Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.77 no.1 Johannesburg Fev. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2022/v77no1a4

FORENSIC DENTISTRY

Will "selfies" solve the identification crisis in lower socio-economic South Africans? A dental feature analysis of "selfies"

V ManyukwiI; C L DavidsonII; P J van StadenIII; J JordaanIV; H BernitzV

IDental Unit Pholosong Hospital, Tsakane, Brakpan, South Africa 1550

IIDepartment of Oral Pathology and Oral Biology, School of Dentistry, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID: 0000-0002-3638-6932

IIIDepartment of Statistics, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID: 0000-0002-5710-5984

IVDepartment of Statistics, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID: 0000-0001-5678-5853

VDepartment of Oral Pathology and Oral Biology, School of Dentistry, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID: 0000-0003-1361-1225

ABSTRACT

Identification in forensic odontology requires that a known characteristic of an individual's dentition be compared with the same characteristic of the unknown decedent. In South Africa a number of factors render forensic identification of unknown individuals challenging. Many South Africans do not have access to modern dentistry, and consequently do not have ante-mortem dental records. In South Africa, 22 million people are said to own a smart phone, which accounts for close to 40% of the country's population. The aim of the study was to investigate selfies as a source of dental feature information in a government clinic catering to previously disadvantaged patients.

Identifiable dental features were observed in 61 (5.6%) of the collected images (N=1098). The low number of useable selfies collected in this study could be attributed to: a lack of smiles seen in the received images. Individuals with poor dental aesthetics would commonly choose to take a selfie with a closed mouth where their teeth would not be visible. The most commonly identified dental features included: diastemas (49.2%), dental jewellery (37.7%), crowding (16.4%), differencein tooth height (16.3%), discoloured (8.2%) and missing teeth (8.2%). This study found that selfies cannot solve the identification crisis in lower socio-economic South Africans. Awareness of the importance of selfies in forensic identification should be increased.

Key words: Forensic Odontology, identification, record keeping, mobile phones, selfies, dental features.

INTRODUCTION

Rapid and accurate identification of non-natural deaths is a key component of a good forensic service.1 This is important for ethical, criminal and civil reasons.1 Post mortem (PM) identification requires that a known characteristic of an individual be compared with the same characteristic of the unknown decedent. This forensic comparison plays a role in the identification of victims of violence, disasters or mass tragedies.2 If a positive match is found, the individual may be identified and a death certificate can be issued. This provides some degree of closure for an individual's loved ones.

The high number of unidentified decedents at medico-legal laboratory facilities in South Africa (SA) is a source of great concern.3 There are a number of legal consequences for families in cases where a loved one is missing but the death cannot be confirmed. Often there is an absence of medical and dental records especially in the black, previously disadvantaged rural populations of the country. This renders forensic identification of unknown individuals a challenge.3 It is not a rare occurrence to have to identify a person where there is minimal antemortem (AM) data, as in the case of street children, asylum seekers, undocumented foreign nationals and individuals living in remote rural areas.

A lack of DNA reference samples, the high cost of DNA analysis as well as the damage that occurs to fingerprints during the decomposition and carbonization processes present challenges for the identification of unknown individuals.3 An absence of medical and dental records, further hinders the identification process.3 The Covid-19 pandemic has created large pools of vulnerable persons who, due to their worsened economic situation, were recruited for labour or sexual exploitation in their local area.4 Loss of livelihoods and restrictions on movement have led to increased numbers of human traffickers recruiting victims in their local areas.4 Recent statistics reveal that less than 1% of these victims are ever rescued, and that they often have no identification documents which would aid in their discovery.4 A 2016 study revealed that of the world's population,

nearly 70% own a mobile phone.5 Africa has shown phenomenal growth of mobile cellular ownership in recent years. The popularity of prepaid subscriptions and low-cost phones have made it possible for many of the country's youth living in poverty to own or use a phone themselves.5 In SA, 22 million people are said to own a smart phone, which accounts for close to 40% of the country's population.6,7

Current techniques utilised in forensic identification in SA remain more suited for first world countries, where dental records are generally available throughout all socio-economic groups.8 Within SA, alternative methods of identification need to be investigated. Mobile phones are easily accessible and found in most sectors of our population, making selfies a possible source of dental information. Yet, there is minimal information regarding the use of selfies within forensic dentistry.

