Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Bothalia - African Biodiversity & Conservation

On-line version ISSN 2311-9284

Print version ISSN 0006-8241

Bothalia (Online) vol.51 n.2 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.38201/btha.abc.v51.i2.13

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

MISCELLANEOUS NOTES

Mushroom art in South Africa and Zimbabwe - Emil Holub: 1847-1902

Cathy Sharp; Rob S. Burrett

Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe, Bulawayo. P.O. Box 9327, Hillside, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

ABSTRACT

Emil Holub was a nineteenth century, Austro-Hungarian Czech, medical doctor with wide-ranging interests in ethnography and the natural sciences. During visits to southern Africa in the 1870s, he meticulously recorded everything that he encountered. Amongst his vast collection of artifacts, natural history specimens and notes were several sketches of fungi. These illustrations are reproduced here to document this valuable historical knowledge, tentatively identifying them in the context of the habitats through which Holub travelled.

Key words: southern African history; macro-fungi; South Africa; Zimbabwe; natural history; artistic records.

Introduction

The late 19th century era saw many adventurers visiting Africa in search of ethnological or natural history curiosities. Emil Holub was one. He was born on 7 October 1847 in Holice (Holitz), eastern Bohemia, in what is now the Czech Republic. As a youngster he exhibited a remarkable passion for natural history, geography and archaeology, and was an avid reader of many of the leading travelogues of that period. As a result of the writings of David Livingstone, Holub became obsessed with the African continent, and it was his avowed ambition to follow in Livingstone's footsteps. To this end, he explored southern Africa twice: most extensively in 1872-1879 and again from 1883 to 1887 (Burrett & Olsa jr 2006; Burrett 2006).

Holub studied medicine at Charles University, Prague, and left for South Africa in May 1872. Arriving at Cape Town on 1 July, he spent a short time in Port Elizabeth (Gqeberha) before making his way to the Diamond Fields where he set himself up at Dutoitspan. Holub worked hard and lived frugally, saving his money to fund his proposed travels into the interior. These journeys are well documented, and it is the English translations of his books that are referred to in this paper (Holub 1881; Holy 1975).

In early February 1873, Holub undertook his first excursion into the west of the old Transvaal Republic. This lasted two months, during which he collected about 1 500 dried plants and an enormous quantity of other natural history specimens, including over 3 000 insects. A short while later, November 1873 to April 1874, Holub was again on the move, this time travelling to Shoshong in what is today Botswana (Kandert 1998). Holub's third expedition began on 2 March 1875. This time he set out for the Zambezi River by way of the 'Salt Pan Road'. During this 21-month long journey, Holub passed through the arid wilderness between Botswana's Makgadikgadi Salt Pans and the Zambezi River. At the end of July 1875, he reached Pandamatenga, a key pre-colonial trading centre. With the support of trader George Westbeech, Holub received permission to cross the Zambezi to spend time in the Lozi (Barotse) Kingdom of Western Zambia. In December 1875, Holub had a disastrous mishap when his canoe overturned in the Zambezi, losing provisions, medicines and many of his notes and specimens (Hol-ub 1881 - Vol.2; Burrett 2006). This forced him to turn back, and he finally returned to Kimberly in November 1876.

On 5 August 1879, Holub left Cape Town and returned to Prague via London, spending the next four years writing up his travels, giving lectures and presenting displays of his collections in many European cities. In 1883 he returned to Africa accompanied by his wife Rosa, and in June 1884 they embarked on an ambitious attempt to travel far beyond the Zambezi River. This journey, funded by the Austro-Hungarian State, was a disaster, and by April 1886 the expedition was aborted after the death of several of his companions and the loss of all his equipment and accumulated field-notes. Holub finally returned to Europe in 1887 and died in February 1902 as a result of the accumulated long-term effects of malaria. Today Emil Holub is considered one of the national folk-heroes of the Czech Republic and one of the greatest scientific travellers of the 19th century.

Clearly Holub had an uncommon passion for natural history as well as an eye for detail, and his fascinating mushroom drawings are uncommon since fungi were rarely noticed by most likeminded travellers. We hope that this publication, a historical review of these early southern African fungi sketches, will give recognition to the valuable pioneer contribution of Emil Holub to my-cological knowledge in southern Africa and encourage further research.

