Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.74 no.6 Johannesburg Jul. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2019/v74no6a3

RESEARCH

Prevalence of peri-implant mucositis at single tooth bone level dental implants in a South African population

S StanderI; PJ BothaII; CC PontesIII; H HolmesIV

IBChD (US/UWC), PDD Implantology (Cum Laude) (UWC), MChD Oral Medicine and Periodontology (UWC), Private Practice, Port Elisabeth and George. 240 Cape Road, Mill Park, Port Elizabeth, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0003-2792-6818

IIBChD, MChd (OMP), MSc Med Sci (Clin Epi), Specialist, Oral Medicine and Periodontology. Private Practice, 3 Zinnia Street, Bloemhof, Bellville, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0003-4510-181X

IIIPhD (Health Sciences), Research Consultant and Director of Smile@Research, 38C Higgo Crescent, Gardens, Cape Town, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0002-9337-3783

IVBChD, MSc Oral Medicine and Periodontology, MChD Oral Medicine and Periodontology (UWC), Senior Lecturer, University of the Western Cape Dental Faculty, Tygerberg Hospital Complex, Bellville, South Africa.ORCID Number: 0000-0001-8297-8536

SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION: Peri-implant mucositis (PIM) is characterized by inflammation of the soft tissues surrounding dental implants. It affects 43% of implant patients on average and despite its reversible nature, it can, if left untreated, progress to peri-implantitis and potentially implant failure. To date, there is a paucity of data on the prevalence of PIM in South Africa

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES: To determine the prevalence of peri-implant mucositis in patients from the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of the Western Cape, and to evaluate potential risk factors including systemic (smoking, diabetes), implant-related (implant position and diameter, connection and crown) and soft tissue-related (keratinized gingiva, oral hygiene) issues.

DESIGN: Cross-sectional cohort study

METHODS: A total of 74 partially edentulous patients with at least one implant that had been restored with a single crown for at least 12 months were clinically examined.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS: PIM was highly prevalent (70.3% of the sample), highlighting the need for maintenance programs for the long-term success of dental implants.

Anterior location of the implant, poor oral hygiene, pre-operative oral hygiene instructions and a wide band of KM were associated with PIM. However, due to the limited sample size, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

ACRONYMS

KM: Keratinized Mucosa

MDB: Peri-implant Mucositis

INTRODUCTION

Infection of the peri-implant soft tissues is a frequent cause of implant failure after healing.1 Peri-implant mucositis (PIM) is a condition characterized by inflammation of the soft tissues surrounding dental implants, affecting on average 43% of implant patients.2,3 Despite the fact that PIM is a reversible condition, it has the potential to progress to peri-implantitis if left untreated, a condition in which the inflammatory response results in bone destruction and potentially implant failure.4,5 Currently, there is no consensus on the best approach to treat peri-implantitis, making prevention the most important strategy.3

It has been suggested that the anatomical characteristics of the peri-implant mucosa make it more prone to inflammatory changes when compared with gingival tissues around teeth, mainly due to poorer connective tissue attachment and reduced vascular supply.6,7 The primary etiological factors for developing PIM are the presence of biofilm and the elicited host response. A variety of other factors can contribute to the development and progression of the disease, including patient-related, implant-related and prosthetic-related factors. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that appropriate maintenance therapy, customized according to the patient's risk, is important to limit the development of biological complications such as PIM.8

To date, there is a paucity of data on the prevalence of PIM in South Africa. The aim of the present cross-sectional study was to determine the prevalence of peri-implant mucositis in a sample of patients from the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of the Western Cape, South Africa, and to evaluate potential risk factors, whether systemic (smoking, diabetes), implant-related (implant position in the arch, type of connection, implant diameter, type of crown,) or soft tissue-related (width of keratinized gingiva, oral hygiene) issues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study protocol was approved by the Research Committee from the University of the Western Cape (registration number 12/1/19).

Sample size calculation

The population from which the sample was generated consisted of patients from the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of Western Cape, who had had a single implant-supported crown placed during the period 2005 to 2011.

Partially edentulous patients with at least one implant that had been restored with a single crown for at least 12 months were included. Only bone level implants placed and restored according to the delayed protocol were included. Excluded were those cases having had bone or soft tissue grafting during implant placement, immediate implants, tissue level implants, bridge restorations and splinted crowns.

