Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.76 no.3 Johannesburg Abr. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2021/v76no3a1

RESEARCH

Evaluation of radiation awareness among oral health care providers in South Africa

P VilbornI; A UysII; Z YakoobIII; T CronjeIV

IBDS, MA Health Management (Finland), MSc Maxillofacial Radiology (UP), Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Oral Pathology and Oral Biology, School of Dentistry, University of Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0001-8296-1689

IIBChD (UP), MSc Maxillofacial Radiology(UP), PhD (UP), Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Oral Pathology and Oral Biology, School of Dentistry, University of Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0001-8250-7662

IIIBChD (UWC), PG Dip Dent Maxillofacial Radiology (UWC), MSc Maxillofacial Radiology (UWC), Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Oral Pathology and Oral Biology, School of Dentistry, University of Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0003-1966-5574

IVBSc (Hons) Mathematical Statistics (UP), MSc Mathematical Statistics (UP), Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, Department of Statistics, University of Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0002-8861-4466

ABSTRACT

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES: The aim of this study was to assess the awareness of oral health care providers and dental students regarding radiation safety, protection and legislation pertaining to dental radiography in South Africa.

DESIGN AND METHODS: An online questionnaire consisting of 20 structured multiple-choice questions was distributed among final year students and oral health care providers.

The mean, median, standard deviation (SD) and frequencies were determined statistically to compare the number of correct answers for each responder group.

RESULTS: In total, 189 questionnaires were analysed. The average number of correct answers was 11.6 out of 20 (58%) for all responders. Dental students presented with the highest percentage (66%) of correct answers

Higher radiation awareness was evident among the respondents who had undertaken continued education courses.

CONCLUSION: Radiation awareness among oral health care providers in South Africa needs improvement. Greater emphasis should be placed on dental radiology courses to increase the knowledge and awareness. However, there is no officially established benchmark of radiation awareness in South Africa.

This conclusion can only be drawn from the responders of the study and cannot be made for the overall awareness of oral health care providers in South Africa.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS: Inadequate radiation awareness and knowledge among oral health care providers may result in contributing to the increased risks of radiation exposure and the erroneous utilization of radiographic imaging.

Keywords: Radiation protection, radiography, dental, dentists, health knowledge, attitudes, practice, South Africa.

INTRODUCTION

Dental radiography plays an essential role in diagnosis and treatment of dental disease.1-2 Oral health care providers, however, do not always follow prescribed indications when performing radiological examinations.3 Radiographs are frequently used for 'routine screening' of new patients.4 An increase in the number of radiographs is also evident when fee-for-service payments are re-ceived.5

Ionising radiation from intraoral imaging is small and comparable to daily natural background radiation.1,6 However, the potentially harmful effects of any radiographic examination cannot be ignored. Each exposure to ionising radiation can cause a biological effect, and increase the potential risk of cancer.7

The use of radiation is accompanied by the responsibility to maintain sufficient knowledge and to ensure appropriate radiation protection.8-10 A need for training with regards to the attitudes towards radiation protection is evident.11-13 The level of knowledge regarding dental imaging and radiation risks also differs amongst different oral health care providers.14

A remarkable divide is evident between patient expectations and the provision of information regarding ionising radiation.15-16 Oral health care providers' knowledge and awareness regarding dental radiology and risks is, therefore, a prerequisite for conducting these discussions to obtain informed consent before imaging.12

South African law permits only registered dentists, radiographers, dental therapists and oral hygienists to perform radiographic examinations.17-18 Chairside assistants are not permitted to take radiographs. In reality, the laws and guidelines related to radiation control and safety are frequently neglected in dental practice.18-19

The aim of this study was to assess the knowledge and awareness of oral health care providers and dental students regarding radiation safety, protection and legislation for dental radiographic imaging in South Africa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional online survey consisting of 20 multiple choice questions was conducted between February to August 2019 (Appendix A). Only registered radiation workers (dental specialists, dentists, and oral hygienists and dental therapists) and final year oral hygiene and dentistry students from the University of Pretoria were invited to participate.

