Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.77 no.4 Johannesburg Mai. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2022/v77no4a4

RESEARCH

The perceived business management knowledge and skills of dentists in private practice in South Africa

V Daya-RoopaI; CP OwenII

IBDS, MScDent, MBA, MPH, Private practice, Johannesburg, South Africa. ORCHID Number: 0000-0002-9602-2778

IIBDS, MScDent, MChD, FCD(SA), Emeritus Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. ORCHID Number: 0000-0002-9565-8010

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: This study evaluated the perceived business (practice) management knowledge and skills of dentists involved in the management of a private practice in South Africa by means of a self-administered web-based questionnaire.

METHOD: Invited participants were members of the South African Dental Association (numbering 2,462) as well as dentists in their second and third year of practice after graduation (numbering 199). There were 533 respondents but not all of these were involved in management and 63 of these failed to complete the survey, leaving a total of 367 respondents.

RESULTS: Overall, the respondents reported that their undergraduate training had not prepared them adequately for the non-clinical aspects of practice management; 56% had not had a formal undergraduate course. However, for those who did, 71% reported that the course was only slightly or not at all useful. Only 29% attended any form of postgraduate course, but only three of these were considered to be effective. Management knowledge and skills were also obtained from accountants as well as financial advisors, friends, family and lawyers

CONCLUSION: In line with the opinion expressed by the majority of respondents (86%), it is recommended that appropriate dental practice management courses be introduced throughout the curriculum, preferably in association with a Business School, and that postgraduate courses should be made available for continuous professional development in this field.

Keywords: Dental practice management; business management; practice management courses

INTRODUCTION

A private dental practice is a small business, operating to provide a health care service and generate a profit, which determines the personal income of the operating dentist. A general dentist, usually the owner of the practice, has to facilitate managerial and administrative tasks similar to any business. However, it has been shown that many dentists and dental students perceived their undergraduate dental curriculum to have lacked non-clinical training in areas such as business management, practice management and leadership skills. 1-6 Many dentists and dental students also believe dental schools should include or improve programmes on non-clinical training in the undergraduate curriculum or offer this as a postgraduate course. 2-5,7

Dental practices are capital intensive and have one of the highest costs per square metre of any small business. 8,9 Therefore, being able to develop a business model that increases revenues is important to guarantee growth. With little or no training or experience, most dentists depend on their reputation, practice location and professionalism for success in business. However, these aspects are considered insufficient to receive the expected revenue in the long term.10 Modern dental practices require deliberate management and sound business knowledge which requires specialized training.1,2

A study in the U.S.2 revealed that 85% of the dental graduates surveyed felt uncomfortable with their practice management education and only 7% felt comfortable with their knowledge of accounting, human resources and dental insurance. The perception of this knowledge and their confidence levels increased significantly only after having spent several years in the workforce. This study also reported that the majority of graduates believed there was a need for the curriculum to include practice management especially health insurance, finance, and accounting. Some of the respondents suggested that practice management courses should be introduced in earlier years of the dental curriculum and should be in collaboration with Business Schools. 2

In 2014-15, a study on non-clinical skills and dental practice management in the four dental schools in South Africa found that students perceived non-clinical skills as being important for clinical care and managing services, but indicated that there should be a greater focus on leadership, business skills and management training. 5

In 2016, a survey of the views of new graduates and established practitioners of their undergraduate training in the United Kingdom revealed that a greater emphasis was needed to teach business and practice management and communication skills.6 A recent U.S study11 of dental schools with and without an associated dual dental/medical MBA programme reported that most (95%) respondents acknowledged that dental practice required business acumen and 68% of those in schools without an associated MBA programme would welcome such a programme. Unfortunately for statistical purposes all respondents were considered together so it was not possible to compare schools with and without the MBA programme. Nevertheless, only 12% reported that they were satisfied with the business-related training offered. Specific items of training, though, were not covered.

A survey of the 10 Canadian dental schools revealed a total of 22 practice management courses ranging from 27 to 109 hours of teaching and were taught by dentists on three main topics: ethics, human resource management, and running a private practice. However, no opinions on the efficacy of these courses were sought.12

The present study aimed to evaluate the perceived business (practice) management knowledge and skills of dentists involved in the management of private practices in South Africa to determine how well equipped they were to manage the practice. It was felt that this information might also provide guidance for improving current undergraduate curricula including the need for postgraduate training.

METHODS

Ethical clearance was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the authors' institution (clearance number M170569). The study was carried out in 2018 and was voluntary, anonymous and there were no consequences for choosing to participate or not participate in the study or from withdrawing. There were no incentives for participation and there were no unintended consequences identified.

