Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.73 no.3 Johannesburg Abr. 2018

RESEARCH

Reasons why South African dentists chose a career in Dentistry, and later opted to enter an academic environment

VC Mostert

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: This study aimed to investigate the reasons why South African dentists chose to study Dentistry, later opting for an academic career.

Methods: A cross sectional survey using an anonymous 12-point questionnaire that was sent out to a cohort of dentists and specialists holding positions at the four South African universities which offer a dental degree. Descriptive statistics were calculated using STATA Release 14.

RESULTS: Of 160 questionnaires distributed, 66 were completed. Popular reasons dentists cited for choosing this career were job security, a desire to help people, the degree is recognised, love working with their hands, and regular but flexible working hours. The main reasons the respondents chose an academic career were a need for intellectual stimulation, desiring a broad spectrum of work, having a love for teaching, wanting to influence or shape the profession, to pursue postgraduate studies and to do research. More than half (55%) of respondents would not choose Dentistry as a career again.

CONCLUSION: This study revealed that the career motivations of this cohort of SA dentists was far less related to the socioeconomic aspects of Dentistry than it was to their desire for more mental stimulation, in contrast to many findings elsewhere.

Key words: Career motivations, academic career, problems faced.

INTRODUCTION

Evidence gathered in 2001 showed that there was a shortage of lecturing staff in Dental Faculties throughout the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States of America (USA).1-3 It has been reported that the situation is related to the fact that dentists in private practice in the USA earn much higher salaries than do the academic dentists. Together with increasing the salaries, John et al. suggest that the shortage could be addressed by changing the academic culture to one respected and seen as noble, and the implementation of a mentor program.1 In South Africa (SA), however, there are generally many applications for positions in academic Dentistry and the posts are usually easily filled.4 This raises the question as to why more South African dentists opt for a career in academia than their overseas colleagues? By doing so they undertake a commitment to invest in and uphold the standards of, that dental school to contribute to the career development of all learners and to ensure that the profession continues to flourish in the future. The rewards for the lecturer include witnessing students being transformed from shy and insecure first years to confident, competent graduates during their years of study. An academic career may also allow a dentist the privilege of furthering his/her own education while at the same time benefitting from paid employment. Time and opportunities are also available to pursue research topics of interest.5

The literature is replete with articles concerning the stresses that dentists in private practice experience, due to constant interaction with patients in pain and anguish, staffing and financial problems, medical aid non-payments, overheads, intrusive noise, awkward working position etc. An interview study showed, in addition, that the increasing demands of dental patients contributed largely to stress and depression in dentists.6,7 However, dental academia has its own challenges, in particular that of the pressures of long waiting lists,8 which accumulate due to the economic status of many of the patients which precludes their seeking treatment in the private sector.

In addition to the service and teaching commitments, academic dentists are also expected to be involved in research.6 The philosophy "publish or perish" is paramount at all universities because of the financial benefits accrued by the institution as well as how research productivity impacts on international standing. Promotion is often dependent on the number of publications an applicant has in peer reviewed journals.9 It has been documented that the increased focus on research outputs has generated a burden upon academic dentists, requiring successful publication performance in order to gain more funds for the university as well as a higher ranking.6,7 Unfortunately meeting these demands is often at the expense of teaching.6 Sadly, there is not commensurate recognition given to outstanding teaching as there is to exceptional research, which could lead to ambitious clinicians reducing their undergraduate teaching commitments and devotion in order to focus more on their research outputs.9 The results from a study by Haden et al.10 in 2008 on work satisfaction among dental faculty members, showed that they found teaching students enjoyable. There were however, matters of concern, despite the positivity reported. Most significant were time constraints and a heavy workload that led to burn-out. The authors reported that faculty staff members felt overwhelmed as they had not anticipated the intensity of expectations in teaching, clinical, administrative and research duties.10

These considerations offer an explanation as to why dental academia were in a desperate position with regard to a shortage of lecturing staff in UK dental schools at the turn of the century.2 In the USA a similar crisis was found in dental education to the extent that at one stage 300 positions were vacant at forty five US dental schools.3 In a later study it was reported that 417 USA faculty posts were unfilled nationally.1