Quantitative variables and demographic data (years in practice, profession, public or private setting and continuous professional development (CPD) in oral and maxillofacial radiology (OMFR) after graduation), were measured with an online questionnaire using the Qualtrics®xm survey platform.

The chosen metric for the level of the knowledge was the percentage of questions answered correctly. Two inclusive questions were added to minimize bias. The questions were based on questions used in similar studies as well as questions formulated specifically for this study.3,12-13,20

The mean, median, standard deviation (SD) and frequencies were evaluated by using R Core Team (2018).21 Additionally, the data was also analysed using the Shapiro Wilk test for normality, Kruskal-Wallis test with a post hoc Dunn test combined with a Bonferroni adjustment, Mann-Whitney-U test as well as the Spearman's Correlation analysis.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Pretoria Faculty of Health Sciences (Ethics reference number: 435/2018).

RESULTS

The final number of 189 returned questionnaires were analysed. Since the dental therapists' sample only consisted of 2 (1%) respondents, the group was combined in analysis with oral hygienists and named Therapist & Oral Hygienist group. Figure 1 presents the qualification, percentage and number of respondents in each group.

The variability of years of experience had a mean of 11.88 years (SD ± 12.14 years). The dental and oral hygiene students were excluded in the calculation of years of experience as they were not yet registered as qualified professionals. The most common practice setting was a private practice (49%), followed by a public setting (42%), whereas only a few settings were indicated as other. The number of respondents who confirmed that they have had CPD training in OMFR during the past Ave years, was 53%, while 8 respondents did not submit an answer to this question.

Overview of radiation awareness

The overall average percentage of correct answers was 58 %, (SD ± 13.43). Dental students (66%, SD ± 10.72) scored the highest average of correct answers, followed by the dental specialists (63%, SD ± 9,98). Dentists and oral hygiene students submitted 58% of correct answers (SD ± 12.16 and ± 8.66, respectively). The least number of correct answers was 49% (SD ± 14.44) for the Therapist and Oral Hygiene category.

The Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to determine if a significant difference exists between the score obtained by each study group. A post hoc Dunn's test, with a Bonferroni adjustment, was then used to investigate between which groups the differences exist. A statistically significant difference (p<0.05) was found between the following groups: Dental Student- Therapist and Oral Hygienist, Dental student - Dentist, Dental Specialist -Therapist and Oral Hygienist and Dentist - Therapist and Oral Hygienist groups. There was no statistically significant difference between the remaining groups.

The association between the score and years of experience was assessed using a Spearman correlation test. The correlation value was -0.306 indicating a negative relationship between the questionnaire score of correct answers and the number of years in practice. A non-parametric Mann Whitney U test was used to determine if a significant difference exists between the results of the groups practising in a public compared with the private sector. The p-value (0.0044) of the Mann-Whitney Wilcox on indicates the statistically significant difference between public and private sector results. The average score of correct answers for the private sector was 54% and the public sector 60%.

The p-value (0.01274) results showed a statistically significant difference between the responders who had CPD training in OMFR in the last 5 years and those with no training. The mean value of the two groups was 55% and 60% respectively.

The differences between dental specialists and dentists were also tested. The Shapiro- Wilk test for normality results showed that normality can be rejected at a 5% level of significance for the dentists' scores. Since not all assumptions held, the non-parametric Mann Whitney U tests were used to determine if a significant difference exists between the results of the two groups.

The p-value (0.1354) of the Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon indicates no significant differences exist between the scores of these two groups.

The low-scoring questions

Eight questions had a correct score of less than 50%. The results and respondent groups with the questions to the lowest scoring questions are presented below in Figure 2.

Question 2 and 14 were mutually inclusive and assessed the knowledge related to the amount of radiation received during dental radiological examinations. Results to question 14 indicated that 61% knew that ionizing radiation used in radiological examinations in dentistry has similar properties to normal background radiation.

