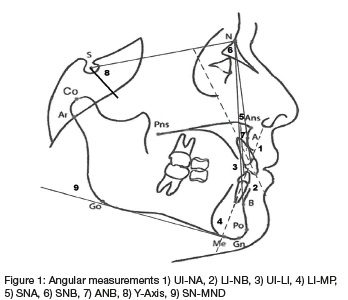

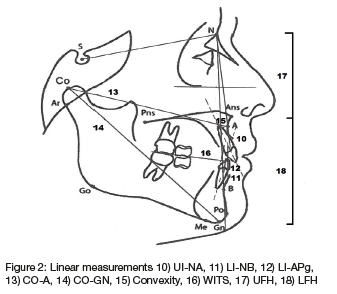

A standardized method of cephalometric measurement using a fine-point 4H pencil and lead acetate paper was carried out by the researcher. All lateral cephalograms were traced as shown in (Figures 1 & 2) and parameters indicated (Table I) were measured. Intra-reliability measurement test was performed by the principal researcher as well as an inter-reliability test by the supervisor at two different time intervals where 10 lateral cephalograms were chosen at random and were re-traced and re-measured to determine the reliability of data. Strict adherence to inclusion and exclusion criteria was adhered to in order to avoid sampling bias. Measurement bias was minimised by tracing no more than 10 cephalograms at a time to avoid operator fatigue.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed on the SAS (SAS Institute Inc. Carey. NC, USA), release 9.4 running under Microsoft Windows. All statistical tests were two-sided and p values < 0.05 were considered significant. Where applicable, measurements from the study were compared to normative values (Table II) using the t-test from relevant literature sources.

The data analysis included comparisons of gender and race, and comparisons of subgroups of patients was performed if there was any clinical interest. Where applicable 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

RESULTS

Characteristic features of bimaxillary protrusion

Table III illustrates the differences in the dental and skeletal variables in a sample of South African black patients with BP when compared to the established norms.

Dental analysis revealed maxillary incisor protrusion (UI-NA: 10.3 ±3.19 mm) and proclination (UI-NA: 30.8±8.12°). The lower incisors displayed no significant difference from the accepted norms in terms of both their linear (LI-NB: 37.7±7.17mm; LI-Apg: 8.1±2.65mm) and angular positions (LI-NB: 37.7 ±7.17°; LI-MP: 99.0±13.75°). The maxillary and mandibular incisors demonstrated proclination in relation to each other (UI-LI: 107.7±11.98°).

Skeletal characteristics showed a decrease in both the effective midfacial length (CO-A: 83.4±5.21mm) and effective mandibular length (CO-GN: 107.3±5.92mm). The sagittal positional relationship of both the maxilla and mandible in relation to the cranial base was retrognathic (SNA: 82.7±4.90°) (SNB: 78.3±3.86°), with an ANB angle which was decreased (4.2 ±2.87°; p= 0.03), indicating a mild Class III skeletal pattern. In relation to the norm values, the convexity (convexity: 4.3 ±2.46mm) and the WITS values (WITS: -2.9±3.91mm) displayed no statistical differences within the BP sample.

In terms of the vertical relationships the sample exhibited a slight vertical growth pattern according to the Downs analysis (Y-Axis: 70.9±4.43°) with a slight decrease in both the UFH and LFH (UFH: 46.3±3.61mm); LFH: 66.1±5.15mm), although in a ratio which is in line with harmonious relationship.

Tables IV and V compare the cephalometric measurements of males and females with BP to the norms. The characteristic features of BP encountered in the whole sample were the same in both males and females, with the only notable difference in the ANB angle. The male sample revealed that there was no statistically significant difference to the norm in contrast to females which exhibited a significant decrease in the ANB angle (p=0.039)

DISCUSSION

CHARACTERISTIC FEATURES OF BIMAXILLARY PROTRUSION

The facial profiles of patients with BP appear to present with an increased convexity due to the more anterior placement of the skeletal, dental and soft tissue structures which make up the midface5. There have been only a few older studies investigating the skeletal and dental cephalometric features of individuals with well-balanced faces revealing the characteristics of normal occlusion among the South African black population.12,14,15,16,17 This study can be considered one of a few studies on BP in a South African sample revealing the unique skeletal and skeletal features.

