Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562

Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.73 n.8 Johannesburg Sep. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2018/v73no8a5

RESEARCH

Oral health status of sentenced offenders in KwaZulu-Natal province

M RadebeI; S SinghII

IBachelor of Dental Therapy (UDW); MBA (MANCOSA); Dip Project Management (DAMELIN). HPCSA, SADTA, BHF. Tel: +27 31 373 5800. Email: mbuyiselwar@dut.ac.za, Cell: 0711886265

IIB.OH (UDW), M.Sc[DENT], PhD (UWC), PG Dip Heal Res Ethics (Stell), Associate Professor, Discipline of Dentistry | Health Sciences | College of Health Sciences. Chair: Humanities and Soc Sc Res Ethics Com. Tel: +27 31 260 8591 Email: singhshen@ukzn.ac.za, Address: 4th Floor F Block, Westville Campus, University Road, Durban. Website: chs.ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: To assess the oral health status, knowledge, attitude and practice of sentenced offenders in KwaZulu-Natal correctional centres

METHODS: Simple random sampling selected 373 offenders from nine correctional centres in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Data were collected using a closed-ended structured questionnaire, collated and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24

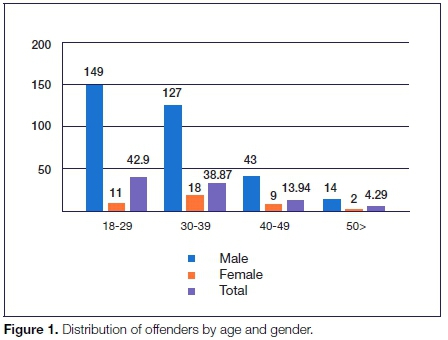

RESULTS: One hundred and sixty-one (43.2%) were aged 18-29, 144 (38.6%) in age group 30-39, 52 (13.9%) in group 40-49 and 16 (4.3%) were older than 50 years. Over two thirds of the study participants (72.7%) reported brushing teeth twice daily

Oral health was perceived as poor by 292 (78.3%) offenders. Common self-reported dental problems were caries, bleeding gums, loose teeth and sensitive teeth. Cigarette smoking was prevalent and relatively high among offenders older than 50 years.

CONCLUSION: Special attention is required from the Department of Correctional Services and the public oral health sector to meet the basic oral health needs of this population. A preventive-oriented oral health care system can synergistically complement other existing services offered in correctional facilities such as the smoking cessation programme. The prevalence of oral diseases of this vulnerable population can be drastically reduced

INTRODUCTION

Numerous studies conducted in correctional centres in South Africa, India and United Kingdom have shown that prisoners have poor oral health conditions, particularly reflected in the high number of lost and untreated decayed teeth.1,2

In addition to this, the health status of prisoners is not usually incorporated into data and reports that summarize the state of the nation's health, leading to a lack of planned health services for them by the relevant health bodies.3

The available research indicates that most correctional institutions are failing to provide effective and consistent care to offenders under constraints such as security restrictions and resource availability.4 The inability to offer consistent care to offenders is further exacerbated by overcrowding which has been identified as a feature of most centres worldwide and continues to pose a major challenge for the relevant Department of Correctional Services.5

The South African Department of Correctional Services (DCS) reported at the end of the 2015/2016 financial year that the total inmate population was 161,984, with an approved bed space of 119,134, which translated to an occupancy rate of 135.96%. Of the total, 72.06% were sentenced offenders and 27.94% were un-sentenced offenders.

Currently, in KwaZulu-Natal province there are 42 correctional centres with an actual inmate population of 29,253 and an approved bed space of 16,550, which translates into 176.176% occupancy rate.5

Clearly, South African correctional institutions are overcrowded. Given the challenges associated with overcrowding, the Department of Correctional Services in SA is plagued by an acute paucity of information reporting on the oral health status of offenders.1 The only available dental research involving offenders is a baseline survey which was conducted in the Western Cape Correctional centres. Currently, there are no available data on oral health records for sentenced offenders in KwaZulu-Natal province.

Therefore, this study was conducted with an aim of assessing the oral health status, oral health knowledge, attitude and practice of sentenced offenders in KwaZulu-Natal correctional centres.

METHODS

This study was quantitative in design. The sample comprised incarcerated offenders (n=373) who were randomly selected from nine correctional institutions located within the following district municipalities of KwaZulu-Natal province (Zululand, uMzinyathi, uThukela, uMgungundlovu, iLembe, eThekwini, Ugu and Sisonke).

