Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Bothalia - African Biodiversity & Conservation

On-line version ISSN 2311-9284

Print version ISSN 0006-8241

Bothalia (Online) vol.53 n.1 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38201/btha.abc.v53.i1.10

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

An online survey on user perceptions of natural science collections in South Africa

Shanelle RibeiroI; Terry ReynoldsII; Bernhard ZipfelIII; Mashiane S. MothogoaneIV; Anthony MageeV, VI

ISouth African National Biodiversity Institute, Natural Science Collections Facility, Private Bag x1 01, Pretoria 01 84, South Africa

IIIziko Museums of South Africa, P.O. Box 61, Cape Town 8000, South Africa

IIIEvolutionary Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, Wits 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa

IVSouth African National Biodiversity Institute, National Herbarium, Private Bag x101, Pretoria 0184, South Africa

VSouth African National Biodiversity Institute, Compton Herbarium, Private Bag X7, Claremont 7735, South Africa

VIDepartment of Botany and Plant Biotechnology, University of Johannesburg, P.O. Box 524, Auckland Park 2006, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: In South Africa, and globally, the value of natural science collections for scientific research is not widely recognised and has led to its marginalisa-tion, which in turn has resulted in low funding, staffing and use of the collections

AIM AND OBJECTIVES: To this end, as part of the effort to increase understanding and appreciation of the collections, a cross-sectional web-based survey was administered to users of natural science collections (NSCs) in South Africa. The objectives of the study were to identify the perceived value of NSCs to the research community; perceived or experienced barriers in accessing NSCs and associated data for use in research; perceptions of NSCs' current performance in serving the needs of stakeholders; and how performance is judged and what the expectations are to improve future performance of NSCs to better serve the needs of stakeholders

METHODS: The survey consisted of 26 questions, distributed by email to relevant researcher community mailing lists, and posted on relevant social media groups. The survey was completed by 131 respondents

RESULTS AND CONCLUSION: The study indicated the overall perception of the importance of NSCs and their accessibility to the student and researcher community in South Africa and internationally to be extremely important to their research. Lack of funding for operations and staff impedes the ability of researchers and other users alike in using NSCs to optimise their research and contribute to issues of societal concern. A sustained commitment is required from NSC institutions to work together to solve various challenges, including improvement in serving stakeholder needs, which will in turn assist with demonstrating the value of NSCs to policymakers, in order to lobby for support and funding. Improved recognition of the importance of NSCs for research by the scientific community will assist NSCs in demonstrating their impact. Political priority should also be given to the long-term upkeep and ongoing assistance of institutional infrastructures

Keywords: natural history collections, natural science collections, natural history museums, collections management.

Introduction

South Africa has an estimated 100 natural science collections at approximately 40 institutions (NSCF 2019). Together they provide over 18 million objects or specimens representing about 100 000 different species of plants, animals and fungi, which have been accumulated over the last 200 years and represent life on earth since its origins (NSCF 2019).

The documentation and study of natural science specimens underpin our understanding and further research into the diversity of life, its origins and evolution, and its distribution in space and time. This contributes to biodiversity conservation, pest and disease control, solving crime, public health, food security; and allows for future predictions, including for climate change impacts, that can inform decision-making by policymakers (Suarez & Tsutsui 2004; Figueira & Lages 2019; Jacobs 2020). The collections also constitute an invaluable record of the natural heritage of the subcontinent (Davison 1994). Museum exhibitions, events and lectures based on biological collections contribute to a greater public understanding and appreciation of nature, both local and worldwide, and why it needs to be conserved. NSCs directly contribute to the success of a museum by providing knowledge to local communities but could also indirectly contribute to the growth of tourism and the local economy (NatSCA 2005; Powers et al. 2014; Proa & Donini 2019).