The study was a quantitative and qualitative (mixed) questionnaire-based study pertaining to participants' views and perceptions. Hence a self-administered questionnaire was appropriate so that inferences may be drawn from any associations and opinions. The database of the largest national voluntary dental association (which claims on its public website to represent the majority of dentists in the country) was used to distribute the questionnaire. The disadvantage was that only those dental practitioners who were members of the association and who were interested in this topic would have been likely to respond. Nevertheless, it was considered that their opinions on business management would be a guide for the directions the dental curricula could take.

The population sample included dentists who were in private practice (2462) and in addition, those in their second and third year after graduation (199) who would be expected to work in private practice. Dentists in their first year of graduation were excluded as they were within their public-sector community service period and had not been exposed to private practice. Respondents numbered 533; some of these were not involved in management and 63 failed to complete the survey, leaving 367 final participants. Based on a worst-case estimate for a sample size of 50%, with 5% precision and 95% confidence level, a sample size of 385 would be required. The actual sample size of 367, corresponded to a precision of 4.7%,13 and was considered acceptable.

The questionnaire (available from the authors) was based in part on questions that had been used in similar studies to enable comparisons and contained some open-ended questions. Section A recorded demographics and Section B sought opinions on the relevance of the undergraduate training in light of the respondents' experiences. Section C related to postgraduate training and sources of information used by dentists to improve their knowledge or skills in practice management.

The questionnaire was converted into a web-based version using Qualtrics survey software (Qualtrics, Utah, United States). The dental association distributed an email containing a link to the web-based questionnaire to its members and an attached information letter describing the study explained that participation in the questionnaire would assume consent.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were summarized by frequency and percentage tabulation and continuous variables were summarized by the mean, standard deviation, median and interquartile range, according to their distribution. Participants were categorized into three groups on the basis of the number of years of experience they had in private practice management (0-4 yrs, 5-15 yrs, >15 yrs). One question required participants to rank alternatives and this was analyzed by assigning each response to a category derived from the previous question if possible, or excluded if not. A ranking of 1 was assigned 3 points, a ranking of 2 was assigned 2 points, and a 3 was assigned 1 point. The final ranking was determined by summing the points for each item. Data analysis was carried out in Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) Software Version 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., North Carolina, USA). The 5% significance level was used.

Validity

In terms of external validity, the study was context specific, and limited to dentists in private practice in South Africa. In terms of internal validity, the questions used in the research instrument were short and in a language that was easy for all respondents to understand, with the avoidance of doublebarrelled, loaded and potentially confusing questions. Prior to conducting the study, a pilot study was conducted on part-time faculty members at the University of the Witwatersrand School of Oral Health Sciences who were also working in private practice. Their feedback was obtained regarding the appropriateness and ease of understanding the questions and changes that were required were implemented.

RESULTS

Demographics

The 367 participants represented a response rate of 14%. Of these, 99% worked in the private sector, 8% worked in the public sector, and 1% in other areas (academia, governance or retired). Some participants worked in more than one sector. Of the participants who were involved in managing a private practice (n = 365), the majority were owners (73%), 13% were associates, 9% were co-owners and 4% were either locums or had other roles.

The number of years in practice management (n = 362) were categorized into three groups, 0-4 yrs (n = 116, 32%), 5-15 yrs (n = 116, 32%), and >15 yrs (n = 132, 36%). The median was 10 years (IQR 3-23 years; range 0-58 years).

Undergraduate Preparation for Practice Management

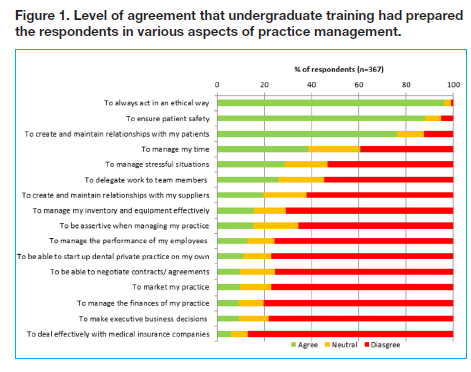

The extent to which undergraduate training had prepared participants in various aspects of practice management is shown in Figure 1, which shows the extent of agreement or disagreement with each of 16 statements, ranked in order of decreasing agreement.

Participants agreed that their undergraduate training had prepared them in the areas of ethics, patient safety and patient relationships. There were mixed responses regarding the level of preparedness around time management, stress management and work delegation. However, there was agreement that undergraduate training had not prepared respondents for all other aspects of practice management.

