Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.70 no.3 Johannesburg Abr. 2015

CLINICAL COMMUNICATION

Who visits a periodontist and why?

A VolchanskyI; S PrinslooII

IBDS (Durham) PhD (Wits). Department of Oral Medicine and Periodontology, School of Oral Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

IICert in Chairside Assisting (Tshwane), Private Practice, Johannesburg

OBJECTIVE

To record the broad demographics of patients attending a private periodontal/oral medicine practice. The purpose of this study was to establish the age and gender distribution of these patients and to compare these findings with a similar study carried out in 1977. In addition to the age and gender, the reasons and/or the complaints of the patients were recorded. This is a retrospective review of patient records.

INTRODUCTION

In our previous study it was found that nearly half (47%) of the patients attending the practice sought consultation only. Included amongst these were patients attending for consultation for an oral medicine diagnosis, those who were referred back to the general practitioner for treatment, those who declined treatment, as well as those who did not keep a further appointment.1

Papapanou in a recent review article asks the questions: "what are the levels of disease in the populations and what are the determinants of its extent and severity?"2

It is well known that the periodontal diseases are widespread throughout the world populations3 and that the afflictions are linked to many systemic conditions.4 These are some of the motives why we looked at patient attendance at a periodontal practice and the reasons for their visits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

One thousand two hundred and sixty two patient record cards were examined in sequential order and the following information noted:

1. Age and gender of the patient.

2. The main complaint or reason for the consultation.

3. Whether the patient had either a periodontal or oral medicine problem.

4. Source of the referral, for example a Dental practitioner, Medical Aid, Internet or personal referral.

5. Whether consultation alone was sought or whether treatment was undertaken.

A periodontal problem was defined as either gingivitis or periodontitis. No further subdivisions were recorded. Oral medicine problems included lesions of the oral cavity such as white lesions, ulcers, conditions of the tongue, the lips and non-keratinized oral mucosa. Temporo-mandibular joint dysfunction was not included in the study.

A consultation was defined as one or two visits, the second visit being a follow-up consultation. Treatment was considered as requiring a minimum of three visits.

Statistical analysis was with Chi square test using Instat (version 3.1, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) at six degrees of freedom. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

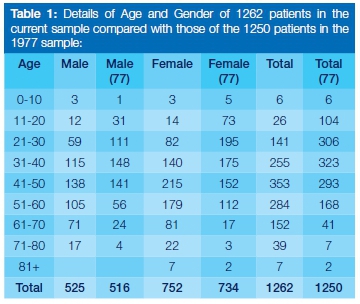

Of the 1262 patients seen, 520 were male and 742 female, a male to female ratio of 1:1.4. Their ages ranged from 10 to 80+ and are listed in decades in Table 1. The mode and median in the current study was the 41-50 decade compared with 31-40 in the 1977 sample. The difference in age decades between the samples is statistically highly significant (p<0.0001, Chi square = 235.76). The same mode and median pattern is present within males and females in each of the samples. In the current sample there is no statistically significant difference in age decades. When sexes are compared between the samples, males in the 1997 sample are significantly younger than males in the current sample (p<0.0001, Chi square = 72.43). Females are also significantly younger in the 1977 sample (p<0.0001, Chi square = 174.08).

One thousand two hundred patients presented with a periodontal problem, while 62 were specifically oral medicine patients, of whom there were 39 females and 23 males.

Considering the patient's complaint and/or the reason for the initial consultation, the following were the main concerns of the presenting patients, and the frequencies in which each occurred:

- Referred for periodontal treatment, or the patient stating "I require periodontal care", but with no specific complaint: 357

- Pain and or discomfort: 266

- Gum recession: 116

- Tooth mobility, loose teeth: 113

- Other, which included, for example, splaying of teeth, bad breath and bad taste: 103

- Bleeding gums: 95

- Abscesses: 89

- Specific Oral Medicine: 62

- Surgical: 61

Three hundred and seventy seven of the periodontal patients sought consultation only. Of the sixty two oral medicine patients, 29 (47%) sought consultation only. Two hundred and eighty five patients had not been referred by dentists. They comprised direct patient referrals, as a result of direction by Medical Aids, after personal internet searches and by medical staff at the local hospital.