Results to question 2 indicated that 42% of respondents correctly knew that the average radiation dose received from one digital periapical radiograph can be considered lower or can be compared with the average daily background radiation dose and 23% were unsure.

Question 9 assessed the awareness of the full-body radiation dose limit of 1 mSv for the general public per year. The results indicated that 49% knew the amount of the annual full-body radiation dose limit for the general public.

Only 49% of the responders were aware of certain conditions enabling the exemption of wearing personal monitoring badges in dental clinics in South Africa, which was assessed in question 15.

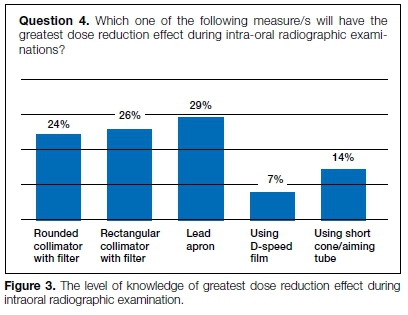

As Question 4 (Fig. 3) was a multiple-choice question, the results of the chosen answers have been additionally presented to illustrate the level of knowledge of greatest dose reduction effect during intraoral radiographic examination. Only 26% of respondents knew that using a rectangular collimator with a Alter helps to achieve the highest dose reduction effect.

DISCUSSION

The study assessed the knowledge and awareness of oral health care providers and dental students regarding radiation safety, protection and legislation. All oral health care providers groups were invited to respond to this study. The reason for the low response rate from the dental therapists may be due to the lack of interest shown towards dental radiology. Nevertheless, their scope of practice permits them to take and interpret the full spectrum of images.22

There is no officially established level of satisfactory radiation awareness in South Africa as no such study was performed. However, the current grading system at South African Universities requires students to obtain a minimum of 50% as the overall mark for dental and oral hygiene students in OMFR. Hence a final mark of 50% can be considered as a satisfactory benchmark when assessing awareness for practicing oral health care providers in

South Africa. In addition, the answers can also be compared to similar studies from other countries, however the questionnaires and requirements may differ.

The results from this study, indicated that radiation awareness among oral health care providers in South Africa is satisfactory as the mean percentage of correct answers was 58%. The results are comparable to Nigeria23 and Poland,12 where 59.1% and 64% of correct answers were respectively recorded. The needs for CPD courses, which include theoretical and practical training, is, however, evident.

The mean percentage of correct answers among dentists was 58% . It must be noted that the undergraduate curricula have changed dramatically due to the importance and demand of OMFR. Former undergraduate training lacked sufficient practical exposure to digital radiography and Cone Beam Computer Tomography (CBCT).

Involvement in the form of communication, training and education from the regulatory bodies also needs improvement. However, courses offered in OMFR and radiation safety may not always be as attractive compared to other clinical courses, which may provide financial gain.

The Dental Students and Specialist's category presented with a higher percentage of correct answers compared with the other responder groups. This can be due to the novel and more comprehensive training received in OMFR. The current curriculum, which includes rigorous training in radiation physics, safety, and CBCT, prepares the students better as the results indicate. Dental students scored higher compared to the dentists. This is in contrast to Poland, where dentists showed higher radiation awareness.12

The Public oral health care sector in South Africa seems to have a more established radiation safety culture compared to the private sector. In our study, oral health care personnel practising in the private sector showed poorer knowledge of radiation awareness (54%) compared to their public sector colleagues (60%). Privately practising dentists may not receive sufficient information on radiation safety and implementing a radiation awareness culture in the dental practice needs expertise and a conscious effort.24

Continues education increased the percentage of correct answers. A statistically significant relationship existed between having received CPD training in OMFR in the last 5 years and the awareness of the greatest dose reduction effects. Studies in Sweden11 and Poland12 presented with similar results. In contrast, no significant associations were found when shorter courses ranging from one to three days were attended .11

