Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)

On-line version ISSN 2520-9868Print version ISSN 0259-479X

Journal of Education n.97 Durban 2024

https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i97a12

ARTICLES

Evolution of classroom languaging over the years: Prospects for teaching mathematics differently

Jabulani SibandaI; Clemence ChikiwaII

IDepartment of Human Sciences, Faculty of Education, Sol Plaatje University, Kimberley, South Africa. Jabulani.Sibanda@spu.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5328-5888

IIDepartment of Natural Sciences and Technology, Faculty of Education, Sol Plaatje University, Kimberley, South Africa. Clemence.Chikiwa@spu.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5638-6131

ABSTRACT

In this theoretical paper, we trace diverse language practices representative of equally diverse conceptions of language. To be dynamic with languaging, one should appreciate nuanced languaging practices, their challenges, and prospects. Here, we present what we envision as three major conceptions of language that give impetus to diverse language practices. We examine theoretical models of the bilingual mental lexicon and how they inform languaging practices that have been promulgated and experimented with over the years. We proceed on the premise that interactive and dynamic languaging depends on one's nuanced beliefs, assumptions, and understandings of the concept of language, how languaging has evolved over the years, and the diverse learner profiles and the linguistic resources they bring. Because languaging is an evolving phenomenon, it is disruptive and fluid since it responds to the complexities of human experience and socio-cultural, technological, and environmental shifts characterising those experiences. Languaging offers prospects for creativity and innovation, as well as linguistic flexibility. Using mathematics as a proxy for languaging, we advocate for the deployment of multisensory semiotic systems to complement linguistic classroom communication and an acknowledgment of the validity of learners' linguistic and semiotic resources in the learning enterprise. We demonstrate how many different linguistic, semiotic, and symbolic resources converge in classroom languaging, and how dynamic languaging has a constant and dialogic shift between and among known languages, and between formal and informal language in a fluid nature. We recommend the enactment of specific multimodal languaging clauses in education policies and curriculum documents that empower classroom interactants to exercise discretion in languaging practices.

Keywords: languaging, monolingual, multilingual, semiotic and linguistic repertoire

Introduction

In this paper, we trace the evolution of classroom languaging in multilingual English as Second Language (ESL) contexts. Understanding various languaging practices and their challenges is instructive to their effective use in educational settings. We explore different conceptions of language in the context of theoretical models of the bilingual mental lexicon, and how they inform diverse classroom languaging practices. We propose prospects for using many different linguistic and semiotic resources for effective languaging in mathematics classrooms as a proxy for other content disciplines characterised by "the multiplex linguistic networks" (Sibanda, 2021, p. 20). We contribute to the theoretical understanding of languaging practices in multilingual ESL classroom contexts, the complexity of language use in educational settings, and prospects for positively disrupting classroom languaging practices.

Classroom language practices can constitute systemic barriers for learners according to Zwiers et al. (2017), can make or break interactional patterns, and influence academic outcomes. Classroom languaging has been characterised by an expansive range of terms depicting language alternation practices, that transcend mere popularist neologism or sloganisation (Wei & Lin, 2019) whose nuanced and intricate distinctions are beyond the scope of this paper. The tracing of languaging practices in this paper is not meant to be chronological since languaging practices predate their nomenclature.

Method

We used desktop research on classroom languaging to review and synthesise publicly available data without collecting or generating any primary data. The research was guided by the following questions:

• What gives impetus to languaging practices in multilingual classroom contexts?

• Which languaging practices have been deployed in multilingual contexts and to what effect?

• What constraints militate against the positive disruption of extant languaging practices and what prospects exist?

• How can languaging be employed in mathematics multilingual classrooms to empower interactants?

The questions constitute the organising framework for the findings.

Theoretical framing

We explore two aspects of the impetus to languaging practices on: languagers' conception of language(s), and the assumptions of the bilingual mental lexicon. These are discussed in turn.

Languagers' conception of language(s)

We present three conceptualisations of language(s): language as an ideological (not real) phenomenon; language as a distinct, fixed, immutable object; and language as a fluid phenomenon (determined by use). We envision the first two as extreme points on a continuum and the third as a mid-point that strikes a compromise between the two extreme conceptions on the continuum.

Language as an ideological not real phenomenon

An extreme view of language as an ideological and not a real phenomenon is that "there is no such thing as Language, only continual languaging" (Becker, 1991, in Wei & Lin, 2019, p. 210). This view denies the existence of languages as discrete and enumerable categories and sees them as merely convenient, social, political, ideological constructions with fuzzy boundaries born out of historical antecedents. Humans, in this view, supposedly merely adapt and orient themselves to languaging practices exposed to them. In this conception, "languageness and the metalanguages used to describe them are inventions" (Makoni & Pennycook, in Makoni & Pennycook, 2007, p. 1) "located in Western linguistic and cultural suppositions" and not amenable to a science of language (p. 27). Language boundaries are seen to be arbitrary and a human creation devoid of any social or functional reality or justification, with linguistic criteria unable to account for the demarcations. This non-materialistic view of language attributes physical existence to languagers, not languages, which equates to denying structure and regulation.

