Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.76 no.2 Johannesburg Mar. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2021/v76no2a8

ETHICS

Dentists and dental technicians - A united team or uncomfortable alliance?

LM SykesI; H BernitzII; LH BeckerIII; C BradfieldIV

IBSc, BDS, MDent, Dip Research Ethics (IRENSA); Dip ESMEA (Univ Dundee), DipOdont (Forensic Odontology), Department of Prosthodontics, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0002-2002-6238

IIBChD, Dip (Odont), MSc, PhD, Department of Oral Patholoqy and Oral Bioloqy, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0003-1361-1225

IIIBChD (Pret); HDip Dent (Wits); MchD (Pret); FCD (SA), Specialist and past consultant to the Department of Pros-thodiontics, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IVB Tech; BChD, PG Dip Dent, Registrar (Pros-thodontics) Department of Prosthodontics, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

The effective practising of dentistry requires that dentists and dental technicians work hand in hand, having mutual respect for each other, while maintaining the highest standards in each of their respective disciplines. From a limited survey of dentists and dental technicians it seems that a small portion of our profession have misinterpreted the concept of "hand in hand" to be one of gross perverse incentives, corruption, collusion and dishonesty.

This article may come as a shock to some and a revelation of what is known to be true to others. The issues discussed have generally been kept as "Dental family secrets", however, the authors believe that these practices need to be uncovered if we want to put an end to this behaviour.

BACKGROUND

The authors became aware that a dental technician's contract was terminated because she refused to carry out work that she felt was unethical. This motivated the authors to probe further into the professional relationship between dentists and dental technicians. While it must be stressed that the majority reported to have good and close working interactions, there were also a number of disquieting revelations, which are presented in this paper.

The purpose of documenting these is not to cause animosity, cast judgement, or forge any division amongst colleagues, but rather to highlight how easily the lure of financial gain can jeopardise honesty and integrity, and compromise the respectability of these professions. In an attempt to maintain objectivity, responses were sought from a range of junior and more experienced dentists and dental technicians, working in both the private and public sectors.

Dental technicians

Dental technicians were asked to respond to the following questions:

"Have you ever been requested by a dentist to:

a). Perform work on bad impressions, or seen evidence of poor clinical work?

b). Carry out procedures that you were unhappy to do?

c). Charge for work not done, or requested to issue fraudulent laboratory accounts?

d). If so, how did you handle the situation?"

Once their laughter had subsided they were more than willing to share their experiences. Their comments are presented verbatim.

Their response to questions a) and b) is reflected in Addendum A.

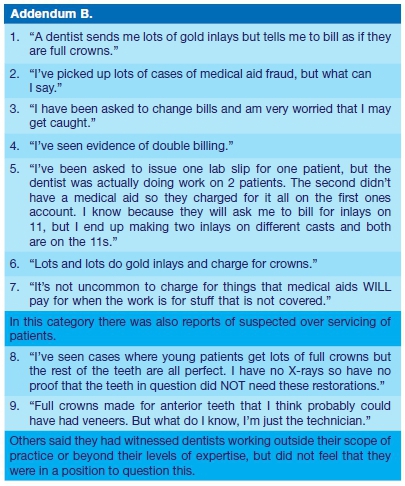

Responses to question c) revolved around issues of fraud. Their responses are reflected in Addendum B.

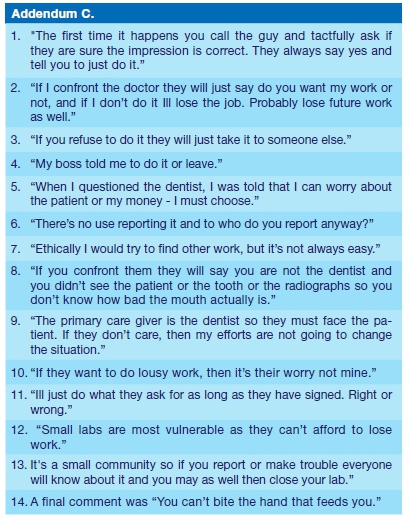

When asked, part d), how they would handle the situation, their response was as reflected in Addendum C.

). Kickbacks

This relates to payment to the dentist by the dental technician in return for having the work referred. The going rate was between 10 and 25% paid back to the dentist for each prescription received. In general amounts were lower (10-15%) for removable dentures and appliances and up to 20-25% for crown and bridge work, and im-plantology.

