Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences

On-line version ISSN 2222-3436Print version ISSN 1015-8812

S. Afr. j. econ. manag. sci. vol.28 n.1 Pretoria 2025

https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v28i1.6480

EDITORIAL

Can you spell 'academic' without 'AI'?

Yudhvir Seetharam

School of Economics and Finance, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ChatGPT has become a dreaded popularised word in academic circles. Who would have thought that an artificial intelligence (AI) programme can drum up such strong emotion from both proponents and opponents! Briefly, ChatGPT is a Large Language Model (LLM) that can respond in a conversational manner to questions asked by the user (OpenAI 2023). Just as the atom bomb once evoked fear, so too does this chatbot - along with broader Generative AI (GenAI) or the newly coined buzzword around Silicon Valley, Agentic AI - elicit strong reactions from academics.

It's worth highlighting that AI is not actual intelligence. Our thought processes and decision-making capabilities are still sufficiently complex to distinguish us from machines (well, this applies for most of us). There are, however, some tasks that we must admit that AI can do better, quicker and more efficiently - whether that is driving, performing complex calculations without pen and paper or being the best English professor in the world, over the history of the world.

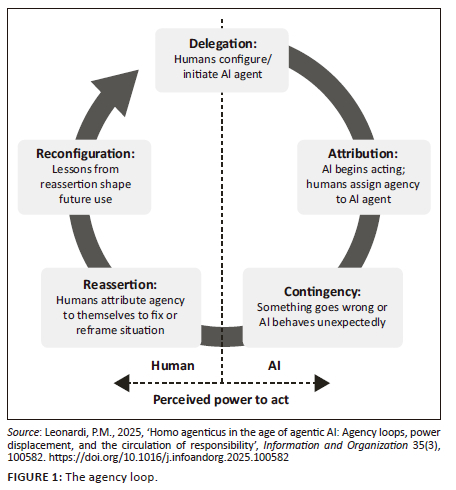

Figure 1 shows the agency loop that Leonardi (2025) defines as the amount of power (autonomy or liberty) that humans assign to AI for a given task. In doing so, we inherently acknowledge that the machine may produce inaccurate results and/or make incorrect decisions. However, the mere act of delegating frees our intellectual capacity for other intellectual endeavours. We did not initially, inter alia, embrace the telephone over the telegram; the cell phone over the telephone; or the calculator over the abacus. But as we saw the value afforded from such tools, it became a self-fulfilling prophecy for the said tools to become more accurate and meaningful in our lives.

While AI terms can become complicated quickly, AI simply relates to the ability of a machine to learn from the past to generate a more accurate outcome. This has been popularised by machine learning algorithms, which all involve some form of learning (supervised or unsupervised) to lower the error between actual and predicted values. Generative AI produces a specific answer based on a specific prompt. Generative AI methods are based on LLMs that are trained on a database (a dictionary or a corpus) and predict what is the most likely response to a prompt by the user. Simply, GenAI creates content - whether text, imagery, code or even music - based on the knowledge it was trained on. The most popular example of GenAI is ChatGPT.

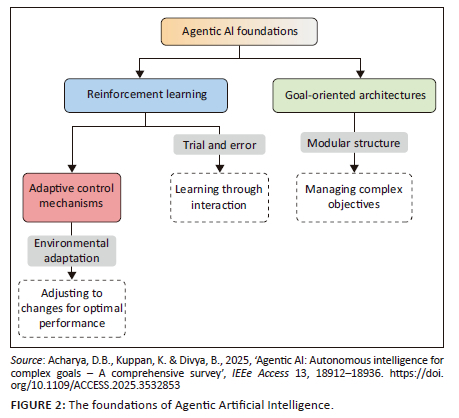

In contrast to GenAI, Agentic AI (Figure 2) can make decisions based on content (whether produced by man or machine), thereby providing more flexibility to automate tasks. Agentic AI can rely on GenAI output. An example here would be a virtual assistant, Microsoft Copilot (which can read and respond to mails on your behalf) or autonomous vehicles. Agentic AI, therefore, learns, whether through trial and error or through adapting to responses given by the user, to produce more accurate output (here defined as more accurate decisions).

The call for academia to embrace artificial intelligence

In a world where employees are pressured, including those at higher education institutions, to be more productive, the allure of AI to facilitate being smarter and more effective in fulfilling one's responsibilities is high. A typical academic is required to teach, to supervise, to produce research and to contribute to the broader (academic) community through a variety of initiatives. While these responsibilities have not changed over many decades, higher student numbers, higher demands for tenure or promotion and higher exogenous factors from both government and society often imply that the academic of yesteryear is ill-equipped to manage the current (volatile, uncertain, ambiguous and complex) environment. The high uptake of GenAI is a testament to these matters being universal across jurisdictions, industries and work levels.

