Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.71 no.10 Johannesburg Nov. 2016

RESEARCH

Piloting the Community Service Attitudes Scale in a South African context with matching qualitative data

MG PhalwaneI; TC PostmaII; OA Ayo-YusufIII

IBDent Ther, BDS, PGDip (Comm Dent), PGDip HPE. Lecturer, Department of Community Dentistry, School of Oral Health Sciences, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, South Africa

IIMChD (Comm Dent), DHSM, PhD. Senior Lecturer, Department of Dental Management Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IIIBDS, MSc, MPH, DHSM, PhD. Director School of Oral Heal Sciences, Director/ Acting Executive Dean, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: There is a need to measure the social accountability of dental students following service learning (SL) exposure.

OBJECTIVES: To pilot the Community Service Attitudes Scale (CSAS) and to test its reliability in a South African context while matching CSAS findings with students' perceptions of their SL experience.

METHODS: Final year dental students at Sefako Makgatho University anonymously completed a modified version of the CSAS and submitted written reflections before and after SL exposure. Students also participated in two focus group discussions after exposure. Before and after CSAS data were statistically compared using t-tests. Qualitative data from the focus groups and reflective essays were matched against the findings of the CSAS.

RESULTS: Students (n=41, 76% CSAS response rate) generally displayed positive attitudes towards communities in need, both before and after exposure (no statistical difference). The CSAS internal consistency was excellent (α = 0.96). Qualitative findings suggested a need for stakeholders' involvement in the procurement of SL resources and in meeting community needs. There was tension between SL and quota-driven dental training.

CONCLUSION: The CSAS showed good reliability and appears a useful tool to measure social accountability in South Africa. The qualitative findings need further investigation.

INTRODUCTION

Service learning has become an integral part of dental education.1 Service learning (SL) is included in undergraduate curricula to develop the social awareness and responsibility of students by exposing them to communities in need.2 It has been proposed that the alignment of academic objectives with a SL experience, followed by structured reflection, brings about critical, deep and long-lasting learning that embraces community dynamics.3 It also fosters social responsibility which will help influence and shape public policy in future. Thus, dental graduates are expected to become advocates for needy communities.3

The effect of SL on the attitudes of dental students has been measured on several occasions.4-6 The majority of studies, mostly conducted in developed countries, suggested positive effects on students' attitudes towards SL4,6 while at least one reported no changes in students' attitudes following exposure to SL.5

Notably, the effects of SL have been investigated only a few times in an African context.6,7 Evidence from the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa suggests that there was an increase in social responsibility and personal growth following participation in community projects.6 Although such studies provide valuable insights in terms of the effects of SL in local contexts, most of their measurement tools lack conceptual rigour and comparability.

The Community Service Attitudes Scale (CSAS)8 is an alternative questionnaire that could provide standardisation and conceptual rigour. The CSAS is a validated questionnaire based on Schwartz's Model of Helping Behaviour9 that measures changes in social awareness and responsibility in four phases.8,9 Phase One is the "activation" step whereby participants in SL become aware of the needs in society and the need for action, in the context of their own abilities and feelings of connectedness to the problem. In the Second Phase, the "obligation" step, the participants feel empathetic and sense a moral obligation to react to this need. During Phase Three, the "defense" step, participants assess their stance towards reacting to the need, partly based on the perceived importance of the problem and partly based on personal impact (personal cost and personal benefit). Finally in Phase Four, participants express intentions to respond with action (helping behaviour) to address the need.4,8,9

The CSAS has not been used extensively in dental education but appears to be a suitable tool for comparative studies in different settings and to measure change over time.4 The reliability (internal consistency) and construct validity of the CSAS have been tested in a developed world setting and appear to be of good quality.4,8 The CSAS has however not been used or tested in a developing world context. It is highly conceivable that dental students who grew up in an African setting are most likely to possess high levels of awareness of poverty and inequality, which may have influenced their value systems and helping behaviour. A need therefore exists to test and pilot the CSAS in an African setting before it is used on a large scale to evaluate the effects of SL.

The primary objective of the study was thus to apply the CSAS in a South African context and to test the internal consistency of the questionnaire. The secondary objective was to match the CSAS findings with student perceptions of their SL experience.

METHODS

Ethical approval was obtained from Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University (SMU); previously called the Medical University of Southern Africa (MEDUNSA).

Data collection and statistical analysis - Quantitative component

Final year dental students (2014) at the Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, South Africa, reported their demographic information (age, race, gender and level of education) and their preferred sector of employment after qualification.

The students anonymously completed a modified version of the CSAS4,8 before and after their experience in exposure to community service. The questions of the CSAS were organised according to the phases and domains of Schwartz's Model of Helping Behaviour9 (Figure 1). Since Questions 8a-e were negatively framed, the values obtained from this domain were reversed for the purpose of the statistical analysis.

