Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562

Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.70 n.9 Johannesburg Oct. 2015

RESEARCH

Dental Caries status in six-year-old children at Health Promoting Schools in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

M ReddyI; S SinghII

IM.Dent (Dental Public Health). Lecturer, Discipline of Dentistry, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal

IIAcademic Leader Discipline of Dentistry, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal

ABSTRACT

The 2003 National Children's Oral Health Survey indicated that 35.2% of six-year-olds in KwaZulu-Natal were caries free and only 40% had received dental treatment. The aim of the present study almost ten years later was to investigate these data in six-year-old children at Health Promoting Schools in KwaZulu-Natal.

METHODS: A quantitative, epidemiological explorative study was conducted on a sample of 345 Grade 1 learners attending 23 schools, selected by statistical sampling from the eleven districts of KwaZulu-Natal. The World Health Organisation DMFT Tool (1994) was used to record the data.

RESULTS: The caries rate of the sample was 73% (ie. 27% caries free) and the mean dmft was 3.65. The average dmft per school ranged from a high of 6.8 to a low of 1.1, both from rural districts. 94% of the learners required treatment, the majority (90%) needing preventive care. The Unmet Treatment Need (UTN) was 97%.

CONCLUSIONS: The number of caries free six year old children in KwaZulu-Natal has declined further compared with ten years ago. Dental caries is still a major public health problem. An effective and efficient oral health promotion programme will do much to instil simple healthy behaviours at an early age.

Keywords: dental caries prevalence, health promoting schools, oral health promotion, oral health services, treatment needs

INTRODUCTION

Three national studies have been conducted in South Africa. The first by Williams in 1984 was on dental health status of 12-year-olds.1 The second study determined oral health status of adults and children in the five main cities in South Africa in 1988/89, and the third study in July 1999 to June 2002 focused on children between the ages of 4 and 15 years.2-3 The latter two studies were conducted by the National Department of Health.

The National Children's Oral Health Survey (2003) indicated that only 35.2% of six-year-olds were caries free in KwaZulu-Natal and 40% received dental treatment.2 A comparison of results for six-year-olds in the Durban region for both of the Department of Health National surveys indicated that there was a decrease in mean dmft from 3.89 (1988) to 3.42 (2002) and decayed teeth from 3.58 (1988) to 2.79 (2002) with no difference in results for the number of filled teeth (0.15).2-3 One of the new National Goals for six-year-olds for 2020 is to increase the percentage of this age group who are caries free to 60% in addition to having fissure sealants placed in 60% of these children.4

Dental caries is influenced by multiple factors such as diet, socio-economic status and the availability of oral health services. The affliction has been identified as the most widespread condition affecting children in South Africa. The inevitable dental pain and discomfort result in the loss of school days and dental caries has become a major public health concern because of the burden it places on public health services.4-5

Evidence in the literature suggests that intervention strategies that are currently employed are standardised and not evidence-based for diverse populations. These interventions are therefore not producing the desired outcomes resulting in the failure of the current National Oral Health plans in South Africa.4 Consequently, the prevalence of caries in children has not been adequately addressed through policy and service delivery.6

There is a paucity of information available on dental caries status in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, particularly in the rural areas where the majority of the population live.7-8 The last National Oral Health Survey, conducted ten years ago, established that there was an increasing rate in caries in six-year-olds especially in the primary dentition. The school setting, where education and health programmes can have a great impact by influencing learners at important stages in their lives - childhood and adolescent, was chosen for this study.9 The purpose was to assess the dental caries status of a sample of six-year-old learners at health promoting schools in KwaZulu-Natal and to establish new baseline information prior to the implementation of an oral health promotion programme at these schools.

METHOD

The study sample (n=345) comprised of Grade 1 learners attending 23 schools that were selected from the eleven districts of KwaZulu-Natal using multistage cluster sampling. Schools were selected according to districts and then quintiles. Using a sample size calculator, a power calculation was done with a confidence level of 95% and a confidence interval of 5, selecting 345 learners for caries assessment from a total of 2402 Grade 1 learners, a selection that translated to an average of 15 learners per school. Systematic random sampling was used to identify participants by randomly selecting learners from approved parental consent forms that were provided to each school. The reporting of the status of the tooth focused on primary teeth, given the age group that was examined, and given the presence of only a few permanent teeth. However permanent teeth were included for the assessment of treatment needs, to report on caries arrest and sealant care for this age group.

This was an epidemiological explorative study using quantitative data. The World Health Organisation DMFT Tool (1994) was used to record the data.

