Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Bothalia - African Biodiversity & Conservation

On-line version ISSN 2311-9284

Print version ISSN 0006-8241

Bothalia (Online) vol.46 n.1 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/abc.v46i1.2039

STRATEGIES OR INNOVATIVE CASE STUDIES

Making the case for biodiversity in South Africa: Re-framing biodiversity communications

Kristal MazeI; Mandy BarnettI; Emily A. BottsII; Anthea StephensI; Mike FreedmanIII; Lars GuentherIV

ISouth African National Biodiversity Institute, South Africa

IIIndependent consultant, South Africa

IIIFreedthinkers, South Africa

IVCentre for Research on Evaluation, Science and Technology, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Biodiversity education and public awareness do not always contain the motivational messages that inspire action amongst decision-makers. Traditional messages from the biodiversity sector are often framed around threat, with a generally pessimistic tone. Aspects of social marketing can be used to support positive messaging that is more likely to inspire action amongst the target audience.

OBJECTIVES: The South African biodiversity sector embarked on a market research process to better understand the target audiences for its messages and develop a communications strategy that would reposition biodiversity as integral to the development trajectory of South Africa.

METHOD: The market research process combined stakeholder analysis, market research, engagement and facilitated dialogue. Eight concept messages were developed that framed biodiversity communications in different ways. These messages were tested with the target audience to assess which were most relevant in a developing-world context.

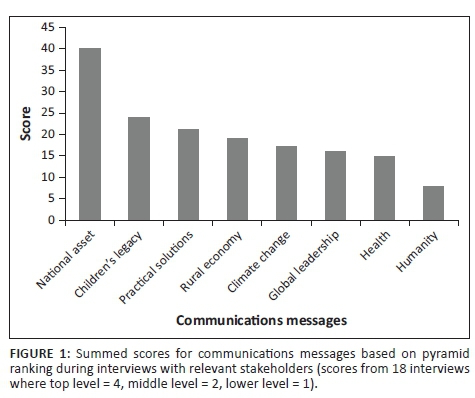

RESULTS: The communications message that received the highest ranking in the market research process was the concept of biodiversity as a 'national asset'. This frame places biodiversity as an equivalent national priority to other economic and social imperatives. Other messages that ranked highly were the emotional message of biodiversity as 'our children's legacy' and the action-based 'practical solutions'.

CONCLUSION: Based on the findings, a communications strategy known as 'Making the case for biodiversity' was developed that re-framed the economic, emotional and practical value propositions for biodiversity. The communications strategy has already resulted in greater political and economic attention towards biodiversity in South Africa.

Introduction

The very first of the Aichi Targets highlights the connection between biodiversity awareness and action: 'By 2020, at the latest, people are aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably' (CBD 2011). The increasing practice of formalised biodiversity communication, education and public awareness (CEPA) has resulted in a range of instructive materials on this topic (e.g. Hesselink et al. 2008). While CEPA provides a necessary foundation for improved biodiversity management and conservation, it often lacks the necessary motivation to inspire action amongst its audience (Schultz 2011).

An additional focus on targeted and appropriate communication is required to encourage positive action towards conserving biodiversity, particularly amongst policymakers. Communications theory characterises 'framing' as the way in which information is structured and organised into messages that can trigger unconscious associations. These affect how the information is understood and interpreted (Borah 2011; PIRC 2013; Wilhelm-Rechman & Cowling 2011). Framing theory involves both the content of a communications message (sociological framing) and the effects on receivers (psychological framing) (Borah 2011; Wilhelm-Rechman & Cowling 2011). There is often in biodiversity communications a mismatch in the framing of the sender and receiver, leading to ineffective communication and a perceived conflict between biodiversity messages and those of other sectors (Wilhelm-Rechman & Cowling 2011). More careful and conscious framing of messages can lead to better communication, which can be an important foundation towards stronger social marketing of biodiversity. Social marketing refers to the application of commercial marketing methods to influence positive behavioural change within society. Biodiversity conservation practitioners have begun to use aspects of social marketing to determine the most effective ways to inspire action amongst audiences (PIRC 2013; Veríssimo 2013). It is assumed that if biodiversity conservation professionals can learn to frame their messages in a way that will resonate with policymaker audiences, they are more likely to see increased understanding and uptake of their messaging.

