Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Dental Journal

versión On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versión impresa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.75 no.1 Johannesburg feb. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2020/v75no1a1

RESEARCH

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2020/v75no1a1

Self-reported oral hygiene practices and oral health status among dental professionals

SR HabibI; AK AlotaibiII; MA AlabdulkaderIII; SM AlanaziIV; MS AhmedaniV

IBDS, FCPS, Associate Professor, Department of Prosthetic Dental Sciences, College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. ORCID Number: 0000-0002-4398-3479

IIBDS, Staff Dentist, King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

IIIBDS, Staff Dentist, King Abdulaziz Hospital, Al Ahsa, Saudi Arabia

IVBDS, Staff Dentist, Primary Care Clinic, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

VB.Sc.Hons., M.Sc.Hons., Ph.D., DHS, Assistant Professor, Department of Periodontics and Community Dentistry, College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

ABSTRACT

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES: The aim of this study was to evaluate the oral hygiene practices and oral status of dental professionals working in Riyadh, KSA.

METHODS: Questionnaires were distributed to a conveniently se-ected sample of 400 dental professionals. The questionnaire included the demographics, oral-hygiene practices, past-dental history, self-reported current-dental status, dental appointments, self-reported family-dental condition, self-grading of oral-health and possible reasons for negligence in oral health.

RESULTS: The response rate was 68.8%. Significant differences between male and female participants were observed regarding the reported frequencies of brushing (p=.001) and the history of dental visits (p = .013).

Differences between the responses to the social habits on the consumption of coffee, tea, soft drinks, cigarettes and water pipe were insignificant. Generally, the participant's experiences with dental treatment was excellent to very good. Avoiding dental visits due to a fear of cross infection was very high (Likert scale = 3.47 out of 4) among participants.

CONCLUSIONS: Participating dental professionals, oral hygiene practices and oral health status were satisfactory. Gender-based differences were found with females expressing more care regarding their oral health. Gingival bleeding/gingivitis and bruxism were prevalent among the male and female participants respectively. Poor oral hygiene was the primary cause for the damaged dentition. Fear of cross infection from the dental treatment prevented the participants for seeking dental treatment.

Keywords: Oral health attitude; Oral health behavior; Oral Hygiene Practices; Dental Professionals; Oral hygiene.

INTRODUCTION

Oral health is an integral part of an individual's general health. Disease-free oral cavities and healthy tooth-supporting tissues are essential for optimum oral functionality. Interplay of various factors affect the socioeconomic status, education and availability of health care facilities which are significant factors that greatly influence oral health.1

Dental caries, gingival inflammation and eventual tooth loss requiring artificial tooth replacement are deleterious consequences of oral hygiene neglect. The majority of people believe that loss is inevitable, which eventually needs replacement; also contributing towards the negligence of maintaining good oral hygiene.

Neglect in oral hygiene massively affects the quality of life and expectancy.2 Oral diseases as a result of poor oral hygiene may lead to the manifestation of various systemic diseases. Various studies have investigated the relation of oral cavity and its microbiology to several other organ systems. This reflects how important it is to maintain good oral hygiene.3

Education plays a major role in guiding people regarding their oral hygiene. Individuals at higher education levels show more responsibility towards eating habits and performing necessary oral hygiene routines.4 They are more aware of the consequences and problems caused by neglect in oral hygiene.

Dental health education can help improve individual, group and community well-being. Education tends to shape behavioural patterns which begin with change in attitude and transformation in conduct.5,6 Health care sector needs to invest more towards increasing awareness and helping educate individuals about oral hygiene measures.7 Oral hygiene education should be promoted alongside medical health since both are intertwined.8

General awareness for maintaining oral health is either acquired through dental check-ups and appointments. The majority of people don't routinely visit dentists unless one experiences dental pain. Visiting dentists is considered unnecessary and may be because people are unaware of the consequences of neglecting their oral health. Prevention is better than cure but only few out of thousands believe so.9,10

Dental professionals are extensively trained regarding the importance and maintenance of good oral hygiene. They are well aware of the consequences oral health disease due to compromises in oral hygiene measures and they can effectively deliver these guidelines to patients over time.11 Dental professionals become oral health providers who need to address key oral health issues in their communities. Dental professionals are aware of oral hygiene habits and their practices reflect their dedication towards health care.

