Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Dental Journal

On-line version ISSN 0375-1562

Print version ISSN 0011-8516

S. Afr. dent. j. vol.69 n.7 Johannesburg 2014

ETHICS CASE

Ethical management of patients with hearing impairments

S Naidoo

BDS (Lon), LDS.RCS (Eng), MDPH (Lon), DDPH.RCS (Eng), MChD (Comm Dent), PhD (US), PG Dipl Int Research Ethics (UCT), DSc (UWC). Senior Professor and Principal Specialist, Faculty of Dentistry, University of the Western Cape. Department of Community Dentistry, Private Bag X1, Tygerberg 7505. E-mail: suenaidoo@uwc.ac.za

SCENARIO

Mrs Zuma is a 75 year old patient who has been living alone for six years since her husband died. Her hearing has deteriorated over the past few years. She has lost all her natural teeth and has been wearing upper and lower dentures for the past eight years. Recently she noticed that her dentures had become very loose and she has been having difficulty eating. She has been putting off her trip to the dentist because she is very nervous. When she eventually makes an appointment, her first words are "I don't really like dentists ...". What can one do to minimise her anxiety, what are the ethical duties of confidentiality and how can one give an empathetic response to Mrs Zuma's comment that she "doesn't like dentists" ?

COMMENTARY

Communication and a trusting relationship between a patient and the dental professional rely on a total respect for patient autonomy. Good communication is fundamental to good clinical practice, as it allows the practitioner to inform, be informed and to exchange information so as to understand the patient's reason for attendance, their medical history, to explain treatment needs, obtain valid informed consent and provide appropriate preventive advice. It builds patient rapport and trust, thereby reducing patient anxiety while enhancing patient satisfaction and compliance.1

There are three main elements of communication: words, tone of voice and body language.1 Selecting and using the "right" words account for only a small part of communication and are used to transmit what we want to say. All communication needs to be clear and jargon-free and checking patient understanding is a useful way of monitoring comprehension. Verbal communication accounts for only 7% of transmission. Tone of voice is estimated to convey 33% and body language or non-verbal communication for 60% of the message. Receiving information involves active listening to all elements of communication, including non-verbal and verbal feedback. Attentive listening is indicated by facing the speaker at the same level, leaning forward slightly to signal interest, making appropriate eye contact, uttering encouraging sounds or gestures to continue and reflecting on what has been said. Additionally, reinforcement of messages and a brief summary of the main points help people to remember salient information.2

Communication relies, to a large extent, on seeing and hearing. If one or other of these sensory systems is impaired, the communication process can also be impaired. This can have a profound effect on access to dental services by complicating the appointment making process. In addition, in the dental setting this can have an impact on the ability to ascertain vital information during history taking, to build patient rapport and the provision of effective preventive information can be prejudiced. The communication process can become time-consuming and frustrating for all involved if it is not well managed.3

A variety of patient disabilities impact on "normal" communication and patients who are deaf or hard of hearing, require special consideration in the dental surgery for effective care and management. Deaf is a general term used to refer to people with all degrees of hearing loss, with the level of deafness defined by the quietest sound a person can hear. Hearing impairment or deafness can be congenital, inherited, or acquired as the result of accident, disease, or as part of the ageing process. It can be difficult to recognise deafness, often referred to as the "invisible disability", as there may be no visual clues that the person has a severe hearing loss and even profoundly deaf people may not wear hearing aids. If you have a patient who is deaf, ask them what their preferred method of communication is, record it and ensure it is used. The way in which deaf people communicate often depends on the time in their lives when they lost their hearing. Those who were born deaf, or lost their hearing before learning to speak, will generally be sign language users. People who have lost their hearing in later life, after they have learnt to speak, will generally communicate by lip-reading and speech. Do not assume that a person wearing hearing aids can hear what you are saying, as they may only be able to hear particular sounds or background noise.4

Deaf patients experience difficulties in communication at the dental visit, not responding when called from the waiting room, having erratic interchanges with the dentist and/ or dental assistant and not understanding what will take place in the dental visit.3 They often rely on the use of hearing aids, however power-driven dental instruments such as high-speed drills and scalers may result in a high-pitched whistling interference when operated in close proximity to the listener.

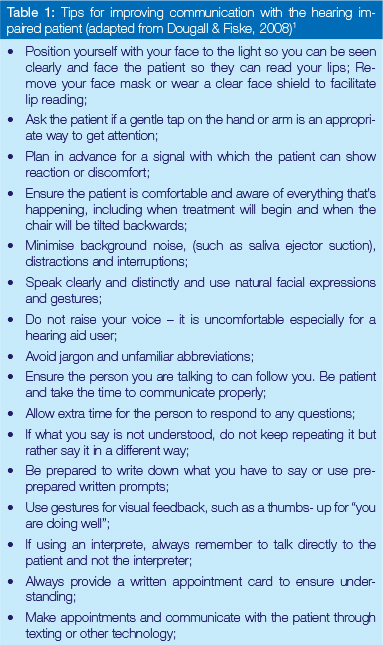

Communicating with someone who is deaf or hard of hearing is not difficult. There are a number of basic rules to enable successful communication (Table 1).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Empathy means putting yourself in the other person's position and with empathic response,s acknowledge their feelings. Dental practitioners must have, or must develop skills to enable them to relate to patients in ways that are both ethical and empathetic, so that people with special needs can have confidence in the dental profession. These interpersonal skills will complement the technical competence of the dentist.

References

1. Dougall A, Fiske J. Access to special care dentistry, Part 2. Communication. Br Dent J 2008; 205:11-21. [ Links ]

2. Wanless M. Communication in dentistry - why bovver? Oral Health Report 2007; 1(2): 2-5. [ Links ]

3. Champion J, Holt R. Dental care for children and young people who have a hearing impairment. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 155-9. [ Links ]

4. Fiske J, Dickinson C, Boyle C, Rafique S, Burke M. Managing the patient with a sensory disability. In Special Care Dentistry. pp 27-42. London: Quintessence Publishing, 2007. [ Links ]

Recommended Reading

1. Ethics, values and the law. DPL Dental Ethics Module 9: Confidentiality. 2009 [ Links ]

2. Moodley K, Naidoo S. Ethics and the Dental Team. Van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria, 2010. [ Links ]

Readers are invited to submit ethical queries or dilemmas to Prof, S Naidoo, Department of Community Dentistry, Private Bag X1, Tygerberg 7505 or email: suenaidoo@uwc.acza