In SA, however, the opposite situation seems to exist: there is a demand for academic positions and recruiting lecturers poses little or no challenge to the dental schools.4 The literature suggests that the public health care system, socioeconomic status, medical aids, litigation and sustainability are linked to the relatively low rate of commitment of dentists to private practice. This is summarized below:

1. The overwhelming majority of South Africans rely heavily upon the public health sector to meet their health service needs.8,11 Socioeconomic status and prohibitively expensive medical scheme memberships are the main determinants forcing the majority of South Africans to use public health services instead of private health services. There are also times when individuals who have medical aid scheme still make use of public health services in addition to the private sector.11 The main reason for this is that they are assured that they will pay contracted-in rates at government hospitals. Many patients also feel that they will obtain a more honest opinion about treatment required as the procedures performed have no impact on the dentist's personal income.

2. Claiming from medical aid schemes poses an array of challenges encountered by dentists. These include the substantial reduction in medical aid scheme pay-outs towards Dentistry over the past 28 years, lack of funds to complete the ideal treatment procedures, time and costs incurred in telephoning and writing motivation letters to medical aids etc.12

3. Pepper and Slabbert in 2011 stated that SA has been spared the increase in litigation being experienced globally for medical and dental malpractice. There has, however, recently been a sharp spike in SA medical and dental malpractice lawsuits as patients develop an awareness of their rights in a society where resources in the health system are exhausted or otherwise limited.13

4. Many private practices are not sustainable due to The Occupation Specific Dispensation (OSD) policy which amended the vast discrepancy that previously existed between the incomes of private and public health care practitioners. This policy was implemented in 2007 by the South African government in an attempt to retain skilled health workers in the public sector. The purpose of the OSD was to provide health occupations with unique salary packages based on workers' expertise, competencies and performances.14

The above-mentioned socio-economic factors are bound to have a distinct influence on the career decisions South Africans dentists make. In addition to the rapid expansion in dental technology and the increasing dental awareness to which patients are exposed through social media, the economy has greatly affected the dental market. Financial constraints as well as skyrocketing medical and dental costs have influenced the provision of routine as well as high- tech Dentistry for many patients in both private dental practices and academic hospitals. There have been no studies that have examined the motives behind why more South African dentists apply for academic positions than do their overseas counterparts, nor to determine their satisfaction levels once having made his career choice.

The aim of this study was to identify the reasons why more dentists and dental specialists in SA were choosing a career in academia. The study also aimed to report their initial reason for selecting Dentistry as a career and whether they were satisfied with their choice.

METHODS

A descriptive and statistically analytical study was conducted amongst full time dentists and specialists employed by the four dental training schools in SA. The sample included registrars in full - time training positions. The survey consisted of 12 closed-ended questions based on previous literature, and aimed to establish factors which had led dentists to electing a career in dental academia. The questionnaire was based on a modified version of the Du Toit Questionnaire for Health Workers and Students on motives for studying Dentistry.15 Consent was given by the principal author of the Du Toit Questionnaire for Health Workers and Students. Written permission was obtained from the Deans or Heads of the four University Dental Schools for the study to be conducted. Permission was also granted by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria (212/2017). Thereafter a covering letter and consent form explaining the purpose of the study together with the questionnaires, were hand- distributed to all academic staff at each of the four schools. To ensure anonymity, two separate ballot boxes (sealed containers) were placed in a designated area at each University into which participants deposited either their consent forms or completed questionnaires. No names appeared on any of the questionnaires.

The questions were related to the demographics of respondents (dentists or specialists), their initial motives for choosing Dentistry as a career, whether they would choose Dentistry as a career path again, the reasons why they chose to enter academia, the determination as to whether they had earned more in private practice than in academia, and the identification of common problems faced by respondents in the academic environment. The demographic questions included gender, age, highest qualifications, years of employment at current institution and previous dental employment of each participant. Three of the questions, namely the initial reasons for choosing Dentistry as a career, the reason for choosing academia and the problems faced in academia, incorporated a four-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. These three questions comprised various motives in terms of personal statements with which participants could agree or disagree. The last response was named "other" for personal statements. The question as to whether they would choose Dentistry again required an explanation Why. The survey also included a question on how the gross salary in academia compared with what had been earned in private practice and whether the dentist would feel comfortable clinically to go back into private practice.

