Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

On-line version ISSN 2411-9717Print version ISSN 2225-6253

J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. vol.117 n.1 Johannesburg Jan. 2017

https://doi.org/10.17159/2411-9717/2017/v117n1a2

MINING, ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIETY CONFERENCE

Building resilient company-community relationships: a preliminary observation of the thoughts and experiences of community relations practitioners across Africa

N. CoulsonI; P. LedwabaI; A. McCallumII

ICentre for Sustainability in Mining and Industry (CSMI), University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

IISynergy-Global

SYNOPSIS

The University of the Witwatersrand presents an accredited four-course training programme for community relations practitioners (CRPs). Between May 2013 and October 2014 six courses were facilitated for 145 participants, of whom 82% were from sub-Saharan Africa, 62% worked in mining, and 58% worked directly with communities. Thematic analysis of the comments of course participants collected during course exercises found that there were a set of coherent drivers for resilient companycommunity relationships, but that the restrainers to resilient relationships were often context-specific and dominated by politics. CRPs reported facing as many difficulties in the internal company environment as in the external environment. These findings for CRPs in Africa resonate with those worldwide.

Keywords: community-company relationships, community relations practitioners, social licence.

Introduction

Much has changed in how the extractive industry responds to social and community issues. There has been a growing prioritization of community-related issues within the extractive industry globally (Kemp, 2010; Tatar, n.d.). According to Kemp (2010) this can be attributed partly to escalating pressure from local-level stakeholders to push mining companies to take greater responsibility for the social, economic, and environmental impacts of mining. Securing and maintaining the social licence to operate is ranked fourth in terms of the top risks facing the mining and metals industry in 2016, up one place from 2015 (Ernst & Young, 2016).

Conflicts between local communities and large-scale mining companies arise because of the social, environmental, and economic impacts of mining. Worldwide, large-scale mining companies have a poor reputation amongst communities, including those in Africa (Gilberthorpe and Banks, 2012; Kemp and Owen, 2013a; van Wyk, n.d.). For mining companies, conflicts for whatever reason, result in loss of productivity, lost opportunities, lost time, and adverse impacts on reputation (International Council on Mining and Metals, 2015). Conflicts also have a significant financial impact on mining operations (Franks et al., 2014). Davis and Franks (2014), estimated that US$10 000-50 000 is lost each day when a project is delayed during the exploration phase, and about US$20 million per week when in operation. Today these costs could be expected to be higher due to increasing input costs.

Resilient company-community relationships are no longer optional, or something to be disregarded by mining companies. In Africa today, conflict in the mining sector is commonplace, whether between companies and communities, between large-scale mining companies and small-scale miners, or between migrant employees inadequately housed, and local communities. The tragic events in 2012 at the Lonmin Marikana platinum operation in South Africa illustrate that there is still a lot of work to be done to build effective company-community relations in many contexts (Breckenridge, 2014).

In the past decade or so, a plethora of global standards, guidelines, legislation, and initiatives have emerged, resulting in increased rigour in community relations assessment and management. Although an increasing amount is being written about company-community relations, there is very little recorded on the role and experiences of community relation practitioners (CRPs) hired to be the 'face' of a company in the community (Kemp and Owen, 2013a). This paper explores what we can learn about building resilient company-community relationships in Africa, through analysing information captured from course participants during the first two years of the implementation of a training programme designed to strengthen the work practice of CRPs in Africa.

Overview of the CRP training programme

The Centre for Sustainability in Mining and Industry (CSMI) at the University of the Witwatersrand and Synergy-Global came together in 2012 to develop the first African accredited training course for community relations practice in the extractive industry. The Community Relation Practitioner (CRP) Programme was developed to contribute to the profes-sionalization of the discipline of community relations practice by providing an African accredited training opportunity for individuals working as CRPs in the extractive sector. The certificate programme consists of four five-day courses with an assessment for competence required for each course. The courses presented in 2013-2014 are listed in Table I.

The teaching methodology for the CRP Programme is highly participatory and course participants are encouraged to develop as professionals by sharing experiences and reflections on what facilitates and what impedes their work. They are given opportunity to reflect on their experience of the learning process as well. Specifically, participants are asked to capture powerful 'ah-ha' moments that make all the difference for many adult learners. Since 2013, CSMI and Synergy-Global have partnered in facilitating this programme, running up to four courses a year. In the first two years of the programme, participants came from 13 African countries including countries in West, East, and Southern Africa.

