Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562

Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.73 n.9 Johannesburg Oct. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2018/v73no9a2

RESEARCH

Testing Gustafson's dental age estimation method on a sample of Western Cape adults

S ChandlerI; VM PhillipsII

IBChd (UWC), PDD (Endo) (UWC), MSc (Forensic Dent), Department of Oral Pathology and Forensic Sciences, Faculty of Dentistry, University of the Western Cape

IIBDS (Wits), MChD (Stell), FC Path SA (Oral Path), Dip Max-Fac Radiology, PhD (UwC), DSc (UWC)), Professor, Department of Oral Pathology and Forensic Sciences, Oral Health Centre, Faculty of Dentistry, University of the Western Cape

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Teeth are often used to assist in the identification of human bodies after death, especially in cases where the body is badly burned or decomposed. Age estimation can play a significant role in helping narrow down the spectrum of possible identities. Gustafson created a method of dental age estimation, using six age-related changes of teeth that occur after the eruption of the dentition. This age estimation method has been used on unidentified individuals at the Salt River and the Tygerberg Medico-Legal Laboratories. However, it may be questionable as to whether the method is accurate when applied to the population of the Western Cape

AIM: The aim of this study was to test the accuracy of Gustafson's method on a sample of adult teeth from the Western Cape, of known chronological age

METHODS: Extracted mandibular central and lateral incisors and maxillary central incisors were used in this study. Two examiners independently used Gustafson's method to estimate the ages of the donors of the teeth

CONCLUSION: This method was found to be inaccurate when applied to a sample of the adult population of the Western Cape

Keywords: forensic dentistry, age estimation, teeth

INTRODUCTION

Age estimation is an important part of forensic dentistry. The use of teeth for this purpose can play a significant role in the process of identifying a human body after death, especially in cases where the body is badly burnt or decomposed, as teeth are usually preserved for a long period of time, even after most of the other tissues have disintegrated. Identification is usually undertaken by comparison of ante-mortem and postmortem dental records, when the identity of the deceased is suspected. In some cases, however, when the identity of the body is not known, age estimation can play a significant role in narrowing down possible identities which are culled from the Missing Persons database.1,2

Teeth continue to show several different age-related changes, even after the formation and development of the dentition is complete. These changes can be used to estimate the individual's chronological age. The tooth changes used in the Gustafson method (1950) include attrition, change of the level of the periodontal attachment, secondary dentine deposition, resorption of the root, apposition of cementum and translucency of the root.4-7

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

In the past, several different techniques have been suggested for the estimation of a person's dental age, based on the facial and/or oral structures. These include morphological and radiological methods.

Some of the techniques can also be classified as invasive, which can mostly be used only in deceased individuals, and others as non-invasive, which can be used in both the living and the dead.6

Gustafson's method (1950) used the six age-related changes mentioned above.7 Gustafson then applied his method to teeth that had been extracted from persons of known age. He used ground sections of 1.0 mm thickness to determine the translucency of the root dentine and ground sections of 0.25 mm thickness to determine the remaining Ave factors.

Each of these changes in a specific tooth was then rated and given a value between 0 and 3. The sum of the values of each change of each tooth, combined with the age of the individual (from whom the tooth had been extracted) was then used to create a regression line. From this graph, the age of an unknown individual was then determined with reasonable accuracy.1, 6, 7

According to Gustafson, the average error in age estimation using this technique was about 3.63 years. He then also found that the estimation of an individual's age is even more accurate if more than one tooth from that individual were examined. This study was however done only on Europeans from Sweden.1, 6, 7

Over the years numerous studies have been conducted in order to either prove or disprove Gustafson's method of age estimation, as several researchers and investigators were convinced that there was an error in this method.

Some of these researchers were of the opinion that Gustafson based his method on several assumptions that were most likely incorrect.8-10 He assumed that these six criteria were all equally accurate and effective in the process of age estimation and that the rates at which the individual criteria change are equal, resulting in his method of just adding the data together.8-10

Gustafson also assumed that the age information obtained from the six different criteria is statistically independent, which has been shown to be inaccurate.8-10

The six criteria used in Gustafson's method of age estimation are also influenced by several different factors (other than aging) and can even have an influence on each other, which Gustafson did not consider. These include the following:

Attrition can be influenced by bruxism, diet, morphology of the teeth and dental arches, the direction and force of masticatory movements and the number of teeth present in the mouth.11-13

Secondary dentine can be influenced by attrition, abrasion, periodontal disease and mechanical injury or irritation caused by dental procedures and caries.14