Gatekeeper permission was obtained from the Department of Education and the principals of the selected schools. The study was approved by the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (HSS/0509/013D) and ethical guidelines was used to ensure confidentiality in the management of data.

An information sheet and parental consent forms in English and Zulu were sent to all parents of Grade 1 learners at selected schools requesting consent for dental examination. Assent was obtained from the learners prior to the examination. Examinations were conducted only on learners who were willing and whose parents had granted consent. Field assistants were calibrated for visual dental caries diagnosis using the method developed by the British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry (BASCD) with intraoral photographs to a kappa score of 0.90 for inter examiner reliability.10 Intra examiner reliability was maintained according to World Health Organisation standards for oral health surveys by repeating every fifth oral examination completed.11 A tooth was recorded as decayed only if there was a visible break in enamel and missing teeth were scored only if it could be ascertained that the loss was due to caries. There was no treatment score for arrested decay with no pain on deciduous teeth.

Non-invasive oral examinations, using only a wooden spatula for retraction, were performed on learners sitting on a chair in good natural light with their heads slightly tilted, either forwards or backwards, and the examiner seated in front. Optimal infection control procedures were maintained by using new spatulas and gloves for each patient and having the examiner wear a mask. Learners requiring further dental management were referred to the nearest dental clinic.

Data was recorded on the World Health Organisation DMFT tool and transferred onto Excel. The statistical package used for data analysis was SPSS version 21.0.

RESULTS

The sample of Grade 1 learners (n =345) had a ratio of males to females of approximately 1:1 (51.6%:48.4%). The mean age of the participants was 6.8 years with 96.7% in the six to eight year old age group. Fourteen (60.9%) of the schools were in rural areas, six (26.1%) in the peri-urban and three (13%) in urban areas.

The Pearson Chi Square Test showed no significant differences in the results of the repeated tests for intra examiner reliability, confirming repeatability.

Of the total study sample (345) of learners, 130 (37.7%) male learners presented with caries compared with 114 (33.0%) female learners. The Fischer's Exact Test (p-value 0.196) implied that there was no significant relationship between gender and the number of decayed teeth. The prevalence of caries between the rural and the urban learners also showed no significant difference.

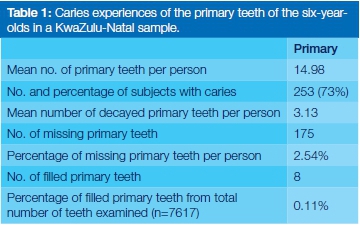

The caries experiences of primary teeth of six-year-olds are shown in Table 1.

The mean number of primary teeth and the mean number of decayed primary teeth per person was 14.98 and 3.13 respectively. The percentage of subjects with caries in the primary dentition was 73%. Only 0.11% of total number of primary teeth examined was filled and the percentage of missing primary teeth per person was 2.54%.

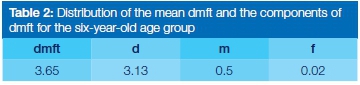

Table 2 shows a distribution of the components of dmft with low missing (0.5) and filled (0.02) components and a mean dmft of 3.65.

The severity of dental caries expressed as the mean dmft for schools and percentage dmft per child and district in KwaZulu-Natal are shown in Table 3.

The mean dmft scores for the districts ranged from a low of 1.9 (Umkhanyakude) to a high of 5.7 (Amajuba).

The d component of the dmft made up more than 85% of the total mean. The mean range dmft for schools was 1.1 (Mashesheleng, Umzinyati District) to 6.8 (Cebelihle, Amajuba District) which are both located in rural areas.

The percentage dmft per child ranged from a low of 4 (Mashesheleng Umzinyati District and Ezimbidleni Umkhanyakude District) to a high of 21 (Cebelihle, Amajuba District). This translated to 96% of the children having a dmft of 0 in the Umzinyati and Umkhanyakude districts, both rural areas. The percentage dmft per district ranged from a low of 6 (Umzinyati and Umkhanyakude) to a high of 18 (Amajuba). This meant that 94% of the children were caries free in the Umzinyati and Umkhanyakude districts, but only 82% in Amajuba.

Of the total sample only eight teeth had fillings recorded with seven from Bay Primary in the Uthungulu district. Seven fillings were present in one child. There were a higher number of posterior lower teeth missing due to caries compared with upper teeth.

The number of carious primary teeth by school and district in KwaZulu-Natal are shown in Table 4.

