Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.70 no.7 Johannesburg 2015

RESEARCH

Assessment of an audit-feedback instrument for oral health care facilities in South Africa

J Oosthuysen; A Fossey

Central University of Technology, Free State, Department of Life Sciences, Bloemfontein, South Africa

SUMMARY

The assessment of an audit-feedback instrument (AFI) for infection prevention and control was conducted on a population of South African oral health care facilities, mainly to test its workability in the varied facility configurations. A purposive selection strategy was followed, selecting 50 South African oral health care facilities. Results from 49 completed AFIs revealed demographic details and information on infection prevention and control practices for the 11 AFI focus areas: Administrative controls; personnel protection controls; environmental- and work controls; surface contamination management; equipment maintenance; air- and waterline management; personal protective equipment usage; personal- and hand hygiene practices; sterilisation practices; sharps handling and waste management. None of the participating facilities demonstrated 100% compliance. Notably, administrative controls and air- and waterline management scored the lowest mean values; 31% and 36% respectively, while personal- and hand hygiene practices and waste management performed the best, at respectively 75% and 63%. The general lack of compliance with infection prevention and control precautions in the participating oral health care facilities clearly poses a safety hazard to patients and oral health care workers. These findings demonstrate the urgent need for a monitoring system, such as the AFI, to be instituted in South African oral health care facilities.

Keywords: Audit; dental; oral health care; compliance with infection prevention and control precautions

INTRODUCTION

In 1993, Marianos recommended that, in the absence of formal recommendations and guidelines for infection prevention and control precautions, South African dental practitioners should adhere to the infection control guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the United States of America.1,2 However, many health care facilities in South Africa lacked even the most basic infection control requirements, such as water and electricity,3 as a result compromising adherence to any form of international recommendation or guideline. In 2005, the Nelson Mandela Foundation Report confirmed that infection control practices in oral health care facilities were inadequate.4 Visible and invisible blood had been detected in oral health care environments and on "clean" instruments, signifying a collapse in basic infection prevention and control precautions in the country.5

In South Africa there are no policies, regulations or guidelines that sufficiently address infection prevention and control in oral health care. The National Infection Prevention and Control Policy and Strategy sets minimum national guidelines that do not specifically address the oral health care environment.6 The Norms, Standards and Practice Guidelines for Primary Oral Health Care comprises of a few pages briefly addressing infection prevention and control in primary oral health care facilities.7 This document is without detailed instructions covering the variety of oral health care procedures; diversity of training levels for oral health care personnel; or the availability of resources in rural and urban facilities, including public and private oral health care facilities. In particular, no mechanisms or auditing procedures to measure compliance with infection prevention and control guidelines are available in South Africa.

The development of an infection prevention and control audit-feedback instrument (AFI) and the ultimate practical application thereof for the health care providers, will contribute to a safer environment in oral health care facilities, taking into account the unique South African conditions; high incidence of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), Hepatitis B and C infection, tuberculosis infection and a violent society leading to trauma with open wounds as a regular feature in many patients.8-12 Thus, the purpose of an AFI is to provide a practical tool that can be applied by a variety of oral health care workers in oral health care facilities to ensure safe practice. Such an AFI was developed for oral health facilities in South Africa. This tool is a user-friendly, self administered, electronic tool that provides feedback to managers, and an opportunity for education and improvement in oral health care facilities. Besides providing instructions of how to use the AFI, provision is made for demographic details. This is followed by scoring tables which include 11 focus areas organised according to the logical order of the CDC guidelines on infection prevention and control in dentistry.1

These focus areas are:

Focus area 1: Administrative Controls

Focus area 2: Personnel Protection Controls

Focus area 3: Environmental- and Work Controls

Focus area 4: Surface Contamination Management

Focus area 5: Equipment Maintenance

Focus area 6: Air- and Waterline Management

Focus area 7: Personal Protective Equipment Usage

Focus area 8: Personal- and Hand Hygiene Practices

Focus area 9: Sterilisation Practices

Focus area 10: Safe Sharps Handling

Focus area 11: Waste Management

The aim of this study was to assess the AFI that was developed specifically for South African conditions. The assessment of the AFI was conducted on a population of oral health care facilities in South Africa, mainly to test its workability in the varied oral health care configurations and environments.

