Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562

Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.69 n.10 Johannesburg Nov. 2014

CASE BOOK

Oral medicine case book 65: Necrotising stomatitis

RAG KhammissaI; R CiyaII; Tl MunzheleleIII; M AltiniIV; Ε RikhotsoV; J LemmerVI; L Feller.VII

IBChD, PDD, MSc (Dent), MDent (PeOM). Department of Periodontology and Oral Medicine, University of Limpopo, Medunsa Campus, South Africa

IIBChD. Department of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, University of Limpopo, Medunsa Campus, South Africa

IIIBDS, PDD, MBChB, MChD, FCMFOS (SA). Department of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, University of Limpopo, Medunsa Campus, South Africa

IVBDS, MDent (OPath), FCPath (SA). Division of Anatomical Pathology, School of Pathology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VBDS, MDent (MFOS), FCMFOS (SA). Department of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VIBDS, HDipDent, FCD(SA)OMP, FCMSAae, Hon.FCMSA. Department of Periodontology and Oral Medicine, University of Limpopo, Medunsa Campus, South Africa

VIIDMD MDent (OMP). Department of Periodontology and Oral Medicine, University of Limpopo, Medunsa Campus, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Necrotising stomatitis is a fulminating anaerobic poly-bacterial infection affecting predominantly the oral mucosa of debilitated malnourished children or immunosuppressed HIV-seropositive subjects. It starts as necrotising gingivitis which progresses to necrotising periodontitis and subsequently to necrotising stomatitis. In order to prevent the progression of necrotising stomatitis to noma (cancrum oris), affected patients should be vigorously treated and may require admission to hospital. Healthcare personnel should therefore be familiar with the signs and symptoms of necrotising gingivitis/necrotising periodontitis, of their potential sequelae and of the need for immediate therapeutic intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Necrotising gingivitis is a mixed anaerobic bacterial infection characterised by marginal gingival necrosis, bleeding and pain (Figure 1).1 The term "necrotising gingivitis" should be used in preference to the term "necrotising ulcerative gingivitis" because in necrotising gingivitis ulceration is not a primary feature, but is in fact a manifestation of the necrosis.2 It usually starts at the tips of the interdental papillae, where the attenuated blood supply makes the papillae vulnerable to bacterial-induced ischaemic tissue necrosis.1,3 Untreated necrotising gingivitis may progress, extending into the marginal periodontal attachment apparatus, when it is called necrotising periodontitis. Necrotising gingivitis and necrotising periodontitis are collectively termed necrotising periodontal disease.4

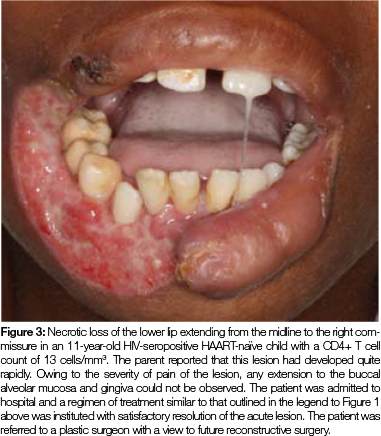

Necrotising periodontal disease may extend beyond the mucogingival junction to become necrotising stomatitis (Figure 1 and 2), which in a debilitated, malnourished or immunosuppressed host may rapidly spread centripetally with progressive destruction, ultimately resulting in the formation of a full thickness perforation of the mucosa, muscle and skin.3,5,6 This condition is called noma (cancrum oris) (Figure 3).

Necrotising gingivitis and early necrotising periodontitis respond favourably to systemic antibiotic therapy and frequent lavage with saline or preferably with a chlorhexidine mouthwash. Once the pain has been controlled by these measures, together with analgesics, then plaque control, scaling and if necessary root planing should follow.7,8 This simple treatment regimen will prevent the progression of necrotising periodontal disease to necrotising stomatitis, so early treatment is essential.5

Necrotising stomatitis is a polybacterial anaerobic infection frequently occuring in a host immunocompromised by systemic infection (i.e. HIV), by malnutrition, or by other states of debility.1 Severely debilitated patients with advanced necrotising stomatitis should be admitted to hospital for intravenous antibiotic treatment, fluid, electrolyte and nutritional supplementation and for daily irrigation of the necrotic intra-oral lesions with saline or with chlorhexidine solution, debridement, and removal of mobile teeth and necrotic bone (Figure 1),6-9

In an HIV-seropositive subject with necrotising gingivitis/ necrotising periodontitis/necrotising stomatitis, who is not receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), that regime should of course be started immediately, as any improvement in the immune status may help to contain the necrotising process.

