Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562

Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.75 n.4 Johannesburg May. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2020/v75no4a10

ETHICS

LM SykesI; E CraffordII; A FortuinIII

IBSc, BDS, MDent, IRENSA, Dip Forensic Path, Dip ESMEA, Head of Department of Prosthodontics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0002-2002-6238

IIBBChD, BChD Hons, Oral Medicine, MChD OMP, Senior Specialist Department of Oral Medicine and Periodontics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

IIIBChD, PDD, MDent, Specialist Department of Prosthodontics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

Quality dental care begins with determining the patient's understanding of the dental treatment, their expectations, attaining all the diagnostic information and compiling a treatment plan best suited to each individual.1 Once a decision has been made to undertake treatment, the clinician may adopt a paternalistic approach or could lean towards respecting patient autonomy.2

In the former, the clinician takes on an authoritative role and imposes the treatment plan on the patient, while in the latter there is more emphasis on the doctor:patient relationship and it is the patient who ultimately decides on what treatment will be performed. If there is a lack of agreement between the two, the practitioner may be faced with a legal and/or ethical dilemma.2

In legal terms, paternalism has been defined as "Restriction of a subjects self-regarding conduct primarily for the good of that same subject".3 However many disputes have arisen over its use and justification in the health care setting.

Confusion and disagreement has been compounded by the fact that there are no clear boundaries between what should be considered "soft" (weak) paternalism, and what constitutes "hard" (strong) paternalism. Soft paternalism can be justified on the basis that the individual "lacks the requisite decision-making capacity to engage in the restricted conduct". This includes situations where their decision was: "not factually informed; not adequately understood; coerced; or not substantially voluntary".

Maturity and mental capacity have also been mentioned as factors to consider. Soft paternalism does not call for the constraint of any decision, but rather for the constraint of an "impaired decision" due to a person's "compulsion, misinformation, impetousness, clouded judgement, immaturity, or defective faculties of reasoning", and is meant to protect that subject from dangerous choices that are not truly their own.1 It is often not regarded as truly paternalistic if the agent's liberty-limiting actions are performed to either protect the subject from harm, or from receiving no benefits, or to confirm that their decisions were truly voluntary. Note that agents' motives matter!

Hard paternalism often includes politically, morally, or ethically controversial issues such as government legislation regarding wearing of seat belts, prohibition of recreational drugs or water fluoridation.4

When deciding if it is liberty-limiting one has to consider whether it is justified and to what extent. Pope (2004)3 proposed that an action may be regarded as justifiable hard paternalism if the agent's liberty-limiting intervention met four criteria: the agent must:

1. intentionally limit the subject's liberty;

2. believe their actions will contribute to the subject's welfare and must intervene with a benevolent motive either to confer a benefit or to prevent the subject from harm;

3. show benevolence independent of the subject's preferences; and

4. disregard the fact that the subject's actions are voluntary, or deliberately limits their voluntary conduct.

To further distinguish between hard paternalism and tyrannical dictatorship, the liberty-limiting action of the clinician must be "subject focused", altruistic, benevolent and aim to confer benefit or avert harm.3 Note, that he states it must be "benevolent" not necessarily "beneficent". Once again it is a matter of intent. The former refers to the agent's will (volens) to do good (bene), while the latter refers to the actual action of doing (facere) good (bene).

In medical terms, paternalism refers to "acting without consent or overriding a persons wishes, wants or actions, in order to benefit the patient or prevent harm to them".3 Strong paternalism is when the clinician overrides competent patient's wishes and is rejected as it violates their autonomy and falsely presumes knowing what is best for them.3 Weak paternalism refers to acting for the benefit of an incompetent patient and may be justified in order to restore their competence, or to prevent them from harm, and as such may be justified.5

At the same, it is a social, political, and moral obligation to respect an individual's autonomy and self-determination. Proponents of this right argue that the beneficence of paternalism may be at the expense of autonomy, however they often fail to consider the benevolence of the action. It is also situation specific, and open to change. A clinician's opinions and subsequent actions could vary depending on the circumstances at that time. The important issue to consider is the intention that guided their judgment and decision. This was clearly illustrated by results of one survey question described below.