Community relations practice in the extractive sector

Community relations can be defined as 'the strategic development of mutually beneficial relationships with targeted communities towards the long-term objective of building reputation and trust (Doorley and Garcia, 2011). Kemp (2010) broadly describes community relations in the extractive sector as a three-stage process that involves working for the company to understand views of local communities; bridging community and company viewpoints to establish a mutual relationship; and facilitating necessary change to enhance social performance. According to Kemp (2010), the scope of work and how community relations work is structured vary according to companies. Some companies regard community relations as part of the communications, public relations, and/or external functions. There are also companies that have embedded community relations work within the corporate social responsibility and/or sustainable development functions. However, many large-scale mining companies have established dedicated community relations departments (Kemp, 2010), and increasingly senior persons are being appointed to lead this work.

The role of community relation practitioners

CRPs play a significant role in unlocking the potential of the industry in terms of enhancing corporate social performance on the ground (Kemp, 2004). While this is somewhat acknowledged, not much is written about the CRPs and how and what they should be doing (Kemp and Owen, 2013a). In fact, very little literature exists on the role and experiences of CRPs as leading agents in building company-community relationships. As stated by Kemp (2004) 'the voice of CRPs seems hidden amongst broader debates about the minerals industry, its social and environmental impacts and progress towards sustainable development. An exception to this is the research led by Professor Kemp from the Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining (CSRM), at the University of Queensland, Australia, which provides the best documented insights into the experiences, concerns, and work of CRPs.

In 2004, CSRM conducted a survey of CRPs working in the mining sector in Australia and New Zealand. The objective of the survey was to develop a profile of CRPs and to gain an understanding of the challenges they face on a daily basis. The survey found that while there was no formal qualification for community relations work, the majority of practitioners were well-educated with considerable industry experience. However, most practitioners did not have prior experience in community relations work, and this skills gap had a direct impact on delivery of work and the challenges faced by practitioners on the ground (Kemp, 2004). This prompted industry stakeholders to develop learning programmes to address this skills gap. In recent years, more formal training opportunities have emerged globally to support CRP practice/profession (Kemp, 2010), the CRP Programme at the University of Witwatersrand being one example. Other institutions that are currently training CRPs across the globe include Catolica University in Chile, the Chamber of Commerce in Papua New Guinea, and CSRM in Australia (Kemp and Owen, 2013a). As previously mentioned, the scope of work of CRPs is rarely defined and hence it is an emerging practice. CRPs find themselves performing a variety of activities, as long as these activities have something to do with communities. According to Kemp (2010), the job performed by CRPs is a mix of consultation and engagement, sponsorships, community programmes, addressing grievances, and public relations. The latter constitutes a large share of the work performed by CRPs.

Challenges experienced by CRPs

Existing evidence suggests that CRPs are faced with a myriad of challenges in their current role. These challenges are both in the external environment as they engage with communities and other stakeholders, as well as internally in their own organization or mining company. The CRPs that took part in the survey conducted by Kemp (2004) listed the following as some of the key challenges: balancing different priorities, understanding the community, limited human and financial resources, poor image of the industry, internal politics, lack of support from management, poor understanding of community relation work by colleagues, and not being perceived as a 'professional'.

There is increasing concern around the impact of internal matters on the performance of CRPs. Kemp (2010) argues that while understanding external factors is important, internal matters also have a direct impact on the performance of CRPs. It is suggested that CRPs face more barriers internally within their organizations than within the communities (Kemp and Bond, 2009; Bourke and Kemp, 2011; Chatham House, 2013; Kemp and Owen, 2013a, 2013b). Some of the concerns raised by CRPs in these studies are that:

► They are excluded from key decision-making processes in their organizations

► They have limited authority in their organizations

► They are a minority profession

► They feel their concerns are given less attention compared to those raised by technical staff

► Community relations is viewed as a burden to the organization

► They struggle to involve other departments in their work

► They do not have a voice in the organization

► Colleagues do not appreciate community relations work

► Internal communication is a challenge

► There is a lack of respect from other parts of the business.