Periodontal attachment level can be influenced by peri-odontal disease.13

Cementum apposition can be influenced by periapical periodontitis, root resorption and whether or not the tooth is in function.13

Root resorption can be influenced by dental trauma, periapical periodontitis, excessive forces including mechanical forces applied by orthodontic appliances and occlusal forces, hormonal imbalances and pressure from impacted teeth or benign neoplasms that press on the roots of adjacent teeth.13,14

Translucency can be influenced by periodontal infection and diseases of the pulp of the tooth.15 As a result of these incorrect assumptions and additional influencing factors, most of the subsequent studies have proved the Gustafson method faulty, and have resulted in several modifications to the original method.4, 8, 16-19

Many studies have been performed over the years in order to either prove or disprove this method of age estimation. These were undertaken in several different countries including Sweden (Gustafson, 1950),7 Scandinavia (Bang and Ramm, 1970; Johanson, 1971),8, 16 France (Haertig et al., 1985),21 Limpopo, South Africa (Nkhumeleni et al., 1989),22 Australia (Richards and Millar, 1991),23 Germany (Lampe and Roetzscher, 1994),24 China (Li an Ji, 1995),25 England (Lucy et al., 1995),26 America (Pigno et al., 2001),27 Iran (Monzavi et al., 2003)18 and India (Rai et al., 2006; Shrigiriwar and Jadhav, 2013).2,28 None were conducted in the Western Cape, in South Africa.

The Western Cape has a population constituting numerous ethnic groups and cultures. A wide diversity in socio-economic circumstances, eating habits, oral hygiene habits and smoking habits also exist, which can all play a role in the age-related changes of a tooth.

This leads to the question: Is Gustafson's method of age estimation of teeth accurate when applied to the people of the Western Cape?

The aim of this study was to determine the accuracy of Gustafson's method of age estimation of adult teeth when applied to a sample of the adult population of the Western Cape.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Caries-free central and lateral mandibular incisors (FDI tooth numbers 32, 31, 41 and 42) and maxillary central incisors (tooth numbers 11 and 21) were collected from the University of the Western Cape Oral Health Centre at Tygerberg Hospital.

These teeth had been extracted as part of routine dental treatment, which resulted in only a limited number of teeth being available for the study. An additional source of teeth was from cadavers of known chronological age (after dissection by medical students), used in the Anatomy and Histology Department of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences of the University of Stellenbosch.

A total of 55 teeth was used to conduct the study. The teeth were from persons between the ages of 21 and 76 years. Carious teeth, restored teeth, endodontically treated teeth and teeth that presented with either crown or root fractures were excluded from the study.

Details regarding the date of birth, date of death, sex and ethnic group of each cadaver were obtained from the death certificates. The anatomy registration numbers were used to identify the teeth collected from the cadavers. Teeth collected from patients were given random numbers. The teeth were sectioned in the long axis of the tooth (from the labial surface to the lingual surface), using the Isomet circular saw (Figure 1). The thickness of each section was standardized at 100μm.

The tooth sections were subsequently mounted on glass microscope slides, embedded in DPX® (from Leica Microsystems)29 and covered with a glass cover slip (Figure 2).

Age estimation of each tooth was then undertaken independently by two examiners using the Gustafson's method. Using this method, the degree of attrition, change of the level of periodontal attachment, the extent of secondary dentine deposition within the pulp, the apposition of cementum, the resorption of the root and the transparency or translucency of the root were given a value for each tooth.

The range of the values was between 0 and 3, with the value 0 meaning the change is not present, and 3 meaning the change is severe.1,6,7 The regression line compiled by Gustafson was then used to estimate the age of the individual from whom the tooth had been extracted. The examiners were blinded as to the chronological age of the individual from whom the tooth derived.

The chronological age was revealed only at this stage and was compared with the estimated age value. The results of the comparisons were statistically analyzed to determine the degree of accuracy of the Gustafson's method of age estimation.

RESULTS

A total of 55 teeth were used to conduct the study. Of these, 52 had been harvested from cadavers and three teeth extracted from live patients. The age range of the tooth donors was between the ages of 21 and 76 years.

The mean age of the sample was 45 years. Sixteen (16) of the donors were female and 39 were male. Thirty-nine (39) of the donors were of the Coloured ethnic group of the Western Cape, 14 of the Black ethnic group and only two of European origin.