Language as a distinct, fixed, immutable object

The view of language as a distinct, fixed, immutable object is the other extreme and purist view that reifies languages and gives them status as natural, distinct, monolithic, a priori, and immutable objects whose structure and purity are sacrosanct and need to be guarded. Languages are perceived as carrying the burden of meaning-making through the rigors of scientific analysis without recourse to semiotically mediated lived communicative activity in meaning-making. This view constrains linguistic alternation and is tantamount to linguistic tyranny reminiscent of the age-old Saphir-Whorf hypotheses of linguistic determinism and linguistic relativity (Whorf, 1956). This view constraints language alternation practices. Childs (2016, p. 24) aptly observed that "[t]eachers operating with an understanding of language as a bounded and pure system may struggle to accommodate learners who cannot use the target language required for learning and teaching effectively."

Language as a fluid phenomenon

A midway view that eschews both extremes is of language as a fluid phenomenon determined by use. It acknowledges the existence of languages as countable, unitary, and separate entities, which are, however, not overly codified, structured, and fixed, but are in a perpetual state of creation and accommodation to meet users' communication needs. A structuralist appraisal of inherent structural configurations of languages is subordinated to use in meaning making, which imbues languages with power and realness. The measure of stability engendered by linguistic signs dialectically interacts with the instability and unpredictability of communicative contexts and activities. Individuals may even embody unique and varied repertoires or idiolects, testimony that linguistic features and codes are not ready packages for languagers to extract and apply.

"The tension between rarefied views of language as hermetically sealed entities found in language policies and practices that emerged from the late 19th-century Europe on the one hand, and a recognition of the more fluid use of language in multilingual settings in Africa on the other hand" (Heugh, 2015, p. 281) is reflective of the language as object and language as a fluid phenomenon.

Over and above classroom languaging being a product of educators' conceptions of language, as shall become apparent later, it also stems from educators' assumptions of how bilinguals process language courtesy of their mental lexicon.

Theoretical models of the bilingual lexicon

There has been a marked departure by linguists and psycholinguists from perceiving language processing based solely on separate languages. Progressively, "various linguists and psycholinguists describe language processing beyond naïve ideas of separate languages." (Prediger et al. 2019, p. 191). The conceptions of the bilingual lexicon are captured in the models below.

The word association model envisages L2 access to the semantic or conceptual system occurring only via the mediation of the L1. In the concept mediation model, the assumption is that the bilingual's L1 and L2 features have direct access or correspondence to the semantic or conceptual system. The revised hierarchical model not only posits an L1 and L2 with direct access to the semantic or conceptual system, but also intimates an L1 to L2 direct and bi-directional connection, where lexical connections are hypothesised to be stronger from L2 to L1 than from the L1 to the L2. The asymmetrical model (not in the figure) postulates that L2 to L1 associations are stronger than the reverse association. Sandberg et al. (2021, p. 2) posited that "the link from L1 to the semantic system is stronger than the link from L2 to the semantic system, and the lexical link from L2 to L1 is stronger than the lexical link from L1 to L2." Apart from the concept mediation model, these models posit that the bi-multilingual's repertoire does not consist of two or more inflexible solitudes, but a single unitary lexicon. The brain has an affinity and capacity for engagement with, and coactivation of, multiple languages. For Prediger et al. (2019, p. 192) "codes are complementarily functional."

From these models can be mapped diverse conceptions of the bilinguals like balanced bilinguals (who have equivalent mastery in both languages), dominant bilinguals (with greater proficiency and use of one language), incipient bilinguals (with still developing proficiency in both), maximal bilinguals (with near native-like competence in both languages), minimal bilinguals (with little understanding of the second language), functional bilinguals (having full proficiency in the two languages for a task at hand), receptive bilinguals (who understand the other language but have difficulties speaking it), productive bilinguals (who can decode and encode in both languages), and recessive bilinguals (who have difficulties with expression) (Hummel, 2020).

Functional imaging experiments do not provide conclusive data on how bi/multilinguals determine which language to employ where and when, seeing that the brain regions activated are the same notwithstanding which language is employed. In encoding communication, all known languages are activated. Van Heuven et al. (2008, p. 2706) posited that

Activation of the first (L1) and second (L2) language in bilinguals and the occurrence of language conflict might depend on specific language combinations, proficiency of the bilinguals, the language context (purely L1 or L2, or mixed), input/output modality, task demands, and/or instructions.

Language conflict occurs when both the L1 and the L2 are activated, and instead of selecting words from the target language, the non-target language word is selected.

A monolingual, monoglossic, or fractional conception of language fails to appreciate the complexity of bilinguals' discursive practices, assuming that the bilingual is two monolinguals in one person ". . . with access to two detached language systems that develop in a linear fashion and are assessed separately from one another" (Sibanda, 2021, p. 29).

Findings

In this section we discuss what we envision as major languaging practices over the years, starting with practices consonant with language as a fixed entity conception.