Only 42% of responders knew that ionizing radiation used in dental radiographic imaging has similar properties to normal background radiation. However, 61% were aware that the average radiation dose received from one digital periapical radiograph can be considered lower, or can be compared with the average daily background radiation dose. The low knowledge level regarding radiation doses will complicate patient communication.25

The damaging effects of ionizing radiation can be classifled either as deterministic or stochastic. Deterministic effects cause tissue reactions and occur only when certain exposure thresholds are reached, which never happens with exposure levels used in dentistry. Hence, only stochastic effects can occur.26 In our study, only 16% of respondents were aware that dental radiographs cannot cause both effects. Insufficient knowledge of radiation doses and biologic effects may potentially lead to unnecessary or insufficient utilization of radiographic imaging. In both cases, the result can lead to an increased risk for patients.

A rectangular collimator can reduce radiation exposure by 60% compared with a circular collimator.27 Only 26% of all our respondents were aware of the effects of a rectangular collimator with a Alter and only 11% of the dentists answered this question correctly. We also determined that the oral health care providers who had training in OMFR had more knowledge regarding the greatest dose reduction effects. However, our study only assessed knowledge and not practice. Our results were similar to a Korean24 study (20%) and higher than previous studies in Belgium, Iran and Australia, where rectangular collimator was used only by 5% - 6% of dentists.13,20,24,28

It is alarming that 29% of our respondents incorrectly considered that a lead apron will have the greatest dose reduction effect. It was found that 71% of the oral health care providers were not familiar with the current legislation stating that it is not compulsory to routinely use protective devices like lead aprons and thyroid shields for protection. Outdated knowledge of patient safety measures emphasizes the need for more training and access to updated information.

The lack of set dose limits does not imply that radiographic imaging in dentistry can be performed without justification and optimization.29 A remarkable amount of Norwegian medical students (89%) were unaware that there are no legal dose limits set for the patients as long as the examination is justified.27 In our study, only 31% of respondents from the Dental Student's category and 30% of the dentists answered this question correctly.

According to our results, half of the oral health care providers (50%) incorrectly believed that the law sets the limits to the number of radiographs annually prescribed by dentists. This finding is similar to a Polish study, where approximately half of all the responders knew that such a law does not exist.12 No set dose limits for medical and dental imaging places the responsibility solely to the health care provider to choose the appropriate imaging modality and the exposure size.

The European Guidelines of Radiation Protection and the American Dental Association state that there is no contraindication for taking a radiograph on a woman who is or may be pregnant but that it must be clinically justified.30-31 In Poland, most of the responders overestimated the risk of dental radiographic imaging of pregnant patients.12 Thirty-nine percent of Iranian dentists indicated that they would not perform periapical radiographs on pregnant women.20 In our study, 66% of oral health care providers knew that performing dental radiographic examinations in pregnant women in South Africa is not contraindicated, but risks and benefits must be evaluated. A lack of awareness may lead to neglecting radiological diagnostics for pregnant patients when the benefits out-weight the risks.12

Only 24% of oral health care workers knew the safest position for the operator during exposure with only 22% of the Dentist group providing the correct answer. The results for this finding was lower than an Australian survey which found that 87% of the participants correctly indicated that the position should be at least 2 m from the primary beam.28

However, most of the Belgian dentists (75%) always stood in the same spot in their dental office regardless of the position of the primary beam.13 In an Iranian study, only 36% of the dentists used the position and distance rule correctly.20

The regulation regarding the exemption of wearing personal monitoring badges were correctly answered by 49%. Only 30% of the respondents from the Therapist and Oral Hygienists group answered this question correctly. In the USA, 22% of oral hygienists who responded to a survey, wore dosimeter badges.32

Only 49% of responders to our study knew the amount of the full-body radiation dose limit of 1 mSv for the general public per year. Sporadic knowledge about occupational radiation safety leads to the general underestimation of the potential risks of ionizing radiation exposure.13

A limitation of this study was the limited number of respondents, particularly in the dental therapist group. Hence the results cannot be confidently compared between the dental therapy and the other groups. The number of responders in the other responder groups were, however, representative to draw valuable conclusions. The pre-programmed survey tool allowed a responder to proceed to the next question before saving the answer to the question in hand.