The money is usually paid in cash at the end of the month to the dentist. This has led to technicians using cheaper materials or over charging on certain codes to make up for paying these bribes. Items such as 9748, 9741, 9742 (cost of non-precious alloy; chrome cobalt casting alloy and specialized chrome cobalt casting alloy respectively) were often charged twice or three times.

Other examples cited were the use of cheaper/poor quality denture teeth. Instead of using the high grade 3-layered teeth, cheaper and less durable 1 and 2 layered teeth are used while still billing for the more expensive forms. Instead of using the correct Para-Post components, even though this system had been used in the impressions, some fabricate posts and cores for crown and bridge work from Duracast.

). Cash payments

This sometimes occurs in cases of dentists who have registered laboratories. The technician will perform a service and charge the dentist a certain agreed on (reduced) fee, which is paid in cash. Thus there is no record of names, invoices or receipts. The dentist will then claim the full laboratory fee from the medical aid or patient as if the procedure had been done by themselves.

). Purchasing machinery

A technician may purchase equipment such as an intraoral scanner and make it available to their clients, with the understanding that a certain number of crowns will be done per month.

This can lead to gross over servicing and patient abuse as well as disputes if the promises are not fulfilled (as would be the case with practice restriction due to the Covid-19 lockdown). In addition, with the new technology and use of scanning and digital processing, there is no longer a need to cast models or carry out disinfecting procedures, yet some technicians still charge for this despite it not having been being done.

). Paying kickbacks and declaring them as business expenses.

Technicians offer to pay for a wide range of the dentist's expenses (for example petrol and diesel, new car tyres, municipal fees), and in return the dentist will support them with provision of work.

The technician then uses these account payments as if they were their own and declares them as business expenses. Taking clients on hunting trips or paying for vacations is another common occurrence.

). Manipulating codes to bypass medical aid restrictions

Procedures not covered by medical aids may be carried out (full gold crown) yet charged for as one that is covered (porcelain crown). Despite the obvious fraud, this can also have other serious legal consequences such as in cases of unnatural death where dental identification is needed (see ethics paper SADJ June 2020).1

DISCUSSION

Based on the Dental Technicians' responses it seems that they, when requested to complete work on poor impressions, or are faced with other difficult ethical dilemmas, generally have one of four options:

1). Talk to the dentist and if no compromise is reached, risk losing his/her work.

2). Accept the situation and just try and make the best of the task at hand for the sake of the patient and his/her livelihood.

3). Take it upon themselves to adapt or alter the case details before working on it. This may involve adjusting midlines, smile lines, arch forms and occlusal planes in dentures, inserting post dams by "guesti-mation" onto final casts, ditching around and removing plaster from casts where the impressions were poor, to even altering the actual tooth preparations on the cast in fixed prosthodontics.

4). Commit fraud by charging for work other than that actually performed.

The option of reporting the dentist to the HPCSA or the relevant Medical Aid Societies was never even considered by any of them.

It also raises a number of questions for the dental profession regarding professional education and training. Why do students need five years of training if they are not going to perform the procedures, as they have been taught, once in private practice? How can teaching be improved to ensure students understand the rationale behind, and the relevance of many clinical procedures? Is the teaching in ethics underscored in the clinical wards by the attitude and guidance of teachers, addressing practical situations, or is it too theoretical in nature?

The final assessment on whether the proposed and actual treatment meet the clinical requirements rests with the dentist. The dentist is the guardian, on whom the patient relies for protection of his/her interests. It requires that dentists meet the demands of morality (a personal compass of right and wrong), of ethics (the rules of conduct pertaining to the profession) and of the law (a basic, enforceable standard of behaviour)

Ethics and the legal prescriptions can be taught, but morality is a personal trait. The late Professor Chris Snijman referred to it as "something you get in with your mother's milk"

Prospective dental students are admitted to the undergraduate course based on school leaving results. They are not evaluated for their approach to "ubuntu," nor in respect of their manual dexterity. The outcome of this is that individuals, who do not have the underlying personal characteristics and/or physical abilities to meet the demands of the profession in terms of either/or conduct and/or clinical performance, may be admitted to the study of dentistry. It is then required from their tutors to manage these shortcomings, resulting in them having to spend more time with these students in the clinical wards, to the detriment of others.

Equally, the practice of dentists and technicians demanding or offering kickbacks is illegal, unethical, and brings both parties into disrepute. The Health Profession Council Guidelines for Good Practice are very clear on all of these issues.