In order to be able to deliver great care and perform dental health duties for preventing and treating oral diseases, they should also be monitoring their own oral hygiene levels. They should have an increased responsibility to maintain oral hygiene measures themselves and advise patients accordingly.12 A dentist is required to advise on and to address oral hygiene measures, but it is important for them to realize how important it is to evaluate their personal dental hygiene status on a regular basis.

The reason why dental professionals should strictly observe and adopt optimal oral hygiene practices is that emphasis on the oral health during clinical procedures are part of the integral routine of their work.13 When they set good standards of oral health care for themselves oral healthcare practitioners would in all probability deliver optimum care to their patients. Moreover, oral health professionals are also responsible for imparting dental education to their students and respective institutes. They are mentors of dental students which are the future of the oral health sector. Any negligence in their conduct not only affects students but also the patients.12,14

Some studies concluded the lack of adequate dental health practises amongst the dental professionals exist despite having adequate knowledge and awareness about it. Personal behaviour is a reflection of the individual's beliefs, experiences and teachings. Various studies have investigated the correlation between the attitudes of dental health care providers and improvement of their patient dental care.15,16,17 The aim of this cross sectional research study was to assess the oral hygiene practices and the self-reported dental status among the dental professionals in Riyadh, KSA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval

The cross sectional research design was used. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the College of Dentistry Research Centre, King Saud University, Riyadh (CDRC # IR 0226). The study was carried out between April 2017 and April 2018.

Data collection

The required information was collected through a self-administered questionnaire. Some questions of the questionnaire were adopted from previous studies1,11,12 and modified to suit the requirements of the present study.

The questionnaires along with a cover letter and consent form stating the instructions, rationale and purpose of the survey were distributed by hand to a conveniently selected sample of 400 male and female dental professionals studying and working in various private and governmental clinics and dental schools within Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

This method was adopted for convenience and to avoid the poor response rate by online distribution. The participants who were willing to participate in the study filled in the consent form and the questionnaire by hand and returned it immediately. There was no time limit for completion of the questionnaire. 275 participants completed the questionnaire with a response rate of 68.75%.

Questionnaire details

In addition to the demographic details the participants responded to questions related to their oral hygiene practices, past dental history, current dental status, dental appointments and dental condition of their families.

The questionnaire comprised of 25 questions and the participants were requested to select one answer and fill the numbers where required. In addition, they also graded their oral health condition on a 5 point Likert scale as: Excellent; Very good; Good; Fair and Poor.

The last question of the questionnaire was to get information about possible reason/reasons for negligence in oral health care of the participants, which comprised of 10 subsections.

The answers were based on Likert Scale as score of: 0 = Strongly disagree; 1=disagree; 2= Undecided; 3 = Agree and 4= Strongly Agree. The mean score of each question was calculated out of 4.0 with higher the number, indicating more negligence for that particular reason.

Statistical analysis

The data was analysed using IBM SPSS (Version 21) software. Descriptive statistics and Chi-square tests were used for statistical analysis of the responses considering a P-value of <0.05 as the cut-off level.

RESULTS

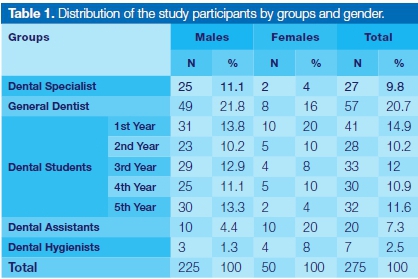

The response rate was 68.75%. Most respondents (81.8%) were males and (18.2%) were females. According to the distribution by groups: 27 (9.8%) were Dental Specialists; 57 (20.7%) were General Dentists; 164 (59.63%) were Dental Students; 20 (7.3%) were Dental Assistants and 7 (2.5%) were Dental hygienists (Table 1).

The questions used for assessment of the participants' self-reported oral hygiene practices and dental history are presented in Table 2. A significant difference between the responses of the male and female participants was observed for the questions related to the frequency of brushing (p = .001) and the history of dental visits (p = .013).

The frequency of tooth brushing as well as the time taken for brushing was more for the female participants compared to the males. History of the dental visits and past dental history were not significantly different between male and female participants.