Undergraduate Practice Management Courses

Fifty-six percent of the participants reported that they had no formal undergraduate practice management course. Of those who had a course, 68% took place in their final year of study. The courses varied in length: 78% were in one year of study, and 18% and 4% were over two and three years of study respectively.

Only 18% found their course to be useful, and 71% found it to be only slightly or not at all useful. Participants were able to comment on this and 64 responses were received: 70% (45) were negative, expressing varying degrees of inadequacy of the course(s) they had received, with comments varying from "Ineffective and useless" through "It didn't feel relevant to equip you in starting your own practice" to "If I remember correctly it was 5 x 60 minutes lectures. With the hindsight of 35 yrs I know that these presentations were a TOTAL waste of time". Ten of the comments did mention some positive aspects such as "Experience cannot be taught but the exposure to private practice was a boost"; "Gave me the basic understanding of management, but not detailed practical advice". It was clear, therefore, that amongst those prepared to comment, the experiences were mixed with by far the majority being negative. An associated question asked participants to reflect on the usefulness of undergraduate training in light of their current experience. Analysis of these responses revealed that 106 (84%) felt that an undergraduate course was necessary, 105 (83%) felt their course was inadequate, and 26 (21%) made content suggestions. Seven respondents specifically suggested both under- and postgraduate courses were necessary. Suggestions for the content of such courses included the following:

• Private practice mentorship

• Finance management of a private practice

• Computer studies

• Control management

• Procurement

• Ethical conduct

• People management and interaction skills, business skills, marketing skills and investment skills

• Exposure to private practice during the undergraduate course

Analysis of Postgraduate Training

Only 29% (n = 97) of the respondents had formal postgraduate business/practice management training. The most common forms of training were Continuing Professional Development (CPD) courses in business/practice management (56%) and management/leadership seminars (45%). None of these courses was perceived as being particularly effective, but the management/leadership seminars and business school degrees were perhaps somewhat more effective than the rest.

Practice Management Course Recommendations

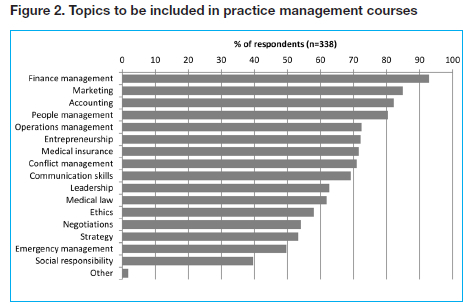

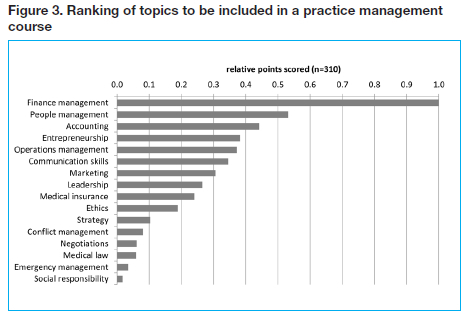

The participants were given a list of all possible topics that could be included in a practice management course, and were asked to indicate the most important topics (Figure 2). They were then asked to rank the top three most important topics which should be included in a practice management course (n = 310) (Figure 3).

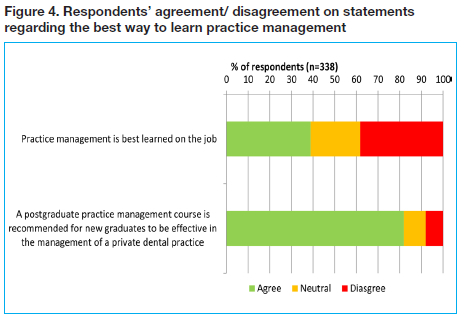

Acquisition of Practice Management Knowledge and Skills The participants were asked to provide information regarding any help they had received in acquiring their knowledge and skills in practice management (n = 338). The most common assistance was from an accountant/auditor (67%). In light of their experience, they were then asked their level of agreement to a series of options to best learn practice management knowledge and skills. The participants (n = 338) were divided on whether practice management was best learned on the job, but strongly agreed that a postgraduate course was needed, and preferred this to on the job learning (Figure 4).

The participants were given an opportunity to freely make any ther comments, and 53 responded. Although a few of these were merely to compliment the researcher on conducting

this survey,18 were comments that were not very helpful or were irrelevant. There were some interesting observations such as "Someone should write a really good book for [local] conditions" and there were four comments suggesting that dentistry is a business first and should be taught as such, although this was countered by one impassioned plea for the opposite attitude.

