Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Bothalia - African Biodiversity & Conservation

On-line version ISSN 2311-9284

Print version ISSN 0006-8241

Bothalia (Online) vol.52 n.1 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.38201/btha.abc.v52.i1.4

It is recognised that there are valid circumstances where PADDD is necessary. For instance, to remove redundancy or where a portion or all of the protected area does not meaningfully contribute to the conservation of biodiversity, or where greater accuracy of the contribution of protected areas to biodiversity conservation is required (Cook et al. 2017). PADDD may also be required where the loss of part or all the protected area is required for justifiable and critically important development or land use change that is (at least in the medium- to long-term) overridingly in the public's best interests. In these circumstances, the loss of biodiversity and the protected area estate would need to be compensated or offset in a manner that is equally overriding in favour of biodiversity conservation (Blackmore 2020). These conditions for the use of PADDD do not fit comfortably, if at all, with the amendment of the MPE boundaries.

By issuing the Shongwe Notice, it is evident that the MEC, inter alia:

a. attempted to circumvent the National Ministers' consent obligations,

b. ignored his public trust and other obligations bestowed on him by the NEMPAA,

c. attempted to nullify the MEJCON judgment - an outcome Uthaka Energy (PTY) Ltd was not able to achieve by approaching the Senior Court of Appeal and the Constitutional Court,

d. undermined the pending judicial and appeal processes that are yet to be finalised, and

e. following on from the above two points, displayed a lack of confidence in the rule of law.

In view of this, it may be easily concluded that the action taken by the MEC was an inappropriate use of his powers - perverse in that the MEC used a discretionary provision in NEMPAA to set aside the intent and purpose of the Act.

Should this be the case, the MEC may have catapulted South Africa into the ranks of Brazil and other countries where protected areas are purposefully being downgraded, downsized and degazetted to pave the way for achieving, what appears to be, parochial or partisan objectives and profit-vested interests (Blackmore 2015; de Marques & Peres 2015; Qin et al. 2019; Treves et al. 2019).

Conclusion

In 2014, the then Minister of Environmental Affairs and the Minister for Mineral Affairs gave their individual permissions for mining to take place in Mabola Protected Environment and did so in non-compliance with the provisions of the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act 57 of 2003 (NEM-PAA). This is the principal statute that safeguards, inter alia, protected environments. Drawing primarily on this non-compliance, Justice Davis, in the High Court, set both these approvals aside and instructed the Minister of Environmental Affairs to reconsider the application to undertake mining in the Mabola Protected Environment once the provisions of this statute had been complied with.

Following the Senior Court of Appeal's and the Constitutional Court's refusal of the mining company's request to appeal the Justice Davis decision, the Member of the Executive Committee (MEC), the provincial political head for the environment, in 2020, surprisingly, elevated his authority above that of the Courts and the responsibilities of the national Minister.

Furthermore, by using a discretionary clause in NEM-PAA in isolation to the other key provisions of the Act, the MEC amended, in what appears to be an arbitrary and capricious decision, the boundaries in a protected environment to circumvent a statutory prohibition of mining, as well as a series of orders issued by the High Court. Other than South Africa being seen to be pushed into the negative realm of 'protected area downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement' (PADDD), it is concluded that this country's protected areas, in the absence of the Courts, are vulnerable to prejudicial, politically based decision-making in favour of short-term parochial gains. It is further concluded that this potential outcome arose out of disregarding the public trust duties the MEC is obligated to apply.

Finally, it is recommended that the legislation providing for protected areas be amended to restrict the scope of discretionary clauses providing PADDD. Here the scope should be limited to the rare circumstance where the protected area cannot reasonably be avoided, and the development is unquestionably in the public's long-term best interest, and where the residual loss to biodiversity and the protected area estate is appropriately compensated or offset.

Acknowledgements

The supportive environments of Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife and the University of KwaZulu-Natal are acknowledged with thanks.

Disclaimer

The ideas, arguments and opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily represent those of Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife or the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Competing interests

None.

Authors' contributions

AB conceptualised, researched and wrote this article.

References

Alison, L., Smith, M.D., Eastman, O. & Rainbow, L., 2003, 'Toulmin's philosophy of argument and its relevance to offender profiling', Psychology, Crime & Law 9, 173-183, https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316031000116265. [ Links ]

Atmig, E., 2018, A critical review of the (potentially) negative impacts of current protected area policies on the nature conservation of forests in Turkey', Land Use Policy 70, 675684, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.10.054. [ Links ]

Blackmore, A., 2015, 'The relationship between the NEMA and the public trust doctrine: The importance of the NEMA principles in safeguarding South Africa's biodiversity', South African Journal of Environmental Law and Policy 20, 89-118. [ Links ]

Blackmore, A., 2018, 'The rediscovery of the trusteeship doctrine in South African environmental law and its significance in conserving biodiversity in South Africa', (Doctoral Thesis), University of Tilburg, Tilburg, The Netherlands. [ Links ]

Blackmore, A., 2020, 'Towards unpacking the theory behind, and a pragmatic approach to biodiversity offsets', Environmental Management 65, 88-97, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-019-01232-0. [ Links ]

Blackmore, A., 2022, 'Concurrent national and provincial legislative competence: rethinking the relationship between nature reserves and national parks', Submitted: Law, Democracy and Development. [ Links ]

CER, 2021, 'Centre for Environmental Rights - Statement on environmental MEC's decision to exclude properties from the Mabola Protected Environment to enable a new coal mine', Centre for Environmental Rights. URL: https://cer.org.za/news/statement-on-environmental-mecs-de-cision-to-exclude-properties-from-the-mabola-protect-ed-environment-to-enable-a-new-coal-mine (accessed 25 June 2021). [ Links ]

Cook, C.N., Valkan, R.S., Mascia, M.B. & McGeoch, M.A., 2017, 'Quantifying the extent of protected-area downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement in Australia', Conservation Biology 31, 1039-1052. [ Links ]

Coppa, S., Pronti, A., Massaro, G., Brundu, R., Camedda, A., Palazzo, L., Nobile, G., Pagliarino, E. & de Lucia, G.A., 2021, 'Fishery management in a marine protected area with compliance gaps: Socio-economic and biological insights as a first step on the path of sustainability', Journal of Environmental Management 280, 111754, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111754. [ Links ]

Davis, J., 2021, Mining and Environmental Justice Community Network of South Africa and Others v Uthaka Energy (PTY) Ltd (11761/2021) [2021] ZAGPPHC 195 (30 March 2021). [ Links ]

de Marques, A.A.B. & Peres, C.A., 2015, 'Pervasive legal threats to protected areas in Brazil', Oryx 49, 25-29, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605314000726. [ Links ]

De Vos, A., Clements, H.S., Biggs, D. & Cumming, G.S., 2019, 'The dynamics of proclaimed privately protected areas in South Africa over 83 years', Conservation Letters 12, https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12644. [ Links ]

Goosen, M. & Blackmore, A., 2019, 'Hitchhikers' guide to the legal context of protected area management plans in South Africa', Bothalia, a2399 49, 1-10, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v49i1.2399. [ Links ]

Hoffmann, S. & Beierkuhnlein, C., 2020, 'Climate change exposure and vulnerability of the global protected area estate from an international perspective', Diversity and Distribu-tons 26, 1496-1509, https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13136. [ Links ]

Lubbe, W.J., 2019, 'Mining in Chrissiesmeer wetland and state custodianship' (Doctoral Thesis), North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa. [ Links ]

Mascia, M.B. & Pailler, S., 2011, 'Protected area downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement (PADDD) and its conservation implications: PADDD and its implications', Conservation Letters 4, 9-20, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2010.00147.x. [ Links ]

MEJCON Judgment, 2018, Environmental Justice Community Network of South Africa and Others v Minister of Environmental Affairs and Others [2019] 1 All SA 491 (GP) (8 November 2018). [ Links ]

Mogale, PT. & Odeku, K.O., 2018, 'Transformative tourism legislation: an impetus for socioeconomic development in South Africa', African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 7, 1-16. [ Links ]

Prato, T. & Fagre, D.B., 2020. 'Protected Area Management' in: Wang, Y. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Natural Resources: Land. CRC Press, New York. [ Links ]

Qin, S., Golden Kroner, R.E., Cook, C., Tesfaw, A.T., Bray-brook, R., Rodriguez, C.M., Poelking, C. & Mascia, M.B., 2019, 'Protected area downgrading, downsizing, and de-gazettement as a threat to iconic protected areas', Conservation Biology 33, 1275-1285, https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13365. [ Links ]

Radeloff, V.C., Stewart, S.I., Hawbaker, T.J., Gimmi, U., Pid-geon, A.M., Flather, C.H., Hammer, R.B. & Helmers, D.P., 2010, 'Housing growth in and near United States protected areas limits their conservation value', Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 940-945, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0911131107. [ Links ]

RSA, 1989, Environment Conservation Act 73 of 1989. [ Links ]

RSA, 2003, National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act 57 of 2003. [ Links ]

SANParks, 2021, History of Vaalbos and Mokala National Park, Mokala National Park, URL: https://www.sanparks.org/parks/mokala/tourism/history.php (accessed 22 June 2021). [ Links ]

Shongwe Notice, 2021, 'Exclusion of part of Protected Environment (Farms Properties) As Part of an Existing Mabola Protected Environment in Terms of the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act 57 Of 2003 (As Amended)' Notice 2, Provincial Gazette 3225 of 15 January 2021. [ Links ]

Strydom, H.A. & King, N.D. (eds), 2009, Fuggle and Rabie's, Environmental Management in South Africa, Juta and Company Ltd. Cape Town. [ Links ]

