Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Dental Journal

versão On-line ISSN 0375-1562

versão impressa ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.69 no.8 Johannesburg 2014

RESEARCH

Oral health needs and barriers to accessing care among the elderly in Johannesburg

MP MoleteI; V YengopalII; J MoormanIII

IBDS, MSc, MDent. Specialist in Community Dentistry. University of the Witwatersrand, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Community Dentistry

IIBCHD, BSc, MDent. Professor/ Senior Specialist in Community Dentistry. University of the Witwatersrand, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Community Dentistry

IIIMBBS, MSc, FCPHM (SA). Senior Specialist in Public Health. University of the Witwatersrand, Faculty of Health Sciences,School of Public Health

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: The study sought to determine barriers to accessing oral health services amongst the elderly residing in retirement villages in Johannesburg. The objectives were to determine the normative and perceived oral health needs, the barriers experienced and the predictors of oral health utilisation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS: This was a cross-sectional study. Three hundred and eight (n=308) participants were recruited from 10 retirement villages in Johannesburg. Data were collected from questionnaires and clinical oral examinations assessing the DMFT and CPITN scores.

RESULTS: The clinical findings of the oral health status indicated a caries experience of 46%, whilst 58% of participants suffered from periodontal conditions. Sixty four percent (64%) acknowledged the need to visit a dentist, however only 28% of the study population had utilised oral health care in the past 12 months, due to perceived barriers. The barriers most frequently reported included the belief that they were not able to afford dental treatment and the lack of transport availability. The multivariate analysis indicated that a significant positive predictor of utilisation was Perceived Need.

CONCLUSION: Though oral health access was freely available in the public sector and normative and perceived need for oral health care were high, the barriers experienced prevented 72% of the participants from utilising oral health services.

ACRONYMS

DMFT: Decayed Missing and Filled Teeth score

CPITN: Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Need

INTRODUCTION

The elderly present with oral health problems that affect both their general health and oral health related quality of life.1,2,3 Oral health conditions may impact negatively on chewing performance, and can cause pain and embarrassment about the shape of the mouth due to missing, or discoloured teeth. In addition systemic diseases and the unfavourable effects of accompanying medications can lead to adverse oral health symptoms such as reduced salivary flow, altered senses of taste and smell, oro-facial pain, gingival overgrowth, alveolar bone resorption and tooth mobility,4 These factors ultimately affect dietary choices, self-esteem and general wellbeing.5,6 However, it has been shown that these oral health needs are often neglected and utilisation of oral health services amongst this population is low.5,7,18

A study determining the oral health utilisation amongst adults and older adults in Brazil indicated that utilisation was inversely proportional to age. Older adults, aged 60 and above, had a utilisation rate of 17,2% in comparison with those between the ages of 20-59 years at 32.7% (p<0.001).6 Dental access barriers contributing to the low utilisation have been reported widely and include advancing age, poor systemic health, high cost of dental treatment, long distances and waiting times, low perception of dental need and lack of social support.7,10,11,l2

The information available on dental health needs, health service utilisation and barriers experienced by the elderly in accessing care is relatively outdated in South Africa. The last dental survey was conducted in 1989.13 At that time 95% of the study population had periodontal conditions, the mean Decayed Missing and Filled Teeth score (DMFT) was 21, the rates of utilisation declined with advancing age and the most significant reported barriers to care were health-systems-related, such as long waiting times.

The health system in South Africa has undergone significant transformation since then and primary health care, including oral health services, are available at no cost for all citizens in the public sector14 The lack of current data on the oral health status, needs and possible barriers to care, limits planning of oral health programs for the elderly.

The aim of the study was to investigate barriers to accessing oral health care amongst an elderly sample residing in government-subsidized retirement villages, The objectives were to determine the normative and perceived oral health needs, the barriers experienced in accessing care and to define the predictors of oral health utilisation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in retirement villages in six district regions in Johannesburg, The retirement villages are managed by the local government and cater for the functionally independent elderly. Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand (M111009), Participants over the age of 60 without mental disorders affecting communication and memory function were recruited, The information provided by the management of the retirement villages indicated that the population size was 1511, Taking the size of the population into account and considering an expected frequency of dental utilisation rate at 35%10 with the worst acceptable rate of 30%12, a minimal sample size of 284 was required for a 95% confidence interval (Epi-Info, version 3,5,3).

A stratified sampling technique was applied, identifying the regions as strata, The number of elderly required in each stratum was proportional to the population, All individuals in each stratum who fulfilled the study criteria were invited to participate.