Using a sample size calculator, a power calculation was done with a confidence level of 95%, a 5% margin of error and 0.415 standard deviation to determine an appropriate sample size (n=373).

Excluded from the study were sentenced offenders who were below 18 years of age and those who did not give consent to participate. A closed-ended structured questionnaire was administered to assess socio-demographic information; frequency of tooth brushing; type of dental treatment received during incarceration; self-perceived need for dental treatment; attitudes and behaviour scores among offenders regarding oral health; past/present dental attendance and treatment, and smoking prevalence among offenders.

Frequency of tooth brushing was scored on a 3-point scale, ranging from less than once a day to more than once a day (twice or three times). Type of treatment received during incarceration-variable was scored on a 6-point scale, ranging from extraction, Alling, scaling and polishing, crown and bridge, root canal to none.

Internal consistency was assessed using the Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficient which was considered adequate when α > .841 and all data analyses were conducted in SPSS version 24. Descriptive statistics was utilised to investigate any possible relationship between the variables.

When the distribution of scores of the outcome data did not approximate the normal distribution, a non-parametric statistical test viz. Kruskal-Wallis test, was conducted to investigate these relationships further. Statistical significance was noted only when the p-value was less than 0.05.

The Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (BE046/15) approved the study and ethical guidelines were followed to ensure confidentiality in the management of data. Gatekeeper permission was obtained from the Department of Correctional Services Research Ethics Committee.

Participants were given clear explanations about the purpose of the survey. All the sentenced offenders aged 18-75 years who were willing to give consent were eligible to participate in the study.

After obtaining permission from the correctional service authorities and participants, the general demographic information data, which included variables such as gender, age and race of the sample were collected by the researcher. The questionnaire was piloted with 37 participants in Greytown Correctional Centre who were later excluded from the main study.

RESULTS

A total of 373 study participants were recruited in the survey, 333 (89.28%) being male and 40 (10.72%) female. The overall response rate was 100 per cent.

Ninety-eight percent of the participants (n=364) described themselves as black and the remainder comprised coloureds (n=5) and individuals from Caucasian (n=2), Indian (n=2) backgrounds.

Two hundred and eleven participants (56.6%) were incarcerated in correctional centres located in urban areas, one hundred and seven participants (28.7%) in peri-urban areas and fifty-five (14.7%) participants in rural areas. Distribution of the offenders according to age and gender is presented in Figure 1 (below).

Table 1 (p516) depicts the distribution of attitudes and behaviour scores among offenders in KwaZulu-Natal correctional centres regarding oral health. Generally, 68.3% of 18-29 year-olds and 93% of participants older than 50 years brushed their teeth at least once a day. About 76.7% of offenders incarcerated in urban areas brushed their teeth at least twice a day, while 65.5% offenders in rural areas practiced the same pattern, a less frequent practice when compared with urban offenders.

Overall, more than two thirds of the study participants (72.7%) reported brushing their teeth twice daily. Response to questions about the utilisation of dental health care services before incarceration revealed that 236 participants (63.3 %) could be regarded as regular users of the dental facilities, while 137 (36.7%) participants had not seen a dentist at all in their communities.

Of those who had visited the dentist, 34 (9.1%) had had their last dental consultation more than Ave years ago. A recent dental visit was more often reported among participants older than 50 years (43.8%), a statistic slightly higher than for the 18-29 year-olds, which was at 42.2%. Regarding the service availability and access during incarceration, more than two thirds of the study sample 238 (63.8%) reported that it was difficult to obtain a dental appointment due to a long waiting list. Table 2 (p517) illustrates the utilisation of dental services in correctional centres among the offenders. The results reveal that the participants held in rural correctional centres had higher extraction rates (78.2%) when compared with peri-urban (66.4%) and urban centres (73.5%).

A total of 203 (54.4%) study participants were generally satisfied with the services they had received in the correctional centres. It was noted that there were no oral health educational programmes offered to the participants in any of the centres across KZN province.

The results of the current study also revealed that a total of 292 (78.3%) offenders perceived their oral health as poor and the common self-reported dental problems experienced in correctional centres were dental caries, bleeding gums, loose teeth and sensitive teeth. Lastly, the age group stratification revealed that participants older than 50 years had more dental caries, loose teeth and sensitive teeth than did 18-29 year-olds.