Mono-languaging practices

It is important to acknowledge that "despite the theoretical appraisal in recent years of the importance of L1 in learning additional languages, the target-language-only or one language-at-a-time monolingual ideologies still dominate much of practice and policy, not least in assessing learning outcomes" (Wei, 2021, p. 16). Where the dominance is rationalised based on the Language of Learning and Teaching (LoLT) being the only one the teacher and students have in common, monolingual practices serve the teacher's convenience rather than learners' benefit. It positions the teacher as the arbiter of classroom communication and invalidates linguistic practices that are not teacher mediated.

In second language teaching methodology, the Direct Method or Natural Method, an antithesis and repudiation of the Grammar Translation Method (GTM), is reflective of monolingual practices that have no recourse to learners' Home Languages (HLs). The teacher and learners would rather employ pantomimes, visuals, exemplification, gestures, demonstration, dramatisation, and other paralinguistic and extralinguistic features than use the HL. Assessment regimes are largely monolingual. Guzula et al. (2016, p. 2) observed that monolanguaging "continue(s) to dominate officially prescribed language teaching and learning approaches, curricula, policy, and materials in South African education." In South Africa, as in many former British colonies, Anglonormativity accounts for monoglossic approaches, legitimation of English, and stratification of languages in favour of English. Another practice consonant with the view of languages as bounded entities is translation.

Translation as a languaging practice

Translation is a reactive or responsive repetition of an utterance in the language learners find accessible. Despite having been consigned largely to the annals of language teaching history, there has been a revival of translation as both a contested but unavoidable languaging practice (Beiler & Dewilde, 2020). As a classroom languaging practice, translation has not quite caught on owing to some grave limitations on its part. Its association with the GTM is among the factors responsible for its undoing since GTM emphasised automatic rather than communicative translation. It erroneously presupposes equivalence and direct correspondence between the languages involved, even non-cognate languages. Its assumption that the L2 can be accessed through the L1 prism without regard for interference, where thinking is done in one language and translated to another, adds to its limitations. What we see as its greatest limitation is its lack of authenticity since people generally do not translate generally in real discursive practices.

Despite these limitations, it has been hailed for developing competence in both languages, as well as multilingualism and intercultural competence (González-Davies, 2017). Code switching, like translation and monolingual practices, has its basis in an ideological concept of language as a closed entity.

Code switching

Code switching is based on the notion of two or more distinct languages existing in the bilingual's mind. According to Childs (2016, p. 25), "Code switching is usually a relatively short move from the LoLT to the home language of learners and then a switch back to the LoLT." It represents a temporary and largely reactive excursion or detour from the base or matrix form within a monolingual so-called ideal. While code switching acknowledges the need to alternate language codes meaningfully, the codes still need to be official or standard ones. The practice retains monoglossic ideologies based on an assumption of the bilingual mind being characterised by internal language-specific differentiation (MacSwan, 2017). We consider the structural differences of the languages involved.

Wei (2021, p. 167) claimed that "[c]ode switching . . . pays more attention to the structural differences between named languages, and a code-switching analysis would start by identifying how many languages are involved and what they are." The base form is unmistaken since the detour to the other language is brief. Code switching privileges one language (the base, matrix, or dominant) over the other, to which the interlocutors occasionally gravitate. Code switching is alternation of languages not mere translation of words, meanings, conventions, or linguistic and semiotic systems.

Code switching has its basis in a deficit view of the LoLT, and functions as a repair mechanism meant to mask linguistic and/or memory deficiency in the matrix language (Wei & Lin, 2019), which does injustice to the less dominant language, and indexes weakness rather than strength. Monolingualism is foregrounded as the ideal and code switching is just meant to repair communication. It also limits the scope of alternation largely to the sentential level. The orthographic or structural distance between languages, characteristic of African languages vs English can render code switching untenable. Much of classroom code switching is unprincipled and a reserve of oral communication. The languages involved play different roles and retain their distinct identities. An ethnographic study in Sweden "found that English was typically used for 'on-task' discussions while the L1 was used for closed discussions between L1 speakers" and "that code-switching occurred most commonly for single word translations" (Sahan & Rose, 2021, p. 47).

There is ambivalence on whether code switching is a regulated practice. However, in most cases, "Code-switching is normally employed in an ad hoc, spontaneous, unpremeditated, relatively brief, reactive way within a largely monolingual orientation" Sibanda (2021, p. 29). The breadth and level of its regulation, whether general or atomistic, has not been well established. Languaging that starts to depart from a monoglossic structuralist view of language into a more integrationist ideology is poly-languaging.