An interviewer-administered questionnaire was adapted from a validated questionnaire developed by the Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa for the National Oral Health Survey15 The questionnaire collected data on demographic information, utilisation of services and perceived barriers to care and perceived needs, The questionnaire was pilot tested on 10 participants who were selected from a retirement village that was not included in the study. All the findings from the pilot study were used to modify the draft questionnaire for the main study.

The normative oral health status was measured by using the DMFT index and the Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Need (CPITN), The unmet treatment need proportion was calculated by dividing the D component by the DMFT16 Participants were examined in a mobile dental unit following a procedure according to the World Health Organization Oral Health Survey Methods17 In terms of perceived need, participants were asked whether they believed there was anything wrong with their teeth, gums or tongue, The responses were dichotomized as a No or a Yes, Those who responded with a Yes to any of the categories of teeth, gums and tongue were coded positive for perceived need, The data was entered into Epi-info version 5,35 and analyzed in STATA 10, The Chi-squared and Logistic regression tests were undertaken and statistical significance was set at p<0,05.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

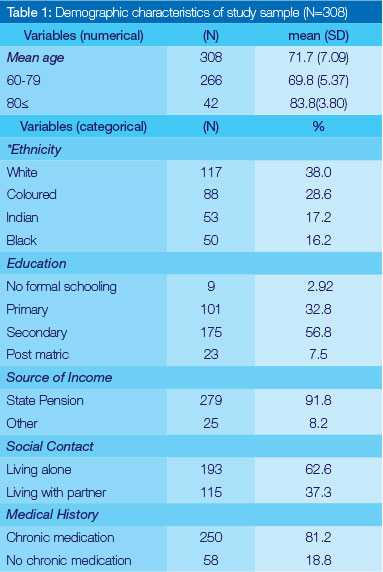

More than 284 individuals agreed to participate in the study and the final sample size consisted of 308 participants, The mean age of the population was 72 years old, almost two thirds (65,2%) were females and the highest educational attainment was secondary schooling, All other background characteristics are illustrated in Table 1.

Normative oral health needs

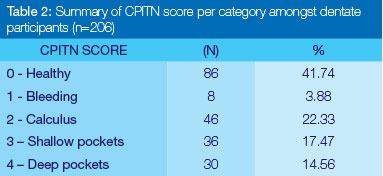

Thirty three percent of participants were edentulous and 66,8 % were dentate, The mean DMFT was 17,56 (SD: 11,67), with a caries experience of 46,1% among those with a DMFT above zero, and an unmet treatment need of 9,6%, In terms of the CPITN, 58% of participants had a CPITN of more than zero (Table 2).

Perceived oral health needs

Amongst the 308 participants, 64.3% (n=198) felt that their oral health needed to be attended to.

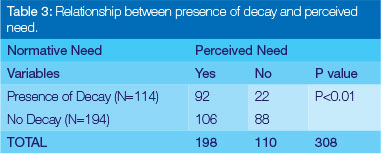

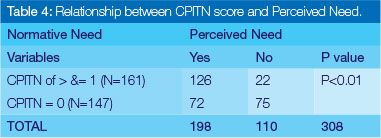

When the normative needs as captured by the oral health examinations were compared with perceived needs as reported by participants, the data indicated that of the (n=198) individuals that responded positively to perceived need, participants without decay had a significantly (p<0.01) higher perception of need than those with decay (Table 3). However, participants who presented with a CPITN of 1 to 4 had a significantly (p<0.01) higher perception of need than those with a zero CPITN score (Table 4).

Utilisation

Less than a third (n= 85: 27,6%) of the study population had utilised oral health services in the past 12 months.

Barriers

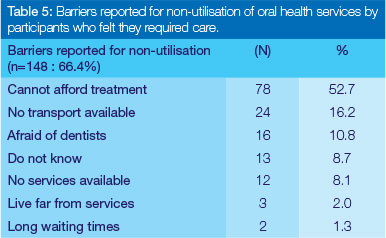

Amongst the participants (n=223: 72.4%) who had not utilised any oral health services, 33.6% felt that they did not require a dentist and hence did not report on any barriers. Therefore (n=148: 66.4%) reported on the barriers indicated in Table 5. The most common barriers reported were the inability to afford dental treatment (n=78: 52.7%) followed by the lack of transport (n=24: 16.2%).

