Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562

Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.71 n.1 Johannesburg Feb. 2016

RESEARCH

The perceptions of South African dentists on strategic management to ensure a viable dental practice

L SnymanI; S Ε van der Berg-CloeteII; J G WhiteIII

IBChD, PG Dip Dent (Clinical Dentistry), PG Dip Dent (Practice Management), PGCHE, MBL. Senior Lecturer: Department of Dental Management Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Pretoria

IIBChD, PG Dip Dent (Community Dentistry), MBA. senior Lecturer: department of dental management Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Pretoria

IIIBChD, BChD (Hons), DTE, MBA, PhD. head of department: dental management sciences, school of dentistry, University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: How do dentists perceive the influence of the external environment on, and what is their confidence in, planning the strategic management of their practices?

METHODS: A cross-sectional survey using an anonymous online questionnaire was conducted among private dental practitioners, members of the South African Dental Association. Stata release 11 was used for descriptive data analysis, including determination of frequencies

RESULTS: The majority of the respondents work 40-44 hours, see more than 70 patients per week and are fairly satisfied with those numbers. Only 27.56% of practices confirmed written vision/mission statements. One third (33.78%) were only moderately confident they could plan and execute strategies to ensure a viable practice. Almost a tenth (8.11%) does not feel confident at all. Medical schemes, disposable income of patients and dentist-patient communication were the most significant challenges. Clinical practice was more satisfying than the business side

CONCLUSION: Dental practices are increasingly complex, with a myriad of challenges. Ideally the dentist as owner/ manager/leader, should be able to strategise management of the external and internal environments to achieve the vision, mission and objectives of the practice. Dental schools, in collaboration with SADA, should work towards equipping dentists with the necessary management and strategic thinking skills to ensure success

Key words: Dental practice management, strategic management, External forces

INTRODUCTION

The business environment in which dental practices operate is becoming increasingly complex, and to ensure a viable and successful career, dentists should be equipped with management skills as well as clinical expertise.1-3 Dental practitioners in the private sector are facing a host of challenges. Guaranteed medical fund pay-outs declined from 15% in the early nineteen nineties to approximately 2% in 2012.4,5 Changing disease patterns, increased consumerism, advancing technology and unfavourable exchange rates affecting the import of dental materials complicate the situation even further.1,6 Three out of four American dental practices have reported declines in production levels since the 2008 recession.7 The situation in South Africa is not known but it might just be that our colleagues are finding themselves in similar situations.

Unlike other business and corporate leaders who are prepared through formal business training to succeed in a complex economic environment, dentists receive little or no such training in dental school.6,8 According to Levin,9 many dentists practise for years without having a clear strategy or specific goals of how to keep the practice growing and succeeding; they merely go to work, hoping to have a great day with few problems. Unfortunately in today's competitive dental economy, dentists can no longer afford such an attitude. Good management skills and especially strategic thinking skills, are becoming a prerequisite for success.

The profitability of small businesses like dental practices is influenced by the market environment in which the industry (dentistry) operates, as well as by the individual competitive market forces.10 Crafting and executing strategy are the heart and soul of managing a business enterprise.11 Insightful analysis of a business's external environment is a prerequisite for crafting a strategy that is an excellent fit with the situation, is capable of building competitive advantage, and which holds good prospects for boosting business performance.11-13 If elements of competition can be defined, strategies can be formulated to better deal with market forces. Businesses that explicitly formulate strategies usually perform better in a competitive environment.13,14 There is also evidence that strategic planning by health care organisations improves performance.15 According to Lau16 strategic planning is one of the key business concepts applicable to the successful dental practice, and "just as a dentist diagnoses and treatment plan patients, so too should his business "diagnose and treatment plan " its future". One often hears colleagues in private practice complain about how difficult it has become to survive and to maintain a viable practice, given all the challenges that they have to face. The question that surely comes to mind is how skilled and confident are dentists to plan and execute strategy to ensure the viability of their practices? Do they even engage in strategic planning or are they merely working year after year just hoping for the best?