The literature reports the prevalence of peri-implanti-tis among various populations to be 43% on average.3 This figure was used to calculate the recommended sample size of 97 for this cross-sectional study in order that precise data could be generated, with a 95% confidence interval to fall within 10% of the estimate. The University records offered 120 eligible patients, of whom 100 were randomly selected to receive a free recall and oral hygienist visit. Of the 100 patients contacted, 74 agreed to participate in the study.

Data collection

A standardized form was use to collect patient information, including follow-up time after implant placement, gender, smoking status (current smoker or non-smoker), diabetes (self-reported, yes or no). Data on the implant included position in the dental arch (anterior from incisors to canines or posterior at pre-molar and molar sites), implant diameter ("standard" if between 3.7mm and 4.2 mm or "wide" if greater than 4.2 mm), type of restoration (screw or cement-retained crown).

Peri-implant mucositis was diagnosed according to the 7th European Workshop of Periodontology consensus, as the presence of bleeding in at least one site after gentle probing (<0.25N).9 The clinical parameters were measured by a calibrated examiner at the implant site using a pressure constant probe (Vivacare TPS Probe, Schaan, Liechtenstein) at a probing pressure of 20g.

The oral examination included measurement of the width of keratinized gingiva (<1mm; >1-2mm; >2mm) and recording of bleeding on probing at six sites per implant (mesio-buccal, buccal, disto-buccal, mesiolingual, lingual, and distolingual).

Oral hygiene was evaluated according to the modified plaque index from Silness & Loe.10 Toothbrushing frequency, flossing frequency and use of mouthwash was categorized into twice daily, every second day and never. Patients were asked whether oral hygiene instructions had been given prior to implant or crown placement.

Statistical analysis

A chi-square test was used to evaluate the relationship between PIM and the local and general risk factors in the studied population through a statistical software program. A 95% confidence interval was used and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 74 patients with at least a single implant each were evaluated, of whom 72% were females (n=53) and 28% males (n=21). The age range varied between 20-84 years, with the majority (63.5%, n=47) being 50 years and older (Table 1). Peri-implant muco-sitis was detected in 70.3% of the sample (n=52,) with no statistically significant differences between affected males (71.4%) and females (69.8%). Average follow-up time was 3 years and four months.

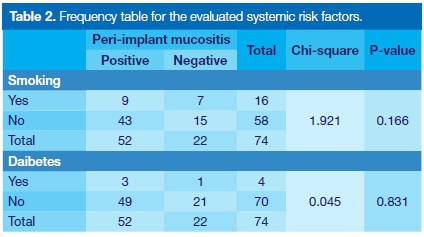

Systemic risk factors

Diabetes was present in 5% (n=4) of the sample. A total of 22% (n=16) of the patients were smokers. Prevalence of PIM was not statistically associated with smoking or diabetes (Table 2).

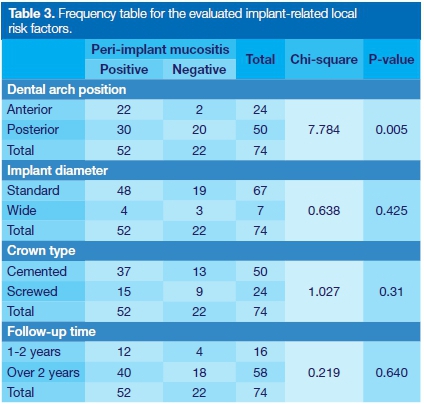

Local risk factors

For the implant-related variables, 68% of the implants had been placed in posterior areas. The anterior implants (32 %) were associated with an increased prevalence of PIM (p=0.005). Regarding implant diameter, the majority of the implants (91%, n = 67) had standard diameters, while 9% were wide. This variable was not statistically associated with prevalence of PIM (Table 3).

A total of 68% (n=50) of the crowns were cement-retained, while 32% were screw-retained ( n=24); there were no significant differences between the groups in relation to the prevalence of PIM. Follow-up time after implant placement was categorized into 1-2 years (22%, n=16) and above 2 years (78%, n=58), with no statistical differences observed between groups for PIM prevalence (Table 3).

