Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562

Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.74 n.4 Johannesburg May. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2019/v74no4a2

RESEARCH

Dental status of children receiving school oral health services in Tshwane

MM MoleteI; J IgumborII; A StewartIII; V YengopalIV

IBDS (Wits), MSc Dental Public Health (Kings College, MDent (Wits), Community Dentistry, School of Oral Health Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Yale Road, Parktown, 2193, South Africa. ORCID Number: 0000-0001-9227-3927

IIPhD, School of Public Health , Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Yale Road, Parktown, 2193, South Africa

IIIPhD, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Yale Road, Parktown, 2193, South Africa

IVPhD, School of Oral Health Sciences *Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Yale Road, Parktown, 2193, South Africa

SUMMARY

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: School health services and baseline oral health information are central to monitoring the progress of ongoing reforms, addressing areas requiring improvement and revitalization of South African primary health care.

The study described the dental status of learners receiving oral health services in Tshwane, and assessed the influence of factors such as age, gender, location, and services received.

METHODS: A cross-sectional analytical study design with a multistage sampling technique was employed to randomly select ten schools. Oral health examinations were conducted on all learners in two selected grades in each school

RESULTS: There were 736 participants, ages 6 to 16 years, 50.9% were girls. Dental caries prevalence in the permanent dentition was 25.9% and in the primary dentition, 30.2%. Mean DMFT/dmft scores were [(0.90; SD:1.7; SiC :2.7); (1.2;SD:2.3; SiC:3.7)] respectively

PUFA/pufa prevalence mostly affected the primary dentition (pufa 5,2% vs PUFA 2.2%). The unmet treatment need (UTN) was 89.6% and associated factors included gender, location and type of services received.

CONCLUSION: The prevalence of dental caries was relatively low in comparison with similar South African studies, but untreated disease levels were high. Most affected were females, primary school learners, urban learners and those not participating in a supervised tooth brushing programme

Keywords: Dental epidemiology, school oral health, health programmes, oral health services.

INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND

Dental caries is a neglected public health problem globally and the incidence in developing countries is increasing at an alarming rate.1-3 In South Africa, the high curative need of the condition is of concern, as over 90% of children in the country go untreated for dental caries.4,5

Though the disease is amenable to prevention and existing mechanisms of prevention are available, the multifac-torial aetiology is affected by the type of diet intake, socio-economic standing, environmental factors such as water fluoridation, availability of dental services and utilisation of care.6-8

These factors influence the pattern of the disease and experiences across and within populations as a result of the varying risk profiles,9 hence planning for oral health preventative programmes becomes a complex task.

School based settings around the world have been identified as platforms ideal for delivering oral health promotion and care to children as they are more likely to adopt healthy habits earlier and it is easier at these stages to equip them with personal skills such as maintaining personal hygiene, brushing teeth and adopting a healthy diet.10,11 These foundatio-nal skills when re-enforced over years subsequently contribute to better oral health experiences over the growing years.12 The success of such programmes in reducing the incidence of caries has been reported in some studies.13,14 However, implementation of the programmes has been shown to come with a variety of contextual challenges.15-17

South Africa is embarking on health reforms by introducing a National Health Insurance financing policy aimed at redressing health inequities and ensuring universal health coverage for all citizens.18

Primary health care revitalization will be key to the transformation process as it will be central to service delivery, facilitating health promotion, prevention of illness and a first point of entry into the healthcare sector.19

One of the revitalization streams include school health services which are currently being piloted across 11 provincial sites in the country.19,20 Oral health is included in the school health services and this provides a valuable platform for introducing early oral health care interventions in order to delay the onset and control the severity of dental caries.21

The City of Tshwane health district has been piloting the School Health Service Programme since 2011 and Oral Health has been incorporated since 2013. Tracking the success of these new reforms needs periodic data at baseline,22 however, such information is lacking from school health programmes where health reforms are being tested. The dearth of baseline data makes it imperative to conduct a survey against which progress of the programmes can be measured in the future.

