Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562

Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.71 n.10 Johannesburg Nov. 2016

RESEARCH

Bacteriology and management of orofacial infections in a Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery Clinic, South Africa

EM MolomoI; DP MotlobaII; MM BouckaertIII; MM TlholoeIV

IBDS, MDent (MFOS) FCMFOS (SA). Specialist / Lecturer Department of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, School of Oral Health Sciences, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University

IIBDS, MPH (Epid), MDent (Comm.Dent), MBL. Head, Department of Community Dentistry. School of Oral Health Sciences, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University

IIIMDent, FFD, FCMFOS, Professor, Department of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, School of Oral Health Sciences, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University

IVBCur (Medunsa), BDS (Medunsa), BChD (UL), FCMFOS (SA), Specialist / Lecturer Department of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, School of Oral Health Sciences, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The widespread use of antibiotics in clinical medicine has contributed to a significant decline in the morbidity and mortality attributable to orofacial infection. However, there are indications of global variations in the microbiology, sensitivity to antibiotics and clinical outcomes, which have not been studied locally.

AIM OF THE STUDY: To investigate the bacteriology and antimicrobial sensitivity of microorganisms causing orofacial infections amongst patients attending a local Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery Clinic, in order to inform an appropriate antibiotic therapy regimen.

METHODOLOGY: Study design and setting: A retrospective record-based survey conducted at the Medunsa Oral Health Centre, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, South Africa.

DATA COLLECTION: Demographic details, clinical information and laboratory data (identified microorganisms and antibiotic sensitivity), were acquired from files dating between March 2011 and June 2015.

RESULTS: In total 122 pathogens had been successfully cultured from 127 patient specimens. The profile of microorganisms was predominately aerobic, with Streptococcus viridans, Coagulase negative staphylococcus and Staphylococcus aureus comprising the majority. All responded favourably to first line antibiotics. Penicillin, clindamycin and gentamycin were the most effective antimicrobials.

CONCLUSION: Penicillin remains the drug of choice in treating orofacial infections. The current study discourages the indiscriminate use of metronidazole.

Keywords: orofacial infections, bacteriology, sensitivity testing

INTRODUCTION

Orofacial infections are common conditions that originate in the oral cavity and the face with the propensity to spread to adjacent tissues. While largely odontogenic in origin, the infections could arise from other structures of the face and oral cavity.1,2 The spectrum includes periapical infections, which if untreated may spread to fascial spaces and in severe cases may result in Ludwig's angina and widespread necrotizing fasciitis.3Streptococcus spp and Staphylococcus spp have been largely implicated as causative agents.4

Antibiotic therapy has resulted in significant reductions in the morbidity and mortality associated with orofacial infections.5 Despite this success, an increasing resistance to antimicrobial agents is reported, because of the indiscriminate use of antibiotics and the evolution of micro-organisms.6,7

Prescribing successful antimicrobial therapy is a function of clinical experience and the availability of scientific evidence. Hence pragmatic and rational approaches to the selection of antibiotics should be encouraged when dealing with infections in order to limit development of anti-microbial resistance.8 The current regimen used at the Department of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, Medunsa Oral Health Centre, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University is based on international recommendations and has not been derived from local data to support clinical practice.

This study was therefore carried out to characterize the micro-organisms involved in orofacial infections and to provide evidence to inform the development of antimicrobial therapy regimens to treat pathogenic micro-organisms in the Department of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery.

METHODOLOGY

Study design and setting:

This study was completed by means of a descriptive, retrospective survey of patient records. Ethical approval was given by Medunsa Research and Ethics Committee Clearance certificate number MREC/D/301/2013.

Participants

Records of patients treated at Medunsa Oral Health Centre (MOHC) for orofacial infections from March 2011 to June 2014 were reviewed. Inclusion criteria required that the records icontained the surgeon's clinical data as well as information from the National Health Laboratory Services (NHLS) database which recorded the classification of micro-organisms and details of the antimicrobial sensitivity tests. From the clinical records information was acquired including age and gender of the patient, site of infection, history of antibiotic use and history of treatment for the orofacial infection. All case records meeting the inclusion criteria were used for this study.