METHODS

A purposive selection strategy was followed, aimed at selecting 50 easily accessible South African oral health care facilities. This deliberate, non-random sample represented the different practice configurations found in South Africa. The strategy for sampling and data collection included the following:

• Representatives of oral health care facilities in rural and urban areas; including single practitioner-, multi-practitioner oral health care facilities; private dental clinics and governmental dental clinics; as well as exemplars of oral health care training institutions were included in the study.

• The number of each type of oral health care facility included depended upon the availability, accessibility, resources and time available. Therefore, the selected facilities represented a convenience sample.

• Once the oral health care facilities had been identified, appropriate permissions were obtained from managers and gatekeepers. Initial contact was made telephonically, after which an appointment was scheduled for the completion of the AFI.

• The completion of the AFI followed a structured and facilitated face-to-face process. All responses were recorded by the researcher.

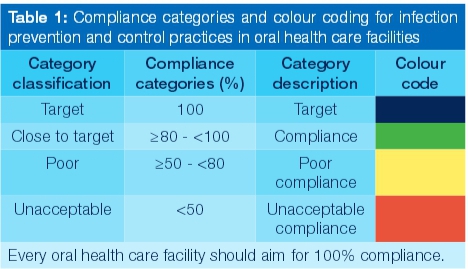

Summary statistics were calculated and the compliance with infection prevention and control measures were determined using four compliance categories (Table 1). These categories were developed from the colour categories applied for the assessment of drinking water safety in South Africa.13

RESULTS

Of the 50 selected oral health care facilities, 49 completed an AFI. Information was collected regarding the demographic details of each of the participating oral health care facilities, in addition to the data on infection prevention and control practices in the 11 focus areas.

Demographic details of the sample population

Main provider and practice details

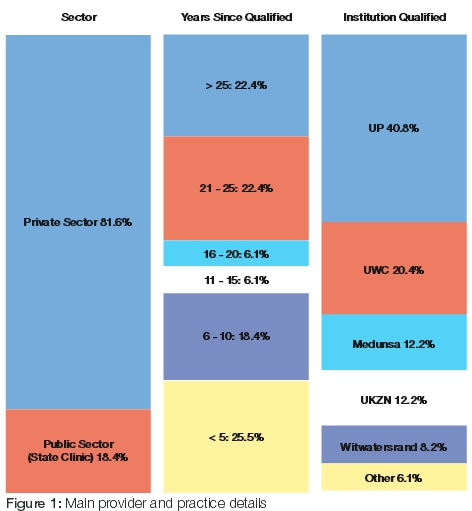

The majority of the oral health care facilities that participated and were assessed in this study were from the private sector. Most of the main service providers (dental practitioners and dental therapists) in each instance had been in practice for more than 20 years (44.8%) (Figure 1). The qualifications of the main service provider from each participating institution were representative of all five dental faculties in South Africa. Only a few had qualified outside of South African borders. On the other hand, approximately 25% of the main service providers were recently qualified, with less than five year's experience in clinical practice.

Audit respondent details

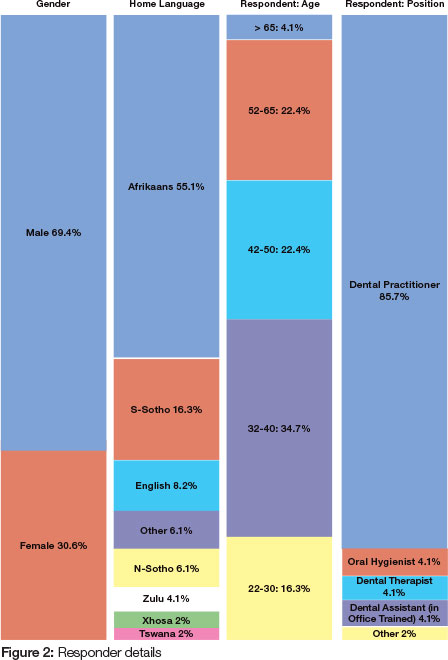

More than two-thirds of the respondents were male, representing eight of the 11 official South African languages, with Afrikaans being the most prevalent (Figure 2). The ages of the respondents were spread more or less evenly over the different age group categories, except for a number of respondents that were over the age of 65. Most of the research information was obtained from the dental practitioner, while in a few of the oral health care facilities, other members of the oral health care team assisted with the completion of the AFI.