What is strange is that the GenAI adoption rate of academics, especially in commerce fields, is lagging other industries instead of being a forerunner. Perhaps this is because of the risk-averse nature of academics to adapting to change. This has been seen historically with the introduction of calculators in the classroom, the rise of the internet and the adoption of online learning platforms, which were all met with initial scepticism before becoming integral to educational practice. These transitions illustrate academia's capacity to adapt while preserving its core values. I will now briefly discuss two important responsibilities (teaching and research).

Teaching

The use of AI in the classroom was accelerated by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (Amankwah-Amoah et al. 2021). Lectures have been supplemented with videos, discussion/blog posts and virtual labs, thereby creating a hybrid learning environment. The traditional lecture structure of hearing the professor in a monologue has (albeit) slowly been replaced by dialogue, forcing students to engage in critical thinking and higher order reasoning. This shift ensures that we do not produce widgets but working-class citizens. Artificial intelligence, in its simplest form, can be used in classroom teaching to enable students to visualise complex concepts that are difficult to convey using traditional 2D text and graphical formats. This is analogous to why movies introduced surround sound. The use of AI in this manner typically does not raise any eyebrows. Yet, as you will read next, I anticipate some eyebrows being raised when AI is integrated more deeply within classroom environments.

Professors are accustomed to having teaching assistants - often junior staff or those pursuing postgraduate degrees - who can answer questions from students, conduct tutorials and be a 'backup' to the lecturer. Is it that far-fetched to believe that a bot can set tutorials or interact with all students simultaneously? If we are used to answering a bot on a website or in a banking app, then why not in a lecture hall? This naturally becomes a double-edged sword. The more that we automate or digitalise, the less emphasis is placed on human interactions and the various benefits thereof. There is sufficient evidence that in-person interactions with students enhance their understanding of concepts and development of competencies. As such, while a bot may be able to substitute the human assistant, one must question what else is missing to ensure such a successful outcome. In other words, do we sufficiently understand the nuances in creating efficiency via digitalisation yet potentially lowering effectiveness via less human interaction?

Instead, our singular focus has been on the perceived danger and risk in how students use these tools to plagiarise material from a variety of other sources. While this is sometimes true, it is no different from 'Google' that the same students have had access to for decades. Yes, plagiarism does not produce ethical and technically sound students; however, we must not forget that our assessment standards should be challenged so that we elevate the amount of critical thinking/discourse and limit the amount of rote learning. Indeed, it is called machine learning - any rote learning task is meant to be performed better by a machine than by people!

Plagiarism undermines the development of ethical and competent graduates and has the profound consequence of stealing students' ability to learn and develop critical thinking skills. Ethical considerations surrounding the use of AI in academia are multifaceted. While plagiarism and misrepresentation of AI-generated content are valid concerns, the broader ethical discourse must also include transparency, accountability and authorship. Institutions are establishing (clear) guidelines on the use of AI tools in research and teaching, ensuring that contributions made by AI are acknowledged and that human oversight remains paramount. Moreover, the ethical training of students and faculty should evolve to include digital literacy and responsible AI usage, preparing them to navigate the complexities of academic integrity in a technologically advanced environment. This, indeed, is how many large corporations are upskilling their employees. If universities are to remain relevant in a world where micro-learning, micro-accreditation and 'Udemy'-like platforms are seen as competitors, we must proactively address these challenges.

In South Africa, some higher education institutions have pioneered research hubs, programmes and initiatives that focus on digital transformation. However, broader infrastructure challenges, policy gaps and systemic support are still prevalent hurdles in the adoption of AI.

Research

Here I focus on research within my field of finance, lest I garner criticism from the varied readership of this journal. Our research within economic and management sciences is often more empirical than theoretical - it is seldom that we see a published article about a newly coined theorem. Instead, much of our work is based on observation, which is then evaluated against existing theory. The key to publishing an article in a high-quality journal rests on the strength of the argument, identifying the gap in the literature, the strength of the data and methodology and the insights from the results which, in most cases, either support or oppose the prevailing theory. This 'research lifecycle' has been around significantly longer than any AI phrase that was coined in the 1950s. Similar to our risk aversion in adopting new technologies for teaching, academics have also been cautious of how to use AI in the research lifecycle, and yet, as I will illustrate, some have relied on the human version of AI in our research for decades.