Using data collected through the training of CRPs in Africa, the paper aims to take a preliminary look at the concerns of practitioners in Africa engaged in building resilient company-community relations and the extent to which their concerns and difficulties are shared with practitioners elsewhere.

Methods

Between May 2013 and October 2014 seven courses were facilitated during the first two years of implementation of the CRP Programme (refer to Table I). The data for this paper has been taken from plenary feedback sessions held during the teaching of six courses (Courses 1, 2 and 4) run as part of the CRP Programme. Feedback from group work was captured on flipcharts during training sessions and then transcribed for analysis. During the course sessions, participants were asked at different points to comment on four questions. These were:

1. What are the drivers that enable resilient company-community relations within the extractive industry?

2. What are the challenges that hinder healthy relations?

3. What are the personal challenges faced by CRPs?

4. What are your key learning points from the CRP Programme?

The transcribed flipchart pages were used as qualitative data and analysed for inductive codes. These codes are themes that emerged through the grouping of comments and feedback which when combined provided insight into the collective thinking of the participants. A diagram illustrating the relative weighting and relationship of the inductive codes was then prepared to present the findings for each of the four questions above.

The exception to this process was data compiled as part of 'Course 3: Managing community impacts' held in June 2014. A requirement for this course is the completion of a pre-course survey conducted on Survey Monkey, in which course participants are asked to comment on the progress of their company with respect to community relations practice. Twenty-five course participants completed the survey. The findings of this survey are also referenced periodically in the results to strengthen other findings and observations made through the qualitative data analysis.

A Certificate of Retrospective Acknowledgement Protocol Number N16/07/06 was issued by the University of Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (Non-Medical). It should be emphasized that the findings presented below are the thoughts of course participants as recorded during course sessions. The findings are therefore a preliminary look at the thinking of those working in, or concerned about, community relations practice and should be interrogated further in other empirical studies.

Results

CRP Programme course participants 2013-2014

In total, there were 145 participants/filled teaching places across six courses (refer to Table II). Course participants have not progressed in a linear fashion through the courses and therefore each short course largely reflects a new group of individuals coming together for teaching and learning. However, these figures do reflect some double or triple counting of a few individuals who have attended more than one course. In 2015, only four participants had completed all of the short courses.

Information collected from participants showed that 62% came from the mining sector and 12% from oil and gas. The majority of participants (82%) came from sub-Saharan Africa. Across six courses, 58% of the participants had a job requiring face-to-face interactions with the local community. Other participants had jobs in government, NPOs, were independent consultants, or were in senior management positions. As the records were not always complete, the authors of this paper, who are also the facilitators of these courses, believe that 58% is an underestimate of the number of participants who were working directly with communities. Those working directly with communities came from a range of different company departments, including corporate social responsibility, community development, resettlement, communication, sustainability, public affairs, and community relations. This points to the varied channels through which community relations work is practiced in different settings, and possibly to a lack of standardization and/or the relative infancy of this type of work in the African extractive sector.

What are the drivers of resilient company-community relations?

Ten themes emerged from inductive analysis of the drivers of resilient company-community relations. These themes are shown in Figure 1. Although overall the ten themes emerged to be of similar weighting, three had a slightly stronger emphasis measured by the number of responses that could be attributed to these. These themes are shown in boxes rather than circles in Figure 1 to differentiate them.

Most of the ten themes are self-explanatory. However the theme of 'values' included, for example, important attitudes such as having 'respect', 'integrity', and 'transparency', as well as, 'honesty' and 'trust'. The theme 'mindset' was used to describe a set of responses that described a mutual commitment of the company and the community to be 'responsive', [flexible', and 'ßnd compromise.' The theme 'company readiness' described the general priority placed by the company on community relations and overall management support for this. Although 'effective communication' might have been expected to be a key contributor to good community relations practice, the findings show that it is not a dominant one.