Treves, A., Santiago-Ávila, F.J. & Lynn, W.S., 2019, 'Just preservation', Biological Conservation 229, 134-141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.11.018. [ Links ]

Van der Schyff, E., 2010, 'Unpacking the public trust doctrine: a journey into foreign territory', Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal 13122-159. [ Links ]

Watson, A., 1984, Sources of law, legal change, and ambiguity, University of Pennsylvania Pres, https://doi.org/10.9783/9781512821567. [ Links ]

Zurba, M., Stucker, D., Mwaura, G., Burlando, C., Rastogi, A., Dhyani, S. & Koss, R., 2020, 'Intergenerational dialogue, collaboration, learning, and decision-making in global environmental governance: the case of the IUCN intergenerational partnership for sustainability', Sustainability 12, 498, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020498. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr Andrew Blackmore; e-mail:

andy.blackmore@kznwildlife.com

Submitted: 16 August 2021

Accepted: 11 February 2022

Published: 18 March 2022

ORIGINAL RESEARCH, REVIEWS, STRATEGIES AND CASE STUDIES

A taxonomic revision of the Othonna auriculifolia Less. group (Asteraceae: Senecioneae: Othonninae)

Simon Luvo MagoswanaI, II; J. Stephen BoatwrightII; Anthony R. MageeIII, IV; John C. ManningIII, V

IDepartment of Biological and Agricultural Sciences, Sol Plaatje University, Private Bag X5008, Kimberley, 8300, South Africa

IIDepartment of Biodiversity & Conservation Biology, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag x17, Bellville, 7535, Cape Town, South Africa

IIICompton Herbarium, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, South Africa

IVDepartment of Botany and Plant Biotechnology, University of Johannesburg, P.O. Box 524, Auckland Park 2006, Johannesburg, South Africa

VResearch Centre for Plant Growth and Development, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

ABSTRACT

A taxonomic revision is presented for the two geophytic species of Othonna L. (Asteraceae: Senecioneae: Othonninae) distinguished by a condensed caudex without evident internodes. These species are morphologically and phylogenet-ically distinct from the remaining geophytic species. This account includes descriptions, complete nomenclature and typification, illustrations and geographical distribution. We recognise the following two species: O. auriculifolia with radiate capitula and mature pappus 3-25 mm long, and O. taraxacoides (DC.) Sch. Bip. with disciform capitula and mature pappus 3-8 mm long. Both species are vegetatively variable.

Keywords: geophytes; Othonna auriculifolia; O. taraxacoides; nomenclature; southern Africa; synonyms; succulent.

Introduction

The genus Othonna L. (Asteraceae, Senecioneae, Othonninae) comprises ± 90 species of succulent or sub-succulent perennial herbs or shrubs with more-or-less dorsiventrally flattened leaves and radiate or disciform capitula with female-sterile disc florets and female marginal florets with a beige or reddish pappus that is sometimes accrescent (Leistner 2001; Nordenstam 2007, 2012; Magoswana et al. 2019). The genus is concentrated in the Greater Cape Floris-tic Region of South Africa but extends into southern Namibia, southern Angola and Zimbabwe (Manning & Goldblatt 2012; Manning 2013; Magoswana et al. 2019, 2020).

The genus was last revised in its entirety by Harvey (1865) and is in urgent need of a modern taxonomic revision, although the preliminary floristic treatments by Manning and Goldblatt (2012) and Manning (2013), as well as the recent taxonomic revision of the geophytic species of the genus by Magoswana et al. (2019), constitute a valuable contribution to a complete revision of the genus in the Greater Cape Floristic Region.

Phylogenetic and biogeographic relationships within Othonna have not yet been adequately analysed, although the monophyly of the genus and its systematic position in the tribe Senecioneae have been established (Pelser et al. 2007). Preliminary molecular analyses (Magoswana 2017, unpubl.) retrieved the species with a tuberous rootstock and well-developed stem with cauline leaves in a clade comprising the majority of the geophytic species but excluding the remaining few geophytic species with a rosulate habit and condensed caudex.

The geophytic species with an aerial stem (the O. bul-bosa group) were recently monographed by Ma-goswana et al. (2019). The present account serves to complete the taxonomic treatment of the geophytic species of the genus Othonna, viz. with a rosulate habit (hereafter termed the O. auriculifolia group). Members of the O. auriculifolia group are deciduous geophytes with the crown at or near ground level and the annual stem highly condensed without evident internodes, thus appearing unbranched. The leaves and branches originate directly from the crown of the subterranean tuberous root, and the capitula are sub-scapose. The flowering capitula are erect or suberect, but the scapes become decumbent in fruit, with the capitula flexed upwards. In contrast, the O. bulbosa group have the crown or growth point of the subterranean rootstock with its renewal buds buried well below the soil surface, thus with the lower portion of the annual flowering stem underground and the exposed portion usually well developed. The fruiting peduncles remain erect in fruit (Magoswana et al. 2019).

We provide complete nomenclature and typifications, detailed descriptions and illustrations, and geographical distribution for both species of the O. auriculifolia group. Two species are recognised (O. auriculifolia Less. and O. taraxacoides (DC.) Sch. Bip.), and five names are reduced to synonymy.

Research methods and materials

Procedures

All relevant types were examined, as well as all collections from BOL, NBG, PRE and SAM (acronyms following Thiers 2022), the primary collections of southern African species. If the collecting number was not cited in the protologue but is present on the actual specimen then we have included this number in square brackets following the collector's name. Measurements of vegetative and reproductive structures were taken from specimens across the distribution range of each species to account for variation between the subpopulations. For leaf characters, only well-developed lower leaves were measured, as upper leaves may grade into bracts. Leaf width was measured at ± the middle of the leaf and leaf length did not include the petiole (if the species has a petiole).

The capitula were initially rehydrated for an hour in pre-boiled water and subsequently the involucral bracts and florets (ray and disc), anthers and stigmas were excised and studied under an Olympus SZ61 ste-reomicroscope and photographed using an Olympus SC30 camera with Olympus analysis getIT soft imaging

software (Informer Technologies, Inc.). Species localities are cited following the Quarter Degree Reference System (Edwards & Leistner 1971; Leistner & Morris 1976). Both species were also studied in the field in both the Northern and Western Cape provinces of South Africa over the winter and spring growing periods. During these field visits, photographs and detailed field notes were taken to capture any features lost when specimens were pressed, as well as information on habitat, flowering time and species associations.

Taxonomic treatment

Othonna L., Species Plantarum 2: 924. (1753). Type: O. coronopifolia L., lecto., designated by Green: 184 (1929).

Doria Thunb., Nova Genera Plantarum 12: 162. (1800). Type: Not designated.

Shrubs, subshrubs, or geophytes with underground tuber or herbs, ± succulent, crown and leaf axils cob-webbed. Leaves alternate, sometimes crowded basally, linear to ovate or obovate-spatulate or lyrate to pin-natisect, sub-succulent or leathery. Inflorescence terminal, pedunculate, capitula solitary or laxly cymose or paniculate. Capitula heterogamous, radiate or dis-ciform. Involucre campanulate, bracts uniseriate, free and adherent or connate up to 1/2, lanceolate to oblong, glabrous, green with scarious margins. Receptacle conical, punctate, glabrous, epaleate. Marginal florets female-fertile, usually yellow or sometimes white, rarely pink to mauve, filiform or ligulate; ovary glabrous or appressed-puberulous with white twin hairs; style branches with discrete lateral stigmatic areas, apices oblanceolate and shortly papillate. Cypselas ellipsoid to obovoid, 10-ribbed, dark brown, densely appressed-puberulous with myxogenic or non-myxog-enic white twin hairs, rarely glabrous; pappus bristles many, basally united, barbellate, persistent, beige or sometimes banded deep red. Disc florets functionally male, numerous, yellow or white to blue or pink, corolla tube funnel-shaped, 5-lobed; anthers obtuse at base with ovate apical appendages, filament collar balusteriform; ovary glabrous; style simple and cone-tipped, rarely with short branches but then without lateral stigmatic zones; pappus of± 10 barbellate bristles, sometimes reduced to one or two bristles and lacking in one species, united basally, white.

Distribution and ecology: ± 90 spp., largely restricted to the Greater Cape Floristic Region, with a few species in the eastern summer rainfall regions of South Africa and some extending to southern Angola and Zimbabwe; usually on sandy flats or rocky slopes, rarely seasonally damp sandy flats.

Key to the species of the Othonna auriculifolia group

1a. Shrubs or shrublets, succulents without tuberous rootstock.....remaining species of Othonna

1b. Geophytes with thickened or tuberous rootstock:

2a. Crown or growth point buried well below the soil surface, lower portion of annual stem underground and exposed portion usually well-developed; leaves emerge from the

aboveground portion of stem.............

.....O. bulbosa group (Magoswana et al. 2019)

2b. Crown at or near ground level, annual stem highly condensed without evident internodes, appearing unbranched; leaves originate directly from crown of subterranean tuberous root:

3a. Capitula disciform; pappus of marginal florets 3-8 mm long ... 1. O. taraxacoides (DC.) Sch. Bip.

3b. Capitula radiate; pappus of marginal (ray) florets 6-25 mm long.......2. O. auriculifolia Less.

Species treatments

1. Othonna taraxacoides (DC.) Sch. Bip. in Flora 27(2): 769 (1844). Doria taraxacoides DC., Prodromus 6: 471 (1838); Harv. in Flora Capensis. 3: 325 (1865). Type: South Africa, [Northern Cape]: 'in Africœ Capensis regione Gariepinâ' [Zwischen Zilwerfontein, Kooperbergen und Kaus in Drège (1843)], Drège [2881] [Sept.-Oct. 1838] (G-DC-G00473781, holo.- image!; K-000307012-imagel, P-0010014-imagel, iso.).