The data was analyzed using the software package, STATA Release 14. Age was the only continuous observation in this study and was summarized using descriptive statistics; mean and standard deviation. All the other responses were discrete in nature (ordinal/ nominal) and reported as frequencies, percentages, 95% confidence intervals and cross - tables.

RESULTS

Of the 160 questionnaires distributed, 66 completed questionnaires were returned (a response rate of 41.25%). It was not the desired response, but the surveys were distributed during a recess period when several dentists had taken annual leave.

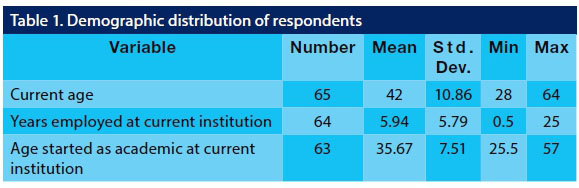

There was no significant difference in gender; 35 male and 30 female with one person not disclosing gender. Additional results of this study pertaining to demographics are displayed in Table 1 below and in Figures 1 and 2. The mean age was 41, the youngest lecturer being 28 and the oldest 64 years of age. Three quarters (75%) of the respondents had started their academic careers before the age of 40.

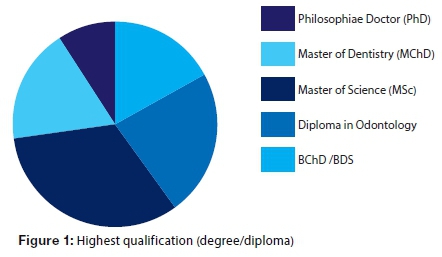

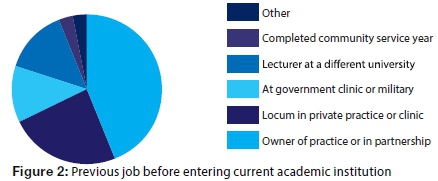

Over half of the respondents had completed a Master's degree while 17% of respondents had not completed any postgraduate studies (Figure 1). A large proportion (68%) of respondents came from private practice, whether as owner, in partnership or as a locum. The remainder of the respondents came from other government institutions such as clinics, military or another university post (Figure 2). The ranking of the most popular (strongly agreed or agreed) reasons dentists initially chose to study Dentistry is described in Table 3. The top reasons were: job security (94%), wanting to help people (86%), wanting a recognized profession (86%), love for working with hands (84%) and wanting regular (82%) working hours.

More than half (55%) of the dentists surveyed would not choose Dentistry as a career again, given a second chance to choose a career path.

The reasons respondents chose an academic career were arranged in order of prevalence. The sequence was: a need for intellectual stimulation (90%), desiring a broad spectrum (service, teaching and research) of work (90%), having a love for teaching (89%), wanting to influence or shape the profession (86%), to pursue postgraduate studies (81%) and to undertake research (71%) (Figure 4).

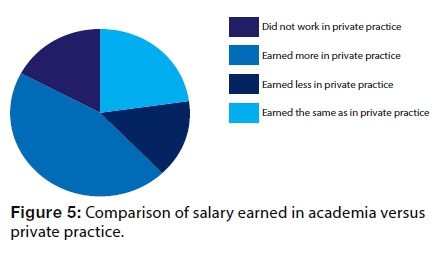

The majority (45%) of respondents reported that they had earned more in private practice while 23% had earned the same and only 17% had earned less in private practice. The rest of the respondents had not been in private practice (Figure 5).

More than half (52%) of the respondents did not feel comfortable clinically to go back into private practice.

The overwhelming majority (95%) of respondents reported facing problems in academia. The top three problems were pressure to publish in the limited time allocated for research (77%), inflexible working hours which do not make provision for running important errands (71%) and administration and meetings tend to be a frustration (70%). Figure 6 describes the reasons for stress in academia.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study that not only analyses the motivation academics had in choosing to study Dentistry and why they chose an academic career but also displays the satisfaction of dentists in their choice of a career path.

