Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Dental Journal

versión On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versión impresa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.73 no.4 Johannesburg may. 2018

CLINICAL COMMUNICATION

Osteogenesis Imperfecta type III:A report on the unusual phenotypic features of six individuals of Cape mixed ancestry heritage

Chetty MI, V; Roberts TII, VI; Stephen LXGIII, VII; Beighton P.IV, VIII

IBSc, BChD, MChD, PhD; Faculty of Dentistry, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, Cape Town, South Africa

IIBChD, MChD; Faculty of Dentistry, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, Cape Town, South Africa

IIIBChD, PhD; Faculty of Dentistry, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, Cape Town, South Africa

IMD, PhD, FRCP; Division of Human Genetics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

VBSc, BChD, MChD, PhD; University of the Western Cape/ University of Cape Town Combined Dental Genetics Clinic, Red Cross Children's Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa

VITBChD, MChD; University of the Western Cape/ University of Cape Town Combined Dental Genetics Clinic, Red Cross Children's Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa

VIIBChD, PhD, University of the Western Cape/ University of Cape Town Combined Dental Genetics Clinic, Red Cross Children's Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa

VIIIMD, PhD, FRCP University of the Western Cape/ University of Cape Town Combined Dental Genetics Clinic, Red Cross Children's Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Osteogenesis imperfecta type III (OMIM 259420) is a severe autosomal recessive disorder in which frequent fractures and progressive limb and spinal deformity result in profound physical disability. The condition is heterogeneous and dentinogenesis imperfecta (Dl) is an important syndromic component of some types of 01 III. Other maxillofacial and dental manifestations also have significant implications in terms of management.

The prevalence of Osteogenesis imperfecta type III (OI III) as a category of the inherited connective tissue disorders in South Africa is of paramount importance. Although autosomal recessive (AR) Ol is rare worldwide, it has emerged that the frequency of OI III is relatively high amongst the indigenous Black African population of South Africa. A review of the literature revealed a paucity of information regarding the dental and craniofacial manifestations of the disorder in this ethnic group. For these reasons, the central theme of this report is the identification, documentation and analysis of these features in five individuals with Ol III in SA.

In an overall study, a total of 64 Black African affected persons were assessed. In a nested study five persons of Cape Mixed Ancestry (CMA) and three Indian individuals were investigated.1

The five CMA patients had the phenotypic features of classical Ol III, specifically severe fracturing, stunted stature, white sclerae and moderate to severe Dl. Their general health was reasonably good and longevity was a major factor. One person, the prototypic Ol III patient described in SA, was 61 years of age. Each of these individuals had massive mandibular prognathism with dental and skeletal Class III malocclusions.

In South Africa, a developing country, the allocation of resources in terms of specialized dental facilities is limited. Socio-economic barriers also exist, restricting patient access to dental care.

The previously neglected dental and craniofacial abnormalities documented in this study emphasizes the importance of a raised level of awareness in terms of dental management and the possible challenges that may be encountered.

Key words: Craniofacial, Dental, Osteogenesis imperfecta

INTRODUCTION

Osteogenesis imperfecta (Ol) is a heritable bone fragility disorder characterized by decreased bone quality and quantity and variable bone deformity.

Osteogenesis imperfecta type III (Ol III) (OMIM 259420) is a severe autosomal recessive (AR) disorder in which frequent fractures, and progressive limb and spinal deformity result in profound physical disability. The condition is clinically and genetically heterogeneous, and maxillofacial and dental manifestations have significant implications in terms of management.

The historical evolution of knowledge concerning Osteogenesis Imperfecta (Ol) has been chronicled in successive editions of Victor McKusick's magisterial book 'Heritable Disorders of Connective Tissue'.1 In the mid nineteenth century, Lobstein documented the adult form of Ol while Vrolik described the lethal infantile type. At the beginning of the 20th century, Looser of Heidelberg introduced the terms 'OI tarda' and 'OI congenita'.1 These designations have remained in use in clinical medicine.