DISCUSSION

While necrotising stomatitis is caused primarily by anaerobic bacteria including, but not limited to spirochaetes and fusiform bacilli, these micro-organisms can exist in the mouths of debilitated, malnourished or immunocompromised persons and even of healthy persons, without causing necrotising gingivitis/periodontitis/stomatitis. Clearly, therefore, other risk factors must also exist for necrotising stomatitis to develop.3 HIV-associated neutropenia, low CD4+ T cell count and cytokine dysregulation are some of the factors that may favour the anaerobic bacterial challenge.1,10

The anaerobic bacteria associated with the necrotising process are highly-proteolytic and tissue invasive.1 They release virulent agents that are cytopathic to periodontal cells and to local immuno-inflammatory cells, that degrade extracellular matrix proteins and that disrupt the local vasculature, ultimately causing direct tissue damage with associated haemorrhage.1,5 These bacterial agents also have the capacity to attenuate local immune responses, promoting tissue colonisation and invasion, and tissue destruction and in a debilitated vulnerable host, these effects culminate in a necrotic condition.1-3

Furthermore, in HIV-seropositive subjects, HIV-associated elevated levels of cytopathic viral and fungal species, by interacting synergistically with the complex of anaerobic bacteria, exaggerate the tissue necrosis.1,2

COMMENTS

- The natural progression from an initial anaerobic bacterial infection of the marginal gingiva to full-blown necrotising stomatitis is the result of dynamic interactions between virulent bacteria on the one hand and the host's general state of health, immune system, and local micro-enviromental factors, on the other hand.

- In the South African context nowadays, necrotising stomatitis occurs predominantly in HIV-seropositive persons. Further research is needed into the relationship between HIV infection and necrotising stomatitis, into the general prevalence of necrotising stomatitis and into factors that either, confer protection against, or promote the progression of necrotising periodontal disease to necrotising stomatitis. This may allow the formulation of evidence-based guidelines for the prevention of necrotising stomatitis.

- In summary, whether related to HIV, to malnutrition or to any other state of debility and in the presence of a fairly specific complex of anaerobic bacteria, diminished immunity appears to be the systemic common denominator in the pathogenesis of necrotising stomatitis.

References

1. Feller L, Lemmer J. Necrotizing periodontal diseases in HIV-seropositive subjects: pathogenic mechanisms. Journal of the International Academy of Periodontology 2008; 10: 10-5. [ Links ]

2. Feller L, Lemmer J. Necrotizing gingivitis as it relates to HIV infection: a review of the literature. Perio - Periodontal Practice Today 2005; 2: 285-91. [ Links ]

3. Feller L, Altini M, Chandran R, Khammissa RA, Masipa JN, Mohamed A, Lemmer J. (2013a). Noma (cancrum oris) in the South African context. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine 2014; 43 (1) : 1-6. [ Links ]

4. 1999 International Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions. Papers. Oak Brook, Illinois, October 30-November 2, 1999. Annals of Periodontology / The American Academy of Periodontology 4: i, 1-112. [ Links ]

5. Masipa JN, Baloyi AM, Khammissa RA, Altini M, Lemmer J. Feller L. Noma (cancrum oris): a report of a case in a young AIDS patient with a review of the pathogenesis. Head and Neck Pathology 2013; 7: 188-92. [ Links ]

6. van Niekerk C, Khammissa RA, Altini M, Lemmer J and Feller L. Noma and cervicofacial necrotizing fasciitis: clinicopathological differentiation and an illustrative case report of noma. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses 2014; 30: 213-6. [ Links ]

7. Shangase L, Feller L, Blignaut E. Necrotising ulcerative gingivitis/ periodontitis as indicators of HIV-infection. South African Dental Journal 2004; 59: 105-8. [ Links ]

8. Phiri R, Feller L, Blignaut E. The severity, extent and recurrence of necrotizing periodontal disease in relation to HIV status and CD4+ T cell count. Journal of the International Academy of Periodontology 2010; 12: 98-103. [ Links ]

9. Feller L, Khammissa R, Kramer B, Lemmer J. Oral squamous cell carcinoma in relation to field precancerisation: pathobiology. Cancer Cell International 2013b; 13: 31. [ Links ]

10. Feller L, Khammissa R, Wood N, Meyerov R, Pantanowitz L, Lemmer J. Oral ulcers and necrotizing gingivitis in relation to HIV-associated neutropenia: a review and an illustrative case. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses 2012 ; 28: 346-51. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

L Feller

Head: Dept. Periodontology and Oral Medicine

Box D26 School of Dentistry

MEDUNSA 0204

South Africa

Tel: (012) 521 4834

E-mail: liviu.feller@ul.ac.za