This study is part of a larger study that is assessing the scope, implementation and outcomes of school oral health programmes in Tshwane. The aim of this paper is to describe the dental status of school learners and to assesses the influence of contextual factors on the dental status of the learners at schools in Tshwane. Subsequent papers will focus on implementation processes and how these processes influence different outcomes.

METHODS

This cross-sectional analytical study was undertaken in the Tshwane Health District of Gauteng. Tshwane is a large metropolitan municipality situated in the northern part of the Gauteng Province in South Africa. It has a population of 2,9 million with an unemployment rate of 24.2%.23 It is demarcated by seven regions with a mix of urban and peri-urban components and the economic situation of residents is mostly dependent on the area in which they are located.24 There are therefore socio-economic differences between the urban and peri-urban schools as more working parents are located in urban settings.23,24

The oral health services in the area have ten oral hy-gienists who manage school oral health programmes at various locations in the District and each oral hygienist is responsible for a number of the programmes in a specific locality. The activities at the school are planned to include oral health education, supervised tooth brushing and Assure sealant programmes. All the schools received some oral health education but due to a variety of factors, not all received a combination of a supervised toothbrush programme and Assure sealants.

All ten oral hygienists were recruited to participate in this study. Schools included had to have been receiving the services for more than a year. A multistage sampling technique was employed. In the first stage one school that met the inclusion requirements was randomly selected from the portfolio of each oral hygienist. The second stage included a random selection of one class of grade 1 and one class of grade 7 learners at each participating school. Grades 1 & 7 learners were selected as they generally had ages ranging between 6/7 and 12/13 years, which are the ages recommended for dental surveys.25 A sample of approximately 700 learners was required to enable the estimation of the mean DMFT with a precision of ±0.3,26 assuming the standard deviation was 2.0 with a design effect of 2, which took into account the clustering effect of pupils within schools (Statcalc, version 14).

The oral health examinations were undertaken using the Decayed Missing Filled Teeth Index (DMFT/ dmft) and the Pulpal Ulceration Fistula Abscess Index (PUFA/pufa).27 All procedures in the survey were followed according to the WHO guidelines.25 Two examiners conducted the examinations, having been trained and calibrated. Inter-rater reliability was established by conducting repeat examinations of images until Cohen's Kappa score was greater than 0.80.

During the study, the participants were seated and the oral cavity was examined in a well-lit room using a light, mouth mirror and a community periodontal index probe.25 Information on the programme activities was derived from the Oral Hygienists.

Descriptive summary statistics were used to calculate the dental health status and the results were initially categorised into four age groups (6-7); (8-10); (11-12); (13-16) in order to provide a broad overview of the dental scores across the ages. As the numbers were not well distributed across the four groups, the age groups had to be stratified into two groups (6-7) and (8-16) in order to obtain sufficient numbers and power for further analyses assessing dental status according to gender, setting & services received.

A multiple linear regression was then undertaken to determine the size of effect of the dependent variables (gender, location, services) on the independent variables (DMFT, dmft, PUFA, pufa). For the 8-16 age stratum, analysis of the dmft and pufa were excluded from the regression models, as the scores were shown to be decreasing with age - as was expected because exfoliation was still occurring during those age ranges. All the data were analysed using STATA software version 14.

The proportion of unmet treatment need index (UTN) was calculated by dividing the percentage of untreated caries over the caries prevalence (% UTN = % untreated caries/caries prevalence).28 The significant caries index (SiC) was also calculated in order to determine the one third of the population carrying the highest caries score. Individual DMFT/dmft scores were sorted in a descending order, one third of the population with the highest scores was then selected and the mean DMFT/dmft for the subgroup was calculated in order to determine the SiC, The calculations were performed on Excel software.29

The study obtained ethical clearance from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (M170115), and written approval was obtained from the Gauteng Department of Education. All learners participating had written consent from their parents and they assented to participation.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

Of the 736 learners who participated in the study, 49.7% (n=366) were grade 1 primary school learners; with ages ranging between 6-12 years. The secondary school learners (50.1%; n = 370) had ages ranging between 11-16 in grade 7. The participants consisted of 50.9% girls and 49.0% boys. Seven of the schools were located in an urban setting and three were located in a peri-urban setting.