The impacts or outcomes of research and data emanating from collections, however, are generally indirect or downstream, which means that their significance is often not well understood or recognised, resulting in a lack of appreciation of this infrastructure. This in turn has resulted in low funding, staffing and use of the collections in South Africa and globally (Drew 2011; Hamer 2012). Several initiatives have been directed towards addressing dwindling capacity and resources for NSCs and associated research in South Africa. The establishment of the Southern African Society for Systematic Biology (SASSB) in 1999 and the South African Biosystematics Initiative (SABI) in 2002, both aimed to address the country's declining capacity in biological systematics and taxonomy, and to increase public appreciation of the value of systematics and natural science collections (SASSB 2023). Despite these efforts, capacity and resource challenges persist for NSCs.

An assessment of South African zoological research collections (Hamer 2012) recommended two actions required to improve engagement with collections: 1) multilateral discussions between relevant government departments under which the collections' institutions are governed; and 2) making use of the collections to address questions of societal relevance. These recommendations are currently being addressed by the Natural Science Collections Facility (NSCF) project, funded by the Department of Science and Innovation through the establishment of a virtual network of South African institutions housing NSCs. This virtual network is directed towards collaboratively dealing with challenges faced by the South African NSC community.

One of the objectives of the NSCF is to research and demonstrate the importance and use of the collections and data by the global research community in solving issues of societal relevance and protecting the systems that sustain life. This is critical to ensure the long-term sustainability of the collections.

A survey by Astrin and Schubert (2017) captured a snapshot of the values and opinions regarding natural history collections from 525 poll participants from pre-dominantly North America and Europe, mostly based in academia (41%) and at natural history institutions (32%), or students (10%). It was found that natural history collections are intriguing or interesting places for almost all respondents. Fundamental research, collection care and educating the public were the three most often selected natural history collections' core roles. The general importance of vouchering and the treatment of type specimens were considered to be satisfactory. Molecular vouchers, data accessibility, sample documentation and taxonomic expertise at the natural history collections were considered to deserve more attention, with less satisfaction expressed. Insufficient funding was the strongest concern of most survey participants. Such a study has, to date, not been carried out on South African NSCs.

To this end, as part of the effort to increase understanding and appreciation of the collections, a survey of the stakeholder community's perceptions of the value and current performance of South African NSCs was conducted. The study aimed to identify the perceived value of NSCs to the stakeholder community; perceived or experienced barriers in accessing NSCs and associated data for use in research; perceptions of NSCs' current performance in serving the needs of stakeholders; how NSC performance is judged and what the expectations are to improve future performance of NSCs to better serve the needs of stakeholders.

Research method and design

Target group

The target group of the survey consisted of the user community who access and use specimens, images of specimens and specimen data from South African NSCs to conduct research or related work. This included students, taxonomists, Environmental Impact Assessment experts, citizen scientists, and scientists in the fields of climate change, ecology, ethnobotany, evolution, nature conservation, pest and disease control, and agriculture.

Study design

A cross-sectional web survey design was employed for the study. The survey collected responses for a period of two months.

The survey link was distributed by email to relevant researcher community mailing lists, and to collections curators and managers at the NSCF partner institutions, to share with users of their respective collections. A link to complete the survey was also posted on natural science and researcher community Facebook pages and groups.

Methods

The survey, adapted from Astrin and Schubert (2017), consisted of 26 questions (Annexure A), and was set up and administered through the Survey Monkey website. The first seven questions constituted of background questions and only two of these were compulsory. The compulsory questions prompted participants to state in which discipline/s they conduct their research, and whether they were a South African resident. This enabled analysis of data based on the type of researcher, and analyses of perceptions from both the local and international communities.

The remainder of the survey questions were not compulsory and were divided into the specific objectives of the research. Eight questions related to Objective 1: perceived value of NSCs to the research community; two questions related to Objective 2: perceived or experienced barriers in relation to access to natural science collections and associated data for use in applied research; six questions related to Objective 3: perceptions of NSCs' current performance in serving the needs of applied research, and three questions related to Objective 4: how performance is judged and what future expectations for performance are.