The results of this study revealed that the majority (75%) of respondents entered academia before the age of 40. This is a good age for doing postgraduate studies and teaching students, supported by some clinical experience. The highest qualification obtained more or less balances with the percentage of respondents wanting to enter the academic career to do post graduate studies. A number of respondents are still new in their academic posts which provides an explanation why 17% of respondents have not obtained any postgraduate qualification. Most academic positions for dentists that are advertised in SA have a post graduate diploma as the minimal requirement.

The result of the study reveals that it is of absolute importance to carefully choose your career path. It is among the most important decisions to be made as an adult and the wrong choice can have negative consequences both financially and psychologically.16 Job security and a degree leading to a recognised job (the most popular reasons our respondents chose to study Dentistry) can be achieved in many other career paths. Students applying for a university degree may do so because they want job security, but this does not mean they will enjoy being a Dentist. In the same way, having a love to work with your hands could be satisfied through becoming a mechanic or wanting to help people through studying psychology. An interview or written essay which is currently not part of the dental students' selection determinants in SA could be of great value in ensuring students make the right career choice.15 Apprenticeship used to be a requirement for all professions a few hundred years ago, so students knew what to expect from the profession. Currently one of the expectations of dental applicants at Manchester University is to have observed a dentist at work before applying.17 "Work experience" would help Dentistry applicants establish whether they are making a career decision that suits their skills, personalities and interests. However, factors motivating dentists to make a career choice would differ from country to country.18 The motivations the respondents in this study had when choosing a career could have arisen from the economic situation and joblessness in SA. The fact that more than half of the dentists would not choose Dentistry as a career again questions their motivation for studying the discipline and indeed could be a reflection of the incorrect choice in the first instance. This could be the reason for their entering the academic environment. The dentists in academia are often perceived by private practitioners as the ones that could not "make it" in private practice. The results of this study however showed that the majority of dentists entering the academic field desired intellectual challenge or a broad spectrum of work which included service, teaching and research. Respondents also differed in that some dentists would feel rewarded by a satisfied patient while others would enjoy the rewards of frequent publications.

Salaries in academia which are substantially lower than the salaries in private practice is cited as the leading cause for a shortage of academic dentists in many countries.19 The value of additive benefits of being an academic such as a pension fund, paid leave, working at the cutting edge of technology and self-development programs available at the University are underestimated. Although a large proportion of the respondents of this study had a higher income in private practice, it is clear that money was not a motivation for becoming an academic. South African universities employ numerous sessional or part time workers which may contribute to the abundance of applicants for full-time positions. Many of the applicants for lecturing positions are employed on a sessional basis at the dental school which exposes them to the "other side of Dentistry". These sessional dentists come to realize how their constructive feedback benefits these future dentists and will experience the satisfaction that comes with seeing a student grow and development under their guidance.

Academic dentists in SA are usually placed in a specific department where they teach and carry out service in a particular discipline of Dentistry such as extractions or orthodontics. This may lead to a lack of confidence or reduction in speed and quality in other disciplines of Dentistry and could be a reason why just over half of the academic dentists did not feel comfortable going back into private practice. The personal experience of the author identified a need for dentists in academia to continue part-time work in private practice or hospital environment in order to retain confidence as well as to keep abreast of new developments in Dentistry.

It is very clear from the results of this study that academia can be challenging; only five percent of academic dentists felt they did not face problems or challenges in academia. Time is a major concern in academia which is a hurdle that can be overcome. A solution may be to allow lecturers more flexibility and to assess the outcome of their work rather than the time spent at work. Sixty-two percent of respondents felt the need for an overview of academic writing to be included for undergraduate students. Implementing this suggestion in the curriculum could lead to academic staff being more productive or faster with research outputs.

CONCLUSION

The perspectives of South African academic dentists were significantly different from those in the US and the UK. A desire to teach and be intellectually stimulated dominated the decision of the respondents in this study to enter academia, above the financial aspects. Methods of selection of dental students appear to require some modification to ensure that the right choice of career is made. Making work experience prior to application into dental school a requisite could eliminate misconceptions aspirant dental students may have of the profession. Academia may have its challenges but could be a rewarding job for the dentist who is less fond of the practical side of Dentistry.