HPCSA Booklet 2 deals with Fees and Commissions and talks to the issue of accepting kickbacks. Rule 7. (1) states: A practitioner shall not accept commission or any material consideration, (monetary or otherwise) from a person or from another practitioner or institution in return for the purchase, sale or supply of any goods, substances or materials used by him or her in the conduct of his or her professional practice; and 7.(3) A practitioner shall not offer or accept any payment, benefit or material consideration (monetary or otherwise) which is calculated to induce him or her to act or not to act in a particular way not scientifically, professionally or medically indicated or to under-service, over-service or over-charge patients.2

Furthermore Booklet 11 cautions against accepting commission in return for services. In terms of Rule 7(3.9.1) Health care practitioners shall not accept commission or any financial gain or other valuable consideration from any person or body or service in return for the purchase, sale or supply of any goods, substances or materials used by the health care professional in his or her practice.3

HPCSA Booklet 11 addresses issues related to the overuse of technology. Whether the dentist is the owner, or user of expensive technology made available by another party, professional ethics dictate that the treatment prescription be based on the diagnosis and the professionally accepted treatment.

CAD/CAM restorations made in order to meet an agreed-upon quantity, is clearly over servicing. HPCSA Rule 7. (3.1.1) states: Health care practitioners shall not provide a service or perform or direct certain procedures to be performed on a patient that are neither indicated nor scientific or have been shown to be ineffective, harmful or inappropriate through evidence-based review.3

The rule also cautions against preferential use of specific services, if the dentist stands to benefit financially from it, like having an exclusive agreement with one particular dental laboratory, Rule 7. (3.4) reads: Health care practitioners shall not engage in or advocate the preferential use of any health establishment or medical device or health related service if any financial gain or other valuable consideration is derived from such preferential usage by the health care professional.3

With such clear guidelines it is surprising that both dentists and technicians continue to embark in these illicit practices. Considering that both parties are complicit, the question arises as to who should be penalised if the fraud is discovered?

A further concern is that the dishonesty of one party will by association compromise the integrity of the other if they agree to take part in the scheme. Are we thus turning each other into "offenders and lawbreakers"?

CONCLUSION

The dental fraternity appears to be on a very slippery slope with widespread abuse of authority, blatant disregard for ethical principles, and too many instances of financial dishonesty between and amongst colleagues from two of the closest disciplines. If team members no longer respect each other, are happy to defraud their patients and the medical schemes, and blatantly disregard the law, then what does this say about us as professionals? How can we ever expect our patients and the general public to look up to us, to respect us, or to trust us with their oral health?

We cannot hide behind excuses such as "Everyone else is doing it, so I have no choice but to do the same" or "The medical aids have pushed us into this and we now have to do what we have to do to survive". The onus is on each person to strive to maintain the highest standards of honesty, integrity, and accountability that we all pledged to honour when we took the Hippocratic oath.4

Has the time not come for re-assessing admission criteria so that attitude and dexterity can be evaluated before admission to the course in dentistry? Should we not be assessing the course content so that emphasis can be placed on training in clinical procedures that patients can expect dentists to be able to perform?

While not making excuses for unethical behaviour, it must be noted that the impact of the 4th industrial revolution has not only changed the face of dentistry and dental technology, but also the relationship between both parties. Digital technology has resulted in a blurring of boundaries between the clinical and laboratory aspects of many restorative procedures. Now dentists are carrying out work that was previously within the scope of technicians. Perhaps the next paper should investigate issues such as who can bill for what procedures? How much can each party charge? What codes should be used for medical aid purposes? And who carries the final responsibility for the fit and aesthetics at delivery.

References

1. Sykes LM, Bernitz H, Robertson L. Fraudulent records - Grave Forensic consequences. SADJ, June 2020, Vol. 75, No. 5. 2020; 272-4 [ Links ]

2. Health Professions Council of South Africa. Guidelines for Good Practice in the Health Care Professions. Booklet 2. Accessed at: http://www.hpcsa.co.za; Accessed on 06-072020. [ Links ]

3. Health Professions Council of South Africa. Guidelines for Good clinical practice in the Health Care Professions. Booklet 11. Accessed at: http://www.hpcsa.co.za; Accessed on 0607-2020. [ Links ]

4. The Hippocratic Oath. Medical Definition of Hippocratic oath - MedicineNet. Accessed at: www.medicinenet.com>script>-main>art; accessed on: 01-07-2020. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Leanne M Sykes

Department of Prosthodontics, School of Dentistry

Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria

South Africa

Email: leanne.sykes@up.ac.za

Author contributions:

1 . Leanne M Sykes: Primary author - 35%

2 . Herman Bernitz: Second author - 35%

3 . Len Becker: Third author - 20%

4 . C Bradfield: Fourth author - 10%