Data analysis

The results from the survey were analysed using the Survey Monkey (www.surverymonkey.com) outputs summary tool and Microsoft Excel. The filter tool was applied to determine: a) types of respondents based on residency status, employment sector, relevant research discipline, and b) the different types of services that collections offer. The two open-ended questions, relating to barriers to access experienced and the area that NSCs can improve on most, were analysed by grouping answers according to themes.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance

The survey study was approved by the South African National Biodiversity Institute Animal Research Ethics and Scientific Committee, with reference number SANBI/RES/P2021/21.

Risks or negative impacts associated with research and mitigation

To ensure no harm came to participants, the respondents were able to complete the survey anonymously. In the case where respondents had chosen to provide their names, the risk to participants was reduced by not naming any individual or their affiliation in the survey results.

Recruitment and informed consent

An informed consent form (Annexure B) including the aim of the study and details regarding the protection of participants' personal information was prepared for this study and was distributed to participants to complete and sign. Participation was voluntary and participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence.

Data protection

The raw data from the study is stored in a password-protected file, and the password is only available to the first author. The raw data, which includes participant details, will be deleted upon completion of the research.

Results

Profile of respondents

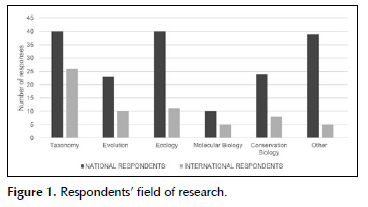

Of the 131 responses received, 74% of respondents were South African residents and 26% were international. Respondents mostly indicated that they worked in more than one discipline, with most national and international respondents working in the disciplines of taxonomy and ecology (as depicted in Figure 1).

The disciplines listed on the 'other' option by respondents included geomorphology, biodiversity informatics, soil science, plant virology, biogeography and genetics.

Of those respondents who indicated their place of work, 47 indicated they were employed at universities, 25 at science and research councils, 13 at museums, 10 as consultants at private companies, three at conservation trusts/councils, and two were employed in government departments. Eleven respondents indicated that they were students. The majority of international respondents were employed at universities. Responses from those employed at government departments were underrepresented. This suggests that either government departments were not sampled adequately, or only a small number of government departments use basic taxonomic outputs.

The value of NSCs to the researcher community

Access to specimens and data

The results indicate that respondents access natural science specimens or data for their research daily (23%), weekly (15%), monthly (13%), biannually (16%), annually (11%), and less frequently (22%). These respondents indicated that they worked with one or more of the following types of specimens and data: animal specimens and data (52%), followed by plant specimens and data (23%), fossil specimens and data (10%), and fungi specimens and data (1%). Fourteen per cent of respondents indicated that they worked with other specimens, which included soil, shells and bacteria. The majority (97%) of international respondents worked with animal and plant specimens and data.

Contribution of access to specimens and data to research

For Question 14 respondents were asked, 'How important is access to NSCs (specimens, associated data and collaboration with NSC staff) to your research?' Responses were indicated on a Likert scale (1 - not at all, 2 - slightly, 3 - moderately, 4 - very, 5 - extremely). Seventy-one per cent (71%) and 17% of respondents indicated access to NSCs as 'extremely' and 'very important', respectively.

Eighty-nine per cent (89%) of respondents indicated that access to NSC specimens directly contributed to their research, with access to NSC specimens referring to loans of physical specimens and tissue/DNA samples; images of specimens; laboratory space and equipment; specimen data; expertise and advice from curators/researchers; identification services; depositing collected specimens; and/or collaborations with associate researchers.

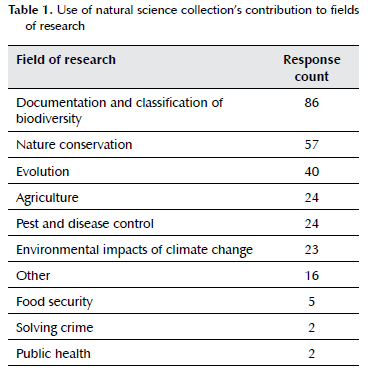

Respondents indicated that their research using NSCs contributed to one or more of the fields listed in Table 1.