Internationally, a consensus is emerging on how to frame biodiversity communication effectively. Futerra Sustainability Communications released their Branding Biodiversity report in 2010 (Futerra 2010), the findings of which were used as a basis for communications during the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)'s Biodiversity2010 campaign. Essentially, they found that, for a public audience, messages that invoked a love of nature were more effective than those emphasising the scale of loss of nature ('love not loss'). Monetary-based messages of 'need' were more important for policymaker audiences (Futerra 2010). For both the public and policymakers, communications messages were enhanced by a call to action (Futerra 2010). The Public Interest Research Centre (PIRC) in 2013 analysed the current frames used by environmental non-governmental organisations in the United Kingdom. This project likewise recommended avoiding messages of threat or loss and emphasising intrinsic values, such as enjoyment of nature (PIRC 2013). Research into framing of biodiversity communications has largely been focussed on developed European countries, with little information existing on whether these frames remain relevant in developing countries in other parts of the world.

In South Africa, as in other developing countries, there remains a perceived conflict between biodiversity conservation and economic development. South Africa's most serious social issues, and the highest priorities for government, include economic development, job creation, poverty alleviation and service delivery (DEA & SANBI 2011; Reyers et al. 2010). Despite progressive biodiversity legislation (such as the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (10 of 2004)) and strong biodiversity policies in South Africa, poor communication leads to a perceived lack of integration between biodiversity and development that undermines the biodiversity sector's work within the broader social context. For example, long-term biodiversity objectives such as protected area expansion, may appear to conflict with the short-term priorities of economic development and job creation (Kepe et al. 2004; King & Pervalo 2010; Snyman 2014). This conflict is further exacerbated by the fact that messaging from the biodiversity sector is often an unplanned collection of varied communications frames and differing terminology that does little to present a consistent and clear message. Consequently, many of the sector's messages do not elicit the intended responses from decision makers. Particularly when lobbying government for policy changes and funding, communication from the biodiversity sector is often dismissed in favour of more pressing messages from other sectors (DEA & SANBI 2011).

The South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), in collaboration with the national Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA), embarked on a process to improve the effectiveness of its communications to target stakeholders. This process combined market research, stakeholder analysis and engagement to understand how aspects of biodiversity conservation could be better communicated to decision makers.

The result of this process informed the 'Making the case for biodiversity' communications strategy, that describes how the biodiversity sector should reframe its communications to achieve the desired response (DEA & SANBI 2011). Experience such as this, generated within the conservation practice and policy arena, has seldom reached the academic literature (Veríssimo 2013). Indeed, there is little information in the formal literature that describes the methods, findings or uptake of communications campaigns, even those that have formed the growing global consensus on how biodiversity communications should be framed (e.g. Futerra 2010 or PIRC 2013). Therefore, the present paper serves to outline the methods taken in applying social marketing to biodiversity communications in South Africa, and to share the development of the 'Making the case for biodiversity' strategy, its key findings and preliminary implementation.

Research methods and design

The 'Making the case for biodiversity' process was conducted during 2011 and combined stakeholder analysis, market research, engagement and facilitated dialogue.

An initial consultation and desk research phase comprised facilitated discussions and in-depth interviews with individuals representing the biodiversity sector, and basic research on how biodiversity has been communicated in South Africa and internationally. Following this phase, eight concept messages were developed for further testing. The eight messages each expressed a single concept, simply worded for immediate understanding, and were designed to motivate action (Table 1). Each message presented a different aspect of how biodiversity can be portrayed, and they are hence frames for biodiversity communications. Among the eight frames are several that appear consistently in global biodiversity communications (such as the message that biodiversity is our children's legacy), but also several that were developed using framing that is more locally relevant to a developing-world context (such as the message of biodiversity as a resource to the rural poor).

The process to test these communications frames began with an assessment of the relevant stakeholders that would form the target audience. A core focus group was assembled from SANBI and DEA staff and other advisors, who assessed a broad range of stakeholders based on their level of engagement in biodiversity issues and ability to influence decision making that influences biodiversity. This assessment helped to identify a potential target audience for biodiversity messaging that was primarily composed of different levels of government, parastatals, funding agencies and a few non-governmental organisations with a policy focus. Given DEA and SANBI's mandate for developing biodiversity policy at a national level, the target audience was identified as those organisations with a high level of national influence. This is the audience that DEA and SANBI are often required to interact with to implement national biodiversity policy.

