Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.72 no.5 Johannesburg Jun. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2017/v72no5a5

CASE REPORT

Oral medicine case book 74: Marijuana-induced Oral Leukoplakia

Dada TemilolaI; Haly HolmesII; Sune Mulder Van StadenIII; Amir AfroghehIV

IBChD. Division of Oral Medicine and Periodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, University of the Western Cape

IIBChD, MSc, MChD. Division of Oral Medicine and Periodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, University of the Western Cape

IIIBChD, MChD. Division of Oral Medicine and Periodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, University of the Western Cape

IVBChD, MSc, MChD, IFCAP. Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Faculty of Dentistry, University of the Western Cape, National Health Laboratory Service, Tygerberg Hospital

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old male presented at the Oral Medicine Clinic of the University of the Western Cape, Oral Health Centre, Tygerberg Campus, for the evaluation of a persistent white patch on his right edentulous mandibular ridge. He had been referred from the Prosthodontics Clinic where he was seen for complete denture rehabilitation. The patient had no significant medical history and informed us that he had been smoking marijuana five times a day for more than twenty years and consumed alcohol occassionally. He had never worn a dental prosthesis and did not use tobacco in any form.

Extra-oral examination revealed bilateral submandibular lymphadenopathy and asymptomatic clicking of both temporomandibular joints during jaw opening. Intraoral examination showed completely edentulous upper and lower arches with a healing extraction socket in the posterior third quadrant. An asymptomatic, white homogenous plaque measuring 3x5mm, which could not be wiped off, was present on the crest of the right mandibular ridge (Figure 1).

Due to the small size of the lesion, an excisional biopsy was performed under local anaesthesia. Following the surgical procedure, the patient was prescribed 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate oral rinse and 500mg Paracetamol four times daily.

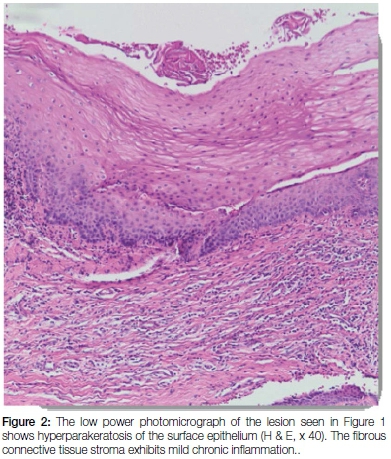

Histological examination of the excised white plaque disclosed a fragment of squamous mucosa with acanthosis and hyperkeratosis (Figure 2). The sub-epithelial connective tissue was densely collagenized and showed a mild chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. There was no evidence of dysplasia or malignancy in the histological sections examined. The Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) stain was negative for fungal elements.

Evaluation of the biopsy site after two weeks showed complete resolution of the lesion. Based on the clinical and microscopic features, a diagnosis of non-dysplastic marijuana-induced oral leukoplakia was established. The patient was advised to stop smoking marijuana since there is a risk of possible malignant change. He was instructed to return to the clinic in six months for his periodic follow up visit.

DISCUSSION

Oral white lesions reflect many different diseases and pathological changes. Leukoplakia was first defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 19781 as a white patch or plaque which cannot otherwise be characterized clinically or pathologically as any other disease. A revised definition was proposed in 2007 by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer and Pre-cancer Working Group, in which leukoplakia was defined as "a white plaque of questionable risk, having excluded other known diseases or disorders, that carry no increased risk for malignant transformation."2

Worldwide, the estimated prevalence of oral leukoplakia is 1.7% to 2.7% for all age groups.3 Between 16% and 62% of oral squamous carcinomas are reported to arise from an area of oral leukoplakia,4 emphasizing the need for routine oral screening programs and regular monitoring of high risk individuals.

Globally, leukoplakias are reportedly diagnosed after the fourth decade of life and are six times more common among smokers than non-smokers.2 A clinical diagnosis of oral leukoplakia is made when a predominantly white lesion cannot be clearly diagnosed as any other disease or disorder of the oral mucosa. A biopsy is mandatory, since the differential diagnosis of leukoplakia is broad and may include oral lichen planus, pseudomembranous candidiasis, chemical injury, frictional keratosis, oral lichen planus, oral epithelial dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma.2

The most common aetiologic factor for leukoplakia is tobacco smoking, cessation of which may lead to regression or total disappearance of oral leukoplakia.5 A definite link between marijuana use and oral leukoplakia has not been established. Most studies of oral leukoplakia have focused on the role of tobacco as an aetiologic factor, since tobacco smoking is a more socially acceptable behaviour. In addition, the legal use of marijuana is restricted to certain countries.