Materials & Methods

Most of Holub's observations have remained unpublished, so it was a privilege for one of us in 2007 to be granted permission to see Holub's drawings in the Náprstek Museum in Prague, as part of a general heritage project funded by the Czech Embassy, Harare. This was facilitated by the then Czech Ambassador to Zimbabwe, Jaroslav Olsa Jnr. Subsequently, Bohumil Hamrsmid of the Czech Embassy in Lusaka, Zambia, was approached for assistance with translation of the annotations alongside the sketches. Contrary to our expectations, he found that most of the text was not written in Czech, but in archaic German, with only a smattering of Czech here and there. Hamrsmid found the German very difficult to read, let alone translate and we approached Helga Landsmann who is familiar with the old Sütterlin script and old style of handwriting. On many pages there are several styles of writing and pen quality/size. We believe that additions were made later by the curatorial staff in the Museum, but they add little to the nature of the illustrations and original annotations and are therefore not discussed further.

Holub's two 1881 volumes were read to provide some insight into the background of the various mushroom sketches, so enabling us to understand general habitat and timing of the journey when these fruiting bodies were illustrated. Unfortunately, it was not always possible to match the sketches with the published texts, and the exact localities of the illustrations are often obscure, using old geographical names no longer in use, or they are a distorted version of what he thought was said in Cape Dutch or various African languages. In addition, we have found that the official English translation, done by Ellen E. Frewer, has many variations to the original text. A fair amount of the natural history detail was dropped as Frewer believed that they would have little appeal to the general English reader. This has made it difficult to correlate the published text with some of the annotations in Holub's original field-notes. Nonetheless it appears that the mushroom drawings come from three general areas, and it is on this basis that we discuss his sketches (Figure 1).

The original sketches, scanned by the staff of the Náprstek Museum in Prague, are in sepia, but they are reproduced here in black-and-white to enhance their finer details. The drawings were done on whatever paper Holub had on hand as paper was a rare commodity at that time. His original numbering is retained. Measurements of size on the sketches were given in the old imperial style and Holub, in his characteristically precise manner, used the 'triple primes', i.e., three apostrophe signs (''') to denote a twelfth of an inch.

It is appreciated that the exact determination of a species cannot always be achieved by illustration alone. It is not known whether Holub's fungi collections survived the journeys, and it would be interesting to confirm the tentative identifications below with relevant voucher specimens in the Náprstek Museum. Nonetheless, Holub's attention to detail is such that the genus, and sometimes a species name, can be allocated to his sketches. Obviously, some of our interpretations may be open to dispute, because by its very personal nature, any work of art is very individualistic and influenced by the knowledge and experience of the artist. Equally, interpretation is influenced by the knowledge and experience of the reviewing eye. The nomenclature used in this paper is according to Index Fungorum (2020).

In late December 2018, a field trip was undertaken by the first author and Judy Ross to explore the sites along the Pandamatenga-Leshumo Valley trail as described by Holub in his publications. Our intention was to verify the vegetation present, which would assist in naming the illustrated fungi. Unfortunately, the rains were very late that season, and no mushrooms were seen during our week-long excursion.

At the end of this paper, we include two written records of fungal collections from southern Africa attributed to Holub that have come to light in more recent literature. These may be only part of his forgotten legacy. It is possible that there are additional mushroom illustrations archived in the Náprstek Museum.

Results and Discussion

Holub's first published mention of 'funguses' is on 26 July 1875 in Volume 2 of his travelogues (Holub 1881), together with a note about explosive seed pods. This latter phenomenon applies to Brachystegia, Julbernar-dia and Baikiaea trees, which Holub encountered at that time of year while travelling north 'through very monotonous sandy forest' towards the settlement of Pandamatenga. These trees are in the Caesalpinioideae sub-family of legumes, and the first two genera are dominant in miombo woodland and have ectomycorrhizal associations with many fungi. They often co-exist with Baikiaea plurijuga Harms, the Zambezi teak tree, which is dominant in many of the Kalahari Sand areas. It is unlikely that there were fungi fruiting at that time of year, except for bracket fungi, which Holub apparently did not illustrate, but he collected 'a good many plants, and some varieties of seeds, fruits and funguses'.