The number and gender-wise percentage of participants' past dental complaints and social habits are presented in Table 3. Comparison using Chi-Square test only showed significant differences between males and females for extractions due to orthodontic treatment.

Differences between the responses related to coffee, tea, soft drink, cigarettes and water pipe (hookah) consumption or use were also insignificant.

The responses of the participants self-reported causes for their damaged dentition are presented in the Table 4. The majority of the participants (64% males and 68% females) agreed on poor oral hygiene to be the cause for their damaged dentition.

The percentage of bruxism causing damage to the dentition was higher in females (24%) than in males (10.7 %). Generally, the participants' overall experience with their dental treatment was very good to excellent.

Interestingly the percentage of participants with bad previous experiences of the dental treatment and dental anxiety was also very high (Figure 2). For the oral health of their family members, the participants reported a high percentage of fair oral health (49) (Figure 1).

The mean scores of the possible reasons for negligence in oral health by the participants are presented in Figure 2. The maximum score of 3.5 out of 4 was to avoid cross infection. This reveals that the dental professionals themselves are not confident about the cross infection control measures. The majority of the participants also believed that dental treatment is not very critical.

DISCUSSION

This study provides information about the oral hygiene practices and the oral health status of a group of dental professionals based on the information collected via a custom-designed self-administered questionnaire. The response rate of the questionnaire (55%) was found to be satisfactory.

Although some studies1,12-17 have been carried out about the oral hygiene practices and the oral health status of health care professionals, similar studies among the dental professionals are scarce in Saudi Arabia.

Some limitations were that respondents may not have been 100 percent truthful with their answers due to differences in understanding and interpretation of some questions and they may have been casual while completing the questionnaire as it was lengthy.

Another drawback of this present study was the lack of correlation of self-reported oral health with clinical or laboratory based evaluation. The authors were aware of limitations but still considered the method useful due to its practicability and speedy results. However, the interpretation of the results must be done with caution keeping in view the limitations mentioned above.

The evaluation of the results showed that there were differences in the oral hygiene practices, oral health status and oral health behaviour, between the male and female participants. However, the self-reported oral hygiene habits were excellent among the study participants, with most of the population reporting brushing twice daily. This was however anticipated as the subject population comprised of dental professionals.

Effective tooth brushing and flossing can significantly reduce oral malodour18,19 and the usage of dental aids such as the electric tooth brush, mouth wash, floss and a tongue cleaner were higher among females when compared to males. This could imply a more conscious attitude among females than among males and was evident from the results as the regular six monthly dental visit was two-fold higher among females (34%) as compared to males (15.5%).

In general, females engage in better oral hygiene behaviour measures, and studies have reported that females possess a greater interest in personal oral health than males.20 Studies conducted in Lebanon, Thailand, and Malaysia, have also found that female university students have better habits in term of tooth brushing than male students.21 However, in this study, no significant differences were noted among male and female students.

The results of this study showed the prevalence of dental caries among the male and female participants was the same. However, the percentage of males having gingival bleeding and gingivitis/periodontitis was higher in comparison to females. This finding could be related to the frequency of brushing, which was low among the males as compared to females; or related to the social habits such as smoking of cigarettes and water pipe (hookah) use.

Smoking has many confirmed adverse associations reported in a large quantity of literature ranging from negative impacts in gingival and oral health, to malignancies.22-25 The percentage of the male smokers (25.8%) was three to four folds higher compared to the females (4%) in this study.

Bivariate analysis of the self-perceived causes for damaged dentition of the participants showed no significant differences between the males and females, except for bruxism/clenching and congenital anomalies. The prevalence of bruxism is found to occur predominantly among females.26 This is also evident from the results of the study as the percentage of female participants having bruxism was three times higher than the male participants.

Generally, the majority of the participants reported to have had excellent and very good experiences with the dental treatment, oral health of the family and their own gum/teeth health for their self-evaluation of the oral health. This finding is line with the results reported by Al-Wahadni et al.12, in which the dental students were found to have more positive dental attitudes and behaviour, such as worrying more about visiting the dentist, having less gum bleeding when brushing their dentition. This might be explained by the fact that dental students receive more professional education in oral hygiene maintenance as compared to the general population and that the dentistry students are introduced to dental clinics very early and intensely during their dental education.