More recently, marijuana use has been legalized in many states in America and some European countries. An American study found that marijuana use among adults in the United States has doubled in the last decade.6 In South Africa, the use of drugs such as marijuana, "tik" (metamphetamine) and cocaine is twice the global average and the highest in Africa.7

Marijuana is derived from the macerated flowers of Cannabis satava and contains the toxic compound A9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a cannabinoid, which constitutes 1-6% m/v of the total weight of the plant flowers.8 In addition, more than 60 other cannabinoids have been identified in cannabis. When cannabis is smoked as marijuana, the resultant heat leads to aromatization of the cannabinoids and to carcinogenic substances such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, benzo[a]-pyrene, phenols, phytosterols, acids and terpenes, which are detectable in marijuana smoke.9 Marijuana thus carries the same carcinogens found in cigarette smoke and these carcinogens are known to cause DNA damage, which could potentially lead to malignant transformation.

In general, leukoplakias with dysplasia pose a higher risk for malignant transformation, compared with non-dysplastic leukoplakias.5,10 Several molecular biomarkers have been proposed, but currently, no single biomarker can accurately predict the potential for malignant transformation.11

Currently, a range of non-invasive adjunctive diagnostic methodologies are available to screen oral potentially malignant disorders (PMDs), such as oral leukoplakias. These include vital staining techniques (using toluidine blue/tolonium chloride/ lugol's iodine),12 light based detection systems13 and exfoliative cytology.14

Toluidine blue (TB) is a basic thiazine metachromatic dye, which stains tissues rich in nucleic acids because of its high affinity for acidic tissue components. Both dysplastic and neoplastic cells contain more nucleic acids than normal cells. TB-stained tissue may appear dark or pale royal blue and has been used for many years as an aid for the screening and post-surgical management of PMDs and oral cancer.15,16 It has been reported that TB staining could assist in early detection of oral cancer compared with conventional visual inspection alone.17 A systematic review revealed that TB has a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 70% and can be a valuable diagnostic tool in screening of large group of patients.18 A high percentage of false positive results have been associated with TB due to its ability to stain cells in benign hyperplastic and inflammatory lesions, which also contain large quantities of nucleic acids.19

A number of light-based detection systems such as Vizilite, Vizilite plus, Microlux DL, narrow mission tissue fluoroscence and the Velscope, have been developed. The principle of these light-based detection systems is based on the fact that mucosal tissues undergoing inflammatory, abnormal metabolic or structural changes have different absorbance and reflectance profiles when exposed to various forms of light sources, enabling the differentiation of oral mucosal abnormalities.20 ViziLite shows high sensitivity (77%) and low specificity (28%)20 in detecting oral PMDs and oral cancer.21 Some studies found that ViziLite could not differentiate between keratotic or inflammatory oral PMDs and oral cancer.22,23 The Vizilite Plus combines the features of the Vizilite and TB and can further delineate ViziLite-positive lesions, thus improving its specificity as a diagnostic tool.24

Exfoliative cytology is a quick and simple procedure based on a relatively atraumatic semi-invasive technique, allowing for the collection of a rich concentrate of cells over a wider area than selective tissue biopsy and is ideal for use in large leukoplakic lesions. Recent cytologic techniques, such as liquid based cytology (LBC), have further improved the quality of oral cytologic smears.25 With LBC; the residual liquid based material can be used for immunocytochemistry and molecular testing.

Currently, none of the adjunctive diagnostic tests could be recommended as a replacement for scalpel biopsy and histopathological assessment.18 However, the use of adjunctive tests (e.g. the use of Velscope to guide biopsies, and exfoliative cytology in large leukoplakic lesions), can further improve the overall accuracy of the histological assessment.

CONCLUSION

The current case report describes a unique case of marijuana-induced oral leukoplakia. With the increased use of marijuana in South Africa, a rise in marijuana -induced oral leukoplakic lesions may be expected. Dentists and oral hygienists should be aware of the possibility of marijuana use when confronted with oral leukoplakic lesions and their potentially malignant nature. The use of adjunctive screening tests may further improve the overall accuracy of histological examination.

ACRONYMS

LBC: liquid based cytology

PMDs: potentially malignant disorders

TB: Toluidine blue

WHO: World Health Organization

References

1.Kramer IR, Lucas RB, Pindborg JJ. Definition of leukoplakia and related lesions: an aid to studies on oral precancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1978;46:518-39. [ Links ]

2.Warnakulasuriya S, Johnson NW, Van der Waal I. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med.2007;36:575-80. [ Links ]

3.Petti S. Pooled estimate of world leukoplakia prevalence: a systematic review. Oral Oncol 2003;39:770-80. [ Links ]

4.Brouns ER, Baart JA, Bloemena E, Karagozoglu H, Van der Waal I. The relevance of uniform reporting in oral leukoplakia: definition, certainty factor and staging based on experience with 275 patients. Oral Diseases 2013;20 (93):e19-24. [ Links ]