Seventy per cent (70%) of respondents indicated that access to NSC specimens and data contributed to the curation process of the collection and/or led to the formation of collaborations with NSC staff. Sixty-four per cent (64%) of respondents indicated that they inform the NSC once their research has been published and/or send the NSC a copy of the published paper.

Perceived or experienced barriers to access

For Question 17 'Do you find the access request procedure overly onerous?', 77 respondents answered no, 11 indicated yes and 27 were uncertain. Twenty-one respondents (18%) indicated that they have been denied access to specimens or data. Responses to the open-ended question on how access was denied, organised according to themes, included:

• Staff shortages - seven responses.

• Institutional policy (on destructive sampling, loaning of physical type specimens) - three responses.

• Collection closed (due to renovations or Covid-19) -three responses.

• Institution access committee decision - two responses.

• Perceived bias by collection curator - two responses.

• Embargo on specimens due to pending research -one response.

A comparison of national and international respondents indicated that 14% of national respondents and 21% of international respondents experienced barriers to access.

Perceptions of NSCs' current performance in serving the needs of research

Responses to the six questions dealing with the perceptions of NSCs' current performance in serving the needs of applied research are summarised below:

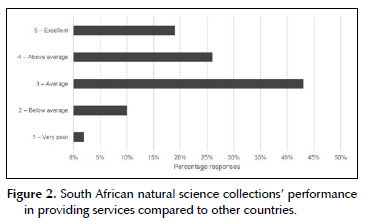

The majority of respondents (43%) indicated that South African NSCs perform 'average' in providing services compared to NSCs in other countries. Twenty-six per cent (26%) of respondents indicated that the NSCs performed 'above average', and 19% of respondents indicated that NSCs performed 'excellent' in providing services compared to NSCs in other countries (Figure 2).

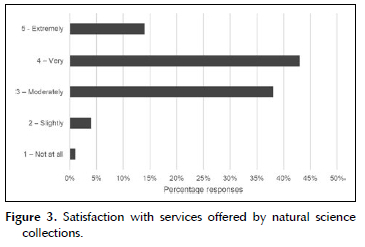

The majority of respondents (43%) indicated that they were 'very happy' with services offered by South African NSCs, 14% of respondents indicated that they were 'extremely happy' with services offered and 39% of respondents indicated that they were 'moderately happy' (Figure 3).

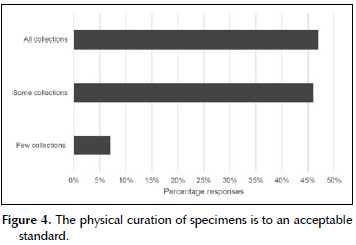

Forty-seven per cent (47%) of respondents indicated that 'all' collections' physical curation was to an acceptable standard, and 46% indicated that 'some' collections' physical curation was to an acceptable standard (Figure 4).

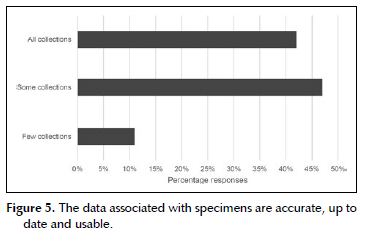

The majority of respondents (47%) indicated that the data associated with the specimens were up-to-date, accurate and usable for 'some' collections. Forty-two per cent (42%) of respondents indicated that the data associated with the specimens were up-to-date, accurate and usable for 'all' collections (Figure 5).

Perceived performance according to collection type is summarised in Table 2. The majority of respondents were 'moderately happy' with the services offered for animal collections, 'very happy' with services offered for plant collections and 'extremely happy' with services offered for fossil collections. The majority of respondents indicated that the physical curation of some animal collections, some plant collections and all fossil collections were to an acceptable standard. Most respondents indicated that the data associated with specimens were up-to-date, accurate and usable for some plant, some animal, and some fossil collections.

