Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.71 no.10 Johannesburg Nov. 2016

RESEARCH

The efficiency of the referral system at Medunsa Oral Health Centre

SR MthethwaI; N J ChabikuliII

IBDS (Wits), MPH (Wits), PhD (University of Limpopo). Department of Oral Pathology & Oral Biology, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University

IIBOH (Medunsa), BDS (Medunsa), MDS (University of Limpopo). Department of Maxillofacial Radiology, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University

SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION: The functioning of various referral systems in health service delivery at district level have been described.

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES: To examine the effectiveness of the elective treatment referral system that operates internally at Medunsa Oral Health Centre. The proportion of emergency and non-emergency patients who consulted at the diagnostic unit and were subsequently referred for elective treatment at clinical units during February 2013 was compared with those who had actually received treatment one year later.

DESIGN: This was a retrospective, comparative cross-sectional study in which existing medical records were reviewed.

METHODS: Treatment records of emergency and non-emergency patients who consulted at the diagnostic unit and were subsequently referred to clinical units for elective treatment during February 2013 were reviewed one year later. The service register of the diagnostic unit for the month of February 2013 was also reviewed. Data related to the referral preferences of attending clinicians, demographic characteristics and dates when treatment was actually received was extracted.

RESULTS: Significantly fewer (14.6%) patients of either group were treated than were referred. The average waiting time for treatment was 81.2 days and ranged between 6 and 184.5 days.

CONCLUSIONS: The internal referral system that operates at Medunsa Oral Health Centre was shown to be inefficient.

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

A hierarchical referral system is followed in the public health sector in South Africa.1 The functioning of various referral systems in service delivery at district level have been described.1-3 Very little was found in the literature concerning referral systems and dentistry.

A recent national health care facilities audit found that dental services are lacking across the board at primary health care level in South Africa.4 High attendance rates were reported where services were available and accessible.5,6 However, the range of services offered was often limited to emergency treatment of pain and sepsis.7

A referral system operates between Medunsa Oral Health Centre, a dental school and a comprehensive care referral hospital in the outskirts of Pretoria, and dental clinics in the Tshwane health district. The effectiveness of this referral system has however not been examined.

At Medunsa Oral Health Centre new and repeat self-referred and referred patients, not on the hospital appointment system, routinely move between the diagnostic unit, a screening and referral clinic, where experienced dentists examine them and clinical units where dental students under faculty supervision provide treatment or treatment appointments are scheduled.

Emergency patients are triaged based on the severity of their illness, injury or pain and referred to emergency clinics. The attending dentist determines the appropriate treatment and referral options.

• Facial swelling, bleeding (trauma affecting the mouth), an accident involving damage to the mouth or teeth, or dental pain are referred to Minor Oral Surgery/ Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery.

• Restorative emergencies, dental pain and injuries to teeth and the pulp are referred to Care line clinic.

Multiple problems are also assessed. They are however not addressed in emergency appointment -referrals are made to elective clinics at that time. At emergency clinics, the dentist will aim to reduce or stop the pain experienced. Emergency clinics can make referrals to elective clinics. Prosthodontics emergencies are referred to the prosthodontics clinic.

Patients with less urgent problems are referred for general dental care and or for initial assessment in the relevant specialty clinics. They are placed on a waiting list for care and are informed when a booking becomes available.

General dental examinations and care is offered through oral hygiene, minor oral surgery and operative dentistry clinics. This dental service includes routine dental examinations or check-up, oral health advice, scale and polish, extractions, fillings, fissure sealants and root canal treatments.

Referrals for specialist dental services from community oral health/ medical services also pass through the diagnostic unit. Specialist dental care is often provided as part of a treatment plan in combination with other specialty clinics.

The number and configuration of general care and specialty clinics has changed over the years. In the era of the traditional six-year training program - oral hygiene; operative dentistry; orthodontics; prosthodontics; periodontics; maxillofacial and oral surgery, and a combined diagnostics and radiology clinic comprised the clinical units.8 Following the switch from the traditional six-year to a five-year program, the diagnostic clinic became independent of the radiology clinic and an integrated clinical dentistry clinic was established.9

Attempts have been made to establish referral rates for clinical units.10-12 This study examines the effectiveness of the elective treatment referral system that operates internally at Medunsa Oral Health Centre. Patient flow between the diagnostic and clinical units was investigated.

OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

1. To describe the demographic characteristics of patients who consulted at the diagnostic unit of Medunsa Oral Health Centre during the month of February, 2013

2. To determine and compare the proportions of emergency and non-emergency patients who required elective treatment with those who actually received treatment one year after consultation at the diagnostic unit

3. To determine the average elective treatment waiting time for clinical units

4. To identify patient factors associated with receiving elective treatment using multiple variable logistic regression

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a retrospective, comparative cross-sectional study in which existing medical records were reviewed.

Target population

The sampling frame consisted of treatment records of all patients, not on the hospital appointment system, who consulted at the diagnostic unit of Medunsa Oral Health Centre in February 2013.

Study sample

The ideal sample size was estimated at 323 patient records in nQuery Advisor, Release 7.0 software at the confidence interval of 95% and absolute precision of 5% assuming a referral rate of 30%. This study finally included a sample of 295 patient records.

Sampling method

A random sample of the population was selected. The lottery method of random sampling was used, i.e. patients were assigned numbers, and coupons with serial numbers ranging from 1 to 1209 were then thoroughly mixed in a bowl and 323 were drawn at random (without replacement) to provide the desired sample size.

MEASUREMENTS

Medical records

Treatment records of emergency and non-emergency patients who consulted at the diagnostic unit and were subsequently referred to clinical units for elective treatment during February 2013 were reviewed one year later. The service register of the diagnostic unit for February 2013 was also reviewed. Data related to the referral preferences of attending clinicians, demographic characteristics and dates when treatment was actually received at referral clinics was extracted.

Definition of variables

Age refers to patient age derived from date of birth recorded in the diagnostic unit service register

Gender refers to sex (general state of being male or female)

Waiting time was defined as the time between the date of consultation at the diagnostic unit and the treatment date at clinical units.

Effectiveness was assessed by determining and comparing the proportions of patients who consulted at the diagnostic unit and were deemed to require and subsequently referred for elective treatment at clinical units of Medunsa Oral Health Centre with those who actually received the treatment.

Emergency patients are those who consulted at the diagnostic unit with an issue involving teeth and supporting tissues that was fixed/treated at the emergency clinics

Emergency units are clinics where emergency oral and dental treatment is offered. They include the Minor Oral Surgery, Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, and Care line clinics.

Care line clinic is an emergency clinic where restorative emergencies, dental pain and injuries to teeth and the pulp are treated.

Non-emergency patients are those who consulted at the diagnostic unit with less urgent problems, and were placed on a waiting list for care.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University. Permission to conduct the study was granted by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Medunsa Oral Health Centre.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS / HYPOTHESIS TESTING

Data was captured, coded and cleaned in Microsoft Excel software and then transferred to Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) software for analysis.

Means, frequencies and proportions (percentages) were calculated.

Fisher's Exact Test (two-sided) was performed to test the statistical significance of the difference in the proportions of patients referred to and treated in clinical units.

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify patient factors associated with receiving elective treatment in the study population. The binary outcome of interest was received treatment (Yes/No). The determinants investigated included patient group i.e. emergency or non-emergency, age group, and gender.

RESULTS

Data extracted from a random sample of 295 treatment records was analysed.

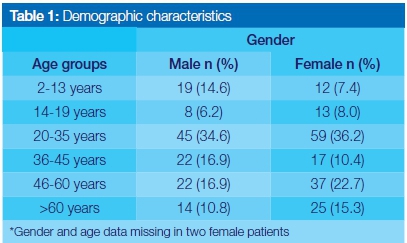

Females constituted 55.9% of patients in the study sample. Male and female patients in the 20-35 years age group comprised just over a third (35.2%) of the sample. The gender distribution in age groups older than 35 was similar (44.6% male vs 48.4% female)

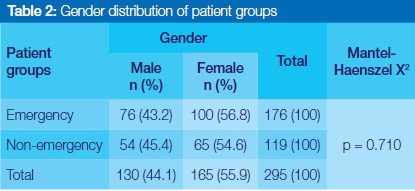

Emergency patients comprised 59.7% of study subjects. Female patients constituted 56.8% and 54.6% respectively of emergency and non-emergency patients. However, there is insufficient evidence (p>0.05) to reject the null hypothesis of no gender difference in the proportions of emergency and non-emergency patients.

