Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Dental Journal

versión On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versión impresa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.76 no.3 Johannesburg abr. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2021/v76no3a6

REVIEW

Integrating dentistry into palliative medicine - Novel insights and opportunities

A MajeedI; A AhsanII; M VengalIII; P SampathIV; G VivekV

IBDS, MDS, Oral Medicine and Radiology, KMCT Dental College, Manassery, Kerala, India. ORCID Number: 0000-0001-9735-2691

IIBDS, MDS, Professor and Head of the Department Oral Medicine and Radiology, KMCT Dental College, Manassery, Kerala, India. ORCID Number: 0000-0002-4629-2999

IIIManoj Vengal: BDS, MDS, Professor, Oral Medicine and Radiology, KMCT Dental College, Manassery, Kerala, India. ORCID Number: 0000-0001-8977-2901

IVPrejith Sampath: BDS, MDS, Oral Medicine and Radiology, KMCT Dental College, Manassery, Kerala, India. ORCID Number: 0000-0002-3339-0565

VG Vivek: BDS, MDS, Consultant Dentist (Oral Medicine and Radiology), Dentigo, Iqraa International Hospital, Calicut, Kerala, India. ORCID Number: 0000-0001-9231-3909

ABSTRACT

Palliative care is a global human right, to be provided in a systematic way. The dentist can help the patient right from the initial diagnosis of the condition up to the relief of pain in the terminal stages of the diseases. This inquiry into the oral physician's role on elderly care and special needs would be of benefit to researchers of Palliative Dentistry; particularly in multidisciplinary contexts. This text proposes to discussintegrated oral care, oral health care delivery system, and a flow of educational actions, resources, research, conceptual framework, guidelines and dissemination of newer trends in oral palliative care.

Keywords: Palliative dentistry, geriatric dentistry, mobile dentistry, portable dentistry, palliative oral care.

BACKGROUND

Oral care, in majority of terminally ill patients is often neglected. This is because patients are not always able to receive oral care in their preferred place of care, are often shuttled between sites of care and experience unnecessary hospital admissions as they near the end of life. The patient's emotional, social and economic wellbeing add to these woes. Literature has shown that oral palliative care can have a positive impact on the quality of life of patients; however, the provision of oral palliative care

is often still less than optimal.1-4 There is therefore a need to integrate dentistry to palliative care needs and to disseminate the concept of palliative care amongst oral healthcare professionals. Palliative care dentistry has been defined by Wiseman as the study and management of patients with active, progressive, far-advanced disease in whom the oral cavity has been compromised either by the disease directly or by its treatment; the focus of care is quality of life.5

Palliative care is a global human right, to be provided 'throughout the illness course'.6 According to Obadan-Udoh et al. "providing care that is patient-centered is an indication of quality and that should be our ultimate goal. Dental profession has huge challenges in meeting these expectations."7 The purpose of this article is to offer practical tips and techniques for establishing successful oral palliative care.

Palliative care in South Africa

South Africa has a population of 55 million people of which 62% constitutes the urban population. It is designated an upper middle-income country by the World Bank with $12,730 GNI per capita in 2014. Life expectancy in 2014 was 57 years.8 In 2011, the World Bank report on human resources in health identified that there were 4.7 nurses, 0.8 doctors and 0.085 dentists per 1000 people.8,9 The estimated need for palliative care using only mortality data is that 0.52% of the population requires palliative care in any year. There are currently eight hospital palliative care services (two dedicated children's palliative care services) and 150 hospices providing palliative care, about 40 of them also provide care for children. Funding for palliative care is a limiting factor and a number of hospices closed in the period 2011-2016 for wants of funds.8

The South African National Department of Health (NDoH) requires the support of all government and non-government organizations (NGOs) in their vision of a healthy life for all people of SA. The care provided by hospices takes place mainly within the patient's home. In response to this need Hospice Palliative Care Association (HPCA) adopted the Integrated Community- Based Home Care Model,10 which was developed by the South Coast Hospice in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN). The NDoH recognized this as a best practice model and commissioned HPCA to replicate the model in urban, peri-urban, and rural communities; to determine the cost of the model and to develop a training curriculum for home-based carers.8