Audit results

Audit results of individual participating facilities

Overall audit performance varied greatly between the 11 focus areas, as well as among the participating facilities. Only seven of the participating facilities achieved Target (Blue) in one or more focus areas (Table 2). More than half of the facilities exhibited Poor (Yellow) and Unacceptable (Red) compliance for most of the focus areas. One facility (ID #1) reached Target (Blue) in four focus areas, demonstrating the highest mean percentage of 80.8% (close to target). However, the performance of this facility in the focus areas Administrative controls and Personnel protection controls was categorised as Unacceptable (Red). Of all the 49 participating facilities, facility ID #1 was the only facility with a reasonable overall performance reaching close to Target. The overall performance of the remainder of the facilities was categorised as Poor (47%) or Unacceptable (51%).

Audit results of focus areas

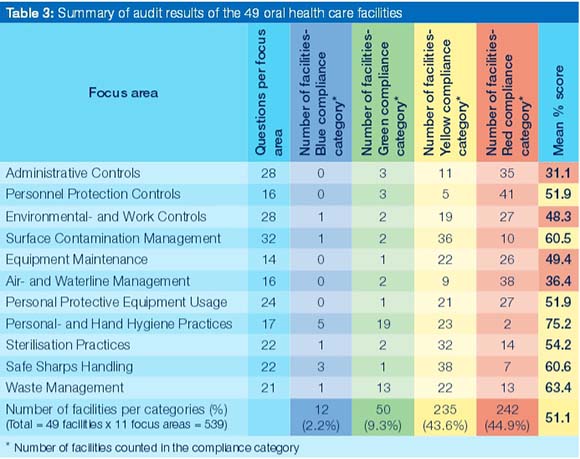

The overall mean performance on the 11 focus areas was calculated and categorised according to the different compliance categories. The focus area, Personal- and hand hygiene practices outperformed all the other focus areas, but still scored Poor compliance (Table 3). Similarly, with a lesser score on this result, the compliance of Waste management, Safe sharps handling, Surface contamination management, Sterilisation practices, Personnel protection controls, and PPE usage were also Poor. The most neglected focus areas in this study were Administrative controls and Air- waterlines management, followed by two focus areas, Environmental- and work controls and Equipment maintenance. The overall mean score of all facilities over all focus areas was just greater than 50%.

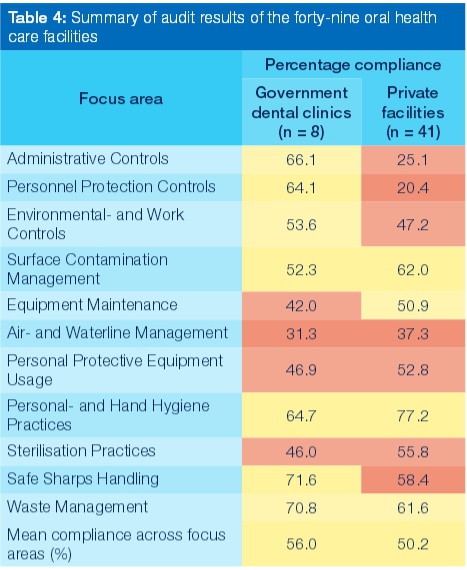

A comparison was made of the compliance performance between participating government clinics (public sector) and private oral health care facilities (private sector) to gain insight into the overall attention paid to infection prevention and control in these two types of facility. Although only a limited number of government clinics participated in the study, their overall performance revealed better compliance than that of the private sector (Table 4). The data further revealed that in government clinics, focus areas Administrative controls and Personnel protection controls, the government clinics outperformed the private sector by more than 40%. Both sectors paid reasonable attention to Personal- and hand hygiene practices and Waste management. Notable is the relatively high compliance rate obtained for Safe sharps handling in government clinics.