Deciduous geophyte, to 150 mm, stem subterranean, condensed, appearing unbranched, felted at crown; rootstock cylindrical to oblong. Leaves emergent or fully developed at flowering, crowded basally, erect to spreading, base narrowed and petiole-like, blade obovate-spatulate or rarely lyrate-pinnatifid, 10-35 x 5-25 mm, undulate-incised or crenate, glabrous, glaucous, petiole 5-50 mm long. Inflorescence cymose but appearing sub-scapose, one or more capitula per plant; scapes erect at flowering but decumbent in fruit, 20100 mm long, glabrous, ebracteate or sometimes with one or two bracteoles near base. Capitula disciform, involucre 10-20 mm diam., involucral bracts 13 or 14, lanceolate to elliptic, 5-15 x 2-4 mm, glabrous-peni-cillate. Marginal florets 13 or 14, corolla tube reduced, collar-like, 0.5-1.5 mm long, pale to deep yellow; ovary ellipsoid-ovoid; style bifid, greatly exserted, 4-6 mm long. Cypselas ellipsoid-ovoid, 2-4 x 1-2 mm, densely appressed-puberulous on ribs with white myxogen-ic twin hairs; pappus of numerous barbellate bristles, 3-8 mm long, beige or sometimes deep red. Disc florets numerous, yellow, corolla funnel-shaped, tube ± as long as limb, 0.5-2.0 mm long; filaments 1-2 mm long; ovary narrowly ellipsoid, 3-8 mm long, glabrous; style simple and cone-tipped; pappus of ± 10 barbel-late bristles united basally. Figure 1A, B.

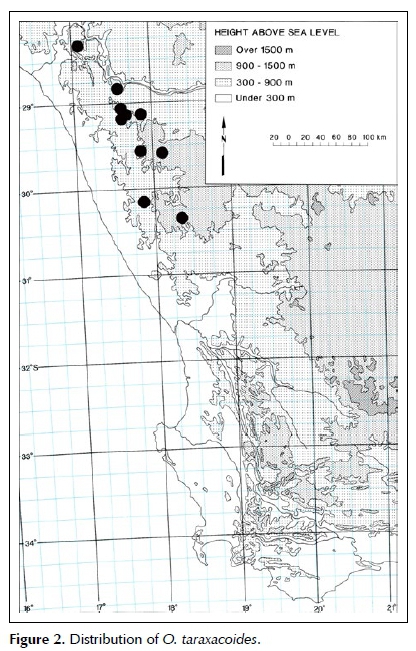

Distribution and ecology: a local endemic of the winter-rainfall region of Northern Cape, South Africa, distributed along the western escarpment from the Richtersveld to the Kamiesberg Mountains; usually in patches of gravelly quartz or sometimes in quartz outcrops, rarely on granite substrates. Flowering from July to September (Figure 2).

Diagnosis: Othonna taraxacoides is an acaulescent geo-phyte with obovate-spatulate or lyrate-pinnatifid leaves 10-35 mm long, and sub-scapose, disciform capitula (Figure 1A, B). The pappus of the cypselas is invariably short, 3-8 mm long.

Conservation status: The species is classified as Least Concern (LC) in the SANBI Red List of South African Plants (von Staden 2016).

Additional specimens examined

SOUTH AFRICA. Northern Cape: Vioolsdrif (2817): Richtersveld (-AC), Sept. 1933, Herre s.n. (NBG); base of Umdaus (-DC), 1 Aug. 1988, Williamson 3915 (NBG). Springbok (2917): Steinkopf, W of town along highway (-BA), 22 Aug. 2015, Deacon 4448 (NBG); 15 km N of Steinkopf (-BA), Sept. 1995, Williamson 5699 (NBG); 3 miles (5 km) W of Steinkopf (-BA), Aug. 1949, Hall s.n. (NBG); ± 10 km E of Jakkalswater (-BB), 8 Jul. 2008, Bruyns 11116 (NBG); 12 miles (19 km) E of Springbok (DB), 25 Aug. 1954, Barker 8382 (NBG). Gamoep (2918):

Kweekfontein (-CA), 2 Aug. 2000, Bruyns 8239 (NBG). Hondeklipbaai (3017): Kamieskroon (-BB), 4 Aug. 1952, Hall NBG 462/52 (NBG). Kamiesberg (3018): eastern Kamiesberg between Paulshoek and Platbakkies (-AD), 8 Sept. 2006, Snijman 2088 (NBG).

2. Othonna auriculifolia Less. in Linnaea 6: 93 (1831) [as 'auriculaefolial DC., Prodromus 6: 481 (1838); Harv. in Flora Capensis 3: 340 (1865). Type: South Africa, [?Northern Cape]: 'Roggeveld Majo', without date, Lichtenstein s.n. in Herb. Willdenow 16734 (B-W 167340 -10, holo.-image!). [Note: The name has until now been cited as 'Licht. ex Less.' based on Lessing's (1831) citation of the taxon as 'O. auriculaefolia Lichtenstein in herb. W. No. 16734' but we find no evidence that Lichtenstein used this name and interpret this entry as merely a citation of the type specimen.]

Othonna cyanoglossa DC., Prodromus 6: 481 (1838). Type: South Africa, [Western Cape]: 'Carro, Pietermeintjesfontein' [Matjiesfontein], June 1838, Drage [6078] (G-DC, holo.-mi-crofiche!, P-0004607-image!, syn.).

Othonna lactucifolia DC., Prodromus 6: 482 (1838) [as 'lactucœfolia']. Type: South Africa, [Eastern Cape]: 'in Africa Capensi ad Gra-af-Reynet' [Graaff-Reinet], Aug. 1838, Drège [6077] (G-DC, holo.-microfiche!, P-000460- image!, syn.).

Othonna picridioides DC., Prodromus 6: 482 (1838). Type: South Africa, 'in Africœ Capensi deserto Carro', Aug. 1838, Drège [6077] (G-DC-00498513, holo.-image!, P-0004605- image!, syn.).

Othonna auriculifolia var. arctotoides Harv. in Flora Capensis. 3: 340 (1865), syn. nov. Type: South Africa, 'Wolve River', May [?1842], Burke s.n., (K-0003037010, lecto., designated here; K-0003037009, isolecto.!). [Other original material: South Africa, without locality, Zeyher 992 (?TCD, not located, P-0004616- image!, syn.)].

[Othonna pimulina Schltr, nom. inval. ms., non. DC., Prodromus 6: 479 (1838): Associated specimens: South Africa, [Northern Cape] 'On-der-Bokkeveld, Oorlogkloof', 21 Aug. 1897, Schlechter 10962 (BR-0000008876379 image!, BR-0000008877390, K-306927 image!, PH-20047 image!, S-08-8797)].

Deciduous geophyte, to 250 mm, stem subterranean, condensed, appearing unbranched, felted at crown; rootstock cylindrical to turnip-shaped. Leaves emergent or fully developed at flowering, crowded basally, prostrate or spreading to sub-erect, base narrowed and petiole-like or evidently petiolate, blade narrowly oblong to obovate or suborbicular, flat or concave with lobes curled up, 20-120 x 5-25 mm, serrate or pinnatisect with quadrate to rounded lobes, or rarely entire, leathery to sub-succulent, usually glabrous, sometimes ciliate basally, or rarely sparsely to densely lanate or stiffly setose on both surfaces, glaucous or spotted or streaked with purple, petiole 10-80 mm long. Inflorescence cy-mose, appearing sub-scapose, one to several capitula per plant; scapes erect at flowering but decumbent in fruit, 20-180 mm long, glabrous or rarely sparsely lanate and glabrescent, bracteate basally with 1 or 2 lanceolate to elliptic or sometimes leaf-like bracts. Capitula radiate, involucre 10-30 mm diam., involucral bracts 11 to 14, lanceolate to elliptic, 7-15 x 2-5 mm, glabrous-penicil-late or rarely lanate. Marginal florets 11 to 14(17), corolla tube reduced, collar-like or cylindrical, 0.5-2.0 mm long, limb lanceolate to elliptic, 7-15 mm long, unicolorous or discolorous, pale to deep yellow above, usually flushed purple or blue beneath; ovary ellipsoid to obovoid; style bifid, included, branching below mouth of tube. Cypselas ellipsoid-ovoid, 2-6 x 1-3 mm, densely ap-pressed-puberulous on ribs with white myxogenic twin hairs; pappus of numerous barbellate bristles, 3-25 mm long, united basally, beige. Disc florets numerous, yellow or lobes sometimes mauve to purple, corolla funnel-shaped, tube ± as long as limb, 0.5-2.0 mm long, lobes lanceolate to ovate, 0.5-1.0 mm long; filaments 1-2 mm long; ovary narrowly ellipsoid, 2-6 mm long, glabrous; style simple and cone-tipped; pappus of ± 10 barbellate bristles united basally. Figure 1C-F.

Distribution and ecology: a well-collected species that is widely distributed through the drier interior parts of southwestern and western South Africa, where it is best known from the Hantam and Roggeveld in Northern Cape but as far north as Springbok, extending along the drainage basin of the Orange River into Bushmanland, and south through the interior Cape Floristic Region of Western Cape to Willowmore in Eastern Cape, with scattered records from the interior parts of Eastern Cape and southern Free State; occurring on a wide variety of substrates, usually on shale flats in open karroid scrub, rarely on sandy flats or on sandstone rock sheets at high altitudes in arid fynbos. Flowering from May to September (rarely early October at high altitude) (Figure 4).