Reliability (internal consistency) analyses were conducted by means of the Cronbach Alpha statistic10 on domain, phase and questionnaire levels. A Cronbach Alpha coefficient of 0.7 was considered to be an indicator of acceptable internal consistency (data quality).

A t-test was used to analyse the responses to pre- and post-exposure questionnaires on question and domain levels. Because of the multiple tests conducted during the analyses, a p-value less than 0.001 was considered to be statistically significant.

Data collection - Qualitative component

Two focus group discussions11 were conducted during the eight-week SL rotations. The primary researcher (PMG) conducted the focus group discussions directly after students returned from their community engagement experience in their randomly allocated groups. No attempt was made to influence the demographic composition of the groups. Each focus group discussion comprised ten participants. The set of questions displayed in Figure 2 was used for the two interview sessions. A tape recorder was used to capture all discussions; and information was stored on audio tapes. Transcription of the information was done to paper, and the data later transferred into Microsoft Word.

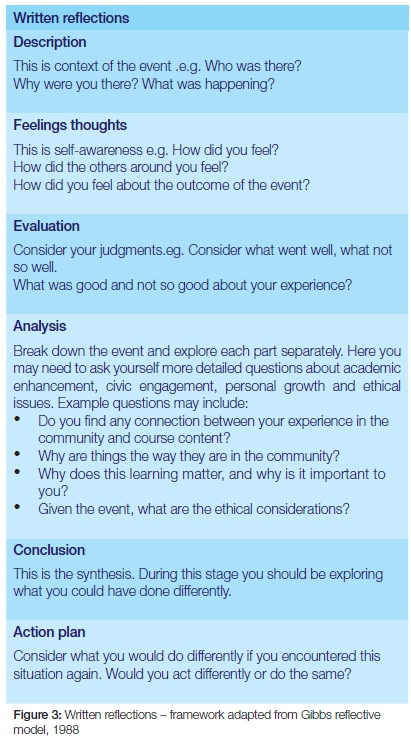

Pre and post-exposure reflective essays were also used as an additional source of qualitative data. After the focus group discussions, the students were requested to write a reflective essay at home. The Department of Community Dentistry, School of Oral Health Sciences (SOHS) had adapted a reflective template (Figure 3) from Gibbs (1988),12 which was used as a guide for writing the essays.

Quotations extracted from the transcribed focus group discussions and reflective essays were combined and subsequently organized according to the domains (Figure 1) of the CSAS that served as the qualitative theme. The original coding and data extraction was done by the primary researcher (PMG) and controlled by the second author of this article (TCP).

RESULTS

Forty one (76%) of the 54 final year students completed both the pre- and post-exposure questionnaires. Most (90.2%) respondents were Black African students and 45% were male. The majority (53.7%) were 26-30 years of age, while 26.8% were 21-25 years old. The remainder of students were older. At least 60.9% possessed a tertiary qualification. More than half of the students (53.7%) had expressed a desire to work in the public sector after qualification. Three quarters (75.6%) of the students had not previously been exposed to community projects.

CSAS results

Both pre- and post-exposure responses were positive towards community service (Table 1) except for those regarding "personal cost", which were somewhat neutral. No statistical differences (t-test) could be found between before and after scores on a question or domain level although the data showed a small decline for all the indicators.

The Cronbach Alpha analyses (Table 1) consistently rendered coefficients of more than 0.70 on a domain and phase level, with a coefficient for the entire questionnaire of 0.96.

Focus group discussion and reflective essay results

The qualitative results are displayed below by means of a selection of illustrative quotes, arranged according to phases and domains of the CSAS (Figure 1).

Activation step: Students' perceptions of community needs (Phase 1)

The following are illustrative quotes that indicate students' "awareness" of community needs:

"I am informed by my social background. That is why I can identify with most patients' social circumstances."

"Here at the school they may have an ideal patient but out there patients have limitations."

"Local people are poor in the real sense …"

"Things are the way that they are due to lack of knowledge of patients."

"… as a result they get substandard treatment, extractions and maybe restorations if they are lucky. There are no extensive services."

The following are illustrative quotes that show student awareness of the "need for action" to assist communities in need:

"Yes, we do have the knowledge but there needs to be action for things to happen and change to be effected."

"SL needs stakeholder action."

"There are definitely possibilities out there; let us move out of this confinement of the dental walls … The government must assist. Proposals can be drafted for expansion of this programme. Government departments must be involved, not only theoretically."

The following are illustrative quotes indicative of students' perceptions of their "ability to make a difference" and factors that impede their making a difference.

"SL is different, we unleash our abilities of patient management and to run the clinic."

"Out there we do reach out to the impoverished communities but impeded by the old, long-broken equipment."

"… how do we start when there are no materials, and instruments are old and broken?"