With the onset of clinical genetics in the 1960's, the autosomal dominant (AD) mode of inheritance of Ol-tarda was well established. In Ol-conganlta, the consistent normality of the parents and the occasional recurrence In siblings was suggestive of autosomal recessive (AR) inheritance.2 By the late 1980's, however, discoveries In collagen biochemistry and later In molecular biology conclusively Indicated that Ol-congenlta resulted from new dominant mutations.3,4,5

The prevalence of Osteogenesis imperfecta type III (Ol III) as a category of the inherited connective tissue disorders In South Africa is of paramount importance. Although the autosomal recessive (AR) Ol is rare worldwide, it has emerged that the frequency of 01 III Is relatively high in the Indigenous Black African population of South Africa.6

In South Africa and Zimbabwe 01 III was found to be fairly common In the indigenous Black African population.8 The affected individuals originated from the Sotho, Pedl, Swazl, Zulu and Tswana linguistic groups among others and a ratio of Ol I to 01 III at 1 to 6 was estimated in this population group.3 It was suggested that the reason for this high prevalence is that the unaffected heterozygote may have a biological advantage In the African environment and that the mutation for Ol III in Africa occurred more than 2000 years ago in West or Central Africa prior to migration to present day Southern Africa.7

Two doctoral studies which emanated from a collaboration between UWC Faculty of Dentistry and UCT Department of Human Genetics were carried out In the field of thin bone disorders, in particular Osteogenesis Imperfecta.

The aim of one PhD project undertaken in the late 1990's was to determine whether Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Dl) Is a diagnostic discriminant for Ol and to ascertain the prevalence and severity of Dl in various families with Ol type I (ΟΙ I).3,8 In order to fulfil this objective, more than 400 patients with Ol I were assessed.

In 2016, in another PhD, 72 individuals with a confirmed diagnosis of Ol III were assessed. The focus of the study was to investigate and document the oro-dental features in affected Black African persons in SA. Five individuals of Cape Mixed Ancestry (CMA) heritage presented with the phenotypic characteristics of Ol III. Three Indian persons with an unusual form of autosomal recessive Ol were also investigated. A total of 72 individuals with the Ol III phenotype were assessed.

The number of affected individuals that were Included In these studies made up the largest series In the world.

The CMA group of affected Individuals were phenotypically defined as having Ol III with short stature and multiple fractures. They differed from the majority of the Black African persons with Ol III by virtue of their longevity and presence of Dl. Their molecular status also differed as they were negative for the determinant mutation In FKBP10 described in exon 5 which Is frequently identified in Black African persons.8 For these reasons, the phenotypic, craniofacial and dental manifestations of this unique group of Individuals are presented and discussed in this report.

AGE, GENERAL PHYSICAL CONDITION, DENTINOGENESIS IMPERFECTA AND MOLECULAR FINDINGS

Individuals are represented by alphabetical-numerical designations pertaining to the investigation centre and the chronological order In which they were assessed.

The affected persons examined at the University of the Western Cape (UWC) dental school were members of the Cape Mixed Ancestry population group and were designated CPT2, CPT3, CPT4, CPT5 and CPT6 (Figure 1 - Figure 10). Their clinical data are presented in Table 1.

Each person had limited oral opening and all their teeth were discoloured consistent with moderate to severe Dl. Their scleras were white in every instance and there was no hearing loss. None of the individuals had received bisphosphonate therapy.

Comment

It is of interest that all five affected persons were female. CPT 4 and CPT 5 were twins. The disorder occurred sporadically in the other affected individuals except in the family of CPT 2. The phenotypic features and radiographic manifestations of each patient are described In the brief case reports which follow.

CASE REPORTS

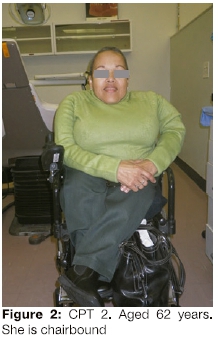

CPT 2

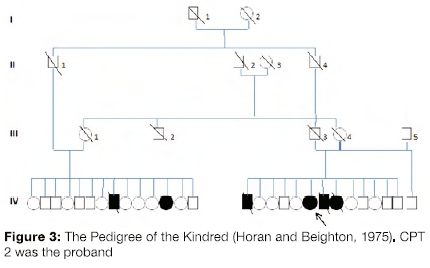

Forty-two years ago, affected individuals in five interrelated families were reported.15,20 These persons were the prototypic Ol III affected persons described in South Africa. CPT 2, then 22 years of age and now aged 60 years (Figure 1 and Figure 2), was a member of one of these families. In one family, two of 14 siblings had Ol while in the other, four of thirteen individuals were affected with Ol. The original pedigree of the kindred is shown in Figure 3.

These families shared the common CMA genetic heritage but there was specific information that they also had Black African, Scottish and Indian heritage. The fathers of the affected siblings were an uncle (11-1) and nephew (III-3) who married sisters (111-1 and III-4). Despite the reported absence of consanguinity, it can be assumed from pedigree data that the parents shared a considerable percentage of their genes. The parents and their progenitors were unaffected.