Diagnosis: Othonna auriculifolia is an acaulescent geo-phyte with entire or serrate to pinnatisect leaves and scapose, radiate capitula with 11 to 14 involucral bracts and often discolorous ray florets, and disc florets sometimes with mauve to purple lobes. The species is vege-tatively variable, the leaves ranging from narrowly oblong to obovate and pinnatisect to serrate or sometimes entire and suborbicular (Figures 1C-F & 4). The leaves of O. auriculifolia are usually glabrous but a few populations between Clanwilliam and Calvinia [Coetzee CJ1 (NBG), Koopman DK049 (NBG) and Schlechter 10836 (BOL)] are distinctive in having the leaves densely covered with long, tangled hairs. We considered the possibility that these populations represent a separate species but additional populations from Worcester [Tyson s.n. (SAM)] are sparsely lanate-glabrescent and thus intermediate between the glabrous and densely hairy plants, and populations on the Hex River Mountains have the leaves stiffly setose. We therefore conclude that Othonna auriculifolia is also variable in leaf vestiture.

Candolle (1838) treated a number of these vegetative variants as distinct species. Othonna cyanoglossa DC., based on a collection from Matjiesfontein in Western Cape, was distinguished by ovate to sub-rotund leaves with sinuate-dentate margins, and scapes ± as long as the leaves; O. lactucifolia DC., from Graaff-Reinet in Eastern Cape, by ovate leaves with sinuate, mucro-nate-dentate margins and peduncles as long as the leaves; and O. picridioides DC. from the 'Karoo' by pin-natifid leaves with subrotund lobes with serrate-dentate margins, and peduncles shorter than the leaves. These taxa were synonymised by Harvey (1865), a decision that is supported by our observations of the ± continuous variation in leaf shape among collections and sometimes even individual plants, as well as observations in the field. Harvey (1865), however, segregated plants from Wolve River near Calvinia in

Northern Cape with petiolate, cuneate-obovate leaves with entire or repand, or sometimes variably incised or pinnatifid margins, as var. arctotoides Harv. Specimens matching this form occur throughout the range of the species among more typical individuals, and evidently represent extreme or juvenile variants, and we do not recognise the variety.

Conservation status: The species is classified as Least Concern (LC) in the SANBI Red List of South African Plants (Raimondo et al. 2009).

Additional specimens examined

SOUTH AFRICA. Free State: Jagersfontein (2925): Fauresmith Botanical Reserve (-CB), 1 Sept. 1925, Smith 398 (PRE); 2 Sept., 1925, Smith 418 (PRE); 27 Jul. 1930, Potter 2022 (PRE); 1 Sept. 1925, Pole-Evans and Smith 841 (PRE).

Northern Cape: Griekwastad (2823): Griquatown (-CC), Jun. 1895, Marloth s.n. (PRE); Jul. 1914 (PRE). Kimberley (2824): 7 miles [11 km] NE of Kimberley on Samaria Road (-DA), 24 Aug. 1961, Leistner and Joynt 2649 (PRE); 3 miles (5 km) N of Kimberley (-DA), 17 Jun. 1959, Leistner 1421 (PRE). Springbok (2917): Hester Malan Nature Reserve (-DB), 1 Jul. 1975, Rosch and Le Roux 1167 (PRE). Pofadder (2919): Farm Gannapoort, 26 miles [42 km] east of Pofadder (-BC), 21 May 1961, Schlieben 8952;

Leistner 2470 (PRE). Prieska (2922): Prieska (-BC), Jun.

1935, Bryant 1130 (PRE). Calvinia (3119): Bokkeveld, Farm Meulsteenvlei (-AC), 13 Sept. 1926, Marloth 12945

(PRE); Nieuwoudtville (-AC), 11 May 1983, Perry and

Snijman 2093 (NBG); 15 Jun. 1983, Perry and Snijman 2112 (NBG, PRE); 8 Sept. 1983, Perry and Snijman 2356 (PRE); 15 Sept. 2000, Koekemoer and Funk 1949 (PRE); ± 3 km S of Nieuwoudtville (-AC), 4 Jun. 2010, Helme 6584 (NBG); Glen Ridge Farm, Nieuwoudtville (-AC), 19 Jul. 1962, Barker s.n. (NBG); Nieuwoudtville, Hantam National Botanical Gardens (-AC), 13 May 2015, Coetzee CJ1 (NBG); 23 May 2016, Koopman DK049 (NBG); Willem's River (-AC), without date, Leipoldt 754 (SAM); Karigaboschfontein S of Calvinia (-AD), 20 Aug. 1975, Thompson 2473 (NBG); foot of Hantam Mountains (BC), Jul. 1948, Lewis 2586 (SAM); Hantamsberg, summit of plateau above Ambralshoek (-BD), 18 Aug. 1975, Thompson 2336, 2338 (NBG); Menzieskraal 816, 35 km SE of Nieuwoudtville on Botterkloof Road (-CA), 11 Aug. 2009, Helme 6450 (NBG); Nieuwoudtville Nature Reserve (-CA), 8 Sept. 1983, Perry and Snijman 2356 (NBG); 7 Aug. 1986, Steiner 1243 (NBG); Kareeboomfontein (-DA), 5 Sept. 1974, Hanekom 2398 (PRE); Riepjoeni [Rebunie] Mountains (-DA), Aug. 1921, Marloth 10301 (PRE). Victoria West (3123): Groot Boschmanspoort, NE of Victoria West (-AC), 14 May 1976, Thompson 3078 (NBG). Sutherland (3220): Roggeveld, Soekop (-AA), 8 Aug. 2006, Rösch 461 (NBG); Voëlfontein Farm (-AA), 10 May 1969, Hall 219A (NBG); Tankwa Karoo National Park, top of Gannaga Pass (-AA), 5 Aug. 2006, Koeke- moer 3205, 3210, 3213 (PRE); Tankwa Karoo National Park, between Quaggasfontein and Uitkyk (-AD), 7 Sept. 2013, Koekemoer 4423 (PRE); Tankwa Karoo, Quaggasfontein (-AD), 27 Sept. 1998, Desmet 1856 (NBG); Koedoesbergpas on Ceres-Sutherland Road (-CC), 20 May 1976, Hugo 398 (NBG); between Laingsburg and Sutherland near Komsberg Pass (-DB), 3 Jul. 1983, Vlok 609 (NBG, PRE); 3 km W of top of Komsberg Pass (-DB), 19 Jul. 2006, Bruyns 10506 (NBG).

Western Cape: Vanrhynsdorp (3118): near Vanrhyns-dorp (-DA), 6 May 1965, Barker 10193 (NBG). Wuppertal (3219): Pakhuisberg, 17 km from Clanwilliam on road to Pakhuis (-AA), 25 Aug. 1995, Rodriguez-Oubina and Cruces 2101 (PRE); Pakhuis, Heuningvlei (-AA), 24 Jul. 1983, Hockey 1 (NBG); Farm Lamkraal (-AA), 14 Aug. 1897, Schlechter 10836 [2 sheets] (BOL); top of plateau, Algeria (-AC), 3 Aug. 1937, Martin NBG 1294 (NBG); Middelberg hut (-AC), Jun. 1980, Hugo 2372 (NBG); SE slopes of Bloukop (-CB), 13 Sept. 2002, Burgoyne 9340 (PRE); foothills of Bloukop on the Luiperdskloof 4 x 4 route (-CB), 11 Sept. 2002, Koekemoer 2411 (PRE); 13 Sept. 2002, Koekemoer 2425, 2430 (PRE); Breekkrans (-CB), 22 Jun. 1984, Taylor 10961 (NBG); Gonnafontein (-CB), 8 Jul. 2000, Pond UP98 (NBG); Koue Bokkeveld (-CC), 13 Aug. 1979, Miros s.n. (NBG); Groenfontein, on road to Kaggakamma (-DC), 10 Jul. 1991, Van Zyl 4205 (PRE); Knolfontein, 60 km NE of Ceres (-DC), 14 May 2008, Jardine and Jardine 870 (NBG); 26 Aug. 2012, Jar-dine 1818 (NBG); 29 Jul. 2009, Jardine and Jardine 1153 (NBG); 6 Sept. 2011, Jardine 1593 (NBG); 17 Aug. 2011, Jardine 1573 (NBG); 15 Jul. 2005, Jardine and Jardine 17 (NBG); 12 Sept. 2008, Jardine and Jardine 928 (NBG); 19 Jun. 2006, Jardine and Jardine 314 (NBG), 26 Jul. 2010, Jardine 1489, 1490 (NBG); 18 May 2010, Jardine 1494, 1495, 1496, 1497 (NBG); Groenfontein, Zeekoegat 137, W of Rietriver (-DC), 16 Jun. 2000, Stobie 4 (NBG). Beaufort West (3222): Courland's Kloof, Nelspoort (-DB), Jul. 1907, Pearson 1486 (SAM). Worcester (3319): Matroosberg summit (-AC), 26 Sept. 1981, Kotze 100 (NBG); Mostersthoek (-AD), 2 Aug. 1926, Stokoe 697 (PRE); Doornriver (-AD), 9 Jul. 1991, Van Zyl 4197 (NBG); Farm Tweeriviere along the Ceres-Patatsrivier Road (-BB), 25 Jun. 1979, Van Breda 4463 (PRE); Karrooport (-BC), Aug. 1919, Marloth 9010 (PRE); 27 Jul. 1941, Compton 11159 (NBG); NW of Worcester, 16 May 1948, Bayer 4142 (NBG); Hex River Mountains, N slopes of Rooiberg (-BC),