Predictors of utilisation

Variables which indicated a statistical significance at p< 0.05 in the Chi-squared tests were included in the logistic regression analysis. Participants of the age of 80 and above were less likely (OR: 0.39; CI: 0.15-0.97; p=0.04) to utilise oral health services. Those who perceived the need for oral care were more likely (OR: 2.02; CI: 1.15-3.54; p=0.01) to utilise oral health services. Participants who had indicated that they were generally satisfied with their mouths were less likely (OR: 0.51; CI: 0.29-0.87; p=0.01) to utilise oral health services. When the multivariate analysis was undertaken and odds ratios were adjusted, the relationship between age and utilisation increased in significance, from (p=0.04 to 0.02). Those living with partners were less likely (OR: 0,43; CI; 0,19-1,00; p=0,05) to utilise the services, Those who perceived the need for oral care were more likely (OR: 2,37; CI: 1,00-5,83; p=0,05 ) to seek oral health attention (Table 6), There was no significant association between systemic health, long distances to clinics, waiting times and utilisation.

DISCUSSION

The study indicated that despite there being free oral health services available, normative oral health needs were identified yet utilisation of the oral health services was low. Though perceived oral care need was generally high amongst all participants, this felt need did not necessarily translate to an expressed need that would ultimately result in the utilisation of oral health services, The barriers attributed to the low utilisation rate of 28% included the belief that oral health care costs were unaffordable and that there was inadequate transport available, In addition, predictors of utilisation were found to be significantly influenced by age, living with a partner and perceived need.

Participants in the study resided in government funded retirement villages which generally accommodate the elderly from a low socio-economic grouping and only 8% of the participants had access to private pension, The socio-demographic profile is representative of that of the general elderly population in South Africa in that most of the adults over 64 years are poor, not economically active, and are dependent on a government pension of about R1 270-R1 290 per month.15,19

Although only 28% of participants had utilised oral health services in the past 12 months, participants had normative oral care needs, There was a caries experience of 46%, 26% required oral hygiene care, 32% required periodontal treatment and over half (64%) felt that they needed dental treatment, This differs from the results reported by Fiske who conducted a similar study in the inner city area of London, He found that with the utilisation rate of 14%, amongst the 302 participants who had high dental care needs, only 39% of them perceived the need for dental care.7

In general, the perception of need for oral healthcare was higher than the normative oral health need; however participants did not express their needs because of the barriers experienced, The availability of oral health services does not appear to be one of the barriers as only 8% reported that they did not attend due to the lack of availability of services, Geographic accessibility was in addition not a barrier as only 1,3% reported that they lived more than 5km from the services, However, accessibility to adequate transport was reported as a barrier by 16,2% of the participants, This indicates that although the oral health services may have been at close proximity to the retirement villages, a quarter of participants experienced difficulty in getting to the clinics, and this may have been attributed to the challenges of availability of suitable transport and limited mobility.12

Fifty three percent (52,7%) reported that they were unable to afford treatment, The perception that they could not afford treatment was surprising given that the elderly in South Africa have access to free primary and secondary health care services in the public health sector,11 This misconception became a barrier possibility due to the cost of transport and the fear of the unknown costs of dental treatment,8 Some may not have been offered exemptions from fees upon accessing public health facilities, as reported by ljumba & Padarath.20

The logistic regression analysis demonstrated that perceived need was significantly associated with future utilisation particularly in terms of the level of satisfaction the elderly had with the status of their oral health (Table 6), Those that were generally satisfied with their oral health status irrespective of their normative needs would less likely see the need to visit a dentist, This result was consistent with other published studies as it has been shown that some elderly have lower expectations of good health as they age, and that if they do not believe that their condition will worsen by not consulting a health practitioner, they will not seek medical help,8,9,12 In addition, some participants may not have seen the need for dental care as priority, as first concern may have been given to those chronic conditions impairing their activities of daily living.12

The barriers identified in the study can be summarised into those reported by participants and those which will influence future utilisation, Frequently reported were the inability to afford services, lack of transport and the fear of dentists, Long distances, lack of social support and long waiting times were not significantly reported as confirmed by the literature,7,8,10,11 Those barriers indicated to predict future utilisation included advancing age, living with a partner and low perception of need, These predictors are in line with current literature8,10,12 except for living with a partner, In terms of social support in the context of the study, it was found that those living with partners were most frequently males and therefore the result could have been confounded by the fact that men are generally low users of medical services.21

LIMITATIONS

The data was skewed in favour of the white population, This may have been due to the historical fact that the elderly from non-white groups preferred to retire with extended family members and considered residing in retirement villages as "un-cultural",22 However this limitation was balanced by the study population being predominantly from a low-socio economic class, which is representative of the general elderly population in Johannesburg, As free oral health services were offered to all who participated, individuals were more likely to volunteer and this may have influenced the perceived need score.23

CONCLUSION & RECOMMENDATIONS

Although normative and perceived needs for oral health care were identified amongst participants, less than a third (28%) of the study population had accessed dental care in the past 12 months, due to the barriers experienced, mainly the perceptions that dental service costs were unaffordable and that transport was inadequate, Perceived need was found to significantly influence future utilisation.