DISCUSSION

Almost all participants (99%) worked in the private sector. Most (73%) who were involved in the management of a practice were owners. The median number of years in practice management was 10. Young graduates are likely to stay on in the public sector following community service or to practice as a locum dentist under a more experienced dentist for a few years, gaining experience, before owning or managing a practice.1

The majority of participants agreed that what training they had received had prepared them in areas of ethics, patient safety and relationship building with patients. This is understandable as the curriculum in most dental schools is likely to place an emphasis on these aspects. There were mixed responses regarding the level of preparedness around time management, stress management and work delegation. Although these are all part of clinical dentistry, there was evidence that there was room for improvement in training these aspects. Overall, most participants agreed that their undergraduate training had not prepared them for most aspects of practice management. These results are similar to other studies2,11 which found that the dental curriculum focused on developing skills during clinical education and it was only after graduation that dentists realized that there were many other aspects of practice management that needed development.

In a South African study4 dental students perceived non-clinical skills pertaining to ethics and professionalism as least important; in this study, these were the aspects that participants reported their undergraduate programme had prepared them the most for. These results are also in agreement with studies where dentists and dental students alike, perceived their undergraduate curriculum to be lacking in non-clinical training in business/practice management.1,2,5,6,11

Whilst 34% of respondents did have a formal practice management course, 71% of these found their course to have been only slightly useful or not at all useful. However, 10% did experience the course(s) to be helpful in some aspects.

In a U.S. study,2 dental graduates suggested that practice management courses should be introduced in the earlier years of the curriculum and be continuous throughout, and also suggested collaboration with Business Schools. Another study,11 when proposing a dual dental/medical-MBA course, found that 63% of students would enroll in such a course. In this study, the majority of participants received such training in the final years and 78% reported that the course was only during one year of study. Interestingly, 86% of the participants felt that courses should be offered at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels, while only 10% and 4% felt the course should be offered only at the undergraduate or postgraduate level, respectively. Content suggestions made by participants coincided with the perceived lack of preparation in several aspects of practice management as well as the recommendations for what topics should be included.

Participants in several studies recommended postgraduate training to overcome the lack of time in the undergraduate curriculum.1,2,5,7 Although the majority of the participants in this study recommended postgraduate training in addition to undergraduate training, only 29% reported having pursued some form of postgraduate training. The most common forms were CPD courses in business/practice management (56%) and management / leadership seminars (45%). None of the postgraduate courses attended by participants in this study were perceived to be effective, although the management/leadership seminars and business school degrees were perceived as being slightly more effective than the others. Certificate and CPD courses in business/practice management and diplomas at business school were not as effective. The least effective included online management/ leadership courses, distance learning and diplomas in business/practice management. A reason for this could be that the courses are not in context or tailor-made to dental professionals.

Content suggestions made by participants coincided with their perceived lack of preparation in several aspects of practice management. The majority of participants indicated finance management, marketing, accounting and people management as being the most important topics. Topics such as entrepreneurship, operations management, communication skills, leadership, medical insurance and ethics had less importance. Least important were topics such as strategy, conflict management, negotiations, medical law, emergency management and social responsibility. Other topics suggested, which were not listed, included time management, stress management, tax, labor relations and dental software. These findings correlated with the participants' reports concerning their inadequate preparation to manage the finances of a practice, to market their practice or to manage the performance of their employees.

The results of this study are in agreement with those of Barber et al 2 where the largest area of concern for dentists was accounting, finance, human resources and dental insurance. A study in South Africa14 also found dentists to lack finance management skills and recommended that universities include a finance management course for undergraduate dental studies.

Studies have shown that dentists have to seek help to gain business management knowledge and skills or to assist them in managing some aspect of their practice.2,5,7 Two-thirds of the participants (67%) commonly used the assistance of an accountant/auditor to acquire business management knowledge and skills. Just over 50% relied on their colleagues. Participants also commonly used financial advisors, friends, family members, lawyers and mentors. Management consultants and business coaches were the least likely to be called upon.

Experience alone was considered insufficient to gain the skills to manage a practice and hence a postgraduate course was recommended over learning on the job. These findings were also in agreement with those of Barber et al. 2 who found that practice management skills can take Ave to 10 years or more to gain experientially and recommended that these skills should not be learned on the job, but rather interventions are needed to close the gap between graduates' knowledge and practice.

Without changes to the undergraduate curriculum to include or improve courses on dental practice management, dentists in South Africa will not be prepared to manage a practice in many aspects. Postgraduate practice management courses can be useful to expand on the knowledge and skills developed in undergraduate training as well as to be applied to experience in private practice. It is therefore recommended that all South African dental schools should include courses in dental practice management throughout the undergraduate curriculum, and that it would be preferable to offer such courses together with the University's business school. In addition, South African dental schools, business schools, and private companies should offer postgraduate courses on practice management to expand on the undergraduate curriculum, and the content and delivery of such courses should be continually reviewed, and tailored to dental practice management requirements.