AIM

The study set out to investigate the perceptions held by dentists regarding the influence of the external environment on the strategic management of a dental practice as well as their confidence in being able to plan and execute strategy to ensure the viability of those practices. The objectives were to determine:

- how busy are dentists in South Africa,

- how strategically orientated they are,

- what external forces/challenges dentists perceive to have the most significant effect on practices in South Africa, and

- what strategies dentists employ to counteract these external forces/challenges.

METHODS

Permission to conduct the research study was obtained from the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria (160/2014). Data for this study was collected via a self-developed questionnaire that was hosted online at SurveyMonkey (www.survey-monkey.com). A cover letter that explained the purpose of the study and which invited dentists in private practice to participate was sent by the South African Dental Association (SADA) to all members on SADA's electronic database. The cover letter contained the link to the online questionnaire. Those who agreed to participate were routed via a link in the letter to the questionnaire. Due to the initial low response rate two additional reminders were sent and the due date for participation was extended by four weeks.

The questionnaire comprised 29 questions, of which only three were qualitative in nature where dentists had to express their opinions. The questions were clustered in different sections to elicit demographic information, details of the practice, the busyness of the practice, strategic orientation of the dentist, and strategic issues in the practice. Most questions required respondents to select an answer from multiple categories.

The software package Stata Release 11 was used for data analysis which was mainly descriptive in nature and included a determination of frequencies. The Chi-square / Fisher Exact test was used to test for associations between selected demographic, practice characteristic and strategic approach variables. Significance was set at the 0.05 level.

RESULTS

The survey was sent to 3367 SADA members via e-mail. A total of 252 responses were received by the final, extended cut-off date, constituting a 7.48 % response rate. It was decided to eliminate 18 respondents who completed only the demographic details, but failed to answer any additional questions. Analysis was therefore conducted on 234 (6.95%) valid responses. These 234 responses included general dentists (n=221) and specialists (n=13). Although the apparent response rate is very low, one should take into consideration that the SADA database contains the e-mail addresses of members that are working in the public sector, members outside the borders of South Africa, Oral Hygienists as well as Dental Therapists It is therefore not really possible to determine or comment on the response rate when it was only dentists in private practice who were invited to participate.

Demographics (Table 1)

The majority of the respondents were male (67.09%), and ranged in age between 31 and 60 years of age. Most of the respondents completed their studies at the University of Pretoria (44.44%), followed by the University of Witwatersrand (17.52%) and the University of Western Cape (15.38%). A total of 94.44% of respondents were general dental practitioners, while only 5.56% were dental specialists. Among the 13 dental specialists who responded, six were Orthodontists, three were Maxillo- Facial and Oral surgeons, two were Periodontists and two Prosthodontists. The majority of respondents had their primary practice located in Gauteng (38.89%), followed by the Western Cape (17.52%) and Kwazulu-Natal (16.24%). The business model of the majority of respondents was a solo dental practice (59.66%), while 20.17% indicated that they operate in partnerships and 20.17% operated in other business models which mainly included being in association with other dentists or working for Medicross or Intercare.

Busyness of the practice

Almost a third of the respondents (32.76%) work on average between 40 to 44 hours per week, while 20.26% work between 45 and 49 hours per week, 13.36 % work 50 to 54 hours per week and a total of 6.9% of respondents indicated that they work more than 55 hours per week (Figure 1).

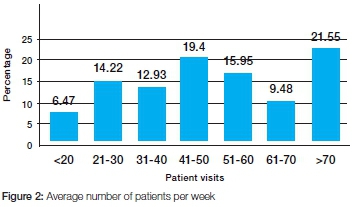

Results indicate that the majority of respondents (21.55%) see on average more than 70 patients per week, and that 19.4% of respondents see 41 to 50 patients per week (Figure 2). Only a small percentage of respondents, namely 6.47%, see less than 20 patients per week.

When asked about the busyness of the practice, almost half of the respondents (49.14%) indicated that they were satisfied with the number of patients, while 16.38% indicated that they are too busy to accommodate all the patients requesting treatment. By contrast, just over a third of respondents (34.48%) replied that they are not busy enough and need more patients (Figure 3).