SURVEY DESIGN

In the same survey as was reported on in the ethics paper of April 20206, dental practitioners were asked to complete a questionnaire in which a number of practice-related ethical scenarios and questions were posed. One question related to patient autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, paternalism, and informed consent.

A case scenario was presented in four parts with additional information given progressively in order to see if and how the respondents' opinions changed depending on the circumstances. Over 40 dentists completed the questionnaire, and the results are presented below.

RESULTS

The case read as follows: "A young attractive lady comes to your rooms and asks you to place veneers on all her anterior teeth in order to give her a bright, A1 smile.

All of her teeth are sound, and in your opinion she already has an attractive and natural looking smile. You educate her as to all the risks involved in the procedure but she is still adamant that she wants to go ahead with the treatment."

a). In terms of respect for patient autonomy, would you concede to treat?

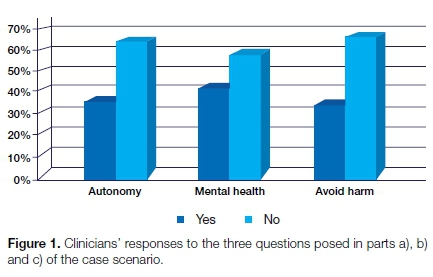

Only 35% of the respondents said they would treat, (Figure 1) some having added provisos such as: "I would only treat if full consent had been given and if I know I can do the work well". Sixty five percent said they would not treat with many stating that they would advise her to seek a second opinion.

b). The WHO defines health as "a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely an absence of disease or infirmity". With this in mind, if the patient pleaded that she was experiencing emotional and psychological distress as a result of being self-conscious, that she understood all the risks, and was willing to take full responsibility, would you then agree to treat her?

Only 6% more dentists (41%) now agreed to treat despite the added psychological perspective (Figure 1 ). There was concern that the patient needed psychological rather than dental intervention, which made some even more reluctant to treat her.

I am not a trained psychologist but would be alert to issues of body dysmorphia and suggest pre-counselling.

I would have to consider the risks of acquiescing to treatment demands being made in that context.

She must seek other help, this is not an emergency.

No, this is intrinsically wrong.

In that case I would whiten them for her only.

c). Ethical behaviour refers not only to the act of doing good (beneficence), but also to the duty of preventing harm. If she now said that she knew of a technician who was willing to carry out the work for her. You were concerned that this person was not a trained clinician, and may provide a poor service. Would you then concede to treat in order to prevent possible harm?

Opinions did not change despite the added information to consider the risks of harm. Thirty three percent agreed to treat and 67% refused (Figure 1).

Further comments were received when asked to elaborate on any of the above questions. Many advised to get a second opinion from another dentist. Other comments included:

As a health care practitioner I have a duty and responsibility not to do harm. If "it is not broken, why fix it" - we are also educators if there is no need for treatment do not force it.

I'll strongly advise a second opinion and get her to sign that this was not life threatening or an emergency and so didn't need me to treat her at that time.

Regardless of her arguments, if I think it's a clinically incorrect decision I still will not treat. Healthy enamel cannot be bought - for everything else there is MasterCard (sic).

I believe in a healthy mouth preservation and my duty to inform patients

The patient is informed of what her rights are and what the role of the dentist/and other professionals is

As long as you have informed her and made a document of all discussions, you can let her make her own decision

I would rather discuss all the aspects of tooth bleaching.

Those whose opinion was altered by her final argument gave reasons such as:

Yes, in this case if it's the patient's choice and her wish, I'd rather she gets professional treatment by me than someone else.

The patient would be educated by me and the scope of practice of a technician and advised to get another dental opinion or psychological counselling, however, if she chose to persist in spite of being provided all pertinent information this would be a case of her exercising her autonomy and she can do it.

Help her to prevent her suffering from future harm.

A few had strong opinions that were not swayed by the final argument:

I said no as this case is a disaster waiting to happen. There is also a time to say NO. Definitely not.

There are many dentists around and the patient will move on.

This type of patient is a danger to the practice.

Unfortunately I don't like being forced into doing something so NO!

The last question related to the issue of paternalism, and whether this is ever justified in a health care setting.

d). Would you as an educated health care provider, feel justified to take a paternalistic approach and refuse treatment based on your opinion that the procedure was both unnecessary and destructive?