The first hospital-based palliative care team in SA was established in Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital in 2001.11 Other important service providers are Wits Palliative Care, Gauteng Centre of Excellence for Palliative Care, and Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto. Of particular note is a program developed from a hospital-based palliative care team established in 1999, which ran the N'Doro project funded by Irish Aid for 3 years (2003 - 2006). They provided specialist palliative care services, outreach visits to the Soweto community, consultations for patients in Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, as well as training of healthcare professionals, conducting research and undertaking advocacy activities for palliative care.12

Despite South Africa having launched the National Policy Framework and Strategy for Palliative Care 2017-2022,13 integrating palliative care into existing public health care is still in its infancy. In 2018, with district wide institutional managerial support, a South African palliative care model for rural areas was initiated in the Western Cape. The process involved setting up hospital- and community-based multi-professional palliative care teams, initiating weekly palliative care ward rounds, training champions in palliative care and raising awareness of palliative care.14

Palliative care in India

In India, organizations like NNPC and Pallium India are making enormous contribution in the field of Palliative care.15 Kerala, one of the southern states of India, has managed to develop an integrated health service delivery model with community participation in palliative care.16

Institute of Palliative Medicine has been playing a major role in shaping up this model. The evolving palliative care system in Kerala tries to address the problems of the incurably ill, bedridden and dying patients irrespective of the diagnosis, age or social class.

The program in Kerala is also expanding to areas like community psychiatry and social rehabilitation of the chronically ill. Palliative care has been declared by the Government of Kerala as part of primary health care. The 'Quality of Death' study by Economist Intelligence Unit (2010) states that "Amid the lamentably poor access to palliative care across India, the southern state of Kerala stands out as a beacon of hope.

While India ranks at the bottom of the Index in overall score, and performs badly on many indicators, Kerala, if measured on the same points, would buck the trend. With only 3% of India's population, the tiny state provides two thirds of India's palliative care services. In April 2008, Kerala became the first state in India to announce a palliative care policy. The Calicut model has also become a WHO demonstration project as an example of high quality, flexible, and low-cost palliative care delivery in the developing world and illustrating sound principles of cooperation between government and NGOs.17

Oral palliative care

Oral palliative care includes access to oral care, regular oral screening, imaging, diagnosing and treating oral diseases like salivary gland disorders, xerostomia, head and neck cancer, temporomandibular joint disorders, myo-facial pain, oral psychosomatic disorders, oral muco-cutaneous disorders, auto immune disorders, oral and maxillofacial frailty, odontogenic and non-odontogenic infection of the jaws, oral manifestations associated with systemic diseases, edentulism, caries and periodontal diseases. They may result from ageing, poor oral intake, drug treatments, local irradiation, oral tumors or chemotherapy. Oral symptoms may significantly affect the person's quality of life, causing eating, drinking, and communication problems, and oral discomfort and pain.15

Geriatric Dentistry is therefore obviously an integral part of palliative medicine which covers all aspects of oral and maxillofacial dysfunctions. Nam et al., in 2017, considered oral and maxillofacial dysfunctions like xerostomia, burning mouth syndrome, taste disorders, swallowing disorders and oromandibular dyskinesia or dystonia as 'oral and maxillofacial frailty' which literally means reduced physiologic functions of oral and max-illofacial region.18 Prevention of these oral complications, early recognition, diagnosis, and management often re-quries the bridging of expertise between both medical and dental care.19

Why oral palliative care so important?

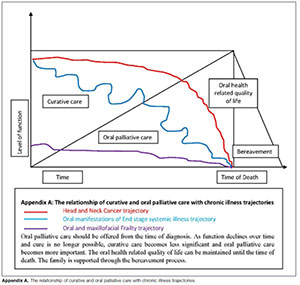

Appendix A depicts the trajectories of oral and maxillofacial disorders which most likely would benefit from oral palliative care. A disease trajectory describes a patient's health status or function over time and may be affected by the availability of health services and treatments.