19 Aug. 1999, Oliver 11310 (NBG); 1.5 miles [2.4 km] W of Verkeerdevlei dam (-BD), 17 Jun. 1965, Acocks 23665 (PRE); Verkeerdevlei (-BD), 13 Jun. 1975, Durand 27 (PRE); 12 Jul. 1954, Barker 8287 (NBG); Matroosberg (-BD), 30 Sept. 1928, Andrea 1157 (PRE); Zach-ariashoek, La Motte Forest Station (-CC), 3 Jun. 1982, Viviers 386 (PRE); near Nuy (-DA), 8 Jul. 1970, Barker 10702 (NBG). Montagu (3320): Tweedside (-AB), 1 Jun. 1925, Marloth 12058, 12073 (PRE); Pieter Meintjies (AD), 28 Apr. 1946, Barker 4023 (NBG); Klein Roggeveld (-BA), 8 Jul. 1938, Compton 7275 (NBG); Matjiesfontein, Whitehill (-BA), 7 Aug. 1933, Humbert 9726; 7 Sept. 1983, van Zyl 3567 (PRE); Whitehill (-BA), 7 Jul. 1941, Compton 10881 (NBG); 17 Aug. 1942, Compton 13385 (NBG); Waboomsberg main kloof E of Brakleegte (-CB), 14 Jul. 1994, Oliver 10484 (NBG); Touws River (-DA), Jul. 1903, Marloth 3230 (PRE); Fonteinskloof (-DC), 14 Jul. 1954, Rycroft 1590 (NBG); Barrydale (-DC), 5 Aug. 1949, Barker 5463 (NBG); 6 Aug. 1949, Barker 5400 (NBG). Ladismith (3321): N of Klein Swartberg (-AD), 24 Jul. 1957, Warts 1508 (NBG); Gamka Mountain (-BC),

20 Aug. 1975, Boshoff P223 (NBG); Witteberg (-CA), 11

May 1941, Compton 10813 (NBG); top of Witteberge,

Matjiesfontein (-CA), 29 Sept. 1983, Van Zyl3566 (NBG);

Derde River (-CD), 8 Jun. 1925, Muir 3624 (PRE); N of Garcia's Pass (-CC), Sept. 1923, Muir 2951 (PRE); Farm Phisante Kraal 166, top of Witteberg (-CC), 9 Aug. 1988, Pool 57 (NBG); ± 1 km along road from Dwars in die weg to Rietkuil (-DA), 5 Aug. 2015, Manning and Magoswa-na 3507 (NBG); Gamka Mountain Reserve, Bakenskop (-DB), 16 Apr. 1998, Rourke 2127 (NBG, PRE); Gamka Mountains between Calitzdorp and Oudtshoorn (-DB), 22 Jul. 1980, Taylor 10209 (PRE); Gamka Mountain Reserve (-DB), 16 Apr. 1998, Rourke 2127 (NBG); Mountain Zebra Reserve, between Calitzdorp and Oudtshoorn (-DB), 22 Jul. 1980, Taylor 10209 (NBG). Oudtshoorn (3322): Farm Frisgewaagd, Swartberg Mountains (-AD), Jun. 1986, Vlok 1486 (PRE); Vrolikheid (-BC), Jul. 1976, Merwe 2837 (PRE); Oudtshoorn commonage (-CA), Jul. 1925, Marloth 12180 (PRE); Farm Kleinvlakte, 10 miles [16 km] from Barrydale (-DC), 3 Jun. 1974, Van Breda 4240 (PRE). Bredasdorp (3420): Rietvallei, on boundary of four farms and Suurbraak (-BA), 17 Aug. 2008, Von Witt CR3209 (NBG).

Eastern Cape: Lady Grey (3027): Fontein's Kloof, near Driefontein (-CD), 14 Jul. 1954, Lewis 4497 (SAM). Victoria West (3123): Murraysberg (-DD), Apr. 1879, Tyson 390 (PRE). Steynsburg (3125): Conway farm (-CB), Aug. 1899, Gilfillan 5552 (PRE). Queenstown (3126): N slopes of Andriesberg (-DA), 23 May 1899, Galpin 2611 (PRE). Cradock (3225): National Bergkwagga Park [Mountain Zebra National Park] (-AD), 5 May 1963, Liebenberg 7214 (PRE). Willowmore (3323): Uniondale, Vettevlei (-CA), 8 Jul. 1935, Markötters.n. (NBG).

Acknowledgements

We thank the curators and staff of the herbaria cited; CapeNature (permit number: CN35-28-15073) and the Northern Cape Province Department of Environmental and Nature Conservation for providing permits (permit number: FLORA 0048/2017). This work is based on research supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant Number 118597) awarded through the Foundational Biodiversity Information Programme (FBIP), a joint initiative of the Department of Science and Technology (DST) and the South African National Biodiversity Institute. Additional funding was provided by Elizabeth Parker of Elandsberg. Nick Helme, Eugene Marinus and Frik Linde are acknowledged for the use of their photographs. Rose Smuts is also thanked for field assistance. Robyn Powell (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew) is thanked for locating the type material of Othonna auriculifolia var. arctotoides. We thank the two anonymous reviewers who helped improve the quality of this manuscript.

Author contributions

S.L.M. and J.M. were the project leaders, A.M. and J.S.B. made conceptual contributions.

References

Candolle, A.P de, 1837 [1838], 'Compositae', Prodromus Systematis Naturalis Regni Regetabilis, vol. 6, Treuttel et Würtz, Paris. [ Links ]

Edwards, D. & Leistner, O.A., 1971, 'A degree reference system for citing biological records in southern Africa', Mitteilungen des Botanische Staatssammlung München 10, 501-509. [ Links ]

Harvey, W.H., 1865. 'Compositae', in Harvey, W.H. & Sonder O.W. (eds.), Flora Capensis 3, 44-530, Hodges, Smith & Co., Dublin. [ Links ]

Leistner, O.A. & Morris, J.M., 1976, 'Southern African place names', Annals of the Cape Provincial Museums 12, 1-565. [ Links ]

Leistner, O.A., 2001, 'Seed plants of southern Africa: families and genera', Strelitzia 10, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Lessing, C.F., 1832, 'Synopsis Generum Compositarum Earum-que Dispositionis Novae Tentamen Monographis Multarum Capensium Interjects', Sumtibus Duncken et Humblotii, Berlin, p. 473. [ Links ]

Linnaeus, C., 1753, 'Species plantarum'. Salve, Stockholm. [ Links ]

Magoswana, S.L., 2017, 'Systematics of geophytic Othonna (Senecioneae, Othonninae)', MSc thesis, University of the Western Cape, Bellville. [ Links ]

Magoswana, S.L., Boatwright, J.S., Magee, A.R. & Manning, J.C., 2019, 'A taxonomic revision of the Othonna bulbosa group (Asteraceae: Senecioneae: Othonninae)', Annals of the Missouri Botanical Gardens 104, 515-562, http://doi.org/10.3417/2019340. [ Links ]

Magoswana, S.L., Boatwright, J.S., Magee, A.R. & Manning, J.C., 2020, 'Othonna cerarioides (Asteraceae: Othonninae), a new species from Namaqualand, South Africa', Nordic Journal of Botany 38(3), 1-6, http://doi.org/10.1111/njb.02588. [ Links ]

Manning, J.C. & Goldblatt, P., 2012, 'Plants of the Greater Cape Floristic Region 1: the Core Cape flora', Strelitzia 29, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Manning, J.C., 2013, 'Othonna', in Snijman, D. (ed.), 'Plants of the Greater Cape Floristic Region 2: the extra Cape Flora'. Strelitzia 30, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Nordenstam, B., 2007, 'Tribe Senecioneae', in Kadereit, J.W. & Jeffrey, C. (eds.), 'Flowering Plants. Eudicots. Asterales', in Kubitzki, J. (ed.), The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants 8, 208-241, Springer, Berlin. [ Links ]

Nordenstam, B., 2012, 'Crassothonna B. Nord., a new African genus of succulent Compositae-Senecioneae', Com-positae Newsletter 50, 70-77. [ Links ]

Pelser, P.B., Nordenstam, B., Kadereit J.W. & Watson, L.E., 2007, 'An ITS phylogeny of tribe Senecioneae (Asteraceae) and a new delimitation of Senecio L.', Taxon 56, 1077-1104, https://doi.org/10.2307/25065905. [ Links ]

Raimondo, D., von Staden, L., Foden, W., Victor, J.E., Helme, N.A., Turner, R.C., Kamundi, D.A. and Manyama, P.A. 2009, 'Red List of South African Plants', Strelitzia 25. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Schultz, C.H., 1844, 'Enumeratio Compositarum a cl. Dr. Krauss annis 1838-40 in Capite bonae spei et ad portum Natalensem lectarum', Flora 27, 704-768. [ Links ]

Thiers, B., 2022, 'Index Herbariorum: A global directory of public herbaria and associated staff: New York Botanical Garden's Virtual Herbarium', Available online: http://sweetgum.nybg.org/ih/). [ Links ]

Thunberg, C.P, 1800. 'Nova genera plantarum' 12, 162. Ed-man, Uppsala. [ Links ]

von Staden, L. 2016, 'Othonna taraxacoides (DC.) Sch.Bip.' National Assessment: Red List of South African Plants version 2020.1. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Simon Luvo Magoswana

e-mail: luvo.magoswana@spu.ac.za

Submitted: 3 June 2021

Accepted: 11 February 2022

Published: 18 March 2022

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Ecological factors determining the distribution patterns of Cyrtanthus nutans R.A.Dyer (Amaryllidaceae) in northwestern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Lynne M. RuddleI; Erika A. van ZylII; Jorrie JordaanIII

IP.O. Box 72512, Lynnwood Ridge, Pretoria, 0040

IIGrass and Forage Scientific Research Services, Dundee Research Station, KwaZulu-Natal, Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, P.O. Box 626, Dundee, 3000

IIIP.O. Box 788, Modimolle, 0510

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Cyrtanthus nutans R.A.Dyer is a range-restricted species occurring in northwestern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa and in Eswatini, and is currently classified as Vulnerable in accordance with the IUCN criteria. Land transformation and disturbance of natural habitats have resulted in an ever-increasing fragmentation of the species' range.