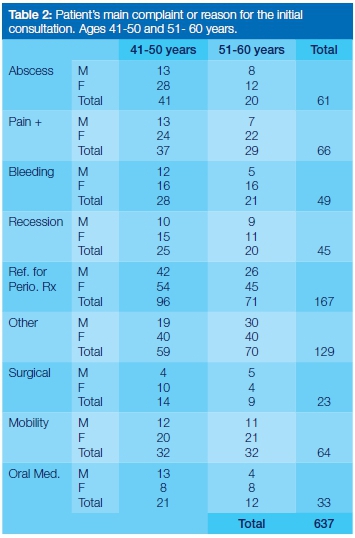

Six hundred and thirty seven (slightly more than half) of the patients were in the age range 41-60 years. Table 2 reflects a study of their main complaint and / or their reason for the initial consultation, recognizing that this constituted the majority of the patients attending the practice.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the severity of disease and finite treatment have not been investigated. The reasons for the patient attendance may be instructive. Referral by a dental colleague appears to be the most frequent reason, combined with the patient stating "I require periodontal care". This is in contrast with the finding of Brunsvold et al (1999)5 who found the chief reason to be "I was told I have gum disease" That study reported that the third most common complaint was "bleeding gums" In the current investigation the complaints ranged from pain and or discomfort and then tooth mobility and gum recession, Of almost equal frequency were bad taste, bad breath, splaying of teeth, and then bleeding gums.

The change in the age distribution of the samples with patients now attending the practice at an older age may simply be an incidental finding, although one is tempted to claim an enhanced dental awareness as a major influence in preventing the onset of oral disease until later in life. It is clear however that the need for periodontal care is as necessary as ever and in this regard, the following questions, with regard to "time and periodontal needs" in South Africa, may be posed:

- "How much time is devoted to periodontal care in the undergraduate dental and oral hygiene curricula, and is that adequate to cover the needs of a general dental practitioner?"

- "What percentage of time in a general dental practice is devoted specifically to periodontal / oral medicine care?"

- "What percentage of the South African population require periodontal care?"

- "Has there been a recent study on the dental / periodontal needs in a South African population?"

In this observational study, one was not able to determine the intensity of the practice. Could more patients have been seen and cared for? What one can determine from the study is that the age range of patients attending the practice were older, particularly from forty to seventy years.

CONCLUSIONS

In the 1977 study the highest number of patients was in the 31-40 age group, compared with the present study where it is the 41-50 age group. This apparent shift may be due to enhanced preventive measures being practised by younger patients, or could be the result of more general practitioners managing the early stages of periodontal disease. By far the greatest number of patients attending the practice had been referred for periodontal treatment, confirming the prevalence of the condition.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Professor P Cleaton-Jones for his advice and assistance, notably with statistical presentation, and Professor W G Evans for his guidance.

References

1. Volchansky A, Loudon L, Flores S. Who visits a periodontist? J South African Dental Assoc. 1977 ; 32:599-600. [ Links ]

2. Papapanou PN. Advances in periodontal disease epidemiology: a retrospective commentary. J Periodontol. 2014 ; 85:877-9. [ Links ]

3. Papapanou PN, Linde J. Epidemiology of periodontal diseases. In: Linde J, Lang N P, Karring T. eds. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. 5th Ed. Blackwell, Munksgaard, 2008. [ Links ]

4. Mealey BL, Klokkefold PR. Impact of periodontal infection on systemic health. In: Newman MG, Tekei HH, Klokkefold PR, Carranza FA. eds. Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. 11th ed. Elsevier, St Louis, 2012. [ Links ]

5. Brunsvold MA, Nair P, Oates TW. Chief complaint of patient seeking treatment for periodontitis. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:359-64 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A Volchansky

Tel: 011 442-6243

E-mail: volchans@iafrica.com