Therefore, the findings of this study can only be generalized into the results of the positive responses.

Finally, because the questionnaires were not completed in the company of the researchers, there was always the possibility that some responders were researching their answers on the internet or consulting their peers. Therefore, awareness reported may be overestimated.

CONCLUSIONS

The results from this study clearly indicate a need for improvement in radiation awareness among oral health care providers. The time of qualification and the participation in continues development courses had a positive influence on the results.

Emphasis should, however, be on the development of CPD courses to improve knowledge and to increase radiation awareness. However, this conclusion can only be drawn from the responders of the study and the same conclusion cannot be made for the overall awareness in South Africa.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the South African Dental Association, Oral Hygienists Association of South Africa, South African Dental Therapy Association and Dental Professionals Association of South Africa for their cooperation as well as all the oral health care providers who completed the questionnaire.

Declaration

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors.

References

1. Whaites E, Drage N, Dawson B. Essentials of Dental Radiography and Radiology London: Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier. 2013. [ Links ]

2. White SC, Pharoah MJ. Oral Radiology: Principles and Interpretation. 7th ed: Mosby. 2014. [ Links ]

3. Svenson B, Stâhlnacke K, Karlsson R, Fält A. Dentists' use of digital radiographic techniques: Part II - extraoral radiography: a questionnaire study of Swedish dentists. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. Informa UK Limited. Nov 13, 2018; 77(2): 150-7. Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00016357.2018.1525763. [ Links ]

4. Rushton VE, Horner K, Worthington HV. Screening panoramic radiology of adults in general dental practice: radiological findings. British Dental Journal [Internet]. Springer. Science and Business Media LLC; 2001 May; 190(9): 495-501. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801014 [ Links ]

5. Chalkley M, Listl S. First do no harm - The impact of financial incentives on dental X-rays. Journal of Health Economics Elsevier BV. 2018 Mar; 58: 1-9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.12.005 [ Links ]

6. Granlund C, Thilander-Klang A, Ylhan B, Lofthag-Hansen S, Ekestubbe A. Absorbed organ and effective doses from digital intra-oral and panoramic radiography applying the ICRP 103 recommendations for effective dose estimations. The British Journal of Radiology. British Institute of Radiology; 2016 Oct; 89(1066): 20151052. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20151052 [ Links ]

7. Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation, United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) 2000 Report, Volume I. United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) Reports. UN; 2000 Oct 13: Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.18356/49c437f9-en. [ Links ]

8. Republic of South Africa. National Health Act No. 61. 2003; 869. [ Links ]

9. Horner K, Islam M, Flygare L, Tsiklakis K, Whaites E. Basic principles for use of dental cone beam computed tomography: consensus guidelines of the European Academy of Dental and Maxillofacial Radiology. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology. British Institute of Radiology; 2009 May; 38(4): 187-95. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/dmfr/74941012. [ Links ]

10. European Commission. Radiation Protection No 172 Cone Beam Computer Tomography for Dental and Maxillofacial Radiology. (Evidence-Based Guidlines) Directorate-General for Energy. Directorate D - Nuclear Energy Unit D4 - Radiation Protection. Luxembourg. 2012. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2768/21874. [ Links ]

11. Svenson B, Soderfeldt B, Grondahl HG. Analysis of Dentists' Attitudes Towards Risks in Oral Radiology. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1996; 25(3): 151-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.25.3.9084264. [ Links ]

12. Furmaniak KZ, Kotodziejska MA, Szopinski KT. Radiation awareness among dentists, radiographers and students. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology. British Institute of Radiology Oct, 2016; 45(8): 20160097. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20160097. [ Links ]