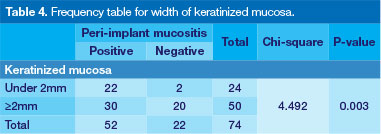

The data recording the width of keratinized mucosa (KM) were divided into two categories, less than 2 mm (n=21, 28%) and 2mm and above (n = 53, 72%). Prevalence of PIM differed between these groups, 22 patients presenting with PIM in areas with 2mm or less, compared with 30 patients in the group with at least 2mm of keratinized gingiva (p = 0.03, Table 4).

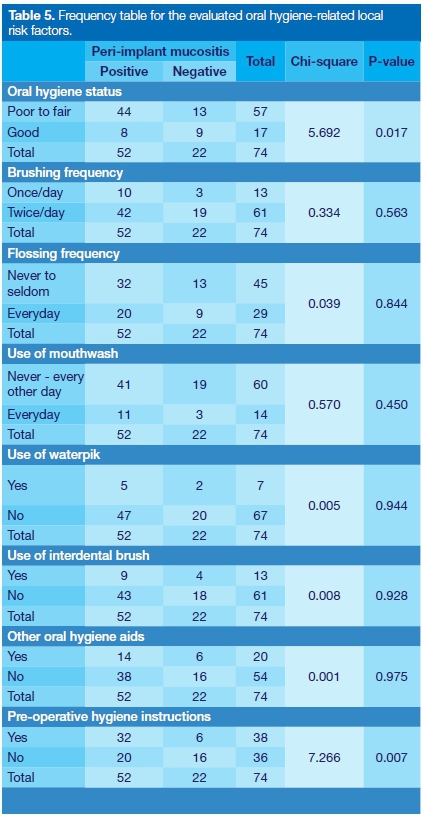

A total of 57 patients (77%) had poor to fair oral hygiene, while 17 (23%) presented good oral hygiene. The two groups differed, with 44 patients presenting PIM in the poor to fair oral hygiene group and 8 in the good oral hygiene group (p = 0.02). Brushing once (n=13, 18%) or twice a day (n = 61, 82%) had no association with the incidence of PIM. Frequency of flossing, described as never to seldom (n=45) or daily (n = 29) was not associated with prevalence of PIM, neither was use of mouth rinse, categorized into never or every other day (n=60) or daily (n=14). Use of other oral hygiene aids, waterpik and interdental brush were not associated with prevalence of PIM (Table 5).

A total of 38 (51%) patients received oral hygiene instructions prior to implant placement, while 36 (49%) patients received no pre-surgery instructions. A higher prevalence of PIM was present for the group that had pre-treatment instructions (n=32), as compared with the group who had received no instructions (n=20, p = 0.007).

Among the evaluated factors, anterior location (odds ratio [OR]=7.3), having received pre-operative oral hygiene instructions (OR=4.2), having poor to fair oral hygiene habits (OR=3.8) and having a band of keratinized gingiva of at least 2mm (OR=0.3) were associated with PIM (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

Understanding the epidemiology of peri-implant diseases is the first step for the development of preventive strategies.3 The primary aim of this cross-sectional study was to determine the prevalence of PIM in a South African sample of patients who had a single bone level implant placed at the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of Western Cape.

The secondary objective was to assess possible associated risk factors. However, the sample size was calculated based on the primary objective, and hence was too small to draw definitive conclusions about the role played by the systemic and local factors that were measured. Our findings revealed a diagnosis of PIM in 70.3% of all evaluated single crown implant supported crowns. This surpasses prevalence rates of PIM that have been reported in the literature.3,9

A systematic review on the epidemiology of peri-implant mucositis worldwide reported prevalence rates ranging from 19 to 65%, with average of 43%.3 Few studies have presented PIM prevalence rates over 70%. Henriques et al. (2016) reported that 81% of implants placed at a Brazilian University were diagnosed with PIM. The average follow-up time in that study was 2.6 years.11

Two cross-sectional studies evaluated implants that had been in function for more than Ave years and reported PIM in 79% of the subjects12 and in over 90% of the implants.13 A study from Rinke and coworkers (2011) showed that in patients with a history of periodontitis who smoked, prevalence of PIM was 80%; mean follow-up time was 5.6 years.14 Differences in prevalence rates can be attributed to variations in case-definition, level of analysis (subject or implant), follow-up time, population type and type of implant-supported restoration.5,15