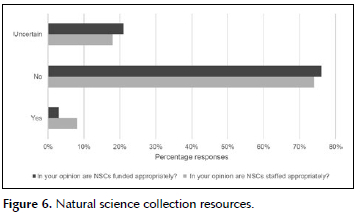

The majority of respondents (76%) indicated that NSCs were not funded appropriately in their opinion and most respondents (74%) indicated that NSCs were not staffed appropriately in their opinion (Figure 6).

Performance: how is it judged, and what are the future expectations

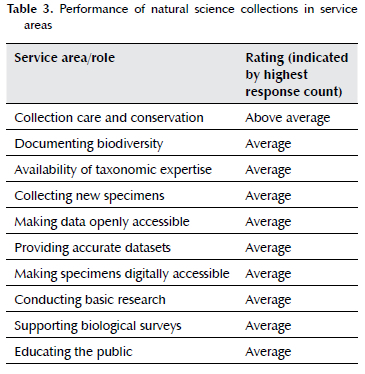

The five most important roles of NSCs, as identified by 114 respondents, were: collection care and conservation; documenting biodiversity; availability of taxo-nomic expertise; collecting new specimens; and making data openly accessible.

National and international respondents rated NSC performance in the below-mentioned service areas as average, except for collection care and conservation performance, which was rated as above average (Table 3).

The majority of respondents believed that the areas in which NSCs should improve on most were an increased staff complement (25), followed by collection care and conservation (19) and availability of taxonom-ic expertise (19) (Figure 7).

Discussion

Outline of the results

Perceived value of NSCs to the research community

A mutually beneficial relationship exists between the users and the collections (including staff expertise and access to specimens and data), with a large percentage of respondents indicating that access to NSC specimens directly contributed to their research and/or the curation process of the collection, which often leads to the formation of collaborations with staff. This is supported by the wide use of the collections as reported by the 16 NSCF partner institutions reporting an average of 1 157 national visitors using the collections per year, 204 international visitors using the collections per year and an average of 479 454 data records provided to external users per year over a five-year period from 2017 to 2021 (NSCF 2022).

To encourage and support increased funding for NSCs, there is an argument that the scientific community must improve recognition of the role of NSCs in research so that NSCs can more effectively demonstrate their impact (Miller et al. 2020). While a large percentage of the respondents (64%) indicated that they inform the NSC once their research has been published and/or send the NSC a copy of the published paper, there is a lack of a standardised method of citation for collections and institutions for tracking publications. This has been one of the challenges associated with attribution for NSCs and a possible solution is to acknowledge NSCs along with their specimens through citation of the institutions (or their individual departments) by Digital Object Identifier (DOI, found in GBIF) in concert with complete voucher lists containing sample accession numbers (Miller et al. 2020).

Perceived or experienced barriers in relation to access and current performance in serving the needs of research

Many collections are understaffed or not staffed at all, and the loss of even a single staff member frequently results in a collection being neglected and unused (Hamer 2012). Staff shortages slow the distribution of specimen loans and provide fewer resources for visitors at a time when collections are being used by more researchers in increasingly diverse fields (Schindel & Cook 2018). Although the majority of respondents did not find the access procedure to specimens and data overly onerous and did not experience barriers to access, the majority of respondents indicated that very few collections fared extremely well (Table 1) in serving the needs of research and indicated that NSC current performance was linked to a lack of staffing and funding.

Institutions that hold NSCs have indeed experienced insufficient funds for operations and staffing from governing bodies to care for the collections under their control (Herbert 2001). The 1997 White paper on the conservation and sustainable use of South Africa's biological diversity stated that South Africa's museums and other collection-based institutions were facing serious funding problems, endangering existing collections and the professional staff of these institutions (Herbert 2001). A comprehensive inventory and review of South African NSCs commissioned by the National Research Foundation in 2011 also highlighted several significant challenges with the collections, which meant that their full potential as a national research infrastructure was not being realised and several important collections were at risk (Hamer 2012). The establishment of the NSCF is geared toward collaboratively addressing the challenges that NSCs face, with investment in infrastructure and research equipment upgrades, capacity development and appointment of short-term staff to address collections at risk. However, funding for operations and appointment of permanent staff at NSCs do not fall within the NSCFs ambit, but rather the national, provincial and municipal departments from which the collections receive the core of their funding.