Acknowledgement:

I would like to acknowledge Professor PH Bekker (Biostatistician, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria) for his assistance with the statistical analysis of the results.

ACRONYMS:

OSD : Occupation Specific Dispensation

References

5. John V, Papageorge M, Jahangiri L, Wheater M, Cappelli D, Frazer R, Sohn W. Recruitment, development, and retention of dental faculty in a changing environment. J Dent Educ. 2011; 75 (1): 82-9. [ Links ]

6. Patel N, Petersen HJ. Would you choose an academic career? Views of current dental clinical academic trainees. Br Dent J. 2015; 218 (5): 297-301. [ Links ]

7. Schenkein HA, Best AM. Factors considered by new faculty in their decision to choose careers in academic Dentistry. J Dent Educ. 2001; 65 (9): 832-40. [ Links ]

8. Swart, Ina (2017) HR Manager, University of Pretoria Oral Health Centre, Gauteng Health. Conversation with author in May 2017. Personal communication. [ Links ]

9. Kay EJ, O'Brien KD. Academic Dentistry-Where is everybody? Br Dent J. 2006; 200 (2): 73-4. [ Links ]

10. Rutter H, Herzberg J, Paice E. Stress in doctors and dentists who teach. Med Educ. 2002; 36 (6): 543-9. [ Links ]

11. Humphris GM, Cooper CL. New stressors for GDPs in the past ten years: a qualitative study. Br Dent J. 1998; 185(8): 404-6. [ Links ]

12. Mostert VC, Postma TC. The capacity of the Oral Health Centre, University of Pretoria, to complete root canal treatments. SADJ. 2016; 71 (8): 356-60. [ Links ]

13. Rawat S, Meena S. Publish or perish: Where are we heading?. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences: the Official Journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. 2014 Feb;19(2):87. [ Links ]

14. Haden NK, Hendricson W, Ranney RR, Vargas A, Cardenas L, Rose W, Ross R, Funk E. The quality of dental faculty work-life: report on the 2007 dental school faculty work environment survey. J Dent Educ2008; 72(5): 514-31. [ Links ]

15. Alaba OA, McIntyre D. What do we know about health service utilisation in South Africa? Dev South Afr. 2012; 29(5): 704-24. [ Links ]

16. Snyman L, van der Berg-Cloete SE, White JG. The perceptions of South African dentists on strategic management to ensure a viable dental practice. SADJ. 2016; 71(1): 12-8. [ Links ]

17. Pepper MS, Slabbert MN. Is South Africa on the verge of a medical malpractice litigation storm? SAJBL 2011; 4 (1): 29-35. [ Links ]

18. Gavaza P, Rascati KL, Oladapo AO, Khoza S. The state of health economic research in South Africa. Pharmaco-economics. 2012; 30(10): 925-40. [ Links ]

19. Du Toit J, Jain S, Montalli V, Govender U. Dental students' motivations for their career choice: an international investigative report. J Dent Educ. 2014; 78 (4): 605-13. [ Links ]

20. Willner T, Gati I, Guan Y. Career decision-making profiles and career decision-making difficulties: A cross-cultural comparison among US, Israeli, and Chinese samples. J Vocat Behav. 2015 Jun 30; 88:143-53. [ Links ]

21. University of Manchester, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health. Requirements for Dentistry (first-year entry) application and selection (2017 entry). At: https://www.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/dentistry/study/undergraduate/dentistry-bds-foundation/?pg=4 Accessed: August 23, 2017. [ Links ]

22. Kobale M, Klaic M, Bavrka G, Vodanovic M. Motivation and career perceptions of dental students at the School of Dental Medicine, University of Zagreb, Croatia. ActaStomatol Croat. 2016; 50(3): 207-14. [ Links ]

23. Shugars DA, DiMatteo MR, Hays RD, Cretin S, Johnson JD. Professional satisfaction among California general dentists. Journal of Dental Education. 1990 Nov 1;54(11):661-9. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr VC Mostert:

P.O Box 1266, Pretoria, 0001.

Tel: 012 319 2459, Cell: +2784 654 2322

Email: vanessa.mostert@up.ac.za