The selected target audience informed the selection of individuals who would participate in the development and testing of biodiversity messaging. In-depth interviews were conducted with 18 representatives of the target organisations, to test the effectiveness of the potential messages. After general discussion of the messages, participants were asked to rank the messages by placing them in a pyramid shape, with the most compelling message at the top, the next two in the second row, and three in the third row. Messages were scored based on the ranking received.

The messages that were most effective were then further discussed at a two-day interactive conference attended by representatives of government and non-governmental organisations. This formed the basis of an integrated communications strategy for the biodiversity sector, called 'Making the case for biodiversity in South Africa', which detailed how best to interact with the target audience.

Results

The target audience was identified as stakeholders that have a high level of influence, but whose core mandate or business is traditionally seen to conflict with the objectives of the biodiversity sector. Their interest in the biodiversity sector results from seeing it as a perceived risk to their business and operations. The main source of competition is land use (including terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystems), which is a primary resource for both economic development and biodiversity conservation. Social and economic sectors also compete for budget, personnel and legislative priority from government. These 'competitors' include production sectors such as mining, agriculture, transport, electricity generation and their respective regulatory government departments.

The market research highlighted a number of ongoing debates that raise questions regarding the compatibility between biodiversity and production sectors, the validity of a business case for biodiversity, and how biodiversity conservation is related to historical inequities. For this reason, it became clear that communications must show how biodiversity can be seen as supporting sustainable development (Cadman et al. 2010) and must highlight the links between environmental degradation, poverty, ecosystem services and jobs (Blignaut et al. 2008).

Amongst wide-ranging responses to the communications frames tested, it became clear that the term 'biodiversity' and its link to economic development were poorly understood. In addition, biodiversity was often perceived as being associated with the wealthy or privileged, rather than the poor, and those in the biodiversity sector were thought to be out of touch with the everyday realities of a developmental state (DEA & SANBI 2011). There is often little evidence to support biodiversity messages in comparison with competing claims from other sectors such as mining or agriculture, that promise economic development and jobs (DEA & SANBI 2011). Furthermore, communication from the biodiversity sector is sometimes contradictory (e.g., differing opinions regarding the degree of compatibility between development and biodiversity). These perceptions need to be addressed by explicitly articulating the potential value of biodiversity to a developing society. The biodiversity sector needs a common, consistent narrative to change perceptions and replace confusion with clarity (DEA & SANBI 2011).

A particularly clear finding that emerged was the realisation that traditional biodiversity messaging based on 'fear of loss' was resulting in messaging fatigue and indifference amongst the target audience. Faced continuously with negative 'doom-and-gloom' messages, stakeholders were increasingly apathetic towards messages of threat and loss, and despondent in their ability to take action. Instead, the results showed that the biodiversity sector should endeavour to express the positive values of biodiversity that can inspire target audiences to action. In particular, participants felt that biodiversity messages should always emphasise the contribution that biodiversity can make towards societal and development objectives. As a result, each of the eight draft marketing messages (Table 1) included a clear value proposition.

The tested messages elicited a range of positive and negative responses from the interviewed stakeholders (Table 2). Strong appeal was associated with messages that were easy to understand, relevant to a developing economy and practical. Negative responses were evoked by messages with only a limited target audience, or that were vague or difficult to understand.

Ranking of the messages identified a clear winner (Figure 1). Portraying biodiversity as a national asset was the message considered to have the most potential to influence decision making. The response received for this message included opinions that it was appealing, convincing and relevant in the context of a developing country (Table 2). Developing countries have the opportunity to make sustainable biodiversity choices an important component of their development trajectory (Adenle et al. 2015), ensuring that ecosystem services such as clean water and food security contribute to economic development and social upliftment. The message of biodiversity as a national asset frames biodiversity as resource that can be quantified.

Messages also receiving high scores were children's legacy and practical solutions (Figure 1). Identifying biodiversity as our children's legacy appeals to the emotions, while retaining a strong link to sustainability science. The idea of intergenerational equity, and looking after opportunities for future generations, is already often used for marketing biodiversity (PIRC 2013). Practical solutions appeals to stakeholders who prefer action to theory. This message encompasses a range of practical measures that are ultimately achievable. The three top messages are not mutually exclusive, as any practical action towards valuing biodiversity as a national asset is likely to be beneficial to future generations.