Laboratory procedures

Bacterial culture and microscopic identification were performed by calibrated microbiologists in the National Health Laboratory Services (NHLS), Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University. All the specimens submitted to this centre were sourced and handled according to the NHLS (SOP's) standard operating procedures and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. Aspiration sites were cleaned with alcohol. Sufficient amounts of pathological matter were aspirated from these sites and stored in the appropriate storage medium. The specimens were delivered within an hour of collection to the NHLS for analysis.

Antimicrobial sensitivity testing was also conducted by the NHLS to determine the susceptibility of Streptococcus viridans, Coagulase negative Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus aureus to commonly prescribed first line antibiotics such as, penicillin, erythromycin, gentamycin, metronidazole, and second line drugs such as cloxacillin. First line therapy or primary treatment refers to treatment regimens that are generally accepted by the medical establishment for initial treatment of a given condition. These regimes are standard of care and are the first choice of treatment. Second-line antibiotics are drugs used when the first line regimen does not work adequately.

Data collection

Two calibrated researchers independently abstracted data from the clinical records and NHLS printouts. Data were captured electronically in a specially designed spreadsheet prior to statistical data analysis.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using a Statistical Package for Social Sciences Inc. (IBM SPSS ver. 23.0, for Windows, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Initial analyses included inter and intra -observer reliability testing using Cohen's Kappa test. All variables were subjected to appropriate descriptive and analytical statistical analyses. Pearson's Chi-Square tests and odds ratios were calculated to test the associations between categorical variables. All tests were carried out at α =0.05.

RESULTS

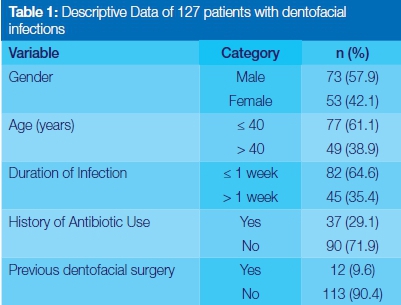

Demographics and clinical characteristics of participants (Table 1)

The study comprised 127 files in which were recorded details of patients who had suffered orofacial infections. Males constituted 73 (57.9%) of the sample. The mean age and standard deviation (SD) of the sample were 38.62 (SD: 16.23) years and age ranged from 3 to 78 years. On admission, 82 (64.8%) patients had presented with acute infections (lasting a week or less), and 90 (71.9%) had had no previous history of antibiotic use related to orofacial infection (Table 1).

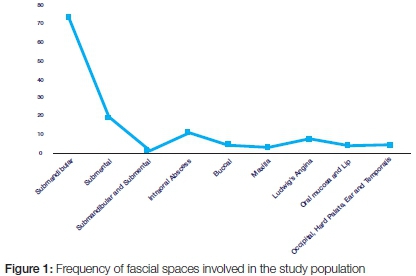

Distribution of spaces involved in orofacial infections

Orofacial infections originated mainly from the submandibular area, 57.5% (73), submental infections 15.0% (19), and intra-oral abscesses, 8.7% (11). Ludwig's angina occurred in 7 cases (5.5%). The hard palate, lip, occipitum, ear, and temporalis and other tissues were also infected in a minority of cases. (Figure 1)

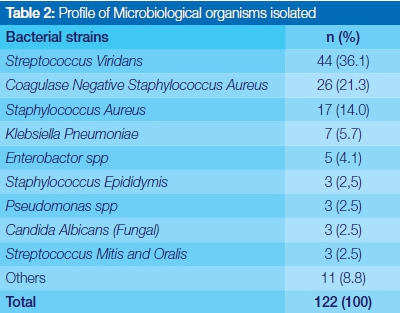

Profile of microbial isolates

A total of 122 strains of microorganisms were isolated from the specimens. Of the isolates, four species of bacteria constituted 77.1% (94) of all microorganism cultured. Prominent aerobic organisms isolated included Streptococcus viridans, 36.1% (44); Coagulase negative staphylococcus aureus 23% (26); Staphylococcus aureus 14.0% (17); and Klebsiella pneumoniae 5.7% (7). Strains of candida albicans were also positively identified (Table 2).