While head and neck cancer follows a fairly predictable course, oral manifestations as a result of a chronic systemic illness often has periods of acute decline followed by recovery, although the overall function declines over time. Patients with oral and maxillofacial frailty often follow a slow but inexorable decline in function, and care for these patients are often neglected due to improper knowledge on oral palliative care.20

Dentists can help the patient right from the initial diagnosis of the condition up to the relief of pain in the terminal stages of the diseases. But many a times the general dentist is unaware of his responsibilities toward a terminally ill patient. The community is also unaware of the role that a nearby dentist can play.3 It is therefore necessary to sensitize authorities to ensure that the expertise of a dentist is available for palliative care needs.

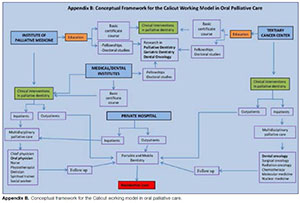

Access to oral care

The need for an integrated model of oral palliative care has prompted the authors to describe a Calicut working model (Appendix B). This is an effective and efficient collaboration between Institute of Palliative Medicine, regional tertiary Cancer Research Centre, Medical/Dental institutions and an NGO palliative care team in a private hospital. It aims to address the oral health problems of institutionalized cancer patients, terminally ill and geriatric patients, especially the frail, special care needs and homebound individuals. Since most of the patients prefer to be at home in the last phase of their life, it is ideal if oral palliative care services are available to them at their residence. Oftentimes, the organizers ensure that the patients are treated on site with minimal interruption of their day or without the complex logistical issues surrounding transportation (Figure 1 and 2). Despite the increased focus on clinical care in the recent decade, oral health professionals have turned to the area of research in palliative dentistry, especially in geriatric dentistry and dental oncology. This has been made possible through basic certificate courses, fellowships and doctoral studies in oral palliative care available in universities across the district.

As the patient's end stage disease progresses, the need for oral palliative care will increase with a concomitant decrease in the level of curative treatment. It is often very difficult to recognize the oral problems, especially for a patient who has an unpredictable disease trajectory.

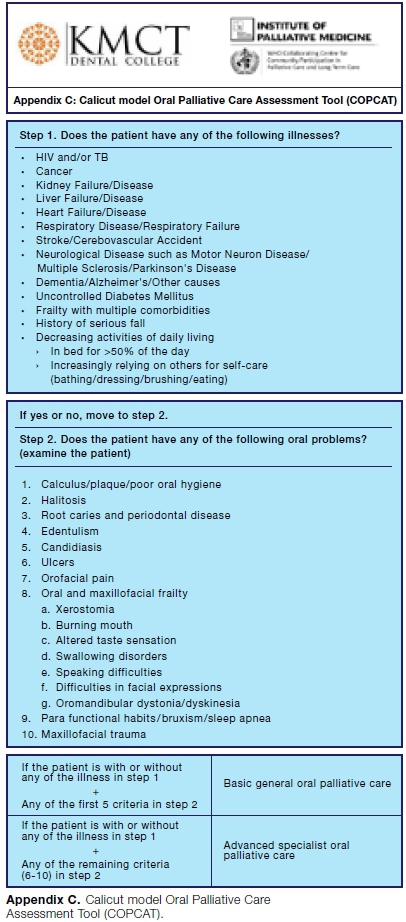

For this purpose, a simple assessment tool has been developed by a private dental institution (Appendix C) in order to identify patients who have unmet oral palliative care, regardless of prognosis. As with any tool, this would need to be validated for use in all settings. Patients who are identified to be in need of oral care interventions can then be further assessed by the appropriate dentist.

Oral health care delivery system

Historically, Portable and Mobile Dentistry (PMD) has been valuable to those for whom transport can be a challenge, like children and the elderly.21 It is very significant to differentiate portable dentistry from mobile dentistry. Portable dentistry entails treating patients at locations such as nursing homes, private homes, and institutions, by transporting dental supplies and equipment from the office to the location. Mobile dentistry on the other hand, involves a dental clinic on wheels in which the patient can be treated within the vehicle.22

Molete et al, in 2014, conducted a cross-sectional study in retirement villages in six district regions in Johannesburg. The aim of the study was to investigate barriers to accessing oral health care amongst an elderly sample residing in government-subsidized retirement villages.