The next mention of fungi is made during Holub's stay in the Upper Leshumo Valley where he was recovering from a particularly bad bout of 'fever'. On 19 January 1876 he was well enough to take a short walk and botanised in the immediate vicinity of the wagons - 'Of such funguses as I could neither press nor dry, I took sketches...'.

The annotations to his sketches, unlike the published text, mentions 'mushroom' using the old German term 'Schwamme' ('sponge mushrooms'), a name with which he would have been familiar back home, although in using this word he meant more than 'bolete' fungi to which this common name is now applied in Zimbabwe. It is interesting that he also mentions lichens in his books, for example in rocky areas north of Moshaneng. This suggests that he knew that they, and probably also fungi, were separate from plants. Unfortunately, his descriptions of the lichens are not detailed enough to identify those he encountered.

The drawings and translations of the annotations to Holub's field sketches are documented and our identifications follow below. These are summarised in Table 1.

1. The Gariep (Vaal)-Harts River Region, South Africa, 1873.

Holub collected various natural history specimens in the western and central areas of the former Transvaal, including the modern provinces of Gauteng, Limpopo and North West as well as in the immediate vicinity of Kimberly. These collections date to 1873 and January 1874. The general habitat of these river valleys where he did considerable work is described as 'desert scrub' (Pole-Evans 1936) or part of the savanna biome in the Eastern Kalahari Bushveld Bioregion (Mucina & Rutherford 2011).

In March 1873 Holub found Phellorinia herculeana (Pers.) Kreisel 1961 (syn. Phelloriniastrobilina, Phellorinia inquinans), (Figure 2, Holub No.4), 'along the way in the grass between Driefontein and .... (near Platberg)'. The unknown name in the annotation cannot be deciphered despite reference to his map. There follows a description of colour of the specimen which could be any one of the following - whitish, yellowish or brownish. The writing is unclear, hindering translation. Unfortunately, little else of the text can be read. The sizes recorded by Holub fit the species well and he has captured the exact character of this fungus. There are several records of this species in South Africa, two of which were recorded in Fauresmith and one along the Vaal River (Doidge 1950), which would seem to fit the location where Holub encountered it. There are three records from Zimbabwe in the private collection of Cathy Sharp, all found in heavy, alluvial soil along major rivers (collections CS699 and CS1069 and ZSES17). There is a chance that this sketch (and the Zimbabwean collections) may be Dictyocephalos attenuatus (Peck) Long & Plunkett 1940, a species very similar to P herculeana both macro- and microscopically (Dios et al. 2002) and previously collected in Hwange, Zimbabwe (Doidge 1950).

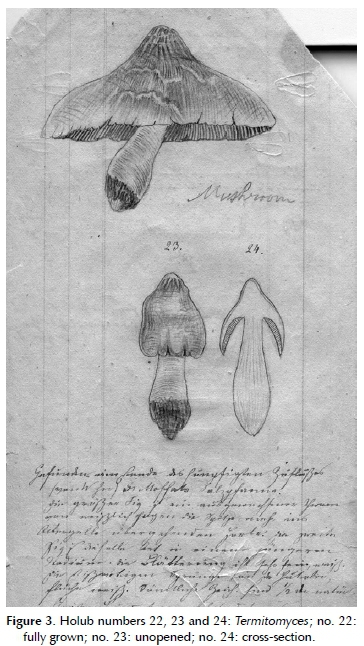

Figure 3 (Holub numbers 22, 23, 24), shows a characteristic termite fungus, Termitomyces. The details of the rough cap surface suggest that this is possibly Termitomyces sagittiformis (Kalchbr. & Cooke) D.A.Reid 1975 (Van der Westhuizen & Eicker 1994), although Termitomyces umkowaan (Cooke & Massee) D.A.Reid 1975 may also develop a cracked cap with age. Both species have a swollen base to the stipe before narrowing into a black pseudorrhiza as shown in Holub's illustration. A more precise identification to species is therefore not possible. The location of this specimen is given as 'Found in the sand of the swampy tributary... [west...] Dr Moffat's salt pans'. These pans are marked on Holub's map, west of the Harts River near Mamusa. 'The biggest figure is a fully grown sponge, the white of the mushroom blending into yellowish.the gills are white.grows with termite mounds.' Unfortunately, the rest of the annotation is indecipherable.