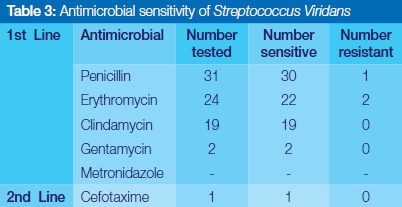

Antimicrobial sensitivity test

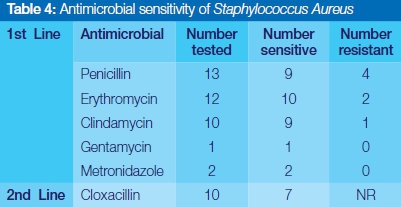

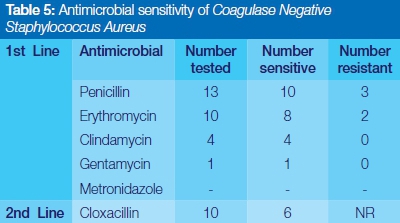

Streptococcus viridans was completely sensitive to Clindamycin, Gentamycin and Cefotaxime, and highly responsive to the use of commonly prescribed penicillin and erythromycin (Table 3). Staphylococcus aureus showed relatively high susceptibility to the first line of antibiotics selected in this study. No resistance was reported for Gentamycin, Metronidazole and the second line drug, cloxacillin (Table 4). Coagulase negative staphylococcus aureus showed complete sensitivity to Clindamycin, and Gentamycin, but significant episodes of resistance to penicillin and erythromycin were encountered (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

This study used clinical records in the investigation of the prevalence of microorganisms associated with orofacial infections in patients presenting at a local clinic and assessed the recorded sensitivity of common organisms to antibiotic therapies. In this study, more males than females presented with orofacial infections, a finding similar to previous studies.8-10 The mean age of our participants was 38.62 years, slightly lower than the average of 40 years reported in some studies.8,9,11

The relevant literature records that the facial spaces most commonly affected by orofacial infection include the submandibular, lateral pharyngeal, buccal, and submental spaces, in descending order of involvement for both multi- space and single space infections.3,8,9 In terms of single space involvement most studies concur that the submandibular space is the most commonly involved site, followed by buccal and canine spaces.2,10 Whilst the current study also identified the submandibular space as the most frequent site of involvement, the results differ in terms of the occurrence of infection in all other spaces. The predominance of submandibular space infections is attributed to the presence of carious mandibular molars.

Bacteria isolated in the current study consisted of aerobic organisms. Low counts of anaerobic organisms could be attributed to the acute nature of infections managed in this clinic, and a history of no previous antibiotic use in 71.9% of the patients. Mixed infections mature over time, resulting in an overgrowth of anaerobes in the later stages of the infection.12 These findings are not consistent with most of the published literature, which predominately indicates anaerobic colonization in orofacial infection.11,13,14

Streptococcus viridans, Coagulase negative staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumonia remain the most frequently isolated pathogenic microorganisms in orofacial infections in the current study. Many researchers have demonstrated similar findings in orofacial infections of odontogenic origin.7,10,15,16 The high levels of staphylococcus could reflect actual colonization or the introduction of staphylococcus from the skin during treatment. A positive culture of Candida albicans in our study corroborates reported findings that this oral commensal may be a significant opportunistic micro-organism in the oral cavity.8,10

Based on our findings, penicillin remains the treatment of choice for orofacial infections in the local context. Erythromycin, clindamycin and gentamycin have been shown to be effective antimicrobials against Streptococcus viridans, Coagulase negative Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Klebsiella pneumonia. Cloxacillin, is the most effective second line of antibiotics for these bacteria. Similar results have been reported in the literature.7,8,17-19 Our study, supported by convincing literature,6,20 casts questions on the common use of erythromycin, when safer non- β- lactams are available. Similarly, both the current study results and other published works10,20 do not advocate the use of metronidazole as the drug of first choice in most orofacial infections.

These findings demonstrate that in the majority of patients, routine bacteriological sampling provides no added therapeutic value. Most orofacial infections respond favourably to first line antimicrobials and can be successfully managed without additional laboratory investigations. However, in patients with acute resistance, further investigations should be undertaken to isolate the micro-organisms and to determine the most appropriate antimicrobial therapy for management of orofacial infections.

Limitations of the study

A retrospective, record based study design and the small sample size could have a negative effect on the validity and generalization of the results. Despite these limitations, this study provides a sound contribution to the existing body of knowledge and supports current clinical practice.