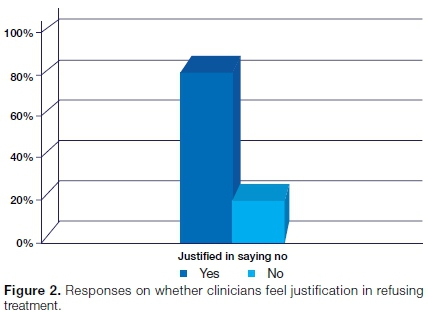

The majority (83%) felt justified that they could refuse treatment based on their training and judgement (Figure 2), and justified their decision with comments such as:

Sound clinical rationale is not paternalistic and does not conflict with patient autonomy.

DISCUSSION

Traditionally in medicine and dentistry, the clinician, being the trained professional, was presumed to know what was the best for their patients, and thus justified in making treatment decision for them.

Proponents of outside agent intervention argued that the choices individuals make do not always reflect their true desires and preferences, and are often not in their own best interest. Carl Elliot went so far as to state that "People do not always mean what they say; they do not always say what they want; and they do not always want what they say they want".7 This radical opinion may have led others to question the ethics of hard paternalism, and the subsequent development of a more patient-centred approach.

Beauchamp and Childress were leaders in the field of biomedical ethics when they published their "Principles of Biomedical Ethics".8 Since then there has been growing emphasis on the principles surrounding respect for patients' autonomy.3 This holds that individuals have the right to make their own choices, and develop their own life plan. In the health care setting it translates into informed consent, and requires a clinician to provide all necessary information for patients to make a free, intelligent decision; ensure they understand the information; and to recommend an ideal treatment option without persuasion, pressure or coercion.5

They strongly supported the notion that "The core of any clinical encounter in a health care setting is respect for patients' autonomy, and their right to chose or decline a recommendation without intimidation or pressure, and should be able to make decisions for themselves free from controlling interference or influence".8

Others have added that "respecting patients' autonomy yields satisfaction for that person directly, while interfering with their autonomy may be experienced as a form of pain and suffering. Furthermore, when people who are capable of making autonomous choices are allowed to do so, their maximal well-being will almost always be more efficiently produced than if someone else chooses instead".9

Many other authors have added to the literature on "patient-centeredness", and the need to ensure that the treatment plan is tailored to incorporate options for a patient with respect to their individuality, values, ethnicity and social endowments.10 It has been postulated that this type of communication would lead to better acceptance of treatment plans and improved interactions between patients and clinicians.10

The patient-centred model further evolved to the shared decision-making approach which entails the compilation of several viable treatment options for a specific problem, presentation of the disadvantages and advantages of each, and allowing the patient to choose which suited them the most.11

This stratagem aims to bridge the gap between paternalism and patient autonomy due to the nurturing of a mutual trust between the opinion of the clinician and the decision-making process of the patient.11 It also leads to complete informed consent by enhancing the patient's understanding and knowledge of each of the options and how each could address their specific problems.12

However, care should be taken to not indulge and over-express information pertaining to a specific treatment option that the clinician prefers. This practice has been termed "nudging" and will inevitably lead to a libertarian paternalism wherein the patient tends to make "the popular decision".12

While these authors do concede that patient education is a prerequisite to decision making9, the overarching sentiment is that autonomy is sacrosanct and dentists should not assume an "unwarranted degree of authority over their patients".13 This has led to the concept of paternalism becoming frowned upon and even regarded as taboo by some medical professionals.

Dworkin (1988) considered paternalism as "interference with a person's liberty of action justified by reason referring exclusively to the welfare of the person being coerced".14 He further argued that it prevented people from doing what they had decided, interfered with how they arrived at their decisions, or attempted to substitute one's own judgement for theirs, in order to promote their welfare.

His concern was that this presumption of being right and thus justified in trying to override the other person's judgement denied them the opportunity to choose their own actions and treated them as "less than moral equals".13,14

Where then does this leave the trained dental clinicians who do not agree with their patient's demands or desires? Even soft paternalism does not allow them to impose their views, as the patients in question are generally not considered to be incompetent. Thus, regardless of whether their judgment is based on moral principles or educated discretion, do they have the right (and courage) to disregard the patient's autonomy, and refuse to treat?