Poly-languaging

In a polylingual context, linguistic features at interlocutors' disposal are deployed in a communicative event without regard to interactants' proficiency in the languages from which the features derive, leading to hybrid linguistic features. The meshing of features is largely random and arbitrary but can also be rational. Features of speech are the focal point in poly-languaging, not languages, and they do not warrant advanced proficiency for their use. Chat languaging exemplifies how languagers thrive on the deployment of available resources without regard to the artificial boundaries imposed by languages. Polylanguaging's emphasis is on the involvement of a multiplicity of languages in a discursive context. While the language boundaries are recognised and acknowledged, polylanguaging "tends towards a pluralisation of singular entities (languages)" (Otsuji & Pennycook, 2010, p. 247). The plurality the practice romanticises has its basis in languages being countable phenomena that can be catalogued, and whose boundaries are not merely putative but real and fixed. Translanguaging endeavours to make a significant departure from a diglossic compartmentalisation towards hybridisation of linguistic repertoires in heteroglossic practices in translanguaging.

Translanguaging

While in code switching languages are compartmentalised, in translanguaging they are dynamic, fluid, intersecting, and overlapping entities. While polylanguaging relates to importing many boundaried languages into a communicative event, translanguaging seeks to dismantle, ignore, or de-emphasise language boundaries, and so does not require proficiency in languages to which linguistic repertoires used can be attributed. In translanguaging, the mind is visualised as an integrated whole, where known linguistic systems are not compartmentalised into languages, but are drawn from a unified whole (Li, 2017). "The myriad linguistic features mastered by bilinguals (phonemes, words, constructions, rules, etc.) occupy a single, undifferentiated cognitive terrain that is not fenced off into anything like the two areas suggested by the two socially named languages" (Otheguy et al., 2019, p. 625). Focus shifts from structural systems to participation.

The affixes in translanguaging are instructive. 'Trans -' signifies transcending the limitations and boundaries of named languages through fluid leveraging of semiotic resources (Zein (2022). The "-ing suffix urges us to focus on the momentariness, instantaneity and the transient nature of human communication" (Wei & Lin, 2019, p. 211). The more widespread the acceptance of translanguaging, the more it develops both nuanced and alternative meanings not originally intended. Most definitions of translanguaging endorse the existence of language boundaries but posit that they are imposed and unnatural, rather than psychological or linguistic, and can be transcended strategically. The shuttling or vacillation between and among languages is done oblivious to their socio-political boundaries. Discursive practices do not recognise the boundaries as psychological or linguistic. According to Goodman and Tastanbek (2020, p. 7), ". . . multilingual minds could still clearly differentiate the language boundaries and cross them strategically upon necessity in spite of having a unitary semantic repertoire." However, translanguaging definitions like "the dynamic use of multiple languages to enhance learnings" (MacSwan, 2017, p. 191) are not sufficiently disruptive to negate the reality of languages or debunk them. They simply render the language frontiers porous. In this conception, teaching for cross-linguistic transfer is considered a precursor to translanguaging.

The radical or strong view sees individuals as possessing unique idiolects that can neither be reduced to regularisation and standardisation, nor attributed to named languages. Translanguaging is heteroglossic and humanising in its acknowledgement of the full range of linguistic and semiotic resources learners bring to the communicative event, which eschews linguistic inequality. In this conception, "Rather than categorising languages as discrete entities, translanguaging frames language use as a performative act in which users construct and interpret meaning based on the resources available in their linguistic repertoires" (Sahan & Rose, 2021, p. 45).

Translanguaging opens spaces for multimodality, creativity, hybridisation, and fluid discursive practices, and validates learners' full linguistic, multimodal, and semiotic repertoires otherwise considered deviant. "Imposing one school standardised language without any flexibility of norms and practices will always mean that those students whose home language practices show the greatest distance from the school norm will always be disadvantaged" (García et al., 2011, p. 397). Translanguaging's deployment of creative and hybrid linguistic, non-linguistic, and semiotic resources hybridises, diversifies, revitalises and transforms linguistic practices and culminates in a novel discursive repertoire. Translanguaging needs corresponding trans-semiotisation to accommodate its multilingual, multifaceted, multisensory, and multisemiotic nature. Inclusion of non-linguistic resources, whether paralinguistic or extralinguistic, and traversing codes in ways that celebrate learners' diverse multilingual identities, eschew lingua bias in the classroom. Translanguaging sanitises much of what was regarded deviant, unacceptable, language corruption, erroneous, or illegitimate.

There is ambivalence about whether translanguaging practices can be taught or are natural to children. The latter finds credence in children's affinity to adapt own language mixing to audience and context. In favour of the former, "[t]he preponderance of spontaneous rather than strategic pedagogical use of translanguaging suggests that teachers and teacher educators . . . need to be explicitly taught ways to incorporate heteroglossic ideologies and intentional translanguaging pedagogies into their teaching practice" (Goodman & Tastanbek, 2020, p. 1) Vallejo and Dooley (2020, p. 9) made an apt observation that "classroom-based research indicates that, while teachers are generally favourable to opening spaces to students' plurilingual practices . . . to be used as scaffolding tools while carrying out school tasks, there is still extended resistance to adopting these practices as outright teaching resources." This explains why translanguaging has been the preserve of oral discussions during teaching and not part of formative and summative assessment, bringing disjuncture between teaching and assessment.