AIM

The aim of the study was to investigate selfies as a source of dental feature information in a government clinic catering to previously disadvantaged patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients older than 18 years that attended a Provincial Hospital dental clinic from November 2019 to May 2020 were requested to provide a single selfie photograph of themselves. The selfie could be any selfie of their choosing, of them either alone or in a group. All the collected images were stored on a database and given a unique study number that correlated with their patient file number.

The following patient and selfie information was recorded: age of the individual, gender, ethnicity, date the photograph was taken, as well as the dimensions and size of image. Additionally, a clinical oral examination was performed for each patient as part of their routine dental treatment.

Usability of each of the provided selfie images was assessed and the images were classified as follows:

• Images where the dentition was visible and identifying dental features could be seen. These images were scored 1.

• Images where the dentition was visible but identifying dental features could not be seen. These images were scored 2.

• Images where the dentition was not visible or quality of the image was poor. These images were scored 3.

The images where the dentition was visible were further analysed for a number of identifiable dental features. Intra and inter observer reliability were carried out on 300 random selfies during the analysis period. The data analysis consisted of frequencies and descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations and percentiles.

This study was approved by the Faculty of Health Sciences Research and Ethics Committee. (Ethics number 740/2019) of the University of Pretoria in terms of the National Health Act (Act 61 of 2003) and the Code of Ethics for Research of the University of Pretoria. Participation in this study was voluntary.

RESULTS

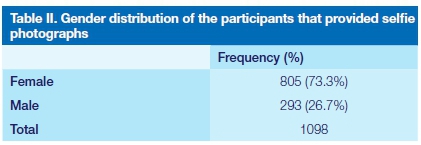

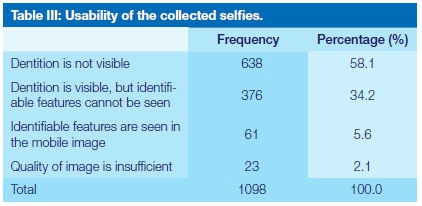

A total of 1 098 selfies were collected during the study period. Table I summarizes the descriptive statistics for the age of the patients that provided selfies. The number of selfies received by females (F=805) was far more than those received by males (M=293) (Table II). The dentition was visible in 437 (39.8%) of the collected selfies. Of these images, 61 (5.6%) selfies showed identifiable dental features (Table III).

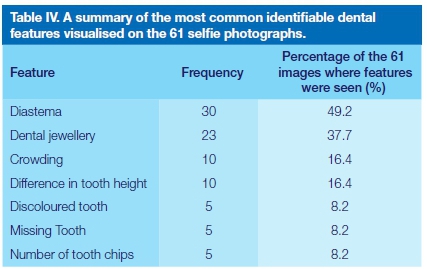

The maxillary anterior teeth were most frequently visible in the collected selfies. The highest frequency of anterior teeth seen was a smile span of 6 visible teeth (n=18). Table IV presents a summary of the most common dental features seen on the 61 selfies where features could be identified.

The intra observer reliability was 0.972 and the inter observer reliability was 0.966 showing a good agreement and reproducibility in the methodology of identifying the dental features.

DISCUSSION

The results of this research unfortunately showed that most of the study participants did not provide smiling selfies. The majority of the selfies that were collected were of individuals with their mouths fully or partially closed. The dentition was visible in 39.8% of the 1098 collected images and identifiable dental features could only be seen in 5.6% of these images (n=61).

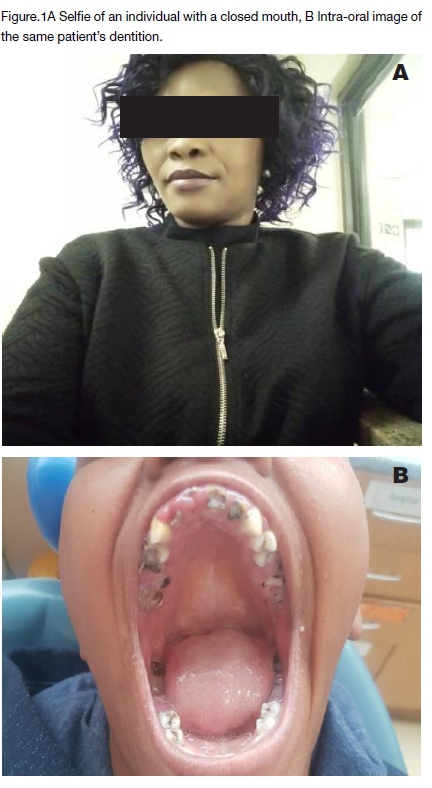

A possible contributing factor to the low number of smiling selfies collected in this study could be the dental /oral health status of the participants. Individuals with poor oral health, tooth loss and untreated carious lesions may be self-conscious and therefore may not take smiling photos or be willing to share such images.9,10 Individuals living in lower socio-economic areas have poor access to oral healthcare and therefore oral health awareness is low.11 The majority of individuals that provided a selfie where their dentition was visible had good oral health with no restorations or dental decay. In contrast, individuals with a poor state of their dentition frequently provided a selfie with a closed mouth where their teeth were not visible.