Dental status

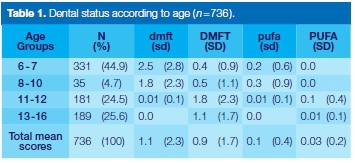

The prevalence of dental caries in the permanent dentition was 25.9% and in the primary dentition, 30.2%. Table 1 demonstrates that the largest age group (n=331) among the participants was that of 6-7 year learners and the least (n=35) were the 8-10 year olds. The mean dmft was highest 2.5 [2.8] among the 6-7 year olds and mean DMFT was highest 1.8 [2.3] among the 11-12 year olds. Similarly pufa most affected the 6-7 and 8-10 year groups, while the PUFA was high among the 11-12 year old learners.

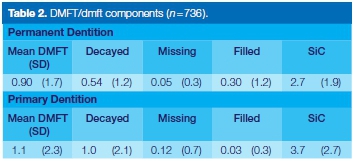

The DMFT/dmft results indicated that the "decayed" component was the major contributor to the DMFT/dmft scores, as displayed in Table 2. The SiC index was significantly higher (p<0.001) than the mean DMFT/dmft in both the primary (3.7) and secondary dentitions (2.7).

The PUFA/pufa components

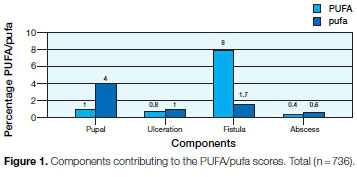

The prevalence of PUFA/pufa mostly affected the primary dentition (pufa 5,2% vs PUFA 2.2%). Figure 1 shows that fistula lesions (8%) contributed more in the permanent dentition and the pulpal lesions (4%) contributed more in the primary dentition.

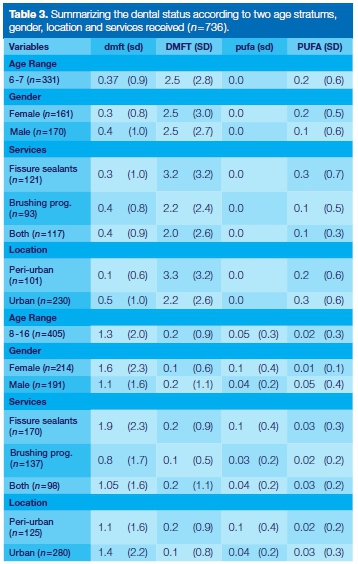

Table 3 describes the dental status according to age, gender, services received and setting. There were no PUFA scores among the 6-7 year old age stratum. In this group most of the learners were exposed to the Assure sealant services (n=121), and the majority were from urban areas (n=230).

Among the 8-16 year old age stratum, the dmft and pufa scores with regards to age, gender, services and setting were less than the mean of 1. More of these learners were females, furthermore the majority received Assure sealants (n=170) and were from urban areas (n=280).

Factors influencing the dental status

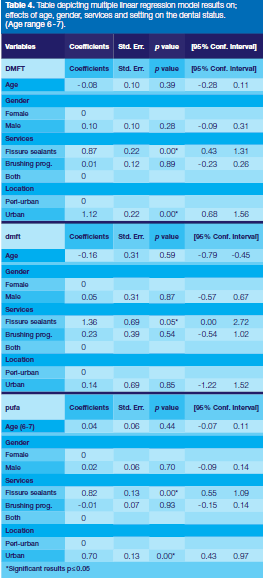

All the key exposure variables were inserted into the multiple linear regression model in order to determine the size of the effect of the variables on the dental status. The DMFT of the 6-7 year old learners from urban areas increased (by a Coef: 1.12; p=0.00) in comparison with learners from peri-urban areas (Table 4).