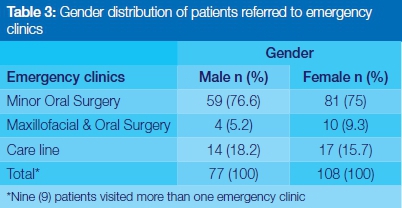

Just over three quarters of all emergency patients of both sexes visited the Minor Oral Surgery clinic. Few patients of either gender visited the Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery clinic. More males (18.2% vs 15.7%) than females visited the Care line clinic.

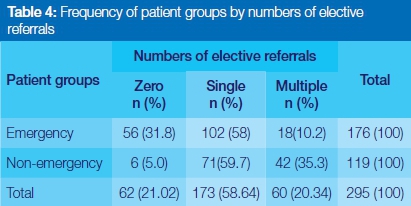

Four out of five (78.9%) study subjects received elective treatment referrals. The majority (58% vs 59.7%) of both patient groups received a single referral. Just over a third (35.3%) of non-emergency patients and a tenth (10.2%) of emergency patients were referred to multiple clinical units.

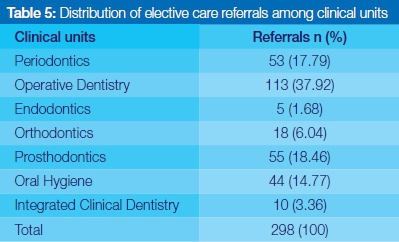

Just less than forty percent (37.92) of all referrals were made to the Operative Dentistry clinic. Similar proportions (17.79% vs 18.46%) were made to Periodontics and Prosthodontics clinics. Fewer patients were referred to Orthodontics (6.04%), Integrated Clinical Dentistry (3.36%) and Endodontics (1.68%) clinics respectively.

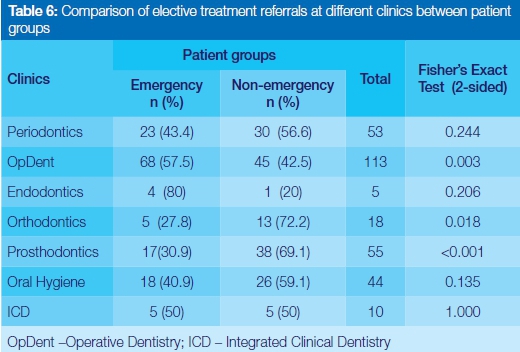

More non-emergency patients than emergency patients were referred to Periodontics, Orthodontics, Prosthodontics and Oral Hygiene whereas more emergency patients than non-emergency patients were referred to Operative Dentistry and Endodontics clinics. Equal numbers were referred to the Integrated Clinical Dentistry clinic. There was substantial evidence (p <0.05) to reject the null hypothesis of no difference in the proportions of elective care referrals between emergency and non-emergency patients in the population for Operative Dentistry, Orthodontics, and Prosthodontics clinics. However, there was insufficient evidence (p>0.05) to reject the null hypothesis for Periodontics, Endodontics, Oral Hygiene and Integrated Clinical Dentistry clinics.

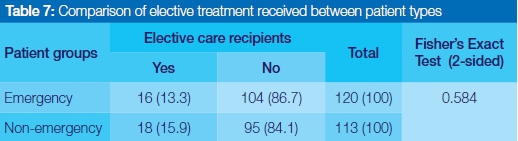

Fewer patients from either group (14.6%) were treated than were referred during the study period. Elective care was received at a rate of one in thirteen and one in sixteen for emergency and non-emergency patients respectively. There was insufficient evidence (p>0.05) to reject the null hypothesis of no difference in the proportions of patients who received elective care between emergency and non-emergency patients in the population.