There was only one selfie collected which showed dental caries in this study (1.6%). In this image it was almost as if the individual was trying to conceal the visible dental decay in their smile line by not smiling widely. This finding emphasized the fact that those with decayed teeth chose to not smile in their selfies. Considering that globally 2.3 billion people are estimated to suffer from caries of permanent teeth, it was surprising to note the low number of dental caries seen in the collected selfies.12

An example where a selfie was provided with a closed mouth can be seen in Fig.1A. This patient reported that she did not want to show her teeth while smiling due to embarrassment about the state of her dentition. After obtaining consent, the investigator took an intra-oral photograph of the individual's dentition which revealed multiple carious teeth and decayed root remnants (Fig.1B). In 2018, Weiser et al. reported that the recent substantial growth of social media has led to more individual self-promotion and competition.13 This could explain why those individuals with undesirable dentition would choose to take a selfie with a closed mouth where their teeth would not be visible. In many of the non-smiling selfies provided in this study, the participants reported that they were self-conscious about their poor dentitions and therefore hid their smiles.

The mean age of the participants in this study was relatively young at 30.5 years old. In the cases where older individuals had camera phones, most reported that they did not take selfies. The availability of selfies for identification is thus generally restricted to younger individuals and may become more difficult to source in older persons requiring identification. This is not an unusual finding as studies have shown that there is a higher prevalence of use and ownership of mobile phones in adolescents than in adults.14 In fact, in the past few years, phone usage rates have also considerably increased among preschool children aged 6-10 years.14

There were more female participants (73.3%) who provided selfies than male participants. This might simply be due to more females attended the dental clinic than men. However, literature has shown that women are more likely to schedule a dentist visit and are more proactive than men in maintaining healthy teeth and gums.15 Furuta et al. claimed that women have a better understanding of what oral health entails, as well as a more positive attitude towards dental visits.15

In 1986, Mckenna et al. investigated the role that anterior dentition visible in photographs can have in forensic identification.16 In their study, 100 different photographs and dental models were studied. They found that 96% of the study participants had at least one feature in their dentitions which could be classified as unique.16 Their study was expanded in which they examined 1000 different photographs to identify the percentage of individuals who showed anterior teeth in their photographs. Their findings revealed that 60.9% of the photographs showed special attributes, or unique dental features and that 76.7% of their collected photographs were usable in the identification of missing and unidentified person. Their results are in sharp contrast to the present study.

There are a number of characteristic dental features that can be used for forensic identification.17 These include the shape of the crown, morphological characteristics, dental anomalies, and alignment between the teeth.

Consideration of the population demographics in which a study is conducted is important when analysing any study data. This study was conducted in Gauteng and the incidence of missing teeth was low at 6.5% (n=5). The most common reason provided by the study participants for having missing teeth, was extraction subsequent to tooth decay. Had this study been conducted in Cape Town, an area known for individuals having a "passion gap" or "Cape Town smile", the incidence of missing teeth would have been higher.18 In the Cape, it is a cultural practice for individuals to electively extract their maxillary central and lateral incisors (teeth 11, 12, 21 and 22) for aesthetic purposes. A selfie from the Western Cape population where all 4 maxillary central incisors were extracted would not be a significant finding.

The more dental features present in one's selfie, the more significant the findings are. Figure 2 is an example of a selfie that showed more than one visible dental feature. In this selfie a non-vital discoloured maxillary central incisor (tooth 21) with a large midline diastema was visible. Maxillary midline diastema was the most common finding in this study (49.2%). If this selfie portrayed an isolated midline diastema, this would not have been a significant finding in this study population. The fact that the individual also has a discoloured tooth 21 adds significance to the dental features. When combined, these 2 dental features are of more forensic significance compared to each feature being found in isolation.