Furthermore, learners who received only fissure sealants instead of both programmes had increased levels of DMFT (Coef: 0.87; p=0.00). A similar increasing effect (Coef: 1.36; p=0.05) was seen on the dmft scores of children that just received fissure sealants. The pufa scores were influenced by location and services. Children who were located in urban areas and received Assure sealants only had increased pufa scores respectively (Coef: 0.70; p =0.00); (Coef: 0.82; p=0.00).

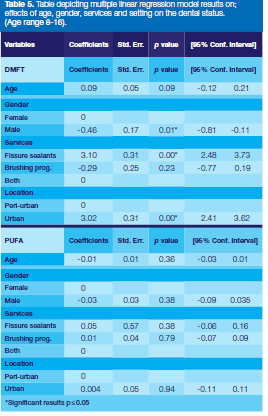

Table 5 outlines the regression results of the 8-16 age stratum and indicates that the DMFT of the male learners decreased (Coef: -0.46; p = 0.01) in comparison with the female learners. In addition, learners located in urban areas (Coef: 3.02; p = 0.00) and those who received Assure sealants only (Coef: 3.10; p=0.00) had increased levels of DMFT over those from peri-urban areas and those exposed to both fissure sealants and brushing programmes. There were no significant influencing factors on PUFA.

The Unmet Treatment Need (UTN) for the permanent dentition (DMFT) was 55,5% and for the primary dentition (dmft) 89.6%. This implied that close to 90% of the affected learners required treatment for dental caries. The SiC Index was statistically significant for both the primary teeth (dmft) and permanent teeth (DMFT) indicating that the concentration of the disease was narrowly distributed among one third of the population in this cohort (p <0.001).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that the prevalence of dental caries in this population was relatively low in comparison with results from similar studies in South African schools.3-5 Reasons could be attributed either to exposure to fluoridated water by children accessing borehole water in the Tshwane rural locations, or that learners were recipients of oral health programmes and were able to access preventative care.30

Gender, location and services received emerged as key associated factors influencing the status and severity of dental caries in this population. The female learners, learners in urban schools and those with no exposure to a brushing programme had higher levels of dental caries. The severity of dental caries affected the 6-7 year old group the most and learners located in urban areas across the ages were the worst affected.

The 8-16 year old males had lower DMFT than females. The cause of the gender bias is uncertain, however, studies suggest that it may be due to gene-by sex interactions involved in the dental experience.31,32 Others report that it could be due to females experiencing early eruption times of teeth, thereby having longer exposure to cariogenic foods. In addition it has been observed that the fluctuating levels of estrogen in females during puberty and menstruation suppress the salivary flow rate, affect its composition and subsequently result in caries susceptibility.32

The prevalence of dental caries on the permanent teeth of the urban learners was higher than those in rural areas and the primary teeth were similarly affected by the location. The change in nutrition as most families migrate from a peri-urban to urban settings for employment is contributory.30,33 In addition, as the majority of children in urban schools have working parents, the children often had access to school snack money in addition to healthy government school lunches.

In peri-urban schools learners were more reliant on the government school meals and had less exposure to snacks. Other South African studies have demonstrated a similar phenomenon on oral health trends between urban and non-urban localities.5,30,33 This has largely been attributed to the higher urban sugar expenditure [mean urban 8.06 (2.78) vs non-urban 7.35 (1.94)] and reduced access to borehole water which is higher in natural fluoride than the reticulated public water supply in cities.5,33

Learners who were exposed to only a Assure sealant programme versus both the supervised brushing and Assure sealants, had higher levels of caries across the age groups and higher severity of the condition among the 6-7 year olds. This implies that a more comprehensive programme may be favourable in terms of controlling the condition at schools.11

Studies have also demonstrated that fissure sealant retention tends to be a challenge particularly when not placed in ideal clinical conditions.34 It must also be noted that fissure sealants are targeted to protect permanent molars and not primary teeth or the rest of the oral cavity, hence the negative result.11 The results are also dependent on the type of fissure sealants used. Moisture tolerant glass ionomer fissure sealant materials may have resulted in better outcomes in field conditions as some studies have demonstrated.35

The severe consequences of dental caries mostly affected the primary dentition as the pufa was high amongst the 6-7 & 8-10 year groups. This indicated that some form of dental neglect or poor access to treatment had been experienced, hence disease consequences such as pulpitis and fistulas resulted.27 A review of parental influence on the development of caries reported that high levels of untreated caries often resulted from a combination of factors.