Dental features

Flaring of the upper and lower incisors is as a common finding amongst black population groups6,16,18,19 and was similarly noted in this study, particularly more in relation to the maxillary teeth. The maxillary incisors were significantly more proclined and protrusive when compared to the norms established for this population group. The lower incisors aligned themselves more closely to the accepted angular and positional relationships with no real proclination or protrusion present. Findings which are all in conflict to conclusions drawn from studies performed on the Zimbabwean population2 which reported maxillary incisors that were retroclined and mandibular incisors that were severely proclined. The inter-incisal angle (UI-LI: 107.7±11.98°) was found to be more than that reported for African Americans19 and the Sudanese20 with less proclination experienced in the South African context. In contrast, the values reported for Caucasians5, the Taiwanese21 and the Thai11 amount to the sample exhibiting a greater degree of proclination and protrusion.

Skeletal features

A diagnosis of bimaxillary skeletal protrusion is made when both the maxilla and mandible are found to be in protruded positions in relation to the cranial base.22 The results from this study on a sample of South Africans with features of BP excluded the presence of any skeletal protrusion, as they displayed no prognathism of the both the maxilla and mandible. Remarkably the maxilla was found to be retrognathic (SNA: 82.7±4.90°) as was the mandible (SNB: 78.3±3.86°), albeit to a slightly lesser degree.

In terms of the ANB angle, Jacobson in 1975 determined that the ANB angle may be affected by the anatomical position of the Nasion, rotation of the skeletal bases (jaws), lower anterior facial height or the degree of prognathism that the jaws possess. The ANB angle in this situation was slightly decreased at 4.2 ±2.87° (p = 0.03) suggesting a mild Skeletal Class III pattern given the applicable norm (5°). This finding may be attributed to a mismatch of the relationship between the SNA and SNB which are reduced, but with a SNB angle which is reduced to a lesser degree. The Zimbabwean2 and Caucasian5 populations featured a Class II skeletal pattern which presented with an increase in the ANB angle attributed to a downward and backward rotation of the mandible, except in the Zimbabwean study2 which implicated a mismatch in a small SNB angle, to a larger SNA angle. A notable feature among Asian population groups is the presence of a decreased ANB, translating to Class III skeletal pattern11,21 as is observed in this sample group. The presence of a mild Skeletal Class III pattern makes these patients ideal candidates for consideration of camouflage treatment.23

The presence of growth in a slightly more vertical direction is indicated by an increased value of the Downs Analysis (Y-Axis: 70.9±4.43°) and suggests that individuals with BP tend to be hyperdivergent. These findings are in agreement with those studies performed on Afro-Caribbeans,24 Sudanese20 and Caucasian populations5. However, these findings were inconsistent with the horizontally directed growth pattern found in Zimbabweans,2 Arabs25 and Asians.11 The UFH (46.3±3.61mm) and LFH (66.1±5.15mm) although slightly reduced, remains in a ratio which is in line with harmonious relationship. The presence of only a slightly vertical growth pattern in addition may have significant positive effects. Orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances usually tends to have extrusive effects23 and can assist with the correction of the mild Class III skeletal pattern as the mandible rotates downwards and backwards during treatment.

In summary an increased facial convexity in South African black patients was a result of bimaxillary dentoalveolar protrusion. There was no element of skeletal prognathism from either the maxilla or mandible. These patients also exhibited a slightly increased vertical direction of growth with males and females displaying very similar cephalometric features except a decrease in the ANB angle in females indicating a tendency to a more Class III skeletal pattern.

CONCLUSION

When compared to cephalometric norms established for the South African Black population, the characteristic features that BP patients present with include: • Proclination and protrusion of the maxillary incisors but favourably positioned and inclined mandibular incisors.

This resulted in an increased interincisal angle.

• The maxilla and mandible are both retrognathic, however the maxilla to a greater degree than the mandible resulting in a mild Class III skeletal pattern.

• The presence of a slight vertically directed growth pattern with average anterior facial height ratios.

• All characteristic features of BP are the same in males and females, except that females exhibit a smaller ANB angle indicating a greater tendency for a Class III skeletal pattern.

These findings conclude that characteristic features of the South African Black population presenting with BP are unique and highlights the importance of knowing and understanding these unique features when diagnosing and planning treatment for this population group.