The percentage of decayed teeth varied widely for schools and districts with scores of 6 to 33.7 and 8.7 to 27.5 respectively. Umkhanyakude district, which had the lowest scores and Amajuba the highest are both rural areas.

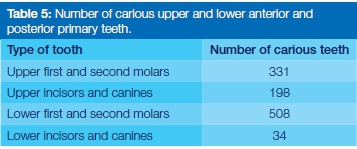

The number of carious upper and lower primary anterior (incisors and canines) and posterior (first and second molars) primary teeth for the study sample are illustrated in Table 5.

The lower molar teeth suffered a higher incidence of caries present compared with the upper molars (508 vs 331).

The findings for the anterior teeth were the opposite with a higher number of carious lesions present in the upper teeth. Higher caries scores were found predominantly in the rural areas.

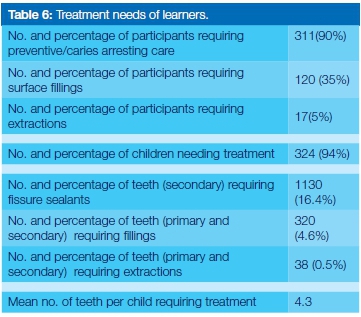

Table 6 shows the treatment needs of learners.

From the total sample (n=345), 94% (324) of the learners required some form of treatment. Ninety percent (90%) of the learners required preventive care, 35%, surface fillings and 5%, extractions. Learners at Sisonke, Ethekweni and Ugu districts required more fillings compared with learners in the Umgungundlovu and Ilembe districts.

The mean number of teeth requiring treatment per child was 4.3. Fissure sealants were required on 16.4% of the secondary (first permanent molar) teeth examined; while 4.6% and 0.5% (primary and secondary) teeth required fillings and extractions respectively.

DISCUSSION

The current data may not be a good indicator of the impact of caries in South Africa.12 A small number of epidemiological studies have been conducted in KwaZulu-Natal, especially in the rural areas.7 This has resulted in limited information on dental caries status being available to inform planned oral health interventions that is based on the needs of the population. There have been few or no studies which have considered etiological factors, parental education and social factors that include various population groups and social classes.612-15 Similar findings have been found in studies done elsewhere in Africa where various diagnostic methods were used and there was a variation in the age groups assessed.16

Of significance in dental caries epidemiological studies are the methods used for population sampling.15 South Africa has a diverse population with various social groups as well as populations living in different geographic locations namely urban, peri-urban and rural areas. It is therefore imperative that consideration be given to geographic distribution and to the methods used for population sampling prior to the planning of intervention strategies for dental caries.17 These data would inform policy planning and service delivery so that policies are tailored to meet the oral health needs of the various communities especially at district level.6,13

This study therefore drew a sample which included all eleven districts of KwaZulu-Natal. Any programmes to be implemented in response to the oral health needs of six-year-olds in the Province should then be informed by the data collected, which could be used as a baseline for other studies.

It is recognised that the permanent teeth were present for only a short period of time in the age group examined and were therefore were not exposed to caries risk factors for any length of time.

The results from this study were compared with the KwaZulu-Natal results from the two National Oral Surveys conducted in South Africa as shown in Table 7.

The Unmet Treatment Need Index (UTN)) was used to calculate the amount of oral health services needed to be provided for treatment of caries in the six-year-old age group. The UTN was 97% which translates to more than 90% of all caries in this group remaining untreated in KwaZulu-Natal. Comparison of the results obtained in the Durban area to the National Oral Health Surveys (Table 7) showed an increase in the decayed (d) component and a decrease in the filling (f) component. The increase in the d component could be as a result of a change in diet in this area. The decrease in f component could be as a result of extractions being the only option offered at primary health care centres.18

Results from this study showed an increase in prevalence of caries for six-year-olds in KwaZulu-Natal when compared with the results obtained in the last National Oral Health Survey (2003) (Table 7). Evidence also shows only that one district (Umkhanyakude) from the eleven districts had a low dmft score (1.9) (Table 3) indicating that dental caries has not been adequately addressed and that there remains a need for an improvement of oral health services in KwaZulu-Natal. When the data was further analysed it was clear that there was an increase in the d and m components and a decrease in the f component of the dmft with the latter indicating a possible decrease in the provision of restorative procedures in oral health services. The literature states that in KwaZulu-Natal the focus is currently on curative (extractions) rather than preventive services with a priority not given to oral health in budget allocations.718 With the increase in decayed and missing teeth it becomes imperative that children and mothers be targeted for preventive services so that parents and children understand the carious process and how to implement simple procedures for its prevention.