Comparison of audit results with target

To provide a more visual perspective of the results obtained in this study, a horizontal bar graph has been drawn. This graph demonstrates the overall range of compliance of the participating facilities to the Target expectation of 100% (Figure 3). The data collected in this study reveals that the mainly clinical focus areas of the participating facilities appeared to fall within the better compliancy categories, while the less clinical focus areas lie in the less compliant categories. A spider plot was constructed to create a pictorial overview of the compliance performance of the participating facilities in the different focus areas (Figure 4). The relatively small size of the central red outlined shape highlights the lack of compliance across all focus areas, when compared with the target of 100% (outer blue circle). The spider plot highlights the alarmingly low compliance of Administrative controls personnel, Protection controls and Air- / waterline management.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this research highlight the many shortcomings on a national level, and emphasise the need to improve compliance with infection prevention and control in all South African oral health care facilities. Although some measures of infection prevention and control precautions are executed in all oral health care facilities, the fact remains that unless these precautions are properly, fully and constantly applied, with the same set standard for each potentially exposing clinical procedure, the very purpose of the system will never be met.14,15

The study has revealed that the newly developed AFI could be applied to the wide variety of different configurations of oral health care facilities in South Africa. Contrary to the use of scientific and highly technical language found in other international audit instruments,16-18 the simple, understandable language and ease of interpretation was reported as an advantage by the participating facility managers, employers and the other members of oral health care teams who completed the AFI.

This AFI provided information covering the overall compliance of a facility, as well as the individual compliance of each of the 11 focus areas. These represent the range of areas presently in compliance with international infection prevention and control precautions in oral health care facilities. This comprehensive analysis of compliance performance enables individual facilities to identify areas of concern and shortcomings in their own workplace, and should thus enable them to implement remedial or improvement action.

The overall compliance of facilities was low, falling mostly into the categories of Poor or Unacceptable compliance, supporting the earlier research findings in South Africa.19-25 It may be relevant to note that the overall compliance performance of the public sector was greater than that in the private sector. This could be due to the fact that the public sector is officially regulated by quality control and accreditation bodies such as the Council of Health Services Accreditation of South Africa (COHSASA), while the public sector presently still has a choice of whether to voluntarily seek COHSASA accreditation or not.

The AFI has also provided detailed information regarding the compliance performance of the individual in the 11 different focus areas in the checklist. It is not surprising that the focus area of Personal and hand hygiene demonstrated the highest compliance score, particularly in the light of quite extensive media coverage and promotional initiatives to take preventive measures against disease transmission and injury.26-29 Recently, the CDC indicated that double gloving during surgical procedures would be included in the newly proposed guidelines for 2015, highlighting the importance of more effective prevention of the risk of disease transmission and injury during these procedures.30 However, taking into account the overall results, only half of the participating facilities fell in the Close to target category on the single most important infection prevention and control procedure, namely Personal and hand hygiene. The more resource-dependent categories, for example Environmental- and work controls, Surface contamination management, Sterilisation practices, Safe sharps handling and Waste management fell into the Poor compliance category, with only three facilities compliant with Safe sharps handling, and one each under the other categories. For PPE usage, which includes the availability and use of essential personal barriers such as protective clothing, eyewear, masks and gloves to shield personnel and patients during oral health care procedures, all facilities except one fell in the Poor compliance or Unacceptable compliance categories. In developing countries, the availability of basic resources such as electricity and water are daily clinical challenges.3 This often supports the notion that the lack of resources in developing countries is used as reason for non compliance with protective precautions.31,32

At the core of any oral health care facility are its personnel. With the specific burden of prevalent disease in South Africa, it is therefore difficult to comprehend the lack of attention that is paid to focus area Personnel protection controls, in all the participating facilities, but particularly so in the private sector. Furthermore, attention to this focus area requires far less resources than many of the other focus areas.33,34

The overall poor general management in facilities is demonstrated by the exceptionally low score of the focus area Administrative controls, again more so in the private sector. This emphasises the lack of record keeping, including proof of the minimum legislative safety or health requirements of all kinds in participating oral health care facilities. This poor result is underscored by the fact that none of the participating facilities fully complied with Administrative controls or Personnel protection controls.