2. The Mahikeng (previously Mafeking) area, South Africa, 1875.

In North West Province, South Africa, Mahikeng is close to South Africa's northwestern border with Botswana. Its habitat is open veld comprised of short mixed grass with low scrub along the banks of the Molapo River (Pole-Evans 1936). Mucina and Rutherford (2011) classified the area as being on the edge of Savanna and Grassland biomes.

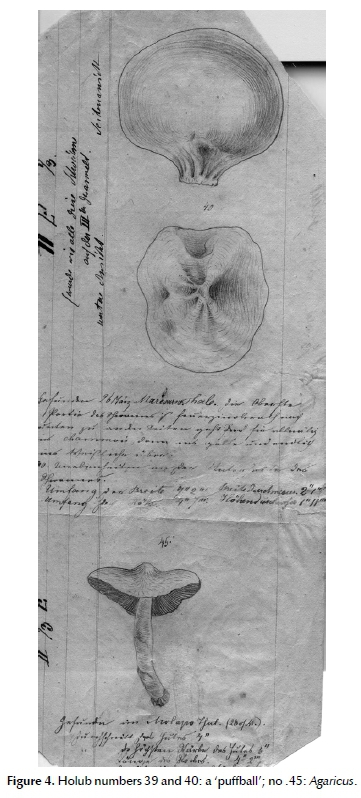

The illustration in Figure 4 (Holub numbers 39 and 40), is possibly one of the 'puffballs', perhaps a Calvatia with the typically crimped folds underneath. This group of fungi were formerly in their own family called Lyco-perdaceae but are now in Agaricaceae. Holub shows the 'side-view' (no. 39) and 'under-view' (no. 40). 'As all sponge mushroom...on the third...Found on 26th of March....' If the translation is correct, it is not clear which measurements Holub took of the fruiting bodies: 'circumference of the width 7'' 2''' cross-section of width 2'' 1''' circumference of the height 4'' 7''' diameter 1'' 11'''.'

The Agaricus (Figure 4: Holub no. 45) was 'found in Molapo Valley on 28th October.' The Molapo River forms the southern border of Botswana. The mushroom noted by Holub measured as follows: 'cross-section of the closed cap is 4'', cross-section of the open cap is 6'', cross-section height of the cap is 4'' 2''' circumference of cap is 11'''. It is not clear whether there is more to the last measurement as the page is damaged. Of interest is the date when this mushroom was found and illustrated. October is usually very hot and dry, and one would not expect fruiting at this time, although thunderstorms do occur, and temporary moisture and humidity may well encourage growth of these mushrooms.

Figure 5 shows another Agaricus. Holub no. 44 has a rather obscure caption written in a different language, possibly Czech or Slovak - 'page 25 in diary.' We assume that this refers to one of Holub's personal diaries, which we have not seen. The half-fraction shown alongside appears to refer to this same specimen, suggesting that it is a very large species.

Illustration no. 46 looks to be Coprinus comatus (O.F.Müll.) Pers. 1797. It is shown as a third of life-size and was 'found in the Molapo Valley.' However, there are some species of Agaricus that look like this in the young stage, and it may represent the same fungus in the adjacent illustrations. However, because Holub allocated a different number to this drawing, we assume it to be a different mushroom.