"I feel that politicians fail our communities so much. We have good SL models of how to do things in communities but have no resources to undertake those activities. I wonder where this saga is going to end?"

The following quotes illustrate students' "connectedness" with communities in need:

"I am from poverty myself, so I can contribute positively in any destitute community."

"You want to stay out there in the community for SL and feel that you are contributing to improve lives."

"I want to see myself helping the patient from beginning to the end: follow-up to see everything is okay eventually. I want to be happy to have assisted the patient."

Obligation step: Students' normative appraisal of their stand towards community service (Phase 2)

The following are illustrative quotes that indicate the students' sense of "moral obligation" to react to the needs of poor communities:

"There is a lot to be done because patients come here with caries and go back with the same, but out there you make sure you do not send the patient home the same way they came."

"People are treated looking at their poor backgrounds. We must treat people first and not the background."

The following quotes illustrate the "empathy" of students with communities in need:

"Most of them do not know what else we do as dental practitioners except for tooth extraction. It hurts to see this…"

"Local people are poor in the real sense and sending them back home without treatment is like committing some murder."

"When we visit the Bagdad community they ask us if we are going to build houses for them. You can see that going there just for oral health is a drop in an ocean. Our appearance there gives them false hopes."

"When you're the outsider without understanding the person situation, I always judged how can one let a disease spread and get worse without seeking treatment. Looking at what the communities are going through I now understand the dilemma. One must think of where the next meal is coming from before anything."

Defense step: Students' reassessment of their stand towards community service (Phase 3)

The following is an illustrative quote that indicates students' sense of the "importance of community service":

"The war against community problems will not be won easily if things remain the way they are."

The following quotes show the students' perceptions of "personal cost" in the context of their participation in SL:

"BDS is quite a stressful course; strenuous with superficial information. It is a too congested programme. It feels like an initiation school more than academic."

"Presently we are chasing clinical quota so badly... we are forever faced with circumstances beyond our control. It (SL) puts pressure on students."

"Presently we do not have a choice but to swallow everything that is thrown at us. We lack time for introspection."

The following quotes show the students' perceptions of "personal benefit" in the context of their participation in SL:

"In SL you do introspection as an individual."

"There is an opportunity for growth with SL because we are more relaxed and learn at our pace, unlike at MOHC (School)."

"… at SL that is where you see growth and progress into becoming a doctor, undisturbed."; "You perfect your skills unimpeded; you engage with community members. You actually manage to get a patient to trust you."

"This where I truly found myself as opposed to the training inside the school."

"Stereotypes are cleared, time to reflect positively and learn from it, and independent decision-making. I feel confident and independent."

"It was a great opportunity for us to treat so many people in need. I see improvement in professionalism and principles of inter-professional care."

Response step: Students' intentions to help communities in future (Phase 4)

The following quotes illustrate students' "intentions to help communities in future":

"Most definitely, I will serve the impoverished communities."

"Well, I will do community service at the rural area of my choice with no coercion from the department because I like it."

"If management cooperates with me, I will do something where I am going. There is so much harvest out there."

"I am waiting for the day when we will be treating patients at their own homes; doing all the necessary dental procedures and checking on all other problems that they have, transporting them to and from the local health facility, to improve their quality of life."

"We can start with key groups like pension services, churches, and mother and child clinic. Know people and organise the clinic to address their needs. We can start inside and out; by writing a business plan and presenting it to the community leaders, apply the knowledge gained throughout the years of dental training."

DISCUSSION

This pilot is the first study to apply the CSAS in a South African context to measure change in attitude towards community service in a cohort of dental students before a larger scale application at a later stage. Qualitative data was also collected to gain a sense of student perceptions about community service in a South African context. For the first time it was shown that SL in an African context may not have had a positive effect on students' attitude towards underserved communities. In fact, a small decline was observed albeit statistically insignificant. Such a finding was only made once before in a developed world setting.5 Using the phases of the CSAS as conceptual guide, these somewhat surprising results can be explained as follows:

Activation step

The quantitative results suggests that students displayed positive attitudes during the activation step in the domains of "Awareness", "Action", "Ability" and "Connectedness".

The qualitative results supported the quantitative findings indicating that some of the students were already aware of the social problems and inequality through their life experience even before they engaged in SL. The post-exposure qualitative data shows that although the students felt that action is necessary, consistent with the multi-sectoral approach to primary health care, they sensed that other key stakeholders will have to make substantial contributions to make real differences. Public health facilities and equipment are often under-resourced in developing world contexts such as South Africa.13 The qualitative results also indicate that students are aware that their role as oral health care providers will be limited when they are not empowered with the necessary resources to deal with the problems, hence their call for key stakeholders to come to the party. Therefore, it is conceivable that community exposure would not necessarily improve student attitudes any further in this South African context unless the SL experience is making a meaningful difference to the community with support of adequate resources. Both the quantitative and qualitative findings showed that the students appeared to have a sense that they have the ability to make a difference and indeed expressed personal connectedness to community problems.