In the above survey it was evident that most dentists held onto their original treatment decisions regardless of the added issues presented in the subsequent questions. In fact slightly more refused to treat when they sensed they were being pressurised or manipulated by the patient (67% vs. 65%). The overwhelming majority (83%) felt justified to take a paternalistic approach and not treat based on their moral principles or diagnostic reasoning.

How then do they justify a paternalistic decision centred on their personal ethical views, experience, training, clinical judgement, and desire to promote beneficence/non-maleficence, especially if this goes against the principles of respect for patient autonomy? There is no clear and simple answer. However, a practitioner needs to recognise that there are "limits on what each person can do and that many treatment options are mixed, containing both chance of benefit and risk of harm".5 So yes, sometimes this does mean they can take a paternalistic approach and be justified in saying no!

CONCLUSION

Paternalism has been both "defended and attacked in clinical medicine, public health, health policy and the law".15 It is no longer clear when, if and which types are justified in clinical practice. Perhaps the best advice is to "always consider the patient's best interest, do those acts that do more good than harm, not do those that could cause harm, and constantly maintain the highest standards of care".5

References

1. Goldstein RE. Esthetics in Dentistry (2nd Edition: Volume 1). 1998; Canada: B Decker. [ Links ]

2. Lepping P, Palmstierna T, Raveesh BN (2016). Paternalism v. autonomy - are we barking up the wrong tree? The British Journal of Psychiatry 2016; 209: 95-6. doi: 10.1192/bjp. bp.116.181032. [ Links ]

3. Pope TM. Counting the dragon's teeth and claws. Georgia State University Law Review. 2004; 23(4): 659-700. [ Links ]

4. Beauchamp, TL. (1981). Paternalism and Refusals to sterilize, in Rights and responsibilities in modern medicine. Ed. Marc D Basson. 1981; 137: 142 [ Links ]

5. Beauchamp, TL, and Childress, J. The principles of bio-medical ethics, 4th ed. Weak paternalism, acting for the benefit of an incompetent patient. 2000; Accessed at: www.utcomchatt.org>docs>biomedics. On 27-03-2020. [ Links ]

6. Sykes, LM, Crafford, E, and Bradfield, C. From Pandemic, to Panic to "Pendemic". SADJ. 2020; 75(3): 157-9. [ Links ]

7. Elliot, C. Meaning what you say. J Clinical Ethics. 1993; 61: 61. [ Links ]

8. Beauchamp TL, and Childress JF. In (eds): Principles of Bio-medical Ethics, 5th ed. New York City: Oxford University Press. 57-103. [ Links ]

9. Ozar, DT, and Sokol, DJ (2002): The relationship between patient and professional. In (eds): Dental Ethics at Chairside: Professional Principles and Practical Applications, 2nd ed. Washington: Georgetown University Press. 2002; 49. [ Links ]

10. Valerie Carrard, Marianne Schmid Mast & Gaëtan Cousin. Beyond. 2016. [ Links ]

11. "One Size Fits All": Physician Nonverbal Adaptability to Patients' Need for Paternalism and Its Positive Consultation Outcomes, Health Communication. 2015; 31(11), 1327-33, DOI:10.1080/10410236.2015.1052871. [ Links ]

12. Lewis, J. Does shared decision making respect a patient's relational autonomy? J Eval Clin Pract. 2019; 25: 1063-9. [ Links ]

13. Simkulet, W. Informed consent and nudging. Bioethics. 2019; 33: 169-84. [ Links ]

14. Reid, KI. Respect for patients' autonomy. JADA. 2009 140; 470-4. [ Links ]

15. Dworkin, G. The Theory and Practice of Autonomy. Cambridge, England. Cambridge University Press. 1988; 121. [ Links ]

16. Beauchamp, TL. The Concept of Paternalism in Biomedical Ethics. 2009; Accessed at: www.degruyter.com>jfwe.2009.14.issue-1>9783110208856.77xml. Accessed on 27-03-2020. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Leanne M Sykes

Head of Department of Prosthodontics, University of Pretoria

Pretoria, South Africa

Email: leanne.sykes@up.ac.za

Author contributions:

1 . Leanne M Sykes: Principal author - 60%

2 . Elmine Crafford: Second author - 20%

3 . Alwyn Fortuin: Third author - 20%