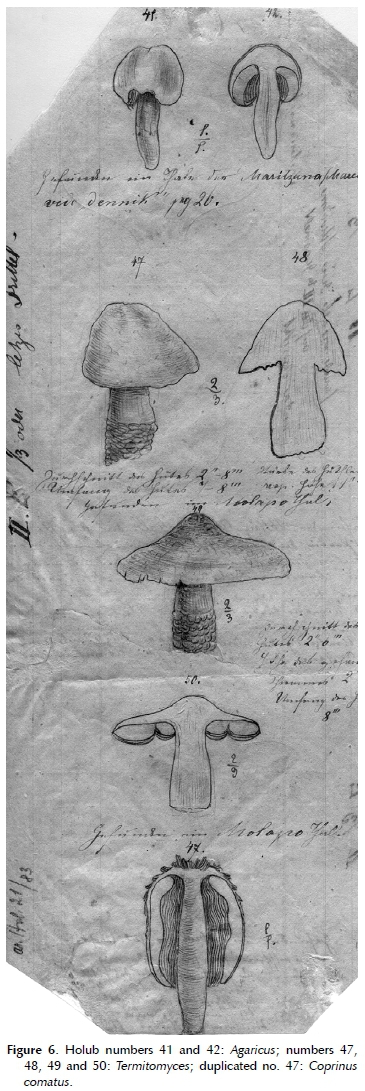

In Figure 6, Holub numbers 41 and 42 look like young Agaricus fruiting bodies. They are annotated 'Found in the valley of Maritzana/ .... [Marikana?]', 'from diary page 26.' It is not certain what the 'fraction' represents, but it possibly means life-size. The next four pictures (numbers 47, 48, 49 and 50), show another Termitomyces, possibly Termitomyces schimperi (Pat.) R.Heim 1942, judging from the details of the stipe and its general robust habit. The first two are labelled 'Cross-section of cap 2'' 8''', circumference of cap 7'' 8"'...1" 6'''. Found in the Molapo Valley.' The note between pictures 49 and 50 reads 'Cross-section of cap 2'' 6'''. Height of the found mushroom 2"...Circumference of the cap...8"' found in the Molapo Valley.' Unfortunately, the right-hand side of the scanned image is missing.

The picture at the bottom of Figure 6 has a duplicated 'no. 47' and looks like a cross-section of the C. coma-tus, which appeared in Figure 5. There are no notes pertaining to this sketch, but the annotation on the left-hand side may be a brief cross-reference to Holub's notes e.g., 'Hol. 21/83.' Perhaps it alludes to a page in his diary or a collection item no. 21. Similar annotations are to be found on many of Holub's sketches.

Figure 7 (Holub no. 52) shows the meticulous detail of what we believe to be the non-mycorrhizal Amanita pleropus (Kalchbr. & MacOwan) D.A.Reid. It is labelled 'found in the Molapo Valley. Circumference of the cap 16'' 6'''. Cross-section through the cap 5'' 2'''. Length of the '...rundes' 6'' 4''' ". The last sentence cannot be deciphered, but the size of the feature (6''') may refer either to the ring on the stipe or to the basal structure. The latter is very interesting and must have been remarkable enough for Holub to make a point of illustrating it. First impression suggests a small volva or volval remains typical of an Amanita, but mycelia tufts may also be present at the base of Macrolepiota species (pers. observation Cathy Sharp), a feature not often noticed unless the substrate litter is carefully brushed off.

3. Pandamatenga, Zimbabwe, 1875-1876.

The historical site of Pandamatenga occupied the crest of a low hill overlooking riverine vegetation and open grassland at the headwaters of the Matetsi River, a tributary of the Zambezi (G. Macdonald pers. comm.). The vegetation further north along the trail is predominantly Kalahari sand teak woodland with scattered Brachy-stegia boehmii Taub. and Julbernardia globiflora (Benth.) Troupin. It is in this woodland that ectomycorrhizal fungi were encountered by Holub and some of his drawings depict these genera (Figures 8 & 9). Additional patches of mopane (Colophospermum mopane (Benth.) J.Léonard) grow on black clay and cut across the sand in an east-west direction, often forming pans and vlei areas, which are water-logged in the rainy season.

Figures 8, 9 and 10 illustrate some of the fungi that Holub encountered in the 'Leshomo' Valley, north of Pandamatenga. The Upper Leshumo Valley is stony and dominated by Combretum vegetation and te upper reaches of the Leshumo River are flanked by teak woodland on sand, with some Brachystegia species and J. globiflora. This area is within easy walking distance of where Holub would have been camped away from the tsetse fly during January and February of 1876, and the ectomycorrhizal mushrooms that he sketched would have been fruiting at that time.

Dropping into the valley northwards, the current habitat is Vachellia tortilis (Forssk.) Galasso & Banfi woodland growing on grey alluvial soil, although remnants of huge Faidherbia albida (Delile) A.Chev., seen in 2018, suggest that these trees may have been more prevalent in Hol-ub's time. Towards the confluence of the Leshumo and Zambezi rivers the vegetation opens out into clumps of Boscia spp. and regenerating Vachellia and Senegalia species. These low-lying plains became impassable during the rains and were in a belt that had tsetse fly, hence Holub and the traders and missionaries who came this way were forced to leave their wagons up-country in the Upper Leshumo Valley.