Trans-semiotisation

Trans-semiotisation accounts for many meaning-making signs that coalesce and homogenise to comprise an interlocutor's semiotic repertoire. It amalgamates the linguistic with diverse semiotic representations to broaden one's repertoire and enhance communication. Mathematics lends itself well to the deployment of many semiotic systems in its highly symbolic form and visual representation of information, and other multimodal resources. The nexus between translanguaging and trans-semiotisation in mathematics classroom communication needs much exploration. Chen, et al. (2022, p.2) noted,

In a classroom, trans-semiotizing mainly takes the form of shuttling between visuals, prosody, gestures, bodily movement, and others in face-to-face interactions . . . in online contexts, it takes the form of shuttling between text messages (i.e., texts), emojis, pictures, voice recordings (i.e., audio), and other forms of interaction.

Metrolingualism

Societies are progressively urbanising and modernising, and metrolingualism stems from the modern and largely urban interaction of those from diverse and mixed backgrounds that serve largely as an identity marker. In metrolingualism, language is a conventionalised activity whose norms can be broken. "Metrolingualism focuses on the production of relations across language, culture, ethnicity, and geography that are emergent in certain places and moments as people draw on available semiotic resources to engage in local activities" (Yao, 2021, p. 3). Urbanity shapes metrolingualism as meaning emerges from contextual interaction through an assemblage of an array of multimodal and semiotic resources from the perspectives of the languagers, oblivious of regulation. Metrolingualism "refers to creative linguistic conditions across space and borders of culture, history and politics." It transcends language frameworks "providing insights into contemporary, urban language practices, and accommodating both fixity and fluidity in its approach to language use" Otsuji and Pennycook (2010, p. 240). Contemporary cosmopolitan cities have proven that interlocutors defy linguistic boundaries as they use and deploy all mutually intelligible semiotic systems to interact and communicate.

What we have discussed are a few languaging practices. The question that remains is what now for languaging in general, and in the mathematics classroom in particular?

Way forward

Prospects for languaging in general

Classrooms are linguistically complex contexts where, on the one hand, there is need for diverse languaging practices and, on the other, "linguistic and orthographic distance compromise the deployment of diverse linguistic resources" (Sibanda, 2021, p. 19). Pluralised monolingualism (double or multiple monolingualism) still reigns in classroom discourse and the persistence of conflict between language policy pronouncements, ideal languaging practices of the classroom, and the real daily classroom languaging practices is palpable (Sibanda, 2017). There is need for a shift from discourses framed around languages (a reserve of linguists) to those framed around communication (the concern for teachers). That would contribute to a disinvention of language as a fixed immutable entity, and its reinvention as an activity for use and meaning creation. Disinvention is requisite if we are to eschew reproducing traditional conceptions of languages that at best lead to a pluralisation of monolingualism (Makoni & Pennycook, in Makoni & Pennycook, 2007, p. 22). In assessment regimes, output need not be restricted to the linguistic mode, but may transcend to the visual, gestural, spatial, among other modes.

In pedagogical translanguaging, the onus is on the teacher to determine the linguistic and semiotic resources to be deployed in the classroom. Whether teachers are not conversant with particular linguistic resources, their task is to appreciate and accommodate the diverse linguistic, non-linguistic, extra-linguistic, multimodal, and multisemiotic discursive practices learners bring to the classroom context and learn from them. "The teacher needs to justify his or her presence by guiding learners in the voyage, not only of discovery, but more importantly, of creation" (Sibanda & Marongwe (2022, p. 60). However, pedagogical translanguaging does not depart from the acknowledgement of languages as separate, sacrosanct, truncated units, thereby promoting pluralised monolingualism.

Extant language policies should embrace the language continuum and linguistic mosaic in multilingual classrooms. Translanguaging's popularity does not equal ease of navigation since "focus is not on merely synthesizing or hybridizing diverse language practices (as languaging transcends a system of rules or structures) but crafting novel language practices that complexify linguistic discourses among interlocutors" (Sibanda, 2021.p. 35).

As a hybrid urban variety, Kasi-taal is almost developing into some learners' home language and demolishes linguistic boundaries in proximal or cognate indigenous African language varieties. The efficacy of importing such linguistic resources and creativity into orthographically and structurally distant linguistic codes merits exploration. A definition of translanguaging that restricts the practice to cognate traditional linguistic codes downplays the effect of international migration and translocal movements that accord learners linguistic resources from diverse and widely dissimilar languages.

Languaging in the mathematics classroom

As has been noted, "Mathematics education begins in language, it advances and stumbles because of language, and its outcomes are often assessed in language" (Durkin 1991 in Botes & Mji (2010, p. 123). In the mathematics classroom, learners often grapple with the English language, which is often not their home language, as well as with the highly symbolic, abstract, and formulaic mathematical language characterised by concision, precision, power, and dense jargon that confounds even the home language learners. Mathematical discourse practices of explaining, conjecturing, and justifying should take precedence over both the linguistic and computational forms since precision is more in the discursive practices and not the linguistic or computational.