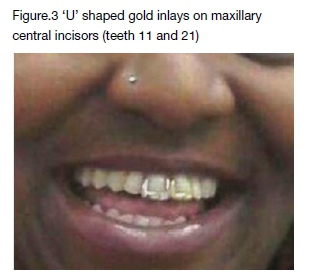

A commonly found feature in this study was dental jewellery on the anterior teeth, which was seen on more than one third (37.7%) of the collected selfies (n=23). Dental jewellery, especially gold inlays and onlays, are a common finding in many different population groups.19,20 The gold slit/inlay was the most commonly seen dental jewellery in this study. For forensic purposes a gold inlay alone would be of little significance. However, if more than one gold inlay is found in one individual (Fig.3) or if two full gold crowns (Fig.4) are found in one individual, the forensic significance is greater.

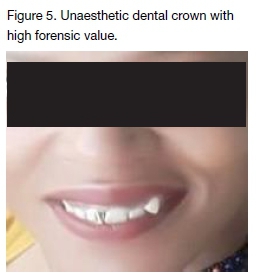

In one of the provided images, a conspicuous unaesthetic, tooth-coloured crown could be seen on the left maxillary canine (tooth 23). This crown was extremely white in colour and positioned out of the dental arch (Fig.5). While this would not be an ideal crown for the patient's aesthetic needs, it provides good forensic identification value. It is highly unlikely that another individual would present with a crown showing similar features to those seen in this selfie. Interestingly, a more clinically pleasing crown would be of less forensic value as it would be less conspicuous and more difficult to see on the image.

Anterior teeth have been shown to have specific numerical rotational value and form part of an individual's unique identity.21 Dental crowding is defined as a discrepancy between tooth size and jaw size resulting in a misalignment of the teeth in the arch.21 The aetiology can include physical trauma, discrepancies in the relationship between tooth size and arch size, emergence of the third molars and periodon-titis.21 Dental crowding was only observed in 10 of the selfies (16.4%) in this study. The last of the most observed dental features in this study was the presence of a difference in tooth height between the upper central incisors. Ten selfies (16.4%) were found to show a difference in tooth height between the maxillary anterior incisors.

A practical example of using a selfie showing characteristic dental features being used for a positive identification can be seen in Figures 6A and 6B. These images clearly show the absolute pattern match between the upper and lower dentition visualised on the AM selfie and the PM image of the victim. In this specific case, a conclusion of absolute certainty was made through the use of the AM and PM images.

When comparing a selfie to a deceased individual's dentition, the orientation of the selfie image and the PM image needs to be considered. An AM photograph is crucial when taking PM photographs, as the angulation of the PM photograph should be reproduced for accurate comparison.22 Mirror images, where the selfie was taken in a mirror, need to be considered as these could be misleading when orientating the selfie.22 Additionally, to avoid any confusion, the investigator should thoroughly correlate the clinical PM examination notes with the photographs of the deceased's dentition. We recommend that during PM procedures multiple angled photographs of the deceased's dentition be taken to use for comparison with a provided selfie, see Figure.7A-C. The angulation of the photograph must be reproduced in the X, Y and Z (depth) axes for accurate comparison.22

Selfies are easy to use, low cost and accessible sources from which dental identification could be performed. From this study it was evident that the more teeth seen in a selfie, the higher the likelihood that the investigator would see identifiable dental features. The 6 most commonly seen dental features in this study were diastemas, dental jewellery, crowding, a difference in tooth height, discoloured and missing teeth.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study were contrary to those that were expected and revealed that selfies cannot solve the identification crisis in lower socio-economic South Africans. This study may not be a true reflection of identifying dental features on selfies as most of the images provided were where the dentition was not visible. Considering the growing trend of selfie taking and the availability of these images, the use of selfies in the forensic identification of individuals still requires further exploration.

Acknowledgements

The first author thanks Dr Ashley Mthunzi for allowing her the opportunity to conduct the study on the Hospital premises.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. This article has not been previously published and is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere.