The barriers most frequently reported included the belief that they were not able to afford dental treatment and the lack of transport availability.4 in 2016, another study demonstrated the costs of providing oral health care for school children in a mobile dental unit. The author stated that, it would be possible to expand the service provision to a wider population, particularly in the South African government's plans to integrate school health programs in the primary healthcare re-engineering programme.23

Thema and Singh in 2017, conducted a cross-sectional, explorative and descriptive study using a combination of qualitative and quantitative data to assess oral health service delivery in the public sector in Limpopo Province.

Themes arising from data analysis included lack of policy support; no dedicated funding; and poor oral health representation within different levels of the health system. It has been suggested that, there was an urgent need for re-orientation of oral health services towards prevention and promotion.24

By projecting population data beginning from 1955, Jim Chung, an independent scholar, determined that over the next twenty years, Canada is expected to double her population of people over the age of 65 to ten million.25 This will represent less than 20% of Canada's projected population, and the situation is similar for the US.26

In Western Europe that population will represent over 25% of its total population, and in Japan that number is approaching 40% of its respective population.25 This poses a number of fundamental challenges to the traditional model of delivering dentistry.

In Canada, there is typically too much competition amongst dentists in the big cities, and a shortage of dentists in the rural regions. Jim chung has suggested that, rather than joining a less than busy practice or starting a new practice with zero patients and poor prospects, a new practice model could be a mobile clinic servicing a dozen retirement homes that one could visit twice a month in rotation. Retirement homes are becoming large retirement centres in response to the growing demographic. The retirement homes are privately operated, for-profit businesses and charge their residents a premium for their services.25

Guidelines for oral palliative care in South Africa

The following guidelines constitute an attempt to progressively establish oral palliative care in South Africa.

1. The right to health

Access to oral palliative services over the course of an illness to alleviate unnecessary pain and suffering is a basic human right. The nation's obligation to respect, protect and fulfill this right should be expressed as "A healthy life for all South Africans.''

2. Equitable access

All South African citizens should have access to the essentials of oral palliative care, both in the public and private health sectors and across all service levels. Patients should have access throughout the continuum of care, from diagnosis through treatment, and over the course of their life.

3. Evidence-based research

Oral health care providers should be guided by evidence based practice and locally developed guidelines. Ongoing research, monitoring and evaluation are required to assess and refine quality standards and management guidelines.

4. Patient-centered and ethical care

The provision of oral palliative care must adhere to the principles of medical ethics. It should be an absolute requirement in ensuring oral health related quality of life and dignity of patients from the time of diagnosis until death. Oral palliative care should be accessible and available in facilities for people with disabilities and in care homes for the elderly.

5. Legal and regulatory framework

In order to meet the needs of patients requiring oral palliative care, a national policy framework and strategy in line are required. Such a policy framework and strategy must address the structural challenge, oral health related quality of life and social determinants of health.

6. Social determinants of health

It is difficult to evaluate South Africa's morbidity and mortality without consideration of the social determinants of health. Lack of access to water, sanitation, education and employment all impact the health of the population. It is impossible to have optimal health in South Africa for all, until these social determinants of health are ad-dressed.13 The abovementioned factors also have an impact on the provision of oral palliative care.

7. Governance and financing

Oral palliative care as a health service module has not been determined and therefore adequate funding has not been allocated for the delivery of care. At the organisational level, the National Oral Health Service is dysfunctional. Currently, there is no costing model for oral palliative care in South Africa.27

8. Health resources

A major challenge in providing oral palliative care in South Africa includes a lack of recognized and qualified dentists.9 There is also an absence of curricula, limited formal training and resources, and no clear definition of roles and responsibilities of dentists in the palliative care team. Nurses and other health care workers within the multi-disciplinary team receive minimal training to enable them to recognize the needs of individuals seeking assistance for oral palliative care. Given the relative scarcity of dentists in South Africa (0.085 per 1000 population),9 it has been argued that a health workforce should be developed for the provision of oral palliative care services.