The following is Holub's description of the Leshumo Valley: "...slightly hilly, only several hundred metres wide, covered with high grass and park-like woods and is bordered on both sides by high laterite ridges. At the end of Valley a spur of the left laterite ridge stretches towards the right one. This heavily wooded spur was supposed to be the remaining tsetse area whereas flat part covered with grass, bush and shrubs was supposed to be free of tsetse from spurs to Chobe and Zambezi rivers.. '

Figure 8 is labelled: 'Sponge mushrooms of the upper Leshoma Valley and its immediate surroundings.' It shows a range of five species. Number 433 is Parasola plicatilis (Curtis) Redhead, Vilgalys & Hopple 2001, which is commonly found on old dung or well-rotted wood. Number 434 looks like an ectomycorrhizal Russula or it could be a Clitocybe with its slightly twisted stipe. Numbers 435 and 436 are two stages of development of Leucoagaricus, possibly Leucoagaricus melea-gris (Gray) Singer 1949, (syn. Leucocoprinus meleagris). The drawing shows a particular attachment to an unknown substrate, but in real life they are usually found on dead wood. Number 437 is a Lentinus/Panus, possibly Panus neostrigosus Drechsler-Santos & Wartchow 2012 (syn. Lentinus strigosus), which is very common and has a characteristically short stipe. Number 438 could be Laccaria, another ectomycorrhizal species, but this is usually associated with Eucalyptus trees, none of which would likely have been in that area in Holub's time. More recently there have been a few collections that might be indigenous species, but this genus has been little-studied in Africa.

Figure 9 shows six different species of 'Sponge mushrooms of the Leshoma Valley.' Number 439 looks like the ectomycorrhizal Cantharellus miomboensis Buyck & V.Hofst. 2012 with a roughly textured stipe. The mushroom depicted as no. 440 is possibly another Laccaria in mid-stage of growth. As Holub linked numbers 440 and 445 with curled brackets and 'a'-'b', these may be the same mushroom at different stages. This genus is known to be very variable in Europe (A. Verbeken, pers. comm.) but there is limited information on the indigenous species (Sharp, unpublished). On its own, no. 445 has similarities to Cantharellus platyphyllus Heinem. 1966 or Cantharellus splendens Buyck 1994 and to Lepista, so it is hard to ascertain the precise identity. Number 446 with its twisted stipe is likely to be Marasmius or Collybia. Number 447 is possibly an Entoloma or Marasmius, while no. 444 is an Agaricus.

Figure 10 shows another range of mushrooms from 'Leshoma Valley'. Agaricus trisulphuratus Berk. 1885 is clearly illustrated in three stages of growth, (Hol-ub numbers 458, 459 and 460). This striking orange species is found in open patches of bare, clay-enriched, damp ground. Number 461 may be a tiny species of Podoscypha, which is associated with sedges and fine grass species. It is often encountered in open, damp grassland or wetlands, and is common throughout Zimbabwe. However, it may be an Ascomycete (A. Verbek-en, pers. comm) or an Omphalina-like species, none of which have been fully studied in Africa. Number 462 is Leucoagaricus sp., which is common in open grass habitats. Number 466 could be any one of three genera: Pluteus, Entoloma or Mycena.

A summary of the species shown in Holub's drawings with their localities is shown in Table 2.

While visiting Victoria Falls (September 1875 or October 1885), Holub collected a rust-fungus on one of the Dracaena species (Dracaenaceae), growing along the Zambezi River, probably in the rain forest. Many years later this was identified and named by Ethel Doidge as a new species in the Pucciniaceae rust family, Uromyces holubii Doidge 1941 (Doidge 1941).

Some of Holub's fungi collections appear to have been sent to Germany, because discovered amongst them was a new species that was named Broomeia ellipso-spora Höhn. 1905 (von Höhnel 1905; Doidge 1950). It is unknown when or where Holub collected this particular specimen, but the species has since been found in both South Africa and Zimbabwe.

Conclusion

Emil Holub's mushroom drawings constitute a valuable collection of natural history records. They give us insight into the finer details of the ecosystems through which he passed in the nineteenth century. Unlike most travellers of that time, he was more than a hunter and trader, and brought with him a sound knowledge and genuine interest in a variety of natural and social sciences.