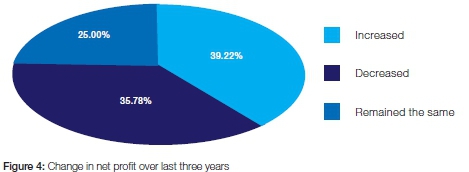

Respondents were divided in their opinion on the profitability of their practices (Figure 4) with 39.22% indicating that their net profit increased over the past three years, and almost an equal percentage of respondents (35.78%) indicating that their net profit decreased over the last three years. A quarter of respondents (25.00%) indicated that their net profit remained the same over the last three years.

Strategic orientation

Just more than a quarter of respondents (27.56%) had a written vision/mission statement for their practice. When asked how confident they feel to plan and execute strategy/strategies to ensure a viable practice, the majority of respondents (33.78%) were only moderately so, while almost a tenth of respondents (8.11%) did not feel confident at all. However, 6.67% of respondents did indicate that they were extremely confident in strategizing for a viable practice (Figure 5).

No statistically significant associations were demonstrated between demographic variables and the existence of a vision/mission statement, or between demographic variables and the confidence of respondents to plan and execute strategy (p>0.05). Furthermore, no statistically significant association was demonstrated between the existence of a vision/mission statement and the busyness of the practice (p=0.281).

Respondents who indicated that they had a written vision/ mission statement were asked to answer additional questions regarding their practices' strategic orientation (Table 2). Most of the respondents "agree" or "strongly agree" that their staff understand the vision/mission of the practice, and that the goals of the practice reflect the mission. The goals of the practice are set both as short-term (1 year) and longer term (3-5 years) objectives, describe quantifiable and measurable targets and the practice systematically measures actual performance versus goals. The majority of respondents "agree" or "strongly agree" that having a clear strategy is critical for the success of the practice.

Identifying strategic issues

Respondents were asked to rate on a scale of 1 to 5 (where 1 is "least impact" and 5 is "most impact") the most relevant challenges that they face in practice. They were somewhat divided in opinion on the challenge posed by the proposed National Health Insurance (NHI), with 26.09% rating it as 1 ("least impact") and almost an equal percentage (23.37%) according a rating of 5 ("most impact") (Table 3). Disposable income of patients is seen as a major challenge with 48.91% of respondents rating this as a 5 and 28.80% rating it a 4. The pay outs of Medical schemes are probably the most serious challenge faced by respondents, receiving a rating of 5 by 50.54% and a 4 by 21.20% of respondents. Dentist-patient communication also featured as important with 22.83% of respondents recording a rating of 5 and 22.28%, a rating of 4. "Other dentists" (competitors) do not seem to be a challenge with 32.07% of respondents considering this deserving of either a 1 or a 2.

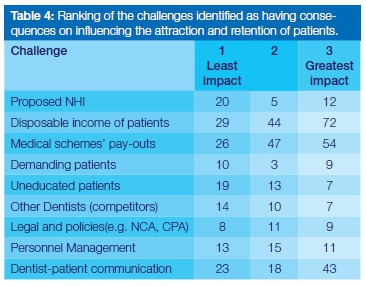

Respondents were asked to identify and to rate in importance (where 1 is "least impact" and 3 is "greatest impact"), the three most relevant challenges influencing the attraction and retention of patients in their practices. The disposable income of patients is seen as the challenge having the greatest impact (72 votes), followed by medical schemes' pay-outs (54 votes) and dentist-patient communication (43 votes) (Table 4).

When asked what strategies they have in place to counter the three challenges identified as most significantly affecting the attraction and retention of their patients, a number of respondents confessed that they have none (n=27) or simply did not answer the question (n=6). Other respondents indicated that in dealing with problems of limited disposable income, they try to educate patients on the value (medical/social) of a healthy/attractive mouth, charge rates according to patient demographics, try to work within a patient's budget, do the best treatment that patients can afford, do less costly work, have payment plans available and allow down payments, give written quotations and discuss alternative treatment options with patients, help with interest-free finance and assist patients to procure loans from First Health Finance.