OBJECTIVES: This manuscript provides a description of some of the abiotic and biotic factors associated with the remaining natural populations of C. nutans in the Sour Sandveld and Moist Tall Grassland Bioresource Groups of northwestern KwaZulu-Natal

METHODS: An investigation was conducted in the northwestern KwaZulu-Natal region to determine the effect that key ecological and anthropological determinants have in influencing the distribution and survival of the species. Data collected included sites of occurrence, estimated population numbers, elevation, ecological factors (soils/geology, climate, veld composition), and human/animal activities.

RESULTS: The northwestern KwaZulu-Natal C. nutans populations were found to occur primarily in untransformed veld within the Moist Tall Grassveld, Dry Highland Sourveld and Sour Sandveld Bioresource Groups. It occurs largely on gradients of < 10% on mid- to lower terrain slopes and predominantly within an altitude range of between 1 100 and 1 300 m a.m.s.l.

CONCLUSION: C. nutans occurs in a narrow altitudinal range and has a preference for soils with high nitrogen and organic carbon and low phosphorus and acidity levels.

Keywords: autecology, Dundee fire lily, plant species distribution.

Introduction

Almost a quarter of the ± 20 700 vascular plant taxa indigenous to the Republic of South Africa are threatened with extinction or are of conservation concern (Von Staden et al. 2013; SANBI 2020). Almost all ecosystems in southern Africa have been modified or transformed by human activity (Macdonald 1989), and southern African plant diversity faces several pressures and multiple threats from both sustainable and unsustainable agricultural practices, urbanisation and mining in addition to the uncontrolled spread of alien invasive plants and illegal plant harvesting (Macdonald 1989; Scott-Shaw 1999). The east coast province of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) is home to 5 261 vascular plant taxa, of which almost 14% are categorised as threatened or of conservation concern (SANBI 2020).

Cyrtanthus nutans R.A.Dyer (Amaryllidaceae), is a deciduous geophyte that reproduces vegetatively or by seed after a short spring flowering period. It is currently classified as Vulnerable B1ab(iii), according to the National Red List categories, with an extent of occurrence (EOO) of 6 067 km2 in only four locations (SANBI 2020).

The first documentation of C. nutans in KZN was by Dr L.E. Codd in 1952, who collected the plants for cultivation. He found the plants and described them as abundant in an area of approximately 8 km2 in the Vants Drift area (latitude 28° 10'S and longitude 30° 31'E), near Dundee. Two years later, Dyer (1954) formally recorded the presence of the plants and taxonomical-ly described the species. The area of occurrence fell within what is now known as the Umzinyathi District Municipality (DM), and were subsequently found in a small area in the adjoining Uthukela DM. This comprises the study area, which extends over some 1 450 km2.

Ten years later the species was located in Eswatini [Swaziland], on the hills around Mbabane above the Komati River, Piggs Peak, by Gordon McNeil (McNeil 1967; Reid & Dyer 1984) and has recently been documented as occurring in the mountains above Barberton, Mpum-alanga, South Africa (SANBI 2020).

Distribution patterns of C. nutans were briefly described in the Dundee area in 2011 (Scott-Shaw 2011: pers. comm.). Indications were that the species was not as abundant as described in the 1952 Dyer report. The probable causes or factors for a reduction in population are not known. Furthermore, in 2006, the unsuccessful translocation of a C. nutans population from a housing development project in the Umzinyathi DM emphasised the lack of information on the specific habitat preferences of the plants. Following these events, informal observations of C. nutans were noted, which eventually led to annual Spring recordings of flowering plants, from 2012 onwards, of distribution sites in Dundee, KZN and surrounding areas. A formal reevaluation of the Dundee C. nutans distribution was undertaken from 2014 onwards, which form the current study (Ruddle 2018).

Materials and methods

Study area description

The study area is characterised by relatively high elevations, sandy soils, sourveld grasslands and sparsely scattered paperbark thorn trees (Vachellia sieberiana). The Bioresource Groups (BRG) that occur in the area are Dry Highland Sourveld, Moist Tall Grassveld, Sour Sandveld and Mixed Thornveld (Camp 1999). The area is typically a summer rainfall region (October to March) with a long-term mean annual rainfall of 749 mm annum-1.

Long term annual rainfall records for the period 1968 to 2016 indicated that the highest and lowest annual recorded rainfall during this period occurred during 2012/2013 and 2014/2015 respectively and occurred during the study period (Agrometeorology 2019).

Data collection

Over a four-year period (2013-2016) during the spring months of September to mid-December, which covers the flowering period of C. nutans, areas within the district municipalities were randomly traversed by motor vehicle and on foot, identifying sites of occurrence. The number of flowering plants, latitude/longitude co-ordinates, altitude and gradient were recorded, and the presence or absence of fire/herbivores or human activities and land use were documented.

Vegetation species composition surveys were carried out at C. nutans sites according to a method described by Camp and Hardy (1999). A 50 χ 50 m square was marked at each site. Within the square, a W-shaped path was traversed, using a sharp stick, of approximately 1.2 m in length, 50 spike-point observations were made. The nearest grass species to the point was identified and recorded.

Soil samples were taken at sites on the basis that no evidence of historical disturbance was noted but were a good representative of the known geology of the area. Using a Dutch auger, samples were taken at a depth of 0-30 cm (Sample A: topsoil, excluding organic material) and depth 30-60 cm (Sample B: sub-soil). The chemical soil analyses were carried out in accordance with standard practices (Manson & Roberts 2001) at the Cedara Feed and Soil Laboratory of the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Agriculture, Environmental Affairs and Rural Development, which is an accredited laboratory.

Data analysis

Co-ordinates of sites of C. nutans occurrence were mapped onto a 1:50 000 digital topographical map and Bioresource Group vegetation map (Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife 2009). The condition of the herbaceous component survey per site was compared with that of a benchmark site to calculate a veld condition per site (Camp & Hardy, 1999). A benchmark site is the most productive of its kind in terms of the highest possible sustained animal production within the Bioresource Groups (BRG) and are pre-described by Camp and Hardy (1999). Climatic data for the study were sourced from the Agricultural Research Council (ARC) (Agrome-teorology 2019) weather station, based at the Dundee Research Station (Comp 30109).

Results and discussion

Sites of occurrence

During the study period, a total of 27 sites, where C. nutans plants occurred, were found over an area of approximately 1 450 km2. In Umzinyathi DM, plants were only located in two of the four Local Municipalities (LM); namely, Endumeni LM and Msinga LM. In Uthukela they were only located in the adjoining Indaka LM near Wasbank. The sites of occurrence were classified into five main groups, according to population densities and basic land use type; namely, Area 1 - urban; Area 2 -semi-urban/industrial/agriculture; Area 3 - semi-urban and agriculture; Area 4 - commercial agriculture; and Area 5 - mixed wildlife/cattle rangeland (Figure 1).

Description of sites of occurrence

Topography

The C. nutans populations were recorded at an altitude range of between 1 031 and 1 459 m a.m.s.l. in an area extending over 1 450 km2. The great majority of plants (97.98%) occurred within the 1 100-1 300 m altitude range (Figure 2).

Slopes and gradients

Most of the C. nutans populations were found on relatively flat grassveld areas with gradients of less than 15° overall (mid- to foot slopes); 75% of the C. nutans populations were found on gradients of less than 10% with no preference for a particular facing slope.

Gradients play a fundamental role in water drainage and the subsequent formation of soils and nutrient deposits on the lower slopes (Gordon 2017; pers. com.). The soil fertility environment of C. nutans is not currently known, however established populations at certain sites may indicate its favourability for the species. Soil acidity levels, clay percentages and nutrient levels based on the soil sample readings, provide an indication of a favourable soil environment (Gordon 2017; pers. com.).

Geological and soil data

Soil sampling was undertaken in four of the five main areas indicated in Figure 1. The dominant parent rock at the sites was dolerite, with only two sites underlain with shale or sandstone (Table 1). Nitrogen levels were high (>0.16%) in all except one site in Area 3, where subsoil nitrogen levels were too low to measure due to low organic carbon percentages. Low acidity (< 10% acid saturation), high organic carbon percentages (>1.8%) and tolerance of a wide range of textures (15 to 50% clay) and low phosphorous levels appears to be adequate for C. nutans plants.

Vegetation data

Cyrtanthus nutans were primarily found within the Moist Tall Grassveld (20% of plants counted) and Sour Sandveld (79% of plants counted) with minimal occurrence in Dry Highland Sourveld (1% of plants counted) (Figure 3).

The veld condition assessment for Area 5 was not conducted as further access to the property was unattainable. No clear picture arises from veld conditions compared with number of flowering plants counted since

C. nutans was found in areas where veld conditions ranged from relatively low (22%) to relatively high (one site indicated a veld condition of 100%). A high percentage of sites (40-100%) had been burnt or grazed prior to plant emergence (Table 2).

Population size

Most of the flowering plants were located in Area 3 (53%) and Area 2 (25%), with fewer populations in Area 1 (14%), Area 4 (7%) and Area 5 (1%). As the study progressed, fewer new sites plant populations and flowering plants were identified (Table 3).