The boxed themes, which carried more weight, were 'values'; 'community and international activism'; and 'policy, legislation, and standards'. Positive value statements are often a feature of company statements and the finding here reinforces the importance of emphasizing these. Local and international activism, such as the existence of pressure groups, human rights watchdogs, and local crisis and other committees, is often not welcomed by the extractive industry sector (Farrell, Hamann, and Mackres, 2012). By embracing local and international activism, CRPs potentially hold a view that is contrary to that of mining management, which often resists organized opposition and local activism. This finding is worthy of further research to examine how organized opposition and activism contribute positively to resilient community relations from the perspective of CRPs. Policy, legislation, and standards create an enabling environment for engagement. Practitioners report that they operate in areas where there is uncertainty about policy, or that policy is inconsistently applied. For example, the pre-course survey found that understanding was fragmented about the company supply chain and its potential for communities. Only 24% of participants reported that company decisions and plans are consistently made based on a detailed understanding of the links between the full supply chain and communities.

What are the challenges that hinder healthy company-community relations?

Nine themes emerged in response to the question 'what are the challenges to resilient relations?' These themes are represented in Figure 2 and were collectively coined 'restrainers'. All the themes are plotted against a shaded backdrop to emphasize the importance of context, and those that featured more strongly in the analysis are shown as boxes. Other themes that emerged less strongly are shown as circles.

Overall, there was less cohesion in the themes that emerged from the analysis of the restrainers than that of the drivers. This suggests that the restrainers, unlike the drivers, do not always have a shared origin but will be more context-specific. Many of the themes are again self-explanatory. However, the theme captured by the term 'fear' included responses from participants such as 'aloofness,' fear of relinquishing control,' 'defensive,' fear of open dialogue,', 'resistant to change,' 'anger and resentment,' as well as, 'bad communication and miscommunication.' All of these sentiments could be attributed to either coming from the community or the company, depending on the context.

Politics impedes resilient company-community relations. Politics is emphasized in Figure 2 to illustrate how much it dominated the other themes. Participant comments about politics included issues related to political interference in community relations work, the politics of mining legacy issues such as poor housing or environmental degradation, the hidden agendas of stakeholders, civil unrest, conflict, and corruption. Politics eclipsed the theme 'education and cultural barriers', which did not feature strongly in the feedback from course participants. In contrast to politics and corruption, CRPs may find that education and cultural barriers to company-community relations easier to manage. Politics and associated corruption clearly hamper the work of CRPs.

The other thematic area that featured strongly in the analysis of the restrainers is that concerned with the allocation of resources to communities. The expectations of companies and communities appears to intensify around the allocation of resources, and this is shown by overlap between the boxes in Figure 2 labelled 'limited resources' and 'assumptions about profits and community expectations'. Participant comments reflected the difficulty faced by CRPs in straddling two worlds: that of the company, dominated by profit margins and commodity prices, and that of the community, struggling to get basic needs met. Despite this vast dichotomy, de facto local struggles to secure resource commitments are affected by global commodity prices. Course participant comments described the 'disconnection between community expectations and company performance; 'the fall of commodity prices', and 'the unrealistic expectations' (both community and company), as well as, the 'the lack of support from management' in trying to find a constructive way forward.

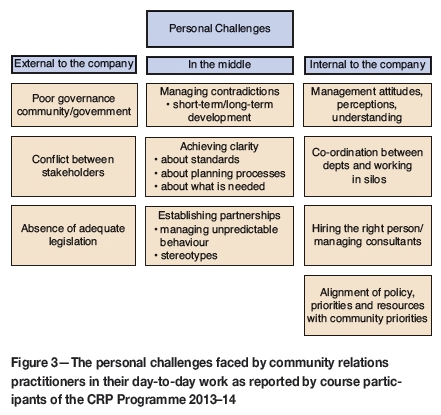

What are the personal challenges faced by CRPs?

The personal challenges are the areas of activity with which CRPs report that they have most difficulty. These are summarized in Figure 3. These challenges are both external of the company and internal to it. In fact, the list of internal challenges was almost as long as that for the external environment. Challenges in the internal company environment were coded into four themes. These are:

► The attitudes, perceptions, and understanding of management

► The poor coordination between departments and history of working in silos

► Employing the right person for the job and/or using the right consultants

► The inadequate alignment of policy priorities and resources inside the company with those of the community they are engaged with.