Limitations

The response rate was poor, such that only large effect sizes would be detected as direct statistically significant associations. Nevertheless, results of such a study are extremely useful and are likely to be broadly representative of the opinions of the wider population of dentists, especially in light of the agreements with other studies both in South Africa and internationally.

CONCLUSIONS

Under the conditions and limitations of this study the

following conclusions can be drawn:

• The current undergraduate curriculum in South African Dental Schools is not effective in preparing graduate dentists in most aspects of non-clinical practice management.

• The majority of dentists in private practice in South Africa are unlikely to have had a practice management course during their undergraduate training.

• Of those dentists who did have an undergraduate practice management course, the majority did not And the course at all effective, and most experienced it during only one year of study.

• The most common form of postgraduate training attended by dentists was continuing education courses in business/practice management and management/ leadership seminars.

• Most forms of postgraduate training were found to be not relevant to a dental practice.

• The majority of respondents recommended that a practice management course should be offered throughout the undergraduate curriculum, as well as at postgraduate level.

• The most important topics recommended to be included in a practice management course were finance management, accounting, marketing and people management.

• The majority of respondents required the help of an accountant, a colleague and a financial advisor to acquire business/practice management knowledge and skills.

• The majority of dentists suggested postgraduate training would be more valuable to gain management knowledge and skills rather than on-the-job-learning.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the South African Dental Association for their assistance in distributing the survey to the study population, and to the participants for taking the time to respond to the survey.

REFERENCES

1. Chambers DW. The continuing education business. J Dent Educ 1992; 56(10): 672-9 [ Links ]

2. Barber M, Wiesen R, Arnold S, Taichman RS, Taichman LS. Perceptions of Business Skill Development by Graduates of the University of Michigan Dental School. J Dent Educ 2011; 75(4): 505-17 [ Links ]

3. Khami MR, Akhgari E, Moscowchi A, Yazdani R, Mohebbi SZ, Pakdaman A et al. Knowledge and attitude of a group of dentists towards topics of a course on principles of successful dental practice management. JDM 2012; 25(1): 41-7 [ Links ]

4. Van Der Berg-Cloete SE, Snyman L, Postma TC, White JG. Dental students' perceptions of practice management and their career aspirations. Afr J Health Professions Educ 2015; 7(2): 194-8. [ Links ]

5. Van Der Berg-Cloete SE, Snyman L, Postma TC, White JG. South Africa dental students' perceptions of most important nonclinical skills according to Medical Leadership Competency Framework. J Dent Educ 2016; 80(11): 1357-67 [ Links ]

6. Oliver GR, Lynch CD, Chadwick BL, Santini A, Wilson NHF. What I wish I'd learned at dental school. Brit Dent J 2016; 221(4): 187-194 [ Links ]

7. Skoulas A, Kalenderian E. Leadership training for postdoctoral dental students. J Dent Educ 2012; 76(9): 1156-1166 [ Links ]

8. Fiore J.. Dental Practice Start-Up: Top-10 Tips For Success. 2015. https://www.bankofamerica.com/content/documents/practicesolutions/TipsDentalStartUp.pdf Accessed 20 April 2017 [ Links ]

9. Amos J. Dental Practice Start-up Costs: The TRUE Price To Open A New Office. 2016; http://howtoopenadentaloffice.com/dental-practice-start-up-costs/ Accessed 20 April 2017 [ Links ]

10. Alaabed, A. Professional Dental Practice Management (editorial). Smile Dental Journal, 2016; 11(1): 6-7 [ Links ]

11. Han JY, Paron T, Huetter M, Murdoch-Kinch CA, Inglehart MR. Dental Students' Evaluations of Practice Management Education and Interest in Business-Related Training: Exploring Attitudes Towards DDS/DMD-MBA Programs. J Dent Educ. 2018; 82(12): 1310-19 [ Links ]

12. Schonwetter DJ, Schwartz B. Comparing Practice Management Courses in Canadian Dental Schools. J Dent Educ. 2018; 82: 501-509. doi: 10.21815/JDE.018.055 [ Links ]

13. Daniel WW. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences, 10th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2013 [ Links ]

14. Buleni T. Financial management in small dental practices in Witbank and Pretoria, South Africa. A research report submitted to Milpark Business School, Johannesburg, 2015 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Prof CP Owen

Phone: +27-83-6792205

Email: peter.owen@wits.ac.za

Author contributions:

1 . Variza Daya-Roopa: 70%

2.C Peter Owen: 30%