REFERENCES

1. Bills DA, Handelman CS, BeGole EA. Bimaxillary dentoalveolar protrusion: traits and orthodontic correction. Angle Orthod. 2005 May;75(3):333-9. [ Links ]

2. Dandajena TC, Nanda RS. Bialveolar protrusion in a Zimbabwean sample. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003 Feb;123(2):133-7. [ Links ]

3. Huang YP, Li WR. Correlation between objective and subjective evaluationof profile in bimaxillary protusion patients after orthodontic treatment.Angle Orthod 2015 Jul;85(4):690-8 [ Links ]

4. Sivakumar A, Sivakumar I, Sharan J, Kumar S, Gandhi S, Valiathan A.Bimaxilary protrusion trait in the Indian population: A cephalometric study of the morphologicaç features and treatment considerations. Orthodontic Waves. 2014;73(3):95-101. [ Links ]

5. Keating PJ. Bimaxillary protrusion in the Caucasian: a cephalometric study of the morphological features. Br J Orthod. 1985 Oct;12(4): 193-201. [ Links ]

6. Fonseca RJ, Klein WD. A ceaphalometric evalution of American Negro women. Am J Orthod. 1978 Feb;73(2):152-60. [ Links ]

7. Leonardi R, Annunziata A, Licciardello V, Barbato E. Soft tissue changes following the extraction of premolars in nongrowing patients with bimaxillary protrusion. A systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2010 Jan;80(1):211-6. [ Links ]

8. Beukes S, Dawjee SM, Hlongwa P. Soft tissue profile analysis in a sample of South African Blacks with bimaxillary protrusion. SADJ. 2007 Jun;62(5):206, 208-10, 212. [ Links ]

9. Dawjee SM, Becker PJ, Hlongwa P. Is orthodontics an option in the management of bimaxillary protrusion? SADJ. 2010 Oct;65(9):404-8. [ Links ]

10. Dandajena TC, Nanda RS. Bialveolar protrusion in a Zimbabwean sample. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003 Feb;123(2):133-7. [ Links ]

11. Lamberton CM, Reichart PA, Triratananimit P. Bimaxillary protrusion as a pathologic problem in the Thai. Am J Orthod. 1980 Mar;77(3):320-9. [ Links ]

12. Grimbeek JD, Cumber E, Seedat AK. Cephalometric analysis of black patients, South African Division Twenty-first Scientific Congress. 1987 Aug 31- Sep 2; Cape Town, South Africa. [ Links ]

13. Dawjee SM. The introduction of a new lateral cephalometric method and its potential application in open bite deformities. PhD Thesis. South Africa: University of Limpopo; 2010. [ Links ]

14. Wanjau J, Khan MI, Sethusa MPS. Applicability of the McNamara analysis in a sample of adult Black South Africans. SADJ. 2019 Mar; 74(2): 87-92. [ Links ]

15. Naidoo LC, Miles LP. An evaluation of the mean cephalometric values for orthognathic surgery for black South African adults. Part II: Soft tissue. J Dent Assoc S Afr. 1997 Sep;52(9):545-50. Erratum in: J Dent Assoc S Afr 1997 Nov;52(11):677. [ Links ]

16. Jacobson A. The craniofacial skeletal pattern of the South African Negro. Am J Orthod. 1978 Jun;73(6):681-91. [ Links ]

17. Barter MA, Evans WG, Smit GL, Becker PJ. Cephalometric analysis of a Sotho-Tswana group. J Dent Assoc S Afr. 1995 Nov;50(11):539-44. [ Links ]

18. Drummond RA. A determination of cephalometric norms for the Negro race. Am J Orthod. 1968 Sep;54(9):670-82. [ Links ]

19. Diels RM, Kalra V, DeLoach N Jr, Powers M, Nelson SS. Changes in soft tissue profile of African-Americans following extraction treatment. Angle Orthod. 1995;65(4):285-92. [ Links ]

20. l hag SB, Abbas S, Ibrahim EK, Hashim HR, Sharfy A. Bimaxillary protrusion in a Sudanese sample: A cephalometric study of skeletal, dental and soft- tissue features and treatment considerations. J of Orthod Research. 2015;3(3): 192-8. [ Links ]

21. Tsai HH. Cephalometric characteristics of bimaxillary dentoalveolar protrusion in early mixed dentition. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2002 Summer;26(4):363-70. [ Links ]

22. Dale JG. Interceptive guidance of occlusion with emphasis on diagnosis. Alpha Omegan. 1999 Dec;92(4):36-43. [ Links ]

23. Ackerman JL, Proffit WR, Sarver DM, Ackerman MB, Kean MR. Pitch, roll, and yaw: describing the spatial orientation of dentofacial traits. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007 Mar;131(3):305-10. [ Links ]

24. Carter NE, Slattery DA. Bimaxillary proclination in patients of Afro-Caribbean origin. Br J Orthod. 1988 Aug;15(3):175-84. [ Links ]

25. Aldrees AM, Shamlan MA. Morphological features of bimaxillary protrusion in Saudis. Saudi Med J. 2010 May;31(5):512-9. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Muhammed Ikhwaan Osman

P.O. BOX 19845, Pretoria West, South Africa, 0117

Tel: 082 418 9542; Email: osmanorthodontics@gmail.com