The pay outs of medical schemes were also an important challenge faced by respondents who reported a variety of strategies. Some indicated that they charge fees that medical schemes will pay, that authorization is secured from schemes before treatment, that the medical scheme benefits are ascertained prior to treatment. Further, practitioners reported that they try to know the rules of the different medical schemes, and that there is a regular follow up with medical schemes regarding payments. Other respondents clearly stated that they have cash only practices to avoid working with medical schemes, and simply require patients to pay first and then to claim from the medical schemes. Some participating dentists educate patients as to where funders stand regarding expensive choice treatment and then explain why and how their fees were higher than those that medical schemes were prepared to reimburse, while others indicated that they stay involved with SADA and engage in SADA activities as a group to stand up against the challenge of disparity between fees and allowances.

Strategies employed by respondents to counteract the challenge of dentist-patient communication included engaging more with patients on their expectations, spending more time with patients discussing treatment plans and securing the trust of patients in proposed treatments, making use of intra-oral cameras, study models and visual communication to enhance understanding from patients, using the initial visit to build good dentist-patient rapport, training personnel to be able to answer patients' questions, having detailed communication policies in place for patient marketing and education, and to regularly attend management and communication courses. One respondent observed that he/she employs Xhosa-speaking personnel to translate for patients and to help in their dental education.

The majority of respondents (35.87%) rated their satisfaction with the business aspect of their practices as only 3 on a scale from 1 to 5 where 1 is "not satisfied at all" and 5 is "completely satisfied" (Table 5). Only 7.07% rated this evaluation a 5. In contrast, 52.17% of respondents rated their satisfaction with the clinical aspect of the practice a 4 and 32.61% gave this a 5. Respondents are clearly more satisfied with the clinical, than with the business aspect, of the practice.

DISCUSSION

Strategic planning is a key business concept applicable to the successful dental practice16 and the current study is the first in South Africa that attempts to investigate the perceptions of dentists on strategic management to ensure a viable dental practice amidst the challenging external environment. Due to the low response rate, the results of this study should not be generalised to the private dentist population of South Africa. An additional limitation of the study was the online nature of the questionnaire which led to exclusion of dentists who do not have internet access. Bias could also have been introduced by using a convenience sample of dentists who are members of SADA, thereby excluding non-members who possibly may have a different perspective, not reflected by the results of this study. One should also be cautious in drawing definite conclusions, since some of the questions had a very high number of non-responses (as many as 50). Nevertheless, the study does present an indication of the challenges currently faced by private practitioners in South Africa.

The majority of the respondents work 40-44 hours per week, see more than 70 patients per week and are fairly satisfied with the number of patients they see. Only 34.48% of respondents indicated that they are not busy enough and need more patients, in contrast with research done in 1999 among private dental practitioners in South Africa which indicated that 55.8% of respondents were not sufficiently busy and required more patients.17 Although the current study does not differentiate between general dentists and dental specialists, results are in line with findings from the American Dental Association Health Policy Resources Centre's Survey of Dental Practices which found 37% of general dentists and 36% of dental specialist describing themselves as "not busy enough" in 2012.18 It has been recommended over the years that dentists should do more "comprehensive dentistry", deliver an exceptional service, and also improve their communication and marketing skills in order to increase patient flow and net profit.1,7,19,20 The mere fact that the respondents of this study are fairly satisfied with the number of patients and that the majority indicated that their net profit increased, can perhaps be an indication that more dentists are focusing on these types of recommendations. Their responses regarding strategies employed to counteract challenges that influence attraction and retention of patients strengthen this assumption even further.

The fact that 35.78% of respondents indicated that their net profit decreased in the last three years can however be of concern. Although the reasons for this should be properly investigated, it might be assumed that one could be increasing costs. It is a well-known fact that it is becoming more difficult to contain practice overheads due to rising supply costs (e.g. exchange rate of the Rand) and competitive labour markets.4,21 Rising expenses make it more difficult for solo practitioners to be competitive in the marketplace, and cause people to question whether this practice mode will remain viable in the future.22 Research has indicated that the number of solo practices in the USA is declining steadily, and this trend is expected to continue as more cost-efficient larger practices predominate.23,24