Translanguaging pedagogies hold the promise of "bridging out-of-school knowledge and experiences with the mathematical understandings students are expected to learn in school" and the flexible language practices "offer unique affordances for rich mathematical discourse" (Marshallet al., 2023, p. 2). The traditional framing of multilingualism as a problem emanating from a deficit perspective needs to give way to a framing of multilingualism as a classroom asset facilitative of productive engagement in a discipline.

In monolingual practices, teachers tend to compensate for the lack of recourse to their Home Language by overly simplifying the LoLT to the point that the simplification compromises and even obscures access to rich mathematical content. Simplification reduces the linguistic cognitive demand of mathematics by exempting learners from: challenging words or phrases; making mathematical explanations, reasoning, assumptions, conjectures, and arguments; critiquing others' reasoning; drawing generalisations; collaborating in task completion; reasoning abstractly; expressing own emerging mathematical ideas; or comparing methods and representations. This could stem from an ill-conceived notion of mathematics as largely semiotic and restricted to computation, with minimal demands of a linguistic nature. Amplification is preferrable since it anticipates potential challenges with accessing mathematical concepts, and proactively accords many multimodal, multi-semiotic languaging practices and pathways responsive to the nature of mathematical activity and transcending monolingual practices. [T]eachers can foster students' sense-making by amplifying rather than simplifying, or watering down, their own use of disciplinary language" (Zwiers et al., 2017, p. 6).

One common misconception is the monolithic view of mathematical discourse as exclusively formal and not social. An apt example of social mathematical discourse is how, in everyday use, the word half is synonymous whether the two parts are unequal, or thirds, or quarters. This social, everyday mathematical discourse, and its ambiguity and multiplicity that learners are accustomed to, should be the springboard from which formal language is developed. Real mathematical discourse will be found at the intersection of these interdependent and dialectical discourses, rather than in their needless reification as mutually exclusive.

Restriction of mathematical discourse to procedural discourse focused on the manipulation of conventional symbols yields correct answers but does not guarantee conceptual mastery since there is not much extended discourse incorporating the broad range of learners' linguistic and semiotic capital or funds of knowledge. Mathematical discourse is rendered superficial and robbed of its potency for the development of thought when all it expresses is procedural computations and notation. Unscripted discussion, exploration, negotiation, justification, and sharing of knowledge is lost sight of and the claim is often made that the other languages are not sufficiently codified to express the computational and procedural discourse of mathematics.

Diverse linguistic resources embody diverse skills and experiences that bridge the disconnect between mathematics and learners' lived experiences. Mathematical argumentation, reasoning, and justification should take pre-eminence over accuracy, and the obsession with the correct answer should give way to privileging quality and robust engagements where learners are flexible to draw from their varied linguistic and semiotic repertoires. Accuracy would then be a by-product and not an end. The mathematics classroom should be characterised by multimodality (receptive and productive modes), multi-representation (graphic, semiotic, pictorial, gestural, tabular, linguistic, spatial etc.), among other diversities like audience, text types, talk types, degrees of formality, and levels of complexity, thus catering for the full spectrum of mathematical activities. Flexible assessment should cater for such diversities and shift from the traditional written timed reproduction of facts (accuracy) to focus on mathematical thinking and participation in mathematical discourses.

While mathematical computations are generally static, absolute, and precise, discourse about them is dynamic, evolving, imprecise, varied, plural, and complex. Rinneheimo and Suhonen (2022, p. 175-176) cite Kilpatrick et al. in relation to the (2001) five components as mathematical proficiency being

• conceptual understanding - comprehension of mathematical concepts,

• procedural fluency - the ability to engage in flexible, efficient, accurate and appropriate calculation,

• strategic competence - problem solving,

• adaptive reasoning - ability to engage in logical thinking, reflection, explanation and justification, and

• productive disposition - habitual inclination to see mathematics as sensible, useful, and worthwhile, coupled with a belief in diligence and one's own efficacy.

Such complex practices require an engaged and engaging mathematical discourse that deploys the full range of learners' repertoires in mathematical symbolic language, natural languages, and pictorial language.

The mathematics classroom is not exempt from languaging dynamics that may account for discontinuities in understanding, especially where there is much distance between learners' home languages and the LoLT. In the South African context, the main language is not the LoLT for most learners. Further complication of the languaging dynamics in the mathematics classroom is occasioned by the distinction between mathematical register (with its elaborate forms at all the levels from the morphological to the discourse) and ordinary linguistic register.