Certain population groups can present higher risk for peri-implant diseases.15 The current study included patients who had their implants placed at a University Clinic; none of them had been enrolled in maintenance programs after implant placement, which could be one of the reasons for the high prevalence of PIM. Since patients who received oral hygiene instructions prior to implant surgery had higher prevalence of PIM, our results indicate that pre-operative instructions are not of themselves sufficient to maintain peri-implant health, highlighting the need for consistent follow-up to control plaque and potentially to prevent peri-implant diseases.8

From the evaluated risk factors, none of the self-reported systemic factors were associated with PIM, which contradicts previous studies suggesting a role for smoking and diabetes.1,12,14,16 Reliability of self-reported data can be considered as a potential limitation, as indicated in an epidemiological study by Ning et al. (2016), where prevalence of self-reported diabetes was underestimated when the same patients were subjected to glucose tests.17

In our study, implants located in the anterior area had 7.3 higher odds of having PIM. The majority of the implants (75%) in the anterior area had cemented crowns. Although no statistically significant association was found between location of the implant, type of crown and PIM, the detrimental effect of residual cement cannot be underestimated and the lack of significance can be related to the small sample size.18

The role of plaque has been well established in the development of PIM, hence oral hygiene is essential for the long-term success of dental implants.19-22 According to our results, poor oral hygiene increased the odds of having PIM 3.8 times, highlighting the importance of plaque control and follow-up.

The presence of a band of KM of 2 mm and above had a weak association with PIM (OR=0.3) in our study. In the literature, there is evidence of a protective effect of a wide band of KM23, evidence of the opposite, with KM being a risk factor for PIM12 and other studies suggesting that KM is not as important as maintenance and plaque control for the development of PIM.22,24 Thus, our findings are difficult to interpret; further studies are required to explore the role of KM for peri-implant diseases.

The main limitation of the study is the lack of data on periodontitis, since several studies have suggested previous periodontitis as a predisposing factor to PIM.19,25,26 Another limitation is the lack of radiographs, which could have resulted in the identification of peri-implantitis cases. In future studies, it will be interesting to evaluate other potential risk factors, such as titanium corrosion, which has been recently linked to irritation of peri-implant tissues.27

CONCLUSIONS

This first study on PIM in South Africa revealed high prevalence rates in the studied sample, highlighting the need for supportive maintenance care programs for the long term success of dental implants. In this study, anterior location of the implant, poor oral hygiene, pre-operative oral hygiene instructions and a wide band of KM were associated with the prevalence of PIM. However, due to the limited sample size, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Further studies are necessary in order to provide a better understanding of the risk factors associated with PIM.

the long term success of dental implants. In this study, anterior location of the implant, poor oral hygiene, pre-operative oral hygiene instructions and a wide band of KM were associated with the prevalence of PIM. However, due to the limited sample size, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Further studies are necessary in order to provide a better understanding of the risk factors associated with PIM.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Karbach J, Callaway A, Kwon Y-D, d'Hoedt B, Al-Nawas B. Comparison of five parameters as risk factors for peri-mu-cositis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2018; 24: 491-6. [ Links ]

2. Jepsen S, Berglundh T, Genco R, et al. Primary prevention of peri-implantitis: Managing peri-implant mucositis. J Clin Periodontol. 2015; 42: S152-S157. [ Links ]

3. Derks J, Tomasi C. Peri-implant health and disease. A systematic review of current epidemiology. J Clin Periodontol. 2015; 42: S158-S171. [ Links ]

4. Salvi GE, Aglietta M, Eick S, Sculean A, Lang NP, Ramseier CA. Reversibility of experimental peri-implant mucositis compared with experimental gingivitis in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012; 23: 182-90. [ Links ]

5. Zitzmann NU, Berglundh T. Definition and prevalence of peri-implant diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2008; 35: 286-91. [ Links ]

6. Degidi M, Piattelli A, Carinci F. Clinical outcome of narrow diameter implants: a retrospective study of 510 implants. J Periodontol. 2008; 79: 49-54. [ Links ]

7. Wang Y, Zhang Y, Miron RJ. Health, maintenance, and recovery of soft tissues around implants. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2016; 18: 618-34. [ Links ]

8. Monje A, Aranda L, Diaz KT, et al. Impact of maintenance therapy for the prevention of peri-implant diseases. J Dent Res. 2016; 95: 372-9. [ Links ]