Group practices and corporate practices are new delivery models that are on the increase in the USA.22,25,26 Economies of scale arise when activities can be performed more cheaply at larger volumes and from the ability to distribute certain fixed costs over a greater sales volume.27 Research has indeed shown that there might be some advantages of scale in larger dental practices.28 The majority of respondents in this study (59.66%) still operate as solo practices, but the question remains as to whether this is still a viable practice model. SADA undertook research in 2014 in conjunction with KPMG to determine the most viable future business models (e.g. single practice, group practice, franchise practice and affiliated practice) for the South African market amidst the economic shifts and the prospective NHI. Outcome and recommendations of this research are still being awaited, but the cost advantages of larger group practices should certainly be considered by new dentists entering the South African market.

According to Montgomery,29 strategy guides the development of the identity and purpose of the business over time. Businesses that explicitly formulate strategies usually perform better in a competitive environment.13,14 There is also evidence that strategic planning by health care organisations improve performance.15 The importance of strategic leadership30,31 and the value of vision and mission statements32-35 have been well documented in the literature. Yet, only 27.56% of respondents in this study confirmed the presence of written vision/mission statements for their practices. Results indicated further that nearly 60% of respondents feel only moderately or less confident to plan and execute strategy/strategies to ensure a viable practice. This can also be another reason for the decrease in net profit as indicated by 35.78% of respondents. A lack of confidence to plan and execute strategy/strategies to ensure a viable practice can be attributed to the fact that dentists receive very little or no business training in dental schools. To address this shortcoming, dental schools will have to include business training as part of the curriculum and, in collaboration with SADA, could offer courses in strategic management to dentists. No statistically significant association was demonstrated in this study between the existence of a vision/mission statement and the busyness of the practice (p=0.281). However, it is still recommended that dentists, as the owners/managers/ leaders, should be able to accommodate and integrate both the external and internal environments of the practice in formulating and implementing a strategy to ensure that the vision, mission and strategic objectives are achieved, ultimately leading to superior practice performance.11,31

Medical schemes' pay outs, disposable income of patients and dentist-patient communication were identified as the most significant challenges faced by respondents, also affecting patient attraction and retention most significantly. The proposed NHI was also identified as a significant challenge by some respondents, probably due to uncertainty on how it will affect the patient base in future. Medical schemes' pay-outs for dental care have declined steadily over the last almost 30 years, from 12.6% in 19851 to a mere 2.6% in 2013.36 The frustration of having to deal with a lot of administrative hassles, late payments from funds, difficulty in obtaining authorisation for procedures etc., probably contribute to the identification by some dentists of medical schemes as the most significant challenge facing practice. The constraints of limited disposable income of patients also pose a huge challenge, and respondents rated it the challenge that most significantly affects the attraction and retention of patients. Although the disposable income of South Africans has actually increased, household debt has risen to 75.8% of disposable income in the second quarter of 2013.37 Rising inflation, higher petrol and electricity costs, and escalating property rates and taxes put consumers under even more pressure to carefully consider their spending, and often dental treatment might be low on their priority list. Although there are no clear-cut answers on how to deal with these challenges, it seems that respondents are finding ways to cope, mainly by concentrating on educating patients regarding the value of good oral health, doing work that patients can afford, knowing the rules of the different medical schemes, and regularly following up with medical schemes regarding payments. Good dentist-patient communication has been proven important in providing dental care, and leads to increased patient satisfaction and motivation, just as inadequate or negative dentist-patient communication can create barriers to care and other undesirable outcomes.38-41 It is clear that respondents find dentist-patient communication a significant challenge in practice. The multicultural population of South Africa, together with our eleven official languages, probably creates additional barriers to good communication. While some respondents realize the importance of taking time to build good patient rapport, together with the use of visual aids in improving communication, there are other respondents who simply don't know how to deal with this challenge. These respondents will clearly benefit from additional training in communication skills and techniques, a gap that can again be filled by dental schools and by SADA.