The general lack of compliance with infection prevention and control precautions by the participating oral health care facilities clearly poses a safety hazard to both the patients and the oral health care workers. This study thus demonstrates the urgent need for a monitoring system, such as the newly developed AFI, to be instituted in South African oral health care facilities.

Acknowledgement

A sincere thank you to Dr Elsa Potgieter, Chief Microbiologist Man-gaung Metropolitan Municipality, Bloemfontein South Africa, for her support, inspiration, valuable inputs and advice. We also thank Sr Laura Ziady, Nurse Educator / IPC Assessor from Mediclinic South Africa, who assisted with language editing.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding sources

This investigation was partially financed by the National Research Foundation, South Africa, the Central University of Technology, Free State and the Dentistry Development Foundation of the South African Dental Association.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings - 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2003 19 December;52(Number RR-17):1-68. [ Links ]

2. Marianos, DW. Recommended infection control practices for dentistry ,1993: Practitioner's Corner. Journal of the Dental Association of South Africa. 1993;48(10):577-82. [ Links ]

3. Edward-Miller, J. Measuring quality of care in South African clinics and hospitals. South African Health Review. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 1998. p. Chapter 14. [ Links ]

4. McKay, E. Results of a research report into HIV risk exposure of young children (2-9) to HIV in the Free State province. Media release: Nelson Mandela Foundation2005 5 April 2005. [ Links ]

5. Shisana, O, Mehtar, S, Mosala, T, Zungu-Dirwayi, M, Rehle, T, Dana, P, Colvin, M, Parker, W, Connolly, C, Dunbar, R, Gxamza, F. HIV risk exposure in children: A study of 2-9 year-olds served by public health facilities in the Free State, South Africa. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council Press 2005. [ Links ]

6. The National Infection Prevention and Control Policy and Strategy, Department of Health, Republic of South Africa, 2007. [ Links ]

7. National Department of Health. Department of Health National norms, standards and practice guidelines for primary oral health care. South Africa: 24 June 2005. Directorate Oral Health. In: Health, DO, editor. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2005. [ Links ]

8. Sissolak, D, Marais, F, Mehtar, S. TB infection prevention and control experiences of South African nurses - a phenomenological study. Biomedcentral Public Health. 2011;11(262):1-10. [ Links ]

9. Shisana, O. High HIV/AIDS prevalence among health workers requires urgent action: Editorial. South African Medical Journal. 2007;97(2):108-9. [ Links ]

10. Jentsch, U. A review of opportunistic infections in Africa: current topics. South African Journal of Epidemiology and Infection. 1997;12:28-32. [ Links ]

11. Mayaphi, SH, Rossouw, TM, Masemola, DP, Olorunju, SAS, Mphahlele, MJ, Martin, DJ. HBV/HIV co-infection: The dynamics of HBV in South African patients with AIDS. South African Medical Journal. 2012;102(3):157-62. [ Links ]

12. Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. Department of Health Strategic Plan 2010/11-2012/13 South Africa. In: Department of Health, RoSA, Health Sector, editor. Pretoria 2010. [ Links ]

13. WRC, DWAF, DoH. Quality of domestic water supplies Volume 1: Assessment Guide. 2 ed. Pretoria: Water Research Commission, Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, and Department of Health South Africa; 1998. [ Links ]

14. Ziady, LE, Small, N. Prevent and control infection for safer healthcare practice. Second ed. Cape Town, South Africa: Juta and Co Ltd; 2013. [ Links ]

15. Mehtar, S. Lowbury Lecture 2007: infection prevention and control strategies for tuberculosis in developing countries and lessons learnt from Africa. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2008;69(4):321-7. [ Links ]

16. GRICG. GRICG infection control compliance audit: clinical units dental practice2013 [cited 2013 April]; 2013(7):1-13. Available from: http://www.google.co.za/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=20&cad=rja&ed=0CFgQFjAJOAo&url=http%3A%2F %2Fwww.grhc.org.au%2Fdocument-library%2Fdoc_download%2F375-gricg-dental-audit-april-2013-version-7&ei=i_7FUZ3WKYeL7AamzoHACw&usg=AFQjCNBTQfrRe3GlTrQyBeooW8BEP7sBQ&bvm=bv.48293060,d.ZGU. [ Links ]

