Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.75 no.3 Johannesburg Abr. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2020/v75no3a6

CASE REPORT

Forensic case book: Mirror image ' selfie' causes confusion

L RobinsonI; MA MakhobaII; H BernitzIII

IBChD, PDD (Maxillofacial Radiology), PDD (Forensic Odontology), Department of Oral Pathology and Oral Biology, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria. ORCID Number: 0000-0002-0549-7824

IIMBChB, FC For Path (SA), Dip For Med (Path), Department of Forensic Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria. ORCID Number: 0000-0003-0684-0003

IIIBChD, Dip (Odont), MSc, PhD., Department of Oral Pathology and Oral Biology, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria. ORCID Number: 0000-0003-1361-1225

CASE REPORT

The body of a decomposed female was found immersed in a water purification plant in a small town. The South African Police Service (SAPS) believed that the body could be that of a person they had been searching for since the missing person report was filed.

Following an autopsy by a forensic pathologist, the forensic odontology team at the University of Pretoria was requested to review the case, as the deceased was noted to have had dental treatment. The warrant officer involved in the case was able to supply two photographs ('selfies') as the only ante-mortem records.

Intra-oral radiographs and digital photographs were taken of the maxillary and mandibular dental arches (Figures 1-2).

Full dental charting with the completion of an odonto-gram was carried out on the said remains (Figure 3). The ante-mortem photographs (selfies) were compared to the post-mortem dental remains.

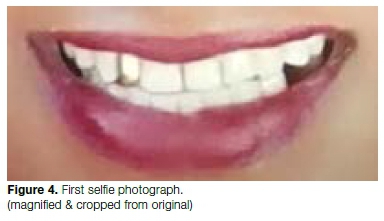

At initial inspection of the first selfie photograph (Figure 4), a mismatch was declared. Examination of the second selfie photograph (Figure 5) was more promising, as the gold inlay appeared to correspond with the post-mortem dental remains.

However, the presence of a gold inlay was not considered unique, as this is a relatively common dental finding in the community.

Unfortunately, the second selfie photograph showed no mandibular teeth. At this stage it was noted that the first of the selfies was in fact a mirror image of the victim (Figure 6). Realising this, it was concluded that both selfie photographs were of the same individual, and all identified dental features from the photographs could be compared with the post-mortem dental remains.

The following points of dental concordance were noted during the examination:

1. The right mandibular second premolar was missing ante-mortem.

2. The left maxillary lateral incisor had a gold inlay.

3. The crowns of the left maxillary central incisor had similar characteristic shapes.

4. The crowns of the right maxillary central incisor had similar highly characteristic shapes (the tooth had been dentally prepared for some sort of inlay, giving it a mesial and distal parallel appearance).

5. The incisal edge of the right maxillary lateral incisor was concave and shorter than the right central incisor and canine.

In summary, the presence of multiple identifiable dental features and no unexplained discrepancies when comparing the ante-mortem photographs (selfies) and the post-mortem dental records, it could be confirmed with absolute certainty that the body was indeed that of the reported missing person.

In the South African context, selfies are an important tool in identifying unknown bodies, as a large portion of the population does not have access to modern dentistry, but many have smartphones to take selfies.

DISCUSSION

Forensic odontology, as with other methods of identification, involves comparing ante-mortem (AM) data with post-mortem (PM) findings.1-2 The advantage of teeth as a source of identification lies in their ability to withstand significant environmental influences.3 The success of dental human identification relies on the availability of AM data3, emphasising the importance of thorough record keeping with regards to dental charting, procedures performed, plaster models and radiographs.2

In some instances AM dental data may not be available for various reasons, such as immigrants without clinical histories, patients without restorative dental treatment due to efficient preventative dentistry or no access to a dentist, and cases where the patient's dentist is unknown to their family.1

In the absence of dental records, photographs can play an important role in aiding identification. If the individual's anterior teeth are clearly visible in an AM photograph, then individual dental attributes can be compared and matched to PM photographs.

These key characteristics include the shape of the crowns, morphological characteristics, dental anomalies, size, width, outline, distances and alignment, facial profile and the presence of any recognisable fixed prosthetics.1,4

Technological advances allow for image manipulation, creating useful forensic techniques for the interpretation of smile photographs. Digital images allow for easy flipping, creating a mirrored image. Commonly applied techniques with scientific validation include direct comparison of morphological dental traits, dental super-imposition, and the analysis of the incisal contours of anterior teeth.2

With the advent of smartphones and social networks, there has been a growing trend towards so-called "selfie" photographs. The Oxford English Dictionary designated selfie as the International Word of the Year in 2013 and defined the term as "a photo of yourself that you take, typically with a smartphone or a webcam, and usually put on a social networking site."1

A selfie is usually taken with an extended arm or a supporting rod, thus the face and smile frequently appear in the photo. In a study of photographs of 1000 individuals, 76.7% showed a smile that could be of value in the identification process.5

There has also been a rapid growth in the development of applications for smartphones used to And and locate missing persons. One such application, appropriately named Selfie Forensic ID, employs selfie and face photographs to create a social networking archive of dental data, including the dental features of anterior teeth and smiles of registered individuals.4

Photographic analysis for identification purposes has the advantages of low cost, rapid speed and high reliability.2 However, this method does not come without its disadvantages, including a limited number of visible teeth in the photograph, low image quality and the possibility of morphological changes in the teeth since the AM photo was taken. An AM photograph is crucial when taking PM photographs, as the angulation of the photograph must be reproduced in the X, Y and Z (depth) axes for accurate comparison.1

CONCLUSION

This case report highlights the importance of selfie photographs in the identification of unidentified bodies. New methods of identification in forensic odontology should be pursued in order to accommodate technological evolution, particularly in the absence of traditional methods of comparison, such as dental records and radiographs.

References

1. Miranda GE, Freitas SG, Maia LVA, Melani RFH. An unusual method of forensic human identification: Use of selfie photographs. Forensic Sci Int. 2016; 263: 14-7. [ Links ]

2. Silva RF, Franco A, Souza JB, Picoli FF, Mendes SD, Nunes FG. Human identification through the analysis of smile photographs. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2015; 36(2): 71-4. [ Links ]

3. Silva RF, Felter M, Tolentino PHMP, Rodrigues LG, Andrade MGBA, Franco A. Forensic importance of intraoral photographs for human identification in dental autopsies: A case report. Bioscience. 2017; 33(6): 1696-700. [ Links ]

4. Nuzzolese E, Lupariello F, Di Vella G. Selfie identification app as a forensic tool for missing and unidentified persons. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2018; 10(2): 75-8. [ Links ]

5. McKenna JJI. A qualitative and quantitative analysis of the anterior dentition visible in photographs and its application to forensic odontology. Master's Thesis. University of Hong Kong; 1986. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Herman Bernitz

Department of Oral Pathology and Oral Biology

University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Tel. no.: +27 (0)12 319 2320

Fax no.: +27 (0)12 321 2225

Email: bernitz@iafrica.com

Author contributions:

1 . Liam Robinson: Primary author - 50%

2 . Musa A Makhoba: Case information - 10%

3 . Herman Bernitz: Secondary author & advisor - 40%