Results from this study have further identified that the percentages of caries amongst the rural sample varied considerably when compared with the experiences in the urban and peri-urban areas. There were also wide differences in the mean dmft per school and in the percentage dmft per child and per district for primary teeth. Although schools from the urban areas had high dmft scores (4.4; 4.9), they were not as high as in some of the rural areas (5.7) (Table 3). These results differed from studies done in other provinces in South Africa where rural scores were all lower than those in urban and peri-urban areas.19-20 A study conducted in Portugal showed the opposite trend with caries scores significantly higher in rural areas.21 The higher scores in the rural areas in the current study could be due to incorrect diet, source of water and fluoride content, lack of knowledge on oral health education, poor access to oral health care, and affordability of fluoridated toothpaste.22 More research should be done to establish the risk factors for caries and the reasons for the swings in high and low scores in rural areas.

Primary teeth in the rural and urban areas were found to have no restorations but there was evidence of a minimal amount of conservative work on children in the peri-urban areas with the majority from a school in the Uthungulu district. Similar results were obtained in a study undertaken in Venda.19 Overall it appears that scant curative services are delivered. This could be as a result of a scarcity of oral health personnel, limited resources, lack of accessibility to facilities and affordability. Priority needs to be given to six-year-olds for curative and preventive services.

Most relevant was the confirmation that the percentage of learners requiring treatment was very high (94%) (Table 5). The most common type of care needed was preventive services (fissure sealants). The need for prevention and restorations was higher than the need for extractions. This could be as a result of the criteria used where teeth that were decayed with no pain and could not be restored were nevertheless not indicated for extraction. Reasons for these high scores could include affordability and a lack of availability and accessibility to oral health services, especially in rural areas. The type of services required varied between districts. All districts required preventive services. The majority of restorations required came from the Sisonke, eThekweni and Ugu districts. For these services to be provided relevant oral health personnel, facilities, equipment and materials would have to be accessible.

Only 27% of the sample six-year-old age group in KwaZulu-Natal are caries free. More than 90% of caries goes untreated. If the criteria for the new National Health Goals for 2020, which state that 60% of 6-year-olds must be caries free and have fissure sealants placed on their first molars in Grade 1 are to be met in KwaZulu-Natal, oral health services would need to be drastically improved.4 In order for this to occur, School Health Services would need to prioritise oral health services by employing oral health personnel such as oral hygienists and dental therapists and ensuring that the focus of services provided at clinics should include restorative care for the treatment of caries.

Results from a previous study conducted in Hlabisa in 2002 were also compared with results from the Umkhanyakude district in this study, to which Hlabisa belongs.23 The dmft for the Umkhanyakude district was 6 in this study, which was double the score for Hlabisa (3). The increase in dmft could be as a result of an increase in per capita sugar consumption together with a decrease in water fluoride levels.24 There was a slight difference in the number of fissure sealants required per learner in both studies but there was a huge difference in the number of learners requiring restorations. In this study only 8 learners required restorations compared with 95 in the Hlabisa study. This large difference could be due to the differing criteria used for caries diagnosis in the deciduous teeth.

This study has revealed a high caries prevalence in the six-year-old age group in KwaZulu-Natal highlighting the need for a change in approach to the control of this disease. Taking into consideration the difference in availability of oral health services in the various districts and the fact that it will take a long time for this issue to be addressed due to limited funding, the school setting could provide an affordable platform for oral health promotion programmes based on the needs of the community at a local level. Data provided in this study reflects what is currently in place in KwaZulu-Natal and can be used as a basis for future planning of preventive programmes targeting primary school children.

CONCLUSION

The number of caries-free six year old children in KwaZulu-Natal has declined further compared with ten years ago. Dental caries is still a major public health problem and most children require some type of treatment including preventive care. Current oral health services need to shift from a curative to a more preventive approach for an improvement in service delivery. An effective and efficient oral health promotion programme at schools, targeting both parents and young children will do much to instil simple but beneficial oral health behaviours at an early age. It will take a long time to bridge the gap currently present, but making available basic information to learners and parents for the prevention of caries would be a good start.

Acknowledgements

This research project was supported with Research Grants from: The University of KwaZulu-Natal The National Research Foundation

Thanks and appreciation also to Prof F van Wyk, and statisticians Mr P Naidoo and Mr D Singh for assistance with the data analysis.