The Proband, CPT 2, had sustained several fractures by the age of two years and in early childhood had been institutionalized at a home for disabled children in Cape Town until 14 years of age. In 1975, at the age of 22 years, she was documented as being 105cm in height with severe scoliosis and pronounced bowing of the femora and humeri. At that time, she walked with the aid of long leg callipers and crutches (Figure 1) and she had minimal bluing of the sclerae.

In 2014, person CPT 2 was re-examined by one of the authors and her clinical manifestations were documented. She was chairbound; 96 cm in height (Figure 2), her teeth were discoloured and showed mild features of Dl (Figure 4). She gave a dental history of severely discoloured primary teeth and considers that her secondary teeth are less severely discoloured.

A cone beam CT was requested by a maxillofacial surgeon after CPT 2 was referred for an evaluation of pain in the region of her right TMJ which was exacerbated when chewing. She also experienced intermittent tingling and numbness in her right arm. Frequent sinus infections and nasal obstruction were also troublesome. Her hearing and mental faculties were normal.

CPT 3

CPT 3 was the only affected person in her family. Her non-consanguineous parents and a male sibling were normal. In 2014, at 21 years of age, she was 90cm in height, and was chairbound with severe scoliosis and pronounced bowing of her femora and tibia (Figure 5). She had slight difficulty hearing but her sclerae were normal.

She gave a history of severe DI in her primary dentition and this was also evident in her secondary dentition (Figure 5). Deposits of interdental calculus were present and during oral prophylaxis, moderate gingival bleeding was observed.

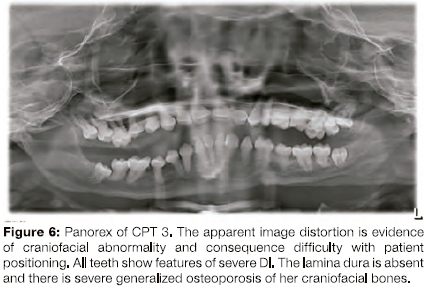

As a young woman, she was understandably concerned about the appearance of her teeth and was referred to the Department of Restorative Dentistry at UWC. A previously obtained panorex radiograph was made available to the authors (Figure 6) and a CBCT was requested by the attending prosthodontist.

The presence of Dl in all of her teeth was confirmed on a panorex radiograph (Figure 6). Optimal radiographic images of any kind were impossible to obtain due to the difficulty of positioning her due to the short stature and chairbound situation.

CPT 4 and CPT 5

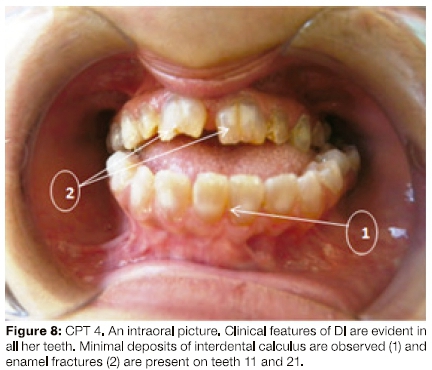

CPT 4 and CPT 5 are twin sisters (Figure 7) and are the only affected persons in their family. Their parents were unaffected and non-consanguineous. There was no history of the disorder in any of their parents' progenitors. The sisters were 93cm in height and both had marked kyphoscoliosis.

They gave a history of severely discoloured primary teeth which fractured easily. At 28 years of age, they had prominent mandibular prognathism, an anterior open bite, severe Dl and interdental calculus (Figure 8).

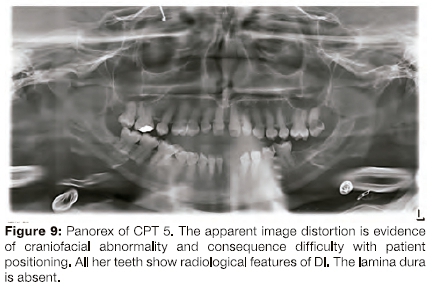

A panorex radiograph obtained in 2011 of CPT 5 showed features of severe Dl (Figure 9).

A CBCT image of both individuals was requested by a specialist prosthodontist and orthodontist, but as with the previous patients, optimal images were impossible to obtain due to difficulty with positioning.