By establishing a rotating internship program for Under Graduate and Post Graduate dental students at the Institute of Palliative Medicine, day care, long term care facilities, tertiary cancer centres or centre for special needs, the availability of dental practitioners can be increased.

9. Service delivery

There is a severe lack of effective communication and appropriately defined care pathways between service providers, resulting in large gaps in the continuum of oral palliative care. Persons in need of oral palliative care should be identified early and should be put onto a specific care pathway with clear referral processes to ensure continuity of oral care throughout the course of the illness. Early identification can be achieved through the use of a clinical assessment tool, which assists health care providers in identifying patients with oral palliative care needs, regardless of prognosis. It is also noteworthy to ensure the availability of PMD in all health sectors.

10. Inter-professional collaboration

Oral palliative care should be developed and maintained through collaboration between relevant national departments through a productive memorandum of understanding (for example, medical/dental institutions, tertiary cancer centers and palliative care centres). There should also be collaboration between government and non-governmental organizations, charitable trusts and religious organizations.

11. Centres of excellence

As the need for oral palliative care is addressed, it will be necessary to establish academic curriculum at the medical/dental institutions, tertiary cancer centers and institute of palliative medicine. The dentist at these centers will be involved in teaching, research, advocacy and service delivery, as in the case of any other academic department. Whilst oral palliative care is currently not recognized as a specialty, the dentist would hold at least a master's degree in Dentistry and a suitable fellowship in palliative care.

12. Information and research

Government/non-governmental sources of oral palliative care information is scarce, making it difficult to access information with regards to the delivery of oral palliative care services. The University of Cape Town and University of the Witwatersrand (Wits Centre for Palliative Care) both have a robust palliative care curriculum embedded within the undergraduate and post graduate medical curricula.13 These institutions are best positioned to initiate clinical and interventional research related to PMD and integrated oral palliative care.

13. Dissemination of newer trends

Publishing the scientific works related to oral palliative care will help identify numerous challenges and barriers that have precluded continuing care to oral palliative care needs. Organizing national or international conferences to congregate the entire perspectives of palliative medicine and dentistry is another way to meet the needs.

14. Dental oncology

A fellowship in dental oncology should be started in tertiary cancer centers. The dental oncologist can play an integral role before, during, and after anti-neoplastic therapies, in order to provide the maximum possibility of functional and aesthetic outcomes. Dental oncologists should be recognized as key members of the multidisciplinary cancer-treatment team.

15. PMD

As Jim Chung suggested,25 the dental practitioners should be encouraged to undergo a paradigm shift from the traditional model of dental care and move towards a model that includes portable and mobile dentistry (PMD).

CONCLUSION

Taken together, the perspective of integrating dentistry into palliative medicine is deeply rooted with the principles of human dignity and appreciation of life, while further reinforced by numerous spiritual values. This will go yet a step further in evoking the moral values and norms of the dentist with respect to enhancement of collaborative opportunities; definitely stating "existence of any matter depends on the priorities."

Such a perspective is however not static, but rather dynamic while nurturing solidarity and support to palliative care needs. Further research on service integration to palliative medicine on the various issues of palliative care needs is nonetheless required to bring about a better understanding of oral health related quality of life.

Financial support

No financial support was taken.

Declaration

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Payne S, et al. Enhancing integrated palliative care: what models are appropriate? A cross-case analysis. BMC palliative care. 2017; 16: 64. [ Links ]

2. Rudolph MJ, Chikte UME, Lewis HA. A Mobile Dental System in Southern Africa. J Public Health Dent. 1992; 52: 59-63 [ Links ]

3. Mol RP. The role of dentist in palliative care team. Indian journal of palliative care. 2010; 16: 74. [ Links ]

4. Molete MP, Yengopal V, Moorman J. Oral health needs and barriers to accessing care among the elderly in Johannesburg. South African Dental Journal. 2014; 69; 352-7. [ Links ]

5. Wiseman M. The treatment of oral problems in the palliative patient. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 2006; 72: 453-8. [ Links ]

6. Harding R, Nair S, Ekstrand M. Multilevel model of stigma and barriers to cancer palliative care in India: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019; 9: e024248. [ Links ]