Discussion

A strong theme that emerged from the market research was that biodiversity knowledge and understanding were lower than expected. This research was conducted in 2011, coinciding with the development of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, of which the first target recognises a global problem that low levels of biodiversity understanding result in undervaluation of biodiversity (CBD 2011). This finding is therefore consistent with low biodiversity awareness in other parts of the world. The biodiversity sector often forgets that others do not always understand its most commonly used terms (Saunders et al. 2006). This process showed that even the term 'biodiversity' was not widely understood in South Africa, despite the fact that South Africa is a megadiverse country, with substantial natural resources and a well-established ecotourism sector that contributes significantly to the economy. The links between biodiversity and economic development were shown to be even less well understood. Tittensor et al. (2014) show that biodiversity understanding in developed countries is likely to improve by 2020, contributing towards meeting Aichi Biodiversity Target 1, but that indicators of global interest in biodiversity and international development financing for environmental education show non-significant declines. Therefore, in developing countries in particular, there is still a strong need for widespread, basic biodiversity CEPA to improve understanding about the values of biodiversity. This will be most effective if communication is simple, with clearly defined and widely adopted terminology. It has been shown that well-defined ecological concepts, such as 'ecosystem services', have been valuable in encouraging transdisciplinary interest in ecology (Reyers et al. 2010).

The three top messages (national asset, children's legacy and practical solutions) correspond well with three important communication frames that should be considered when marketing biodiversity. The overall values of biodiversity are best expressed by including aspects of economic, emotional and practical value in communications (Table 3). A marketing campaign that targets aspects of each of these main frames towards appropriate audiences seems most likely to appeal to a wide number of stakeholders.

The idea of biodiversity as a national asset conveys its economic value (Table 3). It is easy to link biodiversity to economic and social development when using this message. Amongst many others, examples of this message include ecosystem services such as grazing and pollination for agriculture, estuaries as nurseries for the fisheries industry, and wetlands as natural water purification systems. The more emphatic communication of links such as these will demonstrate that biodiversity is critical to industry. This communication frame is likely to be particularly well suited to reaching a policymaker audience.

The monetary value of some ecosystem services has been estimated by widely varying measures (Le Maitre et al. 2007). In South Africa, a preliminary, though widely quoted, national assessment of the worth of ecosystem services estimated that they added R73 billion to the economy, or 7% of GDP in 2008 terms (DEA 2012). Values are likely to be higher than estimated as some factors, such as avoided loss of biodiversity (e.g. the value of reduced risk of natural disasters), are sometimes difficult to quantify. Although debatable, even the most conservative estimates attract the attention of decision-makers within government and business. Employment opportunities arising from conserving and utilising biodiversity are as important as the pure monetary value (Blignaut et al. 2008; EDD 2011). Proven financial benefits and job creation opportunities are able to gain attention and attract funding, particularly from government. Using the message of the economic value of biodiversity allows the biodiversity sector to compete with the messages from production sectors that offer employment and economic development. However, it also identifies the ways in which biodiversity may be relevant to industry, thus eliminating some of the perceived competition and creating opportunities for co-operation.

Not all of the value of biodiversity can be captured in purely economic terms; and there are those, usually in the biodiversity sector, who do not always agree with placing only a monetary value on Nature. It is important to emphasise that the concept of biodiversity as an asset is also compatible with other aesthetic, ethical and spiritual values of biodiversity. As others have cautioned (PIRC 2013), overstating the monetary value of nature can also oppose more meaningful, intrinsic values. Accordingly, biodiversity messaging should also emphasise alternative values for biodiversity, including the emotional, aesthetic, cultural, recreational, spiritual, symbolic, historical, ethical and other intrinsic values (Table 3). Emotional values are best captured in the message that biodiversity is our children's legacy. By preserving the wealth of biodiversity, we are leaving a legacy for our families and future generations. Ultimately, encouraging people, especially children, from a young age, to care for biodiversity on an emotional level makes them more likely to respect and protect the natural world (Balmford & Cowling 2006; Schwartz 2006). This frame is appropriate for public audiences, and should be linked to general biodiversity CEPA. For more formal audiences, this message can be made less sentimental by consciously linking it to sustainability science.