Obligation step

The above-mentioned findings in the Activation step may have influenced the normative assessment of the situation by students and their assessment of the importance of community engagement before the SL took place. The pre- and post-exposure quantitative findings suggest that the students felt morally obliged to do community service and that they displayed empathy in their behaviour. The post-exposure quantitative results did not produce many expressions of moral obligation but there was plenty of empathy towards the needs and shortcomings of the communities they visited.

Defense step

It is therefore not surprising that students regarded community service as important in the Defense step of the CSAS.

The slightly more negative assessment of "personal cost" compared with the other domains appeared to be logical given the time pressures of an undergraduate dental curriculum. The qualitative data indeed shows the pressures the students have to absorb when dealing with achieving minimum procedural quotas and having to participate in SL at the same time. It appears as if students felt that the quota-driven discipline-based teaching and learning14 takes preference despite their own assessment of a need for community service and patient-centred care. The results of the study show a clear conflict between students' normative assessment of the need for learning in the community and what is happening during their hospital-based training.14 Despite this ethical conflict, the quantitative and qualitative results suggest that the majority of students, to a large extent, realised the personal benefits of SL.

Response step

Again the above-mentioned appraisal informs the students' positive attitudes, in terms of helping behaviour, that were observed during the study.

Limitations and strengths of the study

A major limitation of this small scale study is the use of a single cohort as source of quantitative information. The purpose of the study was however to test the CSAS in a South African context before large scale deployment. The results have shown that reliable information can be obtained from the CSAS in a South African context.

The strength of the study is the matching of the quantitative results with qualitative findings to gain some sense of different quantitative observations.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study suggest that the reliability (internal consistency) of the CSAS was considered good within the South African context.

The quantitative results suggested that the effects of SL may be distinctly positively influenced by other key stakeholder involvement in the procurement of resources to enable broader service delivery to communities in need. This issue needs further exploration and clarification. Moreover, the apparent ethical tension between quota-driven clinical training and SL also needs to be further elucidated.

The promising results from the current and previous studies4 combined with the conceptual rigour9 of the instrument makes the CSAS an attractive tool for comparative studies in the field of SL to measure social accountability in an educational setting.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

ACRONYMS

CSAS: Community Service Attitudes Scale

SL: Service learning

References

1. Hood JG. Service-learning in dental education: meeting needs and challenges. J Dent Educ 2009: 73: 454-63. [ Links ]

2. Brondani MA. Teaching social responsibility through community service-learning in predoctoral dental education. J Dent Educ 2012: 76: 609-19. [ Links ]

3. Yoder KM. A framework for service-learning in dental education. J Dent Educ 2006: 70: 115-23. [ Links ]

4. Coe JM, Best AM, Warren JJ, McQuistan MR, et al. Service learning's impact on dental students' attitude towards community service. Eur J Dent Educ 2015: 19: 131-9. [ Links ]

5. Volvovsky M, Vodopyanov D, Inglehart MR. Dental students and faculty members' attitudes towards care for underserved patients and community service: do community-based dental education and voluntary service-learning matter? J Dent Educ 2014: 78: 1127-38. [ Links ]

6. Bhayat A, Vergotine G, Yengopal V, Rudolph MJ. The impact of service-learning on two groups of South African dental students. J Dent Educ 2011: 75: 1482-8. [ Links ]

7. Kroon J, Prince E, Denicker GA. Trends in treatment performed in the Phelophepa Dental Clinic: 1995-2000. SADJ 2001: 56: 462-6. [ Links ]

8. Shiarella AH, McCarthy AM, Tucker ML. Development and construct validity of scores on the community service attitudes scale. Educ Psychol Meas 2000: 60: 286-300. [ Links ]

9. Schwartz SH. Normative Influences on Altruism. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 1977: 10: 221-79 [ Links ]

10. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes: Cronbach's alpha. Br Med J 1997: 314: 572. [ Links ]

11. Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br Dent J 2008: 204: 291-5. [ Links ]

12. Gibbs G. Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Oxford: Oxford Further Education Unit, 1988. [ Links ]

13. Coovadia H, Jewkes R, Barron P, Sanders D, McIntyre D. The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges. Lancet 2009: 374: 817-34. [ Links ]

14. Eriksen HM, Bergdahl J, Bergdahl M. A patient-centred approach to teaching and learning in dental student clinical practice. Eur J Dent Educ. 2008: 12:1 70-5. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Motlalepula G Phalwane:

Department of Community Dentistry, School of Oral Health Sciences,

Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University

P O Box 955, MEDUNSA, 0204

Tel +2712 521 4862

Fax +2712 521 3832

Email: grace.phalwane@smu.ac.za