CONCLUSION

Streptococcus viridans is the most frequently isolated pathogen from orofacial infections and responds to first line antibiotics especially penicillin. Powerful second line drugs remain an alternative in resistant infections.

Recommendations

We recommend stringent bacteriological sampling in patients with complicated orofacial infections, following thorough evaluation of clinical and other related factors. Penicillin should be the first line of treatment in orofacial infections. Prospective, large, multicentre studies should be undertaken to validate these findings.

References

1. Bratton T, Jackson D, Nkungula-Howlett T, Williams C, Bennett C. Management of complex multi-space odontogenic infections. The Journal of the Tennessee Dental Association. 2001;82(3):39-47. [ Links ]

2. Boscolo-Rizzo P, Da Mosto MC. Submandibular space infection: a potentially lethal infection. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009;13(3):327-33. [ Links ]

3. Britt JC, Josephson GD, Gross CW. Ludwig's angina in the pediatric population: report of a case and review of the literature. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2000;52(1):79-87. [ Links ]

4. Kuriyama T, Karasawa T, Nakagawa K, Saiki Y, Yamamoto E, Nakamura S. Bacteriologic features and antimicrobial susceptibility in isolates from orofacial odontogenic infections. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 2000;90(5):600-8. [ Links ]

5. Gill Y, Scully C. Orofacial odontogenic infections: review of microbiology and current treatment. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology. 1990;70(2):155-8. [ Links ]

6. Baker KA, Fotos PG. The management of odontogenic infections. A rationale for appropriate chemotherapy. Dental Clinics of North America. 1994;38(4):689. [ Links ]

7. Walia IS, Borle RM, Mehendiratta D, Yadav AO. Microbiology and antibiotic sensitivity of head and neck space infections of odontogenic origin. Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery. 2014;13(1):16-21. [ Links ]

8. Chunduri NS, Madasu K, Goteki VR, Karpe T, Reddy H. Evaluation of bacterial spectrum of orofacial infections and their antibiotic susceptibility. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery. 2012;2(1):46. [ Links ]

9. Byers J, Lowe T, Goodall C. Acute cervico-facial infection in Scotland 2010: patterns of presentation, patient demographics and recording of systemic involvement. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2012;50(7):626-30. [ Links ]

10. Kityamuwesi R, Muwaz L, Kasangaki A, Kajumbula H, Rwenyonyi CM. Characteristics of pyogenic odontogenic infection in patients attending Mulago Hospital, Uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiology. 2015;15(1):1. [ Links ]

11. Kannangara DW, Thadepalli H, McQuirter JL. Bacteriology and treatment of dental infections. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology. 1980;50(2):103-9. [ Links ]

12. Winkelhof A, Velden U, Graaff J. Microbial succession in recolonizing deep periodontal pockets after a single course of supra and subgingival debridement. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 1988;15(2):116-22. [ Links ]

13. Flynn TR, Shanti RM, Levi MH, Adamo AK, Kraut RA, Trieger N. Severe odontogenic infections, part 1: prospective report. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2006;64(7):1093-1103. [ Links ]

14. Storoe W, Haug RH, Lillich TT. The changing face of odontogenic infections. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery. 2001;59(7):739-48. [ Links ]

15. Shweta S. Dental abscess: A microbiological review. Dental Research Journal. 2013;10(5):585. [ Links ]

16. Uluibau I, Jaunay T, Goss A. Severe odontogenic infections. Australian Dental Journal. 2005;50(s2):S74-S81. [ Links ]

17. Krishnan V, Johnson JV, Helfrick JF. Management of maxillofacial infections: a review of 50 cases. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1993;51(8):868-73. [ Links ]

18. Orzechowska-Wylęgała B, Wylęgała A, Buliński M, Niedzielska I. Antibiotic therapies in maxillofacial surgery in the context of prophylaxis. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015. [ Links ]

19. Rega AJ, Aziz SR, Ziccardi VB. Microbiology and antibiotic sensitivities of head and neck space infections of odontogenic origin. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2006;64(9):1377-80. [ Links ]

20. Fowell C, Igbokwe B, MacBean A. The clinical relevance of microbiology specimens in orofacial abscesses of dental origin. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2012;94(7):490-2. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Edward M Molomo

E-mail: molomoem@webmail.co.za