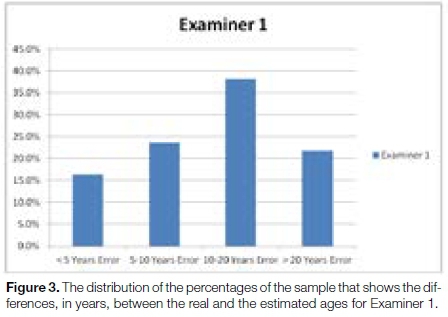

When the estimated ages as calculated by Examiner 1 (using Gustafson's method of age estimation) were compared with the chronological (real) ages of the donors, none were entirely accurate: 16.4% of the cases showed a difference of less than 5 years between the estimated and real ages, 23.6% a difference of between 5 and 10 years, 38.2% a difference between 10 to 20 years and 21.8% showed a difference of more than 20 years (Figure 3).

The mean of the differences (average error) between the real and estimated ages (for Examiner 1) was 13.7 years. The median was 13.0 years and the standard deviation was 9.38 years.

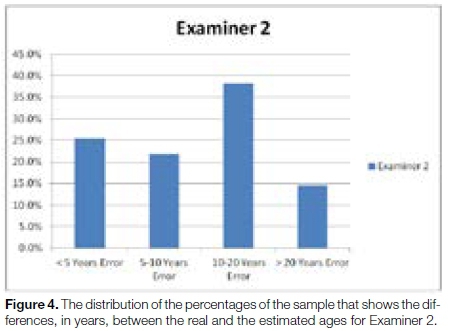

When the estimated ages as calculated by Examiner 2 (using Gustafson's method of age estimation) were compared with the chronological (real) ages of the donors, none were entirely accurate: 25.5% of the cases showed a difference of less than 5 years between the estimated and real ages, 21.8% a difference of between 5 and 10 years, 38.2% a difference between 10 to 20 years and 14.5% showed a difference of more than 20 years (Figure 4). The mean of the differences (average error) between the real and estimated ages (for Examiner 2) was 11.6 years. The median was 10.5 years and the standard deviation was 8.52 years.

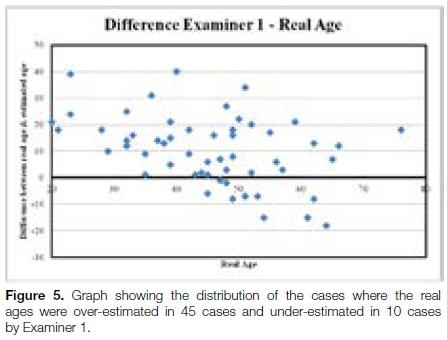

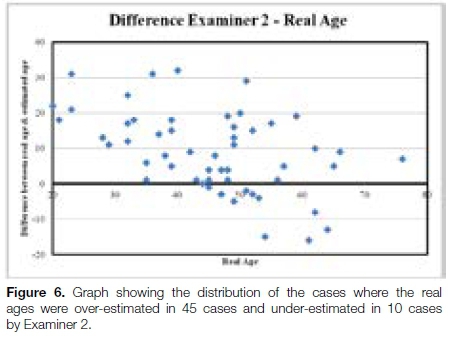

When examining the scatter plots (Figures 5 and 6) showing the difference between the real ages and the estimated ages on the one axis, and the real ages on the other axis, it becomes clear that the ages were overestimated in most cases by both Examiners 1 and 2. The ages were over-estimated in all the cases where the donors were younger than 45 years of age. It is only in donors 45 years of age and older that both Examiners 1 and 2 under-estimated the ages in 10 cases.

Using the Student's t-test and p-value30, 31 to compare the mean differences between the estimated ages and real ages as found by Examiners 1 and 2, it was established that there was not a statistically significant difference between the results found by Examiners 1 and 2, the p-value being greater than 0.05.

Using the Student's t-test and p-value30, 31 to compare the mean differences between the estimated ages and real ages as found by Examiners 1 and 2 with Gustafson, it was established that there was a statistically significant difference between the results found by Examiners 1 and 2 compared with Gustafson, as the p-value < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The criteria used in Gustafson's method of age estimation are influenced by several different factors including bruxism, diet, number of teeth present in mouth, oral health and habits, orthodontic and occlusal forces and hormonal imbalances.11-14

All these factors that may possibly affect the different criteria, may result in an inaccurate estimated age. As most of the teeth used in this study were harvested from cadavers, it is impossible to know the specific individual's diet, habits, life style and medical history.