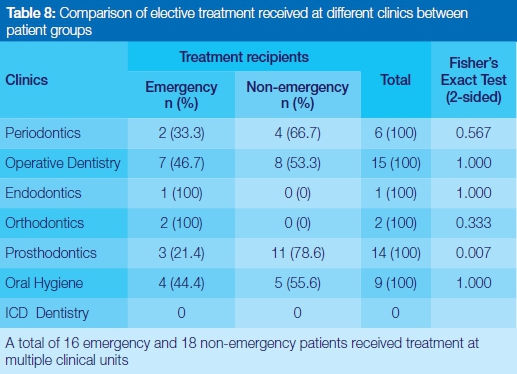

More non-emergency patients than emergency patients received treatment at Periodontics, Operative Dentistry, Prosthodontics and Oral Hygiene clinics whereas more emergency patients than non-emergency patients received treatment at Endodontics and Orthodontics clinics. There was substantial evidence (p<0.05) to reject the null hypothesis of no difference in the proportions of patients who received elective treatment between emergency and non-emergency patients in the population at Prosthodontics clinic. However, there was insufficient evidence (p>0.05) to reject the null hypothesis of no difference in the proportions of patients who received elective treatment between emergency and non-emergency patients in the population at all other clinical units.

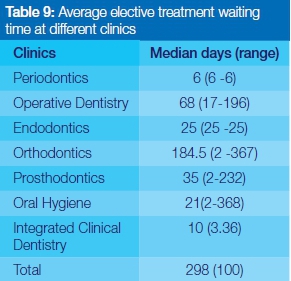

The average time lapse between consultation at the diagnostic unit and receipt of treatment in clinical units was 81.2 days with a range of just under a week (6 days) to longer than six months (184.5 days). The waiting time was relatively short for Periodontics (6 days), Oral Hygiene (21 days), Endodontics (25 days), and Prosthodontics (35 days) intermediate for Operative Dentistry (68 days) and long for Orthodontics (184.5 days).

Analysis codes: Gender (0 = male, 1 = female); Patient groups (0 = non-emergency patient, 1= emergency patient)

There was no indication of an independent relationship (p>0.05) between receiving elective treatment, gender, age group and patient groups in the study population.

DISCUSSION

This study set out to investigate the effectiveness of the referral system that operates at Medunsa Oral Health Centre. Comparable studies were not found - the functioning of referral systems at dental schools has not previously been described. A possible explanation for this might be that the inefficiency of dental school clinics is generally recognised: Treatment is provided by students according to their level of training under faculty supervision; Treatment times are longer than would be experienced in private dental practices, and lack of treatment continuity as patients are passed from year to year and from one student provider to another.13

Demographic characteristics

The results of this study indicate that more women than men (55.9% female vs. 44.1% male) visited Medunsa Oral Health Centre and that two thirds of the patients were aged 45 years and younger.

The present findings seem to be consistent with other research which found a large female preponderance at dental clinics.7,14 The age structure of the study population is consistent with that described by Lesolang and colleagues.7

Comparison of the proportions of referred and treated emergency and non-emergency patients

The current study found that more non-emergency patients than emergency patients were referred for elective treatment. However, few patients of either group received treatment than were referred in all clinical units. The most interesting finding was that an overwhelming majority (78.9%) of the study subjects were deemed to require elective treatment and received referrals, the bulk of which were to the Operative Dentistry clinic.

Considering that Medunsa Oral Health Centre is a comprehensive treatment referral hospital, the finding that more non-emergency patients than emergency patients were referred for elective treatment was not unexpected. It was however, rather disappointing that less than 20% had received care one year later. Otherwise, the study produced results which corroborate the findings of a great deal of the previous work in this field1 i.e. a large number, 31.8% of emergency patients in the current study, of self-referred patients inappropriately utilising the service for basic curative services i.e. extractions, which could be satisfactorily provided at primary care facilities where available.15 Murray and Pearson contend that self-referred patients potentially affect the workload at the hospital, impact on resource utilisation and are an inefficient use of hospital resources.16

One of the issues that emerge from these findings is that symptomatic dental attendance is common at Medunsa Oral Health Centre. An implication of this is that the referral system that operates between Medunsa Oral Health Centre and dental clinics in the Tshwane health district is not effective - 31.8% of emergency patients bypassed it. Further work is required to investigate this referral system. Factors such as accessibility, acceptability, efficiency and effectiveness have been identified as influential in the use of a referral system.17-19

The large discrepancy between the proportions of patients who received treatment than were referred in all clinical units suggests Medunsa Oral Health Centre's internal referral system is ineffective. The reason for this is not clear but treatment provided by students is widely recognised to be inefficient due to such limitations as lengthy waits for instructors and materials, lack of auxiliary staff, poor scheduling systems and general "red tape" built into the teaching system.13 There are, however, other possible explanations.