5.Van der Waal I. Oral potentially malignant disorders: is malignant transformation predictable and preventable? Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Buccal 2014;19(4):e386-390. [ Links ]

6.Hasin D, Saha S, Kerridge TD et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72(12):1235-42. [ Links ]

7.Burns L. World Drug Report 2013 By United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime New York: United Nations, 2013ISBN: 978/92/1/056168/6, 151 pp. Grey literature. Drug and Alcohol Review 2014;33(2):216-216. [ Links ]

8.Firth NA. Marijuana use and oral cancer: a review. Oral Oncology 1997;33(6):398-401. [ Links ]

9.Nahas G, Latour C. The human toxicity of marijuana. Medical Journal of Australia 1992;, 156(7):495-7. [ Links ]

10.Reibel J. Prognosis of oral pre-malignant lesions: significance of clinical, histopathological and molecular biological characteristics. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003;14:47-62. [ Links ]

11.Johnson NW, Ranasinghe AW, Warnakulasuriya S. Potentially malignant lesions and conditions of the mouth and oropharynx; natural history - cellular and molecular markers of risk. Eur J Cancer Prev 1993;2:31-51. [ Links ]

12.Chole RH, Patil RN, Basak A, Palandurkar K, Bhowate R. Estimation of serum malondialdehyde in oral cancer and precancer and its association with healthy individuals, gender, alcohol, and tobacco abuse. Journal of cancer research and therapeutics 2010;6(4):487 - 91. [ Links ]

13.Gómez I, Warnakulasuriya S, Varela-Centelles PI, López-Jornet P, Suárez-Cunqueiro M, Diz-Dios, P. Is early diagnosis of oral cancer a feasible objective? Who is to blame for diagnostic delay? Oral Diseases 2010;16(4):333-42. [ Links ]

14.Kujan O, Desai M, Sargent A, Bailey A, Turner A, Sloan P. Potential applications of oral brush cytology with liquid-based technology: results from a cohort of normal oral mucosa. Oral Oncology 2006;42(8):810-18. [ Links ]

15.Epstein JB, Guneri P. The adjunctive role of toluidine blue in detection of oral premalignant and malignant lesions. Curr Opin Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg 2009;17:79-87. [ Links ]

16.Awan KH, Yang YH, Morgan PR, Warnakulasuriya S. Utility of toluidine blue as a diagnostic adjunct in the detection of potentially malignant disorders of the oral cavity-a clinical and histological assessment. Oral Diseases 2012;18:728-33. [ Links ]

17.Su WW, Yen AM, Chiu SY, Chen TH. A community-based RCT for oral cancer screening with toluidine blue. J Dent Res. 2010;89:933-7. [ Links ]

18.Macey R, Walsh T, Brocklehurst P, et al. Diagnostic tests for oral cancer and potentially malignant disorders in patients presenting with clinically evident lesions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015; Issue 5. Art. No.: CD010276. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD010276. pub2. [ Links ]

19.Driemel O, Kunkel M, Hullmann M, et al. Diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma and its precursor lesions. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2007;5:1095-100. [ Links ]

20.Awan KH, Morgan PR, Warnakulasuriya, S. Evaluation of an autofluorescence based imaging system (VELscope™) in the detection of oral potentially malignant disorders and benign keratoses. Oral Oncol 2011;47:274-7. [ Links ]

21.Patton LL, Epstein JB, Kerr AR. Adjunctive techniques for oral cancer examination and lesion diagnosis: a systematic review of the literature. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2008;139:896-905. [ Links ]

22.Farah CS, McCullough MJ. A pilot case control study on the efficacy of acetic acid wash and chemiluminescent illumination (ViziLite) in the visualisation of oral mucosal white lesions. Oral Oncol 2007;43:820-4. [ Links ]

23.Ram S, Siar CH. Chemiluminescence as a diagnostic aid in the detection of oral cancer and potentially malignant epithelial lesions. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg 2005;34:521-7. [ Links ]

24.Rashid A, Warnakulasuriya S. The use of light-based (optical) detection systems as adjuncts in the detection of oral cancer and oral potentially malignant disorders: a systematic review. J. Oral Pathol. Med 2015;44:307-28. [ Links ]

25.Afrogheh A, Wright CA, Sellars SL, et al. An evaluation of the Shandon Papspin liquid-based oral test using a novel cytologic scoring system. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology 2012;113(6):799-807. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Haly Holmes

Division of Oral Medicine and Periodontics, Faculty of Dentistry

University of the Western Cape

Francie Van Zyl Drive, Tygerberg Campus

Tel: 27 21 9373102

E-mail hholmes@uwc.ac.za