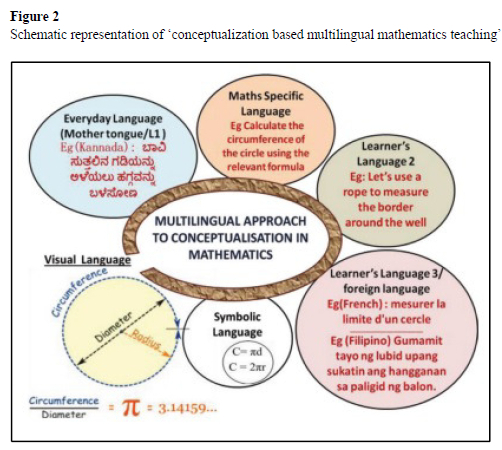

Linguistic support for students learning mathematics in a language that is not their home language should be deliberate and explicit (Kahiya & Brijlall, 2021). These scholars encouraged the deployment of many language types in informal talk and formal mathematical talk. While we proscribe the home languages to informal talk and the LoLT to formal mathematical talk, we envision an overlap between the two and, therefore, advocate a fluid deployment of learners' linguistic resources in both informal and formal talk. Progression should also not be prescriptive and linear from informal to formal talk but should be unidirectional and fluid even to the point where labelling one language as the LoLT becomes a misnomer. We concur with Kahiya and Brijlall (2021) on the need to strike a balance between using the home language in conceptual understanding of mathematics without oversimplifying the language of instruction to the point where it obscures mathematical concepts. Language use should be facilitative of mathematical reasoning and engagement with mathematical complexities, whether informally or formally, in the home language, the LoLT, or both. The assumption that only the LoLT is capable of formal mathematical discourse is both unfounded and counterproductive since it is seeing the two as mutually exclusive. Rather than posit a tension between formality and informality and between the home language and the LoLT, the boundaries (if any) are porous and dialogic. The same porosity exists between the spoken and written mathematical discourse. Ethnomathematics has been proposed as a way of bridging the gap between formal and informal mathematics when the existence of that chasm should not even be envisioned within fluid mathematical languaging. Bairy's (2019, p. 74) schematisation of the confluence of languages in Figure 1 below is instructive.

For us, the schematisation represents an onslaught on mathematical concepts through deploying a cocktail of linguistic and semiotic meaning-making resources. Bairy (2019, p. 74) posited that "[p]lurilingualism, the interconnected knowledge of multiple languages, is seen as a catalyst for creative learning in today's super-diverse society." It capitalises on linguistic diversity and the link among unique linguistic features. The quality of mathematical tasks will ensure productive mathematical talks. Even initiatives like Realistic Mathematics Education (RME) that thrive on problem-solving, critical thinking, and analytic skills (Van den Heuvel-Panhuizen & Drijvers, 2014), depend on the deployment of all the learners' linguistic and semiotic resources. The RME uses real-world problems to develop mathematical concepts, and the language learners can access and communicate the fact that reality needs to be deployed in their learning. Progression is from real-life contexts that are mathematisable to abstractions, not the other way around. The home language and LoLT can be deployed in both the mathematisation of real-life contexts or their abstraction.

Conclusion

We conclude that sound languaging is dependent on understanding the nuances of languaging in multilingual ESL classrooms, and the use of many linguistic and semiotic resources can enhance classroom interactions. Such languaging allows learners to draw on their full linguistic repertoires, eliminates language barriers, creates an inclusive and interactive learning environment, facilitates language acquisition, and cognitive, and academic development. This transforms multilingual classrooms into rich, effective, inclusive but diverse learning spaces. We recommend the incorporation of specific clauses on languaging in education policies and curriculum documents to empower teachers and students in their languaging practices.

References

Bairy, S. (2019). Multilingual approach to mathematics education. Issues and Ideas in Education, 7(2), 71-86. https://doi.org.10.15415/iie.2019.72008 [ Links ]

Beiler, I. R., & Dewilde J. (2020). Translation as translingual writing practice in English as an additional language. The Modern Language Journal, 104, 533-549. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12660 [ Links ]

Botes, H., & Mji, A. (2010). Language diversity in the mathematics classroom: Does a learner companion make a difference? South African Journal of Education, 30(1), 123-128. https://doi.org/10.4314/saje.v30i1.52606 [ Links ]

Chen, Y., Zhang, P., & Huang, L. (2021). Translanguaging/trans-semiotizing in teacher-learner interactions on social media: Making learner agency visible and achievable. System, 104, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102686 [ Links ]

Childs, M. (2016). Reflecting on translanguaging in multilingual classrooms: Harnessing the power of poetry and photography. Educational Research for Social Change, 5(1), 2240. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2016/v5i1a2 [ Links ]

García, O. (2019). Translanguaging: A coda to the code? Classroom Discourse, 10 (3/4), 369-373. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2019.1638277 [ Links ]

Garcia, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism, and Education. Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.10.5565/rev/jtl3.764

García, O., Flores, N. & Chu, H. (2011). Extending bilingualism in U.S. secondary education: New variations. International Multilingual Research Journal, 5(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2011.539486 [ Links ]

González Davies, M. (2017). The use of translation in an integrated plurilingual approach to language learning: Teacher strategies and good practices. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 4(2), 124-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/23247797.2017.1407168 [ Links ]

Goodman, B., & Tastanbek, S. (2020). Making the shift from a codeswitching to a translanguaging lens in English language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 55(1), 29-53. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.571 [ Links ]

Guzula, X., McKinney, C., & Tyler, R. (2016). Languaging-for-learning: Legitimising translanguaging and enabling multimodal practices in third spaces. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 34(3), 211-226. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2016.1250360 [ Links ]