The distribution of study participants according to smoking status is shown in Table 3 (p516). A total of 249 (66.8 %) participants reported they were regular smokers. When smoking patterns were further analysed it was discovered that this habit was relatively high (75%) among participants older than 50 years and decreased to 64.6% among 18-29 year-olds. Lastly, it was observed that only 9.4 % of the regular smokers had attempted to quit smoking and 58.2% did not have a specific reason to quit, as they were still smoking.

DISCUSSION

This cross-sectional study provides a unique opportunity for analysing the state of oral health care services and prevention interventions provided by correctional facilities in KwaZulu-Natal. Participants in this study were stratified into subgroups and differentiated based on traits that were considered relevant by the researchers such as gender, race and age. In the study sample, males were significantly over-represented.

Harlow6 showed that prison inmates are demographi-cally different from their non-incarcerated counterparts. By gender, male inmates tend to be overrepresented (96 percent); by racial category, ethnic groups dominate the population (62 percent); and by age, younger adults outnumber the middle-aged group (66 percent).6

Similarly, a demographic analysis of inmate population by Sifunda et al. revealed that male offenders were alarmingly overrepresented in KZN correctional centres.7 Authors have argued that men commit a much higher percentage of the most serious and violent crimes and these crimes are most likely to lead to arrest and imprisonment and result in longer periods of imprisonment.8

Regarding oral hygiene practices, the majority of the respondents in the present study reported brushing their teeth twice or three times a day. This is comparable to results obtained in a study conducted by Vainionpää et al., where twice a day tooth brushing seemed to be an established practice.9

Despite the fact that the majority of the study participants stated that they were brushing their teeth more frequently, it was noted that more than two thirds reported that they were suffering from gingival bleeding and untreated dental caries. This finding is in agreement with a study which was conducted by Akaji and Ashiwaju who found that caries experience of offenders incarcerated at Enugu Federal Prison in Nigerian correctional centre was high and their periodontal health was compromised.10

Regarding the use of dental services, less than a third of the participants reported that they had never seen a dentist in their lives. Of those who had consulted with a dentist, the main reasons for such appointments were seeking emergency dental services such as dental extractions and pain relief.

This trend was observed in a study conducted by Nobile et al., where incarcerated offenders had one or more teeth extracted due to caries, the process continuing and eventually rendering a large number of subjects edentulous.11

In the present study, cigarette smoking was prevalent among study participants and it was discovered that this habit was relatively high among offenders older than 50 years. Similar trends have been observed in a study conducted by Akaji and Folaranmi which involved offenders of the Nigerian Federal prison in Enugu.12

Tobacco use by prison inmates is quite common, indeed is an integral part of their life. It serves a range of functions in prison; as a surrogate currency, a means of social control, as a symbol of freedom in a group with few rights and privileges, a stress reliever, and as a social lubricant.13

The use of tobacco has been associated with, loss of periodontal attachment, increased pocket depths, loss of alveolar bone and higher rates of tooth loss.14 It is therefore incumbent upon officials representing Correctional Services to strengthen smoking cessation programmes in correctional institutions in order to circumvent the negative effects of smoking among this disadvantaged population.

Regarding oral health promotion programmes, most respondents pointed out that there were no such organised programmes in the correctional centres in KwaZulu Natal. The study conducted by Sifunda et al., in South African correctional centres highlighted prevention programmes as an area that required stronger emphasis to facilitate imparting skills to inmates.7

Although, Sifunda et al. made recommendations to the DCS to pay special attention to the preventive healthcare programmes in order to improve the lives of offenders during incarceration, the current study found that preventive programmes were largely non-existent in correctional centres across KZN as perceived by all study participants. This could partly be attributed to the fact that most correctional centres are constructed to maximize public safety, not to efficiently deliver health care.15

Furthermore, prison health services often have small budgets.16 In most Correctional Services facilities, the majority of dental attention is provided on a part-time basis under various contractual arrangements. Prison warders who have no health-training act as the first point of consultation, approving and granting permission for inmates to see health workers.7 This subjectivity could potentially compromise access to health care for some inmates.17 Some prisoners are assessed as being a threat to the security, safety or order of the prison system and are deemed to be a higher risk than the rest of the prisoner population.18

As prisons put security as a top priority most staff deployment decisions will be geared towards ensuring that safety is maintained at all times and that could mean that escorting sick inmates receives lower priority.7 This situation means that some inmates are more likely to be disadvantaged with respect to accessing dental care.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Although findings from this study have important practical and political implications, several limitations should be noted. A major limitation of the study was its cross-sectional nature, which limited the ability to relate the time pattern with risk factors such as smoking and their complications on the oral health of the offenders.