7. Obadan-Udoh E, Ramoni R, Van Der Berg-Cloete S, White G, Kalenderian E. Perceptions of quality and safety among dental patients. South African Dental Journal. 2019; 74: 374-82. [ Links ]

8. Drenth, C. et al. Palliative Care in South Africa. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2018; 55: S170-7. [ Links ]

9. Strachan B, Zabow T, Van der Spuy ZM. More doctors and dentists are needed in South Africa. South African Medical Journal. 2011; 101: 523-8. [ Links ]

10. Defilippi K. Integrated community-based home care: Striving towards balancing quality with coverage in South Africa. Indian Journal of Palliative Care. 2005; 11: 34. [ Links ]

11. Kirk J, Collins K. Difference in quality of life of referred hospital patients after hospital palliative care team intervention: Clinical practice. South African Medical Journal. 2006; 96: 91-2. [ Links ]

12. Gwyther L, et al. The development of hospital-based palliative care services in public hospitals in the Western Cape, South Africa. South African Medical Journal. 2018; 108: 86-9. [ Links ]

13. National Policy Framework and Strategy on Palliative Care. 2017-2022. Hospice Palliative Care Associate (HPCA) https://hpca.co.za/download/national-policy-framework-and-strate-gy-on-palliative-care-2017-2022/. [ Links ]

14. O'Brien V, et al. Palliative care made visible: Developing a rural model for the Western Cape Province, South Africa. African journal of primary health care & family medicine. 2019; 11: 1-11. [ Links ]

15. Lakhanpal M, Gupta N, Rao NC, Vashisth S. Understanding the Role of Dentist in Specialized Palliative Care. JSM Dent. 2014; 2: 1027. [ Links ]

16. Kumar SK. Kerala, India: a regional community-based palliative care model. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2007; 33: 623-7. [ Links ]

17. Rajagopal MR, Kumar S. A model for delivery of palliative care in India - the Calicut experiment. Journal of Palliative Care. 1999; 15: 44-9. [ Links ]

18. Nam Y, Kim N-H, Kho H-S. Geriatric oral and maxillofacial dysfunctions in the context of geriatric syndrome. Oral diseases. 2018; 24: 317-24. [ Links ]

19. Epstein JB, Güneri P, Barasch A. Appropriate and necessary oral care for people with cancer: guidance to obtain the right oral and dental care at the right time. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014; 22: 1981-8. [ Links ]

20. Lynn J, Adamson DM. Living Well at the End of Life: Adapting Health Care to Serious Chronic Illness in Old Age Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. 2003; (2017). [ Links ]

21. Gupta S, et al. Reaching Vulnerable Populations through Portable and Mobile Dentistry - Current and Future Opportunities. Dentistry Journal. 2019; 7: 75. [ Links ]

22. Friedman PK. Geriatric dentistry: caring for our aging population. John Wiley & Sons, Iowa, USA. 2014. [ Links ]

23. Molete MP, Chola L, Hofman KJ. Costs of a school-based dental mobile service in South Africa. BMC Health Services Research. 2016; 16: 590. [ Links ]

24. Thema K, Singh S. Oral health service delivery in Limpopo Province. South African Dental Journal. 2017; 72: 310-4. [ Links ]

25. Chung J. Delivering Mobile Dentistry to the Geriatric Population - The Future of Dentistry. Dentistry Journal. 2019; 7: 62. [ Links ]

26. Demography - Elderly population - OECD Data. https://data.oecd.org/pop/elderly-population.htm. [ Links ]

27. Motloba PD, Makwakwa NL, Machete LM. Justice and oral health-implications for reform: Part Two. South African Dental Journal. 2019; 74: 208-11. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Abdul Majeed

Oral Medicine and Radiology, KMCT Dental College

Manassery, Kerala, India.

Email: mazid1987@gmail.com

Author contributions:

1 . Abdul Majeed: Primary author - 20%

2 . Auswaf Ahsan: Second author - 20%

3 . Manoj Vengal: Third author - 20%

4 . Prejith Sampath: Fourth author - 20%

5 . G Vivek: Fifth author - 20%