These could include geographic isolation leading to difficulty in travelling to services; parental attitudes, knowledge and beliefs. Attitude, knowledge and beliefs are implicated as this often determine the choices parents make for their children in terms of taste preferences in diet and dental hygiene and care.36,37 Furthermore there is poor perception of the importance of primary teeth and a lack of knowledge and awareness on the significance of oral health, particularly among parents with poor education.36,37

Although the prevalence of caries was low in comparison with similar studies in South Africa and the WHO goal of mean DMFT of 3 among 12 year olds. The SiC index was high in both the primary and permanent teeth implying that the disease was unevenly distributed in this cohort and it was a few children who were carrying the major burden of the disease. This means that consideration may need to be given to the implementation of a high risk prevention approach on some services in order to address the needs of those highly affected. However this has to be carefully executed in order to avoid neglecting the rest of the learners.38

A high unmet need of over 89% was found. This is surprising given that the learners were recipients of oral health services. The parents may possibly not be following up on the referrals generated from the oral health screening processes39 or the healthcare professionals at the facilities may have been experiencing difficulties in attending to the restorative needs of the children for various reasons. Young children often exhibit anxiety and fear towards dental treatment, this then is expressed in disruptive behaviour while in the chair.40 Dental treatment is then hindered, particularly in public health facilities that are characterised by high patient loads and time limitations.41

Limitations

The main purpose of the study was to highlight the oral health status of the learners receiving ongoing oral health services and to ascertain the factors influencing the oral disease experience at the school settings.

The study was observing existing participating schools in uncontrolled conditions, therefore settings and services received could not be controlled for equal distribution.

Future studies will expand more on processes of programme implementation and how this influences the oral health status of learners. In addition, as this was a cross sectional analytical study no causal inferences could be made.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence and severity of dental caries was relatively low in this population, however the unmet treatment need and the SiC index were high. The consequences of the disease affected the primary teeth of the learners most and the factors associated with the disease were influenced by gender, location and the type of services offered by the programmes. Female learners had higher levels of dental caries on the permanent teeth of 8-16 year olds, and across the ages learners from urban locations and those who only had access to a Assure sealant programme and not a combination of services were worst affected.

Funding

This research was supported by the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA). CARTA is jointly led by the African Population and Health Research Centre and the University of the Witwatersrand and is funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York (Grant No-B 8606.R02), Sida (Grant No: 54100113), the DELTAS Africa Initiative (Grant No: 107768/Z/15/Z) and Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD).

The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)'s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and is supported by the New Partnership for Africa's Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust (UK) and the UK Government. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the CARTA Fellow (Dr MM Molete).

ACRONYMS

DMFT/dmft: Decayed Missing Filled Teeth Index

PUFA/pufa: Pulpal Ulceration Fistula Abscess Index

SiC: Significant Caries Index

UTN: Unmet Treatment Need Index

References

1. Bagramian, RA, Garcia-Godoy, F, Volpe, AR. The global increase in dental caries. A pending public health crisis. American Journal of Dentistry, 2009; 22(1):3-8. [ Links ]

2. Marcenes, W, Kassebaum, NJ, Bernabé, E, Flaxman, A, Naghavi, M, Lopez, A, Murray, CJ. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: A systematic analysis. Journal of Dental Research, 2013; 0022034513490168. [ Links ]

3. Reddy, M, & Singh, S. Dental Caries status in six-year-old children at Health Promoting Schools in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. South African Dental Journal, 2015a; 70(9):396-401. [ Links ]