Respondents in this study appear to be more satisfied with the clinical aspect of practice than with the business aspect. This came as no real surprise, since similar results have been reported by other researchers.10,42 Although the reason for this finding was not investigated in this study, it can probably again be attributed to the fact that dentists receive little or no business training in dental school, leaving them not prepared to manage a practice, and ultimately leading to dissatisfaction with the business aspect of dentistry. Traditionally dentistry is seen as a "caring profession", it is about helping people and therefore the management of patients and producing high quality, technically demanding dentistry leads to more job satisfaction than managing the business.42 Learning business skills by trial and error, as respondents in one study stated, can be quite a painful experience.43

CONCLUSION

Many dentists are not equipped to handle the strategic planning which has become essential to manage the challenges of contemporary dental practice. Dental schools, in collaboration with SADA, should work towards training students and dentists in the necessary management skills, especially strategic thinking skills, to ensure success amidst the challenging external environment.

Acknowledgement: We would like to acknowledge Prof PH Becker (Biostatistician, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria) for his help with the statistical analysis of results.

Declaration: No conflict of interest declared.

References

1. White JG. Interacting forces influencing private dental practices in South Africa: Implications for dental education. J Dent Assoc SA. 2008;63(2):80-5. [ Links ]

2. Dunning DG, Lange BM, Madden RD, Tacha KK. Prerequisites in behavioral science and business: opportunities for dental education. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(1):77-81. [ Links ]

3. Willis DO. Using competencies to improve dental practice management education. J Dent Educ. 2009;73(10):1144-52. [ Links ]

4. Van Wyk P. Dentistry is heading for a crisis (Tandheelkunde gaan 'n krisis word). Beeld. 2012 January 7. [ Links ]

5. Van Wyk PJ, White JG. Impact of Medical Schemes Act on the utilisation of dental services. XXXVII Scientific Congress of the International Association of Dental Research (South African Division); 11 & 12 September; Cape Town, South Africa, 2003. [ Links ]

6. White JG. Development, implementation and evaluation of a curriculum for teaching relation communication skills in Dentistry [Doctoral Thesis]. Pretoria: University of Pretoria; 2006. [ Links ]

7. Levin RP. Transform your practice and increase production. Dent Econ. 2013;103(10):23-4. [ Links ]

8. Levin RP. Leading the patient-centric practice. Dent Econ. 2014;104(10):94. [ Links ]

9. Levin RP. Avoiding today's biggest practice mistakes. Dent Econ. 2015;105(2):34. [ Links ]

10. Hughes D, Landay M, Straja S, Tuncay O. Application of a classical model of competitive business strategy to orthodontic practice. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;110(4):405-9. [ Links ]

11. Thompson AA, Strickland AJ, Gamble JE. Crafting And Executing Strategy: The quest for competitive advantage: concepts and cases. 17th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin; 2010. [ Links ]

12. Grant RM. Contemporary Strategy Analysis. 7th Edition West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2010. [ Links ]

13. Porter ME. What is strategy? Harv Bus Rev. 1996;74(6):61-78. [ Links ]

14. Hamel G. Strategy innovation and the quest for value. Sloan Manage Rev. 1998;39(2):7-14. [ Links ]

15. Trinh HQ, O'Connor SJ. The strategic behaviour of U.S. rural hospitals: A longitudinal and path model examination. Health Care Manage Rev. 2000;25(44):48-64. [ Links ]

16. Lau CS. Strategic Planning: A guide to success. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2001;29(3):211-4. [ Links ]

17. White JG, Barnard JT. Dental employment: A study to determine the effect of busyness on willingness to treat patients at a capitation fee. J Dent Assoc SA. 1999;54(5):175-9. [ Links ]

18. Vujicic M, Munson B, Nasseh K. Despite economic recovery, dentist earnings remain flat. Health Policy Resources Center Research Brief. American Dental Association, October 2013. Available from: http://www.ada.org/sections/professionalResources/pdfs/HPRCBrief_1013_4.pdf. Accessed May, 08, 2015. [ Links ]