There are many reasons for possible negligence in oral health care that directly or indirectly affects the overall oral health status of the individuals.27 This study identified many reasons for negligence by the participants. Despite being involved in the cross infection control themselves the majority of the dental professionals were reluctant to seek dental treatment because of cross infection fear (Figure 2, Table 4).

Dental treatment which is not urgent, and a lack of trust in fellow dentists were also among the highlighted reasons for negligence in oral health by the participating dentists. Self-neglect was considered the least important reason for personal oral health negligence. These findings are similar to the previous studies conducted by Al Kawas et al.28, Al-Hussaini et al.29 and Halboub ES et al.30

Although the current study provides some information on the oral health behaviour among the dental professionals in this group, there is a need for further detailed studies among dental professionals to address this important subject. The factors affecting the oral health care such as fear of cross infection and the awareness of oral health care need to be evaluated and addressed further.

The authors believe that emphasis on dental health care should be developed and maintained during early education and training in order to improve the dental health behaviour of oral healthcare professionals later on. This is a key factor in developing their dental health attitudes and behaviours in order to allow them to have a positive impact on the dental health attitudes and behaviours of their patients.

CONCLUSION

The results show satisfactory oral hygiene practices and oral health status the participating dental professionals. Gender-based differences among the participants with regards to oral health attitude and behaviour revealed that females were more careful about their oral health. Gingival bleeding/gingivitis and bruxism were prevalent among the male and female participants respectively.

The majority of the participants' poor oral hygiene was the cause for their damaged dentition. Fear of cross infection from the dental treatment, dental treatment that was not critical, and a lack of trust in fellow dentists were the common reasons for negligence of oral health care among the participants.

References

1. Kumar H, Behura SS, Ramachandra S, Nishat R, Dash KC, Mohiddin G. Oral Health Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices Among Dental and Medical Students in Eastern India -A Comparative Study. J Int Soc Prev & Com Dent. 2017; 7: 58-63. [ Links ]

2. Skorupka W, Zurek K, Kokot T et al. Assessment of oral hygiene in adults. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2012; 20: 233-6. [ Links ]

3. Oberoi SS, Mohanty V, Mahajan A, Oberoi A. Evaluating awareness regarding oral hygiene practices and exploring gender differences among patients attending for oral prophylaxis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014; 18: 369-74. [ Links ]

4. Gomes APM, da Silva EG, Goncalves SHF, Huhtala MFRL, Martinho FC, Goncalves SEd. Relationship between patient's education level and knowledge on oral health preventive measures. IDMJAR 2015; 1: 1-7. [ Links ]

5. Thomas S, Tandon S, Nair S. Effect of dental health education on the oral health status of a rural child population by involving target groups. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2000; 18: 115-25. [ Links ]

6. Peter S. Essentials of Preventive and Community Dentistry. 2nd ed. New Delhi: Arya Publishing House; 2003. Health education; 534-58. [ Links ]

7. Nakre PD, Harikiran AG. Effectiveness of oral health education programs: A systematic review. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2013; 3: 103-15. [ Links ]

8. McGrath C, Zhang W, Lo EC. A review of the effectiveness of oral health promotion activities among elderly people. Gerodontology 2009; 26: 85-96. [ Links ]

9. Redmond CA, Blinkhorn FA, Kay EJ, Davies RM, Worthing-ton HV, Blinkhorn AS. A cluster randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of a school-based dental health education program for adolescents. J Public Health Dent. 1999; 59: 12-7. [ Links ]

10. Hazem Seirawan, MS, Sharon Faust, and Roseann Mulligan, DDS, MS. The Impact of Oral Health on the Academic Performance of Disadvantaged Children. Am J Public Health. 2012; 102: 1729-34. [ Links ]

11. Kirchhoff J, Filippi A. Comparison of oral health behavior among dental students, students of other disciplines, and fashion models in Switzerland. Swiss Dent J. 2015; 125: 1337-51. [ Links ]

12. Al-Wahadni AM, Al-Omiri MK, Kawamura M. Differences in self-reported oral health behavior between dental students and dental technology/dental hygiene students in Jordan. J Oral Sci. 2004; 46: 191-7. [ Links ]