External to the company environment there were three broad themes that presented the greatest personal challenges to participants. These were:

► Poor governance, both in government and the community, which hampered planning and decision-making

► Conflict between different stakeholders

► The absence of adequate legislation to create an enabling environment for the work of CRPs.

CRPs also faced personal challenges that are reflective of them 'being in the middle'. As one course participant commented,

'Companies want real issues but think that the community relations staff is on the side of the community when they do this.'

Being in the middle is riddled with complexity, and three themes that best described the personal challenges experienced by CRPs were 'managing contradictions', 'achieving clarity', and 'establishing partnerships.' An example provided by participants of 'managing contradictions' is the contradiction of holding the vision required for long-term development goals while satisfying short-term or immediate community or company expectations. The pre-course survey found that dealing with community expectations was one of the highest scoring personal stressors experienced by course participants. Participants reported spending a lot of time and energy 'providing clarity' about relevant standards, planning processes, and the next steps to different role-players . They described the difficulty of managing unpredictable behaviour of stakeholders when setting up partnerships, and breaking down stereotypes that may exist between stakeholder groups.

What are the key learning points from the CRP programme?

Course participants were asked to reflect on what they would take away from the CRP Programme. These key learning points are a reflection of the new insights gained by participants into community relations practice. Six themes emerged in the analysis of the key learning points. These were:

► Look for what is positive

► Be a game-changer

► Listening is the art of communication

► Be in someone else's shoes

► Learning never ends

► Trust.

Being a game-changer was the theme that emerged most strongly. Participants expressed this in different ways from 'thinking outside the box' to 'you don't need to be a/raid of conflict.' Also 'remain flexible because problems will arise and learn to 'accept chaos: The key learning points show that CRPs appear to benefit from strengthening both their interpersonal communication skills and the skills necessary to manage complexity. In the pre-course survey only 32% of respondents reported that their community relations staff have strong competency. Most respondents (44%) preferred adequate competency. Fewer respondents (24%) reported that 'some training is made available to community relations staff, suggesting there is enormous opportunity for appropriate training to upgrade practitioner competency in Africa.

Conclusions

The preliminary findings presented here show that participants enrolled in the CRP Programme report a largely cohesive set of ten positive drivers of resilient companycommunity relations in sub-Saharan Africa. In contrast to this, they report that the restrainers to resilient companycommunity relations are more context-specific. Notably, politics associated with company-community relations is found to be the biggest obstacle to building resilient relationships. CRPs working in Africa need guidance and support to understand the inherently political context in which they work. Training in this area is challenging for practitioners because it addresses ideology and the exercise of power. However, deepening practitioners' understanding of the African development and political context will undoubtedly strengthen those working on the ground.

The findings here reinforce those of Kemp and Bond (2009), Bourke and Kemp (2011), Chatham House (2013), and Kemp and Owen (2013a, 2013b) that CRPs face as many, if not more, challenges inside the company as they do external of it. Course participants reported sitting in the middle mediating contradictions between stakeholders on the inside and those on the outside. Kemp describes the necessity for CRPs to demonstrate 'ambidexterity.'

'A key enabler of successful community relations was the ability of organisations as well as individual practitioners to demonstrate ambidexterity' (Kemp, 2006, p. 1).

One example of this is that practitioners may be expected to operate from a basis of consensus in the internal environment of the company, and manage a more conflictual model of interaction in a community. While individual and organizational tensions are rarely discussed openly in a workplace meeting, grievances, unhappiness, and anger are readily shared in a community. Generally, Kemp's 2006 study found that practitioners sought to find a balance between both environments and tried to balance both company and community perspectives, although it did appear that perhaps the company perspective had priority. This ambidexterity is an important practical consideration for those building the capacity of professionals for community relations practice.

Overall, it appears that the preliminary analysis of the comments of course participants registered on the CRP Programme resonates with other findings about CRPs worldwide. This points to the importance of supporting a globally recognized set of professional competencies for CRPs. However, the challenges faced by CRPs reflect their immediate context and CRPs in Africa need to be prepared for political complexity. Training for CRPs can be conducted across the globe provided there are opportunities to share experience and to engage with specific contexts. Importantly, a CRP trained and skilled in Africa can contribute to a global mining industry.