Many (if not all) South African institutions housing NSCs that are accessible to external researchers have suffered further financial losses during the COVID-19 period. The impact of the pandemic on the South African economy has resulted in subsidy cuts from the national, provincial and municipal departments, which has exacerbated the financial constraints (NSCF 2022). Thus, the challenges of sustainability from a funding and staffing point of view have indeed worsened and will have a negative impact on the service delivery of NSCs to the research community. NSCF partner institutions report that these budget cuts inevitably result in the 'freezing' of what the government perceives to be non-critical vacancies, even though they are critical to the performance of NSCs in serving the needs of research. Examples of such vacancies include natural science curators, collection managers and research assistants.

How performance is judged and what the future expectations for performance are

The results indicated that respondents believed that the most important roles of NSCs were also the areas in which they should focus and improve on in future. These included collection care and conservation, documenting biodiversity, availability of taxonomic expertise, collecting new specimens and making data openly accessible. This echoes the views of curators who see 'the collections as serving a scientific and research purpose rather than a cultural or historical purpose, with taxonomic research and reference collection or identification value rated as the most important functions of the collections, and cultural, aesthetic, and tourism value rated as the least important' (Hamer 2012:2).

To improve and address gaps in collection care and conservation, the NSCF partner institutions have collaboratively produced policy guidelines, standards and procedures for collections and data management, published as a freely available Collections Management and Conservation Manual (NSCF 2021). The NSCF also developed a Collections Management and Conservation course linked to the manual, with webinars and tutorials accessible on the NSCF website at https://nscf.org.za/resources/collections-management/, in an effort to improve collection and data management practices across NSC institutions.

One of the main criteria for participation of collection institutions in the NSCF is that the collections and data are openly accessible to external researchers and students. This was agreed upon and accepted by the institutions that are participating in the NSCF (NSCF 2022). For data, the NSCF objective is that the specimen data sets of NSCF partner institutions will be made accessible through a single portal. While the development of this portal is under way, submission of data to the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) platform is encouraged and technical support for this is provided for institutions that require this (NSCF 2022).

Although 'educating the public' scored low on overall importance compared to other roles, respondents believed that NSCs should improve in this area. This can be linked to the fact that collections are kept behind the scenes and, while NSCs have an underestimated value to society in terms of providing the foundational information to promote national/global economic, historic and scientific prosperity, communicating their value to society has not been given adequate attention. Although some NSCF partner institutions have made a concerted effort to focus on improving learner education and public understanding of the importance of NSCs, more work is required in this area (NSCF 2022). Specimens and natural history collections typically offer a perfect platform for the public to engage in science and support the collections through volunteer programs and community science activities (Sforzi et al. 2018). Through public education and outreach, training programmes and research collaborations, NSCs have the potential to increase participation of historically under-represented groups in museum sciences, which can increase public investment, while benefiting participating communities (Miller et al. 2020). Promoting and collaborating with citizen science initiatives also hold, often untapped, opportunities for promoting the collections. Citizen science programmes like iSpot and iNaturalist encourage scientific enquiry and raise public awareness of the value of protecting the environment (Silvertown et al. 2015).

Practical implications

Lack of funding for operations and staff impedes the ability of researchers and other users alike in using NSCs to optimise their research and contribute to issues of societal concern. Political priority should be given to the long-term upkeep and ongoing assistance of institutional infrastructures by national, provincial and municipal government departments.

Limitations of the study

Due to the varied state of NSCs in the country, the study aimed to capture the general perceptions and experiences of users of NSCs, and not at an individual collection or institution level. The NSCF, through funding received from the Department of Science and Innovation, will be conducting comprehensive collection assessments during 2023, with an aim to address issues and challenges, and lobby for support at an individual collections level. Future research linking user perceptions and the outcomes of the assessments holds the potential to provide a three-hundred-and-sixty-degree view of the state of collections and recommendations for specific targeted interventions.