This paper exposes some of the fascinating fungi illustrations that can be found in Holub's hitherto unanalysed papers in Prague. Undoubtedly some of these illustrations are of his specimens that are possibly now housed in one of the many museums across Europe in which he deposited collections. With these illustrations alone we have a valuable contribution to science, but it would be ideal to link them with their voucher specimens.

This alerts us to the probable existence of many inadequately documented collections housed in herbaria and museums throughout the world that hold valuable information, which needs to be studied and published. Revealing these mushroom drawings done by Emil Holub in the 1870s, and exploring their content, is a start to bringing this information to light.

Acknowledgements

The Czech Embassy in Harare facilitated the visit of one of us to the Náprstek Museum in Prague during which time these sketches, amongst many other fascinating subjects, were identified. We must thank Ambassador Jaroslav Olsa, Jr for his interest in encouraging us to explore the forgotten legacy of Emil Holub. Helga Landsmann is thanked for the time-consuming translation of Holub's notes accompanying the mushroom drawings. Gordon Macdonald, Roger Parry and Armston Tembo kindly provided information about the Pandamatenga, Leshumo and Kazuma areas respectively. Judy Ross's assistance on the field trip in 2018 was invaluable. Martin Sanderson is thanked for his efforts in deciphering Holub's measurements. We are grateful for Annemieke Verbeken's assessment of the identity of the mushrooms. Wild Horizons staff, particularly Richard Nsinganu, are thanked for their interest and support during the 2018 field trip. We are grateful for comments and advice from anonymous reviewers.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

CS (Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe) was project leader for a series of articles on Mushroom Art in Zimbabwe, RSB (Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe) recognised the value of Holub's drawings and requested copies while on an independent visit to Prague.

References

Burrett, R.S., 2006, Dark deeds: some hunting memoirs of the nineteenth century Czech traveller, Emil Holub, Mambo Press, Gweru. [ Links ]

Burrett, R.S. & Olsa, J. Jr., 2006, 'Emil Holub and the Tati and Wukwe Ruins, 1876', Zimbabwean Prehistory 26, 2-12. [ Links ]

Dios, M.M., Moreno, G. & Altés, A., 2002, 'Dictyocephalos attenuatus (Agaricales, Phelloriniaceae) new record from Argentina', Mycotaxon 84, 265-270. [ Links ]

Doidge, E.M., 1941, 'South African rust fungi IV', Bothalia 4, 229-236, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v4i1.1721 [ Links ]

Doidge, E.M., 1950, Special edition on South African fungi and lichens to the end of 1945, Bothalia 5, 1-1094, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1898, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1867, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1868, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1869, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1899, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1870, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1900, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1871, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1872, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1873, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1874, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1875, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1876, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1877, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1878, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1879, https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v5i1.1880. [ Links ]

Holub, E., 1881, Seven years in South Africa: travels, researches and hunting adventures between the Diamond-Fields and the Zambesi, 1872-79, Volumes I and II, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London. (Reprinted 1975, Africana Book Society, Johannesburg). [ Links ]

Holy, L. (ed.), 1975, Emil Holub's travels north of the Zambezi, 1885-6, Manchester University Press, Manchester. Index Fungorum, 2020, http://www.indexfungorum.org/ [ Links ]

Kandert, J., 1998, The culture and society in South Africa of 1870s and 1880s - Views and considerations of Dr Emil Holub, Náprstek Museum, Prague. [ Links ]

Mucina, L. & Rutherford, M.C. (eds.), 2011, 'The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland', Strelitzia 19, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Pole-Evans, I.B., 1936, A vegetation map of South Africa, Memoirs of the Botanical Survey of South Africa, 15, 1-23. [ Links ]

Van der Westhuizen, G.C.A., & Eicker, A., 1994, Fieldguide: Mushrooms of southern Africa, Struik Publishers, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Von Höhnel, F.V., 1905, 'Mykologische Fragmente II-XV', Oesterreichische botanische Zeitschrift LV, 3, 99-100. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Cathy Sharp

Email: mycofreedom@gmail.com

Submitted: 27 November 2020

Accepted: 20 May 2021

Published: 18 October 2021