Finally, economic and emotional values mean little unless they are supported by practical considerations. The message of practical solutions (Table 3) provides the distinct steps that can be taken to achieve biodiversity objectives. Practical guidelines and decision-making tools, such as biodiversity priority maps and management plans, provide simple and easy-to-understand guidance on what actions are needed to better manage biodiversity. Any communications message should include guidance on simple actions that can be taken to protect and enhance biodiversity. Practical solutions increase the likelihood that the target audience will act on the message (Schultz 2011).

South Africa's 'Making the case for biodiversity' strategy (DEA & SANBI 2011) centres around a core communication frame encapsulated in the slogan 'Biodiversity: Powering the green economy' (Figure 2). This message is strong and simple, and makes the link to biodiversity benefits on economic, emotional and practical levels. As well as drawing strongly on the frame of biodiversity as a national asset, this core message also takes into account the international thinking and political context by utilising the United Nations Environmental Programme's definition of a 'green economy', as 'improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities' (UNEP 2011). It is also aligned with the notion that biodiversity can play a role in supporting economic development.

Policy uptake

The communications strategy was supplemented with an action framework (SANBI 2011a), detailing the channels through which the messages should be disseminated. The ideas of the 'Making the case for biodiversity' strategy were circulated amongst SANBI and DEA staff through several capacity-building workshops. These two organisations are leaders in the sector and are the most important role-players in applying the revised communication frames. Information was also shared with non-governmental organisations where possible. A toolkit was developed that indicated how to gather information, identify the target audience and present the information appropriately for that audience (SANBI 2011b). A primary focus of the toolkit was advice on writing effective biodiversity case studies (SANBI 2011b). Case studies are effective in strengthening the links between biodiversity and development. They offer narrative evidence that appeals to an audience on a personal level, while providing factual information and practical support for biodiversity initiatives. Case studies can be featured in local media to reach the public, or provided as a resource to targeted government departments. SANBI subsequently developed and distributed numerous case studies that followed the communication frames of the 'Making the case for biodiversity' strategy (SANBI 2015).

The 'Making the case for biodiversity' strategy has been instrumental in influencing national policy. The strategy helped to influence the Green Economy Accord (part of South Africa's New Growth Path), which originally only covered aspects of climate change and waste disposal, but now makes strong links to the value of biodiversity in developing a green economy that provides jobs and encourages rural development (EDD 2011). A significant aspect of the New Growth Path is the Strategic Integrated Projects, a set of 18 targeted infrastructure projects. The biodiversity sector is working with these massive infrastructure development ventures to integrate important aspects of biodiversity into their planning.

The findings of the market research process and implementation of the communications strategy were also significant in directing the biodiversity sector towards use of the concept of 'ecological infrastructure'. Ecological infrastructure is defined as 'naturally functioning ecosystems that deliver valuable services to people, such as fresh water, climate regulation, soil formation and disaster risk reduction' (SANBI 2013). The concept has gained interest from decision makers, as it aligns closely with the government's current strategy to encourage development in South Africa through built infrastructure. Investing in such 'ecological infrastructure' holds a promise for a return on investment through improved ecosystem services. Significant investments have been encouraged using the message of ecological infrastructure, particularly within the water sector. For example, the Water Research Commission has put out funding calls for multimillion Rand applied research grants into ecological infrastructure. The concept has also received attention from mainstream media and the target production sectors (e.g. a cover story in the popular industrial magazine Engineering News).

The strategy has been applied more broadly towards interactions with industry. Instead of adopting a mutually suspicious stance, the Birds and Renewable Energy Specialist Group and the wind farm industry recognised that they had a shared interest in the early-stage use of biodiversity information to site and design wind farms to minimise disruption of the turbines. Similarly, the highly influential Mining and Biodiversity Guideline (DEA, DMR, CoM & SANBI 2013) was developed through interaction with the industry-led South African Mining and Biodiversity Forum. The guideline is a practical tool with a spatial component for mainstreaming biodiversity into the mining sector, which helps to reduce business risk to the mining industry by proactively planning for biodiversity. In this way, the Mining and Biodiversity Guideline follows similar practical decision-making tools promoted by the International Council on Minerals and Mining.