Heugh, K. (2015). Epistemologies in multilingual education: Translanguaging and genre-companions in conversation with policy and practice. Language and Education, 29(3), 280-285. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2014.994529 [ Links ]

Hummel, K. M. (2020). Introducing second language acquisition: Perspectives and practices. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2014.994529

Kahiya, A., & Brijlall, D. (2021). What are the strategies for teaching and learning mathematics that can be used effectively in a multilingual classroom? Technology Reports of Kansai University, 63(5),7583-7595. [ Links ]

MacSwan, J. (2017). A Multilingual perspective on translanguaging. American Educational Research Journal, 54, 167-201. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216683935 [ Links ]

Makoni, S., & Pennycook, A. (eds.) (2007). Disinventing and reconstituting languages. In S. Makoni & A. Pennycook (Eds.), Disinventing and reconstituting languages (pp. 141). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853599255

Marshall, S. A., McClain, J. B., & McBride, A. (2023). Reframing translanguaging practices to shift mathematics teachers' language ideologies. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2023.2178683

Otheguy, R., García, O., & Reid, W. (2019). A translanguaging view of the linguistic system of bilinguals. Applied Linguistics Review, 10(4), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2018-0020 [ Links ]

Otsuji, E., & Pennycook, A. (2010). Metrolingualism: Fixity, fluidity and language in flux. International Journal of Multilingualism, 7(3), 240-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710903414331 [ Links ]

Prediger, S., Kuzu, T., Schüler-Meyer, A., & Wagner, J. (2019). One mind, two languages -separate conceptualisations? A case study of students' bilingual modes for dealing with language-related conceptualisations of fractions. Research in Mathematics Education, 21(2), 188-207. https://doi.org/10.1080/14794802.2019.1602561 [ Links ]

Rinneheimo, K., & Suhonen, S. (2022). Mathematical Thinking and Understanding in Learning of Mathematics. International Journal on Math, Science and Technology Education. LUMAT Special Issue, 10(2), 171-189. https://doi.org/10.31129/LUMAT.10.2.1824 [ Links ]

Sahan, K., & Rose, H. (2021). Translanguaging or code-switching? Re-examining the functions of language in EMI classrooms. In B. Di Sabato & B. Hughes (Eds.), Multilingual Perspectives from Europe and Beyond on Language Policy and Practice (pp. 348-356). Abingdon: Routledge.

Sandberg, C. W., Zacharewicz, M., & Gray, T. (2021). Bilingual abstract semantic associative network training (BAbSANT): A Polish-English case study. Journal of Communication Disorders, 93, 106143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2021.106143 [ Links ]

Sibanda, J. (2017). Language at the Grade Three and Four interface: The theory-policy-practice nexus. South African Journal of Education, 37, 1-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n2a1287. [ Links ]

Sibanda, J. (2021). Appreciating the layered and manifest linguistic complexity in mono-multi-lingual STEM classrooms: Challenges and prospects. In A. A. Essien & A. Msimanga (Eds.), Multilingual Education Yearbook 2021 (pp. 19-37). Multilingual Education Yearbook. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72009-4_2

Sibanda, J., & Marongwe, N. (2022). Projecting the Nature of Education for the Future: Implications for Current Practice. Journal of Culture and Values in Education, 5(2), 47-64. https://doi.org/10.46303/jcve.2022.19 [ Links ]

Vallejo, C., & Dooly, M. (2020). Plurilingualism and translanguaging: Emergent approaches and shared concerns. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1600469 [ Links ]

Van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, M., & Drijvers, P. (2014). Realistic Mathematics Education. In S. Lerman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of mathematics education (pp. 521-525). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4978-8_170

van Heuven, W. J. B., Schriefers, H., Dijkstra, T., & Hagoort, T. (2008). Language Conflict in the Bilingual Brain. Cerebral Cortex, 18(11), 2706-716. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhn030 [ Links ]

Wei, L. (2021). Translanguaging as a political stance: Implications for English language education. ELT Journal, 76(2), 172-182. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccab083 [ Links ]

Wei, L., & Lin, A. M. Y. (2019). Translanguaging classroom discourse: Pushing limits, breaking boundaries. Classroom Discourse, 10(3/4), 209-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2019.1635032 [ Links ]

Whorf, B. L. (1956). Language Thought and Reality. Cambridge MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Yao, X. (2021). Metrolingualism in online linguistic landscapes. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.1887197

Zein, S. (2022). Translanguaging and multiliteracies in the English to speakers of other languages (ESOL) classroom. English Teaching, 77(1), 3-24. https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.77.s1.202209.3 [ Links ]

Zwiers, J., Dieckmann, J., Rutherford-Quach, S., Daro, V., Skarin, R., Weiss, S., & Malamut, J. (2017). Principles for the Design of Mathematics Curricula: Promoting Language and Content Development. Retrieved from Stanford University, UL/SCALE website: http://ell.stanford.edu/content/mathematics-resources-additional-resource

Received: 23 July 2023

Accepted: 16 October 2024