References

1. Lerer LB KC. Delays in the identification of non-natural mortality. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1998;19(4):347-51. [ Links ]

2. UN. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Trafficking in Persons. Austria; 2020. Impact of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. COVID-19 pandemic on trafficking in persons : preliminary findings and messaging based on rapid stocktaking. Vienna, Austria: UN, May 2020. [ Links ]

3. Evert L. Unidentified bodies in Forensic Pathology practice in South Africa [Masters]. South Africa: University of Pretoria; 2011. [ Links ]

4. UN. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on trafficking in persons and responses to the challenges USA: UNOCD; 2021 [Available from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/2021/The_effects_of_the_ COVID-19_pandemic_on_trafficking_in_persons.pdf. [ Links ]

5. Hodge J. Tariff structures and access substitution of mobile cellular for fixed line in South Africa. Telecommunications Policy. 2005;29:493-505. [ Links ]

6. Where to start? Aligning Sustainable development Goals with citizen priorities [Report]. Afrobarometer. 2015 [cited 21/10/2021]. Available from: https://afroba-rometer.org/sites/default/files/publications/Dispatches/ab_r6_dispatchno67_african_priorities_en.pdf. [ Links ]

7. O'Dea S. Smartphone users in South Africa 2014-2023 [Graph]. South Africa: Statista; 2020 [A graph depicting number of smart phone users in SA from 2014 to 9]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/488376/forecast-of-smartphone-users-in-south-africa/#:~:tex-t=Today%20about%2020%20to%2022,and%20on%20 the%20continent%20overall. [ Links ]

8. Reid KM, Martin LJ, Heathfield LJ. Bodies without names: A retrospective review of unidentified decedents at Salt River Mortuary, Cape Town, South Africa, 2010 - 2017. SAMJ 2020;110(3). [ Links ]

9. Kaur P, Singh S, Mathur A, Makkar DK, Aggarwal VP, Batra M, et al. Impact of Dental Disorders and its Influence on Self Esteem Levels among Adolescents. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(4):ZC05-ZC8. [ Links ]

10. Griffin SO, Jones JA, Brunson D, Griffin PM, Bailey WD. Burden of oral disease among older adults and implications for public health priorities. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(3):411-8. [ Links ]

11. Northridge ME, Kumar A, Kaur R. Disparities in Access to Oral Health Care. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:513-35. [ Links ]

12. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet (London, England). 2018;392(10159):1789-858. [ Links ]

13. Weiser EB. Shameless Selfie Promotion: Narcissism and Its Association with Selfie-Posting Behavior. Shameless Selfie-Promotion. USA; 2017. [ Links ]

14. Fischer-Grote L, Kothgassner OD, Felnhofer A. Risk factors for problematic smartphone use in children and adolescents: a review of existing literature. Neuropsychiatr. 2019;33(4):179-90. [ Links ]

15. Furuta M ED, Irie K, Azuma T, Tomofuji T, Ogura T, Morita M. Sex Differences in Gingivitis Relate to Interaction of Oral Health Behaviors in Young People. J Periodontology. 2011;82(4):558-65. [ Links ]

16. Mckenna J. A qualitative and quantitative analysis of the anterior dentition visible in photographs and its application to forensic odontology [Masters]. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong; 1986. [ Links ]

17. Krishan K, Kanchan T, Garg AK. Dental Evidence in Forensic Identification - An Overview, Methodology and Present Status. Open Dent J. 2015;9:250-6. [ Links ]

18. Allen RW, Gasson JV, Vivian JC. Anaesthetic hazards of the 'passion gap'. A case report. SAMJ. 1990;78(6):335-6. [ Links ]

19. Bhatia S, Gupta N, Gupta D, Arora V, Mehta N. Tooth Jewellery: Fashion and Dentistry go Hand in Hand. Indian Journal of Dental Advancements. 2015;7:263-7. [ Links ]

20. Morris AG. Dental mutilation in southern African history and prehistory with special reference to the "Cape Flats Smile". SADJ. 1998;53(4):179-83. [ Links ]

21. Bernitz H, Solheim T, Owen JH. A Technique to Capture, Analyze, and Quantify Anterior Teeth Rotations for Application in Court Cases Involving Tooth Marks. J Forensic Sci. 2006;51(3):624-9. [ Links ]

22. Robinson L, Makhoba M, Bernitz H. Forensic case book: Mirror image ' selfie' causes confusion. SADJ. 2020;75:149-51. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Vimbai Manyukwi

Dental Unit Pholosong Hospital, Tsakane

Brakpan South Africa 1550

Tel: +27 11 812 5120

E-mail: vimby4@gmail.com

The role played and the respective contribution:

1 . Vimbai Manyukwi: Primary researcher, manuscript preparation

2 . Christy L. Davidson: Supervisor, manuscript preparation and editor

3 . Paul J. van Staden: Conducted statistical analysis

4 . Joyce Jordaan: Conducted statistical analysis

5 . Herman Bernitz: Supervisor, manuscript preparation and editor