A survey of the target audience, repeated after a year of implementing the strategy by distributing case studies and hosting discussions, showed an increased understanding of scientific terminology and higher awareness of biodiversity concepts, particularly those relating to ecosystem services and ecological infrastructure (ProEcoServe 2015). This finding indicates that the strategy is contributing to meeting Aichi Biodiversity Target 1 by improving basic biodiversity CEPA.

The findings of the market research echo the results of communications research elsewhere (Futerra 2010; PIRC 2013). The market research process and development of the 'Making the case for biodiversity' strategy provided confirmation that communication frames found to be effective in developed countries are also likely to be relevant in a developing-world context. More particularly in a developing country, clearly linking biodiversity messaging to economic growth, job creation and sustainability will better gain the attention of a policymaker audience. The process provided important insight into the target audience for South African biodiversity sector messaging, which will continue to guide both government and non-governmental organisations during their ongoing communications with important stakeholders. As implementing biodiversity objectives often involves the input of other stakeholders, an understanding of how best to frame communications to these potential partners is essential (Balmford & Cowling 2006). Such messaging assists the biodiversity sector in resolving debates that place biodiversity in conflict with socio-economic development (Saunders et al. 2006).

The biodiversity sector needs to change its approach to communications from a 'doom-and-gloom' message to a positive message that includes a clear value proposition for biodiversity that will inspire action. A strong biodiversity message should include aspects of economic and emotional values that provide motivation, accompanied by practical guidelines. If the sector embarks on a unified communications strategy, it is more likely that its messages will be heard and acted upon. Combined with biodiversity CEPA, social marketing is an emerging means for directing human behaviour towards a sustainable, biodiversity-inclusive future.

Acknowledgements

Helpful internal review comments were received from Phoebe Barnard and Colleen Seymour of SANBI.

The development of the communications strategy was made possible through the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) - Global Environmental Fund (GEF) funding to the Cape Action for People and the Environment (CAPE) and Grasslands Programmes. Implementation of the 'Making the case for biodiversity' project was enabled through the ProEcoServ project, funded by the GEF through the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and implemented in South Africa by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) and SANBI.

Conflict of interest

The South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) commissioned the preparation of the present paper and the research on which it is based. The stakeholder analysis and policy guidance were conducted by LinkD, a sustainable society consultancy. The market research was conducted by Freedthinkers, a market research and strategy company. Emily A. Botts was compensated by SANBI for providing writing and editorial support in preparing the paper for publication.

Authors' contributions

K.M. and M.B. were project leaders on the 'Making the case for biodiversity' project, run by SANBI. A.S. was involved in the 'Making the case for biodiversity' project as project manager of the Grasslands Programme. M.F. represents the consulting company that was appointed by SANBI to conduct much of the market research. E.B. was appointed by SANBI to prepare the paper for publication. L.G. assisted with revisions of the paper to provide communications theory expertise. All authors were involved in reviewing the manuscript.

References

Adenle, A.A., Stevens, C. & Bridgewater, P., 2015, 'Global conservation and management of biodiversity in developing countries: An opportunity for a new approach', Environment Science Policy 45, 104-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.10.002 [ Links ]

Balmford, A. & Cowling, R.M., 2006, 'Fusion or failure? The future of conservation biology', Conservation Biology 20, 692-695. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00434.x [ Links ]

Blignaut, J., Marais, C., Rouget, M., Mander, M., Turpie, J., Klassen, T. et al., 2008, 'Making Markets work for People and the Environment: Employment Creation from Payment for Eco-Systems Services', An initiative of the Presidency of South Africa, hosted by Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Borah, P., 2011, 'Conceptual issues in framing theory: A systematic examination of a decade's literature', Journal of Communication 61, 246-263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01539.x [ Links ]

Cadman, M., Petersen, C., Driver, A., Sekhran, N., Maze, K. & Munzhedzi, S., 2010, Biodiversity for Development: South Africa's landscape approach to conserving biodiversity and promoting ecosystem resilience, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. [ Links ]

CBD, 2011, Quick guides to Aichi Biodiversity Targets, Target 1: Awareness increased, Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, Canada. [ Links ]

DEA, 2012, State of play: Baseline valuation report on biodiversity and ecosystem services, Department of Environmental Affairs for The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

DEA & SANBI, 2011, Making the case for biodiversity: Final draft Project Summary Report, Department of Environmental Affairs and South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