Against other responsibilities for the academic, time is often not on our side. Enter the research assistant - an often-temporary employee of the university who is meant to assist in gathering and synthesising literature, gathering and cleaning data, conducting analyses and assisting in the write-up of the article. As I list all these responsibilities, it should become clear to the reader that some (if not all) can be subsumed by AI. After all, researchers need to verify the accuracy of data collected whether by human or AI assistants. Why is it, then, that academia has cast such a fearful shadow over the use of AI in research? Because a few (or many) have blatantly passed off the assistant's work as their own and/or have not assessed their assistant's work for clarity. Again, this is not new! How many published articles have not acknowledged the human research assistant either as a co-author or in a footnote?

A similar argument can be made for activities that are classified as 'academic citizenship'. Whether we are an examiner for a student or a course or a reviewer for a journal, there, again, are means to make our job more effective. It is therefore not about whether we use AI in these tasks, but rather how the quality of the output deteriorates if we decide to use means that can potentially be detrimental to our field. The common denominator across all these tasks is to ensure quality control - are we as a higher education sector producing graduates who are capable of not just meeting but exceeding expectations in the field? If I, as a journal reviewer, use AI in writing my review, am I ensuring sufficient quality control for my field by allowing an article to be published, which has blatant errors in it? If I am an examiner who uses AI to assess the work of the student, am I allowing a student to qualify when they have not shown sufficient mastery of the subject matter? Again, you can replace AI with 'assistant' in the above examples and reach the same conclusion. Also note that these LLMs are trained on existing data, which, by definition, are not favourable to any data point that 'challenges the norm' - so if the content of the journal article or student research directly challenges existing work, chances are that the machine will have an unfavourable review (think of it as 'reversion to the mean'). Quality control, therefore, should remain the responsibility of the academic, instead of being delegated to any assistant (virtual or otherwise). What remains to be solved for is the academic's ethical standards and an acute humility when the awareness of when such standards of their own are lower than that found in an assistant.

To artificial intelligence or not to artificial intelligence?

You will never (or rather rarely) see an academic using an abacus today. This tells me that somehow, we overcame our risk aversion to technology and embraced it - whether it is a simple abacus, a 'modern' calculator, an Excel spreadsheet, a programming language, a Spellcheck function in Microsoft Word or a human being (who we call an assistant or a Copy Editor). These technological advancements have come with the commensurate guidelines to ensure that the work we produce meets academic standards. Generative AI is simply another tool, and the requisite standards must be in place to ensure its fair and ethical use. There are some questions that you can definitively answer, others that you cannot, and a third set that either have not yet been asked and/or do not have any answer. It is up to us as academics to use these tools for the first, and arguably the second, while we personally spend our time on the third - our aspiration as academics should be in creating new knowledge at least once in our career, while we test existing knowledge as part of our daily bread.

Looking ahead, the integration of AI in academia is poised to reshape the landscape of higher education. Agentic AI, with its capacity for autonomous decision-making, offers opportunities for personalised learning, automated administrative tasks and enhanced research capabilities. However, this evolution must be guided by thoughtful policymaking and inclusive dialogue among stakeholders. Academia must proactively adapt curricula, research methodologies and institutional frameworks to harness the benefits of AI while safeguarding the core values of scholarship, critical inquiry and human creativity. We are already lagging behind the GenAI curve - this is a call to ensure we do not just catch up to the wave but overtake it such that once Agentic AI (soon) proliferates certain decision-making functions within higher education institutions, we are not found lacking.

Note: This Editorial is based on my own experience and reading of the literature, both academic and professional. It has been edited by Microsoft Copilot to ensure that it conforms to the standards of an Editorial in any finance-related academic journal. Indeed, this is not the first time that a digital worker has helped edit my work in 'proper English' because of a reviewer's criticism that their English is of a higher standard than mine. Any remaining faults remain my own.

References

Acharya, D.B., Kuppan, K. & Divya, B., 2025, 'Agentic AI: Autonomous intelligence for complex goals - A comprehensive survey', IEEe Access 13, 18912-18936. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3532853 [ Links ]

Amankwah-Amoah, J., Khan, Z., Wood, G. & Knight, G., 2021, 'COVID-19 and digitalization: The great acceleration', Journal of Business Research 136, 602-611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.08.011 [ Links ]

Leonardi, P.M., 2025, 'Homo agenticus in the age of agentic AI: Agency loops, power displacement, and the circulation of responsibility', Information and Organization 35(3), 100582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2025.100582 [ Links ]

OpenAI, 2023, ChatGPT: Optimizing language models for dialogue, viewed 02 August 2025, from https://openai.com/chatgpt. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Yudhvir Seetharam

yudhvir.seetharam@wits.ac.za