References

Breckenridge, K. 2014. Marikana and the limits of biopolitics: themes in the recent scholarship of South African mining. Africa, vol. 84, no. 1. pp. 151-161. [ Links ]

Bourke, P. and Kemp, D. 2011. The role of community relations practitioners as change agents in the minerals industry. Proceedings of the First International Seminar on Social Responsibility in Mining, Santiago, Chile, 19-21 October 2011. https://wwww.csrm.uq.edu.au/publications/the-role-of-community-relations-practitioners-as-change-agents-in-the-minerals-industry [ Links ]

Chatham House. 2013. Revisiting approaches to community relations in extractive industries: Old problems, new avenues? Energy, Environment and Resources Summary, vol. 4, June 2013. [ Links ]

Davis, R. and Frank, D.M. 2014. Cost of company-community conflict in the extractive sector. CSR Initiative at the Harvard Kennedy School. https://www.hks.harvard.edu/m-rcbg/CSRI/research/Costs%20of%20Conflict_Davis%20%20Franks.pdf [ Links ]

Doorley, J. and Garcia, H.F. 2011. Reputation Management: The Key to Successful Public Relations and Corporate Communication. Routledge, New York, London. [ Links ]

Ernst & Young. 2016. Business risks facing mining and metals 2016-2017. http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/EY-business-risks-in-mining-and-metals-2016-2017/$FILE/EY-business-risks-in-mining-and-metals-2016-2017.pdf [ Links ]

Farrell, L.A., Hamann, R., and Mackres, E. 2012. A clash of cultures (and lawyers): Anglo Platinum and mine-affected communities in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Resources Policy, vol. 37, no. 2. pp. 194-204. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2011.05.003 [ Links ]

Franks, D.M., Davis, R., Bebbington, A.J., Ali, S.H., Kemp, D., and Scurrah, M. 2014. Conflict translates environmental and social risk into business costs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 111, no. 21. pp. 7576-7581. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1405135111 [ Links ]

Gilberthorpe, E. and Banks, G. 2012. Development on whose terms?: CSR discourse and social realities in Papua New Guinea's extractive industries sector. Resources Policy, vol. 37, no. 2. pp. 185-193. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2011.09.005 [ Links ]

Kemp, D. 2010. Community relations in the global mining industry: exploring the internal dimensions of externally orientated work. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/csr.195/epdf [ Links ]

Kemp, D. 2006. Between a rock and a hard place: community relations work in the minerals industry. Paper no. 5. Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining Research. http://info.worldbank.org/etools/docs/library/238485/kemp.pdf [ Links ]

Kemp, D. 2004. The emerging field of community relations: profiling the practitioner perspective. Proceedings of the Inaugural Minerals Council of Australia Global Sustainable Development Conference, Melbourne, November 2004. https://www.csrm.uq.edu.au/publications/the-emerging-field-of-community-relations-profiling-the-practitioner-perspective [ Links ]

Kemp, D. and Bond, C.J. 2009. Mining industry perspectives on handling community grievances. Summary and analysis of industry interviews. Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, university of Queensland and Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative, Harvard Kennedy School. http://www.csrm.uq.edu.au/docs/Mining%20industry%20perspectives%20on%20handl ing%20community%20grievances.pdf [ Links ]

Kemp, D. and Owen, J. 2013a. Mining and community relations practitioner roundtable: report from South East Asia. http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:331448 [ Links ]

Kemp, D. and Owen, J.R. 2013b. Community relations and mining: Core to business but not 'core business.' Resources Policy, vol. 38, no. 4. pp. 523-531. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2013.08.003 [ Links ]

TATAR, I. Not dated. Community relations and the extractive sector. CIITO Strategies Inc. http://ciito.ca/wp-content/uploads/Community-Relations-and-the-Extractive-Sector-CIITO.pdf [ Links ]

Van Wyk, D. Not dated. The policy gap a review of the corporate social responsibility programmes of the platinum mining industry in the North West Province. Bench Marks Foundation. http://www.bench-marks.org.za/research/Rustenburg%20platinum%20research%20summay.pdf [ Links ]

This paper was first presented at the Mining, Environment and Society Conference ´Beyond sustainability - Building resilience´, 12–13 May 2015, Mintek, Randburg, South Africa.