13. Jacobs R, Vanderstappen M, Bogaerts R, Gijbels F. Attitude of the Belgian dentist population towards radiation protection. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology. British Institute of Radiology. Sep, 2004; 33(5): 334-9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/dmfr/22185511. [ Links ]

14. Brown J, Jacobs R, Levring Jäghagen E, Lindh C, Baksi G, Schulze D, et al. Basic training requirements for the use of dental CBCT by dentists: a position paper prepared by the European Academy of DentoMaxilloFacial Radiology. Dento-maxillofacial Radiology. British Institute of Radiology. Jan, 2014; 43(1): 20130291. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20130291. [ Links ]

15. Levetown M. Communicating With Children and Families: From Everyday Interactions to Skill in Conveying Distressing Information. Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). May 1, 2008; 121(5): e1441-60. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0565. [ Links ]

16. Oikarinen HT, Perttu AM, Mahajan HM, Ukkola LH, Tervonen OA, Jussila A-LI, et al. Parents' received and expected information about their child's radiation exposure during radiographic examinations. Pediatric Radiology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. Nov 13, 2018; 49(2): 155-61. Available from: http://x.doi.org/10.1007/s00-247-018-4300-z. [ Links ]

17. National Departement of Health. Republic of South Africa. Directorate Radiation Control unit. Code of Practice for Users of Medical X-Ray Equipment. 2015. Available from: https://sites.google.com/site/radiationcontroldoh/. [ Links ]

18. Noffke CE, Snyman AM. South African Legislation for Radiation Control in Dentistry: A Review. SADJ. 2007; 62(10): 438, 40, 42-5. Available from: https://journals.co.za/content/sada/62/10/EJC158948. [ Links ]

19. Noffke CE, Van der Linde A, Farman AG. Responsible use of cone beam computed tomography: minimising medico-legal risks: clinical. South African Dental Journal. Jul 1 2013; 68(6): 256-9. Available from: https://journals.co.za/content/sada/68/6/EJC141199. [ Links ]

20. Shahab S, Kavosi A, Nazarinia H, Mehralizadeh S, Moham-madpour M, Emami M. Compliance of Iranian dentists with safety standards of oral radiology. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology. British Institute of Radiology. Feb, 2012; 41(2): 159-64. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/dmfr/29207955. [ Links ]

21. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2018. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/. [ Links ]

22. Bhayat A, Chikte U. Human Resources for Oral Health Care in South Africa: A 2018 Update. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. MDPI AG; May 14, 2019; 16(10): 1668. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101668. [ Links ]

23. Awosan K. Knowledge of Radiation Hazards, Radiation Protection Practices and Clinical Profile of Health Workers in a Teaching Hospital in Northern Nigeria. Journal Of Clinical And Diagnostic Research. JCDR Research and Publications; 2016. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2016/20398.8394. [ Links ]

24. An S-Y, Lee K-M, Lee J-S. Korean dentists' perceptions and attitudes regarding radiation safety and protection. Dentomax-illofacial Radiology. British Institute of Radiology. Jan 31, 2018; 20170228. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20170228. [ Links ]

25. Wright B. Contemporary medico-legal dental radiology. Australian Dental Journal. Wiley; Feb 29, 2012; 57: 9-15. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01653.x. [ Links ]

26. Abdelkarim A, Jerrold L. Clinical considerations and potential liability associated with the use of ionizing radiation in orthodontics. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. Elsevier BV; Jul, 2018; 154(1): 15-25. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2018.01.005. [ Links ]

27. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements (NCRP). Radiation Protection in Dentistry. Bethesda, Md: NCRP. NCRP Report No. 145. 2003. Available from: https://ncrponline.org/publications/reports/ncrp-reports-145/. [ Links ]