13. Al-Omari QD, Hamasha AA. Gender-specific oral health attitudes and behavior among dental students in Jordan. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005; 6: 107-14. [ Links ]

14. Baseer MA, Alenazy MS, Al Asqah M, Al Gabbani M, Mehkari A. Oral health knowledge, attitude and practices among health professionals in King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh. Dent Res J. 2012; 9: 386-92. [ Links ]

15. Gopinath V. Oral hygiene practices and habits among dental professionals in Chennai. Indian J Dent Res. 2010; 21: 195-200. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.66636. [ Links ]

16. Zadik Y, Galor S, Lachmi R, Proter N. Oral self-care habits of dental and healthcare providers. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008; 6: 354-60. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00334.x. [ Links ]

17. Ghasemi H, Murtomaa H, Vehkalahti MM, Torabzadeh H. Determinants of oral health behaviour among Iranian dentists. Int Dent J. 2007; 57: 237-42. [ Links ]

18. Ashwath B, Vijayalakshmi R, Malini S. Self-perceived halitosis and oral hygiene habits among undergraduate dental students. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014; 18: 357- 60. [ Links ]

19. Morita M, Wang HL. Association between oral malodor and adult periodontitis: A Review. J Clin Periodontol 2001; 28: 813-9. [ Links ]

20. Mohammad AN. Gender-specific oral health attitude and behaviour among dental students. Malays Dent J. 2009; 6: 48-55. [ Links ]

21. Muthu J, Priyadarshini G, Muthanandam S, Ravichndran S, Balu P. Evaluation of oral health attitude and behavior among a group of dental students in Puducherry, India: A preliminary cross-sectional study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015; 19: 683-6. [ Links ]

22. Sreedevi M, Ramesh A, Dwarakanath C. Periodontal status in smokers and nonsmokers: a clinical, microbiological, and histopathological study. Int J Dent. 2012: 571590. [ Links ]

23. Tomar SL, Asma S. Smoking-atributable Periodontitis in the United States: findings from NHANES III. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Periodontol. 2000; 71: 743-51. [ Links ]

24. Rudziniski R. Effect of tobacco smoking on the course and degree of advancement inflammation in periodontal tissue. Ann Acad Med Stetin 2010; 56: 97-105. [ Links ]

25. Jalayer Naderi N, Semyari H, Elahinia Z. The Impact of Smoking on Gingiva: a Histopathological Study. Iran J Pathol. 2015; 10: 214-20. [ Links ]

26. Shetty S, Pitti V, Satish Babu CL, Surendra Kumar GP, Deepthi BC. Bruxism: a literature review. Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2010; 10: 141-8. [ Links ]

27. Randhawa RS, Chandan JS, Thomas T. Oral health: Dental neglect onwards. Br Dent J. 223, 238 (2017) doi:10.1038/ sj.bdj.2017.694. [ Links ]

28. Al Kawas S, Fakhruddin KS, Rehman BU. A comparative study of oral health attitudes and behavior between dental and medical students; the impact of dental education in United Arab Emirates. J Int Dent Med Res. 2010; 3(1): 6-10. [ Links ]

29. Al-Hussaini R, Al-Kandari M, Hamadi T, Al-Mutawa A, Honkala S, Memon A. Dental health knowledge, attitudes and behaviour among students at the Kuwait University Health Sciences Centre. Med Princ Pract. 2003; 12: 260-5. [ Links ]

30. Halboub E, Dhaifullah E, Yasin R. Determinants of dental health status and dental health behavior among Sana'a University students, Yemen. J Investig Clin Dent. 2013; 4: 257-64. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Asim K Alotaibi

King Abdulaziz Medical City, P. O. Box: 52104

Dubairah Street, Riyadh 12391, Saudi Arabia.

Email: asim.otb@gmail.com

Author contributions:

1 . Syed R Habib: Study Design, over all supervision, interpretation of data, write up and final review - 35%

2 . Asim K Alotaibi: Data collection, write up, review and submission - 20%

3 . Malek A Alabdulkader: Data collection, data entry - 15%

4 . Samer M Alanazi: Data collection, data entry - 15%

5 . Muhammad S Ahmedani: Statistical analysis, interpretation of data and results - 15%