CPT 6

At 13 years of age, CPT 6 is chairbound (Figure 10). She Is the only affected person in her family. Her non-consanguineous parents are normal and there is no history of the Ol in any progenitors. She has a younger unaffected female sibling. Her parents stated that she had a dental history of severe discolouration of her primary teeth with marked attrition and early loss. Her secondary teeth were all moderately discoloured, translucent and multiple carious lesions were observed. Mandibular prognathism was aJso present.

Due to non-cooperation from CPT 6, it was impossible to obtain dental radiographs.

DISCUSSION

The four adult affected individuals of CMA heritage, namely CPT 2, CPT 3, CPT 4 and CPT 5 ranged in age from 21 years to 63 years and had severe physical deformities. They achieved an average height of 95cm and each of them had experienced 50 or more fractures. Although none of these individuals had received bisphosphonate therapy, longevity was a major feature. CPT β at age 13 years had already experienced 20 fractures and was chairbound.

A dental history of severely discoloured primary teeth with attrition and early exfoliation was reported by each of these persons. The colour of the crowns of their secondary teeth varied from yellow to brown and they were opalescent. There was chipping, fracture and focal loss of the enamel. Radiographic images confirmed the presence of bulbous crowns and almost complete obliteration of the pulp chambers. The roots of the teeth were thin and short.

Extensive dental Intervention, management and appropriate referral was necessary due to the longevity of the individuals, the severity of the disorder and the extent of their Dl.

These observations suggest that the underlying gene defect has the same or a similar effect on bone and dentine. In this cohort of affected persons, a positive correlation between the severity of the disorder and the presence and severity of Dl was apparent. Several authors have documented the association between Ol III and the expression of severe Dl.4,10,11 These findings are, however, contrary to those observed in the Black African persons with the homozygous and compound heterozygous FKBP10 molecular genetic status and Indian persons with the unknown molecular status.

Permission to reproduce the photographs was granted.

ACRONYMS

AR: Autosomal Recessive

CMA: Cape Mixed Ancestry

Dl: Dentinogenesis imperfecta

Ol I: Osteogenesis imperfecta type I

Ol III: Osteogenesis imperfecta type III

Reference

1. Beighton, P. editor. McKusick's Heritable Disorders of Connective Tissue, 5th ad. 1993 Mosby: St. Louis, pp 281 - 95. [ Links ]

2. Horan F, Beighton P. Autosomal recessive Inheritance of Osteogenesis imperfecta. Clin Genet. 1975; 8(2): 107-12. [ Links ]

3. Beighton P, Wallis G, Viljoen D, et al. Osteogenesis Imperfecta In Southern Africa: diagnostic categorisation and blomolecular findings. Ann Ν Y Acc Sc. 1988; 543:40-6. [ Links ]

4. Lund AM, Jensen BL, Nielsen LA, et al. Dental manifestations of Osteogenesis Imperfecta and abnormalities of collagen I metabolism. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1998; 18(1): 30-7. [ Links ]

5. Slllence DO, Barlow KK, Cole W, et al. Osteogenesis Imperfecta type III. Delineation of the phenotype with reference to genetic heterogeneity. Am J Med Genet. 1986; 23(3):821-32. [ Links ]

6. Belghton P, Versfeld GA. On the paradoxically high relative prevalence of Osteogenesis Imperfecta type III in the Black population of South Africa. Clin Genet. 1985; 27(4): 398-401. [ Links ]

7. Vlljoen D, Beighton P. Osteogenesis Imperfecta type III: an ancient mutation in Africa? Am J Med Genet. 1987 ; 27:907-12. [ Links ]

8. Petersen K, Wetzel WE.. Recent findings In the classification of Osteogenesis Imperfecta by means of existing dental symptoms. ASDC J Dent Child. 1998 ; 65(5): 305-9. [ Links ]

9. Vorster A, Belghton P, Chetty M, Ganle Y, Henderson B, Honey E, Mare P, Thompson D, Fleggen K, Vlljoen D, Ramesar R. Osteogenesis Imperfecta Type III In South Africa; Mutations In FKBP10 are causative. SAMJ.107{5): http://dx.doi.oip/10.7196/samj.2017.v107i5.9461 [ Links ]

10. Schwartz S, Tslpouras P. Oral Findings In Osteogenesis Imperfecta. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984 ; 57(2): 161-7. [ Links ]

11. O'Connell AC, Warini JC. Evaluation of oral problems in Osteogenesis Imperfecta population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999; 87(2): 189-196. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Associate Professor Μ Chetty

Email: drmchetty@mweb.co.za

Phone:021 9373112