28. Ihle IR, Neibling E, Albrecht K, Treston H, Sholapurkar A. Investigation of radiation- protection knowledge, attitudes, and practices of North Queensland dentists. Journal of Investigative and Clinical Dentistry. Wiley; Dec 2018; 12: e12374. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jicd.12374 [ Links ]

29. ICRP. Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP Publication 60. Ann. ICRP 21. 1990; (1-3). Available from: https://www.icrp.org/publication.asp?id=ICRP%20Publication%2060. [ Links ]

30. European Commission. Radiation Protection Report 136: European Guidelines on Radiation Protection in Dental Radiology: The Safe Use of Radiographs in Dental Practice Directorate-General for Energy and Transport; Nuclear Safety and Safeguards; Brussels; Luxembourg. 2004. Available from: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/ea20b522-883e-11e5-b8b7-01aa75ed71a1. [ Links ]

31. ADA Oral Health Topics. X-Rays. Key Points. June 3, 2018. Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/x-rays. [ Links ]

32. Lintag K, Bruhn AM, Tolle SL, Diawara N. Radiation Safety Practices of Dental Hygienists in the United States. J Dent Hyg. 2019; 93(4): 14-23. Available from:https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1042&context=dent alhygiene_fac_pubs. [ Links ]

33. Kim Y-J, Cha ES, Lee WJ. Occupational radiation procedures and doses in South Korean dentists. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. Wiley; May 5, 2016; 44(5): 476-84. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12237. [ Links ]

34. Kelaranta A, Ekholm M, Toroi P, Kortesniemi M. Radiation exposure to foetus and breasts from dental X-ray examinations: effect of lead shields. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology. British Institute of Radiology; Jan 2016; 45(1): 20150095. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20150095. [ Links ]

35. Miles DA. Radiographic Imaging for the Dental Team. 4th ed. St. Louis: Saunders. 2009. [ Links ]

36. Lurie AG. Doses, Benefits, Safety, and Risks in Oral and Maxillofacial Diagnostic Imaging. Health Physics. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health); 2019 Feb; 116(2): 163-9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/hp.0000000000001030. [ Links ]

37. ICRP. Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP Publication 26. Ann. ICRP. 1977; 1 (3). Available from: https://www.icrp.org/publication.asp?id=ICRP%20Publication%2026 [ Links ]

38. ICRP. Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP Publication 103. Ann. ICRP. 2007; 37(2-4): 1-332. Available from: https://www.icrp.org/publication.asp?id=ICRP%20Publication%20103. [ Links ]

39. Theodorakou C, Walker A, Horner K, Pauwels R, Bogaerts R, Jacobs Dds R, et al. Estimation of paediatric organ and effective doses from dental cone beam CT using anthropomorphic phantoms. The British Journal of Radiology. British Institute of Radiology; Feb 2012; 85(1010):153-60. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1259/bjr/19389412. [ Links ]

40. ICRP. Pregnancy and Medical Radiation. ICRP Publication 84. Ann. ICRP. 2000; 30 (1). Available from: https://www.icrp.org/publication.asp?id=ICRP%20Publication%2084 [ Links ]

41. Health Professions Council South Africa. Ethical Guidelines for Good Practice in the Health Care Professions. Guidelines on the Keeping of Patient Records. Booklet 9. Pretoria 2008. Available from: https://www.hpcsa.co.za/Uploads/Professio-al_Practice/Ethics_Booklet.pdf. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Piret Vilborn

Department of Oral Pathology and Oral Biology, School of Dentistry

Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

P.O. box 195, Highveldpark Postal Office, Southdowns 0123

City of Tshwane, Republic of South Africa

Email: vilborn@gmail.com

Author contributions:

1 . Piret Vilborn: Principal researcher, write up - 40%

2 . Andre Uys: Supervisor, review and revision of write-up - 30%

3 . Zarah Yakoob: Co-supervisor, review and revision of write-up - 20%

4 . Tanita Cronje: Data analyses and revision of write-up - 10%