These different factors, together with the inaccurate assumptions made by Gustafson, may be the reason why there is such a major difference in this study between the estimated ages calculated by using Gustafson's method of age estimation and the individual's real age. Bajpai, who replicated Gustafson's method of age estimation, excluded all patients with a history of traumatic occlusion, any drug or medical history and those with abnormal teeth or oral habits. As a result, the differences found in the study by Bajpai (2011) between the estimated and real ages were much smaller than the difference found in our study.32

The mean difference (average error) between the estimated ages and the chronological ages was 13.7 years for Examiner 1 and 11.6 years for Examiner 2, with standard deviations of 9.38 years and 8.52 years respectively. Gustafson claimed that the average error in age estimation using this technique was about 3.63 years.7

There is clearly a statistically significant difference between the average error claimed by Gustafson and those found in this study (p-value < 0.05). The results found in this study are also different from those found in other similar studies that were recently done by Bajpai (2011), who found a mean difference of 4.86 years between the estimated and chronological ages and Shrigiriwar and Jadhav (2013) who found a mean difference of ± 4.43 year.28, 32

This study found that the ages were over-estimated in most cases by both Examiner 1 and 2, especially when the donors were younger than 45 years of age. In donors 45 years of age and older, the ages were under-estimated in ten cases.

This is consistent with the results found by Solheim and Sundnes (1980) who found that over-estimation of ages occurred mostly in individuals younger than 40 years and under-estimation in individuals older than 50 years of age.33

Mandibular central incisors usually erupt between the ages of 6-7 years. Mandibular lateral incisors and maxillary central incisors usually erupt between the ages of 7-8 years.34 These permanent teeth would have been present in the mouth for the longest period, and would presumably give the most accurate results when used in age estimation.

Other studies have, however, used several different teeth and have obtained much more accurate results than those found in this study. These include studies done by Maples (1978) who used second molars, Monzavi et al. (2003) who used first premolars and Bajpai (2011) who used canines, premolars and incisors (in order of preference).9, 18, 32

Although the differences between the results found by Examiner 1 and Examiner 2 were not statistically significant (p > 0.05), a method that uses scientific devices to accurately measure the different criteria used in Gustafson's method of age estimation needs to be developed, which may contribute toward even more uniform results.

The limitations of this study included the small sample size and the relatively small demographic area in which the teeth were collected. The small sample size was however due to the very strict exclusion criteria.

The sample size (55 teeth) in this study was larger than the sample originally used by Gustafson (41 teeth) and that used recently by Bajpai (20 teeth).7,32 Further studies are therefore necessary which will ideally consist of a larger sample size and a wider demographic area in which the teeth are collected.

The results found support the hypothesis and prove that Gustafson's method of age estimation is not applicable for the adult population of the Western Cape.

CONCLUSION

Gustafson's method of age estimation was derived more than 60 years ago and was based only on Europeans. The present study was undertaken to test the hypothesis that the age estimation of Gustafson was not applicable to the population of the Western Cape.

The results showed that Examiner 1 and Examiner 2 over-estimated the ages of 45 of the 55 individuals. All the cases where the ages were under-estimated were of individuals who were over 45 years of age.

The difference between the results found by Examiner 1 and Examiner 2 were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The results of the two independent examiners were found to be consistently and uniformly inaccurate when attempting dental age estimation of the sample.

REFERENCES

1. Metzer Z, Buchner A, Gorsky M. Gustafson's method for age determination from teeth - a modification for the use of dentists in identification teams. Journal of Forensic Sciences 1980; 25(4): 742-49. [ Links ]

2. Rai B, Dhattarwal SK, Anand SC. Five markers of changes in teeth: an estimating of age. The Internet Journal of Forensic Science 2006; Vol. 1, No. 2. [ Links ]

3. Vystrcilova M, Novotny V. Estimation of age at death using teeth. Variability and Evolution 2000; 8: 39-49. [ Links ]

4. Burns KR, Maples WR. Estimation of age from individual adult teeth. Journal of Forensic Sciences 1976; 21:343. [ Links ]

5. Singh A, Gorea RK. Age estimation by Gustafson's method and its modifications. J Indo Pacific Acad Forensic Odontol. 2010; 1(1): 12-9. [ Links ]

6. Willershausen I, Forsch M, Willershausen B. Possibilities of dental age assessment in permanent teeth: a review. Dentistry 2012; S1:001. doi: 10.4172/2161-1122.S1-001. [ Links ]

7. Gustafson G. Age determination on teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1950; 41: 45-54. [ Links ]

8. Johanson G. Age determination from teeth. Odontologist. Revy. 1971; 22: supplement 21: 1-126. [ Links ]

9. Maples WR. An improved technique using dental histology for the estimation of adult age. Journal of Forensic Sciences 1978; 23: 764-70. [ Links ]

10. Senn DR, Stimson PG, editors. Forensic Dentistry. Second Edition. Boca Raton. CRC Press; 2010: 281-84. [ Links ]

11. Richards LC, Brown T. Dental attrition and age relationships in Australian Aboriginals. Archaeology in Oceania 1981; 16(2): 94 - 8. [ Links ]