Limitations that could have affected the response rate negatively might be the limited period that the survey was available online (two months), as well as the distribution of the questionnaire by email and through social media only. Given the average number of users of NSCF partner NSCs of 1 192 per year (NSCF 2022), the response rate of the survey was 11%. This was comparable with the finding of an examination of response rates for web-based surveys conducted by Saunders et al. (2016), which revealed that online surveys received rates of response of 10 to 20 per cent.

Recommendations

• The scientific community should improve recognition of the importance of NSCs in research for NSCs to successfully demonstrate their influence. This would promote and support more funding for NSCs.

• A sustained commitment from partner NSCF institutions to work together to solve various challenges is required. This includes improvement in serving stakeholder needs, which will in turn assist with demonstrating the value of NSCs to policymakers in order to lobby for support and funding.

• NSCs should improve their outreach efforts and collaborations with stakeholders, including the public, learners and citizen science initiatives, to encourage appreciation and support of NSCs.

Conclusion

This study indicated the overall perception of the importance of NSCs and their accessibility to the student and researcher community in South Africa and internationally to be extremely important to their research. Access to physical specimens, associated data, staff expertise and formation of collaborations all directly contribute to research in the fields of taxonomy, nature conservation, evolution, agriculture, pest and disease control, environmental impacts of climate change, food security, solving crime and public health. In turn, users contribute to the curation process at NSCs and form research collaborations with collection staff. The scientific community can further support NSCs by improving recognition of the role of NSCs in research so that NSCs can more effectively demonstrate their impact.

Lack of funding for operations and staff impedes the ability of researchers and other users alike in using NSCs to optimise their research and contribute to issues of societal concern. Political priority should be given to the long-term upkeep and ongoing assistance of institutional infrastructures. The establishment of the NSCF through the Department of Science and Innovation has made considerable strides in forming a network of institutions, which enable sharing of resources and expertise, working towards implementing international curation and data management standards across institutions, and advocating for open access data policies, as well as conducting research that answers questions of societal concern. The NSCF project is still in its infancy and will require a sustained commitment from partner NSC institutions to work together to solve various challenges, including improvement in serving stakeholder needs, which will in turn assist with demonstrating the value of NSCs to policymakers in order to lobby for support and funding. This is especially true within a country with competing priorities for basic service delivery, alleviation of poverty and high unemployment rates.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms Fulufhelo Tambani, the NSCF Science Communication Officer, for distributing the survey on the relevant social media platforms, and Prof. Michelle Hamer, the NSCF Lead, for reviewing and providing comments that improved the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

S.R. (South African National Biodiversity Institute) conducted the data analysis and prepared the first draft of the paper. T.R. (Iziko Museums of South Africa), B.Z. (University of the Witwatersrand), M.S.M. (South African National Biodiversity Institute) and A.M. (South African National Biodiversity Institute) reviewed and edited the paper for final publication. All authors contributed to the development of the study.

References

Astrin, J.J. & Schubert, H.C., 2017, 'Community perception of natural history collections-an online survey', Bonn Zoological Bulletin 66, 61-72, https://bonn.leibniz-lib.de/de/forschung/publikationen/community-perception-of-natural-history-collections-an-online-survey. [ Links ]

Davison, P., 1994, 'Museum collections as cultural resources', South African Journal of Science, 90(8-9), 435, 436, https://hdl.handle.net/10520/AJA00382353_7799. [ Links ]

Drew, J., 2011, 'The Role of Natural History Institutions and Bioinformatics in Conservation Biology', Conservation Biology 25(6), 1250-1252, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01725.x. [ Links ]

Figueira, R. & Lages, F., 2019, 'Museum and Herbarium Collections for Biodiversity in Angola', in B. Huntley, V. Russo, F. Lages & N. Ferrand (eds.), Biodiversity of Angola, Springer, Cham, https://doi.org//10.1007/978-3-030-03083-4_19. [ Links ]