Since this was self-reporting there could have been over-reporting due to the desire for social acceptance. More research is required to compare the self-reported data to the actual oral health status. The study reflects what is currently in place in KwaZulu-Natal correctional institutions and the findings clearly emphasise that there is an urgent need for the development of a comprehensive oral health preventive programme that will improve the oral health status of this disadvantaged community.

CONCLUSION

The study highlight the need for special attention from the Department of Correctional Services and public oral health sector to meet the basic oral health needs of this population. Preventive oral health care programmes should be planned for offenders in order to educate them with regard to proper oral hygiene practices as eventually many of them will be going back to their communities after serving time.

Therefore, there it is incumbent upon DCS to review its strategy from a curative oral health care to a more preventive approach. Basically, oral health promotion should be an essential part of health service provision in correctional institutions.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation and gratitude to the Department of Correctional Services for their assistance during this research project and would like to thank all the participants in the study who showed a lot of enthusiasm and cooperation.

ACRONYM

DCS: South African Department of Correctional Services

References

1. Naidoo S, Yengopal V, Cohen B. A baseline survey: oral health status of prisoners. Western Cape. SADJ. 2005; 60(1):24-7. [ Links ]

2. Reddy V, Kondareddy CV, Siddanna S, Manjunath M. A survey on oral health status and treatment needs of life-imprisoned inmates in central jails of Karnataka, India. Int Dent J. 2012; 62(1):27-32. [ Links ]

3. Treadwell HM, Formicola AJ. Improving the oral health of prisoners to improve overall health and well-being. Am J Public Health. 2005; 95:1677-8. [ Links ]

4. Walsh T, Tickle M, Milsom K, Buchanan K, Zoitopoulos L. An investigation of the nature of research into Dental Health in Prisons: A Systematic Review. British Dental Journal 2008; 204(12):683-9. [ Links ]

5. DCS. Annual Report 2015/2016 Financial Year. Department Correctional Services, Republic of South Africa: 2015. [ Links ]

6. Harlow CW. Education and correctional populations. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Bureau of Justice Statistics Washington, DC. 2003. [ Links ]

7. Sifunda S, Reddy PS, Braithwaite R, Stephens T, Ruiter RAC, van den Borne B. Access point analysis on the state of health care services in South African prisons: A qualitative exploration of correctional health care workers' and inmates' perspectives in Kwazulu-Natal and Mpumalanga. Social Science & Medicine 2006; 63(9):2301-9. [ Links ]

8. O' Neill P. Why are there many more men in prison than women in every single country? 2016. [ Links ]

9. Vainionpää R, Peltokangas, A., Leinonen, J., Pesonen, P., Laitala, M., Anttonen, V. Oral health and oral health-related habits of Finnish prisoners. BDJ Open. 2017. [ Links ]

10. Akaji EA, Ashiwaju MO. Oral health status of a sample of prisoners in Enugu: A disadvantaged population. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014; 4:650-3. [ Links ]

11. Nobile CG, Fortunato L, Pavia M, Angelillo I. Oral health status of the male prisoners in Italy. International Dental Journal 2007; 57:27-35. [ Links ]

12. Akaji E A, Folaranmi N. Tobacco use and oral health of inmates in a Nigerian prison. Niger J Clin Pract. 2013; 16: 473-7. [ Links ]

13. Butler T, Richmond R, Belcher J, Wilhelm K, Wodak A. Should smoking be banned in prison? Tob Control. 2007; 16:291-3. [ Links ]

14. Novak MJ, Novak KF. Newman, Takei and Carranza. Smoking and periodontal disease. Clinical Periodontology. 9th ed. 2003; 245. [ Links ]

15. Bick J. Infection control in jails and prisons. Clinical infectious diseases: An official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2007;45:1047-55. [ Links ]

16. Vieira AA, Ribeiro SA, Galesi VM, dos Santos LA, Golub JE. Prevalence of patients with respiratory symptoms through active case finding and diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis among prisoners and related predictors in a jail in the city of Carapicuíba, Brazil Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2010;13:641-50. [ Links ]

17. Stoller N. Space, place and movement as aspects of health care in three women's prisons. Social Science and Medicine 2003;56: 2263-75. [ Links ]

18. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Handbook on the Management of High-Risk Prisoners. 2016. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Shenuka Singh

Associate Professor, Discipline of Dentistry | Health Sciences | College of Health Sciences

Chair: Humanities and Soc Sc Res Ethics Com.

E-mail: singhshen@ukzn.ac.za