The large number of patients who require general dental care observed in this study reflects the high levels of untreated dental caries reported in studies of dental caries prevalence in South Africa.20, 21

Average waiting time for treatment in the clinical units

The results of this study show that the average waiting time for treatment in clinical units at Medunsa Oral Health Centre was 81.2 days and ranged between 6 and 184.5 days. It was the shortest for Periodontics (6 days) and longest for Orthodontics (184.5 days).

The average waiting time observed in the current study was significantly higher than the maximum waiting time of 45.8 days that was reported to be acceptable to patients in the City of Turku in Finland.22 Timely access is an important determinant of patient satisfaction.23 Long waiting times have been associated with reduced use of dental services.24

A possible explanation for the long waiting time for treatment may be failure by patients to keep appointments and cancelled appointments. The rate of non-attended dental appointments at Medunsa Oral Health Centre has not been established. A non-attendance rate of 35% has recently been reported at a remote rural dental training facility in Australia.25

Very little was found in the literature on the subject of waiting time for non-emergency dental treatment. Previous research has tended to examine either waiting time for consultation in the equivalent of a diagnostic unit in the current study26 or waiting time for dental treatment with sedation or general anaesthesia.27-29 Further studies on the current topic in populations seeking treatment at dental schools are therefore recommended. Research questions that could be asked include the acceptable waiting time for elective dental care.

The long waiting time for Orthodontics might be related to necessary waiting times to allow the jaw to develop fully.30 It is however difficult to explain the small number of patients treated in relation to the relatively short waiting time for treatment at the periodontics clinic.

Factors associated with receiving elective care

The multivariable analyses of the current study did not find any association between receiving elective curative treatment and gender, age group and patient group.

This finding has previously not been described. Further studies, which take these variables into account, will need to be undertaken. A significant gender difference in the receipt of preventive treatment was however identified at the bivariate level in a dental school patient population in Wisconsin, USA.31

Limitations of the study

A potential threat to the internal validity of this study was the large number of significance test which were carried out. This increases the type 1 error rate, which leads to spurious conclusions.

Another potential threat was the loss to follow up of 8.7% (28/323) of the study sample.

CONCLUSION

The internal referral system that operates at Medunsa Oral Health Centre was assessed as inefficient in the present study.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Mr S Skhosana for his assistance in data collection.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

1. Mojaki ME, Basu D, Letskokgohka ME, Govender M. Referral steps in district health system are side-stepped. S Afr Med J. 2011; 101(2):109. [ Links ]

2. Ncana L. Evaluating the referral system between CECILIA MAKHIWANE HOSPITAL ART unit and its feeder sites, (Zone 2, 8 and 13 clinics 2010). [Masters Thesis]. Stellenbosch University, 2010. [ Links ]

3. Mashishi MM. Assessment of Referrals to a District Hospital Maternity Unit South Africa. [Masters Thesis]. University of the Witwatersrand, 2010. [ Links ]

4. Visser R, Bhana R, Monticelli F. National Health Care Facilities Baseline Audit, National Summary Report September 2012 Revised February 2013, Health Systems Trust. Available: www.doh.gov.za/docs/reports/2013/Healthcare.pdf [Accessed 25 September 2013]. [ Links ]

5. Bhayat A, Cleaton-Jones P. Dental clinic attendance in Soweto, South Africa, before and after the introduction of free primary dental health services. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003; 31(2): 105-10. [ Links ]

6. Harkinson BN, Cleaton-Jones PE. Analysis of attendance rates at Soweto dental clinics 1995-2002. S Afr Dent J 2004; 59(4): 147-9. [ Links ]

7. Lesolang RR, Motloba DP, Lalloo R. Reasons for tooth extraction at the Winterveldt Clinic: 1998-2002. S Afr Dent J 2009; 64:214-8. [ Links ]

8. Medical University of Southern Africa. Faculty of Dentistry Calendar Volume III 2002. [ Links ]

9. University of Limpopo (Medunsa Campus). Faculty of Dentistry Calendar Volume III 2006. [ Links ]

10. Nkoatse NC. Fixed prosthetic status and need of patients presenting at Medunsa Oral Health Centre. [Masters Thesis]. University of Limpopo (Medunsa Campus), 2008. [ Links ]