17. Infection Prevention Society. Dental Audit Tool 2013 Edition. [Audit tool] England: IPS; 2013 [updated 22 June 2013; cited 2013 16 December]; Second:[Available from: http://www.ips.uk.net/DentalAuditTool/2013%20Question%20Set.pdf. [ Links ]

18. American Dental Association. The ADA Complete HIPAA Compliance Kit (J598). American Dental Association; 2013 [cited 2014 23 April]; Available from: http://catalog.ada.org/productcatalog/596/HIPAA/The-ADA-Complete-HIPAA-Compliance-Kit/J598. [ Links ]

19. Yengopal, V, Naidoo, S, Chikte, UM. Infection control among dentists in private practice in Durban. South African Dental Journal. 2001 Dec;56(12):580-4. [ Links ]

20. Oosthuysen, J. Infection control techniques used in South African dental practices. Thesis MTech: Biomedical Technology. Bloemfontein: Central University of Technology, Free State; 2003. [ Links ]

21. Nemutandani, MS, Yengopal, V, Rudolph, MJ, Tsotsi, NM. Occupational exposures among dental assistants in public health care facilities, Limpopo Province. South African Dental Journal. 2007 September 2007;62(8):348-55. [ Links ]

22. Nemutandani, MS. Occupational exposures among dental assistants in Limpopo dental clinics. Johannesburg: University of Witwatersrand 2008. [ Links ]

23. Oosthuysen, J, Potgieter, E, Blignaut, E. Compliance with infection control recommendations in South African dental practices: a review of studies published between 1990 and 2007. International Dental Journal. 2010 Article first published online: 8 APR 2011;60(3):181-9. [ Links ]

24. Chikte, UM, Khondowe, O, Gildenhuys, I. A case study of a dental receptionist diagnosed with Legionnaires' disease. South African Dental Journal. 2011;66(6):284-7. [ Links ]

25. Mehtar, S, Shisana, O, Mosala, T, Dunbar, R. Infection control practices in public dental care services: findings from one South African Province. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2007 April;66:65-70. [ Links ]

26. World Health Organization. World Health Organization Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Healthcare (Advanced Draft) - Global patient safety challenge 2005 - 2006: "Clean care is safer care". Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2006 [updated April 2007; cited 2007 21 August]; Available from: http://www.who.int/patientsafety. [ Links ]

27. World Health Organization. Guide to implementation: A guide to the implementation of the WHO multimodal hand hygiene improvement strategy. Save lives clean your hands. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2009 [cited 2012 3 August]; Available from: WHO_IER_PSP_2009.02_eng.pdf. [ Links ]

28. World Health Organization. The WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care 2009. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2009 [cited 2012 3 August]; Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241597906_eng.pdf. [ Links ]

29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2002 October;51(RR-16):1-85. [ Links ]

30. Fluent, MT, Pawloski, CL. CDC Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings: Looking Ahead to 2015. PennWell; 2014 [updated May 2014; cited 2014 25 May]; Available from: http://www.ineedce.com/coursereview.aspx?url=2592%2FPDF%2F1405cei_Fluent_web.pdf&scid=15327. [ Links ]

31. Rimkuvienë, J, Pürienë, A, Peèiulienë, V, Zaleckas, L. Use of personal protective equipment among Lithuanian dentists. Sveikatos Mokslai. 2011;21(2):29-36. [ Links ]

32. Puttaiah, R, Shetty, S, Bedi, R, Verma, M. Dental infection control in India at the turn of the century. World Journal of Dentistry. 2010;1(1):1-6. [ Links ]

33. Marie, RJ. The cost of infection control and OSHA compliance within dental group practice. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses: Walden University; 1994. [ Links ]

34. Slater, F. Cost-effective infection control success story: A case presentation. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2001;7(2):293-4. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

J Oosthuysen

Central University of Technology

Free State, Department of Life Sciences

Private Bag X20539

Bloemfontein 9300, South Africa

Tel: +27 51 507 3388

Fax: +27 86 545 9616

E-mail: jeanneo@cut.ac.za