Anthropological influences

Large scale fragmentation of an already restricted range was evident with the distribution of C. nutans. Population sites were distributed primarily on the periphery of arable land, in natural veld situated outside of fenced agricultural properties, along road reserves that had not been graded/cleared, and in the narrow band of railway reserves; these areas were not conducive to land transformation. Areas utilised for low intensity grazing over long-term periods were predominantly well populated with C. nutans. Only sites situated in Areas 1 and 2 (urban and semi-urban) indicated some form of human activity in terms of pedestrian and vehicular thoroughfares, dumping of building materials, graded road reserves and the subsequent damage to plants and habitat fragmentation resulting in smaller isolated pockets of plants.

Conclusions

Abiotic and biotic factors associated with the geographical distribution of C. nutans in the Sour Sand-veld and Moist Tall Grassland Bioresource Groups of northwestern KwaZulu-Natal have been documented.

The species occurs within a narrow altitudinal range on relatively flat grasslands on predominantly doler-ite parent rock in soils with moderate nitrogen and organic material, and low phosphorus and acidity levels. Land transformation in the Dundee area has resulted in the fragmentation of C. nutans populations

into smaller isolated pockets. According to Von Staden (2013), the expansion of both urban and agricultural areas in the Dundee area has resulted in a 9% loss of habitat in the past 24 years and C. nutans is threatened by habitat degradation due to crop cultivation and overgrazing.

References

Agrometeorology (ARC-ISCW Agro-Climatology Data Base), 2019, ARC-Institute for Soil, Climate and Water, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Camp, K.G.T. & Hardy, M.B., 1999, In: Hardy, M.B., & Hurt, C.R., 1999, Veld in KwaZulu-Natal, Agricultural Production Guidelines for KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg: KwaZulu-Natal Department of Agriculture. [ Links ]

Camp, K.G.T., 1999, A bioresource classification for KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. [ Links ]

Dyer, R.A., 1954, Cyrtanthus. The Flowering Plants of Africa, 30: t 1182. [ Links ]

Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, 2009, Bioresource topography maps, Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Macdonald, I.A.W., 1989, Man's role in changing the face of southern Africa, in Biotic Diversity in Southern Africa: Concepts and Conservation. Oxford University Press, Cape Town, pp. 51-72. [ Links ]

Manson, A.D. & Roberts, V.G., 2000, Analytical methods used by the soil fertility and analytical services section. Republic of South Africa, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

McNeil, G., 1967, 'A brief introduction to Cyrtanthus', Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society: XCII (4), 180183. [ Links ]

Reid, C., Dyer, R.A. & American Plant Life Society (La Jolla), 1984, 'A review of the southern African species of Cyrtan-thus', American Plant Life Society. [ Links ]

Ruddle, L.M., 2018, Ecological characterisation and effects of fire and grazing on Cyrtanthus nutans (R.A.Dyer) in North-Western Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa, Masters dissertation. [ Links ]

SANBI, 2020, Statistics: Red List of South African Plants version 2020.1, available at http://www.redlist.sanbi.org (Accessed: 13 August 2020). [ Links ]

Scott-Shaw, R., 1999, Rare and threatened plants of KwaZulu-Natal and neighbouring regions, KwaZulu-Natal Nature Conservation Service. [ Links ]

Von Staden, L., Raimondo, D. & Dayaram, A., 2013, Taxo-nomic research priorities for the conservation of the South African flora, South African Journal of Science, 109(3-4), 1-10, https://doi.org/10.1590/sajs.2013/1182. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Lynne M. Ruddle

e-mail: lynne.ruddle1@gmail.com

Submitted: 19 May 2021

Accepted: 7 December 2021

Published: 30 March 2022

NOMENCLATURAL NOTE

http://dx.doi.org/10.38201/btha.abc.v52.i1.7

A new name for the illegitimate later homonym Leonotis capensis (Benth.) J.C. Manning & Goldblatt (Lamiaceae: Lamioideae)

John C. ManningI, II

ICompton Herbarium, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Private Bag X7, Claremont 7735, South Africa

IIResearch Centre for Plant Growth and Development, School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, Private Bag X01, Scottsville 3209, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The new combination Leonotis quinquedentata J.C.Manning & Goldblatt is provided as a replacement for the illegitimate later homonym L. capensis (Benth.) J.C.Manning & Goldblatt (2010), non L. capensis Raf. (1837).

Keywords: Africa; Leonotis (Pers.) R.Br.; Leucas R.Br.; nomenclature; taxonomy.

Introduction

Morphological and molecular studies in Leucas R.Br. and allied genera in the Lamiaceae (Ryding 1998; Scheen & Albert 2009) have confirmed earlier suggestions by Singh (2001) that the Asian and Arabian-African taxa comprise two distinct phylogenetic lineages. From these studies, the African species of Leucas are now understood to be more closely allied to the other African members of the group in the genera Acrotome Benth. ex Endl., Isoleucas O.Schwartz, Leonotis (Pers.) R.Br. and Otostegia Benth., and Leucas has consequently been more narrowly circumscribed to include only Asian taxa (Scheen & Albert 2007).

As part of circumscribing monophyletic genera among the African taxa, Scheen & Albert (2007) transferred a species of Otostegia to each of the two genera Isoleucas and Moluccella L., and segregated a further four species in the new genus Rydingia Sheen & V.A.Albert. They further recommended that the remaining African species in the group be treated as part of an enlarged Leonotis. This recommendation was partially implemented by Manning and Goldblatt (2012) in their transfer of the southern African species of Leucas to Leonotis. The traditional separation of Leonotis from Leucas was based on the size of the flowers and on the colour and proportions of the corolla, and these differences are now understood to reflect differences in pollination systems: the larger, orange flowers with reduced lower lip of Leonotis s.str. are consistent with bird pollination and the smaller, white, more equally bilabiate flowers of Leucas s.lat. with insect pollination (Iwarsson & Harvey 2003). The small genus Acrotome (8 spp.) has been provisionally retained pending further resolution of relationships in the group.

In its current circumscription, Leonotis is a genus of up to 60 or 70 species of annual or perennial herbs or subshrubs recognised by their strongly verticillate inflorescences with leaf-like bracts, and flowers with a 5- to 10-toothed calyx that is glabrous within, and a white or orange corolla with a bearded upper lip. Acrotome is morphologically distinctive in its beardless upper lip and included stamens held together by intermingling hairs (Codd 1985).

Unfortunately, one of the combinations in Leonotis published by Manning and Goldblatt (2012), L. capensis (Benth.) J.C.Manning & Goldblatt, is an illegitimate later homonym for L. capensis Raf. (1837). The latter name was proposed by Rafinesque (1837) as a replacement name for Phlomis leonitis L. when he transferred that species to the genus Leonotis to avoid a possible tautonym (Turland et al. 2018: ICN Art. 23.4). The combination L. leonitis does not, however, exactly repeat the generic name' (Art 23.4) and is therefore not a tautonym. It is, therefore, an illegitimate superfluous name for P. leonitis (Turland et al. 2018: ICN Art. 52.1), which epithet should have been used. No additional names are available for this taxon and the new name L. quinquedentata is provided here. The epithet refers to the five-lobed calyx that is distinctive for the species.

Leonotis quinquedentata J.C.Manning & Goldblatt, nom. nov. pro Lasiocorys capensis Benth., Labiata-rum genera et species 6: 600 (1848). Leucas capensis (Benth.) Engl.: 268 (1888). Leonotis capensis (Benth.) J.C.Manning & Goldblatt: 809 (2012), nom. illeg., non L. capensis Raf.: 88 (1837), nom. illeg. superfl. pro Phlomis leonitis L.: 398 (1767) [ = Leonotis ocymifolia (Burm.f.) Iwarsson].

References

Bentham, G., 1848, Labiatarum genera et species, Treuttel & Würtz, Paris. [ Links ]

Codd, L.E., 1985, 'Lamiaceae', in O.A. Leistner (ed.), Flora of southern Africa, 28(4), 19-23, Botanical Research Institute, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Engler, A., 1888 ['1889'], Plantae Marlothianae. Botanische Jahrbücher für Systematik, Pflanzengeschichte und Pflanzengeographie, 10, 242-285. [ Links ]

Iwarsson, M. & Harvey, Y., 2003, 'Monograph of the genus Leonotis (Pers.) R.Br. (Lamiaceae)', Kew Bulletin, 58, 597-645. [ Links ]

Linnaeus, C., 1767, Systema Naturae, 12th edn., Salvius, Stockholm. [ Links ]

Manning, J.C. & Goldblatt, P, 2012, Plants of the Greater Cape Floristic Region, Vol. 1: the Core Cape flora. Strelitzia 29, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. http://opus.sanbi.org/bitstream/20.500.12143/5609/1/Manning_et_al_2012_Strelitzia_29.pdf [ Links ]

Rafinesque, C.S., 1837, Flora Telluriana, vol. 3. Probasco. [ Links ]

Ryding, O., 1998, 'Phylogeny of the Leucas group (Lamiaceae)', Systematic Botany, 23, 235-247. https://doi.org/10.2307/2419591. [ Links ]

Scheen, A.-C. & Albert, V.A., 2007, 'Nomenclatural and taxonomic changes within the Leucas clade (Lamioideae; Lamiaceae)', Systematics and Geography of Plants, 77, 229-238. [ Links ]

Scheen, A.-C. & Albert, V.A., 2009, 'Molecular phylogenetics of the Leucas group (Lamioideae; Lamiaceae)', Systematic Botany, 34(1), 173-181. https://doi.org/10.1600/036364409787602366. [ Links ]

Singh, V., 2001, Monograph of Indian Leucas R.Br. (Drona-pushpi) Lamiaceae. Scientific Publishers, Jodphur. [ Links ]

Turland, N.J., Wiersma, J.H., Barrie, F.R., Greuter, W., Hawk-sworth, D.L., Herendeen, PS., Knapp, S., Kusber, W.-H., Li, D.-Z., Marhold, K., May, T.W., Mcneill, J., Monro, A. M., Prado, J., Prica, M.J. & Smith, G.F. (eds.), 2018, International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China, July 2017, Regnum Vegetabile 159, Koeltz Botanical Books, Glashütten. https://www.iapt-taxon.org/nomen/main.php. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

John C. Manning

e-mail: J.Manning@sanbi.org.za

Submitted: 7 January 2022

Accepted: 20 April 2022

Published: 19 May 2022

ORIGINAL RESEARCH, REVIEWS, STRATEGIES AND CASE STUDIES

To be or not to be a protected area: a perverse political threat

Andrew Blackmore

Manager: Conservation Planning, Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife; Research Fellow, School of Law University of KwaZulu-Natal

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: On 15 January 2021, a South African Member of the Executive Committee (MEC) for the Environment amended the Mabola Protected Environment's (MPE) boundaries to remove legal impediments preventing coal mining in this protected area. This decision came in the wake of the MPE being declared a protected area and a series of court cases ending at the Constitutional Court.