11. Wanjau J, Mthethwa R, Sethusa PS. Profile of orthodontic patients consulting at Medunsa Oral Health Centre. IADR 2009 (Mombasa). [ Links ]

12. Maaga MA. Profile of patients treated in Careline Clinic of the Medunsa Oral Health Centre. [Masters Thesis]. University of Limpopo (Medunsa Campus), 2013. [ Links ]

13. Singh AS, Mohamed A, Bouckaert MM. A clinical evaluation of dry sockets at the Medunsa Oral Health Centre. South African Dental Journal 2008; 63(9):490-3. [ Links ]

14. Department of Health. Norms, Standards and Practice Guidelines for Primary Oral Health Care: Department of Health, 2005. [ Links ]

15. Murray SF, Pearson SC. Maternity referral systems in developing countries: Current knowledge and future research needs. Social Science & Medicine 2006;62: 2205-15. [ Links ]

16. Middleton KR, Hing E. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2004 Outpatient Department Summary, CDC Advance Data 2006; 373(3):130-3. [ Links ]

17. Hensher M, Price M, Adomakoh S. Referral Hospitals. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, et al., editors. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd edition. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2006. [ Links ]

18. Akande TM. Referrals system in Nigeria: Study of a tertiary health facility. Annals of African Medicine 2004; 3(3):130-3. [ Links ]

19. Formicola AJ, Myers R, Hasler JF et.al. Evolution of dental school clinics as patient care delivery centres. Journal of Dental Education 2006; 72(2) Supplement: 110-17. [ Links ]

20. Singh S. Dental caries rates in South Africa: implications for oral health planning. South Afr J Epidemiol Infect 2011; 26(4) (Part II): 259-61. [ Links ]

21. van Wyk PJ, van Wyk C. Oral health in South Africa. International Dental Journal 2004;54:373 -7. [ Links ]

22. Tuominen R, Eriksson A.-L. Patient experiences during waiting time for dental treatment. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 2012; 70(1): 21-6. [ Links ]

23. Welch JD, Bailey NormanT J. Appointment systems in hospital outpatient departments. The Lancet 1952; 259(6718):1105-8. [ Links ]

24. Marino R, Wright C, Schoefield M, Calache H, Minichello V. Factors associated with self-reported use of dental services among older Greek and Italian immigrants. Spec Care Dentist 2005; 25:29-36. [ Links ]

25. Lalloo R, McDonald JM. Appointment attendance at a remote rural dental training facility in Australia BMC Oral Health 2013; 13: 36. [ Links ]

26. Al-Mudaf BA, Moussa M.A.A, Al-Terky M.A, Al-Dakhil G.D, El-Farargy A.E, Al-Ouzairi S.S. Patient satisfaction with three dental speciality services: A centre-based study. Medical Principles and Practice 2003; 12:39-43. [ Links ]

27. Badre B, Serhier Z, El Arabi S. Waiting times before dental care under general anesthesia in children with special needs in the Children's Hospital of Casablanca. Pan African Medical Journal 2014; 17:298. [ Links ]

28. Katre, A.N., 2014. Assessment of the correlation between appointment scheduling and patient satisfaction in a pediatric dental setup. International Journal of Dentistry, 2014. [ Links ]

29. Lewis CW, Nowak AJ. Stretching the safety net too far: waiting times for dental treatment. Pediatric Dentistry 2002; 24(1):6-10. [ Links ]

30. McNair A, Morris D, editors. Managing the Developing Occlusion: A Guide for Dental Practitioners. British Orthodontic Society, 2010. [ Links ]

31. Okunseri C, Bajorunaite R, Mehta J, Hodgson B, Iacopino A. Factors associated with receipt of preventive dental treatment procedures among adult patients at a dental training school in Wisconsin, 2001-2002. Gender Medicine 2009; 6:272-6. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Sibusiso Rockfort Mthethwa

Medunsa Campus,

PO Box D24,

Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University 0204 .

Tel: 012 521 5888.

Fax: 012 512 4274.

Email: rocky.mthethwa@smu.ac.za