4. Thekiso M, Yengopal V, Rudolph MJ, Bhayat A. Caries status among children in the west Rand District of Gauteng Province, South Africa. South African Dental Journal 2012; 67(7):318-20. [ Links ]

5. Wyk, PJ, Wyk, C. Oral health in South Africa. International Dental Journal 2004; 54(S6):373-7. [ Links ]

6. Casamassimo, PS, Thikkurissy, S, Edelstein, BL, Maiorini, E. Beyond the dmft: the human and economic cost of early childhood caries. The Journal of the American Dental Association 2009; 140(6):650-7. [ Links ]

7. Fisher-Owens SA, Gansky SA, Platt LJ, Weintraub JA, Soobader MJ, Bramlett MD, Newacheck PW. Influences on children's oral health: A conceptual model. Pediatrics 2007; 120(3):e510-20. [ Links ]

8. de Almeida Pinto-Sarmento TC, Abreu MH, Gomes MC, de Brito Costa EM, Martins CC, Granville-Garcia AF, Paiva SM. Determinant factors of untreated dental caries and lesion activity in preschool children using ICDAS. PloS one. 2016; 11(2):e0150116. [ Links ]

9. Gussy MG, Waters E, Kilpatrick NM. A qualitative study exploring barriers to a model of shared care for pre-school children's oral health. British Dental Journal 2006; 201(3):165. [ Links ]

10. Kwan SY, Petersen PE, Pine CM, Borutta A. Health-promoting schools: an opportunity for oral health promotion. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2005; 83(9): 677-85. [ Links ]

11. 11. Jürgensen, N, Petersen, P. Promoting oral health of children through schools-Results from a WHO global survey 2012. Community Dent Health 2013; 30(4):204-18. [ Links ]

12. Haleem A, Khan MK, Sufia S, Chaudhry S, Siddiqui MI, Khan AA. The role of repetition and reinforcement in school-based oral health education-a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2015; 16(1):2. [ Links ]

13. Macnab, A, Kasangaki, A. 'Many voices, one song': a model for an oral health programme as a first step in establishing a health promoting school. Health Promotion International 2012; 27(1):63-73. [ Links ]

14. Monse, B, Benzian, H, Naliponguit, E, Belizario, V, Schratz, A, van Palenstein Helderman, W. The fit for school health outcome study - a longitudinal survey to assess health impacts of an integrated school health programme in the Philippines. BMC Public Health 2013; 13(1), 1-10. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-256. [ Links ]

15. Reddy, M, Singh, S. Viability in delivering oral health promotion activities within the Health Promoting Schools Initiative in KwaZulu-Natal. South African Journal of Child Health 2015b; 9(3):93-7. [ Links ]

16. Lawal, FB, & Taiwo, JO. An audit of school oral health education programme in a developing country. Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry 2014; 4 (Suppl. 1):S49. [ Links ]

17. Darlington EJ, Violon N, Jourdan D. Implementation of health promotion programmes in schools: an approach to understand the influence of contextual factors on the process. BMC Public Health 2018; 18(1):163. [ Links ]

18. Department of Health 2017. National Health Act 2003: National Health Insurance Policy: Towards Universal Health Coverage. Available: www.health.gov.za/index.php/component/phocad-ownload/category/382. Accessed 19 July 2018. [ Links ]

19. Matsoso MP, Fryatt RB: National Health Insurance: The first 18 months. South African Medical Journal 2013; 103(3):156-8. [ Links ]

20. Department of Health & Basic Education. Integrated School Health Policy. Health Basic Education Policy Document 2012; 1-42. [ Links ]

21. Thomson WM, Poulton R, Milne BJ, Caspi A, Broughton JR, Ayers KM. Socioeconomic inequalities in oral health in childhood and adulthood in a birth cohort. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 2004; 32(5):345-53. [ Links ]

22. Moore, G F, Audrey, S, Barker, M, Bond, L, Bonell, C, Hardeman, W., Wight, D. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council Guidance. British Medical Journal 2015; 350:h1258. [ Links ]