19. Jameson C. The model of success. J Dent Assoc SA. 2012;67(9):518-22. [ Links ]

20. Wahl P, Hegarty G. 2 Rules for practice prosperity. Dent Econ. 2007;97(4):100-2. [ Links ]

21. Kao RT. Dentistry at the crossroads. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2014;42(2):91-5. [ Links ]

22. Parker MA. New practice models and trends in the practice of oral health. N C Med J. 2012;73(2):117-9. [ Links ]

23. Vujicic M, Israelson H, Antoon J, Kiesling R, Paumier T, Zust M. A profession in transition. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(2):118-21. [ Links ]

24. Diringer J, Phipps K, Carsel B. Critical trends affecting the future of dentistry: assessing the shifting landscape. Prepared for American Dental Association. May 2013. Available from: http://www.ada.org/sections/professionalResources/pdfs/Escan2013_Diringer_Full.pdf. Accessed May 08, 2015 [ Links ]

25. Guay AH, Wall TP, Petersen BC, Lazar VF. Evolving trends in size and structure of group dental practices in the United States. J Dent Educ. 2012;76(8):1036-44. [ Links ]

26. Bailit H. Dentistry is changing: Leaders needed. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(2):122-4. [ Links ]

27. Ehlers T, Lazenby K. Strategic management: Southern African concepts and cases. 3rd ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers; 2010:181. [ Links ]

28. Chen L. A study of the production technology of general dental practice in the U.S. [Doctoral thesis]. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut; 2010. [ Links ]

29. Montgomery CA. Putting leadership back into strategy. Harv Bus Rev. 2008;86(1):54-60. [ Links ]

30. Ireland RD, Hitt MA. Achieving and maintaining strategic competitiveness in the 21st century: The role of strategic leadership. The Academy of Management Executive. 1999;13(1):43-57. [ Links ]

31. Jooste C, Fourie B. The role of strategic leadership in effective strategy implementation: Perceptions of South African strategic leaders. SA Bus Rev. 2009;13(3):51-68. [ Links ]

32. Bart CK, Bontis N, Taggar S. A model of the impact of mission statements on firm performance. Management Decision. 2001;39(1):19-35. [ Links ]

33. Mullane JV. The mission statement is a strategic tool when used properly. Management Decision. 2002;40(5):448-55. [ Links ]

34. Blanchard K, Stoner J. The vision thing: Without it you'll never be a world-class organization. Leader to Leader. 2004;2004(31):21-8. [ Links ]

35. Kantabutra S, Avery GC. The power of vision: Statements that resonate. J Bus Strategy. 2010;31(1):37-45. [ Links ]

36. Council for Medical Schemes Annual Report 2013/14. Available from: http://www.medicalschemes.com/files/Annual%20Reports/AR2013_2014LR.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2015. [ Links ]

37. Maswanganyi, N. Growth in household spending, but debt remains high. Business Day Live, September 11, 2013. Available from: http://www.bdlive.co.za/economy/2013/09/11/growth-in-household-spending-but-debt-remains-high. Accessed May 13,2015. [ Links ]

38. Rozier RG, Horowitz AM, Podschun G. Dentist-patient communication techniques used in the United States: The results of a national survey. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(5):518-30. [ Links ]

39. Jameson C. Great communication equals great production. 2nd ed. Oklahoma: PennWell Corporation; 2002. [ Links ]

40. Yamalik N. Dentist-patient relationship and quality care 3. Communication. Int Dent J. 2005;55(4):254-6. [ Links ]

41. Mazzei A, Russo V, Crescentini A. Patient satisfaction and communication as competitive levers in dentistry. The TQM Journal. 2009;21(4):365-81. [ Links ]

42. Calnan M, Silvester S, Manley G, Taylor-Gooby P. Doing business in the NHS: exploring dentists' decisions to practice in the public and private sectors. Sociol Health Illn. 2000;22(6):742-64. [ Links ]

43. Fischer JE, Marchant T. Owners' insights into private practice dentistry in New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. Aust Dent J. 2010;55(4):423-9. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Lorraine Snyman

Department of dental management sciences, school of dentistry, University of Pretoria

P.O. Box 1266, Pretoria, 0001, South Africa

Tel: +27 12 319 2616 , Fax: +27 12 319 2146

E-mail: lorraine.snyman@up.ac.za