Hamer, M., 2012, 'An assessment of zoological research collections in South Africa', South African Journal of Science 108(11-12), https://sajs.co.za/article/view/9769. [ Links ]

Herbert, D.G., 2001, 'Museum natural science and the NRF: crisis times for practitioners of fundamental biodiversity science: science policy', South African Journal of Science, 97(5), 168-172, https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/EJC97331. [ Links ]

Jacobs, A., 2020, 'The importance of natural science collections in South Africa', South African Journal of Science 116(11-12), https://sajs.co.za/article/view/8145. [ Links ]

Miller, S.E., Barrow, L.N., Ehlman, S.M., Goodheart, J.A., Greiman, S.E., Lutz, H.L., Misiewicz, T.M., Smith, S.M., Tan, M., Thawley, C.J. & Cook, J.A., 2020, 'Building natural history collections for the twenty-first century and beyond', BioScience 70(8), 674-687, https://doi.org/10.1093/bios-ci/biaa069. [ Links ]

NatSCA, 2005, 'A Matter of Life and Death. Natural Science Collections: Why Keep Them and Why Fund Them?', viewed 9 August 2021, from https://www.natsca.org/collections-publications. [ Links ]

NSCF, 2019, NSCF Overview [Online], viewed 9 August 2022, from https://nscf.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/2019_11_26-NSCF-brochure-1.pdf. [ Links ]

NSCF, 2021, Collection Management & Conservation Manual, viewed 25 November 2022, from https://nscf.org.za/collection-management-and-conservation-manual/. [ Links ]

NSCF, 2022, 5-year Review Report, Pretoria, viewed 25 November 2022, from https://nscf.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/NSCF-Self-Evaluation-July-2022-V02.pdf. [ Links ]

Powers, K.E., Prather, L.A., Cook, J.A., Woolley, J., Bart Jr, H.L., Monfils, A.K. & Sierwald, P, 2014, 'Revolutionizing the use of natural history collections in education', The Science Education Review 13(2), 24-33, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1057153.pdf. [ Links ]

Proa, M. & Donini, A., 2019, 'Museums, nature, and society: The use of natural history collections for furthering public well-being, inclusion, and participation. Theory and Practice', The Museum Scholar, Volume 2, https://articles.themuseumscholar.org/2019/07/01/tp_vol2proadonini/. [ Links ]

SASSB, 2023, 'History', viewed 22 February 2023, from http://sassb.co.za/. [ Links ]

Saunders, M., Lewis, P & Thornhill, A., 2016, Research Methods for Business Students, 7th edition, Pearson, Essex. [ Links ]

Schindel, D.E. & Cook, J.A., 2018, 'The next generation of natural history collections', PLoS Biology 16(7), e2006125, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2006125. [ Links ]

Sforzi, A., Tweddle, J., Vogel, J., Lois, G., Wägele, W., Lake-man-Fraser, P, Makuch, Z. & Vohland, K., 2018, 'Citizen science and the role of natural history museums', in S. Hecker, M. Haklay, A. Bowser, Z. Makuch, J. Vogel & A. Bonn (eds.), Citizen Science: Innovation in Open Science, Society and Policy, pp. 429-444, UCL Press, London, https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787352339. [ Links ]

Silvertown, J., Harvey, M., Greenwood, R., Dodd, M., Rosewell, J., Rebelo, T., Ansine, J. & McConway, K. 2015, 'Crowd-sourcing the identification of organisms: A case-study of iSpot', Zookeys 480, 125-146. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.480.8803. [ Links ]

Suarez, A. & Tsutsui, N., 2004, 'The Value of Museum Collections for Research and Society', BioScience 54, 66-74. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0066:T-VOMCF]2.0.CO;2. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Shanelle Ribeiro

E-mail: s.ribeiro@sanbi.org.za

Submitted: 30 November 2022

Accepted: 3 May 2023

Published: 11 July 2023

Supplementary Data

The supplementary data is available in pdf: [Supplementary data]