23. Ganief A, Thorpe J. City of Tshwane General & Regional Overview. Research Unit. Parliament of the Republic of South Africa. Available in: http://www.parliament.gov.za/content/TshwaneGeneral_and_Regions_Report_2013. Accessed 04 February 2018. [ Links ]

24. Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey (2013). Retrieved from South Africa: www.statssa.gov.za. [ Links ]

25. World Health Organisation. Oral Health Surveys Basic Methods. Geneva: WHO (2013). [ Links ]

26. Katzenellenbogen, J, Joubert, G. Data collection and measurement. In G. Joubert & R. Ehrlich (Eds.), Epidemiology: A research manual for South Africa (pp. 106-123). South Africa: Oxford University Press, 2007. [ Links ]

27. Shanbhog R, Godhi BS, Nandlal B, Kumar SS, Raju V, Rashmi S. Clinical consequences of untreated dental caries evaluated using PUFA index in orphanage children from India. Journal of International Oral Health 2013; 5(5):1. [ Links ]

28. Jong, A. Dental Public Health and Community Dentistry: CV Mosby (1981). [ Links ]

29. Bratthall D, Introducing the Significant Caries Index together with a proposal for a new global oral health goal for 12-year-olds. International Dental Journal 2000; 50:378-84. [ Links ]

30. Postma TC, Ayo-Yusuf OA, Wyk PJ. Socio-demographic correlates of early childhood caries prevalence and severity in a developing country - South Africa. International Dental Journal. 2008; 58(2):91-7. [ Links ]

31. Shaffer JR, Wang X, McNeil DW, Weyant RJ, Crout R, Marazita ML. Genetic susceptibility to dental caries differs between the sexes: a family-based study. Caries Research 2015; 49(2):133-40. [ Links ]

32. Lukacs JR, Largaespada LL. Explaining sex differences in dental caries prevalence: Saliva, hormones, and "life-history" etiologies. American Journal of Human Biology. 2006; 18(4): 540-55. [ Links ]

33. Bourne LT, Lambert EV, Steyn K. Where does the black population of South Africa stand on the nutrition transition?. Public Health Nutrition 2002; 5(1a):157-62. [ Links ]

34. Potgieter C, Naidoo S. How effective are resin-based sealants in preventing caries when placed under field conditions? South African Dental Journal 2017;72(1):22-7. [ Links ]

35. Yengopal V, Mickenautsch S, Bezerra AC, Leal SC. Caries-preventive effect of glass ionomer and resin-based Assure sealtants on permanent teeth: a meta-analysis. Journal of Oral Science 2009; 51(3):373-82. [ Links ]

36. Hooley M, Skouteris H, Boganin C, Satur J, Kilpatrick N. Parental influence and the development of dental caries in children aged 0-6 years: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Dentistry. 2012; 40(11): 873-85. [ Links ]

37. Kolisa Y. Assessment of oral health promotion services offered as part of maternal and child health services in the Tshwane Health District, Pretoria, South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine 2016; 8(1):1-8. [ Links ]

38. Watt RG. Strategies and approaches in oral disease prevention and health promotion. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2005; 83(9):711-8. [ Links ]

39. Bajomo AS, Rudolph MJ, Ogunbodede EO. Dental caries in six, 12 and 15 year old Venda children in South Africa. East African Medical Journal 2004; 81(5):236-43. [ Links ]

40. O'Callaghan PM, Allen KD, Powell S, Salama F. The efficacy of non-contingent escape for decreasing children's disruptive behaviour during restorative dental treatment. Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis 2006; 39(2):161 -71. [ Links ]

41. Singh S. Dental caries rates in South Africa: implications for oral health planning. Southern African Journal of Epidemiology and Infection 2011; 26(4):259-61. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Mpho M Molete

Community Dentistry, School of Oral Health Sciences

Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

Yale Road, Parktown, 2193

Tel: +27 (0)64 752 3860

Email: mpho.molete@wits.ac.za