ACRONYMS

BASCD: British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry

UTN: Unmet Treatment Need

References

1. Williams WN. Dental caries in 12 year old South African school children. Journal of Dental Research 1983; 64(4): 597. [ Links ]

2. Department of Health. In vanWyk PJ (ed) National Children's Oral Health Survey. South Africa 1999/2002. Pretoria: Government Printer, 2003. [ Links ]

3. Department of Health. In van Wyk PJ (ed) National Oral Health Survey South Africa 1988/89. Pretoria: Government Printer, 1994. [ Links ]

4. Departmentof Health.National Oral Health Strategy(Confidential draft for comment only). April 2010: 1-15. [ Links ]

5. Singh S. Dental caries rates in South Africa: Implications for oral health planning. South African Journal Epidemiol Infect. 2011; 26(4(Part II)): 259-61. [ Links ]

6. Department of Health. KwaZulu-Natal - Strategic Plan 2010-2014. 2010: 68-69. (accessed 26 May 2014). [ Links ]

7. Peterson PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: Continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century - the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 2003; 31(1): 3-24. [ Links ]

8. Cleaton-Jones P, Fatti P. Dental caries in children in South Africa and Swaziland: a systematic review 1919-2007. International Dental Journal 2009; 59: 363-8. [ Links ]

9. Johnson B, Lazarus S. Building Health Promoting and Inclusive Schools in South Africa. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community 2003; 25: 81-97. [ Links ]

10. Boye U, Pretty IA, Tickle M, Walsh T. Comparison of caries detection methods using varying numbers of intra-oral digital photographs with visual examination for epidemiology in children. BMC Oral Health 2013; 13(6). [ Links ]

11. World Health Organisation 1997. Oral Health Surveys - Basic Methods. 4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organisation. [ Links ]

12. Ayo-Yusuf OA, Ayo-Yusuf IJ, van Wyk PJ. Socio-economic inequities in dental caries experience of 12 year old South Africans: policy implications for prevention. SADJ 2007; 62(1): 6-11. [ Links ]

13. Cleaton-Jones P, Chosack A, Hargreaves JA, Fatti P. Dental caries and social factors in 12-year old South African children. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 1994; 22: 25-9. [ Links ]

14. Gorden Y, Reddy J. Prevalence of dental caries, patterns of sugar consumption and oral hygiene practices in infancy in South Africa. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 1995; 13: 310-4. [ Links ]

15. Cleaton-Jones P, Richardson BD, Setzers S, Williams S. Primary dentition caries trends, 1976-1981, in four South African populations. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 1983; 11: 312-6. [ Links ]

16. Cleaton- Jones P, Fatti P. Dental caries trends in Africa. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 1999; 27: 316-20. [ Links ]

17. Lalloo R, Myburg NG, Hobdell MH. Dental caries, socio-economic development and national oral health policies. International Dental Journal 1999; 49: 196-202. [ Links ]

18. Singh S, Myburg NG, Lalloo R. Policy analysis of oral health promotion in South Africa. Global Health Promotion 2010; 17(1): 16-24. [ Links ]

19. Bajomo AS, Rudolph MJ, Ogunbodede EO. Dental caries in six, 12 and 15 year old Venda children in South Africa. East African Medical Journal 2004; 81(5): 236-43. [ Links ]

20. Cleaton-Jones P, Richardson BD, Winter GB, Sinwel RE, Rantsho JM, Jodaiken A. Dental caries and sucrose intake in five South African preschool groups. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1984; 12: 381-5. [ Links ]

21. de Almeida CM, Peterson PE, Andre SJ, Toscano A. Changing oral health status of six- and 12- year-old schoolchildren in Portugal. Community Dental Health 2003; 20: 211-6. [ Links ]

22. van Wyk PJ, van Wyk C. Oral health in South Africa. International Dental Journal 2004; 54: 373-7. [ Links ]

23. Brindle R, Wilkinson D, Harrison A, Connolly C. Oral health in Hlabisa, KwaZulu-Natal - a rural school and community based survey. International Dental Journal 2000; 50: 13-20. [ Links ]

24. Postma TC, Ayo-Yusuf OA, van Wyk PJ. Socio-demographic correlates of early childhood caries prevalence and severity in a developing country - South Africa. International Dental Journal 2008; 58(2): 91-7. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

M Reddy

Lecturer, Discipline of Dentistry, School of Health Sciences

University of KwaZulu-Natal-Westville Campus

Private Bag 54001 Durban 4000

Tel: 031 260 8270

E-mail: reddym@ukzn.ac.za