DEA, DMR, CoM & SANBI, 2013, Mining and Biodiversity Guideline: Mainstreaming biodiversity into the mining sector, Department of Environmental Affairs, Department of Mineral Resources, Chamber of Mines, South African Mining and Biodiversity Forum, and South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

EDD, 2011, New growth path: Green economy accord, Department of Economic Development (EDD), Pretoria. [ Links ]

Futerra, 2010, Branding Biodiversity: The new nature message, Futerra Sustainability Communications, viewed 17 August 2015, http://www.futerra.co.uk/downloads/Branding_Biodiversity.pdf [ Links ]

Hesselink, F., Goldstein, W., Van Kempen, P.P., Garnett, T. & Dela, J., 2008, Communication, Education and Public Awareness (CEPA): A toolkit for National Focal Points and NBSAP Coordinators, Convention for Biological Diversity, Montreal, Canada. [ Links ]

King, B. & Pervalo, M., 2010, 'Coupling community heterogeneity and perceptions of conservation in rural South Africa', Human Ecology 38, 265-281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10745-010-9319-1 [ Links ]

Kepe, T., Saruchera, M. & Whande, W., 2003, 'Poverty alleviation and biodiversity conservation: A South African perspective', Oryx 38, 143-145. [ Links ]

Le Maitre, D.C., O'Farrell, P.J. & Reyers, B., 2007, 'Ecosystems services in South Africa: a research theme that can engage environmental, economic and social scientists in the development of sustainability science?' South Africa Journal of Science 103, 367-376. [ Links ]

PIRC, 2013, Common cause for nature: Finding values and frames in the conservation sector, Public Interest Research Centre, United Kingdom. [ Links ]

ProEcoServe, 2015, Improving awareness and understanding of the concept of ecological infrastructure through a targeted case study communications campaign, South African National Biodiversity Institute report for ProEcoServe, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Reyers, B., Roux, D.J. & O'Farrell, P.J., 2010, 'Can ecosystem services lead ecology on a transdisciplinary pathway?' Environmental Conservation 37, 501-511. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0376892910000846 [ Links ]

SANBI, 2011a, Biodiversity sector messaging strategy document: 2012-2015, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

SANBI, 2011b, Making the case for biodiversity the biodiversity case study development toolkit, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

SANBI, 2013, Ecological infrastructure factsheet, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

SANBI, 2014, Biodiversity Mainstreaming Toolbox for land-use planning and development in Gauteng. Compiled by ICLEI - Local Governments for Sustainability for the South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

SANBI, 2015, Ten compelling case studies making the case for biodiversity, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa, viewed 8 November 2015, from http://www.sanbi.org/news/ten-compelling-case-studies-making-case-biodiversity [ Links ]

Saunders, C.D., Brook, A.T. & Myers, O.E., 2006, 'Using psychology to save biodiversity and human well-being', Conservation Biology 20, 702-705. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00435.x [ Links ]

Schultz, P.W., 2011, 'Conservation means behaviour', Conservation Biology 25, 1080-1083. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01766.x [ Links ]

Schwartz, M.W., 2006, 'How conservation scientists can help develop social capital for biodiversity', Conservation Biology 20, 1550-1552. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00421.x [ Links ]

Snyman, S., 2014, 'Assessment of the main factors impacting community members' attitudes towards tourism and protected areas in six southern African countries', Koedoe 56(2), 12 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/koedoe.v56i2.1139 [ Links ]

Tittensor, D.P., Walpole, M., Hill, S.L.L., Boyce, D.G., Britten, G.L., Burgess, N.D. et al., 2014, 'A mid-term analysis of progress toward international biodiversity targets', Science 346, 241-244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1257484 [ Links ]

UNEP, 2011, Towards a green economy: Pathways to sustainable development and poverty eradication. United National Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya. [ Links ]

Veríssimo, D., 2013, 'Influencing human behaviour: an underutilised tool for biodiversity management', Conservation Evidence 2013, 29-31. [ Links ]

Wilhelm-Rechman, A. & Cowling, R.M., 2011, 'Framing biodiversity conservation for decision makers: insights from four South African municipalities', Conservation Letters 4, 73-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2010.00149.x [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Kristal Maze

k.maze@sanbi.org.za

Received: 18 Nov. 2015

Accepted: 19 Oct. 2016

Published: 03 Dec. 2016