9. Lang NP, Berglundh T. Peri-implant diseases: where are we now? Consensus of the Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2011; 38: 178-81. [ Links ]

10. Löe H. The Gingival Index, the Plaque Index and the Retention Index Systems. J Periodontol. 1967; 38: 610-6. [ Links ]

11. Henriques PSG, Rodrigues AEA, Peruzzo DC, et al. Prevalence of peri-implant mucositis. Revista Gaúcha de Odontologia. 2016; 64: 307-11. [ Links ]

12. Roos-Jansâker A-M, Lindahl C, Renvert H, Renvert S. Nine- to fourteen-year follow-up of implant treatment. Part II: presence of peri-implant lesions. J Clin Periodontol. 2006; 33: 290-5. [ Links ]

13. Fransson C, Wennström J, Berglundh T. Clinical characteristics at implants with a history of progressive bone loss. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008; 19: 142-7. [ Links ]

14. Rinke S, Ohl S, Ziebolz D, Lange K, Eickholz P. Prevalence of peri-implant disease in partially edentulous patients: a practice-based cross-sectional study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2011; 22: 826-33. [ Links ]

15. Charalampakis G, Jansåker E, Roos-Jansåker A-M. Definition and prevalence of peri-implantitis. Curr Oral Heal Reports. 2014; 1: 239-50. [ Links ]

16. Ferreira SD, Silva GLM, Cortelli JR, Costa JE, Costa FO. Prevalence and risk variables for peri-implant disease in Brazilian subjects. J Clin Periodontol. 2006; 33: 929-35. [ Links ]

17. Ning M, Zhang Q, Yang M. Comparison of self-reported and biomedical data on hypertension and diabetes: findings from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). BMJ Open. 2016; 6: e009836. [ Links ]

18. Linkevicius T, Puisys A, Vindasiute E, Linkeviciene L, Apse P. Does residual cement around implant-supported restorations cause peri-implant disease? A retrospective case analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012; 24: 1179-84. [ Links ]

19. Roccuzzo M, Bonino L, Dalmasso P, Aglietta M. Long-term results of a three arms prospective cohort study on implants in periodontally compromised patients: 10-year data around sandblasted and acid-etched (SLA) surface. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2014; 25: 1105-12. [ Links ]

20. Serino G, Strom C. Peri-implantitis in partially edentulous patients: association with inadequate plaque control. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009; 20: 169-74. [ Links ]

21. Pjetursson BE, Helbling C, Weber H-P, et al. Peri-implantitis susceptibility as it relates to periodontal therapy and supportive care. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012; 23: 888-94. [ Links ]

22. Renvert S, Polyzois I. Risk indicators for peri-implant mucositis: a systematic literature review. J Clin Periodontol. 2015; 42: S172-S186. [ Links ]

23. Zigdon H, Machtei EE. The dimensions of keratinized mucosa around implants affect clinical and immunological parameters. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008; 19: 387-92. [ Links ]

24. Frisch E, Ziebolz D, Vach K, Ratka-Krüger P. The effect of keratinized mucosa width on peri-implant outcome under supportive post-implant therapy. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2015; 17: e236-e244. [ Links ]

25. Karoussis IK, Salvi GE, Heitz-Mayfield LJA, Brágger U, Hámmerle CHF, Lang NP. Long-term implant prognosis in patients with and without a history of chronic periodontitis: a 10-year prospective cohort study of the ITI Dental Implant System. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003; 14: 329-39. [ Links ]

26. Sgolastra F, Petrucci A, Severino M, Gatto R, Monaco A. Periodontitis, implant loss and peri-implantitis. A meta-analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2015; 26: e8-e16. [ Links ]

27. Penmetsa SD, Shah R, Thomas R, Kumar AT, Gayatri PD, Mehta D. Titanium particles in tissues from peri-implant mucositis: An exfoliative cytology-based pilot study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2017; 21: 192. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Paul J Botha

Specialist Oral Medicine and Periodontology

Private Practice, 3 Zinnia Street

Bloemhof, Bellville, South Africa

Tel: +27 (0)21 910 3330

Email: p.mbotha@mweb.co.za

1 . Suzette Stander: Principal researcher - 45%

2 . Paul J Botha: Supervisor - 20%

3 . Carla C Pontes: Scientific writing - 20%

4 . Haly Holmes: Research - 15%