OBJECTIVE: The objectives of this paper were: (1) evaluate the potential consequences of the MEC's decision for South African protected areas; (2) speculate on the possible impact on South Africa's reputation in terms of its commitment to safeguarding its protected areas; (3) identify possible weaknesses in the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act 57 of 2003 (NEMPAA); and (4) make recommendations to strengthen this Act so that it can reduce the vulnerability of protected areas to arbitrary and prejudicial decision-making

METHODS: This study involved an evaluation of NEMPAA and the notice in the Provincial Gazette declaring and giving effect to the MEC's decision, and of the various High Court judgments leading up to and following the publication of this notice.

CONCLUSION: The decision by the MEC highlights the vulnerability of protected areas and the importance of the conservation of biodiversity, particularly in a context of parochial or partisan objectives and profit-vested interests that are of a limited (at least in the medium- to long-term) public benefit. It is concluded that the discretionary clauses in NEMPAA may need to be amended to limit or refine the discretion politicians may apply.

Introduction

Protected areas are deemed to be the bastions of biodiversity conservation and the core of the natural environment held in trust for the benefit and enjoyment of current and future generations (Blackmore 2020; Lubbe 2019; Radeloff et al. 2010). It is therefore not unreasonable to assume - at least from a principle perspective - that protected areas, once established, would persist ad infinitum and that their biodiversity would be protected from at least human-induced harm (Hoffmann & Beierkuhnlein 2020; Qin et al. 2019). The corollary is that each generation would, in turn, inherit a network of protected areas that contains viable components of the country's biodiversity (Mogale & Odeku 2018; Zurba et al. 2020). Thus, in addition to being a custodian or trustee, there is an expectation that each generation would increase the number and size of the existing protected areas to a point where, as a minimum, the network of protected areas contains a viable representation of the country's biodiversity. Thus, the decisions taken in one generation have a direct consequence not only for that generation, but also for future generations (Lubbe 2019). The longevity of a protected area is, therefore, founded on the trustee's ability to safeguard (protect) the area.

While the meaning of a protected area has been defined in many texts, the concept of being protected is rarely, if at all, defined. Consequently, the common interpretation of the term is used. Collins online dictionary defines protected as 'forbidden by law to be harmed', while the Merriam-Webster online dictionary defines the term as 'to cover or shield from exposure, injury, damage, or destruction, or to maintain the status or integrity of especially through financial or legal guarantees'. It is reasonable, therefore, to assume that in the context of this paper, 'protected' means that the protected area must be safeguarded from being damaged, diminished, attacked, stolen, injured, lost, and the like. Furthermore, strict application of this interpretation would, in principle, result in the protected area persisting and fulfilling the purpose for which it was established over time.

Despite this understanding, regulatory bodies have not embraced the need of a protected body to persist ad infinitum. For instance, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines a protected area as 'a clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values' (author's emphasis).

The inclusion of the term '[in] the long-term' suggests that the IUCN envisioned that the life of a protected area, although unknown, is finite but persists beyond the foreseeable future (or beyond the short to medium term) (Blackmore 2020). It is, therefore, conceivable that the IUCN conceptualised, for whatever reason, that a protected area may be established for an extended period, during which time the integrity of the biodiversity (and other values therein) is shielded from, at least, anthropogenic harm and with a future possibility of it being discontinued. The corollary is that while the protected area is in existence, it is maintained and protected in a fit state - i.e., it fulfils the purpose for which it was set aside as a protected area by its trustee or trustees. Here the trustee would comprise the state and, if different, the management authority.

The trustee role of the state would be to provide the necessary governance instruments (legal and policy framework) for the establishment and management of the protected area. In contrast, the trustee role of the management authority would be to give effect to day-to-day management of the protected area in accordance with, at least, these governing instruments (Goosen & Blackmore 2019). Thus, on establishing a protected area and following the assignment of a management authority, the state assumes an oversight role to ensure that the integrity of the protected area is reasonably safeguarded in the public interest by the management authority (Atmis 2018). In a South African context, the oversight role would be primarily exercised in accordance with the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act 57 of 2003 (NEMPAA).

NEMPAA provides for several of kinds of protected areas that may be established in South Africa. This array extends from giving protection to one or more natural or cultural features (e.g., a protected environment) to prohibited access by people save for that required under exceptional and necessary circumstances (e.g., a special nature reserve). A summary of the kinds of protected areas in South African law is provided in Fuggle and Rabie (Strydom & King 2009). The origin of a 'protected environment' is rooted in the Protected Natural Environment (PNE) in the Environment Conservation Act 73 of 1989 (ECA)(RSA, 1989). This component of the Act was repealed by the NEMPAA, which redefined the 'Protected Natural Environment' to 'Protected Environment'(PE) to cater for cultural attributes needing protection. Nonetheless the erstwhile PNE and current PE purpose remained unchanged. This being to 'enable private landowners to take collective action to protect one or more attributes of their properties' (Blackmore 2022).

Discussion

The plight of protected areas

Despite the legislative instruments, protected areas and the biodiversity therein suffer from many threats that extend from unsustainable use of natural resources to mismanagement or improper conservation management, to encroachment by incompatible land-use change and development, and to climate change (Cop-pa et al. 2021; Hoffmann & Beierkuhnlein 2020; Mascia & Pailler, 2011; Prato & Fagre 2020). These threats, either individually or cumulatively, may lead to the loss of a protected area function (viz. a paper park) or the loss of part or all of the protected area through deregis-tration or degazettement (De Vos et al. 2019; Mascia & Pailler 2011; Qin et al. 2019).

The need for a protected area to at least be downsized or degazetted in recent protected area jurisprudence and statute law, has twinned the need for the establishment of new protected areas and the expansion of existing ones. Such provisions provide the relevant state authority - particularly the political head - with the powers to act and make decisions in the State's and therein the public's (current and future generations) best interests. The establishment and formalising of a protected area in law are generally conditional: the parcel of land needs to meet particular biodiversity or ecosystem standards or requirements. In contrast, the withdrawal of a parcel of land from the protected area estate invariably occurs without any significant limitation or challenging legal restriction (see, for instance, Mascia & Pailler 2011).

Protected area downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement (PADDD)

In South Africa, the withdrawal of a protected environment, special nature reserve, national park or nature reserve belonging to the state requires the oversight and a resolution of the relevant national or provincial legislature. In contrast, a boundary of a marine protected area may be amended, or the declaration may be withdrawn at the sole discretion of the (national) Minister responsible for the environment. A similar circumstance applies to private nature reserves or where private land has been incorporated into a national park. In this instance, the relevant political head (the national Minister - the Minister; or the Member of the Executive Committee, also commonly referred to as the 'provincial minister' - the MEC) for the environment must, without consideration, degazette the private land on receipt of a notice from the landowner requesting this (See Chapter 5 - RSA 2004). Thus, the long-term security of these protected areas must be questioned in that the persistence of the protected area is vulnerable to the discretion of a political head or landowner.

While the politicians involved in the degazetting of a parcel of land or sea are obligated to act as a trustee of South Africa's protected areas (see Section 3 - RSA 2004), the NEMPAA is silent on the consequences should this obligation be disregarded. Furthermore, while the Act is explicit on the circumstances and criteria that need to be met for either a terrestrial or marine protected area to be declared, it is silent on the circumstances under which degazetting may occur. Thus, other than the obligation to act as a trustee of protected areas - a provision of NEMPAA that is possibly the least understood (Blackmore 2018; Van der Schyff 2010) - there is no explicit provision in NEMPAA that binds the political head and the relevant legislature to ensure that the downsizing or degazetting of a protected area does not compromise the objective and intent of this Act. Nonetheless, the fulfilment of the trustee obligations with respect to downsizing or degazetting of a protected area and maintaining the integrity of the public trust entity (the network of protected areas in South Africa) has taken place in in this country's recent conservation history. For example, the Vaalbos National Park was degazetted to grant successful land claimants' beneficial occupation of the properties that comprised that protected area. To compensate for or offset this loss to the public trust entity, the Minister gazetted the establishment of the Mokala National Park (SANParks 2021).

As with the marine protected areas and private nature reserves, the amendment of the boundaries or withdrawal of a protected environment is not overseen by the national or provincial legislature. The political head for the environment may, therefore, notwithstanding the public trust obligation:

a. 'withdraw the declaration [...] of an area as a protected environment or as part of an existing protected environment; or

b. exclude any part of a protected environment from the area' (Section 29 of NEMPAA).