12. Ekfeldt A, Hugoson A, Bergendal T, Helkimo M. An individual tooth wear index and an analysis of factors correlated to incisal and occlusal wear in an adult Swedish population. Acta Odontol Scand. 1990; 48(5): 343-9. [ Links ]

13. Cawson RA, Odell EW, editors. Cawson's Essentials of Oral Pathology and Oral Medicine. Seventh edition. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2002: 62-65, 69-89. [ Links ]

14. Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE, editors. Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology. Second edition. United States of America. W.B. Saunders Company; 2002: 59, 110. [ Links ]

15. Singhal A, Ramesh V, Balamurali PD. A comparative analysis of root dentin transparency with known age. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2010; 2(1): 18-21. [ Links ]

16. Bang G, Ramm E. Determination of age in humans from root dentine transparency. Acta Odontol Scand. 1970; 28:3-35. [ Links ]

17. Maples WR, Rice PM. Some difficulties in the Gustafson's dental age estimations. Journal of Forensic Sciences 1979; 24 (1): 168-72. [ Links ]

18. Monzavi BF, Ghodoosi A, Savabi O, Hasanzadeh A. Model of the age estimation based on the dental factors of the unknown cadavers among Iranians. Journal of Forensic Sciences 2003; 18 (2): 379-81. [ Links ]

19. Singh A, Gorea RK, Singla U. Age estimation from the physiological changes of teeth. J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 2004; 26: 94-6. [ Links ]

20. Lamendin H, Baccino E, Humbert JF, Tavernier JC, Nossintchouk RM, Zerilli A. A simple technique for age estimation in adult corpses: the two criteria dental method. Journal of Forensic Sciences 1992; 37(5): 1373-9. [ Links ]

21. Haertig A, Crainic K, Durigon M. Medicolegal identification by the dental system. Presse Med. 1985; 14 (9): 543-5. [ Links ]

22. Nkhumeleni FS, Raubenheimer EJ, Monteith BD. Gustafson's method for age determination, revised. The Journal of Forensic Odonto-Stomatology 1989; 7(1): 13-6. [ Links ]

23. Richards LC, Millar SL. Relationships between age and dental attrition in Australian aboriginals. American Journal Phys Anthropology. 1991; 84 (2): 159-64. [ Links ]

24. Lampe H, Roetzscher K. Age determination from adult human teeth. Forensic Odontology 1994; 14:165-7. [ Links ]

25. Li C, Ji G. Age estimation from the permanent molars in Northern China by the method of average stage of attrition. Forensic Science International Journal 1995; 75 (2-3): 189-96. [ Links ]

26. Lucy D, Pollard AM, Roberts CA. A comparison of three dental techniques for estimating age at death in humans. Journal of Archaeological Science 1995; 22: 417-28. [ Links ]

27. Pigno MA, Hatch JP, Rodrigues-Garcia RC, Sakai S, Rugh JD. Severity, distribution and correlates of occlusal tooth wear in a sample of Mexican-American and European-American adults. International Journal Prosthodont. 2001; 14 (1): 65-70. [ Links ]

28. Shrigiriwar M, Jadhav V. Age estimation from physiological changes of teeth by Gustafson's method. Med Sci Law. 2013; 53(2): 67-71. [ Links ]

29. Leica Microsystems: Manufacturers and distributors of DPX Mounting Media & Section Adhesive. [ Links ]

30. Deacon J. The Really Easy Statistics Site. Edinburgh; accessed 2013. [Online] Available from: http://www.archive.bio.ed.ac.uk/jdeacon/statistics/tress4a. [ Links ]

31. Lowry R. Concepts and Applications of Inferential Statistics. New York; 1999-2013 [Online]. Available from: http://www.vassarstats.net/textbooks/ch11pt1. [ Links ]

32. Bajpai M. Age estimation using physiological changes of teeth. European Journal of Experimental Biology 2011; 1(4): 104-8. [ Links ]

33. Solheim T, Sundnes PK. Dental age estimation of Norwegian adults - a comparison of different methods. Forensic Science International Journal 1980; 16(1): 7- 13. [ Links ]

34. Nelson SJ, Ash M. Wheeler's Dental Anatomy, Physiology and Occlusion. Ninth edition. St. Louise, Missouri, Elsevier Saunders; 2010: 31. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Susan Chandler

Department of Oral Pathology and Forensic Sciences, Oral Health Centre, Fransie van Zijl Avenue

Parow Valley, 7505

Email: ssnchndlr@gmail.com