Based on the study findings, it is suggested that the barriers of cost, transport and perceived need could be addressed by expanding on oral health outreach programmes targeted for the elderly. In addition, awareness needs to be raised on the dental services available and the user fee exemptions at all public health facilities in South Africa.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the individuals who assisted in the research. The study was funded from the Faculty Research Committee Grants of the University of the Witwatersrand.

References

1. Locker D, Clarke M, Payne B. Self-perceived oral health status, psychological wellbeing, and life satisfaction in an older adult population. Journal of Dental Research 2000; 79: 970-5. [ Links ]

2. Slade GD, Locker D, Leake JL. Price, S.A and Chao, I. Differences in oral health status between institutionalized and noninstitutionalized older adults. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 1990; 18: 272 -6. [ Links ]

3. Kandelman D, Petersen PE, Ueda H. Oral health, general health, and quality of life in older people. Special Care Dentistry 2008; 28(6): 224-36. [ Links ]

4. WHO. Oral Health: Important target groups; 2008. Available on: http:www.who.int/oral_health/action/groups/en/index1.html. Accessed [15/12/2011], [ Links ]

5. Petersen PE, Yamamoto T. Improving the oral health of older people: the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 2005; 33: 81-92. [ Links ]

6. Petersen P, Kandelman D, Ogawa H. Global oral health of older people - Call for public health action. Community Dental Health 2010; 27: 257-68. [ Links ]

7. Fiske J, Gelbier S, Watson R. Barriers to dental care in an elderly population resident in an inner city area. Journal of Dentistry 1990; 18: 236-42. [ Links ]

8. Borreani E, Jones K, Scambler S, Gallagher J. Informing the debate on oral health care for older people: Gerodontology, 2010 ; 27: 11-8. [ Links ]

9. Machado LP, Camargo MBJ, Jeronymo JCM, Bastos GAN. Regular use of dental services among adults and older adults in a vulnerable region in Southern Brazil: Rev Saude Publica. 2012; 46(3):1-7 [ Links ]

10. Thomas, S. Barriers to seeking dental care among elderly in a rural South Indian population. Journal of the Indian Academy of Geriatrics 2011; 7: 60-5. [ Links ]

11. Goudge J, Gumede T, Russel S, Gilson L, Mills A. The SACOCO Study: Poor Households and the Health System. Written submissions to the Public Inquiry into access to health care system 2007. [ Links ]

12. Kiyak H, Reichmuth M. Barriers to and enablers of older adults' use of dental services. Journal of Dental Education 2005; 69: 975-86. [ Links ]

13. Van Wyk PJ. National Oral Health Survey - South Africa 1988/89. 1st edn. Pretoria: Department of Health, 1994. [ Links ]

14. Bhayat A, Cleaton-Jones P Dental clinic attendance in Soweto, South Africa, before and after the introduction of free primary dental health services. Community Dent Oral Epidemiology 2003; 31: 105-110. [ Links ]

15. Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC). National Oral Health Survey: Sociological and Epidemiological Questionnaire. In: National Oral Health Survey: South Africa 1988/89.Dept of Health 1994; Annexure 1. [ Links ]

16. Van Wyk C, Van Wyk, PJ. Trends in dental caries prevalence, severity and unmet treatment need levels in South Africa between [ Links ]

17. World Health Organisation. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods. Third Edition. WHO, Geneva 1987, [ Links ]

18. Stats SA. Living conditions of households in South Africa. Available on www.statssa.gov.za. Accessed [24/02/12]; 2011. [ Links ]

19. South African Government Services. Available on: www.serv-ices.gov.za. Accessed [07/12/2013], [ Links ]

20. Ijumba P Padarath A. South African Health Review, Durban. Health Systems Trust 2006. [ Links ]

21. Harris B, Goudge J, Ataguba JE, McIntyre D, Nxumalo N, Jik-wana S et al. Inequities in access to health care in South Africa. Journal of Public Health Policy 2011; 32:102-23. [ Links ]

22. Viljoen S. Accommodation of the black aged. In: M.Ferreira, LS. Gills.V. Moller (eds.) Aging in South Africa-social research papers. Pretoria: HSRC; 1989: 83-94. [ Links ]

23. Zola I. Pathways to the doctor: from person to patient. Social Science and Medicine 1972; 7:677-89. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

MP Molete:

Department of Community Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences

University of the Witwatersrand

E-mail: Mpho.molete@wits.ac.za